Socialism

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

Socialism refers to a broad array of movements and ideologies which aim to improve society through collective action and to a socio-economic system in which property and the distribution of wealth are subject to control by the community.[1] This control may be either direct—exercised through popular collectives such as workers' councils—or indirect—exercised on behalf of the people by the state. As an economic system, socialism is often characterized by state or worker ownership of the means of production.

The modern socialist movement had its origin largely in the working class movement of the 19th century. The Industrial Revolution had brought many economic and social changes. Factory owners became very wealthy, while long hours and impoverishment faced the factory workers.[2] Socialists criticised the suffering and injustices resulting from the concentration of property in the hands of the capitalist class.

Socialists have differed in their vision of socialism as a system of economic organization. Some socialists have championed the complete nationalization of the means of production, while social democrats have proposed selective nationalization of key industries within the framework of mixed economies. Some argued that the 1945 post-war socialist governments had abolished capitalism and that socialism was the practice of socialist government,[3] while others have supported nationalising the "commanding heights" of the economy under democractic workers' control.[4]

Some Marxists, including those inspired by the Soviet model of economic development, have advocated the creation of centrally planned economies directed by a state that owns all the means of production. Others, including Communists in Yugoslavia in the 1960s and Hungary in the 1970s and 1980s, Chinese Communists since the reform era, and some Western economists, have proposed various forms of market socialism, attempting to reconcile cooperative or state ownership of the means of production with market forces, which guide production and exchange in place of central planners.[5]

Anarcho-syndicalists and some elements of the U.S. New Left favor decentralized collective ownership in the form of cooperatives or workers' councils. Others may advocate different arrangements.

The Socialist International, the affiliate body for most of the world's social democratic parties, such as the Socialist Party of France, describes socialism as "an international movement for freedom, social justice and solidarity"[6]

Historical precedents

In the history of political thought, certain elements of a socialist or communist outlook long predate the socialism that emerged in the first half of the 19th Century. For instance, Plato's Republic and Thomas More's Utopia have been cited.[7] The 5th century Mazdak movement in what is now Iran has been described as "communistic" for challenging the enormous privileges of the noble classes and the clergy and striving for an egalitarian society.[8] William Morris considered that John Ball, one of the leaders of the Peasants' Revolt in England in 1381, was the first socialist.[9]

During the English Civil War in the mid 17th Century, movements identified with the socialist tradition include the levellers and the diggers, the latter believing that land should be held in common.

During the 18th-century Enlightenment, criticism of inequality appeared in the work of political theorists such as Jean Jacques Rousseau in France, whose Social Contract famously began, "Man is born free, and he is everywhere in chains."[10] Following the French Revolution of 1789, François Noël Babeuf espoused the goals of common ownership of land and total economic and political equality among citizens.

Origins of socialism

See also: History of Socialism

The appearance of the term "socialism" is variously attributed to Pierre Leroux in 1834,[11] or to Marie Roch Louis Reybaud in France, or else in England to Robert Owen, who is considered the father of the cooperative movement.[12]

The first modern socialists were early 19th century Western European social critics. In this period, socialism emerged from a diverse array of doctrines and social experiments associated primarily with British and French thinkers—especially Robert Owen, Charles Fourier, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Louis Blanc, and Saint-Simon. These social critics criticised the excesses of poverty and inequality of the Industrial Revolution, and advocated reforms such as the egalitarian distribution of wealth and the transformation of society into small communities in which private property was to be abolished. Outlining principles for the reorganization of society along collectivist lines, Saint-Simon and Owen sought to build socialism on the foundations of planned, utopian communities.

According to some accounts, the use of the words "socialism" or "communism" was related to the perceived attitude toward religion in a given culture. In Europe, "communism" was considered to be the more atheistic of the two. In England, however, that sounded too close to communion with Catholic overtones; hence atheists preferred to call themselves socialists.[13]

By 1847, according to Frederick Engels, "Socialism" was "respectable" on the continent of Europe, while "Communism" was the opposite; the Owenites in England and the Fourierists in France were considered Socialists, while working class movements which "proclaimed the necessity of total social change" termed themselves "Communists". This latter was "powerful enough" to produce the communism of Étienne Cabet in France and Wilhelm Weitling in Germany.[14]

Saint-Simon

Saint Simon, who is called the founder of French socialism, argued that a brotherhood of man must accompany the scientific organization of industry and society. He proposed that production and distribution be carried out by the state, and that allowing everyone to have equal opportunity to develop their talents would lead to social harmony, and the state could be virtually eliminated. "Rule over men would be replaced by the administration of things."[15]

Robert Owen

Robert Owen advocated the transformation of society into small, local collectives without such elaborate systems of social organization. Owen was mill manager from 1800-1825. He transformed life in the village of New Lanark with ideas and opportunities which were at least a hundred years ahead of their time. Child labour and corporal punishment were abolished, and villagers were provided with decent homes, schools and evening classes, free health care, and affordable food.[16]

The Factory Act of 1833 attempted to reduce, in just one industry, the textile industry, the hours adults and children worked. The working day was to start at 5.30 a.m. and cease at 8.30 p.m, but children of nine to thirteen years should work only 9 hours, and those of a younger age were prohibited. There were, however, only four factory inspectors, and this law was broken by the factory owners.[17] In the same year Owen stated:

Eight hours' daily labour is enough for any [adult] human being, and under proper arrangements sufficient to afford an ample supply of food, raiment and shelter, or the necessaries and comforts of life, and for the remainder of his time, every person is entitled to education, recreation and sleep.[18]

In a Paper Dedicated to the Governments of Great Britain, Austria, Russia, France, Prussia and the United States of America, Owen wrote: "The lowest stage of humanity is experienced when the individual must labour for a small pittance of wages from others."[19]

Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon pronounced that "Property is theft" and that socialism was "every aspiration towards the amelioration of society". Proudhon termed himself an anarchist and proposed that free association of individuals should replace the coercive state.[20][21] Proudhon, Benjamin Tucker, and others developed these ideas in a free-market direction, while Mikhail Bakunin, Piotr Kropotkin, and others adapted Proudhon's ideas in a more conventionally socialist direction.

In a letter to Marx in 1846, Proudhon wrote:

I myself put the problem in this way: to bring about the return to society, by an economic combination, of the wealth which was withdrawn from society by another economic combination. In other words, through Political Economy to turn the theory of Property against Property in such a way as to engender what you German socialists call community and what I will limit myself for the moment to calling liberty or equality.

Bakunin

Bakunin, the father of modern anarchism, was a libertarian socialist, a theory by which the workers would directly manage the means of production through their own productive associations. There would be "equal means of subsistence, support, education, and opportunity for every child, boy or girl, until maturity, and equal resources and facilities in adulthood to create his own well-being by his own labor."[22]

While many socialists emphasized the gradual transformation of society, most notably through the foundation of small, utopian communities, a growing number of socialists became disillusioned with the viability of this approach and instead emphasized direct political action. Early socialists were united, however, in their desire for a society based on cooperation rather than competition.

Marxism and the socialist movement

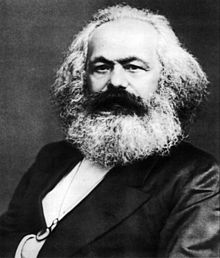

In 1848, Karl Marx and Frederick Engels published the Communist Manifesto. Marx and Engels drew from the socialist or communist ideas born in the French Revolution of 1789, the German philosophy of GWF Hegel, and English political economy, particularly that of Adam Smith and David Ricardo. Marx and Engels developed a body of ideas which they called scientific socialism, more commonly called Marxism.

The Communist Manifesto says "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles" [23] and famously declared that the working class would be the "grave digger" of the capitalist class.

Marx and Engels distinguished their scientific socialism from what they termed the utopian socialism of some other socialist trends. For Marxists, socialism or, as Marx termed it, the first phase of communist society, can be viewed as a transitional stage characterized by common or state ownership of the means of production under democratic workers' control and management, which Engels argued was beginning to be realised in the Paris Commune of 1871, before it was overthrown.[24] They see this stage in history as a transition between capitalism and the "higher phase of communist society" in which human beings no longer suffer from alienation and "all the springs of co-operative wealth flow more abundantly." Here "society inscribe[s} on its banners: From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs!" [25] For Marx, a communist society entails the absence of differing social classes and thus the end of class warfare. According to Marx and Engels, once a socialist society had been ushered in, the state would begin to "wither away", [26] and humanity would be in control of its own destiny for the first time. [27]

Marx and Engels argued that capitalism "compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production" [28] and raised the seminal call, "Proletarians of all countries, unite".[29]

The International Workingmen's Association - the First International

In 1864, the International Workingmen's Association or First International, was founded in London. Victor Le Lubez, a 30-year-old French radical republican living in London, invited Marx to come "as a representative of German workers" according to Saul Padover.[30] It held a preliminary conference in 1865 and its first congress at Geneva in 1866. Marx was appointed a member of the committee, and, according to Padover, Marx and Johann Georg Eccarius, a tailor living in London, were to become "the two mainstays of the International from its inception to its end." The First International became the first major international forum for the promulgation of socialist ideas.

The Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany, today known as the German Social Democratic Party (SPD), was founded in 1869. Socialism became increasingly associated with newly formed trade unions. In Germany the SPD built trade unions, and in Austria, France, and other European countries, socialist parties and anarchists played a prominent role in forming and building up trade unions, especially from the 1870s onwards. This stood in contrast to the British experience, where moderate New Model Unions dominated the union movement from the mid-nineteenth century and where trade Unionism was stronger than the political labour movement until the formation and growth of the Labour Party in the early years of the twentieth century.

Socialist groups supported diverse views of socialism, from the gradualism of many trade unionists to the radical, revolutionary theory of Marx and Engels. Anarchists and proponents of other alternative visions of socialism, who emphasized the potential of small-scale communities and agrarianism, coexisted with the more influential currents of Marxism and social democracy. The anarchists, led by the Russian Mikhail Bakunin, believed that capitalism and the state were inseparable, and that one could not be abolished without the other.

Paris Commune

In 1871, in the wake of the Franco-Prussian War, an uprising in Paris established the Paris Commune, which, according to Marx and Engels, for a few weeks provided a glimpse of a socialist society, before being brutally suppressed when the French government regained control.

From the outset the Commune was compelled to recognize that the working class, once come to power, could not manage with the old state machine; that in order not to lose again its only just conquered supremacy, this working class must, on the one hand, do away with all the old repressive machinery previously used against it itself, and, on the other, safeguard itself against its own deputies and officials, by declaring them all, without exception, subject to recall at any moment.

— Engels' 1891 postscript to The Civil War In France by Karl Marx[31]

In the Paris Commune large-scale industry was to be "based on the association of the workers" joined into "one great union", all posts in government were elected by universal franchise, elected officials took only the average worker's wage and were subject to recall. For Engels, this was what the dictatorship of the proletariat looked like (as opposed to the "dictatorship of the bourgeoisie", which was capitalism). Engels goes on to state: "In reality, however, the state is nothing but a machine for the oppression of one class by another, and indeed in the democratic republic no less than in the monarchy; and at best an evil inherited by the proletariat after its victorious struggle for class supremacy", and a new generation of socialists, "reared in new and free social conditions, will be able to throw the entire lumber of the state on the scrap-heap".[32]

After the Paris Commune, the differences between supporters of Marx and Engels and those of Bakunin were too great to bridge. The anarchist section of the First International was expelled from the International at the 1872 Hague Congress and they went on to form the Jura federation. The First International was disbanded in 1876.

The Second International

As the ideas of Marx and Engels took on flesh, particularly in central Europe, socialists sought to found a second "socialist" international, and in 1889, on the centennial of the French Revolution of 1789, the Second International was founded with 20 countries represented. Engels was elected honorary president at the third congress in 1893.

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of countries by system of government |

|

|

Just before his death in 1895, Engels argued that there was now a "single generally recognised, crystal clear theory of Marx" and a "single great international army of socialists". Despite its illegality due to the Anti-Socialist Laws of 1878 the Social Democratic Party of Germany's use of the limited universal male suffrage were "potent" new methods of struggle which demonstrated their growing strength and forced the dropping of the Anti-Socialist legislation, Engels argued.[33] By 1893, after the Anti-Socialist legislation was dropped in 1890, the German SPD obtained 1,787,000 votes, a quarter of votes cast. However the publication of Engels' views caused disquiet in the leadership of the SPD and they removed phrases they felt were too revolutionary.[34]

Marx believed that it was possible to have a peaceful socialist revolution in England, America and Holland, but not in France, where he believed there had been "perfected... an enormous bureaucratic and military organisation, with its ingenious state machinery" which must be forcibly overthrown. However, eight years after Marx's death, Engels argued that it was possible to achieve a peaceful socialist revolution in France, too.[35]

Germany

The SPD was by far the most powerful of the social democratic parties. Its votes reached 4.5 million, it had 90 daily newspapers, together with trade unions and co-ops, sports clubs, a youth organisation, a women's organisation and hundreds of full time officials. Under the pressure of this party, Bismarck introduced limited welfare provision and working hours were reduced. In addition, Germany experienced sustained economic growth for more than forty years. Commentators suggest that this expansion gave rise to illusions amongst the leadership of the SPD that capitalism would evolve into socialism gradually.

Beginning in 1896, in a series of articles published under the title "Problems of socialism", Eduard Bernstein argued that an evolutionary transition to socialism was both possible and more desirable than revolutionary change. Bernstein and his supporters came to be identified as "revisionists", because they sought to revise the classic tenets of Marxism. Although the orthodox Marxists in the party, led by Karl Kautsky, retained the Marxist theory of revolution as the official doctrine of the party, and it was repeatedly endorsed by SPD conferences, in practice the SPD leadership became increasingly reformist.

Russia

Bernstein coined the aphorism: "The movement is everything, the final goal nothing". But the path of reform appeared blocked to the Russian Marxists while Russia remained the bulwark of reaction. In the preface to the 1882 Russian edition to the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels had saluted the Russian Marxists who "formed the vanguard of revolutionary action in Europe." But the working class, although many were organised in vast modern western-owned enterprises, comprised no more than a small percentage of the population and "more than half the land is owned in common by the peasants". How was Russia to progress to socialism? Could Russia "pass directly" to socialism or "must it first pass through the same process" of capitalist development as the West? Marx and Engels replied: "If the Russian Revolution becomes the signal for a proletarian revolution in the West, so that both complement each other, the present Russian common ownership of land may serve as the starting point for a communist development."[36]

In 1903, the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party began to split on ideological and organizational questions into Bolshevik ('Majority') and Menshevik ('Minority') factions, with Lenin leading the more radical Bolsheviks. Both wings accepted that Russia was an economically backward country unripe for socialism. The Mensheviks awaited the capitalist revolution in Russia. But Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin argued that a revolution of the workers and peasants would achieve this task. After the Russian revolution of 1905, Leon Trotsky argued that unlike the French revolution of 1789 and the European Revolutions of 1848 against absolutism, the capitalist class would never organise a revolution in Russia to overthrow absolutism, and that this task fell to the working class who, liberating the peasantry from their feudal yoke, would then immediately pass on to the socialist tasks and seek a "permanent revolution" to achieve international socialism.[37]

Britain

After the Second International, in the first decades of the twentieth century, socialism became increasingly influential among many European intellectuals. In England, in 1884, middle class intellectuals organized the Fabian Society, a moderate form of socialism in opposition to Marxist ideas.

Amongst the British working class also, socialist ideas began to spread. In 1881 the Marxist Social Democratic Federation met, and in 1888 the successful Matchgirls Strike began a period of New Unionism in which members and former members of the Social Democratic Federation played a role. In 1889, Will Thorne, who was taught to read by Eleanor Marx, organized the Gasworkers, and gained a reduction in the working week from twelve hours a day to eight hours. In the same year, the London Dock Strike of 1889, organized by Tom Mann and Ben Tillett, (who like Thorne had been members of the Social Democratic Federation), won significant gains, and was seen as a landmark in British trade unionism.

The new unions brought a new socialist consciousness to the trade union movement. In 1899 the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants proposed that the Trade Union Congress call a special conference to bring together the trade unions and all the left-wing organisations to sponsor Parliamentary candidates independent of the Liberal Party. The Independent Labour Party, the Social Democratic Federation and the Fabians participated in the founding by the trade unions of the Labour Representation Committee in 1900, which became the Labour Party in 1906.

USA

In the U.S. the Socialist Labor Party of America was founded in 1877. This party, small as it was, became fragmented in the 1890s due to the infighting of various factions. In 1901 a merger between a moderate faction of the Socialist Labor Party of America and the younger Social Democratic Party joined with Eugene V. Debs to form the Socialist Party of America. The party grew to 150,000 in 1912 and polled 897,000 votes in the presidential campaign of that year, 6 percent of the total vote. It declined after the First World war.

France

After the failure of the Paris commune (1871), the French socialism was beheaded. Its leaders died or were exiled. In 1879, at the Marseille Congress workers' associations created the Federation of the Socialist Workers of France. Three years later, Jules Guesde and Paul Lafargue, the son-in-law of Karl Marx, left the federation and founded the French Workers' Party.

The Federation of the Socialist Workers of France was termed "possibilist" because it advocated gradual reforms, whereas the French Workers' Party promoted Marxism. In 1905 these two trends merged to form the French Section Française de l'Internationale Ouvrière (SFIO), led by Jean Jaurès and later Léon Blum. In 1906 it won 56 seats in Parliament. The SFIO adhered to Marxist ideas but became, in practice, a reformist party. By 1914 it had more than 100 members in the Chamber of Deputies.

The First World War

When the First World War began in 1914, many European socialist leaders supported their respective governments' war aims. The social democratic parties in the UK, France, Belgium and Germany supported their respective state's wartime military and economic planning, discarding their commitment to internationalism and solidarity.

Lenin, however, denounced the war as an imperialist conflict, and urged workers worldwide to use it as an occasion for proletarian revolution. The Second International dissolved during the war, while Lenin, Trotsky, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, together with a small number of other Marxists opposed to the war, came together in the Zimmerwald Conference in September 1915.

The Revolutions of 1917-23

After three long years, the First World War, at first greeted with enthusiastic patriotism, by 1917 had produced an upsurge of radicalism in most of Europe and also as far afield as the United States (see Socialism in the United States) and Australia.

In February 1917, revolution broke out in Russia and the workers, soldiers and peasants set up workers', soldiers' and peasants' councils (in Russian, soviets), although power still lay with the Provisional government. Lenin arrived in Russia in April 1917 and called for "All power to the Soviets". The Bolsheviks won a majority in the Soviets in October 1917 and at the same time the October Revolution was led by Lenin and Trotsky. At the Petrograd Soviet Lenin declared, "Long live the world socialist revolution!" [38]

In this period few Communists doubted, least of all Lenin and Trotsky, that the success of socialism in Soviet Russia depended on successful socialist revolutions carried out by the working classes of the most developed capitalist counties.[39][40] For this reason, in 1919, Lenin and Trotsky drew together the Communist Parties from around the world into a new 'International', the Communist International (also termed the Third International or Comintern).

The new Soviet government immediately nationalised the banks and major industry, and repudiated the former Romanov regime's national debts. It implemented a system of government through the elected workers' councils or soviets. It sued for peace and withdrew from the First World War. Arguably for the first time, socialism was not just a vision of a future society, but a description of an existing one, at least in embryo. But under siege from a trade boycott and invasion by Germany, UK, USA, France and other forces, facing civil war, and near starvation, the Soviet regime was forced to implement War Communism.

The Russian revolution of October 1917 gave rise to the formation of Communist Parties around the world, and the revolutions of 1917-23 which followed.

The German Revolution of 1918 overthrew the old absolutism and, like Russia, Workers' and Soldiers' Councils almost entirely made up of SPD and Independent Social Democrats (USPD) members were set up. The Weimar republic was established and placed the SPD in power, under the leadership of Friedrich Ebert. On the evening of 10 November 1918 a phone call took place between Ebert and General Wilhelm Groener, the new First General Quartermaster in Spa. The General assured Ebert of the support of the Army and therefore was given Ebert's promise to reinstate the military hierarchy and, with the help of the army, to take action against the Workers' Councils.[41] The Workers' and Soldiers' Councils were put down by the army and the Freikorps. In 1919 the Spartacist uprising challenged the power of the SPD government, but it was put down in blood and the German Communist leaders Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg were discovered and brutally murdered. A Communist regime under Kurt Eisner in Bavaria in 1919 was also put down in blood.

A Communist regime briefly held power under Béla Kun in Hungary. There were revolutionary movements in Vienna, the industrial centres of northern Italy, and revolutionary movements in the Ruhr area in Germany in 1920 and in Saxony in 1923. In the USA, the Communist Party USA was formed from former adherents of the Socialist Party of America. One of the founders, James Cannon, went on to become the leader of Trotskyist forces outside the Soviet Union.

In the UK, in 1918, the Labour Party adopted as its aim to secure for the workers, "the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange". In 1919, the Miners Federation, whose Members of Parliament pre-dated the formation of the Labour Party, and were since 1906 a part of that body, demanded the withdrawal of British troops from Russia. The 1919 Labour Party conference voted to discuss the question of affiliation to the Third (Communist) International, "to the distress of its leaders". [42] A vote was won committing the Labour Party committee of the Trades Union Congress to arrange "direct industrial action" to "stop capitalist attacks upon the Socialist Republics of Russia and Hungary." [43] The threat of immediate strike action forced the Conservative government to abandon its intervention in Russia.[44]

However, these revolutionary movements failed to spread the socialist revolution into the advanced capitalist countries of Europe. After Lenin's death in January 1924, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, falling steadily under the control of Stalin, turned to build "socialism in one country", namely the Soviet Union. Gradually, the Soviet Union developed a bureaucratic and authoritarian model of social development, which was condemned by moderate socialists, Trotskyists and others for undermining the initial socialist ideals of the Russian Revolution.[45]

The inter-war era and World War II

The Russian Revolution of 1917 brought about the definitive ideological division between Communists as denoted with a capital "C" on the one hand and other communist and socialist trends such as anarcho-communists and social democrats, on the other. The Left Opposition in the Soviet Union gave rise to Trotskyism which was to remain isolated and insignificant for another fifty years, except in Sri Lanka where Trotskyism gained the majority, and the pro-Moscow wing was expelled from the Communist Party.

In 1922 the fourth congress of the Communist International took up the policy of the United Front, urging Communists to work with rank and file Social Democrats while remaining critical of their leaders, who they criticised for "betraying" the working class by supporting the war efforts of their respective capitalist classes. For their part, the social democrats pointed to the dislocation caused by revolution, and later, the growing authoritarianism of the Communist Parties. When the Communist Party of Great Britain applied to affiliate to the Labour Party in 1920 it was turned down.

Britain

The inter-war years were a period of great hardship for the working class and one of of epic struggles. In 1919 the unions of the transport workers, the mine workers and the railway workers formed a Triple Alliance in the UK and held the possibility of taking power for the working class in their hands, in the assessment of the Prime Minister, Lloyd George. According to Robert Smillie, leader of the mine workers union, a founder member of the Independent Labour Party in 1889 and a Labour Party MP in the first 1924 Labour government, Lloyd George sent for him and the other leaders of the Triple Alliance in 1919 and told them:

Gentlemen, you have fashioned, in the Triple Alliance of the unions represented by you, a most powerful instrument. I feel bound to tell you that in our opinion we are at your mercy. The Army is disaffected and cannot be relied upon. Trouble has occurred already in a number of camps. We have just emerged from a great war and the people are eager for the reward of their sacrifices, and we are in no position to satisfy them. In these circumstances, if you carry out your threat and strike, then you will defeat us. But if you do so, have you weighed the consequences? The strike will be in defiance of the government of the country and by its very success will precipitate a constitutional crisis of the first importance. For, if a force arises in the state which is stronger than the state itself, then it must be ready to take on the functions of the state, or withdraw and accept the authority of the state. Gentlemen, have you considered, and if you have, are you ready?

— Aneurin Bevan, In Place of Fear [46]

"From that moment on", Smillie conceded to Aneurin Bevan, "we were beaten and we knew we were". When the UK General Strike of 1926 broke out, the trade union leaders, "had never worked out the revolutionary implications of direct action on such a scale", Bevan says. Bevan was a member of the Independent Labour Party and one of the leaders of the South Wales miners during the strike. The TUC called off the strike after nine days even as it was spreading. Workers' councils were being formed, with rank and file Communist Party members playing a role. The striking miners were locked out and remained locked out for six months. Bevan became a Labour MP in 1929.

In January 1924, the Labour Party formed a minority government for the first time with Ramsay MacDonald as prime minister. The Labour Party intended to ratify an Anglo-Russian trade agreement, which would break the trade embargo on Russia. This was attacked by the Conservatives and new elections took place in October 1924. Four days before polling day the Daily Mail published the Zinoviev letter, a forgery that claimed the Labour Party had links with Soviet Communists and was secretly fomenting revolution. The fears instilled by the press of a Labour Party in secret Communist manoeuvres, together with the half-hearted "respectable" policies persued by MacDonald, led to Labour losing the October 1924 general election. The victorious Conservatives repudiated the treaty.

The leadership of the Labour Party, like social democratic parties almost everywhere, (with the exception of Sweden and Belgium), tried to pursue a policy of moderation and economic orthodoxy. In the UK at times of depression this policy was not popular with the Labour Party’s working class supporters. The influence of Marxism grew in the UK Labour Party during the inter-war years. Anthony Crosland argued in 1956 that under the impact of the 1931 slump and the growth of fascism, the younger generation of left-wing intellectuals for the most part "took to Marxism", including the "best-known leaders" of the Fabian tradition, Sidney and Beatrice Webb. The Marxist Professor Harold Laski, who was to be chairman of the Labour Party in 1945-6, was the "outstanding influence" in the political field. [47]

The Marxists within the Labour Party differed in their attitude to the Communists. Some were expelled as "fellow travellers", while later others were Trotskyists working inside the Labour Party, especially in its youth wing where they were influential. The former mine worker Aneurin Bevan, who became an MP in 1929 and was to introduce the National Health Service into the UK in the Labour Government of 1945, considered himself a Marxist but was highly critical of the Soviet Union.

In 1929 the Labour Party won 288 seats out of 615. The depression of that period brought high unemployment and MacDonald sought to make cuts in order to balance the budget. The trade unions opposed MacDonald’s proposed cuts and he split the Labour government to form the National Government of 1931. This experience moved the Labour Party leftward, and at the start of the Second World War an official Labour Party pamphlet written by Harold Laski argued that, "the rise of Hitler and the methods by which he seeks to maintain and expand his power are deeply rooted in the economic and social system of Europe... economic nationalism, the fight for markets, the destruction of political democracy, the use of war as an instrument of national policy":

The war will leave its meed[48] of great problems, problems of internal social organisation... Business men and aristocrats, the old ruling classes of Europe, had their chance from 1919 to 1939; they failed to take advantage of it. They rebuilt the world in the image of their own vested interests... The ruling class has failed; this war is the proof of it. The time has come to give the common people the right to become the master of their own destiny... Capitalism has been tried; the results of its power are before us today. Imperialism has been tried; it is the foster-parent of this great agony. Given power [the Labour Party] will seek, as no other Party will seek, the basic transformation of our society. It will replace the profit-seeking motive by the motive of public service... there is now no prospect of domestic well-being or of international peace except in Socialism.

— Harold Laski, The Labour Party, the War and the Future (1939) [49]

USA

The Great Depression began in the United States on Black Tuesday, October 29, 1929. Unemployment rates passed 25%, prices and incomes fell 20–50%, but the debts remained at the same dollar amount. 9,000 banks failed during the decade of the 30s. By 1933, depositors saw $140 billion of their deposits disappear due to uninsured bank failures. [3]

The Minneapolis Teamsters Strike of 1934 led by the Trotskyist Communist League of America, the 1934 West Coast Longshore Strike led by the Communist Party USA, and the 1934 Toledo Auto-Lite Strike led by the American Workers Party, played an important role in the formation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in the USA, (becoming the AFL-CIO in 1955).

In Minnesota, in 1934, the General Drivers Local 574 of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters struck, despite an attempt to block the vote by AFL officials, demanding union recognition, increased wages, shorter hours, overtime rates, improved working conditions and job protection through seniority. In the battles that followed, which captured country-wide media attention, three strikes took place, martial law was declared and the National Guard was sent in. Two strikers were killed. Protest rallies of 40,000 were held. Farrell Dobbs, who became the leader of the local, had at the outset joined the "small and poverty-stricken" Communist League of America, founded by James P. Cannon and others in 1928 after their expulsion from the Communist Party USA for Trotskyism.[50]

The success of the CIO quickly followed its formation. In 1937, one of the founding unions of the CIO, the United Auto Workers, won union recognition at General Motors Corporation after a tumultuous forty-four day sit-down strike, while the Steel Workers Organizing Committee, which was formed by the CIO, won a collective bargaining agreement with U.S. Steel.

Germany

In 1928, the Communist International, now fully under the leadership of Stalin, turned from the united front policy to an ultra-left policy of the Third Period, a policy of aggressive confrontation of the social democracy. This divided the working class at a critical time.

Like the Labour Party in the UK, the Social Democratic Party in Germany, which was in power in 1928, followed an orthodox deflationary policy and pressed for reductions in unemployment benefits in order to save taxes and reduce budget deficits. These policies did not halt the recession and the government resigned.

The Communists described the Social Democratic leaders as "social fascists" and in the Prussian Landtag they voted with the Nazis to bring down the Social Democratic government. Fascism continued to grow, with powerful backing from industrialists, especially in heavy industry, and Hitler was invited into power in 1933.

Hitler's regime swiftly destroyed both the German Communist Party and the Social Democratic Party, the worst blow the world socialist movement had ever suffered. This forced Stalin to reassess his strategy, and from 1935 the Comintern began urging the formation of Popular Fronts, which were to include not just the Social Democratic parties but critically also "progressive capitalist" parties which were wedded to a capitalist policy.

After the election of a Popular Front government in Spain in 1936 a fascist military revolt led to the Spanish Civil War. The crisis in Spain also brought down the Popular Front government in France under Léon Blum. Ultimately the Popular Fronts were not able to prevent the spread of fascism or the aggressive plans of the fascist powers. Trotskyists considered Popular Fronts a "strike breaking conspiracy", an impediment to successful resistance to fascism due to their inclusion of pro-capitalist parties which demanded policies of opposition to strikes and workers’ actions against the capitalist class. [51]

Sweden

The Swedish Socialists formed a government in 1932. They broke with economic orthodoxy during the depression and carried out extensive public works financed from government borrowing. They emphasised large-scale intervention and the high unemployment they had inherited was eliminated by 1938. Their success encouraged the adoption of Keynesian policies of deficit financing pursued by almost all Western countries after World War Two.

Socialism after World War Two

In Western Europe, socialism gained perhaps its widest appeal in the period immediately following the end of World War II. Even where conservative governments remained in power, they were forced to adopt a series of social welfare reform measures, so that in most industrialized countries the postwar period saw the creation of a welfare state.

The period following the Second World War marked another period of intensifying struggle between socialists and communists. In the postwar period, the nominally socialist parties became increasingly identified with the expansion of the capitalist welfare state. Western European socialists largely backed U.S.-led Cold War policies. They largely supported the Marshall Plan and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, and denounced the Soviet Union as "totalitarian." Communists denounced these measures as imperialist provocations aimed at triggering a war against the Soviet Union. Inspired by the Second International, the Socialist International was organized in 1951 in Frankfurt, West Germany, without Communist participation.

In the postwar years, socialism became increasingly influential throughout the Third World. In 1949 the Chinese Revolution established a Communist state. Emerging nations of Africa, Asia, and Latin America frequently adopted socialist economic programs. In many instances, these nations nationalized industries held by foreign owners. The Soviet achievement in the 1930s seemed hugely impressive from the outside, and convinced many nationalists in the emerging former colonies of the Third World, not necessarily communists or even socialists, of the virtues of state planning and state-guided models of social development. This was later to have important consequences in countries like China, India and Egypt, which tried to import some aspects of the Soviet model.

In the 1970s, despite the radicalism of some socialist currents in the Third World, Western European Communist parties effectively abandoned their revolutionary goals and fully embraced electoral politics. Dubbed "Eurocommunism," this new orientation resembled earlier social-democratic configurations, although distinction between the two political tendencies persists.

In the late last quarter of the twentieth century, socialism in the Western world entered a new phase of crisis and uncertainty. Socialism came under heavy attack following the 1973 oil crisis. In this period, monetarists and neoliberals attacked social welfare systems as an impediment to individual entrepreneurship. With the rise of Ronald Reagan in the U.S. and Margaret Thatcher in Britain, the Western welfare state found itself under increasing political pressure. Increasingly, Western countries and international institutions rejected social democratic methods of Keynesian demand management, which were scrapped in favor of neoliberal policy prescriptions.

Western European socialists were under intense pressure to refashion their parties in the late 1980s and early 1990s and to reconcile their traditional economic programs with the integration of a European economic community based on liberalizing markets. The Labour Party in the United Kingdom put together a set of policies based on encouraging the market economy while promoting the involvement of private industry in delivering public services.

The last quarter of the twentieth century marked a period of major crisis for Communists in the Eastern bloc, where the growing shortages of housing and consumer goods, combined with the lack of individual rights to assembly and speech, began to disillusion more and more Communist party members. With the rapid collapse of Communist party rule in Eastern Europe between 1989 and 1991, the Soviet vision of socialism has effectively disappeared as a worldwide political force.

Contemporary socialism

In the 1960s and 1970s new social forces began to change the political landscape in the Western world. The long postwar boom, rising living standards for the industrial working class, and the rise of a mass university-educated white collar workforce began to break down the mass electoral base of European socialist parties. This new "post-industrial" white-collar workforce was less interested in traditional socialist policies such as state ownership and more interested in expanded personal freedom and liberal social policies.

Over the past twenty-five years, efforts to adapt socialism to new historical circumstances have led to a range of New Left ideas and theories, some of them contained within existing socialist movements and parties, others achieving mobilization and support in the arenas of "new social movements." Some socialist parties reacted more flexibly and successfully to these changes than others.

In the developing world, some elected noncommunist socialist parties and communist parties remain prominent, particularly in India. In China, the Chinese Communist Party has led a transition from the command economy of the Mao period, describing its economic program as market socialism or "socialism with Chinese characteristics." Under Deng Xiaoping, the leadership of China embarked upon a program of market-based reform that was more sweeping than had been Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev's perestroika program of the late 1980s. Deng's program, however, largely maintained state ownership rights over land, state or cooperative ownership of much of the heavy industrial and manufacturing sectors, and state influence in the banking and financial sectors. In Latin America, socialism has reemerged in recent years as a political banner in some areas. Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez and Bolivian President Evo Morales, for instance, refer to their political programs as socialist.

Socialism as an economic system

The term socialism is often used to refer to an economic system characterized by state ownership of the means of production and distribution. In the Soviet Union, state ownership of productive property was combined with central planning. Down to the workplace level, Soviet economic planners decided what goods and services were to be produced, how they were to be produced, in what quantities, and at what prices they were to be sold (see economy of the Soviet Union). Soviet economic planning was promoted as an alternative to allowing prices and production to be determined by the market through supply and demand. Especially during the Great Depression, many socialists considered Soviet-style planning a remedy to what they saw as the inherent flaws of capitalism, such as monopolies, business cycles, unemployment, vast inequalities in the distribution of wealth, and the exploitation of workers.

In the West, liberal economists such as Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman argued that socialist planned economies were doomed to failure. They asserted that central planners could never match the overall information inherent in the decision-making throughout a market economy (see economic calculation problem). Nor could enterprise managers in Soviet-style socialist economies match the motivation of private profit-driven entrepreneurs in a market economy.

Following the stagnation of the Soviet economy in the 1970s and 1980s, many socialists have begun to accept some of this critique. Polish economist Oskar Lange, for example, was an early proponent of "market socialism." He proposed a Central Planning Board that sets the prices of producer goods and controls the overall level of investment in the economy. The prices of producer goods would be determined through trial and error. The prices of consumer goods would be determined by supply and demand, with the supply coming from state-owned firms that would set their prices equal to the marginal cost, as in perfectly competitive markets. The Central Planning Board would distribute a "social dividend" to ensure reasonable income equality.[52]

In western Europe, particularly in the period after World War II, many socialist parties in government implemented what became known as mixed economies.[53] These govenments nationalised major and economically vital industries while permitting a free market to continue in the rest. These were most often monopolistic or infrastructural industries like mail, railways, power and other utilities. In some instances a number of small, competing and often relatively poorly financed companies in the same sector were nationalised to form one government monopoly for the purpose of competent management, of economic rescue (in the UK, British Leyland, Rolls Royce), or of competing on the world market[54]. Typically, this was achieved through compulsory purchase of the industry (i.e. with compensation). For example in the UK the nationalization of the coal mines in 1947 created a coal board charged with running the coal industry commercially so as to be able to meet the interest payable on the bonds which the former mine owners' shares had been converted into. [55][56]

These nationalised industries would frequently be combined with Keynsian economics and incomes policies to try and guide the whole economy.[57] Nevertheless, most economists, and many socialists, consider that these economies were (or are) capitalist economies, and the asperations of those who believed the mixed economy would abolish boom and slump, mass unemployment, and industrial unrest, were disappointed with the onset of the first world wide recession of 1973-4, the oil crisis of this period, and the monetary instability which followed. Some far left socialists, as well as some workers in the nationalised industries, also criticised the nationalisations for not estabilshing workers' control of the nationalised industries, through elected representatives, and the amount of compensation paid to the previous owners.

Some socialists propose various decentralized, worker-managed economic systems. One such system is the "cooperative economy," a largely free market economy in which workers manage the firms and democratically determine remuneration levels and labor divisions. Productive resources would be legally owned by the cooperative and rented to the workers, who would enjoy usufruct rights.[58] Another, more recent, variant is "participatory economics," wherein the economy is planned by decentralized councils of workers and consumers. Workers would be remunerated solely according to effort and sacrifice, so that those engaged in dangerous, uncomfortable, and strenuous work would receive the highest incomes and could thereby work less.[59]

Socialism and social and political theory

Marxist and non-Marxist social theorists have both generally agreed that socialism, as a doctrine, developed as a reaction to the rise of modern industrial capitalism, but differ sharply on the exact nature of the relationship. Émile Durkheim saw socialism as rooted in the desire simply to bring the state closer to the realm of individual activity as a response to the growing anomie of capitalist society. Max Weber saw in socialism an acceleration of the process of rationalization commenced under capitalism. Weber was a critic of socialism who warned that putting the economy under the total bureaucratic control of the state would not result in liberation but an 'iron cage of future bondage.'

Socialist intellectuals continued to retain considerable influence on European philosophy in the mid-20th century. Herbert Marcuse's 1955 Eros and Civilization was an explicit attempt to merge Marxism with Freudianism. Structuralism, widely influential in mid-20th century French academic circles, emerged as a model of the social sciences that influenced the 1960s and 1970s socialist New Left.

Criticisms of socialism

Criticisms of socialism range from disagreements over the efficiency of socialist economic and political models to condemnation of states described by themselves or others as "socialist." Many economic liberals, such as Friedrich Hayek in his book The Road to Serfdom,[60] argue that the social control over distribution of wealth and private property advocated by socialists cannot be achieved without reduced prosperity for the general populace and a loss of political and economic freedoms.[61] There is much focus on the economic performance and human rights records of Communist states, although some proponents of socialism reject the categorization of such states as socialist.

Notes

- ^ "Socialism" Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ Commenting on the death of milliner Mary Anne Walkley, 20 years old, who died after working uninterruptedly for 26 1/2 hours, the respectable Morning Star, 23 June 1863, said, 'Our white slaves, who are toiled into the grave, for the most part silently pine and die.' Quoted in Marx, Karl, Capital, p365, Pelican, 1976 [1]

- ^ Crosland, Anthony, The Future of Socialism, (1956)

- ^ Bevan, Aneurin, In Place of Fear, (1951).

- ^ "Market socialism," Dictionary of the Social Sciences. Craig Calhoun, ed. Oxford University Press 2002; and "Market socialism" The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics. Ed. Iain McLean and Alistair McMillan. Oxford University Press, 2003. See also Joseph Stiglitz, "Whither Socialism?" Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995 for a recent analysis of the market socialism model of mid-20th century economists Oskar R. Lange, Abba P. Lerner, and Fred M. Taylor.

- ^ Socialist International. "Declaration of principles" (HTML). Socialist International. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, entry on Socialism

- ^ The Cambridge History of Iran Volume 3, The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Period, edited by Ehsan Yarshater, Parts 1 and 2, p1019, Cambridge University Press (1983)

- ^ Morris, William, Dream of John Ball: A King's Lesson Project Gutenberg, accessed 11 July, 2007

- ^ Rousseau, Jean-Jacques, Social Contract, p2, Penguin, (1968)

- ^ Leroux called socialism “the doctrine which would not give up any of the principles of Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” of the French Revolution of 1789. "Individualism and socialism" (1834)

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, etymology of socialism

- ^ Williams, Raymond (1976). Keywords: a vocabulary of culture and society. Fontana. 0006334792.

- ^ Engels, Frederick, Preface to the 1888 English Edition of the Communist Manifesto, p202. Penguin (2002)

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica, Saint Simon; Socialism

- ^ New Lanark World Heritage Site accessed 8 July, 2007

- ^ http://www.learningcurve.gov.uk/snapshots/snapshot13/snapshot13.htm The National Archives (UK government records and information management) The 1833 Factory Act: did it solve the problems of children in factories?] accessed 7 July, 2007

- ^ From the Foundation Axioms of Owen's "Society for Promoting National Regeneration", 1833

- ^ Owen, Robert, Paper Dedicated to the Governments of Great Britain, Austria, Russia, France, Prussia and the United States of America London 1841

- ^ Kropotkin, P.A., 1910, Anarchism, in the Encyclopedia Britannica 11th-13th editions.

- ^ Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph, 1851, General Idea of the Revolution in the 19th Century, studies 6 & 7.

- ^ Revolutionary Catechism, Mikhail Bakunin, 1866

- ^ [2]

- ^ Engels' 1891 postscript to The Civil War In France by Karl Marx,Marx, Engels, Selected works in one volume, p257, Lawrence and Wishart (1968)

- ^ Marx, Karl, Critique of the Gotha Programme, p320-1, Selected Works, Lawrence and Wishart, (1968)

- ^ Engels, Frederick, Anti-Dühring, 1877

- ^ The Soviet Union did not claim to have reached a communist society, even though it was ruled by a Communist party for more than seven decades. For Communists, the name of the party is not meant to reflect the name of the social system but rather the party's ultimate goal.

- ^ Marx and Engels, The Communist Manifesto, Penguin Classics (2002), p224

- ^ In the English language, this slogan eventually became, "Workers of the world unite".

- ^ MIA: Encyclopedia of Marxism: Glossary of Organisations, First International (International Workingmen’s Association), accessed 5 July, 2007

- ^ Marx, Engels, Selected works in one volume, p257, Lawrence and Wishart (1968)

- ^ Engels' 1891 Preface to Marx, Civil War in France, Selected Works in one volume, Lawrence and Wishart, (1968), p256, p259

- ^ Engels, 1895 Introduction to Marx's Class Struggles in France 1848-1850

- ^ cf Footnote 449 in Marx Engels Collected Works on Engels' 1895 Introduction to Marx's Class Struggles in France 1848-1850

- ^ Fischer, Ernst, Marx in his own words, p135, quoting from Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte

- ^ Marx, Engels, Preface to the Russian Edition of 1882, Communist Manifesto, p196, Penguin Classics, 2002

- ^ Trotsky, Leon, The Permanent Revolution and Results and Prospects, p169ff. New Park, (1962)

- ^ Lenin, Meeting of the Petrograd Soviet of workers and soldiers' deputies October 25, 1917, Collected works, Vol 26, p239. Lawrence and Wishart, (1964)

- ^ Bertil, Hessel, Introduction, Theses, Resolutions and Manifestos of the first four congresses of the Third International, pxiii, Ink Links (1980)

- ^ "We have always proclaimed and repeated this elementary truth of marxism, that the victory of socialism requires the joint efforts of workers in a number of advanced countries." Lenin, Sochineniya (Works), 5th ed Vol XLIV p418, February 1922. (Quoted by Mosche Lewin in Lenin's Last Struggle, p4. Pluto (1975))

- ^ According to notes taken by Max von Baden, Ebert had declared on 7 November, 1918: "If the Kaiser doesn't abdicate the social revolution is unavoidable. But I don't want it, indeed I hate it like sin." Zitiert nach v. Baden: Erinnerungen und Dokumente S. 599 f.

- ^ Cole and Postgate, The Common People, p551

- ^ Sylvia Pankhurst, 'The British Workers and Soviet Russia', published in The Revolutionary Age, August 9, 1919

- ^ Sylvia Pankhurst reported that, "The London district committee of the dockers has decided to declare a strike on July 20 and 21, but it goes further, it had decided to advise its members to abstain from working on any ships bound for Russia or assisting in any way the overthrow of the Russian proletariat". Sylvia Pankhurst, 'The British Workers and Soviet Russia', published in The Revolutionary Age, August 9, 1919.

- ^

Brinton, Maurice (1975). "The Bolsheviks and Workers' Control 1917-1921 : The State and Counter-revolution" (HTML). Solidarity. Retrieved 22nd January.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Bevan, Aneurin, In Place of Fear p40. MacGibbon and Kee, (1961). Bevan reports verbatim what Robert Smillie told him of his meeting with Lloyd George.

- ^ Crosland, Anthony, The Future of Socialism, p4 and note 2

- ^ Meed - literally, 'Reward', here used sardonically

- ^ Published by the Labour Party in November 1939

- ^ Dobbs, Farrell, Teamster Rebellion, Monad Press, New York, (1972), p21ff, p34, p92

- ^ [http://marxists.catbull.com/archive/trotsky/1936/whitherfrance/ch03a.htm Trotsky, Leon, France at a Turning Point, (1936) in Wither France, p105. New Park, 1974

- ^ John Barkley Rosser and Marina V. Rosser, Comparative Economics in a Transforming World Economy (Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press, 2004).

- ^ For instance, in the biography of the the 1945 Labour Party Prime Minister Clem Attlee, Beckett states "the government... wanted what would become known as a mixed economy". Beckett, Francis, Clem Attlee, (2007) Politico's. Beckett also makes the point that "Everyone called the 1945 government 'socialist'."

- ^ In the UK, British Aerospace was a combination of major aircraft companies British Aircraft Corporation, Hawker Siddeley and others. British Shipbuilders was a combination of the major shipbuilding companies including Cammell Laird, Govan Shipbuilders, Swan Hunter, and Yarrow Shipbuilders

- ^ Socialist Party of Great Britain (1985). The Strike Weapon: Lessons of the Miners’ Strike (PDF). London. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hardcastle, Edgar (1947). "The Nationalisation of the Railways". Socialist Standard. 43 (1). Socialist Party of Great Britain. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^ Mattick, Paul. "Marx and Keynes : the limits of the mixed economy" (HTML). Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^ For more information on the cooperative economy, see Jaroslav Vanek, The Participatory Economy (Ithaca, NY.: Cornell University Press, 1971).

- ^ For more information on participatory economics, see Michael Albert and Robin Hahnel, The Political Economy of Participatory Economics (Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press, 1991).

- ^ Hayek, Friedrich (1994). The Road to Serfdom (50th anniversary ed. ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-32061-8.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Hans-Hermann Hoppe. A Theory of Socialism and Capitalism. Kluwer Academic Publishers. page 46 in PDF.

References and further reading

- Guy Ankerl, Beyond Monopoly Capitaism and Monopoly Socialism, Cambridge MA: Schenkman, 1978.-

- G.D.H. Cole, History of Socialist Thought, in 7 volumes, Macmillan and St. Martin's Press, 1965; Palgrave Macmillan, 2003 reprint; 7 volumes, hardcover, 3160 pages, ISBN 1-4039-0264-X.

- Friedrich Engels, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, Zurich, 1884. LCC HQ504 .E6.

- Albert Fried and Ronald Sanders, eds., Socialist Thought: A Documentary History, Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor, 1964. LCCN 64-0 – 0.

- Phil Gasper, The Communist Manifesto: A Road Map to History's Most Important Political Document, Haymarket Books, paperback, 224 pages, 2005. ISBN 1-931859-25-6.

- Élie Halévy, Histoire du Socialisme Européen. Paris, Gallimard, 1948.

- Michael Harrington, Socialism, New York: Bantam, 1972. LCCN 76-0.

- Jesús Huerta de Soto, Socialismo, cálculo económico y función empresarial (Socialism, Economic Calculation, and Entrepreneurship), Unión Editorial, 1992. ISBN 84-7209-420-0.

- Makoto Itoh, Political Economy of Socialism. London: Macmillan, 1995. ISBN 0333553373.

- Oskar Lange, On the Economic Theory of Socialism, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1938. LCCN 38-0 – 0.

- Michael Lebowitz, Build It Now: Socialism for the 21st Century, Monthly Review Press, 2006. ISBN 1-58367-145-5.

- Ludwig von Mises, Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis, Liberty Fund, 1922. ISBN 0-913966-63-0.

- Joshua Muravchik, Heaven on Earth: The Rise and Fall of Socialism, San Francisco: Encounter Books, 2002. ISBN 1-893554-45-7.

- Michael Newman, Socialism: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-19-280431-6.

- Bertell Ollman, ed., Market Socialism: The Debate among Socialists, Routledge, 1998. ISBN 0-415-91967-3.

- Leo Panitch, Renewing Socialism: Democracy, Strategy, and Imagination. ISBN 0-8133-9821-5.

- Richard Pipes, Property and Freedom, Vintage, 2000. ISBN 0-375-70447-7.

- John Barkley Rosser and Marina V. Rosser, Comparative Economics in a Transforming World Economy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004. ISBN 9780262182348.

- David Selbourne, Against Socialist Illusion, London, 1985. ISBN 0-333-37095-3.

- James Weinstein, Long Detour: The History and Future of the American Left, Westview Press, 2003, hardcover, 272 pages. ISBN 0-8133-4104-3.

- Peter Wilberg, Deep Socialism: A New Manifesto of Marxist Ethics and Economics, 2003. ISBN 1-904519-02-4.

- Edmund Wilson, To the Finland Station: A Study in the Writing and Acting of History, Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1940. LCCN 4-0 – 00.

See also

- Alter-globalization

- Anti-capitalism

- Fabian Society

- History of socialism in Great Britain

- Labour movement

- Participatory economics

- Progressivism

- Socialism in the United States

- Syndicalism

- An equal amount of products for an equal amount of labor

External links

- Resources on socialism

- The Marxists Internet Archive (online library of Marxist writers)

- Marxist.net - a resource on socialist writers

- History of socialism at Spartacus Educational

- Modern History Sourcebook on socialism

- Socialist history at What Next?

- PBS' "Heaven on Earth: the Rise and Fall of Socialism"

- Towards a New Socialism by W. Paul Cockshott and Allin Cottrell

- Katherine Verdery: Anthropology of Socialist Societies

- Introductory articles

- "Why Socialism?" by Albert Einstein

- "Socialism: Utopian and Scientific" by Friedrich Engels

- "The Soul of Man under Socialism" by Oscar Wilde

- "Socialism and Liberty" by George Bernard Shaw

- "The Two Souls of Socialsm" by Hal Draper

- "Approaching Socialism" by Harry Magdoff and Fred Magdoff

- Socialist organizations

- Committee for a Workers' International

- Industrial Workers of the World

- World Socialist Web Site published by the International Committee of the Fourth International

- The Party for Socialism and Liberation

- The Party of European Socialists

- The Socialist International

- Socialist Party (England & Wales)

- Socialist Party USA

- Socialist Workers Party

- Critical appraisals

- "Socialism", by Robert Heilbroner

- "Socialism" Economic Policy 2nd Lecture, by Ludwig von Mises

- "The Intellectuals and Socialism", by Friedrich A. Hayek

- "A Theory of Socialism and Capitalism", by Hans-Hermann Hoppe

- Lecture XXXV "A Philosophy of Life" includes a critique of marxist socialism by Sigmund Freud

- "State socialism and anarchism" by Benjamin Tucker

- "Towards a New Socialism?" Review Essay by Len Brewster