Bülten-Adenstedt mine

| Bülten-Adenstedt mine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| General information about the mine | |||

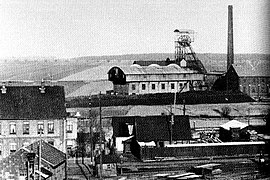

| The Kaiser Wilhelm Shaft around 1908 | |||

| Mining technology | Opencast mining and chamber mining | ||

| Funding / year | up to 1.1 million t | ||

| Funding / total | 60 million tons of iron ore | ||

| Rare minerals | Groutite , Ramsdellite , Rhodochrosite , Kutnohorite | ||

| Information about the mining company | |||

| Operating company | Ilseder Hut | ||

| Employees | up to 1258 (1957) | ||

| Start of operation | 1860 | ||

| End of operation | March 30, 1976 | ||

| Funded raw materials | |||

| Degradation of | Brown iron stone | ||

| Greatest depth | 235 m | ||

| Geographical location | |||

| Coordinates | 52 ° 16 '45 " N , 10 ° 12' 33" E | ||

|

|||

| Location | Bülten | ||

| local community | Ilsede | ||

| District ( NUTS3 ) | Torment | ||

| country | State of Lower Saxony | ||

| Country | Germany | ||

| District | Peine-Salzgitter area | ||

The Bülten-Adenstedt mine is a former iron ore mine in the Peine district in Lower Saxony . The opencast mines and pits were located in an area between the villages of Adenstedt , Groß Bülten , Bülten and Ölsburg .

The Bültener ores formed the raw material basis of the nearby Ilseder Hütte for over a hundred years . This produced the pig iron for the world-famous Peiner porters .

geology

The origins of the Bülten ore deposit

When Bültener ore deposit is a marine sedimentary Trümmererz deposit- .

In the Upper Cretaceous at the time of the Santonium (older name: Oberemscher ), the coastline of a sea was in the area of the Peiner ore deposits. On the coast of the clay layers were Gault at (upper Cretaceous) in which Toneisenstein - geodes were embedded. The clay iron stones were created by the precipitation of iron dissolved in the water in the immediate vicinity of animal carcasses, which were embedded in the still largely unconsolidated, water-saturated clay sediment and the decomposition of which had created a chemical environment favorable for the precipitation. The geodes were spherical or loaf-shaped with a diameter of up to one meter. The sea surf eroded the easily weatherable clay stones in the Santon and the heavy clay iron soil remained on the beaches. The surf shattered the geodes and the fragments were ground again (so-called reconditioning ) and at the same time the clay iron stone weathered from the outside to form limonite . The limonite rind partially flaked off like shards. By the rise of neighboring salt dome Ölsburg or rather by taking away the salt from around the salt dome emerged in the area of former coastal waters edge lowering, in which the Limonitgerölle and -trümmer that were carried by strong currents into the deeper water, in bauwürdiger thickness accumulate could.

Geographical location and extent

The Bülten ore deposit begins on the northern edge of Adenstedt and stretches from west-south-west to east-south-east over a length of about six kilometers. It is traversed by several disturbances , e.g. B. Bülten main disorder, Ölsburg disorder . With an average building width of 800 meters, the camp falls 6 to 22 gon to the northwest. In the south-east the ores stood for days over almost the entire length to Ölsburg ( outcrop ). At Bülten, however, they were at a depth of 250 meters. The hanging wall above the 4 to 28 meter thick ore deposit consists of layers of marl and diluvial gravels and sands. The lying was formed from layers of clay (Gault) from the Lower Cretaceous . After an extensive clouding zone in front of the Mittelland Canal, ores were again in 400 to 700 m, which were extracted from the Peine I / II mine in Peine-Telgte .

mineralogy

The Bülten ores consisted of various ore rubble and debris that were embedded in a chalky to marly base. The mineralogists classified the irregular ore in

- Ore shell pebbles with a hard shell and an often clay-filled cavity, they were the most common,

- Ore net pebbles without voids made from a limonite matrix,

- Uniform brown iron pebbles of moderate strength,

- Shelly brown iron balls that were built up like an onion and

- Phosphorites , which consisted essentially of apatite .

The average composition was: 26.5 to 28% Fe , 2.6 to 3.3% Mn , 0.9 to 1% P , 20 to 25% CaO and 5 to 7% SiO 2 .

The ore pebbles and the dead rock immediately surrounding them had different discolorations depending on their composition. Then the miners differentiated the ore into red-colored , red-brown , white-brown and green-colored ore.

The cavities of the ores also contained rare minerals due to penetrated solutions. From there u. a. known:

- Groutite , a black manganese oxide chemically identical to manganite , which occurred in tabular aggregates in the drusen of the ore shell pebbles - red-brown ore,

- Ramsdellite , a black, shiny metallic manganese oxide,

- Rhodochrosite , a manganese carbonate that forms from white to pink to brownish-red crystals and

- Kutnohorite , white to light yellow / light pink. A calcium-manganese double carbonate “related” to dolomite .

History and technology

Predecessor mining

On the basis of slag finds, smelting of the near-surface Bülten ores can be proven as early as the 3rd century . A second period lasted from the 10th to the 14th centuries . Written documents about mining in the Bülten-Adenstedt area are only available for the 19th century . In a report by the geologist Strombeck from 1858 it is said that there is an old opencast mine near Groß-Bülten , which " ... of course not for smelting, but because there is a lack of better material in the area, for making paths and the like. is won ". Investigations commissioned by Hildesheim Senator Roemer in 1848 even confirm that the iron content was too low for the ironworking processes of the time.

Carl Hostmann's visions

The Celle banker Carl Hostmann and his partner Fritz Hurtzig have been investigating a hard coal deposit on the Oberg near Ilsede not far from the Bülten ore deposit since 1853 . In 1856 they acquired concessions to visit the iron ore deposit after they were personally able to win Justus von Liebig as an appraiser. Hostmann and Hurtzig recognized the possibility of obtaining ore inexpensively in open-cast mining and processing it directly into iron in a nearby iron and steel works with the help of the coal that occurs in the immediate vicinity. In 1856, for example, the Peine mining and smelting company was founded. At the time, Hostmann criticized Germany's dependence on foreign raw material imports and urged potential investors to promote their own raw material base. In the Peine area he saw an iron ore deposit which had not yet been found in Germany of this size and which was supposed to deliver a million cents of good iron annually for centuries . He planned a mining center in the Peine area, which in his opinion had a perfect connection through the Hanover - Braunschweig railway . The pig iron produced was to be processed into industrial products in connected steel and rolling mills , foundries and machine factories. Because of the short transport routes, Hostmann reckons with low prime costs. Such a mining center was to be built a little later in Germany in the Ruhr area . The plant in Peine was not built initially. The supposed coal seams turned out to be unsuitable for construction, investors stayed away or felt deceived by his founding prospect . Hostmann had to file for bankruptcy and shortly afterwards committed suicide on January 21, 1858.

The history of the Bülten mining industry from 1860 to 1933

The establishment of the Ilseder Hütte and the start of mining

Carl Hostmann's son-in-law Carl Haarmann acquired the mining fields from the bankruptcy estate and on September 6, 1858, together with Hostmann's former partner Hurtzig, founded the Ilseder Hütte company . After successful agreements with the property owners, the first open-cast mine in Bülten I, West , was opened in February 1860 . The dismantling and transport was initially carried out by a contractor.

The first blast furnace in Groß Ilsede was blown in 1860, the second in 1861. Also in 1861 a horse-drawn tram was built to transport the ores.

As early as 1862 there was a sales crisis for the pig iron produced. The utilization of the two blast furnaces had to be reduced to a third of their capacity and in 1863 the end was threatened. The reason was the high phosphorus content of the iron, which made it difficult to further process it. The management of the hut was able to recruit entrepreneur and businessman Gerhard Lucas Meyer for the board of directors. It was thanks to his skill that just one year later ... Ilseder pig iron was (was) the cheapest to produce in Germany at the time . Comparatively low costs and high performance should remain the recipe for success of the Bülten mining industry for more than a hundred years.

The first heyday of mining in Bülten

After the third blast furnace of the Ilseder Hütte was put into operation in 1865, the expansion of the mine in Groß-Bülten also made rapid progress. Engelhard Bingmann took over the management of the mining department in 1866 and held this position until his death on November 3, 1907.

While 13,300 tons of ore were mined in 1867, a year later it was already 156,300 tons.

As the first slot in 1869 was Carl slot m to 27.5 sunk . It was used exclusively for drainage . With the exception of the ores accumulated when driving the swamp and the connecting routes to the open pit, no underground mining has been carried out as planned.

After the ores that were immediately exposed had been mined, the overburden layer had to be removed with a shovel for digestion . At first it was only a few meters, but as the mining progressed, the surface layer increased due to the collapse of the camp. Because of the great thickness of the deposit, the ores were mined on several terraces one above the other, so-called stopes . The stopes were 2 to 3 m high and 4 m wide. Blasting with black powder was used .

The loaded trams reached the level of the natural ground via so-called brake mountains . Initially this work was done by horses, but as early as 1869 there was reports of the first hoisting machine . The demineralised open pit trench was in accordance with the face advance again to the other side of the overburden , rubble and waste turned over.

The second open-cast mine was the Bülten I, east 1 open-cast mine . This was separated from the west opencast mine by the Bülten main fault.

With the completion of the 25.5 m deep Gerhard shaft (old) in March 1877, the system of extraction changed. The mined ore has now been incident routes in ore underground to fill location of production well decelerated . The upward moving empty train served as a counterweight via a pulley. The wagons were lifted for days in the Gerhard shaft .

In 1881 there were already 6300 m underground stretches, although mining was still carried out in open-cast mining. The Hermann Shaft with a depth of 22.8 m was built as a further extraction shaft in 1883 . Further opencast mines existed from 1890 with the opencast mine Bülten I, Osten 2 , also called barracks pit and with the opencast mine Adenstedt . The latter was known colloquially as Knippelkuhle , which comes from an old abandoned open-cast mine in which Gnippeln = iron stones were found. At the edge of the Adenstedt opencast mine, the Engelhard shaft (depth 30.2 m) was sunk.

In order to enable work on winter evenings, electrical lighting was introduced in the opencast mines as early as February 1896. This was a peculiarity because at that time only large cities had an electrical power supply. Peine himself only received one in 1916.

In 1897, annual production exceeded 400,000 tons .

The Kaiser Wilhelm shaft , sunk from 1899 to 1900 , became the first real underground construction shaft of the Bülten-Adenstedt mine. On the 60 m floor of the 67.4 m deep shaft, the installation of the ore storage underground began. From an overburden of 30 m, the opencast mine was no longer considered economical at the turn of the century. The shaft system initially received a steam hoisting machine, which was converted to an electric drive in 1909.

The old Gerhard shaft fell victim to the advancement of the open pit in 1907, the Engelhard shaft in 1910 and the Hermann shaft in 1917. The new shaft was built to replace it in 1908 . In the same year, the frog lamps previously used as lights by miners were replaced by carbide lamps .

Steam shovel excavators have made it easier to remove the increasingly thick layer of overburden since 1909 .

The second underground construction shaft was the 130 m deep Gerhardschacht in 1914 . The 120 m level and the eastern 60 m level were connected to this. The Gerhard shaft was a double shaft and at that time already had a vessel feed .

As downhole mining method was pillar method applied in Bülten also Inclined Scheibenbau called: Because of the thickness was the ore successively in three superimposed discs removed. The chambers created for this purpose were around 6 m high and wide and 80 m long. First the lowest, then the overlying discs were won. The extraction took place through drilling and shooting work . The ore was losgeschossene with scabies and trough loaded into trams and people with power to the main routes promoted . Electric mine locomotives were used to transport them to the filling points of the shafts .

To protect the surface, it was necessary to work with an offset due to the low cover and the proximity to inhabited areas . For this purpose, sand extracted from underground pits was washed into the removed chambers. One of these sand pits later became the Groß Bülten-Adenstedt landing pond , now a nature reserve and local recreation area.

The importance of the Bülten-Adenstedt mine in the First World War

During the First World War , the German Reich was cut off from its foreign raw material sources. Iron ore was of great importance for the production of goods essential to the war effort. The Bültener ores also contained larger amounts of manganese , which was important for the production of hard manganese steels (compare expansion of the Dr. Geier mine in Waldalgesheim ). These high-strength steels were used in the manufacture of armor for warships, gun turrets and the like, as well as for railroad tracks. As part of the Hindenburg program , funding in Bülten-Adenstedt was therefore expanded. As a result, the originally orderly expansion of the mine was deviated from and particularly iron-rich parts were preferentially taken into account → overexploitation . The mined ores had to be delivered to the smelters in the Ruhr area by imperial decree .

In the area of the Knippelkuhle opencast mine near Adenstedt, there were particularly manganese-rich parts that continued to below the location of Adenstedt. Because of the high demand for manganese, this deposit was taken down. For this purpose, the church, including the cemetery and a total of 56 farm buildings and farm buildings, had to be demolished. The Ilseder Hütte undertook to rebuild the church elsewhere and had to compensate the property owners. Some roads were also relocated. In peacetime this project would never have paid off because of the costs.

Despite the use of prisoners of war, the required services were not achieved due to a lack of personnel.

The Bülten mining industry during the Weimar Republic and the Great Depression

After the war, the situation returned to normal. The mining moved into greater depths in favor of civil engineering . Therefore, the underground route network has been expanded considerably. In order to increase the extraction rate, scrapers were introduced in both surface and underground mining at the end of the 1920s . These coated with scrapers, which from a winch has been moved, the losgeschossene debris into a loading device for the trolley. This made loading work much easier. The work done per man and shift increased from 2.5 to 5.4 tons. In 1928, tests were carried out underground with the so-called Butler loading shovel from the USA. This excavator-like device, known by the miners as the Eisener Bergmann , was wedged onto rails and loaded directly onto a trolley or a conveyor belt . The Bülten ore ultimately turned out to be too hard for the machine.

During the global economic crisis from 1930 to 1933 the demand on the world market for iron and steel and thus also for the ore from the Bülten-Adenstedt mine fell sharply. In 1930 this was only done one shift a day. In 1932 the mine was completely idle for a total of 5 months. In the remaining months, they only worked half a week. This resulted in an economic emergency for the miners, as there was a considerable loss of income.

The history of the Bülten mining industry from 1934 to 1976

The expansion during the four-year plan

As part of the four-year plan , the National Socialist rulers envisaged making Germany independent of foreign raw material imports. In order to revive the armaments industry, an increase in iron and steel production was necessary at the same time. Support programs for iron ore mining have been set up accordingly. As a result, as early as 1934, there were no more party shifts in the Bülten-Adenstedt mine. Since the open-cast mines in Bülten and Adenstedt had largely been removed, a new open-cast mine was set up in Ölsburg in 1938. Furthermore, all underground ores should be prepared for mining as quickly as possible. For this purpose, a new shaft, the Emilieschacht , was also sunk in 1938 . The 50 m thick sand layers were drilled using the freeze shaft method . The final depth was 235 m. The 220 m level was set up as the new main lift level.

Shortly before and during the Second World War , new maximum funding figures were reached. With the collapse at the end of the war, mining came to a complete standstill. In November 1945 operations could be resumed. However, it took a few years for the situation to stabilize due to a lack of materials and staff.

In 1949, a conveyor ramp was driven from the base of the Ölsburg opencast mine to the 90 m level. This means that in the future all larger machines could be brought into the pit from above without having to dismantle them beforehand. That year 610,800 tons were extracted and 1000 miners were created.

The largest production in the history of the Bülten mining industry was achieved in 1957 with a little more than 1.1 million tons with a workforce of 1258.

Rationalization and the struggle for survival during the decline of German iron ore mining

At the end of 1961, the most important steel companies in the Ruhr area decided not to purchase domestic iron ores in the future. At this point in time, a ton of German ore with about 30% iron content cost around 100 German marks , a ton from Sweden including transport cost 51 German marks with 60% iron. While the Bülten-Adenstedt mine was not directly affected by this, as it supplied its ores to the blast furnace plant in Groß Ilsede, it came under great pressure from the inexpensive imports. In addition, the better ore lots had already been mined in the two world wars. Survival was only possible through an increase in productivity while reducing costs.

The following rationalization measures were implemented in the following years:

- Funding and ropeway travel took place exclusively via the Emilieschacht. The Kaiser Wilhelm shaft was shut down on October 31, 1961. In order to also be able to shed the Gerhardschacht, a chairlift was built underground in 1964 from the 220 m bottom of the Emilieschacht to the 140 m bottom of the Gerhardschacht. The miners could use this 530 m long cable car to travel to the Gerhardschacht area.

- In the years 1964 to 1965, trackless, electro- and diesel-hydraulic drilling jigs were purchased. This allowed the blast holes to be drilled up to 20 times faster. From then on , the shots were loaded with loose explosives using compressed air from a special shooting vehicle.

- Large areas were set up and converted to trackless mining. So-called transloaders have been used over shorter distances since 1967 . These vehicles were constructive a mix between shovels and car Schütter ( Dumper ) and could easily accommodate their cargo of 8 tons. An original transloader from Bülten is preserved in the German Mining Museum in Bochum . Unimogs had already been in use over longer distances (up to 2.6 km) since 1965 . These were loaded by swivel loaders from Eberhard .

The pit could be accessed by vehicles from above ground through the ramp in the Ölsberg opencast mine.

As a result, the output could be increased from 8 tons per man and shift (t / MS) in 1963 to 22 tons by 1970. This exhausted the conventional possibilities.

Since 1965, mining machines from American hard coal mining (so-called continuous miners ) have been used successfully in the clayey ore of the neighboring Lengede-Broistedt mine . The Bülten ore was too hard for the rotating cutting chains of this type. Therefore, tests were carried out with an Austrian roadheader for tunnel construction . After good results, Ilseder Hütte acquired several machines from voestalpine and Westfalia Lünen for cutting mining. The largest type used could solve up to 100 tons of ore per hour. Ultimately, this meant that tusk outputs of 27.2 t / MS were achieved by 1976.

In the 1970s, Stahlwerke Peine-Salzgitter AG decided to withdraw from ore mining. The predecessor of today's Salzgitter AG took over Ilseder Hütte and its operations.

On March 30, 1976, the last wagon was transported to the hanging bank of the Emilieschacht at 6:15 p.m. during a ceremony . Up to this point in time, around 60 million tons of iron ore had been extracted, 14.7 million of them in open-cast mining.

After the cessation of operations, all shafts were filled and the day openings were closed. On August 24, 1983, the headframe of the Emiliesschachtes was dismantled. With that, the last landmark of the Pein mining industry disappeared.

Current condition (2010)

The best impression of the former Bülten-Adenstedt ore mine is given today by the buildings that have remained on the former mine sites.

The Kaiser-Wilhelm-Schacht is located west of Groß-Bülten a little outside the village at Schachtstraße 25 . The property is used by several businesses. The administration building, which housed the mine management during operating hours, is now the headquarters of Ilseder Mischwerke GmbH . Furthermore, a workshop and a storage building as well as a few outbuildings have been preserved there.

The Gerhardschacht is the most complete of all the shafts. Only the shaft hall with headframe and the loading were lost. The site is close to Kreisstraße 31, about halfway between Groß Bülten and Bülten. It is limited to the north by the Barbaraweg and to the south by the street Zum Gerhardschacht . The most striking building is the former hoisting machine house with the attached electrical center. Architecturally, the development repeats the design features of the Georg-Friedrich iron ore mine in Dörnten , which also belonged to the Ilseder Hütte.

The former Emilieschacht is located on the street of the same name on the eastern outskirts of Bülten. Most of the buildings were only demolished a few years ago after they were no longer used by Salzgitter AG. Basically there is only the administration / chews and the magazine.

A pulley of the Emilieschacht is erected as a memorial within Bülten.

literature

- Otto Bilges et al .: The lights are out - About the historic mining in the Peine district . Doris Bode Verlag, Haltern 1987, ISBN 3-925094-07-5 .

- Rainer Slotta : Technical monuments in the Federal Republic of Germany - Volume 5, Part 1: The iron ore mining . German Mining Museum, Bochum 1986.

Web links

- Colorful lime from Bülten-Adenstedt. In: bgr.bund.de. Retrieved July 14, 2016 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 18

- ↑ a b Slotta: Technical Monuments in the Federal Republic of Germany, Volume 5, Part 1 . 1986, p. 225

- ↑ a b c Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 19

- ↑ Geoscientific Collection of the Federal Institute for Raw Materials on www.bgr.bund.de ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved February 18, 2010

- ^ Mineralienatlas - Ramsdellite , accessed on February 18, 2010.

- ^ Mineralienatlas - Kutnohorit , accessed on February 18, 2010.

- ↑ a b Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 22

- ↑ Slotta: Technical Monuments in the Federal Republic of Germany, Volume 5, Part 1 . 1986, pp. 226-229

- ↑ a b c Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 23

- ↑ a b c d e f Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 24

- ↑ a b Slotta: Technical Monuments in the Federal Republic of Germany, Volume 5, Part 1 . 1986, p. 232

- ↑ Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 48

- ↑ a b c Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 27

- ↑ a b Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 76

- ↑ a b Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 34

- ↑ a b c d e f Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 28

- ↑ Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 53

- ↑ Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 57

- ↑ Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 39

- ↑ Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 82

- ↑ a b Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 31

- ↑ a b Slotta: Technical Monuments in the Federal Republic of Germany, Volume 5, Part 1 . 1986, p. 235

- ↑ ERZGRUBEN: Last shift . In: Der Spiegel . No. 50 , 1961 ( online ).

- ↑ Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 32

- ↑ Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 104

- ↑ a b c d Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 61

- ↑ Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, pp. 101-102

- ↑ Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, pp. 106/107

- ↑ Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 103

- ↑ Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 111

- ↑ a b Bilges et al .: The lights are out . 1987, p. 119

- ↑ Slotta: Technical Monuments in the Federal Republic of Germany, Volume 5, Part 1 . 1986, p. 236

- ↑ Slotta: Technical Monuments in the Federal Republic of Germany, Volume 5, Part 1 . 1986, pp. 236-238

- ↑ Slotta: Technical Monuments in the Federal Republic of Germany, Volume 5, Part 1 . 1986, p. 240