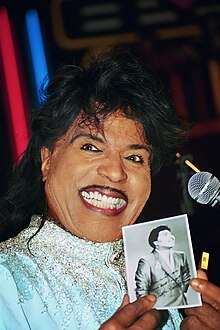

Little Richard

Little Richard (born Richard Wayne Penniman December 5, 1932 in Macon , Georgia , † May 9, 2020 in Tullahoma , Tennessee ) was an American rock 'n' roll singer, pianist and songwriter. During the most successful phase of his career with Specialty Records in the mid-1950s, the African-American musician combined stylistic elements from blues , gospel and rhythm and blues under the new genre name "Rock 'n' Roll" and brought them into the musical mainstream . After high placements in the rhythm and blues charts , which are dominated by black performers, he managed to crossover into the genre-independent American pop market . His fast and powerful piano playing, his loud and over-the-top singing and his energetic concerts inspired many well-known musicians.

After several years of retreat for religious studies, Little Richard began a comeback in the 1960s , for which he further developed his sound towards soul and funk . Without being able to build on his earlier sales successes, he increased the extravagance of his stage appearances through self-staging and elements of travesty . Since the 1980s, Little Richard has only sporadically been in the recording studio or on stage. Due to his genre-defining and much-covered songs and their chart successes, Little Richard is one of the pioneers and main representatives of rock 'n' roll, which is why he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1986 as one of the first musicians .

Life

Childhood, youth and first recordings (1932–1955): Rhythm and Blues

Richard Wayne Penniman was on December 5, 1932 in Macon in the US state of Georgia the third child of Leava Mae and Charles "Bud" Penniman. He grew up with seven brothers and five sisters. In the family he was nicknamed "Little" ("smaller") Richard because of his height at the time. As a club owner, Bud Penniman ensured a modest livelihood for the family, among other things by trading black liquor. As a frequent attendee of services in the local Pentecostal Church and the Baptist and Methodist congregations, Little Richard developed a taste for gospel music , which he performed as a member of The Tiny Tots at performances in churches and in the streets of Macon and the surrounding area. This gave rise to his desire to become a priest . The young singer made a guest appearance at a concert by Sister Rosetta Tharpe in the Macon City Auditorium, which was welcomed by the audience. Even as an adolescent, Little Richard had homosexual tendencies that met with ridicule in his family environment and disapproval from his father.

Since he found his parents' home cramped, he left high school at the age of 14 and joined several vaudeville and medicine shows , where he could deepen his experience as a singer and work on his stage presence. He wore his hair as a mighty pompadour hairstyle and took his nickname "Little Richard" as a stage name . Finally, around 1951 in Atlanta , a center of the rhythm and blues scene at the time, he got an engagement with jump blues singer Billy Wright , from whose show he took travesty elements such as women's costumes and make-up . Wright also gave him a studio appointment for his first blues recordings with RCA Records . Back in Macon, Little Richard made friends with the rhythm and blues musician Esquerita , who taught him how to play the piano particularly "wild". With the RCA single Every Hour , Little Richard had a first regional radio hit in 1952. This reconciled him with his father, who was shortly afterwards killed in a shootout in front of his club. Little Richard then took a job as a dishwasher in the restaurant of the local greyhound bus station to support the family. The unsatisfactory and low-paid work prompted him to devote himself professionally to music and strive for commercial success.

Little Richard played in clubs in the southern states with the newly formed band The Tempo Toppers and learned the typical Creole blues style from Earl King in New Orleans . In 1953, the producer Johnny Otis discovered the group and their front man in Houston , who marketed himself as the "King and Queen" of the blues, and enabled the next recordings on Peacock Records . The collaboration, from which only a few blues and gospel numbers emerged apart from Directly from My Heart to You , was not free of conflicts. So Little Richard fought in a royalty dispute with the owner of the label Don Robey . After some time as a solo artist, Little Richard put together the core of his future live band The Upsetters from the drummer Charles "Chuck" Connor and the saxophonist Wilbert "Lee Diamond" Smith . Subsequent tours throughout Kentucky , Georgia and Tennessee came with an over the pace Toppers significantly harder rhythm-and-blues program, including an early version of Little Richard's composition Tutti Frutti , expressed the public good.

Breakthrough and career high point (1955–1957): Rock 'n' Roll

On the advice of the singer Lloyd Price , Little Richard sent a demo tape to Art Rupe , head of the California independent label Specialty Records in Los Angeles, in the spring of 1955 . Its A&R manager and producer Bumps Blackwell was persuaded by Little Richard's persistent telephone inquiries to start a first recording session in Cosimo Matassa's J&M Recording Studio in New Orleans. He booked with Earl Palmer on drums, Lee Allen and Alvin "Red" Tyler on saxophones and Frank Fields on bass from his renowned studio band . In this constellation and with changing guitarists, Little Richard's greatest hits and sales successes were created in five studio sessions over the next two years, including Tutti Frutti, Long Tall Sally , Ready Teddy , Rip It Up, Good Golly Miss Molly, Jenny Jenny and The Girl Can ' t Help It. Little Richard went into the studio in California for three recordings, where he was accompanied once by Guitar Slims Band under the direction of Lloyd Lambert and twice by the Upsetters. His live band can also be heard on recordings from Washington that were made during a concert tour.

For Specialty, Little Richard recorded material for almost 20 singles , six EPs and the three albums Here’s Little Richard , Little Richard and The Fabulous Little Richard from 1955 to 1957 . He achieved his success by going on extensive concert tours with the Upsetters and having his songs promoted in short appearances in music films. Little Richard was dissatisfied with the contract with Specialty Records, as the majority of the income remained with Art Rupe through the marketing of the pieces of music by the label's own music publisher Venice Music. This overreaching promoted the early break of the cooperation with Specialty Records.

Called a preacher (1957–1964): Gospel

At the end of September 1957 Little Richard flew alongside Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent for a fourteen-day tour to Australia. During the flight he interpreted the propeller engines , which glowed against the night sky because of the heat on the wings, as angels. At a concert in Sydney on October 4th, he observed the Sputnik 1 satellite , which he had just launched and which he perceived as a ball of fire on its way into orbit . He understood these experiences as warnings from God, and he decided to end his unsteady life as a rock 'n' roll musician and become a priest. In relation to his environment and his followers, who reacted with incomprehension, Little Richard justified his withdrawal with his previous vicious and dissolute lifestyle, which was not compatible with his religious convictions.

Little Richard began preaching in various Revival churches and in the fall of 1958 began a three and a half year theological training with Seventh-day Adventists at Oakwood Bible College in Huntsville , Alabama. Church leaders appreciated Little Richard's popularity and ability to inspire others, and tolerated the excitement he caused by his extroverted appearance on campus, as well as the frequent violations of school rules. He married Ernestine Campbell, a Washington, DC secretary, in July 1959 and divorced in 1964. On the one hand, his wife was bothered by the public that Little Richard's celebrities brought with it, on the other hand, he admitted in retrospect that he had not made sufficient efforts to get married because of his homosexual orientation.

Little Richard made this turning point in his career musically, as he now mainly devoted himself to the gospel style. For George Goldner's record label End Records, Richard recorded several gospel songs in mid-1959, which were released in album format as Pray Along With Little Richard Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 by the associated record company Golddisc Records. Bumps Blackwell, who had meanwhile switched to Mercury Records , was able to win Richard over for a few studio appointments in 1961. The recordings were made under the direction of Quincy Jones and were released as LP It's Real and later as Little Richard. King of Gospel Singers released. While other recordings of religious songs for Atlantic Records were not very successful, Specialty Records gradually marketed all of Little Richard's recordings from its own archives, including the early blues numbers that were found to be too weak at the time, and was thus able to regularly publish records with original material until 1960.

The English music promoter Don Arden invited Little Richard to tour England with his former Specialty colleague Sam Cooke , who was now very successful in the pop genre. On the one hand, Arden concealed from Little Richard that the European audience largely ignored his gospel records, on the other hand he made British fans believe that the musician was booked for a rock 'n' roll tour. When he started playing spiritual songs like I Believe and Peace in the Valley for his first show in October 1962 with the support of the young organist Billy Preston , the audience reacted disappointed and unwilling. So Little Richard and the accompanying musicians organized a spontaneous rock 'n' roll comeback , which was so enthusiastically celebrated that he went through the following tour entirely in the old genre and in the well-known production. Brian Epstein , the manager of the Beatles at the time , arranged some concerts with the band and Little Richard in northern England and a subsequent tour of Hamburg clubs.

On a second tour of England in mid-1963, for which Don Arden booked the Everly Brothers and Bo Diddley alongside Little Richard , the still almost unknown Rolling Stones were on the same stage. In his American homeland, his departure from music and the lifestyle of a clergyman initially went unnoticed. The longing for the life as a rock 'n' roll star and the earning opportunities that were brought before his eyes by the emerging success of the Beatles in America sealed his decision to return to rock music.

Comeback (1964–1977): soul and funk

With Bama Lama Bama Loo Little Richard started his studio comeback with his old label Specialty Records, which was reopened especially for the occasion. He tried to modify his rock 'n' roll sound, which was originally dominated by brass, in favor of a modern guitar arrangement. The single reached # 82 on the Billboard charts . The decision to present itself to the public again in the USA as the "King of Rock 'n' Roll" apparently came at an inopportune time, as music tastes had already changed in the mid-1960s: The rock 'n' roll des The past decade was about to be supplanted by the British Invasion , the main characters of which had been heavily influenced by Little Richard's work and style. Little Richard therefore made some effort to build on the old successes. He hired his former mentor Bumps Blackwell as a manager , added extras to his live band The Upsetters for an elaborate stage show called Crown Jewels and the Royal Guard , and toured extensively in the USA. In the phase of his comeback, his concerts were characterized by an opulence and self-expression that reached into the grotesque with regard to the show interludes and the play with roles and clichés of different sexual orientations.

The second station of his comeback after Specialty Records was the blues label Vee-Jay Records . The two official albums Little Richard is Back and Little Richard's Greatest Hits showed a further development of the sound in the direction of soul : prominent winds, in addition to the saxophones now also a horn section consisting of brass and the electronic organ , his new recordings of old specialty hits fit as well as some new titles to the public expectations of the 1960s. Between September 1964 and June 1965, the still little-known Jimi Hendrix was part of the entourage as a helper and guitarist, but was not tolerated for long due to his unreliability and Little Richard's dominance.

From the end of 1965 Little Richard was under contract with Modern Records for a few, but very productive months . Again there was a selection of new recordings of old hits in addition to new material. The first album Little Richard Sings His Greatest Hits - Recorded Live! should suggest a fast-paced live atmosphere through well-rehearsed applause and ventured into the funk sound with Do You Feel It . The second album The Wild and Frantic Little Richard combined more relaxed recordings of a live session with those from the studio. Together with a singer unknown by name, he recorded a duet for the first time with the Jimmy Reed classic Baby What You Want Me to Do , which was followed by more into the 2000s.

At the beginning of 1966, Little Richard moved to Okeh Records in New York. His two-year contract did not provide for a say in the selection of the pieces or in the arrangement. His former Specialty colleague Larry Williams was hired as the producer, and Johnny Guitar Watson was hired for the guitar . Little Richard was not involved in the compositions of the first album The Explosive Little Richard . With a dominant use of trumpets and a funky rhythm section, the musical strategy was maintained along the current black mainstream. For the second album Little Richard's Greatest Hits - Recorded Live! A small, enthusiastic audience was invited to the studio of Okeh's mother label CBS Records in Los Angeles, which has been converted into a virtual club Okeh . The sound of the new recordings of old hits corresponded to that of the previous album, plus a continuous rhythm arrangement and egocentric and euphoric interludes from the singer. Due to the lack of success, for which Little Richard made Larry Williams' Motown sound responsible, he only took three singles for Brunswick Records around the turn of the year 1967/1968 and let his contract with Okeh expire.

From 1970 to 1972 Little Richard celebrated the climax of his comeback at Reprise Records as part of the rock 'n' roll revival . Once again with Bumps Blackwell as manager and co-producer alongside well-known staff such as Jerry Wexler , Tom Dowd , H. B. Barnum and Quincy Jones at the studio mixers, he wanted to get back to the old sound of the 1950s with new songs. Some smaller chart successes with single releases of the three programmatically titled albums The Rill Thing ("The True Thing"), King of Rock And Roll ("King of Rock 'n' Roll '") and The Second Comin ("The Second Arrival") ). Since Little Richard did not renew his contract in August 1972, the fourth album Southern Child , enriched with country music elements , could not be released and was only released in 2005.

Although none of the releases of the period matched the innovative power and popularity of his major work from the 1950s, they also found worldwide buyers in the form of many re-releases , compilations and bootlegs . Chart placements in the important music markets on both sides of the Atlantic remained the exception. However, Little Richard was still a guarantee for sold out concert halls. Over the years he has appeared almost daily to American and European audiences, often in famous concert halls or at festivals alongside Chuck Berry , Jerry Lee Lewis and Bo Diddley . But he also played on the same stages with current greats such as Janis Joplin , John Lennon and Yoko Ono , from whom he often stole the show. To promote his concerts and publications, Richard was also a frequent guest on television shows with hosts Merv Griffin , Mike Douglas , Johnny Carson , Steve Allen and Dick Clark, among others .

Reprise was the last record label that Little Richard was under contract for a long time. This was followed by individual recordings for the small companies ALA Records, Greene Mountain, Manticore Records, Mainstream Records and Creole Records. Just a one-day session for Kent Records in January 1973 yielded enough material for the album Right Now, which was released by Kent's sister label United Records and could be considered a traditional reaction to the last, poorly selling, slightly more progressive reprise album The Second Coming . In addition, new live recordings of his greatest hits for S. J. Productions were released in the form of the concert documentary Let the Good Times Roll . From 1970, Little Richard appeared repeatedly as a guest musician with other artists, including Jefferson Starship , Delaney & Bonnie , the James Gang , Canned Heat and Bachman Turner Overdrive .

The second retreat (1977–1985): Gospel

As early as August 1972, Little Richard had received harsh reviews from the British press after a technically disastrous performance at London's Wembley Stadium . As the rock 'n' roll revival subsided, Little Richard played in front of empty houses on another tour of England. Even the record sales and chart notes had not met his expectations during the time of his comeback, so that the failures at the live performances brought Little Richard's artistic concept and its economic planning even more difficult. The exhausting concert tours and drug consumption also made health problems for him, so that he had to be hospitalized several times. With the renewed departure of his long-time mentor Bumps Blackwell in 1974, the problems developed into a personal crisis for the musician.

On January 1, 1977, the new management announced that Little Richard would renounce rock music for the second time and resume his work as a preacher. The reasons Little Richard gave for this withdrawal were similar to those in 1957: both his sexual orientation and life as a rock 'n' roll musician were incompatible with his religious beliefs. In retrospect, he justified his decision with various deaths, including the heart attack of his brother Horace "Tony" Penniman and Elvis Presley's death in August 1977. In March 1979 World Records released the gospel album God's Beautiful City in a very small edition .

Richard used the regular appearances on television shows for sermons and prayers with the audience, mostly musically formed by one or two of his gospel songs. In the early 1980s he worked with Bumps Blackwell and Charles “Dr. Rock “White on his biography The Quasar of Rock, in which he speaks very openly about his personal attitudes towards rock 'n' roll, homosexuality and racism , among other things . The book was published October 1, 1985 and provided for interest in the life and work of the artist, as a result Little Richard frequently on television, among other again at Merv Griffin and Johnny Carson, but also with David Letterman , Pat Robertson and Phil Donahue to was seen.

Rock 'n' Roll veteran (1985-2020): Pop-Rock

In the summer of 1985, Little Richard began to develop his acting career, which received little attention compared to his musical work. With Lifetime Friend he released a new gospel album with Warner Brothers . The sound corresponds to the pop decade of its creation. The single Great Gosh A'Mighty was able to place in the American and British charts. This was a success of his new management who tried to combine his Christian message concern with his pop ambitions. His next album Shake It All About with rock 'n' roll versions of popular nursery rhymes was released in 1992 by the Walt Disney Company record label and achieved platinum status . The album Little Richard Meets Takanaka followed from a collaboration with the Japanese rock guitarist Masayoshi Takanaka.

The beginning of the preparation of his work in the 1990s in the form of elaborate CD editions , each of which compiled the complete recording sessions on a label, as well as the frequent, good placements in the best lists at the turn of the century, aroused public interest in Little Richard's early work. By participating in the TV documentary Little Richard in 2000, in which the actor Leon Robinson reenacts scenes from his life, Little Richard gave further insights into his lively story. In the 1990s and 2000s he toured America and Europe again and again, often at the side of his old companions Jerry Lee Lewis and Chuck Berry , who presented themselves with a corresponding program as "Living Legends of Rock 'n' Roll". Little Richard was also occasionally heard as a guest musician, and he also recorded new titles for compilations and soundtracks . At the end of 2009 he underwent hip surgery.

After announcing his departure from the music business several times, the now eighty-year-old declared his final farewell in an interview with Rolling Stone in 2013 with the words: “I am done!” (“I'm done!”). After the end of his career he devoted himself more to religion. Little Richard died of complications from bone cancer at his Tennessee home on May 9, 2020, aged 87 . On May 20, Little Richard was privately interred in Oakwood University Memorial Gardens Cemetery , the cemetery of his former theological university in Huntsville , Alabama .

Musical style

Song structure and rhythm

The successful rock 'n' roll pieces Little Richards are strikingly similar in terms of structure, instrumentation and content. The basis of the compositions is mostly a 12-bar blues , which varies the main functions of harmony in three chords . In rhythm , the 4/4 time dominates, which is common in blues and swing and sets itself apart from the pieces of the competing pop industry of the 1950s with a clear backbeat . This rhythmic emphasis on the second and fourth beat of the bar is already established in rhythm and blues. The entire rhythm section necessarily emphasizes this “rockbeat” in order to be able to withstand Little Richard's volume on the microphone and the keys. When recording in New Orleans, Earl Palmer coupled the backbeat on drums with a swinging shuffle , that is, shifting the eighth notes to the next quarter.

The drummer Charles Connor developed the "Choo-Choo-Train" style during the studio recordings of Little Richards with the Upsetters in Los Angeles, in which the eighth notes are continuously struck between the quarters accentuated by the backbeat, which is supposed to resemble the pounding of a train. An example of this is the intro of Keep A Knockin ' from January 1957. Some slower blues ballads like I'm Just a Lonely Guy , Send Me Some Lovin' or Can't Believe You Wanna Leave have a relaxed 12/8 Use a beat typical of many New Orleans pianists. In the shuffle, the rock 'n' roll bass usually also plays a rolling eight-tone figuration, which is taken from boogie woogie and, due to its consistent harmonic assignment to the chord scheme, holds the songs together, especially when there are additional song structures in the Gospels or pop music vary the blues scheme.

Instrumentation and arrangement

While in rock 'n' roll the electric guitar often provides the new, aggressively noisy chordal sound, in Little Richard this stepped into the background, so that its task was taken over by an intense and dominant piano playing. The instrumentation of Little Richard's hits, with a prominent woodwind section, once again referred to the swing era that was coming to an end at that time. On the recordings from the J&M studio with Lee Allen and Alvin “Red” Tyler, at least two saxophonists can be heard throwing in polyphonic riffs that answer the vocal phrases. Lee Allen's tenor sax solos became an important hallmark of Little Richard's Specialty recordings due to the driving, glissanding, and roaring style. The Upsetters performed at concerts and recordings with up to four saxophonists. The vocal harmonic often used in rhythm and blues was largely missing, only on The Girl Can't Help It Little Richard is supported by a male vocal group. The third album The Fabulous Little Richard from 1959 also presented blues recordings that were provided by Specialty Records for subsequent publication during Little Richard's theological training with a female background choir using the overdub technique.

Piano playing

Little Richard's piano playing was characterized by the boogie-woogie and rhythm-and-blues style from New Orleans, which he performed particularly hard and quickly. He either imitated the bass run with his left hand in the function of a basso ostinato or varied forms of boogie-woogie in dotted chords. With his right hand Richard, on the other hand, usually hammered high, extremely fast chords in continuous eighth notes (eight-to-the-bar boogie) or in triplets. Especially with solos, Little Richard hit the high octaves of his piano, a playing style that provokes comparison with machine gun salvos. His producer Blackwell recalled a few times when bass strings snapped on the piano keyboard under Little Richard's pounding.

singing

The dense instrumental arrangement ensured - also due to the modest studio technology of the sound engineer Matassa - for a consistently high volume of the recordings. There was hardly any musical dynamic . The typical stop times are breaks in which the instruments only emphasize the first beat of a bar and otherwise remain silent, with the singer speaking or calling the text in rhythmic staccato rather than singing - as heard in Rip It Up, for example , She's Got It or Good Golly Miss Molly. Vocally, Little Richard was initially based on Roy Brown and other blues shouters of jump blues, who are differentiated from the crooners , the " potty singers " of pop music, because of their harder vocal style than belters . Within the belting he was also characterized by a very emotional and inspired style, which is why Arnold Shaw counts him more to the Emoters than to the pure Screamers .

One of his trademarks was the high falsetto “Whoooo!” That he had listened to from the gospel singer Marion Williams . Music journalist Nik Cohn describes Little Richard's singing as follows: “It screeched and screamed. His voice was freakish, tireless, hysterical and absolutely unbreakable. His singing was never lower than the roar of an angry bull. He garnished every phrase with whimpering, snarling or siren tones. His vitality and drive were limitless. ”In addition to these qualities as a rock 'n' roll singer, Robert Chambers attests to a broad stylistic spectrum:“ From the conventional tenor to gospel and delta blues to the elegant and controlled reminiscence of Nat King Cole ; Little Richard can sing everything. ”Especially in the phase of his comeback, Little Richard added long-lasting, textless melisms as song intros or heckling to his staccato .

Song content

The lyrics of the pieces suggest classic rock 'n' roll themes: sex and fun. While Little Richard's own compositions often tended to be coarse slippery and had to be defused by experienced lyricists for the recordings, other composers of his hits like to play with the ambiguities that the stock of terms in rock 'n' roll language provides. This is how the songwriter Dorothy La Bostrie formulates the first verse of Tutti Frutti :

|

|

The possible meaning of the English predicate to rock spans a rhythmic movement from dance to sexual intercourse. In addition to this love poetry, it is also about the young audience's need for fun and entertainment. This is what songwriter John Marascalco wrote in Rip It Up in 1956 :

|

|

Discography

Little Richard has recorded for at least 30 different record labels since 1951. A variety of compilations , re-releases, and bootlegs exist . The following album list therefore only contains the official album editions that were made during the contract periods with the record companies and that largely cover Little Richard's work. Compilations are missing.

- 1957 - Here's Little Richard , Specialty LP-100 or 2100

- 1958 - Little Richard , Specialty LP-2103

- 1959 - The Fabulous Little Richard , Specialty LP-2104

- 1960 - Pray Along with Little Richard, Vol. 1 , Golddisc LP-4001

- 1960 - Pray Along with Little Richard, Vol. 2 , Golddisc LP-4002

- 1961 - It's Real , Mercury MG-20656

- 1964 - Little Richard Is Back , Vee-Jay LP-1107

- 1964 - Little Richard's Greatest Hits , Vee-Jay LP-1124

- 1966 - Little Richard Sings His Greatest Hits - Recorded Live! , Modern-LP 1000

- 1967 - The Wild and Frantic Little Richard , Modern LP-1003

- 1967 - The Explosive Little Richard , Okeh LP-14117

- 1967 - Little Richard's Greatest Hits - Recorded Live! , Okeh LP-14121

- 1970 - The Rill Thing , Reprise LP-6406

- 1971 - The King of Rock 'n' Roll , Reprise LP-6462

- 1972 - The Second Coming , Reprise LP-2017

- 1972 - Southern Child , (unreleased recap recordings until 2005), Rhino Records

- 1974 - Right Now! , United LP-7791

- 1976 - Little Richard Live! , K-Tel LP-462

- 1979 - God's Beautiful City , World LP-1001

- 1986 Lifetime Friend , Warner Bros. 4-22529

- 1992 - Shake It All About , Disney 60849

- 1992 - Little Richard Meets Takanaka , TOCT 6619

Little Richard as an actor

Little Richard has appeared in front of the camera on several occasions throughout his career. He appeared in the 1956 film The Girl Can't Help It , to which he also contributed the title track, and in Don't Knock the Rock and in 1957 in Mister Rock and Roll as a musician. If these appearances in the 1950s can still be explained by the popularity of his music at the time, he began to take on roles on his second comeback in 1985. He played the Orvis Goodnight in Zoff in Beverly Hills in 1986 , the Mayor in Purple People Eater in 1988 and the Alphonso in Goddess of Love. In 1990 he starred as Old King Cole in Mother Goose Rock 'n' Rhyme, in 1991 as Brandon in Sunset Heat, in 1992 as Airborne Mustard Lover in The Naked Truth and in 1993 as President in The Pickle . In other films and television series he played himself or a rock musician in the form of small cameo appearances , namely in 1991 in the Columbo episode Columbo and the Murder of a Rock Star and in 1993 in Last Action Hero . He also appeared frequently in supporting roles in television series, including Miami Vice , Baywatch , Full House (Season 7, Episode 23) and Night Man. He was also available as an interview partner for film documentaries about rock musicians or played himself in real documentaries, including a 1973 film about Jimi Hendrix and 1998 in Why Do Fools Fall in Love about Frankie Lymon . In 1980 he stood in front of the camera for the documentary implementation of his previous career in the Little Richard Story . In 2003 he dubbed a cartoon character of himself in the episode Special Edna of the television series The Simpsons .

Achievements and Awards

Little Richard's chart placements focus on the US and UK markets. His singles Tutti Frutti, Long Tall Sally / Slippin 'And Slidin', Rip It Up / Ready Teddy, Lucille / Send Me Some Lovin, Jenny Jenny / Miss Ann, Keep A Knockin ' and Good Golly, sold over a million times Miss Molly gold status. Between 1955 and 1958 Little Richard had 18 chart hits. In addition to the chart successes and the resulting awards from the record industry, Little Richard was recognized for his work by well-known institutions and media in the music industry. He was among the first ten artists to be elected into the newly founded Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1986 , his induction into the Songwriters Hall of Fame followed in 2003, that into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2015. In 1990 he was Relocated in honor of a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame . In 1994 Richard received the Lifetime Achievement Pioneer Award from the Rhythm and Blues Foundation . The music magazine Rolling Stone lists Little Richard with Tutti Frutti, Long Tall Sally, Good Golly Miss Molly, The Girl Can't Help It and Keep A Knockin ' five times in its popular list of the 500 best songs of all time . His specialty records debut album Here's Little Richard made it to 50th place on the list of the 500 best albums of all time . In the choice of 365 Songs of the Century , Tutti Frutti placed 130th. Rolling Stone also listed Little Richard eighth of the 100 greatest musicians and twelfth of the 100 best singers of all time .

effect

American literary scholar David Kirby laments Little Richard in his 2010 book . The Birth of Rock 'n' Roll, Little Richard's low presence in music journalism, would not correspond to its actual musical and cultural importance. Although Little Richard had an extroverted stage image, he was hardly interested in professional self-marketing , so that he was difficult to capture in public appreciation. Other musicians, however, left no doubt about Little Richards' great influence on their work.

Musical effect

The music magazine Rolling Stone leads Little Richard in its "List of the 100 greatest artists of all time" from 2004 in eighth place. At least six of the better placed musicians confirm the strong influence that Little Richard and his music had on their work and thus on the development of rock music as a whole. While Little Richard himself was still an imitator of the rhythm and blues shouters popular in the black music market in his early work phase at RCA and Peacock, he developed his own style with Tutti Frutti for the first recording session for Specialty Records, which is characteristic of the young rock genre was 'n' roll .

The first important characteristic is the simplicity of the songs, which, in their deliberate simplicity, largely elude music-theoretical analysis due to their ineffectiveness. In Little Richard's repertoire, Nik Cohn makes “total non-songs, [...] without melody, without text” and intensifies his thesis to such an extent that he uses Tutti Frutti's scat intro “AWopBopALooBopALopBamBoom” as the “denominator of pop music” identified in 1956. In 2007, prominent musicians voted Tutti Frutti in the music magazine Mojo as the record that changed the world the most. However, if Little Richard's success cannot be justified with original and complex songwriting, the core of the artistic expression must be the performance itself, that is, the "sound" presented on sound carriers and during performances as the second important characteristic of his music. Little Richard's original singing style emerges, which many of his followers from rock 'n' roll and rock music praised or sought to adopt : John Lennon and Paul McCartney , who took over Richard's “Woooh!” On their 1963 tour, and Ian Gillan , Mitch Ryder , Screaming Lord Sutch , Neil Young , Ry Cooder and many more. Even instrumentalists emulated Little Richard's voice, such as Jimi Hendrix with his guitar.

With the constant change between rock 'n' roll and gospel, the third characteristic of Little Richard's music is the emotionality and religious fervor of expression. Religious music was widespread through gospel and spiritual groups, but the popularization and the connection with the secular content and stylistic devices of rock music was just being carried out for the first time at the end of the 1950s by a few musicians like Ray Charles . While Arnold Shaw speaks of "gospel blues" in this context in the retrospective, Quincy Jones, as arranger of the Mercury recordings, attested Little Richards to "rock 'n' soul" and thus traced a parallel development of black pop music to mainstream rock 'n' roll as soul and later funk .

Some of the important representatives of soul such as James Brown , Otis Redding or Sam Cooke are the direct successors of Little Richard and benefited from working with him at the beginning of their careers. The original soul as a link between rock and gospel can be best traced in Little Richard's biography. However, he lagged behind his former emulators in his own musical development during his comeback in terms of innovation and commercial success. His self-perception, driven by religious convictions, remains unaffected by this: “I call it music that heals. […] The music that makes the blind see, the lame, the deaf and the mute walk, hear and speak! The music of joy, the music that makes your soul soar. Yes, yes, because I am the living flame and Little Richard is my name ... "

Effect on the American music market

In the mid-1950s, the American music market was dominated by the pop music of Tin Pan Alley , in which composers and publishers produced their professionally arranged songs with as many established entertainers as possible for the white bourgeoisie. In addition, there were divisional markets for country music and black rhythm and blues , which was previously also known as race music , each with their own music labels , charts , record stores, radio stations and audiences. If a title was successful in a genre, a defused cover version in the pop sound was often played by an established crooner , and more rarely the other way around. Little Richard's recordings for Specialty Records quickly caught the attention of the major labels operating in the pop market . Pat Boone in particular covered Tutti Frutti in a timely manner in 1955 and was able to sell considerably more records thanks to the greater marketing opportunities the pop market had. With the follow-up cover Long Tall Sally this was no longer possible in 1957, which indicates a shift within the segregated music markets. Little Richard had managed the crossover into the pop market.

In the meantime, rock 'n' roll had established itself as the music of the younger generation, who recognized the youth-friendly content and danceable rhythms as a suitable form of expression for their attitude towards life. New technical production and marketing methods as well as the development of the mass media cinema, television and portable radio sets contributed to this development. The black original also seemed more attractive to the white teenager than the boring cover arrangement of the pop performers. This development was promoted by radio DJs like Alan Freed , who also coined and popularized the name of the new cross-racial genre "Rock 'n' Roll".

Little Richard himself was always ambivalent about the racially segregated music market. On the one hand he welcomed the enthusiasm of his white fans and negated the importance of skin color for the music, on the other hand he complained with clear words both about the still latent racist structures in the pop industry and about their black counter-movement in the area of soul music, as his Comeback failed in the 1960s and 1970s in terms of lack of chart success. The debate about the crossover - gain in economic and musical freedom on the one hand and loss of identity and latent exploitation on the other - becomes particularly clear in Little Richard's work and biography. At a hearing before the United States Congress on September 20, 1984 to clarify the exploitation of African American artists by the music industry, Little Richard claimed to have overcome these racial barriers in the 1950s. Especially in his early rock 'n' roll work phase, Little Richard made a decisive contribution to the rapprochement of the various music markets, not only through his own recordings, but also through the large number of cover versions: especially the young English beat groups of the British Invasion filled their repertoires in the 1960s with Little Richard songs. Many rock and hard rock musicians of the later decades also re-introduced Little Richard's standards.

Influences on the show aspect of rock music

In the American music market of the 1950s and 1960s, African American musicians like James Brown and Nat King Cole were exposed to racist hostility from the white audience with sexually charged performances. Little Richard and his early management therefore deliberately developed the exaggeratedly crazy image of a freak and "King of Rock 'n' Roll". When asked about the other popular "King" Elvis Presley , Richard gladly dodged the title "Queen of Rock 'n' Roll" and opened up elements of travesty for himself and his stage presence , which he had developed in the course of his own homosexual experiences since early youth and had cultivated. The male, white public feared no rivalry from him. These craziness included the wildness of his performances, including energetic and artistic interludes on and on the piano, striptease and intense audience contact, but also unusual stage outfits such as royal robes, mirrored suits and feminine costumes.

While his personal and general statements and assessments of homosexuality were always ambivalent , his pioneering work in this regard was of great importance for later rock music artists, especially those of glam rock : Sylvester James as well as Elton John and David Bowie pose themselves in Little Richard's successor. While Mick Jagger , Marc Bolan and Freddie Mercury still encountered social reservations when they acquired an androgynous extroversion based on Little Richard's model in the 1970s, it was easier for other African-American musicians such as Prince and Michael Jackson to appear in the 1980s. The music journalist Olaf Karnik sees one reason for this in the minstrel tradition, which downplayed the black entertainer as a comedic show object. This " gender - bending " (about stretching of gender ), which in the tradition of dandyism and the camp is -Aesthetics, has now become an integral part of the expression in the musical show and was in the 2000s by artists such as Andre 3000 embodying .

literature

- John Garodkin: Little Richard Special . 2nd Edition. Mjoelner Edition, Praestoe 1984, ISBN 87-87721-14-7 .

- David Kirby: Little Richard. The Birth of Rock 'n' Roll . 1st edition. Continuum, New York 2009, ISBN 978-0-8264-2965-0 .

- Paul MacPhail: Little Richard: The Originator of Rock . Self-published, 2008.

- Charles White: The Life and Times of Little Richard. The Authorized Biography . Omnibus Press, London / New York / Paris / Sydney / Copenhagen / Berlin / Madrid / Tokyo 2003, ISBN 0-7119-9761-6 (first edition: 1984).

Film documentaries

- William Klein : The Little Richard Story , 1980.

- Bill Hinton: South Bank Show , 1985 (distributed irregularly as Little Richard Documentary ).

- Robert Townsend : The Little Richard Story , 2000 ( Little Richard ).

Web links

- Little Richard at Allmusic (English)

- Little Richard in the Internet Movie Database (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c d Charles White: The Life and Times of Little Richard. The Authorized Biography . Omnibus Press, London / New York / Paris / Sydney / Copenhagen / Berlin / Madrid / Tokyo 2003, ISBN 0-7119-9761-6 , The Georgia Peach, pp. 3-19 (First edition: 1984, many publications also mention 1935 as the date of birth. In Little Richard's biography, his mother Leava Mae Penniman is cited as December 5, 1932).

- ↑ Lee Hildebrand: Here's Little Richard . Specialty Records, Beverly Hills 2011 (CD booklet of the 2011 reissue of Little Richard's first album Here's Little Richard ).

- ↑ a b David Kirby: Little Richard. The Birth of Rock 'n' Roll . 1st edition. Continuum, New York 2009, ISBN 978-0-8264-2965-0 , Chapter 2: The Ninety-Nine Names of the Prophet, pp. 63-97 (American English).

- ^ Charles White: The Life and Times of Little Richard. The Authorized Biography . Omnibus Press, London / New York / Paris / Sydney / Copenhagen / Berlin / Madrid / Tokyo 2003, ISBN 0-7119-9761-6 , Thinkin 'About My Mother, pp. 34-42 (first edition: 1984).

- ^ A b c d Charles White: The Life and Times of Little Richard. The Authorized Biography . Omnibus Press, London / New York / Paris / Sydney / Copenhagen / Berlin / Madrid / Tokyo 2003, ISBN 0-7119-9761-6 , Tutti Frutti, p. 55-79 (first edition: 1984).

- ^ Charles White: The Life and Times of Little Richard. The Authorized Biography . Omnibus Press, London / New York / Paris / Sydney / Copenhagen / Berlin / Madrid / Tokyo 2003, ISBN 0-7119-9761-6 , Recording Sessions, pp. 235-262 (first edition: 1984).

- ↑ a b c John Garodkin: Little Richard Special . 2nd Edition. Mjoelner Edition, Praestoe 1984, ISBN 87-87721-14-7 , Specialty Records, pp. 23-66 .

- ^ A b Charles White: The Life and Times of Little Richard. The Authorized Biography . Omnibus Press, London / New York / Paris / Sydney / Copenhagen / Berlin / Madrid / Tokyo 2003, ISBN 0-7119-9761-6 , Don't Knock The Rock, pp. 80-95 (first edition: 1984).

- ^ A b c Charles White: The Life and Times of Little Richard. The Authorized Biography . Omnibus Press, London / New York / Paris / Sydney / Copenhagen / Berlin / Madrid / Tokyo 2003, ISBN 0-7119-9761-6 , The Most I Can Offer, pp. 96-107 (first edition: 1984).

- ^ A b c d Charles White: The Life and Times of Little Richard. The Authorized Biography . Omnibus Press, London / New York / Paris / Sydney / Copenhagen / Berlin / Madrid / Tokyo 2003, ISBN 0-7119-9761-6 , I'm Back, p. 111-121 (first edition: 1984).

- ↑ a b James E. Perone: Mods, Rockers, and the Music of the British Invasion . Greenwood Publishing Group, Westport 2009, ISBN 978-0-275-99860-8 , 1960-1963: From the Rocker Aesthetic to the Mod Aesthetic, pp. 35-75 .

- ↑ a b c d e Charles White: The Life and Times of Little Richard. The Authorized Biography . Omnibus Press, London / New York / Paris / Sydney / Copenhagen / Berlin / Madrid / Tokyo 2003, ISBN 0-7119-9761-6 , The King Of Rock 'n' Roll, pp. 122-144 (first edition: 1984).

- ↑ John Garodkin: Little Richard Special . 2nd Edition. Mjoelner Edition, Praestoe 1984, ISBN 87-87721-14-7 , Vee-Jay Records, pp. 83-104 .

- ↑ Harry Shapiro, Caesar Glebbeek: Jimi Hendrix. Electric Gypsy. The biography . 1st edition. vgs verlagsgesellschaft, Cologne 1993, ISBN 3-8025-2243-5 , p. 100 f . (English: Jimi Hendrix - electric gypsy . Translated by Ingeborg Schober).

- ↑ John Garodkin: Little Richard Special . 2nd Edition. Mjoelner Edition, Praestoe 1984, ISBN 87-87721-14-7 , Modern Records, pp. 106-113 .

- ↑ Ken Harris: Little Richard. Greatest hits. In: RollingStone.com. July 26, 1969, archived from the original on December 8, 2007 ; Retrieved on May 11, 2020 (the review of the album is on the Rolling Stone homepage under the wrong title and cover).

- ↑ John Garodkin: Little Richard Special . 2nd Edition. Mjoelner Edition, Praestoe 1984, ISBN 87-87721-14-7 , OKeh Records, p. 115-122 .

- ↑ John Garodkin: Little Richard Special . 2nd Edition. Mjoelner Edition, Praestoe 1984, ISBN 87-87721-14-7 , Reprise Records, pp. 127-134 .

- ↑ John Broven: Record Makers and Breakers. Voices of the Independent Rock 'n' Roll Pioneers . University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Chicago 2010, ISBN 978-0-252-03290-5 , Art Rupe: Specialty Records, pp. 304-306 (American English).

- ↑ John Garodkin: Little Richard Special . 2nd Edition. Mjoelner Edition, Praestoe 1984, ISBN 87-87721-14-7 , Kent Records, pp. 143 .

- ^ A b Charles White: The Life and Times of Little Richard. The Authorized Biography . Omnibus Press, London / New York / Paris / Sydney / Copenhagen / Berlin / Madrid / Tokyo 2003, ISBN 0-7119-9761-6 , Slippin 'And Slidin', pp. 165-179 (first edition: 1984).

- ^ A b Charles White: The Life and Times of Little Richard. The Authorized Biography . Omnibus Press, London / New York / Paris / Sydney / Copenhagen / Berlin / Madrid / Tokyo 2003, ISBN 0-7119-9761-6 , From Rock 'n' Roll to the Rock of Ages, pp. 203-214 (first edition: 1984).

- ^ A b c Paul MacPhail: Little Richard. The Originator Of Rock . 2008, p. 94 ff .

- ^ Paul MacPhail: Little Richard. The Originator of Rock . Self-published, 2008, p. 97 .

- ↑ Stephen Holden: Ooh! My soul . In: The New York Times . October 14, 1984 (American English, online [accessed May 11, 2020]).

- ↑ Little Richard. Billboard Singles at Allmusic (English). Retrieved May 11, 2020 (originally published in Billboard Magazine, multi-author database).

- ↑ UK Top 40 Hit Database. In: everyHit.com. Retrieved on May 11, 2020 (English, database maintained by several authors, “Little Richard” as search input under “Name of Artist”).

- ^ Charles White: The Life and Times of Little Richard. The Authorized Biography . Omnibus Press, London / New York / Paris / Sydney / Copenhagen / Berlin / Madrid / Tokyo 2003, ISBN 0-7119-9761-6 , Postscript - Lifetime Friend, pp. 215-226 (first edition: 1984).

- ↑ Little Richard has had hip surgery. Augsburger Allgemeine , December 3, 2009, accessed on May 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Little Richard Announces Retirement: 'I Am Done'. In: Ultimate Classic Rock. 2013, accessed on May 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Little Richard - the rock 'n' roller turns 85. Salzburger Nachrichten , December 5, 2017, accessed on May 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Tim Weiner: Little Richard, Flamboyant Wild Man of Rock 'n' Roll, Dies at 87th The New York Times , May 9, 2020, accessed May 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Little Richard Rock 'n' Roll Legend Laid to Rest. In: tmz.com. May 20, 2020, accessed on May 22, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Tony Scherman: Beackbeat. Earl Palmer's Story . Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington / London 1999, ISBN 1-56098-844-4 , pp. 89-91 .

- ↑ a b Arnold Shaw: Rock 'n' Roll. The stars, the music and the myths of the 50s . 1st edition. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1978, ISBN 3-499-17109-0 , p. 97 (American English: The Rockin '50s . 1974. Translated by Teja Schwaner).

- ↑ Charles Connor Biography.( Memento from September 20, 2008 in the Internet Archive ). Charles Connor's official homepage, accessed May 11, 2020.

- ↑ Nik Cohn: AWopBopaLooBopALopBamBoom . Piper, Schott, Munich / Mainz 1995, ISBN 3-492-18402-2 , p. 11 (English: Pop from the Beginning . 1969. Translated by Teja Schwaner).

- ↑ Billy Vera: Remembering Lee Allen. ( Memento of January 22, 2004 in the Internet Archive ). "Allen was a very important member of the studio band at Cosimo's. His solos appeard on hundreds of Crescent City classics. In 1958, Allen also recorded his own instrumental record on Ember titled “Walking With Mr. Lee” which charted # 54. However, it was his hard-driving solos on Little Richard and Fats Domino hits that inspired a new generation of sax players in the 1950s and 1960s. His unique and distinctive tone is still respected and often copied to this day. Allen's use of note bending and the "growl" technique were key factors in his style. "

- ^ A b Dörte Hartwich-Wiechell: Pop-Musik. Analyzes and interpretations . Hans Gerig KG, Cologne 1974, ISBN 3-87252-078-4 , Rock 'n' Roll, p. 64-72 .

- ↑ Eric Starr: The Everything Rock & Blues Piano Book . Adams Media, Cincinnati 2007, ISBN 978-1-59869-260-0 , Little Richard, pp. 192-194 .

- ^ A b Robert Chalmers: Legend: Little Richard . In: CQ . October 2010 (English, online ( memento of June 13, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) [accessed on May 11, 2020]).

- ↑ Arnold Shaw: Rock 'n' Roll. The stars, the music and the myths of the 50s . 1st edition. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek near Hamburg 1978, ISBN 3-499-17109-0 , The Beats and the Belters. Howl !, p. 67–68 (American English: The Rockin '' 50s . 1974. Translated by Teja Schwaner).

- ↑ a b Nik Cohn: AWopBopaLooBopALopBamBoom . Piper, Schott, Munich / Mainz 1995, ISBN 3-492-18402-2 , Klassischer Rock, p. 32–52 (English: Pop from the Beginning . 1969. Translated by Teja Schwaner).

- ^ Charles White: The Life and Times of Little Richard. The Authorized Biography . Omnibus Press, London / New York / Paris / Sydney / Copenhagen / Berlin / Madrid / Tokyo 2003, ISBN 0-7119-9761-6 , Awop-Bop-A-Loo-Mop Alop-Bam-Boom, p. 43-51 (first edition: 1984).

- ↑ Nick Tosches: Unsung Heroes of Rock 'n' Roll . Da Capo Press, New York 1999, ISBN 0-306-80891-9 , Introduction, pp. 1-11 (first edition: 1984).

- ↑ Little Richard. In: IMDb The Internet Movie Database. Retrieved on May 11, 2020 (English, database maintained by various authors).

- ^ Paul MacPhail: Little Richard: The Originator Of Rock . Self-published, 2008, p. 110 ff .

- ↑ Little Richard. In: Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved May 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Little Richard. In: Songwriters Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on August 21, 2008 ; accessed on May 11, 2020 (English).

- ↑ Little Richard. In: blues.org. Retrieved May 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Little Richard. In: walkoffame.com. Retrieved May 11, 2020 .

- ^ Pioneer Awards. In: Rhythm & Blues Foundation. Archived from the original on January 30, 2011 ; accessed on May 11, 2020 (English).

- ↑ The RS 500 Greatest Songs of All Time. In: Rolling Stone. December 9, 2004, pp. 1-5 , archived from the original on June 26, 2008 ; accessed on May 11, 2020 (English).

- ^ The RS 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. In: Rolling Stone. November 18, 2003, pp. 1–5 , accessed on May 11, 2020 (English).

- ^ Songs of the Century. In: archives.cnn.com. March 7, 2001, archived from the original on January 5, 2010 ; accessed on May 11, 2020 (English).

- ↑ 100 Greatest Artists of All Time. Rolling Stone , December 2, 2010, accessed May 11, 2020 .

- ↑ 100 Greatest Singers of All Time. Rolling Stone , December 2, 2010, accessed May 11, 2020 .

- ↑ David Kirby: Little Richard. The Birth of Rock 'n' Roll . 1st edition. Continuum, New York 2009, ISBN 978-0-8264-2965-0 , Introduction, pp. 1-25 .

- ↑ Little Richard: The Immortals - The Greatest Artists of All Time: 8) Little Richard. In: RollingStone.com. April 15, 2004, archived from the original on July 24, 2008 ; accessed on May 11, 2020 (English).

- ↑ a b Peter Wicke: Rock Music. Culture, Aesthetics and Sociology . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1993, ISBN 0-521-39914-9 , 'Roll Over Beethoven': new experiences in art, p. 1–27 (English, German: rock music: on the aesthetics and sociology of a mass medium . Berlin 1986. Translated by Rachel Fogg, first edition: 1987).

- ↑ Nik Cohn: AWopBopaLooBopALopBamBoom . Piper, Schott, Munich, Mainz 1995, ISBN 3-492-18402-2 , pp. 250 (English: Pop from the Beginning . 1969. Translated by Teja Schwaner).

- ↑ 100 Records That Changed The World. In: Rocklist.net. June 2007, accessed on May 11, 2020 (English, various music lists, originally published in Mojo Magazine, including "100 Records That Changed the World").

- ^ A b c Charles White: The Life and Times of Little Richard. The Authorized Biography . Omnibus Press, London / New York / Paris / Sydney / Copenhagen / Berlin / Madrid / Tokyo 2003, ISBN 0-7119-9761-6 , Testimonials, pp. 227-231 (first edition: 1984).

- ↑ a b Arnold Shaw: Rock 'n' Roll. The stars, the music and the myths of the 50s . 1st edition. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1978, ISBN 3-499-17109-0 , Teenage-Ausbruch, p. 171–173 (American English: The Rockin '' 50s . 1974. Translated by Teja Schwaner).

- ^ Arnold Shaw: Black Popular Music in America. From the Spirituals, Minstrels and Ragtime to Soul, Disco and Hip-Hop . Schirmer Books, New York 1986, ISBN 978-0-02-872310-5 , Black Is Beautiful, pp. 209-248 (English).

- ↑ Arnold Shaw: Rock 'n' Roll. The stars, the music and the myths of the 50s . 1st edition. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1978, ISBN 3-499-17109-0 , end of an era. Tin Pan Alley 1950–1953, pp. 23–79 (American English: The Rockin '' 50s . 1974. Translated by Teja Schwaner).

- ^ Charles Hamm: Putting Popular Music in it's Place . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1995, ISBN 0-521-47198-2 , Some Thoughts on the Measurement of Popularity in Music, pp. 116-130 (English).

- ↑ Reinhard Flender, Hermann Rauhe: Pop Music. Aspects of their history, functions, effects and aesthetics . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1989, Rock 'n' Roll revolutionizes pop music, p. 84-98 .

- ↑ Nelson George: The Death of Rhythm & Blues . Hannibal, Vienna 1990, ISBN 3-85445-051-6 , Der neue Schwarze (1950–1965), pp. 79–120 (American English: The Death of Rhythm & Blues . Translated by Lore Boas).

- ↑ a b Reebee Garofalo: Black Popular Music: Crossing Over or going under? In: Tony Bennett, Simon Fritt, Lawrence Grossberg, John Sheperd, Greame Turner (Eds.): Rock and Popular Music. Politics, Policies, Institutions . Routledge, New York 1993, ISBN 0-415-06368-X , pp. 231-248 (English).

- ↑ John Garodkin: The Influence of Little Richard . 1st edition. Garodkin Productions, Praestoe 1995 (English).

- ↑ Bruce Vilanch: The gay race card. In: The Advocate (p. 57). April 1, 1997, accessed May 11, 2020 .

- ^ A b Charlie Gillett: The Sound of the City. The history of rock music . 1st edition. Two thousand and one, Frankfurt am Main 1978, five styles of rock 'n' roll. II, p. 47–50 (American English: The Sound of the City . Translated by Teja Schwaner).

- ↑ Hanspeter Künzler: Just don't count as gay. Rap, reggae and homophobia - an inevitable combination? In: NZZ online. Neue Zürcher Zeitung, June 28, 2001, accessed on May 11, 2020 .

- ^ A b Nathan G. Tipton: Sylvester. ( Memento from April 11, 2014 in the Internet Archive ). At: glbtq.com. An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture. 2002, accessed on May 11, 2020.

- ↑ Stella Bruzzi: Mannish Girl. kd lang - from Cowpunk to Androgyny . In: Sheila Whiteley (Ed.): Sexing the Groove. Popular Music and Gender . Routledge, London / New York 1997, ISBN 0-415-14671-2 , pp. 191-206 (English).

- ↑ Olaf Karnik: Black Superstars: Success has no more color. Michael Jackson, Prince, Whitney Houston . In: Gerald Hündgen (Ed.): Chasin 'a Dream. The music of black America from soul to hip-hop . Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-462-01951-1 , p. 251-259 .

- ↑ Gina Vivinetto: Rocking our world. Prince and the evolution. In: St. Petersburg Times Online. April 29, 2004, archived from the original on December 3, 2013 ; accessed on May 11, 2020 (English).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Little Richard |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Penniman, Richard Wayne (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American rock 'n' roll musician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 5, 1932 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Macon , Georgia , USA |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 9, 2020 |

| Place of death | Tullahoma , Tennessee |