Karl May's humoresques and historical stories

Karl May's humoresques and historical narratives are shorter texts from Karl May's early work . May wrote a number of historical stories about the historical personality Leopold I. von Anhalt-Dessau , known as "the old Dessauer", as a military humoresque .

Emergence

Until Karl May found his profession as an author of travel stories, he tried his hand at various directions of entertainment literature in his early work. These included u. a. Humoresque and historical stories. The humorous texts formed the contrast to May's serious Erzgebirge village stories , which also originate from this creative period.

The humoresques in general

Karl May's life was filled with misery, misfortunes and catastrophes. He later described himself as a favorite child of need, worry, and grief . Nevertheless, he was always in the mood for jokes, interspersed his works with amusing elements and was one of the few successful German-speaking humorists of the 19th century. According to Michael Zaremba , the "humorous energy [...] was fed by massive problems of repression related to his past life and his character". May tried to overcome the bad reality with humor and found it healing. Due to the autobiographical relevance of these texts, May's claim that his subjects came from real life and that everything was experienced is correct, as he merely reversed the actual circumstances. He portrayed his flaws and character weaknesses in his youth as foolish figures that he exposed to laughter. May also found inspiration in the carnival hustle and bustle of Batzendorf, a fictional community played by the citizens of his homeland.

According to his own statements, May had already published humoresques in the 1860s. Around 1864 May tried a humorous stage play: The Slipper Mill. Posse with singing and dancing in eight pictures. It remained unfinished, but motifs from it can be found in several of his works: u. a. in The Three Field Marshals , Goat or Bock and Der Scheerenschleifer . During May's second imprisonment (1865–1868) he put on a list of over a hundred titles and subjects . According to this repertory C. May he planned the cycle In the old nest. From the life of small cities . Some titles have been demonstrably implemented ( Im Seegerkasten , Im Wasserständer , the unfinished In den Eier ), others are reminiscent of published humoresques. Although research dates the origin of some of the humoresques to 1868–1870 (then the third period of imprisonment followed: 1870–1874), no story has been published before 1874. The oldest known humoresque appeared in 1875.

May wrote historical stories as military humor about the historical personalities Leopold I von Anhalt-Dessau and Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher . From 1879 no new humoresques appeared without a historical background. Instead, most of the Dessauer stories followed until 1883.

The historical stories in general

At times Mays reports were sought on historical figures, especially if it is a novella extended anecdotes acted. For example, B. the figure of the old Dessauer material for many writers. The combination of military and wit was particularly popular in the German Reich . Such stories were expected by publishers and readers of popular family magazines, and May had started to watch the literary market early on. So from the beginning he tried to put a historical hook on many of the stories in order to attract particular interest from his readership. According to the C. May repertory , a project on Prussian or German history was already being planned.

The Rose von Ernstthal (1874 or 1875) is the oldest known publication of a May story. It belongs to both the historical tales and the Erzgebirge village stories. However, it is shaped less by the village and more by the small town and soldier milieu and shows a high degree of similarity with the subsequent stories about the old Dessauer, who is already mentioned in it. May had picked up and varied many of the plot elements of this work in later stories.

May resorted to both internal and external European history and personalities, about which he obtained information through source studies in relevant literature and in lexicons , and mixed his stories with adventurous plot or the criminalistic scheme . In 1879, Three carde monte May's first short story for Deutscher Hausschatz appeared in words and pictures , which was to become its main publication for many years. All of the following historical stories without Dessauer reference also appeared in it, before May published almost only travel stories there from 1883. The work on these and the workload of the colportage novels led to the end of the early work.

The Dessauer stories in particular

Leopold I, known as "the old Dessauer" ( 1676 - 1747 ) was Prince of Anhalt-Dessau , the first important Prussian army reformer and one of the most popular Prussian generals. No other personality has fascinated May so deeply and continuously. In his time, the figure of Leopold I was already distorted anecdotally and the literature colored accordingly, so that May's view of the negative sides of this person was clouded and glorified. The anecdotes identified him as a strict and difficult sovereign, but his humorous nature made him popular with his soldiers and the people. This made him sympathetic to May; he thought it was particularly popular and unspoilt. In addition, May had found the punishment of his former misconduct too harsh and wanted to take revenge. By letting Leopold I and his troops, who had once defeated the Saxon military, triumph over the Saxons in the first stories ( Die Rose von Ernstthal and Unter den Werbern ), he was able to continue his campaign of revenge against the Saxon police and justice. Recurring characters appear in May's texts that reflect his father Heinrich August May, about whom he later wrote that he was a person with two souls. One soul infinitely soft, the other tyrannical. The ambivalent father image can also be seen in the portrayal of the prince.

After Leopold I had already been mentioned in May's oldest story, he himself was the focus of one of the oldest known publications of a humoresque: A Little Piece from Old Dessauer (1875). The prince was particularly present on the 200th anniversary of his birthday the following year. May traveled to Dessau to study and had the opportunity to study all the literature available at the time about the prince. Under the impression of this trip, Unter den Werbern was created and seven more stories about the old Dessauer were to follow over the next few years. May's literary development is evident in the later stories, as they show an interweaving of several storylines as well as better character drawing and depiction of the situation comedy. May's sources included a. Karl August Varnhagen von Enses “Biographical Monuments” and Franz Carion's novel “The Old Dessauer”.

Although Pandur and Grenadier (1883) formed the last Dessauer story, May did not let go of this topic: in 1892 he informed his publisher Friedrich Ernst Fehsenfeld that he was planning a farce about the prince. To this end, he undertook study trips to Dessau in 1894 and 1898. During the last trip he came to Gartow and surroundings , scenes of action of several Dessauer stories where May by unusually high gratuities noticed and was therefore asked by the police to establish the identity under arrest. In the literature it was assumed that this event shocked May so much that he no longer carried out his work. However, there are indications that he did not take the incident that seriously, but that lack of time, the subsequent trip to the Orient and the turn to his later work prevented the implementation.

content

Basics of humoresques

Almost all humoresques take place in Germany. In the texts without historical reference, the milieu and dialect refer to the Ore Mountains as the place of action, where the story often takes place in two neighboring towns. The readership is often put into a storytelling group in which one of the participants tells his story. Almost all humoresques are more or less about the fact that two lovers , whose connection are opposed to various reasons, find each other. In the humoresque without a historical background, the will of the father or both parents is usually against it, whereby it is less about the status differences of the lovers than more about the reputation of the parents: For example, the rejected son-in-law is in connection with the competitor of the father or a desired one Son-in-law should enrich the family. Often the girl's parents get into trouble or are already in it. The connection usually comes about because they either give in to the threat of being exposed to ridicule or are indebted to their savior. The conflict can be resolved through the hero's prudence as well as by chance. In the military humor, political or military reasons speak against a coming together of the connection and here the old man from Dessauer usually provides a remedy.

May deals with serious issues such as poverty, vice, the arbitrariness of the powerful and the coming together of lovers with smiles and a wink. With the help of the pranks the oppressors are disarmed and the oppressed get their rights. This is not about revenge, but the punishment has a liberating effect. Thus, many texts are based on a moral, e.g. B. Criticism of ghosts and superstitions , of alcoholism or of the Bismarck cult. Since the powerful experience mishaps and the old Dessauer is distorted to the national father close to the people, one can speak of an anti-bourgeois affect, according to Martin Lowsky .

Specifics of the Dessauer stories

Four motifs appear regularly in the stories about the Old Dessauer: anecdotes about the prince, the masquerade, the pressing and the above-mentioned bringing together of lovers. May uses a fixed, relatively limited plot repertoire, the main features of which mostly come from his templates.

May describes Leopold I as “a huge brute, as a drunkard and gambler, as an unscrupulous recruit catcher. He booms and curses and also hits with the stick ”. But he is an ambivalent figure; he takes back wrong and makes amends for damage; B. those of his officials, of whose evil machinations he knows nothing. “Angry and tough, soft and cozy, bossy and affable, desolate and yet helpful, that's all at the same time,” summarizes Hermann Wohlgschaft . Even despotic methods of rule, actually expressions of absolutist power, appear only as a result of his rudeness and charisma of personality. The prince therefore appears as a lovable and good figure, because he himself harbors foolishness, can laugh at himself, his acts of violence are outshone by comedy and what he does - often by chance - ultimately turns out to be an advantage. Consent to marriage and the transfer of the management of a property are given by the prince as a reward, while the negative characters are punished with forced recruitment. The preference for the Dessau March , to the tune of which Leopold I sang all the songs, and his dubious reading and writing skills are mentioned again and again. “This is by no means done with the intention of making him look ridiculous; Rather, May wants to emphasize the original, quirky features of the sovereign, who should by no means be portrayed as a blasé nobleman, but on the contrary as a simple, 'folksy' man, "says Christoph F. Lorenz . Lowsky states that the disguises remove class differences (anti-feudalist impulse), that “rough-nosedness eventually turns into a culture satire ” and sees through social criticism when May gives a picture of everyday life in Dessau Castle.

In addition to Leopold I, May lets other historical personalities appear. From his family, May introduces the bourgeois wife of Prince Anna Luise , called Anneliese, daughter Luise von Anhalt-Dessau (1709–1732) Luise and her later husband Viktor II. Friedrich von Anhalt-Bernburg and son Moritz . He also introduces the readers to Johann Georg von Raumer and Soldier King Friedrich I Wilhelm - initially Crown Prince. On the side of the opponents are the Swedish king Karl XII. and Carl Piper , the Duke of Saxe-Merseburg and Count Johann Georg III. von Mansfeld , the Hanoverians Prince Friedrich Ludwig von Hanover and Andreas Gottlieb von Bernstorff and Franz von der Trenck . Other historical figures, especially Frederick the Great , are mentioned.

The locations and times as well as the historical background of the individual stories are given in the following table:

| title | Locations | Action time | Historical background | Opponent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The scissors grinder | Halberstadt , Dankerode , Allstädt | 1707 |

Great Northern War (1700–1721) Sequestration of the County of Mansfeld (1579–1780) |

Sweden , Mansfeld |

| A piece of old Dessau | Dessau, Wahlsdorf | possibly between 1720 a. 1730 |

a bailiff | |

| The plum thief | Dessau, Leinefeld | 1724 | Jesuits , a bailiff | |

| A Prince-Marshal as a baker | Dessau, Lüchow , Wustrow , Lenzen | 1726 | Friedrich Ludwig of Hanover | |

| Prince and Leiermann | Prezelle , Ziemendorf | 1741 | First Silesian War (1740–1742) | Hanoverian advertisers |

| The three field marshals | Lenzen, Gartow | 1741 | ||

| Pandur and Grenadier | Studenetz , Humpoletz , Chrudim | 1742 | Franz von der Trenck | |

| The Amsenhandler | Dessau, Gartow, Lenzen | 1743 | Hanoverian advertisers | |

| Among the advertisers | Dessau, Beyersdorf , Bitterfeld | 1745 | Second Silesian War (1744–1745) | Saxon advertisers |

The Old Dessauer goes into every story incognito or in the often eponymous cladding (eg. As a merchant ants , baker , beggars , organ grinders , craft bursche , miller or knife-grinder ) among the people, to spy, " Lange guy " for his army to catch or learn what to think of him and his politics. In doing so, he gets into strange situations due to his human weaknesses (e.g. appetite) or accidents. Involuntary unmasking also forms part of the comedy. Not only the prince, but also others, both fictional and historical, use the incognito.

Since in Leopold I's times - unlike May's - the soldier's status had a bad reputation, young, strong men and especially "tall guys" were recruited as soldiers through cunning or violence. This pressing took place not only in their own country, but also in neighboring countries. The Wendland , in which four of the stories take place, was sparsely populated, had a weak military presence and a long, difficult-to-guard border between Hanover and Prussia: an ideal place to squeeze recruits across the border. The prince hunts the Hanoverian “soul sellers”, but also goes over to the press himself. The advertiser , whether Hanoverian, Saxon, Prussian or Anhalt, is criticized by May. Although the stories in the military milieu and z. Sometimes playing during some wars, they stay away from the chaos of battle. The Prince's drill and the atrocities of the Trencks are mentioned, but only harmless scenes are described.

Historical personalities and backgrounds of other stories

The rose of Ernstthal occupies a special position within his historical narratives , as it belongs to the Erzgebirge village stories as well as being very similar to the Dessauer stories. The setting is May's birthplace at the time of the Second Silesian War (1744–1745). A Prussian officer, godson of the old Dessauer and lover of the title character, tracks down a traitor who collaborates with Saxon advertisers.

Anecdotes about the pranks and riding skills of the young Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher in Stolp after 1770 worked through May in the military humorous hussar pranks . The preparation for Blücher's crossing of the Rhine during the Wars of Liberation (1813–1815) is dealt with in Die Kriegskasse . Although May depicts anti-French and pro-German tendencies in relation to military events, the story remains free from nationalist prejudices.

The lyrics Ein Self-man and Three carde monte are actually adventure stories set in the United States and spun around two historical figures. The respective narrator meets the young Abraham Lincoln several times and confronts the cardsharp and supposed villain Canada-Bill with him. Both stories have in common the first meeting of the heroes when Lincoln is practicing a speech in the forest.

May's South Africa story The Boer van het Roer - revision of the shorter version The Africander for the travel story - takes place shortly before the decisive battle between the Zulu chiefs Panda and Dingaan in 1840. On the side of the pandas are the heroes and the (actually deceased) Boer leader Pieter Uys . It is remarkable that, as in the previous story, May, contrary to the prejudices of his time , lets a white hero marry a colored woman.

Almost all the characters in the crime novella Ein Fürst des Schwindels - revision of the shorter version Aqua benedetta - are historical. The hero's opponent is the Count of Saint Germain , known as an alchemist , secret agent and impostor , who first lived in Versailles in the presence of Madame de Pompadour and King Louis XV. occurs. The plot then changes to Haag , where Giacomo Casanova also opposes the Count, and ends with his death in 1780 (actually 1784) at Karl von Hessen-Kassel in Eckernförde .

In the novella Robert Surcouf , the eponymous hero first meets Napoléon Bonaparte during the French Revolution in Toulon . In the Indian Ocean he fought England by capturing its ships and thereby became a naval hero. After the revolution, Surcouf returned to France, where he met Napoléon again in Paris . In a side episode, this meeting was preceded by the audience of Robert Fulton in 1801, who asked unsuccessfully for support for the development of the steamship .

humor

May uses humor to typify the characters, in monologues and dialogues as well as situation comedy. May's comedy includes the characters' linguistic peculiarities, such as confusion of language, constantly repeated phrases or the repeated but never-ending story. Just as often he uses elements of the carnival such as swearing, the apparent humiliation of the high and the exaltation of the low, caricature of dignitaries and the motif of the masquerade. In addition, there is the game with foreign words, unusual animal descriptions and the language situation with the symmetry principle, in which identical facts are named and assessed differently. May does not limit himself to a cheerful representation, but also uses the comedy to solve the tension.

The humoresques without a historical background are “more convincing from the humorous side” than the Dessauer stories. Overall, according to Zaremba, May's humor turns out to be “more witty and popular than in earlier phases of his work” in his later works.

Truthfulness

As an example, it was shown that May knew how to accurately and realistically reproduce the small-town milieu in the humoresques without historical reference.

Many of the anecdotes used by May about the old Dessauer, u. a. that he wanted to move unrecognized in the country is historically guaranteed. The facts about the person are also shown correctly with a few exceptions. In the case of secondary persons, general living conditions and localities, however, May becomes imprecise or provides unhistorical information. May wants to convey historicity to the reader, but transfers the status of the 19th century into his texts without adapting this for the actual plot time. This leads to people having wrong titles, performing functions that have not (yet) been achieved or not being on site at the relevant time and historical circumstances such as B. Boundaries are ignored. For example, the negative image that May paints of the Jesuits did not correspond to the reality during the action time, but presumably reflects the Kulturkampf that led to their ban in Prussia. The landscapes and places also remain pale and are z. T cannot be located. The Dessauer stories hardly suffer from these weaknesses, however, since they do not form more than the background.

In the other historical narratives, the truth content is different: May has taken historical facts about Blücher from his sources. Both the Bellingshausen - Hussars , and the Lutzow Freikorps in the Blücher stories has given it. There are a few historical references in the two Wild West stories, but apart from that they have little in common with the actual history: The Canada Bill was - apart from cheating - just as little a villain as Abraham Lincoln was a significant adventurer. His fictional speeches are similar to historical ones, but his presence during an oil fire is an anachronism . In the South Africa stories, on the other hand, the historical and geographical background and the depiction of historical personalities are largely correct, in some cases even down to the last detail. The anachronisms occurring here arise from the fact that May further adorns the end of Dingaan's rule with historical details of two earlier battles. This led to the appearance of the already deceased Pieter Uys. The Saint-Germain stories are also relatively close to true history. However, the actual periods do not quite match. Robert Surcouf and his activities, the situation in France and generally in Europe between 1793 and 1804, as well as the piracy of that time and its historical framework, was correctly presented by May. Of Surcouf's encounters with Napoléon, only the reward is historically documented.

In view of the lack of authenticity in places - apart from poetic freedom - it must be remembered that May at that time was “constantly following the subsistence level (wrote)” and was therefore under high production pressure. In addition, his research options were limited.

militarism

Many of the works dealt with here are distinguished by the soldiers' milieu and contradict May's other peace efforts. In doing so, he vacillates between anti-militaristic remarks and the joy of military humor, the compatibility of which is controversial in May research.

There are different views on May's attitude to the military during his early work: Gerhard Klußmeier warns against filtering anti-militarist remarks from the Dessauer stories, because he sees a "sympathy and ultimately admiration for the soldier class at that time" in May, von der he only turned away later. The soldier's status was very respected at the time and therefore May felt his retirement in 1862 was a "personal shortcoming". In May's texts from this period, sympathy belongs to the officers, provided they are on the right side, while the civilians are often portrayed as clumsy and can even become the object of rough jokes by the officers. The presentation of dashing, impeccable officers was typical of the genre and corresponded to the taste of the time. There is also a commercial aspect to consider when May "takes into account the expectations of his audience as well as the requirements of popular family magazines by [...] choosing a military figure as a hero". According to Lorenz, May was “a child of his time, with a naive joy in successful military coups”, but without a “particularly pronounced militaristic attitude”. During his third imprisonment, May was imprisoned in Waldheim prison and Hainer Plaul attributes an aversion to the Saxon military to the guards there. Herbert Meier even sees a general aversion to the soldier's status and officers, which Klaus Walther attributes to the fact that May's father exercised military orders with his son. Hartmut Kühne points out that the negative figures are almost regularly punished with recruitment, and deduced from this that "the soldier's trade [...] was a somewhat desirable existence in May's eyes". May mentions the negative influence of the military on private life, but he conceals the horror of everyday soldiers' life, even though critical literature was already available. Advertising is generally portrayed negatively, but Axel Kahrs sees the Dessauer stories as a trivialization of the press into an "adventure with fun parts". Especially Leopold I, who assesses the usefulness of soldiers only according to body size and musculature, would, according to Stephan Kraus & Hartmut Wörner , have been “suitable for the personification of an anti-militarist point of view”.

In the early work there are hardly any clear tendencies towards May's later pacifism . Open criticism of the Prussian military system in the 1870s / 80s was unthinkable for a convicted person. Criticism can only be read between the lines. An example of an early emphasis on his love of peace can be found in his Geographische Sermons (1875/76): Reminds but grad '(the word "field") of the greatest and ugliest contrast of love, which its victims under the roaring stomping of horses and the roaring thunder of cannons the “battlefield” in “death's bloody roses”. There are clear indications of pacifism in the travel stories. May criticizes the Prussian military system under the guise of the North American military, who have clear characteristics of the German authoritarian state. It was only in his later work that May decidedly advocated pacifism and wrote, for example, B. with Und Friede auf Erden (1904) against public opinion.

criticism

By revising older texts, May perfected his works and a progression of his writing skills can already be seen in the first few years. Nevertheless, the early work - with a few exceptions - does not stand up to comparison with later works. The literary novice is recognizable in the texts.

Wohlgschaft finds the humoresques without historical reference to be written as "very fluid and amusing, very funny and exciting"; According to Eckehard Koch, they are "lovingly painted in detail" and, according to Plaul, sometimes take on "a good medium level". Wohlgschaft Im Wollteufel is one of May's best humoresques . These humoresques are more successful in form and content than the Dessauer stories. The literary value of the Dessauer stories is controversial in May research. Kühne describes the rose of Ernstthal as “written fluently and skilfully constructed” ”. In the story Die Kriegkasse, Lowsky found a clever technique of anticipation, but a failed arc of suspense. Meier sees the texts that May published in Frohe Stunden ( Die Kriegskasse , Aqua benedetta , Ein Self-man , Husarenstreich and Der Africander ) as "angular and woodcut-like narrated", since they are probably no more than sketches made under high pecuniary pressure . Later new versions ( Three carde monte. Der Boer van het Roer and Ein Fürst des Schwindels ) are, according to Meier and Siegfried Augustin, “qualitatively better, more solid, much broader in the narrative flow” and sometimes much more exciting. However, Three carde monte with a haphazard plot and undifferentiated drawing of people is noticeable negatively, says Claus Roxin . Regarding Der Boer van het Roer , Koch states, "You think you are not looking at an early story, but a travel adventure from May's 'more mature' time as a writer". According to Meier, Robert Surcouf is written vividly and excitingly and is considered one of the best historical novels.

It is particularly noteworthy that May treated colored people as equal people, contrary to the prejudices of his time.

Significance for later works

The narratives dealt with here are of great importance for the development of the literary work: As in other of his early works, the characters, plot elements and scenes are pre-formed in the humorous and historical narratives, which May later transferred to foreign countries in his colportage novels and travel stories worked out further. Many motifs such as the chase, eavesdropping, riding a wild horse, raising treasure, appearing as someone inferior and then proving to be an all-rounder can already be found in the historical stories. In addition, the “I ideal” of the travel stories, which is based on these motifs, is already taking on a solid form. Without the humoresques as preliminary studies, the bizarre figures of the later works such as B. Hobble-Frank and Heimdall Turnerstick inconceivable.

bibliography

These stories first appeared in entertainment newspapers and folk calendars , including those that May himself edited (e.g. Deutsches Familienblatt and Frohe Stunden ). Some texts appeared under the pseudonyms Emma Pollmer, Ernst von Linden or Karl Hohenthal. A number of the texts were z. T. reprinted several times. May also submitted works as original contributions that had already appeared elsewhere by simply changing the title, the author's statement, or both.

The following tables contain the current numbers of the volume and the story from Karl May's Gesammelte Werken (titles may differ here), the title of the corresponding reprint of the Karl May Society and the department and volume number of the historical-critical edition of Karl May's works (if already published).

Humoresques without historical reference

| title | year | Remarks | Karl May’s Collected Works |

Reprints of the Karl May Society |

Historical-critical edition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the Seegerkasten | 1875 | 84 , 14 | Among the advertisers | I.3 | |

| The carnival jesters | 1875 | First print in self-edited sheet | 72 , 03 | Old Firehand | I.3 |

| Fumigated | 1876 | 47 , 05 | Among the advertisers | I.3 | |

| On the nut trees | 1876 | First print in self-edited sheet | 47.12 | Old Firehand | I.3 |

| In the water stand | 1876 |

90 , 05 (47.07) |

Among the advertisers | I.3 | |

| In the wool devil | 1876 | First print in self-edited sheet | 47.06 | Celebrations at the domestic flock | I.3 |

| The fateful New Year's Eve | 1877 | 84.15 | Among the advertisers | I.3 | |

| The two night watchmen | 1877 | Variant of the fateful New Year's Eve |

47.09 | The forest king | I.3 |

| The Ducatennest | 1878 | Revision of Im Seegerkasten | 90.06 (47.13) |

Old Firehand | I.3 |

| The wrong excellencies | 1878 | 47.08 | Among the advertisers | I.3 | |

| The cursed goat | 1878 | 47.10 | Old Firehand | I.3 | |

| Goat or buck | 1878 | Variant of The Cursed Goat | 79 , 06 | I.3 | |

| The leaf thaler | 1878 | Redesign of Fumigated | 90.04 | Old Firehand | I.3 |

| The universal heirs | 1879 | 47.11 | The forest king | I.3 | |

| In the eggs | Fragment, estate | 90.09 | I.3 | ||

| [Otto Victor fragment] | Fragment, estate | 79.07 | I.3 |

Similar to these humoresques are the beginning and end of the crime novel Auf der See gefangen (1877/78), which draws on staff from the Otto Victor fragment and Ziege or Bock , as well as the Old Shatterhand pranks in the deleted chapter In the home of Krüger At (1894). These humoresques have the setting in common with the Erzgebirge village stories .

Stories about the old man from Dessauer

| title | year | Remarks | Karl May’s Collected Works |

Reprints of the Karl May Society |

Historical-critical edition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A piece of old Dessau | 1875 | First print in self-edited sheet | 84.12 | Old Firehand | |

| Among the advertisers | 1876 | First print in self-edited sheet | 42 , 07 | Among the advertisers | |

| The three field marshals | 1878 | 42.05 | Old Firehand | ||

| The plum thief | 1879 | Revision of A Piece of Old Dessau |

42.03 | The forest king | |

| The scissors grinder | 1880 | 42.01 | Old Firehand | ||

| Prince and Leiermann | 1881 | 42.04 | Among the advertisers | ||

| A Prince-Marshal as a baker | 1882 | 42.02 | Among the advertisers | ||

| The Amsenhandler | 1883 | 84.13 | Among the advertisers | ||

| Pandur and Grenadier | 1883 | 42.06 | Among the advertisers |

The subtitles mostly refer to an episode from the life of the (") old Dessauer (s) (") .

Further stories with historical personalities and backgrounds

| title | year | Remarks | Karl May’s Collected Works |

Reprints of the Karl May Society |

Historical-critical edition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The rose of Ernstthal | 1874 or 1875 |

Erzgebirge village history | 43 , 08 | Among the advertisers | |

| The war chest | 1877 | First print in self-edited sheet | 47.04 | Happy hours | |

| Aqua benedetta | 1877 | First print in self-edited sheet | 71 , 07 | Happy hours | |

| A self-man | 1877/78 | First print in self-edited sheet | 71.08 | Happy hours | I.8 |

| Hussar pranks | 1878 | Military humor, first print in self-edited sheet |

47.03 | Happy hours | |

| The Africander | 1878 | First print in self-edited sheet | 71.09 | Happy hours | I.8 |

| Three carde monte | 1879 | Motive variation from a self-man | ( Book version : 19 , chapters 1–3) |

Small treasure trove stories | |

| The Boer van het Roer | 1879 | Adaptation of Der Africander for travel narration |

( Book version : 23 , 02) |

Small treasure trove stories | |

| A prince of fraud | 1880 | Revision of Aqua benedetta | 48.01 | Small treasure trove stories | |

| Robert Surcouf | 1882 | 38 , 02 | Small treasure trove stories |

May's works also include historical novels or novels with historical references: The two Quitzow's last journeys (1876/77, end not by May), The Waldröschen (1882–84), The Love of the Uhlan (1883–85, with performances von Blücher and Napoléon), German Hearts - German Heroes (1885–88) and The Path to Happiness (1886–88).

Book editions

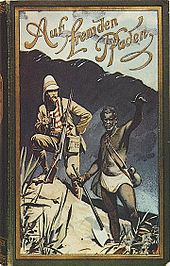

Reprints of the humoresque Die Fastnachtsnarren , Im Seegerkasten , Ein Stück vom alten Dessauer and Die Zwei Nachtwächter appeared in The Book of Entertainment (1879 or 1880), the book Fürst und Leiermann followed in 1884 and The Three Field Marshals became the 32nd volume in Bachem’s novellas in 1888 Collection added. May himself published Robert Surcouf under the title Ein Kaper as the first section of the book Die Rose von Kaïrwan (1893 or 1894), in which there is a loose reference to the third section, the travel story Eine Befreiung . Ein Self-man and Der Africander appeared under the titles In the Wild West and An Adventure in South Africa in the anthology Der Karawanenwürger (1894). Three carde monte appeared in book form through the integration into the text of Old Surehand II (1895), whereby May now also describes the death of the Canada Bill and reinterprets its anachronism by changing the frame narrative. In contrast to the previous version, Boer van het Roer is already a travel story , but May edited it when it was incorporated into the anthology Auf Fremd Pfaden (1897) in order to relocate the plot to his own lifetime. Those texts that were published by Verlag HG Münchmeyer were published in the anthology Humoresken und Erzählungen (1902) without May's authorization , with Der Amsenkauf the title of Ein Stücklein vom alten Dessauer .

literature

- Ulf Debelius: editorial report. In: Karl May: The Carnival Fools . Karl May's works, historical-critical edition for the Karl May Foundation, Volume I.3. Karl-May-Verlag, Bamberg / Radebeul 2010, ISBN 978-3-7802-2002-8 , pp. 421-507.

- Hans-Jürgen Düsing: Stories about history about the "Old Dessauer". In: Communications from the Karl May Society. No. 152/2007, pp. 18-33. ( Online version )

- Christian Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer" along with the two little-known humoresques A little piece of the old Dessauer and the Amsen dealer. Anhaltische Verlagsgesellschaft, Dessau 1991, ISBN 3-910192-02-5 .

- Axel Kahrs: "Hundsfott - Himmelhund - Papperlapapp - Pasta!" News from Karl May and the old Dessauer in Gartow. In: Communications from the Karl May Society. No. 97/1993, pp. 57-62. ( Online version )

- Gerhard Klußmeier, Kerstin Beck: "Seated in the hotel I lost the world ..." Karl May's trip to Gartow, Kapern, Lenzen, Lanz and Schnackenburg in 1898 ... Lumea Verlag, Lüchow 2012, ISBN 978-3-942400-02-2 .

- Bernhard Kosciuszko: The great Karl May figure lexicon. 3. Edition. Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-89602-244-X . ( Online version of the 2nd edition )

- Christoph F. Lorenz: sovereign and smuggler prince. A review treatise on Karl May's stories in the magazine “For all the world” (= “All-Germany”) in the years 1879 and 1880. In: Claus Roxin, Heinz Stolte, Hans Wollschläger (ed.): Yearbook of Karl-May -Gesellschaft 1981. Hansa-Verlag, Hamburg 1981, ISBN 3-920421-38-8 , pp. 360-374. ( karl-may-gesellschaft.de ).

- Herbert Meier: Introduction. In: Karl May. Smaller house treasure counts from 1878–1897. Reprint of the Karl May Society and the Pustet bookstore, Hamburg / Regensburg 1982, pp. 4–44. ( karl-may-gesellschaft.de ; PDF; 34.8 MB).

- Herbert Meier (Ed.): Karl May. Among the advertisers. Rare original texts. Volume 2. Reprint of the Karl May Society, Hamburg / Gelsenkirchen 1986. ( karl-may-gesellschaft.de ; PDF; 26.6 MB).

- Hainer Plaul: Illustrated Karl May Bibliography. With the participation of Gerhard Klußmeier . Saur, Munich / London / New York / Paris 1989, ISBN 3-598-07258-9 .

- Malte Ristau: Prince Leopold is no longer convincing today. A multi-layered look at the old Dessauer in Karl May. In: Jb-KMG. 2018, pp. 239–282.

- Gert Ueding (Ed.): Karl May Handbook. 2nd Edition. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2001, ISBN 3-8260-1813-3 .

- In the under bibliography mentioned reprints, further work items found.

Web links

- Digital reprints on the Karl May Society website

- List of entries for the individual humoresques in the Karl May Wiki

- Entry on Leopold I of Anhalt-Dessau in the Karl May Wiki

- 8 audios with Ilja Richter reads stories from old Dessau

Individual evidence

- ↑ Martin Lowsky: Karl May (Realien zur Literatur, Volume 231). J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung and Carl Ernst Poeschel Verlag, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-476-10231-9 , p. 38 ff.

- ↑ Heinz Stolte: Fools, Clowns and Harlequins. Comedy and humor with Karl May. In: Claus Roxin, Heinz Stolte, Hans Wollschläger (Eds.): Yearbook of the Karl May Society 1982. Hansa Verlag, Husum 1982, ISBN 3-920421-42-6 , p. 40– 59 (43). ( karl-may-gesellschaft.de ).

- ↑ Karl May: My life and striving. Volume I . Published by Friedrich Ernst Fehsenfeld, Freiburg i. Br. 1910, p. 8. ( karl-may-gesellschaft.de ; PDF; 16.9 MB)

- ↑ Stolte: Fools, Clowns and Harlequins. P. 45.

- ↑ Michael Zaremba: Structures of humor in Karl May. In: Claus Roxin, Helmut Schmiedt, Hans Wollschläger (ed.): Yearbook of the Karl May Society 1998. Hansa Verlag, Husum 1998, ISBN 3-920421-72-8 , Pp. 164-176 (164). ( karl-may-gesellschaft.de ).

- ↑ Zaremba: Structures of Humor. P. 175.

- ^ Hermann Wohlgschaft: Karl May - Life and Work . 3 volumes. Bücherhaus, Bargfeld 2005, ISBN 3-930713-93-4 , p. 363 ( karl-may-gesellschaft.de ( Memento of the original from November 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this note. 1st edition)

- ↑ Stolte: Fools, Clowns and Harlequins. P. 46f.

- ↑ Zaremba: Structures of Humor. P. 172.

- ↑ Wojciech Kunicki : Karl May's humoresque “The fateful New Year's Night”. Attempt at interpretation. In: Claus Roxin, Heinz Stolte, Hans Wollschläger (eds.): Yearbook of the Karl May Society 1988. Hansa Verlag, Husum 1988, ISBN 3-920421-54-X , pp. 248-267 (255).

- ↑ May: My life and pursuit. P. 113 ff.

- ↑ a b Debelius: editorial report. Pp. 425-427.

- ↑ Christoph F. Lorenz: Karl Mays "Die Pantoffelmühle". Posse with singing and dancing in eight pictures. In: Hartmut Kühne, Christoph F. Lorenz (eds.): Karl May and the music . Karl-May-Verlag, Bamberg / Radebeul 1999, ISBN 3-7802-0154-2 , pp. 222-241.

- ↑ Karl May: Old Shatterhand in the home . Karl-May-Verlag, Bamberg / Radebeul 1997, ISBN 3-7802-0079-1 , pp. 256-258, 277-279.

- ↑ Kunicki: Karl May's humoresque "The fateful New Year's Night". P. 248 f.

- ^ Debelius: editorial report. P. 500.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". P. 71.

- ↑ Erich Heinemann: Introduction. In: The Scheerenschleifer / The Both Shatters / Tui Fanua. Reprint of the Karl May Society, Hamburg 1977, p. 2.

- ^ Roland Schmid: Afterword. In: Karl May: The old Dessauer. Karl-May-Verlag, Bamberg 1968, p. 513.

- ↑ Kahrs: Hundsfott. P. 60.

- ↑ Ulrich Scheinhammer-Schmid: [Work article about] The Scheerenschleifer. In: Ueding: Karl May Handbook. P. 365.

- ↑ Eckehard Koch: The Gitano is a hunted dog. Karl May and the Gypsies. In: Claus Roxin, Heinz Stolte, Hans Wollschläger (eds.): Yearbook of the Karl May Society 1989. Hansa Verlag, Husum 1989, ISBN 3-920421-56-6 , pp. 178-229 (181). ( karl-may-gesellschaft.de ).

- ↑ May: Old Shatterhand in the home. Pp. 287-289.

- ↑ Sudhoff, Dieter, Mason, Hans-Dieter: Karl May Chronicle I . Karl-May-Verlag, Bamberg / Radebeul 2005, ISBN 3-7802-0170-4 , p. 187.

- ↑ Jürgen Hein: [Work article about] The rose of Ernstthal. In: Ueding, manual. Pp. 371-373.

- ^ Roland Schmid: Afterword by the editor. In: Karl May: The forest black . Karl-May-Verlag, Bamberg 1971, ISBN 3-7802-0044-9 , p. 466.

- ^ Benefit: Karl May - Life and Work. P. 357f.

- ^ Leopold I (Anhalt-Dessau). Version of April 3, 2013 at 12:56.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". P. 10.

- ^ Benefit: Karl May - Life and Work. P. 417.

- ↑ Kahrs: Hundsfott. P. 60f.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". P. 53.

- ^ Lorenz: sovereign and smuggler prince. P. 363.

- ↑ Christoph F. Lorenz: [article about] Among the advertisers. In: Meier: Among the advertisers. P. 122.

- ↑ May: Life and Striving. P. 158.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". P. 33.

- ↑ May: Life and Striving. P. 9.

- ^ Klaus Eggers: [article about] Among the advertisers. In: Ueding: Karl May Handbook. P. 348.

- ↑ a b Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer woman". P. 35 f.

- ^ Christian Heermann: Winnetou's blood brother. Karl May biography. Second, revised and expanded edition. Karl-May-Verlag, Bamberg / Radebeul 2012, ISBN 978-3-7802-0161-4 , p. 151.

- ↑ Scheinhammer-Schmid, The Scheerenschleifer. P. 365.

- ↑ Gerhard Klußmeier: Karl May and the "Old Dessauer". In: Meier: Among the advertisers. Pp. 9-12.

- ^ Letter of October 16, 1892. In: Karl May: Correspondence with Friedrich Ernst Fehsenfeld. First volume. 1891-1906. With letters from and to Felix Krais u. a. Karl-May-Verlag, Bamberg / Radebeul 2007, ISBN 978-3-7802-0091-4 , p. 93f.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". Pp. 63-70.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". P. 71.

- ↑ Klußmeier & Beck: "Seat in the hotel I lost the world ...". P. 7.

- ↑ Klußmeier & Beck: "Seat in the hotel I lost the world ...". P. 83 f.

- ↑ Engelbert Botschen: [article about] Smoked out. In: Meier: Among the advertisers. P. 184f.

- ↑ Hainer Plaul: Editor on time. About Karl May's stay and activity from May 1874 to December 1877. In: Claus Roxin, Heinz Stolte, Hans Wollschläger (eds.): Yearbook of the Karl May Society 1977. Hansa-Verlag, Hamburg 1977, ISBN 3-920421-32 -9 , pp. 114-217 (166).

- ^ Benefit: Karl May - Life and Work. P. 420.

- ^ Benefit: Karl May - Life and Work. P. 420f.

- ↑ Kunicki: "The fateful New Year's Eve". P. 253.

- ↑ Eckehard Koch: [article on] Die Fastnachtsnarren. In: Ueding: Karl May Handbook. P. 342.

- ↑ Plaul: Temporary editor. P. 194.

- ^ Lowsky: Karl May. P. 41.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". P. 46.

- ^ Lorenz: sovereign and smuggler prince. P. 364.

- ↑ Kahrs: Hundsfott. P. 57.

- ↑ Scheinhammer-Schmid, The Scheerenschleifer. P. 365.

- ↑ a b Wohlgschaft: Karl May - Life and Work. P. 417 f.

- ↑ Plaul: Temporary editor. P. 167.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". P. 55.

- ↑ Heinz Stolte: The popular writer Karl May . Karl-May-Verlag, Radebeul 1936, p. 137 f.

- ↑ Kahrs: Hundsfott. P. 60.

- ^ Lorenz: sovereign and smuggler prince. P. 366.

- ↑ Martin Lowsky: [article on] The three field marshals. In: Ueding. Karl May Handbook. P. 356.

- ^ Lowsky: Karl May. P. 41.

- ^ Dating from Düsing, Stories about History. Pp. 18-33.

- ^ Düsing: Stories about history. P. 21.

- ^ Agreement with Leinefelde uncertain

- ↑ The date mentioned in the text 1739 is not historically tenable.

- ^ Lorenz: sovereign and smuggler prince. P. 364f.

- ↑ Klußmeier: Karl May and the "Old Dessauer". P. 10.

- ↑ Kahrs: Hundsfott. P. 57.

- ↑ Kahrs: Hundsfott. P. 58f.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". P. 53.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". P. 50.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". P. 52f.

- ^ Herbert Meier: Foreword. In: Karl May. The forest king. Stories from the years 1879 and 1880. Reprint of the Karl May Society, Hamburg 1980, p. 15. ( Online version ( Memento of the original from February 24, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this note .; PDF; 27.3 MB)

- ^ Ruprecht Gammler: [article on] hussar pranks. In: Ueding, manual. P. 351f.

- ↑ Martin Lowsky: [article on] The war chest. In: Ueding, manual. P. 357f.

- ↑ Ekkehard Koch: The way to the "Kafferngrab". On the historical and contemporary background of Karl May's South Africa stories. In: Claus Roxin, Heinz Stolte, Hans Wollschläger (eds.): Yearbook of the Karl May Society 1981. Hansa Verlag, Hamburg 1981, ISBN 3-920421-38-8 , pp. 136-165 (152). ( karl-may-gesellschaft.de ).

- ↑ Koch: The way to the “Kafferngrab”. P. 151f.

- ↑ Martin Lowsky: [article on] A prince of swindles. In: Ueding, manual. P. 360f.

- ↑ Zaremba: Structures of Humor. P. 170f.

- ↑ Zaremba: Structures of Humor. P. 168.

- ↑ Christoph F Lorenz: The repeated history. The early novel ›Caught on the Sea‹ and its meaning in Karl May's work. In: Claus Roxin, Helmut Schmiedt, Hans Wollschläger (eds.): Yearbook of the Karl May Society 1994. Hansa Verlag, Husum 1994, ISBN 3-920421-67-1 , pp. 160-187 (182-185). ( karl-may-gesellschaft.de ).

- ↑ Kunicki: "The fateful New Year's Eve". P. 254.

- ↑ Zaremba: Structures of Humor. P. 175.

- ↑ Zaremba: Structures of Humor. P. 166.

- ↑ Kunicki: "The fateful New Year's Eve". P. 250.

- ↑ Plaul: Temporary editor. P. 166.

- ^ Benefit: Karl May - Life and Work. P. 418f.

- ^ Zaremba, Structures of Humor. P. 170.

- ↑ Plaul: Temporary editor. P. 189.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". P. 46.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". P. 55ff.

- ^ Düsing: Stories about history. P. 33.

- ^ Düsing: Stories about history. P. 20.

- ^ Düsing: Stories about history. P. 24f.

- ↑ Kahrs: Hundsfott. P. 59f.

- ↑ Kahrs: Hundsfott. P. 59f.

- ^ Siegfried Augustin: Introduction. In: Karl May. Happy hours. Entertainment papers for everyone. Reprint of the Karl May Society, Hamburg 2000, p. 29.

- ↑ Koch: The way to the “Kafferngrab”. P. 152.

- ↑ Ekkehard Koch: The 'Canada Bill' - Variation of a motif in Karl May. In: Claus Roxin, Heinz Stolte, Hans Wollschläger (ed.): Yearbook of the Karl May Society 1976. Hansa-Verlag, Hamburg 1976, ISBN 3-920421-31-0 , pp. 29-46 (32 f.). ( karl-may-gesellschaft.de ).

- ↑ Koch: The Canada Bill. P. 35.

- ↑ Koch: The Canada Bill. P. 39f.

- ↑ Koch: The way to the “Kafferngrab”. P. 152.

- ↑ Volker Griese: According to authentic sources: "A prince of the swindle". In: Communications from the Karl May Society. No. 82/1989, p. 24. ( karl-may-gesellschaft.de ).

- ^ Meier: Smaller house treasure stories. P. 30f.

- ↑ von Thüna, Ulrich: [article on] Robert Surcouf. In: Ueding: Karl May Handbook. P. 409f.

- ↑ Griese: According to authentic sources. P. 24.

- ^ Düsing: Stories about history. P. 20.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". P. 61.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". P. 61f.

- ↑ Walter Oldenbürger: [article on] Der Pflaumendieb. In: Ueding: Karl May Handbook. P. 363.

- ↑ Klußmeier: Karl May and the "Old Dessauer". P. 10f.

- ^ Ruprecht Gammler: Hussar pranks. In: Ueding: Karl May Handbook. P. 352.

- ↑ Stephan Kraus, Hartmut Wörner: Pacifism in May's work using the example of his soldiers' descriptions. In: Special issue of the Karl May Society. No. 13/1978, p. 39. ( karl-may-gesellschaft.de ).

- ^ Gammler: Hussar pranks. P. 352.

- ↑ Klußmeier: Karl May and the "Old Dessauer". P. 10.

- ↑ Kahrs: Hundsfott. P. 60.

- ^ Lorenz: Among the advertisers. P. 122.

- ↑ Plaul: Temporary editor. P. 174.

- ^ Meier: Foreword. P. 4.

- ^ Klaus Walther: Karl May. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-423-31056-1 , p. 20.

- ↑ Hartmut Kühne: [work article about] The Amsen dealer. In: Meier: Among the advertisers. P. 162.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". P. 61ff.

- ↑ Kahrs: Hundsfott. P. 61.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". P. 53.

- ↑ Kahrs: Hundsfott. P. 59f.

- ↑ Plaul: Temporary editor. P. 173f.

- ^ Kraus & Wörner, Pacifism in May's work. P. 39.

- ^ Kraus & Wörner, Pacifism in May's work. P. 39.

- ↑ Harald Lobgesang: Representation of the military in the Wild West volumes of Karl May. In: Special issue of the Karl May Society. No. 13/1978, p. 28. ( karl-may-gesellschaft.de ).

- ^ Benefit: Karl May - Life and Work. P. 418.

- ^ Gammler: Hussar pranks. P. 352.

- ↑ Klußmeier: Karl May and the "Old Dessauer". P. 11.

- ↑ Karl May: Geographical Sermons. In: shaft and hut. No. 24, 1875/76, p. 190. ( karl-may-gesellschaft.de ).

- ^ Kraus & Wörner, Pacifism in May's work. P. 42.

- ↑ Hymn of Praise: Representation of the military. P. 27.

- ^ Kraus & Wörner, Pacifism in May's work. P. 40f.

- ^ Debelius: editorial report. P. 460.

- ^ Debelius: editorial report. P. 484.

- ↑ Hans Wollschläger : Karl May - outline of a broken life - interpretation of personality and work - criticism . VEB Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1990, p. 46.

- ↑ Plaul: Temporary editor. P. 167.

- ^ Benefit: Karl May - Life and Work. P. 419.

- ↑ Eckehard Koch: [article about] Im Wollteufel. In: Ueding. Karl May Handbook. P. 346.

- ↑ Plaul: Temporary editor. P. 167.

- ^ Benefit: Karl May - Life and Work. P. 427.

- ^ Benefit: Karl May - Life and Work. P. 418f.

- ↑ Oldenbürger: The Plum Thief . P. 362.

- ↑ Hartmut Kühne: [article on] The Rose of Ernstthal. In: Meier: Among the advertisers. P. 302.

- ^ Lowsky: The War Chest. P. 358.

- ↑ Herbert Meier: Introduction. In: Meier, Smaller House Treasure Stories. P. 18.

- ↑ Meier: Introduction. P. 24.

- ↑ Augustine: Introduction. P. 23.

- ^ Meier: Smaller house treasure stories. P. 7, 24.

- ↑ Claus Roxin: [article about] Old Surehand. In: Ueding, manual. P. 205.

- ↑ Ekkehard: The way to the "Kafferngrab". P. 157.

- ^ Meier: Smaller house treasure stories. P. 30.

- ↑ Ekkehard Bartsch: Afterword. In: Karl May: Half-Blood . Karl-May-Verlag, Bamberg / Radebeul 1997, pp. 540-543.

- ↑ Engelbert Botschen: The anticipation of the work using the example of humoresques and village stories. In: Meier: Among the advertisers. P. 182 f.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". P. 31.

- ↑ Heermann: Karl May, the old Dessauer and an "old Dessauer". P. 60.

- ^ Lowsky: The War Chest. P. 358.

- ^ Lorenz: sovereign and smuggler prince. P. 366.

- ^ Debelius: editorial report. P. 501.

- ↑ Plaul: Karl May Bibliography

- ^ Debelius: editorial report. P. 471f.

- ↑ One only disguises oneself as the historical personalities Otto von Bismarck and Helmuth Karl Bernhard von Moltke

- ↑ Plaul: Karl May Bibliography

- ↑ Dating is currently being discussed anew

- ^ Anton Haider: From the "German House Treasure" to the book edition - comparative readings. Special issue of the Karl May Society No. 50/1984, pp. 20–24. ( karl-may-gesellschaft.de ).

- ^ Meier: Foreword. P. 4.