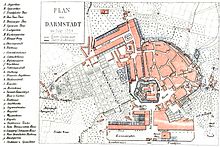

History of the city of Darmstadt

The city of Darmstadt emerged from a Franconian settlement in the Middle Ages . After the division of Hesse in the 16th century, Darmstadt became the residential city and political center of the Landgraviate of Hessen-Darmstadt , in the 19th century the capital of the Grand Duchy of Hesse , after the end of the German Empire the capital of the People's State of Hesse . With the founding of the state of Hesse , the political and administrative importance declined, as the larger Wiesbaden , which was hardly destroyed, was given preference as the state capital.

Prehistory (up to approx. 800 AD)

From the Neolithic Age up to the first millennium AD, settlement activities in the Darmstadt area are documented through finds, graves and grave goods. In contrast to later epochs, this early settlement history was more determined by geographical conditions. The natural spatial basis of the settlement area is shaped by its location in the area of the Upper Rhine mountain system. Its northern branch, the Odenwald , which runs out before Darmstadt , merges to the north to the plain, but has a pronounced edge to the west. Between this and the Rhine flowing in the west, a natural path of peoples, the mountain road, was formed . In addition to the location of the area at the northern end of this route and other favorable, naturally given paths, the silted up meanders of the old rivers of the Rhine and Neckar , which originally united at the height of Trebur , were decisive. Sand deposits were blown into dunes as early as the Ice Age , which in many places still form the transition from the Rhine plain to the Odenwald. These dunes and headlands were flood-proof and thus offered the possibility of permanent settlement.

Few individual finds prove a human culture from the fifth and fourth millennium BC. Agricultural farmers of the band ceramics culture moved down from the Wetterau and left individual traces. The following, the so-called Rössen culture , probably also immigrated from the Wetterau. The Michelsberg culture that seeped in from the south in low density left the fewest evidence. For all three Neolithic arable cultures, the importance and significance are difficult to assess because of the low density of finds.

From around 2000 BC The most important population groups in transition to metalworking, the cord ceramists and the bell-beaker people , can be identified. The former, also called battle ax people , extended from Thuringia to the Main area and ousted the indigenous population through their military superiority. The burial mound introduced by them can be traced north of Arheilgen and in Kranichstein . Around the same time, the bell beaker people, for whom the first copper utensils are typical, immigrated from Western Europe. The interpretation of numerous finds suggests that these in turn displaced the battle ax people from the Darmstadt area. An important burial ground was found in 1926. The best-preserved deceased, a young man buried in the typical stool position, can be found today as the “Elder Darmstadt” in the Hessian State Museum in Darmstadt .

From the early Bronze Age , around 1600 to 1200 BC. BC, the population group of the Barrow Bronze Age can be proven in large numbers by their specific type of burial - burial in elongated form under artificial mounds. Rich pottery, jewelry and weapons finds, including amber additions from the Baltic Sea coast or arm warmers from Silesia , indicate the first cultural bloom. In Wixhausen the first house traces have been found from this period.

There was a complete change in the image of culture from 1200 BC. Through social shifts. The predominant pasture farming was replaced by agriculture, from then on the dead were burned and their ashes were buried in urn fields. The urn field culture named after it had a high level of technical ability, which is proven by the richer finds of utility ceramics and also the art of jewelry and weapons.

From village to town and secondary residence (approx. 800 to 1479)

Origins (c. 800 AD - 1330 AD)

The place Darmstadt was probably the 8th or 9th century by the Franks founded. From this point on, the area was undoubtedly continuously populated. However, Darmstadt did not enter history until the end of the 11th century: Count Sigebodo, a member of the noble family of the Reginbodones , had levied interest on the Darmundestat .

At first Darmstadt belonged to the Wildbann Dreieich . After the village, as part of the County of Bessungen, fell into the possession of the diocese of Worms in 1002 and the possession of the diocese of Bamberg in 1009 , it finally became a fiefdom of the diocese of Würzburg on June 21, 1013 , which remained Darmstadt until the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss 1803.

In the middle of the 13th century, the Counts of Katzenelnbogen near Darmstadt built a moated castle . For defense, knights gradually settled south of the castle. Since the original, rural population lived east of the castle, two settlement cores separated from the Darmbach formed , which were probably originally administered separately.

City charter and construction of the wall (1330–1479)

On July 23, 1330, Emperor Ludwig granted the Bavarian Count Wilhelm I. von Katzenelnbogen the city rights for Darmstadt. This privilege was given to the count exclusively personally; the city itself, neither its citizens nor the local knightly nobility, could derive any justification from it. With the associated market law, however, the importance of the previously rather inconspicuous settlement grew rapidly and the entire economy in the area was oriented towards the Darmstadt market, while Darmstadt itself oriented itself towards the older and larger cities of Frankfurt am Main , Worms and Speyer .

Darmstadt is located directly on the northern part of Bergstrasse, which gives the city an immense economic advantage over other cities in the region such as B. Reinheim , which soon after the city charter was granted to Darmstadt in political importance. In addition, Darmstadt was probably at least partially fortified as early as the Frankish times. With the construction of the moated castle at the latest, however, the Counts of Katzenelnbogen preferred Darmstadt to Bessungen , which was also directly on Bergstrasse, which had been more important to date . The combination of these two factors, the favorable location directly on the Bergstrasse and fortification by a moated castle, were the cornerstone for the economic and political upswing that the city experienced during the Katzenelnbogen period.

In the following period after the city charter was granted, only the inner ring of the city wall was built little by little, which strictly limited the area of the city and, due to the lack of space in the steadily growing city, ensured that the two settlement centers gradually grew together. Around a hundred years passed before the city wall with the inner and outer ring was completed.

The self-government of the city was guaranteed by a fourteen-member jury chaired by a mayor . This rather unusual number for a civic council (numbers of representatives with religious references such as seven or twelve were common) indicate the great social distance between the rural upper and the noble lower village. It can be assumed that originally only seven lay judges administered the upper village and that this number was simply doubled when the lower village was founded as living space for the Burgmannen.

The city administration was firmly in the hands of a few families who held their office for life and were mostly inherited by family members. There are some indications that this order has created tension in the village. Apparently the citizens felt that their interests were not adequately represented in this way. In order to take into account the will of the citizens, Count Philipp the Elder von Katzenelnbogen ordered in 1457 that the size of the city administration be expanded by another fourteen people, all of whom were to be elected from the community. The influence of the already existing lay jury was obviously so great that this order only became reality in a weakened form, when the office of the "four-man" was introduced. As the name suggests, this committee, consisting of four people, was henceforth representing the interests of the citizens. They were elected directly by the citizens.

In the course of the 14th and 15th centuries, the Counts of Katzenelnbogen continued to expand and remodel the castle until it finally became a representative castle in the middle of the 15th century. Darmstadt became Katzenelnbogen's secondary residence and experienced a first high phase of its development, while Countess Else von Katzenelnbogen established a “princely” court in 1385 on her widow's residence. After the early death of Count Philip the Younger in February 1453 in Darmstadt Castle, his widow, Countess Ottilie, ran the farm with two cooks, two bakers, a butcher, falconers, dog handlers, bird operators, otter catchers, a coat of arms master and many court musicians.

In 1479 the dynasty of the Counts von Katzenelnbogen died out, and Darmstadt fell to Heinrich III. from Hessen and stagnated for decades. Despite the castle and city wall, the social structure still corresponded more to that of an arable village. This is also borne out by the history of the Princely Hofmeierei, the Oberfeld estate in Darmstadt.

Landgraviate (1479–1806)

The last years of a unified Hessen (1479–1567)

After the death of the last Count von Katzenelnbogen, Darmstadt fell to Landgrave Heinrich III. of Hessen. As a result, Darmstadt's reputation sank from an important secondary residence to a small outpost far from the Hessian center of power Kassel . The most significant event of this early phase in the Landgraviate is likely to be the confirmation of all city privileges by Landgrave Wilhelm III. on August 10, 1489. Contrary to the previous regulation, town and market law was no longer tied to the ruling count, but was under the administration of the town itself. In return, the town had to support the landgrave economically, for example as security for debtors. The temporarily poor financial situation of the Landgraviate was partly passed on to Darmstadt, which suffered economic damage due to these debts.

Far-reaching changes for Darmstadt began when Landgrave Philipp the Magnanimous came to power in 1518. In the same year Franz von Sickingen attacked the city. The still relatively young city wall turned out to be technically hopelessly outdated and could not withstand the siege for long. The castle was destroyed for the first time and the city was subsequently busy rebuilding the destroyed buildings. However, they only restored the status as it existed before the attack and, fatally, refrained from extensive modernization of the defenses. Just a few years later, in 1547, Darmstadt was stormed by imperial troops as part of the Schmalkaldic War . Large parts of the castle and the city were destroyed again.

One of the causes of this war was the split in the church . Landgrave Philip the Magnanimous had introduced 1527 in Hesse, the Reformation and thus outlawing Emperor Charles V is acting. The consequences of this dispute caused Darmstadt to continue to stagnate, although Landgrave Philipp tried much more than his predecessors to strengthen Darmstadt's economic power. The political importance also increased again, several conferences and diplomatic negotiations took place in Darmstadt during Philip's reign.

Domestically, there was still a big difference between the city administration and the citizenry. Many offices were awarded twice. For example, there were always two mayors, a so-called "council mayor" (later mayor) who was elected by the council members for a year, and a "younger" mayor or sub-mayor who was also elected by the mayor for a year. So there were still tensions between the city council and the citizens, who did not see themselves adequately represented in the council.

Founding phase of Hessen-Darmstadt (1567–1596)

When Landgrave Philipp the Magnanimous died in 1567, Hesse was divided among his four sons. Landgrave Georg I (the pious) then founded the Hessian branch line Hessen-Darmstadt and turned the former Darmstadt outpost into a handsome residential town.

Initially still under the tutelage of his brother Ludwig IV of Hessen-Marburg , the reconstruction of the palace and the construction of the new town hall were completed, and craft and trade regulations were issued. Georg himself then consolidated the budget, reorganized the administration, reformed and centralized the judiciary and massively expanded the city. This is how the old suburb in Magdalenenstrasse came into being from 1590. The castle was also expanded.

In terms of foreign policy, Darmstadt experienced positive times and was spared wars during the reign of George I. As a result, the city's economy, prosperity and population grew rapidly. He made school attendance a prerequisite for confirmation and thus de facto introduced compulsory schooling . In 1591, after many years of negotiations with his brothers that ultimately failed, he finally sealed the final division and sovereignty of Hesse-Darmstadt from the other former Hessian areas of Philip the Magnanimous with the implementation of the land law drawn up by his Chancellor Johann Kleinschmidt . Darmstadt was thus irrevocably the permanent capital of the dominion of George's dynasty, even when later large parts of the original Hesse were reunited under the rule of the Grand Dukes.

From 1582 at the latest, however, the social tensions in the city increased when the population was seized by the witch hysteria, as a result of which around 40 women and a boy named Wolf Weber were convicted and executed as witches . Also in that decade there were repeated outbreaks of the plague , from which more than 10% of the city's population died in 1585 alone.

The latter, however, also prompted Georg to create the first elements of a social system by setting up a municipal poorhouse in 1592 and teaching orphans in the castle from 1594.

Despite the witch hunts and the plague wave, the population doubled during Georg's tenure.

Thirty Years War, Plague and Famine (1597–1661)

Georg's son and successor Ludwig V (the faithful) initially continued the expansion work and new buildings that his father had started, so that Darmstadt continued to grow. The inheritance dispute with Hessen-Kassel over the inheritance of Hessen-Marburg , which began in 1604, but above all the outbreak of the Thirty Years War in 1618, hit Darmstadt hard and led the city through several crises.

From 1630 this got worse after Landgrave Wilhelm V of Hessen-Kassel allied himself with the Swedish King Gustav Adolf during the war . Since the Darmstadt Landgrave, now Ludwig's son Georg II , was on the emperor's side, the Swedes supported Hessen-Kassel in the dispute over the Marburg inheritance. This in turn called the emperor onto the scene, who in turn rushed to help George II. Georg then left Darmstadt for Gießen because he believed he was better protected there. He did not return until 1649, after the end of the war.

When George II took office in 1626, the situation of the minorities residing in the city, especially the Jews, also changed . Although discriminated so far, as everywhere in the Reich, they had nonetheless chartered rights since the reign of George I and were allowed to pursue their respective trades relatively easily. The war, however, exacerbated the relationship between Jews and Christians, since in the tense economic situation the Jews became unpleasant competition.

Immediately after taking office, George II asked all Jews to leave the country. He was supported by the city council, which called for the "abolition of the Jews", whereupon Georg set the Jews a deadline of August 1, 1627, after which no Jew should "be seen at Darmstadt". However, supported by a ruling by the Reich Chamber of Commerce, which confirmed their legal status, the Jews successfully defended themselves against the expulsion, so that Georg granted them their rights again with the Jewish Code of February 20, 1629, albeit with severe restrictions.

After the plague broke out again in Darmstadt in the winter of 1632/33 and claimed more than 2,000 victims by 1635, the French occupied the city without a fight for a few weeks in the same year, causing great damage, looting the surrounding villages and in some cases burning them down . The fields were also devastated. There was famine. In 1639 the city was taken again, this time by Bavarian troops, and again the city was devastated.

While the Landgrave stayed in safe Giessen, the situation in Darmstadt worsened. Refugees from the surrounding villages fled into the supposedly safe city walls and thus provided new breeding ground for the plague. In April 1647, French troops again entered the city without a fight. Their supply brought Darmstadt to the brink of ruin, so that even the city council officially predicted the impoverished citizen's approaching demise. The good location on Bergstrasse, which had once favored the rise of Darmstadt, now became the city's undoing, as the troops that were constantly moving through were billeted in the city and economically pushed to the limit.

Only at the end of the war through the Peace of Westphalia did Darmstadt slowly begin to recover. The immediate post-war period was characterized by slow reconstruction and petty disputes over property between the landgrave and the city council. The latter felt that the Landgrave was increasingly restricting his rights, a foretaste of the impending absolutism.

Peace and renewed upswing (1661–1688)

With Ludwig VI. returned from 1661 not only a time of peace, but also of economic boom. Construction activity increased again and prosperity spread. Since Georg II had joined the Rhenish Alliance in 1659 , foreign policy tensions arose again and again, which made an improvement of Darmstadt's defenses appear necessary. Ludwig had plans drawn up to convert Darmstadt into a Sternschanzen fortress . Ultimately, however, only minor improvements were made to the city's defenses.

Ludwig continued the increase in princely privileges that his predecessor had begun. The almost complete disempowerment of the central court severely restricted the rights of the city administration. The establishment of a right of election for the landgrave at every election of the city council was even more difficult . The Landgrave could freely choose which proposed candidate he confirmed, making the election by the council members superfluous. With a later introduced right of proposal , the Landgrave de facto completely determined the occupation of the city council.

Louis VI. died on April 24, 1678. Since his son and successor Louis VII. only a few months after a Ruhr succumbed to infection and the next in succession, Landgraf Ernst Ludwig was only 10 years old, whose mother, took Elisabeth Dorothea of Saxe-Gotha -Altenburg the business of government. She continued the positive development of the city through her deceased husband and, among other things, had the suburbs completed.

Absolutistic lack of proportion, economic decline and first cultural prosperity (1688–1790)

When Ernst Ludwig finally took over government himself in 1688, the foreign policy situation deteriorated. Again there was a threat of inheritance disputes, so that Ernst Ludwig left the city, which was still poorly protected, and, like Georg II, ruled from Giessen. He tried to enforce the principles of absolutism in his state , which for Darmstadt meant that the rights of the city council were further restricted.

In 1693 the French attacked Darmstadt and destroyed the castle keep and parts of the city wall around the White Tower. This is exactly where Ernst Ludwig had the “new suburb” built from 1695. Darmstadt finally changed structurally from an arable town to a residential town.

In 1698 the foreign policy situation eased and Ernst Ludwig returned to Darmstadt with his court. He had already started to expand the city some time before. In addition, he also ordered the construction of numerous representative buildings. After the chancellery of the castle burned down in 1715, Ernst Ludwig had Louis Remy de la Fosse , who had already designed the orangery in Bessungen, plan a new baroque castle with four large wings to completely replace the old one. Due to financial difficulties, only two wings were completed by 1726.

In addition, Ernst Ludwig carried out numerous political reforms. He planned the settlement of Huguenots , allowed - despite considerable opposition from the city council - the Jews to carry out religious services and later even the establishment of a synagogue and even Catholics were allowed to hold private worship services at times, a touch of enlightenment in the midst of absolutism.

However, Ernst Ludwig also ruled far beyond his means and led the country to almost ruin. At the end of his life, the financial situation was so catastrophic that the landgrave even employed alchemists to produce gold for him from lead. Of course, this only caused additional costs. At his death in 1739 the national debt amounted to over 4 million guilders.

Ernst Ludwig's successor Ludwig VIII stopped the further expansion of the city for the most part. However, he expanded the hunting apparatus at great expense. Ernst Ludwig had already wasted large sums of money with his passion for hunting and made large parts of the land unusable. With Louis VIII this was intensified and only further ruined the state finances, not to mention the further destruction of large areas of land, which thereby became unusable for agriculture.

Louis IX , who took up the office of landgrave in 1768, ordered the country to implement rigorous austerity measures. For Darmstadt the reign of Ludwig IX. a time of reforms and political insignificance, since Ludwig moved the seat of government to Pirmasens , where he had resided as Count von Hanau-Lichtenberg since 1741 .

Ludwig's wife, Karoline von Hessen-Darmstadt , who, unlike her husband, often resided in Darmstadt, ensured the first cultural heyday of Darmstadt. From 1771 she gathered the so-called “ Circle of Sensitive People ”, to which the young Goethe belonged , among others . This gave her the honorary title The Great Landgrave .

The Landgrave, on the other hand, invested a large part of the state budget in the military. For his concerns, he hardly considered the difficult financial situation and had, for example, a drill house in Darmstadt that was only completed in 1769 torn down again in order to have a new, even larger one built. In return, he massively reduced the holding of court, sold the hunting castles of his ancestors and restricted the music and theater business. He hardly visited Darmstadt after 1772, but ruled with written decrees from Pirmasens.

The city's situation was desolate at the end of the 19th century:

“ When the current prince [ Grand Duke Ludwig I of Hesse-Darmstadt ] took office in 1790, it [the city of Darmstadt] was still an insignificant, old Franconian and dirty little town with at most 700 unsightly houses, at which residence, strange enough , the country road passed . "

Grand Duchy of Hesse (1806–1918)

End of the Landgraviate and beginning of the Grand Duchy (1790-1815)

Ludwig X took over rule in 1790 and moved the seat of government back to Darmstadt. Committed to the Enlightenment, right at the beginning of his term of office he allowed Catholics to practice their religion freely and without restrictions. A few years later, he also allowed Jews to acquire real estate. In 1796 the first Jew received citizenship.

With the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss 1803 Hessen-Darmstadt gained large areas. In 1806, Landgrave Ludwig joined the Confederation of the Rhine and was appointed Grand Duke by Napoleon I. Since then he has called himself Ludewig I. von Hessen-Darmstadt and bei Rhein .

Under the first Grand Duke, population growth increased sharply and Georg Moller began building the " Mollerstadt " west of the castle in 1810 , which was quickly occupied by the socially better off population, while the old town became impoverished and impoverished. Moller also built some representative buildings such as the Hof Opera Theater at Herrngarten, today's Hessian State Archives in Darmstadt and the Ludwig Church.

Vormärz and industrialization (1815–1871)

Grand Duke Ludewig I initially adhered to absolutism, but in 1820 he introduced a state constitution that introduced a bicameral system and defined debt reduction as a constitutional goal. The electoral system was complicated and still far from being democratic. Eligible to vote were those who were male, at least 25 years old and who paid at least 20 guilders direct taxes. That was about 15% of the citizens of Darmstadt, who first elected a group of proxy, who in turn determined electors who made the actual election. To make matters worse, one could only become a member of the state parliament if one paid at least 100 guilders direct taxes. In Darmstadt there were no more than 20 people.

Nevertheless, the Grand Duke initially seemed able to dampen the effects of the Vormärz . When his son Ludwig II came to power in 1830, however, the revolutionary ideas also became more and more popular in Darmstadt.

The initially apolitical newspapers turned more and more to the politics of the day, until the Hessische Landbote , written by Georg Büchner and revised by Friedrich Ludwig Weidig , went to print in June 1834 , in which the grand ducal government and the nobility sharply criticized the grand ducal government and the famous slogan “Peace the huts! War on the Palaces! ”Was called for revolution.

The unloved Grand Duke Ludwig II tried with nostalgia to benefit from his father's good reputation among the people and had a huge monument erected on Luisenplatz in his memory, the Ludwigsmonument , popularly known as "Langer Ludwig". At the height of this phase of local patriotism, the proposal was even made to rename Darmstadt Ludwigsstadt. The derisive comments of the liberal forces on this suggestion also indicate that the urge for revolutionary ideas could not be suppressed by such magnificent buildings as the Ludwigsmonument alone.

When the unrest in the population grew larger and more violent at the beginning of 1848, Grand Duke Ludwig II appointed his son Ludwig III. on March 5, 1848 as co-regent. As a result of the March Revolution of 1848, with the "Law on the Relationships of the Classes and Noble Court Lords" of April 15, 1848, the special rights of the class were finally repealed. Ludwig III. was very popular with the people and after he became sole regent on June 16, 1848 after the death of his father, he was able to successfully defend the prominent position of the Grand Duke against the emerging democratic and socialist ideas.

On October 9, 1850, Ludwig III, once the great hope of the democracy movement, introduced three-class voting rights based on the Prussian model, which in fact restricted the liberal movements even more and made clear the reactionary orientation of the Grand Duke after 1848.

In the period that followed, industrialization in particular provided the city with an upswing. As a result, the impoverishment in the slums was temporarily stopped, which also took the wind out of the sails of the revolution. In 1848, for example, the Merck chemical factory built its first factory on today's Mercksplatz.

German Empire and First World War (1871–1918)

In the founding phase of the German Empire , the economy continued to flourish and the city grew so immensely that Bessungen was incorporated into Darmstadt in 1888.

As early as 1874, Darmstadt received a new urban code. The city council meeting, which has been significantly expanded in its self-administration rights, was now elected by all residents of the city for more than two years with equal voting rights.

Outside the old town, which continues to deteriorate, new, representative buildings, the museum, universities and completely new settlement areas were built. The most famous is the artists' colony founded by Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig on Mathildenhöhe in 1899 , which developed into one of the centers of Art Nouveau .

The last decade of the 19th century was marked by economic upswing, population growth and a revival of art and culture, even if the state parliament viewed the latter with skepticism. Above all, the one-sided promotion of a certain art direction instead of the "arts and crafts" itself caused criticism. The necessity of the artist colony was in any case closed to the “simple” Darmstadt citizens. As early as 1904, the then city architect August Buxbaum noted with satisfaction (albeit erroneously): “Art Nouveau has been overcome”, a clear sign that Ernst Ludwig's artistic ambitions met with less approval from his contemporaries than the later proud definition of Darmstadt as an Art Nouveau city suggests.

Even before the outbreak of World War I , construction activity sank and the war itself brought any upswing to a standstill. Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig largely ignored the political developments and fell into artistic enthusiasm and unreality. After the November Revolution of 1918 he refused to abdicate. Nevertheless, Darmstadt became the capital of the newly founded state of Hesse with a republican constitution.

Recent history (from 1918)

Weimar Republic

After the war, Darmstadt's development ran parallel to that of the rest of the country. Economic crises, interrupted by brief booms, led to food shortages, high unemployment and social tensions. To make matters worse, there was an acute housing shortage, which, despite numerous new buildings, could not be mastered. With the onset of the global economic crisis , the situation worsened (as before, especially in the old town).

From 1930 the steep rise of the National Socialists began in Darmstadt . In 1931 they received significantly more votes than the national average in the state elections in Darmstadt. The previous political supremacy of the SPD , which clearly lost votes, was broken and several, in some cases violent, demonstrations by social democrats, communists and other representatives of the workers' and democracy movement could no longer change anything on the way to fascism .

After the spontaneous protest marches of the KPD and SPD on the evening of January 30, 1933 , when Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor , there were cross-party demonstrations and rallies in the following weeks, including a general strike as a political means against the new ones Rulers were considered. However, this protest movement ended with the Reichstag election on March 5, 1933 , in which 50% of Darmstadt's residents voted for the NSDAP .

National Socialism and World War II

After the election in March 1933, there were immediate arbitrary arrests of political opponents of the National Socialists. Mass searches of houses and the dismissal of “Republic-friendly”, “Jewish” and “non-Aryan” officials were also part of a targeted harmonization campaign. Streets and squares were renamed in line with the new ideology. B. from the Rathenau -anlage the Horst-Wessel -anlage and from the Luisenplatz the Adolf-Hitler-Platz . Critical newspapers were banned.

On March 13th, the Hessian state parliament voted with the votes of the NSDAP and the center, the NSDAP politician Ferdinand Werner as the successor to Bernhard Adelung as the new president of the people state of Hesse. The SPD MPs no longer took part in this meeting after massive threats from the National Socialists.

In 1937 Darmstadt became a major city by incorporating Eberstadt and Arheilgen. In addition, u. a. the Griesheim military training area with the airfield and the Tann settlement in Darmstadt, a total of 7.8 km² of Griesheims (approx. 25%) came to Darmstadt.

With the Cambrai-Fritsch barracks , the bodyguard barracks, the Ernst-Ludwig barracks and the Garde-Dragoon barracks , five new barracks were also built. The synagogues in Bleichstrasse, Friedrichstrasse and Eberstadt burned during the Reichspogromnacht from November 9th to 10th, 1938 . At dawn (in contrast to the arson attacks at night, possibly unorganized) SA and SS commandos marched through the streets and blindly destroyed numerous Jewish shops and institutions. This also caused deaths to be lamented. For example, a Jewish girl rushed out of the window in a panic when the SA troops approached, whereupon her father hanged himself in despair in shock.

On June 8, 1940, Darmstadt experienced the first of a total of 36 bomb attacks. From the summer of 1943, attacks took place on a daily basis until the air raid on Darmstadt on 11/12. September 1944 - on the so-called fire night - the city was turned into a desert of rubble by a major attack by the Royal Air Force with a subsequent firestorm . Since the attack was largely carried out on the densely populated city center, 11,500 people died. Around 66,000 were left homeless.

A total of around 99% of the old and inner city was destroyed, 78% of the building structure fell victim to the bombing. The air raid on Darmstadt claimed, as a percentage of the total population, after the air raid on Pforzheim, the second highest number of victims of all air raids on German cities in World War II . At the end of the war, the city, which was almost entirely in ruins, had a total of 12,300 victims.

Several months passed in the heavily destroyed city until National Socialism and the war came to an end when the city was occupied by the US 4th Armored Division on March 25, 1945.

Post War and Reconstruction

After the occupation of Darmstadt, Ludwig Metzger ( SPD ) was appointed Lord Mayor. In 1946 it was not Darmstadt, but the much larger Wiesbaden that became the capital of the newly founded state of Hesse .

During the reconstruction of the city, the large historical buildings such as the castle, town hall, town church and state museum were rebuilt. The old town got a new street layout. The original, mostly very small-scale parcelling has been largely abandoned. The residential buildings were given a new layout, which did not meet with approval from everyone in the population. The north-eastern old town was also redesigned with extensions to the university. The new buildings were erected in the rather unadorned functional forms of the time. The large-scale urban planning was based on the idea of Peter Grund, from 1947 head of the Darmstadt city administration, the system of "main streets as an organism". Later, completely intact old buildings had to be z. B. in the Martinsviertel give way, which seems incomprehensible against the background of the enormous war damage.

In 1947/48 the Zionist Jewish Vocational School Masada had its place in the city.

The old district court , built in 1905 and destroyed in the war , has been partially reconstructed.

The plane crash a Republic F-84 occurred 1,952th

The regenerative ruins of the old state theater were given up as a theater and replaced in 1972 by a new theater building on Wilhelminenplatz instead of the Ducal New Palace . The old palace on Luisenplatz , which had been completely destroyed in its essential substance , was not rebuilt either. After controversial debates among the population, the “ Luisencenter ” shopping center was built here in 1977 . At its inauguration, tomatoes and eggs flew. Only the reconstruction of the old pedagogue by 1984 represented a kind of turning point in this context, which only happened under the massive pressure of a citizens' initiative. At that point, most of what could have been rebuilt had been sacrificed to a largely modern cityscape. In 1986 the Darmstädter Tagblatt ceased its publication, it was until then the third oldest German daily newspaper.

Recent past

In 1988 the new synagogue was inaugurated, so that today there is an active Jewish community again. Darmstadt is still the only city in Germany that has donated a new synagogue as a gesture of reconciliation for the Jewish community.

Due to the large number of national and international research institutions, Darmstadt was awarded the designation " Science City " by the Hessian Ministry of the Interior in August 1997 .

On September 23, 2008, the city received the title “ Place of Diversity ” awarded by the federal government .

Darmstadt regents

Landgrave of Hesse-Darmstadt (1568–1806)

| 1568-1596 | George I. |

| 1596-1626 | Ludwig V. |

| 1626-1661 | George II |

| 1661-1678 | Louis VI. |

| 1678 | Louis VII |

| 1678-1739 | Ernst Ludwig |

| 1739-1768 | Louis VIII |

| 1768-1790 | Louis IX |

| 1790-1806 | Ludwig X. (from 1806 as Grand Duke Ludwig I) |

Grand Dukes of Hesse (1806-1918)

| 1806-1830 | Ludwig I. (formerly Landgrave Ludwig X.) |

| 1830-1848 | Ludwig II. |

| 1848-1877 | Ludwig III. |

| 1877-1892 | Ludwig IV. |

| 1892-1918 | Ernst Ludwig |

Theses, legends and attempts to explain the origin of the name Darmstadt

The unexplained and sometimes perceived as unflattering city name has led to different attempts at explanation, etymological interpretations and legends over the centuries.

Wildhübner Darimund

Since around the middle of the 19th century, the thesis of Wildhübner Darimund as the namesake of the city developed. The basis is the oldest documented spelling “Darmundestat” from the 11th century, which is interpreted as the “place of Darimund”. This thesis, which is still the most popular to this day, has some difficulties. For example, it is constantly asserted that Darimund was a wild booger of the Dreieich wilderness. The Wildbann Dreieich did not come into being until the middle of the 10th century, while the foundation of Darmstadt today is around the 8th / 9th century. Dated century. In addition, it is unlikely that a simple royal official should have given a settlement his name. This was only common with manors, which at that time and place can be recognized by the ending -heim , settlements with the ending -stat were named more according to their subject matter . Also the name Darimund was probably rather rare among the Franks. It is probably a variant of Thorismund, a name that has been passed down for a Visigoth king .

Settlement on the paved passage

This thesis derives the syllables dar from the Indo-European tar , which denotes a passage, mouth from Munt for protection and stat for place. Darmundestat would therefore be the "site at the fortified passage". Since one can assume that Darmstadt was an outpost of Frankfurt for protection against the Alemanni, this would be a fitting name, since Darmstadt was on one of the most important roads that led from the south (the Alemannic area) to Frankfurt.

Trajan city

Probably the oldest attempt to derive the name Darmstadt tries to identify the Roman Emperor Trajan as the namesake. The origin would have been a to this day unidentified Roman fortification with the name "Munimentum Traiani", which should have existed around 360 AD in the area on the right bank of the Rhine, as Ammianus Marcellinus reports. From Trajani Munimentum one derived from Tramunimentum and Tramundestat Darmundestat. Since it is assumed today that Darmstadt was founded by the Franks, this thesis has gone out of fashion.

Darmbach

The most popular explanation until the middle of the 19th century derived the name Darmstadt from the Darmbach , the small river that used to flow over the Darmstadt market square. Darmundstat would therefore mean: where the gut (brook) opens. However, since it has been proven that the brook was given this name in the 18th century at the earliest, this thesis is hardly tenable today.

Dambstadt

This thesis derives the name from the spelling Dambstadt, which is proven for the early modern period. This should be derived from the Old High German tamo (deer), which could allude to the abundance of forests and game in the Darmstadt area. However, this thesis causes difficulties on the one hand because the oldest known spelling Darmundestat already has the "r" in the first syllable (and therefore hardly derives from tamo) and on the other hand because it does not explain the syllable "munde".

Site on the Moorbach

An etymological attempt to identify the Darmbach as the patron saint derives “darm” as the older name for “moor”. The second syllable “unde” would correspond to the Old High German unda and mean “wave” or “wave”. According to this, Darm-Unda-Stat would then be a “settlement near the Moorbach”, which would probably have aptly described today's Darmbach in Franconian times.

Eichenberg

The first syllable dar is derived from the old Cymric dar for oak and mouth from the pre-Germanic mont for mountain. The original settlement was to the east of today's Darmstadt Castle on a small hill. In some village centers there were also old, cultically venerated trees, mainly old oaks. This is how you could explain the name "Eichenberg", although it looks very constructed.

Darmunda

This (surely unhistorical) legend tells of the count's daughter Darmunda, who, to the displeasure of her father, fell in love with a poor knight. She and her knight fled to a hut in the woods. Darmunda later reconciled with her father, and the count built a hunting lodge where the Darmstadt residential palace is today. Legend has it that Darmunda's hut was the “peasant house” destroyed in the air raid in 1944, a mysterious building in the north facade of the castle, the exact purpose of which has not been clarified (but was more likely a remnant of the previous building of today's castle).

Armstadt

Another legend of this kind, probably the most widespread, is a story that the court librarian Philipp AF Walther described in 1857 with the word “sweet”. Accordingly, Darmstadt was originally called Armstadt and (Groß-) Umstadt was called Dummstadt. And because some didn't want to be poor and others didn't want to be stupid, the D was swapped so that Armstadt became Darmstadt and Dummstadt Umstadt. This legend does not explain why the people of Darmstadt did not worry that their city was now named after a digestive organ.

See also

literature

- Friedrich Battenberg a. a .: Darmstadt's story. Prince's residence and township over the centuries . Eduard Roether Verlag, Darmstadt 1984, ISBN 3-7929-0110-2 .

- Monument topography Federal Republic of Germany: Cultural monuments in Hesse: City of Darmstadt . Vieweg, Braunschweig 1994, contains around 70 pages of an introduction to Darmstadt's history, ISBN 3-528-06249-5 .

- Klaus Schmidt: Die Brandnacht - Documents from the destruction of Darmstadt on September 11, 1944 , Verlag HL Schlapp, Darmstadt 2003 (first edition Reba-Verlag Darmstadt 1964), can be ordered from Libri, Georg Lichtenbrinck & Co KG through bookshops or via the Internet. ISBN 3-87704-053-5 .

- Klaus Honold: Darmstadt in a firestorm - the destruction on September 11, 1944 . Wartberg Verlag, Gudensberg-Gleichen 2004, ISBN 3-8313-1466-7 .

- Manfred Knodt : The regents of Hessen-Darmstadt . Verlag HL Schlapp, Darmstadt 1976, ISBN 3-87704-004-7 .

- Hartwig Beseler, Niels Gutschow: War fates of German architecture - losses, damage, reconstruction. Vol. 2. South. Karl Wachholtz, Neumünster 1988, pp. 772-797, ISBN 3-926642-22-X .

- Fabian Ortkamp: Construction planning in Darmstadt 1944–1949 . Hessisches Wirtschaftsarchiv 2017, ISBN 978-3-9816089-3-9 .

- LG Darmstadt, July 14, 1950 . In: Justice and Nazi crimes . Collection of German criminal judgments for Nazi homicidal crimes 1945–1966, Vol. XXII, edited by Irene Sagel-Grande, Adelheid L. Rüter-Ehlermann, HH Fuchs, CF Rüter . Amsterdam: University Press, 1981, No. 611, pp. 657-682. Arrest of 12 Jews living in 'mixed marriages' for void or fictitious reasons. Nine of those arrested were killed in a concentration camp.

Individual evidence

- ^ Darmstadt's beginnings from the 11th to the 16th century. (PDF; 290 kB) City of Darmstadt, accessed in April 2019 .

- ^ Hexenwahn in Darmstadt - The case of Wolf Weber and Anne Dreieicher ( Memento from August 24, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Mona Sauer: Parade House. In: darmstadt-stadtlexikon.de. Retrieved July 24, 2020 .

- ↑ NN: 40. Hessen-Darmstadt . In: Joint deputation of the associations for agriculture and polytechnics in Baiern (ed.): Monthly newspaper for building and land beautification . Volume 3 (1822), p. 43.

- ↑ Law on the Conditions of the Class Lords and Noble Court Lords of August 7, 1848 . In: Grand Duke of Hesse (ed.): Grand Ducal Hessian Government Gazette. 1848 no. 40 , p. 237–241 ( online at the information system of the Hessian state parliament [PDF; 42,9 MB ]).

- ↑ Karl Knapp: "Griesheim: from the Stone Age settlement to the living city", Bassenauer, Griesheim 1991, ISBN not available, p. 327, lines 13-17

- ↑ Darmstadt's history - royal residence and township through the centuries, section 3: From the honest man to the catastrophe of the firestorm , Eckhart G. Franz, Eduard Roether Verlag, Darmstadt 1980, p. 470, ISBN 3-7929-0110-2

- ↑ RAF mission report to 11./12. September 1944 ( Memento from March 31, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The fate of war in German architecture - losses, damage, reconstruction. Vol. 2. South. Karl Wachholtz, Neumünster 1988, p. 787, ISBN 3-926642-22-X

- ↑ The fate of war in German architecture - losses, damage, reconstruction. Vol. 2. South. Karl Wachholtz, Neumünster 1988, p. 783 & p. 784, ISBN 3-926642-22-X

- ↑ The Fate of German Architecture at War - Loss, Damage, Reconstruction. Vol. 2. South. Karl Wachholtz, Neumünster 1988, p. 772 - p. 797, ISBN 3-926642-22-X

- ^ Darmstadt's history. Prince's residence and township over the centuries . Eduard Roether Verlag, Darmstadt 1984, ISBN 3-7929-0110-2

- ↑ Walther, Dr. Philipp AF, "Der Name der Stadt" in Deppert, Fritz (Ed.), Darmstädter Geschichte (n), Darmstadt 1980, p. 17

- ^ "Darimund", the mythical founder of Darmstadt ( Memento from December 15, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b "Darmstadt around 900", Darmstädter Echo of June 13, 2005 (PDF; 184 kB)

- ↑ Darmstadt's history - royal residence and citizen town in the course of the centuries, Darmstadt 1980, pp. 20ff., ISBN 3-7929-0110-2

- ↑ Deppert, Fritz (ed.), Darmstädter Geschichte (n), Darmstadt 1980, p. 22.

- ↑ Deppert, Fritz (ed.), Darmstädter Geschichte (n), Darmstadt 1980, p. 22.

- ↑ Deppert, Fritz (ed.), Darmstädter Geschichte (n), Darmstadt 1980, p. 23ff.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, 17,1,11

- ↑ Walther, Dr. Philipp AF, the Darmstadt antiquarian. Historical and moral images from Darmstadt's bygone times, Darmstadt 1857

- ↑ Darmstadt's History - Princely Residence and Citizens' Town through the Centuries, Darmstadt 1980, p. 20, ISBN 3-7929-0110-2

- ↑ Haupt, Georg, Die Bau- und Kunstdenkmäler der Stadt Darmstadt, Darmstadt 1952

- ↑ Sabais, Heinz Winfried, Darmstädter Views, Speeches and Essays, Darmstadt 1972, p. 34.

- ^ Heinrich Tischner: Darmstadt. Settlement names between the Rhine, Main, Neckar and Itter. Accessed April 2019.

- ↑ Darmstädter Echo of December 11, 2002, Nomen est Omen or - how did Darmstadt get its name? ( Page no longer available , search in web archives )

- ↑ Nodnagel, August, Darmundestadt, in Deppert, Fritz (ed.), Darmstädter Geschichte (n), Darmstadt 1980, pp. 25f

- ↑ Walther, Dr. Philipp AF, the Darmstadt antiquarian. Historical and moral images from Darmstadt's bygone times, Darmstadt 1857

Web links

- The city of Darmstadt's website

- Darmstädter Echo from April 9, 2005, Old Town Museum Hinkelsturm: Graphics by Christian Häussler from Breuberg - From Darmundestat to Darmstadt

- Color panels on the development of the city of Darmstadt from 900 to 1450 AD with comments by city archivist Dr. Peter Engels

- Darimund, the mythical founder of Darmstadt

- Deutsche Fotothek : "Geometric Plan of the Grand Ducal Residence City of Darmstadt" from 1831 (click on the magnifying glass symbol under the preview image to enlarge)

- War and war memorials in Darmstadt at sites-of-memory.de