History of the Reformation in the Markgräflerland

The history of the Reformation in Markgräflerland largely follows the history of the Reformation in the margraviate of Baden-Durlach and reaches its climax with the introduction of a new church order by Margrave Karl II on June 1, 1556.

Demarcation

Under Markgraeflerland only the dominions previously belonging to the Margraviate of Baden-Durlach Rötteln and here Badenweiler and the Landgraviate Sausenburg understood. Within this area, however, there were some villages with Catholic manorial rule, in which the Catholic creed remained even after the new church order was introduced.

Early neighborhood influences

The Franciscan monk Bernardin Samson pushed the indulgence trade on a large scale in Switzerland, where he formed the counterpart to Johann Tetzel in Germany. The City Council of Basel prohibited him from working in the city. As early as 1517, Luther's writings were printed and distributed in Basel by Johann Froben with great success. Since Basel was the urban center for the Markgräflerland, it can be assumed that the population came into contact with the new ideas early on. In 1521/1522 Wilhelm Reublin was a leading head of the Swiss Anabaptists in Basel. In 1522, citizens of Freiburg im Breisgau asked the Bishop of Constance - without success - to be allowed to celebrate the Lord's Supper even after the Protestant confession. In 1522 Johannes Oekolampad settled in Basel. The Reformation also took hold early in Strasbourg , where Martin Bucer found asylum in 1523. Writings such as Karsthan's Reformation Dialogue were spread across the Upper Rhine. Bern's later co-reformer, Franz Kolb, came from Inzlingen , which belonged to the margravate. The reformer Johann Eberlin von Günzburg was in Rheinfelden for four weeks in 1523 , which he had to leave again due to the intervention of the local clergy. In 1524, the majority of Waldshut joined the Reformation . In 1525, under Balthasar Hubmaier, the Anabaptist direction prevailed.

Thomas Müntzer stayed in the Klettgau municipality of Grießen for a few weeks at the end of 1524 , after having previously visited Oekolampad in Basel . In this way radical ideas became known in the upper margraviate and found their way into the minds of the peasantry, who based their articles on these ideas in 1525. In the 12 articles of the peasantry, which were also accepted by the margravers, the demand was included: Free choice and removal of the pastor who should preach the Gospel without human additions - so a demand of the reformers was also included.

In 1527 Konstanz was reformed and subsequently joined the Schmalkaldic League . After a guild revolt , Basel joined the Reformation in 1529 .

The introduction of the new church order in 1556

Margrave Ernst closed the Sulzburg monastery in 1521 because of the grievances there. In 1522 he granted asylum to the evangelical pastor of Kenzingen , Jakob Otter . His court preacher Jakob Truckenbrot was a follower of Lutheran teaching.

After the Passau Treaty (1552), a number of secular rulers in southwest Germany introduced the Reformation. Margrave Ernst von Baden-Durlach is also said to have had plans for this, but shied away from a possible conflict with the regent of Catholic Front Austria , Archduke Ferdinand , who again registered his claims to areas of the Baden Oberland .

Margrave Karl II. - like his cousin Margrave Philibert of Baden-Baden - was very committed to the Augsburg Religious Peace of 1555 at the Reichstag , which allowed the secular imperial estates to introduce the Reformation. With this security and at the urging of Duke Christoph von Württemberg , Karl then dared to introduce the Reformation in the margraviate of Baden-Durlach by issuing a new church ordinance on June 1, 1556.

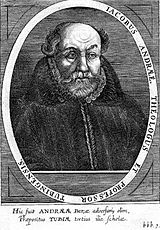

The preparation of the Reformation and the drafting of the church ordinance was entrusted to a commission chaired by the Chancellor of the Margraviate of Baden (Pforzheimer part), Martin Achtsynit . Members of the commission were the Tübingen theologian Jacob Andreae , the Saxon theologians Maximilian Mörlin and Johann Stössel , and the Heidelberg court preacher Michael Diller. In addition to the theologians, the commission included the margravial Baden court councilors Johann Sechel and Georg Renz. Achtsynit also became the first director of the council of churches; Karl himself was the regional bishop of the Protestant Church and thus succeeded the bishops of Strasbourg, Speyer and Constance who were previously responsible for parts of his rule. The “turmoil within the evangelical creed” also impaired the work of the commission. Ultimately, for political reasons, the church order of Württemberg, which was designed by Johannes Brenz in 1553, was largely adopted . For the first church visit , which was carried out in autumn 1556, Württemberg also made Jacob Heerbrand available, who was also involved in the final editing of the church regulations.

For the Baden Oberland , Karl appointed the Basel theologian Simon Sulzer as general superintendent . When the Reformation was introduced in the margraviate of Baden-Durlach , he played a major role in it. He ordained evangelical preachers for the area and carried out church visitations in 1556 . Thomas Grynaeus was installed as pastor in Rötteln and superintendent of the diocese of Rötteln in 1558 .

Frequent visitations were intended to ensure that only Lutheran pastors were active and that church regulations were observed. Numerous Catholic pastors were expelled.

The zeal that Karl developed with the introduction of the Reformation earned him the nickname “the pious” among the people. In 1561 the margrave confessed to the unchanged Augsburg denomination on the occasion of a gathering of Protestants in Naumburg organized by Elector August of Saxony .

Judging by the news available, the population accepted the Reformation ordered from above largely passively. Neither significant resistance nor enthusiasm has survived. For Zwingli's followers and the Anabaptists, the situation was hardly better than in Catholic areas.

Basel is pushing for the Reformation in Loerrach

After the city of Basel had taken over the Alban Monastery , it was also entitled to the parish in Lörrach belonging to this monastery . After this pastor's position became vacant at the beginning of 1556, the antistes of the Basel church, Simon Sulzer , arranged for his brother-in-law, the pastor and Professor Huldreich Koch (called Coccius), to give the first Protestant sermon in Lörrach in January 1556 - i.e. before the new one was introduced Church order. The first Protestant pastor in Lörrach was then Paul Strasser in 1556.

Catholic islands in the evangelical margravate

Within the margraviate there were some villages with Catholic manorial rule, in which the Catholic creed remained even after the introduction of the new church order:

The Basel mayor Heinrich Reich von Reichenstein († 1403) received high jurisdiction over Inzlingen in 1394 as a fiefdom from Margrave Rudolf III. transferred from Hachberg-Sausenberg . The empires of Reichenstein also had fiefs from the Habsburgs and the duchy of Basel and remained in the Catholic faith, which the residents of their village had to maintain. There are no known disputes with the margraves about this.

A special position had Ballrechten and Dottingen, which in 1458 by Margrave Charles I of Baden the Lords of Staufen as a fief has been sent. The Lords of Staufen , who belonged to the Upper Austrian provincial estates, remained with the Catholic denomination and, accordingly, their villages. Only after the Lords of Staufen died out in 1602, the margraves took back the fiefdom and both places were administered together with the old Badenweiler rule, whereby they remained Catholic.

The village of Stetten belonged to the women's monastery Säckingen , which remained as a state in front of Austria with the Catholic denomination. While no disputes about religious affiliation are known in the aforementioned cases, a conflict did arise in the Stetten case.

Margrave Rudolf III. von Hachberg-Sausenberg gained high jurisdiction over Stetten in 1409. The land and body rule remained with the Säckingen monastery and the lower jurisdiction lay with the Lords of Schönau . The margraves of Baden-Durlach as heirs of the Hachberg-Sausenberg family also claimed sovereignty over Stetten due to the high level of jurisdiction. The House of Habsburg, as the guardian of the women's monastery, defended this claim. The mixed situation of rights became explosive after the Reformation in the margraviate of Baden-Durlach.

Agatha Heggenzer von Wasserstelz was only elected abbess in 1550 and took over the monastery in a desolate state. After the protector, Emperor Karl V, died in 1558, Margrave Karl II saw an opportunity to gain sovereignty. In December 1559 the margrave sent a letter to the abbess in which it was announced that the appointment of a Protestant pastor was intended. The West Austrian government in Ensisheim denied Karl the right to do so in January 1561 because he was not the sovereign. When Karl sent a Protestant preacher to Stetten in February 1561 , he was standing in front of the locked church door. In April 1561, the Durlach Chancellor Martin Achtsynit and the Upper Austrian Chancellor Johann Ulrich Zasius agreed to keep the status quo and thus the Catholic creed in Stetten for the time being - a solution to the prelate dispute was more important at this time.

In the spring of 1564, the margrave again announced the appointment of a Protestant pastor and in November 1564 the first Protestant service was held - the Catholic pastor left the place. At the Augsburg Reichstag in 1566 a compromise was reached between Emperor Maximilian II and the Margrave. While the margrave was granted tax revenue, the emperor prevailed regarding the creed. In December 1566, the Säckingen abbess reinstated a Catholic priest, which ended the two-year Reformation interlude. The question of sovereignty remained unresolved.

The prelate dispute

As a result of the Reformation, only Lutheran pastors were allowed in the territory of the Margrave of Baden-Durlach. However, the church set was in many cases owned by Catholic monasteries and orders, which were now supposed to appoint and pay a Lutheran pastor, which of course provoked resistance. In the Augsburg Religious Peace this case was actually clearly regulated. On the one hand, they were allowed to keep and use their properties in Protestant areas, but had to pay for the maintenance of the Protestant pastors. Due to the sovereignty of the Habsburgs on the rulers of Upper Baden, however, the prelates believed that they would not have to fulfill the maintenance obligation for pastors and churches in the evangelical margraviate. Nevertheless, they wanted to keep the church tithe - the levy that was intended for the maintenance of the pastors. Karl therefore confiscated the prelates' goods and used them to finance the maintenance of pastors and churches. Johann Ulrich Zasius negotiated a compromise with Baden-Durlach, according to which the confiscated goods were released, but the funds necessary for the parish salary could be retained. However, the Austrian authorities in Innsbruck did not recognize this contract and escalated the dispute. After some prelates had reached a bilateral agreement with Baden-Durlach, general negotiations were resumed and on April 24, 1561 led to the Treaty of Neuchâtel am Rhein, which essentially followed the treaty already negotiated by Zasius.

The organization of the church in Markgräflerland

The Baden Oberland had its own general superintendent, to which the four dioceses and their special superintendents were subordinate. The three dioceses of Rötteln, Schopfheim and Badenweiler belonged to the Markgräflerland. The ecclesiastical structure followed that of the administrative units (Rötteln Rule, Badenweiler Rule and Landgrafschaft Sausenburg)

The secularization of the monasteries

At the time of the Reformation in 1556, there were no significant monasteries in the Markgräflerland. The Benedictine Monastery of Sulzburg , which had been repealed by Margrave Ernst in 1521 and revived again in 1548 , was repealed.

The offshoots of the St. Blasien monastery in Bürgeln , Sitzenkirch , Weitenau and Gutnau had not been revived or remained meaningless since the destruction in the Peasants' War and only represented goods of the monastery that it acquired through its contract of July 8, 1860 with the margrave also further secured.

Margrave Ernst moved the Antoniterkloster donated by Margrave Karl I in 1456 in Nimburg . 1545 after the monastery became impoverished and the monks moved away. He had a hospital set up there.

The elementary school - a child of the Reformation

The elementary school system in Baden is seen as the creation of the Reformation. Schools were financed from the church tithing, teachers were often the Sigrists and the pastors were responsible for supervision.

Article IV of the Durlach Church Order obliged the pastors to teach and explain the catechism every Sunday. The children should learn and understand it by heart. “The catechism was the historical starting point for elementary school instruction.” Accordingly, elementary school was initially a purely ecclesiastical matter. The teaching content was prescribed and controlled by the church, the school system was mainly financed by the church.

The visitations as a means in the fight against sects

As early as 1577, the guardian government decreed that a general visit was to be held annually in all lords. The theologians should review the visitation protocols promptly and report sectarian tendencies. Anabaptists and Schwenkfeldians in particular should be tracked down and returned to the Lutheran confession or expelled. In the diocese of Rötteln in particular, there were relatively many Anabaptists due to the contact with nearby Basel.

The dispute about the concord formula

The Duke of Württemberg had promoted the creation of the concord formula and, as a member of the Durlach guardianship government, was also interested in this principality accepting the formula. In the Durlachian Unterland and in the dioceses of Hachberg and Badenweiler, this was quickly enforced among the pastors, while there was considerable resistance in the dioceses of Rötteln and Schopfheim.

Simon Sulzer had joined Luther's teaching - especially in his view of the Lord's Supper - and thus distanced himself and the Basel Church from the Reformed Church in Switzerland. In the discussion about the acceptance of the concord formula in Basel and in the margraviate, Sulzer encountered the energetic resistance of Johann Jakob Grynaeus , who took the Zwinglian view on the question of the Lord's Supper . Due to this dispute, during the synod of the Diocese of Rötteln on October 29, 1577, no decision was made in favor of the concord formula. Instead, a new formula was proposed in a petition to the widowed Margravine Anna . The parish priests did not send the book with the formula of concord (Solida Declaratio) and in the new synod of October 29, 1577, the superintendent of the Hochberg diocese, Ruprecht Dürr, threatened that anyone who did not sign the formula in the margraviate would no longer be able to do so will be tolerated. Although the leaders of the opposition were not present and in view of the threats, the pastors only made a conditional signature on the formula and 10 pastors did not sign at all. During the church visit in May 1578, Johann Herbrand succeeded in persuading a number of pastors to sign an unconditional signature and the intercession of the Basel mayor largely protected those remaining after the conditional signature from negative consequences. These included the Binzen pastor and poet Paul Cherler , who paid for his initially oppositional stance with the loss of career opportunities. It is known from those who refused to sign any signature that the pastor of Maulburg got a new job in Riehen . The Schopfheim superintendent, Christoph Eichinger, emigrated and found a new job in Mulhouse in Alsace .

At the highest level, there was probably a lack of will for consistent implementation, as the two older sons of Margrave Karl, Ernst Friedrich and Jakob also refused to sign, which is attributed to the influence of the court preacher Georg Hanfeld and his successor Pistorius , who later reformed because of him Views was dismissed. The guardians acted for the princes, who, however, did not accept the concord formula for themselves when the government was handed over to them in 1584, although they formally sanctioned all acts of the guardianship government.

The conversion of Margrave Ernst Friedrich, who professed Calvinism in 1599 , left the Baden Oberland untouched, as Ernst Friedrich had ended his guardianship for the youngest brother, Georg Friedrich , in 1595 and Georg Friedrich - who had inherited the Oberland - always firmly with the Lutheran Confession remained. After his brother Ernst Friedrich converted to Calvinism, the strict Lutheran Georg Friedrich even set up his own grammar school in his small residence in Sulzburg in order to be independent of the now reformed grammar school in Durlach when training pastors . Under Georg Friedrich the formula of concord was enforced and pastors who deviated from the Lutheran line were dismissed.

The departure from Basel

Analogous to the political departure of the Free Imperial City of Basel from the Holy Roman Empire and its turn to Switzerland (Basel joined the Confederation in 1503), after the death of Simon Sulzer (1585) under Jakob Grynäus there was also a turn to the Reformed Church of Switzerland in the religious field, which ended with the accession of Basel to the Second Helvetic Denomination (1589) and led to a demarcation from the margraviate of Baden-Durlach.

Even before Sulzer's death, Grynäus' influence had risen and the majority of Swiss theology students at the University of Basel, as well as a proportion of the professors, were Zwinglians. The Baden-Durlach guardianship government had therefore not sent the theology students from the margraviate to Basel since 1579 , but to Tübingen . This severed the religious ties between Markgräflerland and Basel.

literature

- Rudolf Burger: The Reformation in Markgräflerland , Weil am Rhein 1984

- Rudolf Burger: The introduction of the Reformation in Markgräflerland 450 years ago . In: Das Markgräflerland, issue 2/2006, pp. 90–115 digitized version of the Freiburg University Library

- Karl Friedrich Vierordt : History of the Protestant Church in the Grand Duchy of Baden , 1st volume, Karlsruhe 1847, pp. 420–441 digitized

- Joseph Elble: The introduction of the Reformation in the Markgräflerland and in Hochberg. 1556-1561 ; in: Freiburg Diocesan Archive Volume 42 (1914), pp. 1–110 online at the University of Freiburg

- Karl Seith : The Markgräflerland and the Markgräfler in the Peasants' War of 1525. Karlsruhe 1926

- Heinrich Schreiber : The German Peasants' War - simultaneous documents , part I. Freiburg 1863, p. 179-184 ( digitized version )

- Gottlieb Linder: Ambrosius Kettenacker and the Reformation in Riehen-Bettingen: A New Contribution to the History of the Basel Reformation , Basel 1883

- Gottlieb Linder: Simon Sulzer and his share in the Reformation in the state of Baden: as well as in the efforts to unionize. Heidelberg 1890 Internet Archive

- JR Lindner: Outline of the life of Simon Sulzer. In: Journal for the entire Lutheran theology and church. 30, 1869, pp. 666-689. online at the University Library of Tübingen

- Paul Tschackert : Sulzer, Simon . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 37, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1894, p. 154 f.

- Erich Wenneker: SULZER, Simon. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 11, Bautz, Herzberg 1996, ISBN 3-88309-064-6 , Sp. 252-255.

- Real Encyclopedia for Protestant Theology and Church . Vol. 19, pp. 159-162.

- A. Baumhauer: The introduction of the Reformation in the upper margraviate . In: Badische Heimat 35 (1955) pp. 214–220 online from Badische Heimat PDF 769KB; accessed on April 18, 2019

- Karl Hammer : The Reformation in the Markgräflerland: (1556-1981) . In: Das Markgräflerland, issue 1/1983, pp. 109–114 digitized version of the Freiburg University Library

- Klaus Schubring : Reformation from below or Reformation from above? : the example of the Markgräflerland . In: Access to Martin Luther - Frankfurt am Main 1997. - pp. 183–203

- Christian Martin Vortisch: Thoughts on the iconoclasm in the Reformation . In: Das Markgräflerland, issue 1/1984, pp. 92–93 digitized version of the Freiburg University Library

- Christian Martin Vortisch: The programmatic declaration of the Markgräfler landscape in the Peasants' War in 1525 (probably in April) . In: Das Markgräflerland, issue 1/1985, pp. 163–165, digital copy of the Freiburg University Library

- Friedrich Holdermann : Harbingers of the Reformation - From: "From the story of Rötteln" . In: Das Markgräflerland, Volume 1/2001, pp. 74–78; Gerhard Moehring , Otto Wittmann , Ludwig Eisinger; History Association Markgräflerland eV (Ed.): 1250 years Röttler Church: 751–2001 , Uehlin, Schopfheim 2001, ISBN 3-932738-17-9 . Digitized version of the Freiburg University Library

- Ludwig Eisinger: On the church history of our homeland . In: Das Markgräflerland, Volume 1/2001, pp. 79-133; Gerhard Moehring , Otto Wittmann , Ludwig Eisinger; History Association Markgräflerland eV (Ed.): 1250 years Röttler Church: 751–2001 , Uehlin, Schopfheim 2001, ISBN 3-932738-17-9 . Digitized version of the Freiburg University Library

- Gerhard Moehring : The dispute between Simon Sulzer and Johann Jacob Grynäus . In: Das Markgräflerland, Volume 1/2001, pp. 211-217; Gerhard Moehring, Otto Wittmann , Ludwig Eisinger; History Association Markgräflerland eV (Ed.): 1250 years Röttler Church: 751–2001 , Uehlin, Schopfheim 2001, ISBN 3-932738-17-9 . Digitized version of the Freiburg University Library

- Heinrich Julius Holtzmann : The year 1556, the year of the Reformation in the countries that now form the Grand Duchy of Baden , 1856

- Stefan Suter: Why Inzlingen remained Catholic after the Reformation . In: Das Markgräflerland, Volume 2/1999, pp. 20-29, digitized version of the Freiburg University Library

- Karl Mühlhäußer: The elementary school in the former margraviate of Baden-Durlach . In: Journal for the history of the Upper Rhine , Volume 23, 1871, pp. 67–89 and pp. 205–262 Google digitized

- Paul Rothmund: Reformation in Baden-Durlach . In: Lörrach , 1982, pp. 216-220

- Karl Herbster : Basel and the Reformation in Loerrach . In: Karl Herbster: Lörracher historical memories . Rebmann-Verlag, Lörrach 1948, pp. 25–31 in the Internet Archive

- Eduard Martini: Some as yet little-known files on the history of the reform of the Badenweiler rule. In: Journal of the Society for the Promotion of History, Antiquity and Folklore of Freiburg, the Breisgau and the adjacent landscapes, first volume, Freiburg im Breisgau 1869, pp. 253-298 online in the Google book search

- Udo Wennemuth (Ed.): 450 years of the Reformation in Baden and the Electoral Palatinate . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-17-020722-6 .

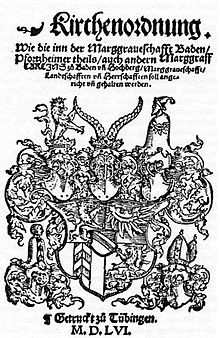

The church ordinance of 1556

- Church regulations such as the inn der Marggrave create Baden, Pfortzheimer partly, also other Marggrff. Carlins ... to be held ; Tübingen 1556 online at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek digital

Concord Book

- JT Müller: The symbolic books of the Evangelical Lutheran Church, German and Latin , Gütersloh 1890, 7th edition of the so-called Konkordienbuch - online in the Internet Archive; accessed on June 30, 2013 (PDF; 105 MB)

- Concordia: Christian, repeated, unanimous confession of subsequent electoral princes, princes and Stende of the Augspurgian Confession and the same theologians Lere and Faith. With attached, in God's Word, as the one guideline, well-founded explanation of several articles, in which after Martin Luther's blissful wither away disputation and dispute occurred ... Concord book edition 1580 in the Google book search

Web links

- Thomas K. Kuhn : Sulzer, Simon. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Entry Martin_Achtsynit in Stadtwiki Pforzheim; Retrieved June 25, 2013

- Reformation Markgräflerland on Leo-bw

- Thomas Müntzer in Klettgau PDF 282.7 kB; Retrieved June 29, 2013

Individual evidence

- ↑ s. Heinrich Schreiber : History of the city and University of Freiburg im Breisgau (IV. Delivery: Freiburg under its counts) , 1857 online at the University of Freiburg

- ↑ online in the Google book search [1]

- ↑ Thomas Müntzer in Klettgau PDF 282.7 kB; accessed June 29, 2013 ; s. also Vierordt IS 202-206

- ↑ s. Burger p. 24

- ↑ s. Vierordt p. 429

- ↑ s. Burger p. 27

- ↑ s. Burger p. 27

- ↑ s. Baumhauer p. 217/218

- ↑ s. Ball rights on leobw

- ↑ s. Dottingen on leobw

- ↑ Regesten the Margrave of Baden and Hachberg 1050 - 1515 , published by the Baden Historical Commission, edited by Richard Fester , Innsbruck 1892 Volume 1, certificate number H913 online

- ↑ z. B. St. Blasien , All Saints' Day, St. Peter, Schuttern, Tennenbach, Waldkirch

- ↑ z. B. the Teutonic Order

- ↑ s. Burger pp. 65-70

- ↑ the fourth diocese was Hochberg (Emmendingen)

- ↑ this corresponded to the diocese of Schopfheim

- ↑ s. Entry on kloester-bw

- ↑ s. Benedictine provost of Bürgeln in the database of monasteries in Baden-Württemberg of the Baden-Württemberg State Archives and entry of Schloss Bürgeln in the Baden-Württemberg location database on discover regional studies online (leobw)

- ↑ s. Benedictine convent Sitzenkirch in the database of monasteries in Baden-Wuerttemberg of the Baden-Wuerttemberg state archive and entry on Discover regional studies online - leobw

- ↑ s. Benedictine Provosty Gutnau in the database of monasteries in Baden-Württemberg of the Baden-Württemberg State Archives and entry on discover regional studies online - leobw

- ↑ s. Elble p. 97

- ↑ s. Antoniterhaus Nimburg in the database of monasteries in Baden-Württemberg of the Baden-Württemberg State Archives

- ↑ s. Eberlin p. 37

- ↑ s. Mühlhäußer (p. 69) who states this not only for Baden-Durlach, but in general and ascribes a pioneering role to Southwest Germany.

- ↑ Since the death of his father, a guardianship government with his mother Anna, Elector Ludwig VI. of the Palatinate (until 1583), Duke Philipp Ludwig von Pfalz-Neuburg and Duke Ludwig von Württemberg ("the Pious") exercised the business of government.

- ↑ s. Baumann p. 13

- ↑ Latin: Formula Concordiae; Text of the concord formula (Epitome, German) ; there is a short version of the Formula Concordiae (Latin: Epitome) and the detailed version (Latin: Solida Declaratio = "unanimous declaration")

- ↑ the addition they added contained the sentence we do not condemn those who think differently! with which the dialogue with the Reformed should be kept open

- ↑ s. also Karl Tschamber : Friedlingen and Hiltelingen. A contribution to the history of the Ödungen im Badischen Lande , Hüningen 1900, pp. 131-133

- ↑ s. August Eberlin: History of the City of Schopfheim , reprint of the edition from 1878, Schopfheim 1983S. 34

- ↑ Werner Baumann: Ernst Friedrich von Baden-Durlach, Stuttgart 1962, p. 17

- ↑ s. Gothein p. 50