Ghosts

| Ghosts | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ghost horror ( Phasmatodea ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Phasmatodea | ||||||||||||

| Jacobson & Bianchi , 1902 | ||||||||||||

| Submissions | ||||||||||||

The ghosts or phasmids (Phasmatodea, Syn . : Phasmida) are an order of herbivorous insects . Often the order, referring to the different body shapes, is addressed as stick horror and ghost horror . In the 10th edition of Carl von Linnés " Systema Naturae " published in 1758 , the first three species were initially described under the generic name Gryllus . At the end of 2018, 3,286 valid species were known. Since the end of the 20th century in particular, several species have been discovered and described every year. Almost all representatives live in tropical and subtropical areas, especially in the oriental region, in Europe there are 17 species. The ghost horrors are characterized by their above-average size compared to all other insect orders and the often bizarre body shape that is reminiscent of parts of plants. Compared to other insects with a similar shape, the very short front chest ( prothorax ) is striking . The mid-chest ( mesothorax ), on the other hand, is always very long. The original features of the phasmids also include the presence of paired defensive glands , the openings of which are located in the prothorax.

Naming

The name ghost horror, derived from the scientific name Phasmatodea (Greek: Phasma = ghost), was given to these insects because of their appearance. Depending on the body shape and size, certain species are also called " stick insects ", "walking leaves" or "walking branches", whereby only the walking leaves form a taxonomic unit, namely the phyllioidea . Often, the ghost locusts are also called "stick insects" or "ghost locusts" in the German language, although locusts are usually only understood as representatives of the long-feeler terrors (Ensifera) and the short-feeler terrors (Caelifera). Ultimately, ghost horrors do not even literally belong to the horrors (= jumpers), as they cannot jump and usually only run or climb slowly to move.

The scientific name of the order is Phasmatodea and goes back to Jacobson and Bianchi in 1902. To this day one finds the name Phasmida Leach , 1815, especially in the English-speaking world and in the amateur area , which is considered to be a wrong derivation of the above-mentioned word Phasma and had to be corrected in Phasmatodea. In addition, the name Cheleutoptera, first used by Crampton in 1915, is synonymous with Phasmatodea.

The use of trivial names for individual species is particularly difficult . While in the English-speaking area mostly very uniform names are used for the respective species, fantasy names and collective names are often in use in German. The name " giant ghost insects " is used to designate different species that often only have one thing in common. The same applies to many large rod-shaped species that are usually referred to as " giant stick insects ". With the name " thorns-creeper " is usually meant Eurycantha calcarata . But this name is also occasionally used for completely different species, such as Heteropteryx dilatata , Aretaon asperrimus or even Extatosoma tiaratum . The use of country or region names in the species designation can be just as problematic, as dozens or even hundreds of species can occur in certain distribution areas. The assignment of names to species or higher taxa is often handled very superficially. For example, a comparison of different publications does not reveal whether “tree lobster” only refers to the species Dryococelus australis or whether other representatives of the Eurycanthini are also addressed in this way.

features

Body shape, color and size

Ghosts can have extremely long and thin (stick insects), leaf-like widened (walking leaves) or other shaped bodies. With their habitus , they almost always imitate parts of plants such as bark, twigs, branches or leaves in their environment ( phytomimesis ). This camouflage makes them difficult to spot, especially for their predators. In contrast to those of the grasshoppers, the legs are not transformed into jump legs, but are often included in the camouflage. The body is often covered with thorns, spines, or tubercles . The basic color of ghosts is usually brown or green, with white, yellow, red, blue and black body drawings appearing in addition to all transitions. The body length of species of ghosts can be between 15 and 328 millimeters. This means that even the smallest representatives are relatively large compared to those of other insect orders. The smallest known species so far is Miniphasma prima , of which only a 17.5 millimeter long female is known. The males should be a bit smaller. Other species that remain small are found in the genera Grylloclonia and Ommatopseudes . The species Phobaeticus chani, described by Philip Bragg in 2008, is considered to be the longest ghost insect and thus also the longest recent insect species . The described female of this species has a body length of 328 or 357 millimeters and a total length of 570 or 567 millimeters (data vary depending on the source). The females of various other Phobaeticus species also reach a length of over 300 millimeters. The males remain significantly smaller in these species. In the case of Phobaeticus chani , the male described is only 132 millimeters long. The largest known male phasmid, and thus also the longest recent male insect, is Phryganistria heusii , which has a maximum body length of 250.5 millimeters and a total length of more than 470 millimeters.

Head (caput) and antennae

The head of the phasmids is directed forward and usually so mobile that only it is moved along the edge of the leaf when eating, while the body remains at rest. Their mouthparts are of the chewing-biting type. These are characterized by a pair of upper jaws ( mandibles ) and a pair of lower jaws ( maxillae ), which access from the sides. In contrast, the lower lip ( labium ) and the overlying tongue ( glossa ) with the two secondary tongues ( paraglossae ) and the upper lip ( labrum ) are unpaired . The antennae , like those of all insects, are designed as whip antennae. The first limb, which is called the basal or shaft limb ( scapus ), is the only one with muscles. It is often widened and clearly distinguishable from all other antenna segments. The second, so-called reversible limb ( pedicellus ), together with all other limbs (flagellomeres) that form the flagellum, can move relative to the scapus. The scourge can vary greatly in length and number of limbs. The spectrum ranges from very short antennas with eight links to long antennas with around 100 links. The two representatives of the genus Paragongylopus , whose antennae consist of only three members, are an exception to the design of the antennae . While the first two links are very small, the third is greatly enlarged. The compound eyes are usually small to medium-sized. With some representatives, especially with flightable males, up to three single ocelles can be found between these (as with the males of the walking leaves). A wide variety of structures can be found on the head. Often there are two thorns or spikes that can act like horns. If there are more than two, they can appear like real crowns of thorns. Occasionally there are two vertically standing, semicircular, ear-shaped structures, so-called auricles.

Chest (thorax) with wings

The front chest (prothorax) of the phasmids is always very short. This feature is so characteristic that other phytomimetic insects, which are also rod-shaped, can be distinguished from the phasmids at first glance. For example, the elongated, rod-shaped catching horrors of the genera Thesprotia and Brunneria or the similarly designed short- antennae horror of the family Proscopiidae (horse head horror ) can be recognized as representatives of other orders due to the significantly longer front chest . The openings of the defensive glands, which are fully functional in many phasmids, are located in the prothorax. The mid-chest (mesothorax) is by far the longest segment of the body. The rear breast ( metathorax ) can also be very long, especially in rod-shaped species.

Terrors belong to the flying insects (pterygota), in which the adults have a pair of wings on the meso- and metanotum, but they can also be wingless or incompletely winged. All variants are possible in the design of the wings. Both the fore and hind wings can be reduced or completely absent. If the fore wings are present, they are always formed as tegmina , i.e. completely sclerotized and with recognizable veins. They can be very small (such as in Pseudophasma acanthonotum ) or as large as the abdomen (such as in the females of the walking leaves). If hind wings (alae) are present, they can also be reduced and, as in Hypocryrtus scythrus , be developed without the presence of forewings. Completely developed hind wings can be completely membranous, i.e. not very sclerotized. More often the anterior fields (between Costa and Cubitus) are more strongly sclerotized. They cover the abdomen, similar to the elytra of beetles . Your rear area, the anal field , is always membranous and allows some species to fly.

The wings are structured as follows: The first longitudinal vein (Costa) is unbranched and forms the outer edge (front edge) of the rear wing. It is absent on the forewings. The second longitudinal artery (subcosta) is also unbranched. The third longitudinal artery (radius) branches off on the rear wings in the direction of the radial sector, but remains unbranched on the front wings. The fourth longitudinal artery branches off at the base to form two longitudinal arteries, the anterior media and the posterior media. The fifth longitudinal artery (cubitus) is unbranched again. Behind it there are two anal arteries in the fore wings and significantly more in the hind wings. There the first seven wires are arranged in a group, all the rest in a further group. This wing structure is functionally comparable to that of the hemielytras of bed bugs . If there are wings, they can either be used for flying, complement the mimicry or be included in the enemy defense. Depending on their construction and size, they can be used for defensive stridulation or are intended to ward off potential enemies by showing bright colors or enlarging the body outline.

Abdomen (abdomen)

The abdomen consists of eleven sections, the first always being fused to the last breast segment, the metathorax, which can be seen on the back in most cases by a joint between the metanotum and the first abdominal segment, while on the Ventral side is a seamless fusion. The back plate ( tergite ) of the eleventh abdominal segment can be greatly reduced or elongated and is called the epiproct or supraanal plate. The paired paraprocts , next to which the cerci arise, have their origin on their ventral side . The cerci serve as tactile or clamp organs when mating or laying eggs. In the males of some representatives, there are thorn fields on the ventral epiproct or ventrally curved edges of the tenth back plate that have been converted into clamp organs to fix the female during mating. In addition, under the tenth tergum in many species there is a plate with a hook pointing backwards ( vomer ), which is used to anchor to the seventh abdominal sternum of the female. On the ventral side, the abdomen in the males consists of only nine and in the females of eight abdominal plates ( sterna ). The eighth sternum in females is often enlarged and is called the subgenital plate or operculum. It covers the genital organs including the ovipositor consisting of the appendages of the eighth and ninth abdominal segments . The ovipositor is therefore not a functional laying stinger, as is the case with long-feeler terrors. In many species this is formed as a secondary laying spine on the ventral side from the operculum and on the dorsal side either from the elongated epiproct (e.g. in the Heteropteryginae ) or the elongated tenth abdominal tergum (e.g. in the Eurycanthini).

Gender dimorphism

A pronounced sexual dimorphism is almost always found in phasmids . Often the differences in habitus between the sexes are so great that males and females have been described as different species, often even in different genera. B. happen with Phobaeticus serratipes . The males of the ghosts are consistently smaller and slimmer than the females. Even in species in which the sexes are approximately the same size, egg-laying females can still be clearly distinguished from the males by their swollen abdomen. There are often other differences in the formation of the wings. In addition to species with identical wing development, there are those in which the females have no or greatly reduced wings, while the males of the same species can have wings. These can not only be larger, but sometimes even enable flying. Egg-laying females, in particular, are almost never able to do this, even with fully developed wings. The coloring can also be very different. The nymphs of particularly strongly sexually dimorphic species usually resemble the females more closely. The males usually only show the coloration typical for their sex after molting to the imago .

Way of life

nutrition

All ghosts are phytophagous, i.e. herbivores . While there for a mono phage are species that specialize in certain plant species or groups, such as those on ferns commanded Fern stick insect ( Oreophoetes peruana ), others are very unspecialized and are considered polyphagous herbivores. In order to take in food, they usually only walk slowly around on the food plants. They are predominantly nocturnal. During the day they stay in the same place and hide in the food plants or on the ground in the layer of leaves.

Passive defense

For most species, the main strategy for defending against enemies is camouflage, more precisely in the imitation of dead or living parts of plants ( phytomimesis ). In addition to physique and color, many species have developed a corresponding behavior. Many species persist even when they are touched and do not attempt to escape or defend themselves. Others rock back and forth when moving, when the wind comes up or when they are touched, in order to imitate parts of plants moving in the wind. Some ghosts are able to change their lighter color during the day to a darker one at night (physiological color change ) by releasing hormones . Due to the action of the hormones, orange-red color grains can agglomerate or expand in the color cells of the skin and thus produce the color change. Many representatives simply let themselves fall with their legs stretched lengthways and then remain in this numbness on the ground, where they are difficult to see between other parts of the plant. Others also drop and then quickly run away when they hit the ground.

In order to escape predators, many species can throw off individual extremities at the designated break points between the thigh and thigh ring ( autotomy ) and replace them almost completely during the next molt ( regeneration ). This behavior can be observed especially in stick insects, especially in their nymphs.

Defense behavior

One of the characteristics of the ghosts is the presence of defensive glands. Species with functional defensive glands spray their defensive secretions through openings in the prothorax, which are located above the front legs. The secretion can either smell strong and mostly unsavory or even contain very aggressive chemical substances. Usually it is hardly camouflaged, partly diurnal species that have the most effective secretions. Their often conspicuous coloring is then to be understood more as a warning look . Members of the Pseudophasmatidae family in particular have aggressive secretions that are often corrosive and particularly attack the mucous membranes. Some of the substances contained were named after the ghosts that produced them, such as Anisomorphal after the genus Anisomorpha or Peruphasmal after the genus Peruphasma .

In addition to body color, some species also warn or scare their attackers by spreading their wings to appear larger or showing warning colors. Others produce noises ( defensive stridulation ) with the wings or the antennae . Another common strategy of larger, mostly well-thorned species (e.g. Eurycanthini, Extatosomatinae and Heteropteryginae ) is to hit enemies with their legs. To do this, the animals stretch their rear legs up in the air and stay there until the enemy approaches. Then they beat the thighs and splints of their hind legs together. They repeat this process at irregular intervals until the enemy gives up or is trapped, which can be quite painful due to the thorns on the hind legs.

Reproduction and development

Reproductive strategies

In addition to sexual reproduction , a large proportion of the species of ghosts is also capable of virgin generation (facultative parthenogenesis ). So you do not necessarily have to rely on males, as fertilization is not required. In automictic parthenogenesis, the egg cell's haploid set of chromosomes, which has meanwhile been haploid due to meiosis , is doubled again (e.g. in Leptynia species and some species of the genus Bacillus ). While in apomictic parthenogenesis the egg cells are generated by a mitotic division (e.g. in Timema species and some other Bacillus species). Most species only use virgin generation in nature when sexually mature females cannot find any males. Females almost always hatch from the unfertilized eggs. The higher number of female offspring increases the likelihood of finding males in the next generation or being found by a male. In order to preserve the species in a certain part of the range, only a period of time is bridged in which no or not enough males are available here.

In a few species it is assumed that parthenogenesis is mandatory, i.e. purely parthenogenetic reproduction. Nonetheless, the unfertilized eggs of these species can occasionally develop into animals that are phenotypically males and in some cases also have functional sexual organs . Since the sex determination of most ghost horrors is carried out by the XX / X0 system , non-disjunctions of the XX gonosomes lead to the formation of females with trisomal X chromosomes (XXX) and males with one X chromosome (X0) during the formation of the egg cells . In these parthenogenetically developed males, all cells are phenotypically male. Since they are genotypically not identical to real males due to the chromosome distribution, these intersex males are fertile but do not produce any male offspring. Males occasionally appear in the Great Wandering Leaf ( Phyllium giganteum ) or the Indian stick insect ( Carausius morosus ), but despite mating they do not result in a different, higher proportion of males in the progeny. Of many species, only females are known so far. It is assumed that among these there are also some that occur purely parthenogenetically in nature. Species with polyploid , mostly triploid chromosome sets can be found among the representatives with obligatory parthenogenesis .

In addition to parthenogenesis, hybridogenesis also takes place in some members of the genus Bacillus . Since the resulting specimens have “stolen” a set of chromosomes from the parent species, they are not referred to as species , but as Klepton (participle neuter to Greek κλέπτω - klepto = steal). This is expressed either in the abbreviation “ kl. “Between the scientific genus and species name or alternatively by a specific epithet in quotation marks , such as Bacillus kl. whitei or Bacillus "whitei" . Often, in the absence of another name, both parent species or subspecies are listed in the name connected by a hyphen, as in Bacillus kl. rossius-grandii benazzi . In some of these kleptons there is also androgenesis (egg cell without a chromosome set is filled by doubling the chromosome set of the sperm ) or gynogenesis (in haploid egg cell the chromosome set is doubled). Both forms lead to high juvenile mortality.

Dating and pairing

When looking for a partner, the smaller and more agile males are more active than the females. Many species that are winged in the male sex even fly around for this purpose. Fragrances, which the males follow, often serve as orientation. Once a female has been found, mating takes place. To do this, the male climbs on top of the female, often fixing the rear abdomen of the female with the forceps-shaped or clamp-like cerci or vomer or other structures. Then the male pushes his external genital organs under the subgenital plate of the female. An often round seed carrier ( spermatophore ) with a drainage tube is deposited there, which is only thrown off after it has been emptied. The sperm contained therein are stored by the female in the seminal pouch ( Receptaculum seminis ) until the respective maturing egg is fertilized. In some species, such as representatives of the genera Anisomorpha and Peruphasma , the males allow themselves to be carried by the females for weeks or even the rest of their lives. This as Mate Guarding ( Engl. : Mate = partners, guarding = guard) called behavior serves after copulation to aggravate further mating with females other males or impossible. In addition, repeated or long-lasting copulations have been observed. In Anisomorpha paromalus (syn. Anisomorpha monstrosa ) and Malacomorpha guamuhayaense , males were observed in mating with sub- adult females who continued to copulate with the exuuata for some time after their imaginal molt. Occasionally, several males try to mate with one female. In addition, mismatches occur again and again, especially when several species are socialized in terrariums, in which males try to mate with foreign females.

Eggs and egg laying

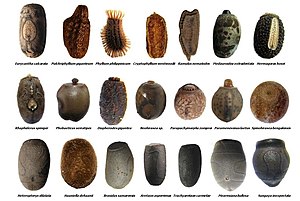

The eggs of the ghosts usually differ so much from one another that they are sometimes better suited to identifying the species than the animals themselves. This fact was already honored by John Parkinson , who already described the Malay giant ghost as Phasma dilatatum (today Hetropteryx dilatata ) in 1798 also depicted their egg. He was the first to depict the structures of a phasmid ice in detail. After him, Johann Jakob Kaup also dealt with this topic in more detail and laid the basis for today's ootaxonomy , a branch of special zoology that uses eggs in particular to determine (determine) the species with first comparative considerations .

Phasmid eggs often resemble plant seeds or animal droppings and are difficult to spot on or in the ground. The outer shell, the exochorion, usually has a very characteristic shape, color and surface. It can be smooth, porous, blunt, hairy or textured. The predominant colors are black and rather inconspicuous gray, beige and brown tones. The typical micropylar plate is found on the dorsal side of the eggs. The micropyle , a point-like point, which corresponds to the entry point of the sperm and which is used for gas exchange in hardened, i.e. already laid eggs, lies on this . At the front pole of the eggs there is a lid (operculum), which the nymph pushes open when it hatches. On this in turn sits a more or less conspicuous capitulum in the eggs of many species. The length of the eggs is measured from the edge of the operculum to the opposite pole. The width is determined in the dorsal view and the height in the lateral view . If the operculum is not at right angles to the longitudinal axis, but sits at an angle on the egg, this deviation is called the opercular angle and can also be used to determine the species.

The largest known ghost horror eggs are produced by the representatives of the subfamily Heteropteryginae. Especially the eggs of Haaniella echinata are the largest phasmid eggs with a length of up to twelve millimeters and a weight of just under 0.3 grams. The females of Asceles malaccae , which are just under ten centimeters long, lay eggs that are up to 15 millimeters longer, but are only about two millimeters in diameter. The length is due on the one hand to the almost two millimeters high, pointed capitulum, on the other hand due to the significantly longer tip at the lower end of the egg. This point is used to pierce the eggs into parts of the plant. Elongated, slender and pointed eggs are often pricked into parts of plants such as leaves or bark by other representatives. The eggs that are deposited in the bark are often particularly stable and reinforced like a chisel. When fixing such eggs, the egg is literally knocked into the bark by means of the abdomen. In species like Necroscia annulipes this can be heard acoustically as knocking. Other species stick their eggs individually or in groups to parts of the plant. Clutches that are deposited as compact egg packets, i.e. as ootheca , are known only from very few species. By far the majority of representatives simply drop their eggs on the ground or fling them away with their abdomen. The eggs are laid one at a time. Among the representatives who lay eggs in the ground using an ovipositor (e.g. Heteropteryginae , Obriminae and Eurycanthini), there are those who lay several eggs together, i.e. bury real clutches.

Some ghosts lay eggs that are strikingly similar to plant seeds with elaiosomes . The capitula of these eggs exert the same attraction on ants as the elaiosomes. The South African ghost insect Phalces brevis (Syn. Phalces coccyx ) occurs frequently in the heathland of the Eastern Cape Province , where myrmekochore plants predominate. Ants do not differentiate between elaiosomes and capitula and carry seeds and eggs in the same way into their nests, where the capitula as well as the elaiosomes are consumed without damaging the eggs. The eggs of the genus Extatosoma , which look like plant seeds, are also collected by the fire ants of the genus Leptomyrmex and brought into the storage chambers of the ant nest. It is very likely that the capitulum of the eggs will also be consumed here. Due to the climate in these buildings, the nymphs can develop very well and hatch there. For the first two to three days, their bodies are black and their heads are red. They look very similar to the fire ants and can leave the ant burrow unharmed.

The productivity of the individual species is very different and is often inversely related to life expectancy. The mostly very long-lived representatives of the Dataminae subfamily often only lay one or two eggs per week. The most productive species are not only significantly shorter-lived, but also lay much smaller eggs compared to their body size. With up to 2500 eggs, at times 21 eggs a day, there are representatives of the Phasmatidae family such as Acrophylla titan , Anchiale briareus and Hermarchus leytensis .

development

Terrors are hemimetabolic insects . The development time of the embryos in the egg is about three to twelve months, depending on the species, in exceptional cases up to three years. The nymphs grow into adult insects in three to twelve months . Especially in variegated species, they often differ in their coloring from their parents. Species with no or less aggressive defensive secretions often show the bright colors of their parents only after the imaginal moult, as can be seen in Paramenexenus laetus or Mearnsiana bullosa . Well-fortified species whose nymphs already have functioning defensive glands, such as the fern stick insect ( Oreophoetes peruana ) or the velvet insect ( Peruphasma schultei ), show a warning color similar to that of their parents early on. Females molt six times during adolescence, while males are adult after five, more rarely after four molts (e.g. in the case of the walking leaves). After molting, the skin is consumed in particular because of the trace elements it contains .

The determination of the sex ( Geschlechtsdetermination met), as with all insects process that during embryogenesis independently in each cell expires (cell-autonomous). Occasionally, animals can develop in which areas with male and female cells are distributed like a mosaic in the body. Among these rarely occurring gynanders or mosaic hermaphrodites, the characteristics of the male are often concentrated in one half of the body and those of the female in the other. Such animals are called half-sided hermaphrodites or half-sided gynanders. They always have a lower life expectancy than males or females of the respective species. Gynanders have been documented for the Indian stick insect ( Carausius morosus ), the Malay giant ghost insect ( Heteropteryx dilatata ), the fern stick insect ( Oreophoetes peruana ), the little stick insect ( Aretaon asperrimus ) , the Australian stick Insect ( Extatosoma tiaratum ), the Wandering bean ( Diapherodes gigantea ), the Vietnam-stick insect ( Ramulus artemis ), the Gallic Mediterranean Stabschrecke ( Clonopsis gallica ), the Great Wandering leaf ( Phyllium giganteum ) and for bioculatum Phyllium , Phyllium westwoodii , Chitoniscus sarrameaensis , Ocnophiloidea regularis and Tropidoderus childrenii .

In the phasmids, the adult females live on average significantly longer than the males, namely between three months and a year. The males are usually only three to five months old; some of the Wandering Leaves only live a month or so. The highest registered age was reached by a female Haaniella scabra from Sabah that Oskar V. Conle kept for more than five years. In general, many members of the Hetropterygigae family are extremely long-lived.

Distribution and habitats

Ghost horrors can be found in all tropical and subtropical areas of the world. They achieve the greatest biodiversity in the oriental region with around 1,500 known species, followed by the Neotropic with over 1,000 species and the Australis with more than 440 species. In the rest of the distribution area, the number of species from Madagascar across Africa and the Nearctic to the Palearctic decreases. In the Mediterranean and Middle East only a few species are located. Only in the area of the Great Lakes in North America do ghosts naturally occur north of the 45th parallel. However, there are some populations in England that can be traced back to terrarium animals that have escaped. Acanthoxyla prasina , Clitarchus hookeri , the Mediterranean stick insect ( Bacillus rossius ) and the Indian stick insect ( Carausius morosus ) were able to survive in the mild English climate .

In southern Europe there are the Spanish stick insects ( Pijnackeria hispanica ), the Gallic Mediterranean stick insects ( Clonopsis gallica ), four species of the genus Leptynia , and six species of the genus Bacillus , e.g. B. the Mediterranean stick insect ( Bacillus rossius ), of course.

The greatest species density is found in habitats with lush vegetation. In the first place are forests and of these especially the different forms of the tropical rainforest . The number of species decreases in drier areas as well as in higher and therefore cooler regions. The representatives of the genus Monticomorpha live in the highest distribution area . So Monticomorpha flavolimbata on the Ecuadorian volcano Cotopaxi to find in 5,000 meters near the snow line.

Systematics

External system

The position of the Phasmatodea within the superordinate order of the Neuflügler (Neoptera) is partly controversial. In this superordinate order, they are always assigned to the Polyneoptera, a group that has not yet been systematically clarified. Their further classification varies as does that of other orders placed here. The overview presented here follows the phylogenetic system of insects :

| Polyneoptera |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

This classification is supported and substantiated by more recent studies based on genetic analyzes . According to Misof et al. (2014), the following relationships between species, according to which the sister group to the Gespenstschrecken the embioptera is (Embioptera) and the notoptera with the Gladiator terror (Mantophasmatodea) and the grylloblattidae are to provide (Grylloblattodea) in their common relationship:

| Polyneoptera |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

The splitting off of the Timemas (Timematodea) from the Phasmatodea, proposed by Oliver Zompro in the past, is generally not recognized.

Internal system

The system of ghost horrors is subject to frequent changes and is sometimes very controversial. One of the reasons for this is that new species are constantly being found and processed. On average there have been a few dozen new descriptions per year since the end of the 20th century. At the same time, almost as many species are recognized as synonyms and withdrawn again. The findings resulting from this are reflected in frequent revisions . One was the work published in 2004 by Oliver Zompro , in which the Timematodea was detached from the order of the Phasmatodea and placed in the relationship of the stonefly (Plecoptera) and the tares spinner (Embioptera). In 2008 alone there were two more major works which, in addition to the establishment of new taxa down to the subfamily level , also resulted in the reallocation of many taxa down to the family level. The systematics shown here up to the tribe level follows the Phasmida Species File Online (as of November 2018) and thus takes into account the currently recognized systematics and thus not the status of the Timematodea proposed by Zompro. Furthermore, the fossil family Archipseudophasmatidae, which is marked with "†" and can be assigned to the Areolatae , has been added:

Suborder Agathemerodea

- Agathemeridae

Bradler , 2003

- Agathemerinae Bradler , 2003

- Agathemerini Bradler , 2003

- Agathemerinae Bradler , 2003

Subordination Timematodea

- Timematidae Caudell , 1903

- Timematinae Caudell , 1903

- Timematini Caudell , 1903

- Timematinae Caudell , 1903

Subordination Verophasmatodea

Partial order Anareolatae Redtenbacher , 1906

-

Diapheromeridae Kirby , 1904

-

Diapheromerinae Kirby , 1904

( Syn. = Bacterinae Handlirsch , 1930)- Diapheromerini Kirby , 1904

- Ocnophilini Günther , 1953

- Oreophoetini Zompro , 2001

-

Necrosciinae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

(Syn. = Candaulae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893)

(Syn. = Necroscidae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893)

(Syn. = Neohiraseini Hennemann & Conle , 2008)- Necrosciini Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

-

Pachymorphinae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

(Syn. = Pachymorphae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893)- Gratidiini Cliquennois , 2004

- Hemipachymorphini Günther , 1953

- Pachymorphini Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

-

Palophinae Kirby , 1896

- Palophini Kirby , 1896

-

Diapheromerinae Kirby , 1904

-

Phasmatidae Gray, GR , 1835

(Syn. = Lanceocercata)

(Syn. = Phasmidae Leach , 1815)-

Cladomorphinae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

(Syn. = Phibalosomini Redtenbacher , 1908)- Cladomorphini Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

-

Cladoxerini Karny , 1923

(Syn. = Baculini Günther , 1953) -

Cranidiini Günther , 1953

(Syn. = Craspedoniini) - Haplopodini Günther , 1953

- Hesperophasmatini Bradley & Galil , 1977

- Pterinoxylini Hennemann , Conle & Perez-Gelabert , 2016

- Teruelphasmini Yong , 2017

-

Clitumninae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

-

Clitumnini Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

(Syn. = Ramulini Günther , 1953) - Medaurini Hennemann & Conle , 2008

- Pharnaciini Günther , 1953

-

Clitumnini Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

-

Extatosomatinae Sellick , 1997

- Extatosomatini Sellick , 1997

-

Lonchodinae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

(Syn. = Prisomerinae Karny , 1923)- Eurycanthini Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

-

Lonchodini Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

(Syn. = Menexenini)

-

Phasmatinae Gray, GR , 1835

(Syn. = Acrophyllini Redtenbacher , 1908)- Acanthomimini Günther , 1953

- Acanthoxylini Bradley & Galil , 1977

- Phasmatini Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

-

Platycraninae Brunner from Wattenwyl , 1893

- Platycranini Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

-

Tropidoderinae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

- Gigantophasmatini Hennemann & Conle , 2008

- Monandropterini Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

- Tropidoderini Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

- Xeroderinae Günther , 1953

- without assignment

- Achriopterini Günther , 1953

- Stephanacridini Günther , 1953

-

Cladomorphinae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

Partial order Areolatae Redtenbacher , 1906

Superfamily Aschiphasmatoidea Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

-

Aschiphasmatidae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

- Aschiphasmatinae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

(Syn. = Xylobistinae Zompro , 2004)-

Aschiphasmatini Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

(Syn. = Xylobistini) - Dajacini Bragg , 2001

-

Aschiphasmatini Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

- Aschiphasmatinae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

-

Damasippoididae Zompro , 2004

- Damasippoidinae Zompro , 2004

- Damasippoidini Zompro , 2004

- Damasippoidinae Zompro , 2004

-

Prisopodidae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

-

Korinninae Günther , 1953

- Korinnini Günther , 1953

-

Prisopodinae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

(Syn. = Xylobistini)- Paraprisopodini Zompro , 2004

- Prisopodini Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

-

Korinninae Günther , 1953

Superfamily Bacilloidea Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

-

Anisacanthidae Günther , 1953

-

Anisacanthinae Günther , 1953

- Anisacanthini Günther , 1953

- Leiophasmatinae Cliquennois , 2008

- Xerantherinae Cliquennois , 2008

-

Anisacanthinae Günther , 1953

-

Bacillidae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

-

Antongiliinae Zompro , 2004

- Antongiliini Zompro , 2004

- Leprodini Cliquennois , 2006

- Pseudodatamini Zompro , 2004

- Tuberculatocharacini Zompro , 2005

- Xylicini Günther , 1953

- Bacillinae Brunner from Wattenwyl , 1893

-

Macyniinae Zompro , 2004

- Macyniini Zompro , 2004

-

Antongiliinae Zompro , 2004

-

Heteropterygidae Kirby , 1896

-

Dataminae Rehn, JAG & Rehn, JWH , 1939

- Datamini Rehn, JAG & Rehn, JWH , 1939

-

Heteropteryginae Kirby , 1896

- Heteropterygini Kirby , 1896

-

Obriminae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

(Syn. = Therameninae Karny , 1923)- Tisamenini Hennemann , Conle , Brock & Seow-Choen , 2016

- Miroceramiini Zompro , 2004

-

Obrimini Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

(Syn. = Eubulidini Zompro , 2004)

-

Dataminae Rehn, JAG & Rehn, JWH , 1939

Superfamily Phyllioidea Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

- Phylliidae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

- Phylliinae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

- Nanophylliini Zompro & Grösser , 2003

- Phylliini Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

- Phylliinae Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

Superfamily Pseudophasmatoidea Rehn, JAG , 1904

-

Heteronemiidae Rehn, JAG , 1904

(Syn. = Bacunculidae)- Heteronemiinae Rehn, JAG , 1904

- Heteronemiini Rehn, JAG , 1904

- Paraleptyniini Zompro , 2004

- Pygirhynchini Redtenbacher , 1906

- Heteronemiinae Rehn, JAG , 1904

-

Pseudophasmatidae Rehn, JAG , 1904

-

Pseudophasmatinae Rehn, JAG , 1904

- Anisomorphini Redtenbacher , 1906

- Pseudophasmatini Kirby , 1904

-

Stratocleinae Günther , 1953

- Stratocleini Günther , 1953

-

Xerosomatinae Bradley & Galil , 1977

- Prexaspini Zompro , 2004

- Setosini Zompro , 2004

- Xerosomatini Bradley & Galil , 1977

-

Pseudophasmatinae Rehn, JAG , 1904

Family † Archipseudophasmatidae Zompro , 2001

Fossil evidence

The oldest fossil ghosts come from the Triassic of Australia . Younger representatives of the order can also be found in Baltic, Dominican and Mexican amber (all Eocene to Miocene ). Most of them are larvae. From the fossil family Archipseudophasmatidae, the species Archipseudophasma phoenix , Sucinophasma sheet odeophila and Pseudoperla gracilipes from Baltic amber have been described. The second species of the genus Pseudoperla , Pseudoperla lineata , mentioned in some publications , is today, depending on the source, either regarded as a synonym of the aforementioned species or as Balticophasma lineata in its own genus. In addition to these inclusions , fossils also testify that ghost horrors once had a much larger area of distribution. The 47 million year old imprint of a walking leaf described as Eophyllium messelensis was found in the Messel Pit .

Ghosts and humans

Phasmids are increasingly attracting the interest of terrarium keepers . This development forces the introduction of alien species into climatically suitable areas. Since these neozoa , like some endemic species, can become pests under certain circumstances , this can cause problems in agricultural areas. On the other hand, the increased interest ensures awareness of the hazard and any protective measures that may be required.

Use by humans

So far there are only a few examples of the use of phasmids by humans. It is known that the indigenous population in Borneo eat the very large eggs of some Haaniella species. They are not only valued for their high protein content, but are also said to help against diarrhea when cooked. In Europe, the Indian stick insect ( Carausius morosus ) has been used as an experimental animal at universities and as a demonstration insect for camouflage, locomotion, development, sensory performance and metabolism in schools and teaching since the end of the 19th century , which has also earned it the nickname laboratory stick insect or laboratory stick insect .

Terrors as pets

In recent times, ghost horrors have been enjoying increasing popularity in terraristics . However, some species have been in human care for a long time. For example, Eurycnema versirubra (Syn. Eurycnema versifasciata ) was already kept as a pet by the indigenous people of the Sunda Islands . The number of species in breeding in enthusiasts' terrariums has been increasing continuously for years. A real boom began in the 1980s. During this time, various associations were founded that have made the keeping and breeding of ghost horrors their task. For example, the Phasmid Study Group was founded in England , the greatest achievement of which is the establishment of an internationally standardized list of around 400 species of ghost terrarium previously kept in terrariums (see also: List of PSG species ). The Dutch - Belgian PHASMA also deals exclusively with ghosts and publishes the magazine PHASMA at irregular intervals. In Germany many phasmid lovers are in the ZAG (Central Working Group) Wirbellose e. V. organized.

Ghosts as pests

Since all representatives of the order are phytophagous, individual species can also appear as pests on cultivated plants . In the botanical gardens of Central Europe, for example, exposed or escaped stick insects are occasionally found as pests. In addition to the Indian stick insect ( Carausius morosus ), the Vietnam stick insect ( Ramulus artemis ) and the pink winged stick insect ( Sipyloidea sipylus ) have caused considerable damage. B. in the Botanical Garden Munich . Since the danger posed by escaped animals to agriculture and forestry is very great, especially in tropical regions, the keeping of certain species or entire groups of insects in some countries requires a permit or is restricted to research. In the south of the USA , for example, the Australian ghost insect ( Extatosoma tiaratum ) has appeared as a pest, so that its keeping there is now subject to approval.

Serious damage to forestry can occur in particular with monocultures . From Australia to South America introduced species Echetlus evoneobertii in Brazilian eucalyptus - plantations become enterprising forest pest serious one. In Australia itself, Didymuria violescens usually causes major damage in the mountain forests of New South Wales and Victoria every two years . In 1963, hundreds of square kilometers of eucalyptus forest were completely defoliated. Furthermore, Podacanthus wilkinsoni and Anchiale austrotessulata also become pests in the forests of Australia when they multiply on a large scale . The North American oak forests are afflicted by Megaphasma dentricus in the eastern United States and by Diapheromera femorata in Texas and Arkansas . In China, too, several species have repeatedly caused great damage. One should mention here Baculonistria alba , which defoliated approx. 800 hectares of teardrop cypress ( Cupressus funebris ) in 2005 , whereby the trees died on over 40 hectares. Between 1989 and 1990, were up to 3,500 hectares of forest bill Chestnut ( Castanopsis fissa ) of up to 450 animals of the species Micadina yingdensis per tree infested. From Ramulus minutidentatus less than ten years later were even 2,000 to 5,000 animals per tree on the Lindenart Tilia mandshurica counted. In some cases, these mass occurrences could only be regulated through the widespread use of insecticides .

Hazards and protective measures

Little is known about the endangerment of species of ghosts because of their hidden way of life. The destruction of habitats and the introduction of predators , however, often have particularly massive effects on species that occur in very small distribution areas such as islands or naturally limited habitats. The introduction of the brown rat to Lord Howe Island in 1918 meant that the entire population of the endemic tree lobster ( Dryococelus australis ) was considered extinct as early as 1930 . Only the discovery of a population of fewer than 30 animals on the neighboring island of Ball's Pyramid , 23 kilometers away, proved their survival. Because of the small size of the population and because the habitat of the animals found there was limited to an area of 6 m × 30 m, it was decided to carry out a breeding program. The tree lobster is classified as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List .

Repeated visits to certain habitats show that this is not an isolated case. Parapachymorpha spinosa was found around the Pak Chong train station in Thailand in the late 1980s . After the station area was expanded, the species could not be detected either here or in the vicinity from the end of the 1990s.

Protective measures are initiated by specialists and enthusiasts, especially for species with a small distribution area. The velvet insect ( Peruphasma schultei ), discovered in 2004 in the Cordillera del Condor in northern Peru , occurs in an area of only five hectares. Since there are other endemic species in this area, it has been placed under protection by the Peruvian government. The INIBICO NGO (a Peruvian nature conservation organization) also started a breeding program for the velvet insect as part of a benefit project for the residents of the Cordillera del Condor National Park. The aim of the project, which was scheduled to run until the end of 2007, was to release or sell half of the offspring. Thanks to the phasmid lovers, this species was able to be secured in its population and is now one of the most common phasmids in the terrarium.

Highly specialized, for example monophageous species, especially if they are only distributed on certain islands, can even become extinct completely. On the island of Rodrigues , the phasmids Xenomaches incommodus , which is quite conspicuous due to their green base color and red antennae, and their food plant, the palm Latania verschaffeltii , were endemic. After the disappearance of the palm species, the ghost insect was no longer found and is considered extinct.

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Paul D. Brock , Thies H. Büscher & Edward W. Baker: Phasmida Species File Online . Version 5.0. (accessed November 30, 2018)

- ↑ a b Phasmatodea in Fauna Europaea , as of March 19, 2015.

- ↑ a b c d e Dr. Dr. hc Bernhard Grzimek , in Grzimeks Tierleben , Volume 2: Insects ( ISBN 3-423-05970-2 )

- ↑ Oliver Zompro : Poles, ghosts, walking leaves - phasmid systematics at a glance I. , Arthropoda 17 (1) April 2009, Sungaya-Verlag Kiel. ISSN 0943-7274

- ↑ a b c d e Roy Bäthe, Anke Bäthe & Mario Fuß: Phasmiden , Schüling Verlag, Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-86523-073-7

- ↑ Spiegel Online - Michael Lenz: Save the tree lobster!

- ↑ scinexx - the knowledge magazine: tree lobsters have no relatives

- ↑ Oliver Zompro: Dwarf forms of Phasmatodea - the little ones among the giants , Arthropoda 16 (3) November 2008, Sungaya-Verlag Kiel. ISSN 0943-7274

- ↑ Oliver Zompro: The longest stick insect - the longest living insect , Arthropoda 16 (4) December 2008, Sungaya-Verlag Kiel. ISSN 0943-7274

- ^ Spiegel Online for the new description of Phobaeticus chani

- ↑ a b Natural History Museum UK about the longest insect in the world (archive October 2008)

- ↑ Oliver Zompro: Paragongylopus plaumanni Zompro , 2000 - one of the strangest phasmids , Arthropoda 17 (1) April 2009, Sungaya-Verlag Kiel. ISSN 0943-7274

- ↑ a b c d e Christoph Seiler, Sven Bradler & Rainer Koch: Phasmids - care and breeding of ghost horrors, stick insects and walking leaves in the terrarium - bede, Ruhmannsfelden 2000, ISBN 3-933646-89-8

- ↑ Thies H. Büscher: Gynandromorphism - half man, half woman - curious hybrid beings; a report with a particular focus on Gynander in the order Phasmatodea (Insecta) . Arthropoda Popularis, 3/4 2015, ZAG Wirbellose eV, Dessau-Roßlau 2015, pp. 26–37, ISSN 2190-3476

- ↑ a b Detlef Großes : Wandering Leaves , Edition Chimaira, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-930612-46-8

- ^ Ingo Fritzsche : On the discovery of Malacomorpha guamuhayaense Zompro & Fritzsche , 2008 , Arthropoda 16 (1) March 2008, Sungaya-Verlag Kiel. ISSN 0943-7274

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Phasmatodea page by Oskar V. Conle and Frank H. Hennemann

- ↑ a b c Ingo Fritzsche: Poles - Carausius, Sipyloidea & Co. , Natur und Tier Verlag, Münster 2007, ISBN 978-3-937285-84-9

- ↑ SG Compton and AB Ware: Ants disperse the elaiosome-bearing eggs of an African stick insect . Psyche Volume 98, 1991, pp. 207-213. [1]

- ↑ Stephan Schorn: The Australian giant ghost insect Extatosom tiaratum , Natur und Tier Verlag, Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-86659-123-3

- ↑ Bernhard Misof et al. : Polygenomics resolves the timing and pattern of insects evolution , Science 346, 763, 2014, by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington DC, (print) ISSN 0036-8075 , (online) ISSN 1095-9203

- ↑ Oliver Zompro: The system of winged insects (Pterygota) , Arthropoda 16 (1) March 2008, Sungaya-Verlag Kiel. ISSN 0943-7274

- ↑ Oliver Zompro: Revision of the genera of the Areolatae, including the status of Timema and Agathemera (Insecta, Phasmatodea) . Goecke & Evers Verlag, Keltern, 2004, ISBN 3-931374-39-4

- ^ Frank H. Hennemann & Oskar V. Conle : Revision of Oriental Phasmatodea: The tribe Pharnaciini Günther, 1953, including the description of the world's longest insect, and a survey of the family Phasmatidae Gray, 1835 with keys to the subfamilies and tribes ( Phasmatodea: Anareolatae: Phasmatidae) (Zootaxa 1906), Magnolia Press, Auckland, New Zealand, 316 pp .; 30 cm. 15 Oct. 2008, ISBN 978-1-86977-271-0 (paperback), ISBN 978-1-86977-272-7 (online edition) (pdf of the abstract at www.mapress.com ; PDF; 48 kB)

- ↑ Nicolas Cliquennois : 2008. Ann. Soc. entomol. Fri. ns 44 (1): 60

- ↑ George O. Poinar, Jr .: Life in Amber . 350 pp., 147 figs., 10 plates, Stanford University Press, Stanford (Cal.) 1992. ISBN 0-8047-2001-0

- ↑ Wolfgang Weitschat and Wilfried Wichard: Atlas of plants and animals in Baltic amber , 256 p., Numerous. Fig., Pfeil-Verlag, Munich 1998. ISBN 3-931516-45-8

- ↑ Oliver Zompro: Extinct exotic insects in Europe , Arthropoda 16 (3) November 2008, Sungaya-Verlag Kiel. ISSN 0943-7274

- ↑ Biolib - Taxon profile for Archipseudophasmatidae (Engl.)

- ↑ Science ticker - “Walking leaves” are living fossils

- ↑ Siegfried Löser: Exotic insects, millipedes and arachnids - instructions for keeping and breeding . Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-8001-7239-9

- ↑ a b Oliver Zompro: Did you know? - Remarkable things about phasmids , Arthropoda 17 (1) April 2009, Sungaya-Verlag Kiel. ISSN 0943-7274

- ↑ Phasmid Study Group Culture List ( Memento from December 5, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) (English)

- ↑ Paul D. Brock & Jack W. Hasenpusch : The complete fell guide to stick and leaf insects of Australia , Csiro Publishing, Collingwood, Auaralia, 2009, pp. 74-75, ISBN 978-0-643-09418-5

- ↑ Dryococelus australis in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Retrieved on March 1 of 2009.

- ↑ Page of the Peruvian conservation organization INIBICO

literature

- Redtenbacher, J. (1906): The insect family of the phasmids. Vol. 1. Phasmidae Areolatae. pp. 1-180, pls. 1-6. Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig. online (PDF; 56.7 MB)

- Brunner von Wattenwyl, K. (1907): The insect family of the phasmids. Vol. 2. Phasmidae Anareolatae (Clitumnini, Lonchodini, Bacunculini). pp. 181-340, pls. 7-15. Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig. online (PDF; 41.9 MB)

- Redtenbacher, J. (1908): The insect family of the phasmids. Vol. 3. Phasmidae Anareolatae (Phibalosomini, Acrophyllini, Necrosciini). pp. 341-589, pls. 16-27. Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig. online (PDF; 71.4 MB)

Web links

- www.phasmatodea.com - the world's largest website on stick horrors and ghosts by Oskar V. Conle and Frank H. Hennemann, u. a. with photos, forum and breeding instructions from Bruno Kneubühler

- www.insectissima.de - Website from Sascha Eilmus and Alexander Dernbach, among others, about ghost horrors

- www.phasma.eu - Website of the Dutch-Belgian PHASMA

- phasmid-study-group.org Website of the Phasmid Study Group (English)