Rastafari

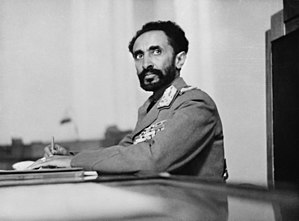

The Rastafari movement (also known as Rastafari, Rastafarianism or simply Rasta) is a monotheistic, Abrahamic, new religious movement[1] that accepts Haile Selassie I, the former Emperor of Ethiopia, as God incarnate, called Jah[2] or Jah Rastafari. He is also seen as part of the Holy Trinity and as the returned messiah promised in the Bible.

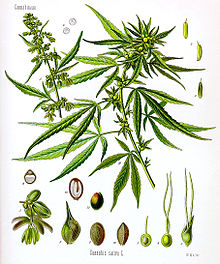

Other characteristics of Rastafari include the spiritual use of cannabis, [3][4] and various Afrocentric social and political aspirations,[3][5] such as the teachings of Jamaican publicist, organiser, and black separatist Marcus Garvey (also often regarded as a prophet), whose political and cultural vision helped inspire a new world view.

The name Rastafari comes from Ras (literally "Head," an Ethiopian title equivalent to Duke), and Tafari Makonnen, the pre-coronation name of Haile Selassie I. Rastafari is commonly called "Rastafarianism," by some academics, but this term is considered derogatory and offensive by Rastas themselves[6].

Doctrines

Rastafari developed among poor Jamaicans of African descent who felt they were oppressed and that society was apathetic to their problems.[3][7] Rastas may regard themselves as conforming to certain visions of how Africans should live,[3][8] reclaiming what they see as a culture stolen from them when their ancestors were brought on slave ships to Jamaica, the movement's birthplace. The messages expounded by the Rastafari promote love and respect for all living things and emphasize the paramount importance of human dignity and self-respect. Above all else, they speak of freedom from spiritual, psychological as well as physical slavery and oppression. In their attempts to heal the wounds inflicted upon African people by colonialism, Rastafari extol the virtue and superiority of African cultures past and present.

Rastafari stress loyalty to their vision of Zion, and rejection of modern society, calling it Babylon, which they see as corrupt.[3][9][5] "Babylon" in this case is considered to have been in rebellion against "Earth's Rightful Ruler" (JAH) ever since the days of the biblical king Nimrod. The movement is difficult to categorize, because Rastafari is not a centralized organization.[3][10] Individual Rastafari work out their religion for themselves, resulting in a wide variety of doctrines.

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

Afrocentrism

Socially, Rastafari has been viewed as a response to racist oppression of black people as it was experienced both in the world as a whole (where Selassie was the only black monarch recognised in international circles) and in Jamaica. In 1930s Jamaica, black people were at the bottom of the social order, while white people were at the top. Marcus Garvey's encouragement of black people to take pride in themselves and their African heritage inspired the Rastas to embrace all things African. They taught that they were brainwashed while in captivity to negate all things black and African. They turned the white image of them—as primitive and straight out of the jungle—into a defiant embrace of the African culture they saw as having been stolen from them when they were taken from Africa on the slave ships. In Rastafarian teachings, Africa is associated with Zion, and Africa/Zion is the starting place of all human ancestry as well as the original state of mind that can be reached through meditation and the ganja herb.

Living close to and as a part of nature is seen as African. This African approach to "naturality" is seen in the dreadlocks, ganja, ital food, and all aspects of Rasta life. They disdain conventional ways of life as unnatural and excessively objective, and also those who reject subjectivity. Rastas say that scientists try to discover how the world is by looking from the outside in, whereas the Rasta approach is to see life from the inside, looking out. The individual is given tremendous importance in Rastafari, and every Rasta has to figure out the truth for himself.

Another important Rastafarian identification is with the colours red, gold, and green, of the Ethiopian flag as well as (with the addition of black) the colours of "Pan-African Unity" for Marcus Garvey. They are a symbol of the Rastafari movement, and of the loyalty Rastas feel toward Haile Selassie, Ethiopia, and Africa. These colours are frequently seen on clothing and other decorations. Red stands for the blood shed during slavery, green stands for the vegetation of Africa, while gold stands for the prosperity Africa had to offer before most of the gold and diamonds were extracted during slavery. It also represents the sun, which gives everything life.

Some Rastafari learn Amharic, which some consider to be the original language, because this was the language of Haile Selassie I and in order to further their identity as Ethiopian. There are reggae songs written in Amharic. Most Rastas speak either a form of English or forms of their native languages that embrace non-standard dialects and have been modified to accord with and display an individual Rasta's world view (e.g. "I-and-I" rather than "I" or "me", acknowledging the presence in the person of both the individual and the divine.).

Haile Selassie and the Bible

One belief that unites many Rastafari is that Ras[11] Tafari Makonnen, who was crowned Haile Selassie I, Emperor of Ethiopia on November 2, 1930, is the living God incarnate, called Jah, who is the black Messiah who will lead all those of righteous livity into a promised land of full emancipation and divine justice called Zion (new Earth Isaiah 65:17) This is partly because of his titles King of Kings, Elect of God and Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah. These titles are a close match for those of the Messiah mentioned in Revelation 5:5 (which verse reads "Lord of Lords" rather than "Elect of God".) However, according to Ethiopian tradition, these Imperial titles were accorded to all Solomonic emperors beginning in 980 BC—well before Revelation was written in the first century AD. Haile Selassie was, according to some traditions, the 225th in an unbroken line of Ethiopian monarchs descended from the Biblical King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Psalm 87:4-6 is also interpreted as predicting the coronation of Haile Selassie I.

In the 10th century BC, The Solomonic Dynasty of Ethiopia was founded by Menelik I, the son of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, who had visited Solomon in Israel. 1 Kings 10:13 claims "And King Solomon gave unto the Queen of Sheba all her desire, whatsoever she asked, beside that which Solomon gave her of his royal bounty. So she turned and went to her own country, she and her servants." On the basis of the Ethiopian national epic, the Kebra Negast, Rastas interpret this verse as meaning she conceived his child, and from this, conclude that African people are among the true children of Israel, or Jews. Beta Israel black Jews have lived in Ethiopia for centuries, disconnected from the rest of Judaism; their existence gave some credence and impetus to early Rastafari, validating their belief that Ethiopia was Zion.

Some Rastafari choose to classify their movement as Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity, Protestant Christianity, or Judaism. Of those, the ties to the Ethiopian Church are the most widespread, although this is controversial to many Ethiopian clergy. Rastafari believe that standard translations of the Bible incorporate changes created by the white power structure. Some also revere the Kebra Negast, but many of these Rastas would classify themselves as Ethiopian Orthodox in religion and Rastafari in ideology. Some Rastafari pay little attention to the Kebra Negast, and most consider it as having nowhere near the sanctity of the Bible.

For Rastafari, Selassie I remains their god and their king.[12] They see Selassie as being worthy of worship, and as having stood with great dignity in front of the world's press and in front of representatives of many of the world's powerful nations, especially during his appeal to the League of Nations in 1936, when he was still the only independent black monarch in Africa.[12] From the beginning the Rastas decided that their personal loyalty lay with Africa's only black monarch, Selassie, and that they themselves were in effect as free citizens of Ethiopia, loyal to its Emperor and devoted to its flag.

Most Rastafari believe that Selassie is in some way a reincarnation of Jesus and that the Rastafari are the true Israelites. At the heart of Rastafari is the belief in being one's own 'kingman' or prince (hence they call themselves Rastafari). As Ras Midas sang "When I saw my Daddy with the pick axe and my Mommy with the broom, then I know Rastaman is in exile" (Ras Midas, Rastaman in Exile, 1980). Rastas say they have been conditioned into slavery, but convert this into a belief in their own divine potential, believing that as Selassie I dwells within them, they also are worthy kings and princes.

Rastas call Selassie Jah, or Jah Rastafari, and believe there is great power in all these names. They call themselves Rastafari (Template:PronEng) to express the personal relationship each Rasta has with Selassie I. Rastas like to use the ordinal with the name Haile Selassie I, with the dynastic Roman numeral one signifying "the First" deliberately pronounced as the letter I - again as a means of expressing a personal relationship with God. They also call Selassie H.I.M. (pronounced him), for His Imperial Majesty.

Of great importance is that Rastafari[3] do not accept that God could die and thus believe that Selassie's 1975 supposed death was a hoax, and that he will return to liberate his followers. A few Rastas today consider this a partial fulfillment of prophecy found in the apocalyptic 2 Esdras 7:28. Rastafari is a strongly syncretic Abrahamic religion that draws extensively from the Bible. Adherents look particularly to the New Testament Book of Revelation, as this (5:5) is where they find the prophecies about the divinity of Haile Selassie. Rastas believe that they, and the rest of the black race, are descendants of the ancient twelve tribes of Israel, cast into captivity outside Africa as a result of the slave trade.

Some believe that only half of the Bible has been written, and that the other half, stolen from them along with their culture, is written in a man's heart. This concept also embraced the idea that even the illiterate can be Rastas by reading God's Word in their hearts. Rastas also see the lost half of the Bible, and the whole of their lost culture to be found in the Ark of the Covenant, a repository of African wisdom.

Rastafari are criticised, particularly by Christian groups, for taking Biblical quotes out of context, for picking and choosing what they want from the Bible, and for bringing elements into Rastafari that do not appear in the Bible. They are also criticised for using an English language translation (particularly the King James Version) of the Bible, as many have no interest in Hebrew or Greek scholarship. However, a great interest in the Amharic Orthodox version, authorized by Haile Selassie I in the 1950s, has arisen among Rastas. Selassie himself wrote in the preface to this version that "unless [one] accepts with clear conscience the Bible and its great Message, he cannot hope for salvation," thus confirming and coinciding with what the Rastafari themselves had been preaching since the beginning of the movement.[13]

Controversy

There is controversy about some statements made by Haile Selassie when asked directly about the Rastas' claims regarding him. During a 1966 visit to Jamaica, although he refused many requests to deny divinity, he replied to such a question by Edward Allen, Minister of Education, by stating that he was indeed fully human. This was taken by members of the media as a denial of divinity; however several Rastafari theologians have pointed out that according to the miaphysite doctrines held by the Emperor's Ethiopian Orthodox Church, Jesus Christ is indeed fully human, in addition to being fully divine in one indivisible nature; and that His Majesty replied subtly and wisely by pointing out one of the attributes of Christ that he possessed — much as Jesus is said to have responded subtly to Pilate and others who questioned him in this way according to the Gospels. According to this argument, if Selassie's admitting to being fully human would disqualify him from also being divine, then it must also exclude Christ on precisely the same grounds. They take a similar view with regard to his Majesty's response to Bill McNeil of the CBC in 1968 aboard a train in Canada, which they claim is likewise ambiguous and subtle.

Church and the Holy Trinity

Generally, Rastas assert that their own body is the true church or temple of God, and so see no need to make temples or churches out of physical buildings.

Rasta doctrines concerning the Holy Trinity are mostly related to the name Haile Selassie meaning Power of the Trinity in Ge'ez, but the exact significance of this tends to vary. Many Rastas claim that Haile Selassie I represents God the Father and God the Son/Yahoshua/Jesus and the Holy Trinity, while all human beings potentially embody the Holy Spirit. Some Rastas see Melchizedek, in addition to Jesus, as having been former incarnations of Haile Selassie.

Repatriation and race

The Rastas say that Haile Selassie will call the Day of Judgment, when the righteous shall return home to Mount Zion, identified with Africa, to live forever in peace, love, and harmony. In the meantime the Rastas call to be repatriated to Africa. Repatriation, the desire to return to Africa after 400 years of slavery, is central to Rastafari doctrine. The first Rastas, living on a Caribbean island, dreamed of the possibilities of Africa with the encouragement of Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association and the Black Star Line Shipping company. Haile Selassie had given Black people of the West 500 gashas of land in Shashemene, Ethiopia, for repatriation, in appreciation for services rendered by Black Americans and Jamaicans in the Ethiopian-Italian War of 1934 to 1941.[citation needed]

Many early Rastas for a time believed in black supremacy. Widespread advocacy of this doctrine was shortlived, at least partly because of Selassie's explicit condemnation of racism in a speech before the United Nations. Most Rastas now espouse a belief that racial animosities must be set aside, with world peace and harmony being common themes. One of the three major modern houses of Rastafari, the Twelve Tribes of Israel, has specifically condemned all types of racism, and declared that the teachings of the Bible are the route to spiritual liberation for people of any racial or ethnic background. Haile Selassie said "We must become members of a new race void of petty predjudices", and "Until the philosophy which holds one race superior and another inferior is finally and permanently discredited and abandoned...[WAR]", and "I hope to see a time when we no longer speak in terms of Black or White."[citation needed]

Some early elements of Rastafari were closely related to indigenous religions of the Caribbean and Africa, and to the Maroons, though the more syncretic elements were largely purged by the Nyahbinghi warriors– dreadlocked Rastas who opposed some leaders who sought to add them to the Rastafari doctrines.[citation needed]

People of all races are to be found within the movement.

Physical immortality/Paradise

Many Rastas are physical immortalists who believe the chosen few will continue to live forever in their current bodies. This is commonly called "Everliving" life, particularly in the context of "Life Everliving with Jah" as king and Amharic the official language. This replaces the term "everlasting", as "last" in "everlasting" implies an end (as in the term "at last"), while the life the Rastas have will never end according to them.

A good expression of this doctrine is in Lincoln Thompson's song Thanksgiving. After asking "What's destroying life?" he says, "Tell I if you know." Paraphrasing the Bible, he continues, "There are too many dead bodies lying around me...in a true reality, down in the grave there is no life. In silence there you'll be, with no-one to hear nor see, and no matter what you saw, when you are dead you cannot praise Jah." Another may be seen in the lyrics to the Third World's anthem, "96 Degrees in the Shade":

- As sure as the Sun shine

- Way up in the sky,

- Today I stand here a victim -

- The truth is I'll never die...

Perhaps the most well known example of this is Bob Marley's refusal to write a will despite suffering from the final stages of an advanced metastasized cancer (and the resulting controversy surrounding the distribution of his estate after his death) on the grounds that writing a will would mean he was giving in to death and forgoing his chance at everliving life.

For Rastafarians, Zion (paradise) is to be found in Africa, and more specifically in Ethiopia, where the term is also in use. Some Rastas believe themselves to represent the real Children of Israel in modern times, and their goal is to repatriate to Africa, or to Zion. Rasta reggae is peppered with references to Zion; among the best-known examples are the Bob Marley songs '"Zion Train," "Iron Lion Zion," the Damian Marley song "Road to Zion," and Lauryn Hill "Zion". Reggae groups such as Steel Pulse and Cocoa Tea also have many references to Zion in their various songs. In recent years, such references have also "crossed over" into pop music thanks to artists like Sublime, Slightly Stoopid, Lauryn Hill, Boney M (Rivers of Babylon), Dreadzone with the reggae-tinged track "Zion Youth."

Diet

Many Rastas eat limited types of meat in accordance with the dietary Laws of the Old Testament; they do not eat shellfish or pork. Others abstain from all meat and flesh whatsoever, asserting that to touch meat is to touch death, and is therefore a violation of the Nazirite oath. (A few make a special exception allowing fish, while abstaining from all other forms of flesh.) However, the prohibition against meat only applies to those who are currently fulfilling a Nazirite vow ("Dreadlocks Priesthood"), for the duration of the vow. Many Rastafari maintain a vegan or vegetarian diet all of the time. The purpose of fasting (abstaining from meat and dairy) is to cleanse the body in accordance to serving in the presence of the "Ark of the Covenent".

Usage of alcohol is also generally deemed unhealthy to the Rastafarian way of life, partly because it is seen as a tool of Babylon to confuse people, and partly because placing something that is pickled and fermented within oneself is felt to be much like turning the body (the Temple) into a "cemetery".

In consequence, a rich "alternative" cuisine has developed in association with Rastafari tenets, eschewing most synthetic additives, and preferring more natural vegetables and fruits such as coconut and mango. This cuisine can be found throughout the Caribbean and in some restaurants throughout the western world.

Some of the Houses (or "Mansions" as they have come to be known) of the Rastafari culture, such as the Twelve Tribes of Israel do not specify diet beyond that which to quote Christ "Is not what goes into a man's mouth that defile him, but what come out of it". Wine is seen as a "mocker" and strong drink is "raging", however simple consumption of beer or the very common "Roots Wine" are not systematically a part of Rastafarian culture this way or that. Separating from Jamaican culture, different interpretations on the role of food and drink within what some might call a religion remains up for debate. At official state banquets Haile Selassie would encourage guests to "eat and drink in your own way".

Politics

Rastafari culture does not encourage mainstream political involvement. In fact, in the early stages of the movement most Rastas did not vote, out of principle. Ras Sam Brown formed the Suffering People's Party for the Jamaican elections of 1962. Although he received fewer than 100 votes, simply standing for election was seen as a powerful act. In the election campaign of 1972, People's National Party leader Michael Manley used a prop, a walking stick given to him by Haile Selassie, which was called the "Rod of Correction", in a direct appeal to Rastafarian values.

In the famous free One Love Peace Concert on April 22, 1978, Peter Tosh lambasted the audience, including attending dignitaries, with political demands that included decriminalising cannabis. He did this while smoking a spliff, a criminal act in Jamaica. Five months after this event, Tosh was badly beaten by the Jamaican authorities. At this same concert, Bob Marley led both then-Prime Minister Michael Manley and opposition leader Edward Seaga onto the stage; and a famous picture was taken with all three of them holding their hands together above their heads in a symbolic gesture of peace during what had been a very violent election campaign.

Language

Rastas believe that their original African languages were stolen from them when they were taken into captivity as part of the slave trade, and that English is an imposed colonial language. Their remedy for this situation has been the creation of a modified vocabulary and dialect, reflecting their desire to take forward language and to confront the society they call Babylon.

Rastas have also changed some common words to reflect their beliefs. Some examples are:

- "I-tal" is derived from the word vital and is used to describe the diet of the movement which is taken mainly from Hebrew dietary laws.

- "Overstanding" replaces "understanding" to denote an enlightenment which places one in a better position.

- "Irie" (pronounced eye-ree) is a term used to denote acceptance, positive feelings, or to describe something that is good.

- "Upfulness" is a positive term for being helpful

- "Livication" is substituted for the word "dedication" because Rastas associate ded-ication with death.

- "Downpression" is used in place of "oppression," the logic being that the pressure is being applied from a position of power to put down the victim.

- "Zion" is used to describe the Paradise of Jah or Ethiopia.

- One of the most distinctive modifications in "Iyaric" is the substitution of the pronoun "I-and-I" for other pronouns, usually the first person. "I", as used in the examples above, refers to Jah; therefore, "I-and-I" in the first person includes the presence of the divine within the individual. As "I-and-I" can also refer to "us," "them," or even "you," it is used as a practical linguistic rejection of the separation of the individual from the larger Rastafari community, and Jah himself.

"-isms"

Rastafari say that they reject "-isms". They see a wide range of "isms and schisms" in modern society and want no part in them, for example communism and capitalism. They especially reject the word Rastafarianism, because they see themselves as having transcended "isms and schisms". This has created some conflict between Rastas and some members of the academic community studying the Rastafari phenomenon, who insist on calling this religious belief Rastafarianism, in spite of the disapproval this generates within the Rastafari movement. Nevertheless, the practice continues among scholars. However, the study of Rasta using its own terms has occurred[14].

Ceremonies

There are two types of Rasta religious ceremonies. A reasoning is a simple event where the Rastas gather, smoke marijuana ("ganja"), and discuss ethical, social, and religious issues. The person honored by being allowed to light the herb says a short prayer beforehand, and the ganja is passed in a clockwise fashion except in time of war when it is passed counterclockwise. A binghi or grounation is a holy day; the name binghi is derived from Nyabinghi, believed to be an ancient, and now extinct, order of militant blacks in eastern Africa that vowed to end oppression. Binghis are marked by much dancing, singing, feasting, and the smoking of ganja, and can last for several days.

Some important dates when grounations may take place are:

- January 7 - Orthodox (Ethiopian) Christmas

- february 7 Ethiopian new year

- April 21 - The anniversary of Emperor Haile Selassie I's visit to Jamaica. Also known as Grounation Day.

- July 23 - The birthday of Emperor Haile Selassie I

- August 17 - The birthday of Marcus Garvey

- November 2 - The coronation of Emperor Haile Selassie I

Symbols

Dreadlocks

The wearing of dreadlocks is very closely associated with the movement, though not universal among, or exclusive to, its adherents. Rastas believe dreadlocks to be supported by Leviticus 21:5 ("They shall not make baldness upon their head, neither shall they shave off the corner of their beard, nor make any cuttings in the flesh.") and the Nazirite vow in Numbers 6:5 ("All the days of the vow of his separation there shall no razor come upon his head: until the days be fulfilled, in the which he separateth himself unto the LORD, he shall be holy, and shall let the locks of the hair of his head grow.").

It has often been suggested (eg. Campbell 1985) that the first Rasta dreadlocks were copied from Kenya in 1953, when images of the independence struggle of the feared maumau insurgents, who grew their "dreaded locks" while hiding in the mountains, appeared in newsreels and other publications that reached Jamaica. However, a more recent study by Barry Chevannes[15] has traced the first dreadlocked Rastas to a subgroup first appearing in 1949, known as Youth Black Faith.

There have been ascetic groups within a variety of world faiths that have at times worn similarly matted hair. In addition to the Nazirites of Judaism and the Sadhus of Hinduism, it is worn among some sects of Sufi Islam, notably the Baye Fall sect of Mourides,[16] and by some Ethiopian Orthodox monks in Christianity,[17] among others. Some of the very earliest Christians may also have worn this hairstyle; particularly noteworthy are descriptions of James the Just, "brother of Jesus" and first Bishop of Jerusalem, whom Hegesippus (according to Eusebius and Jerome) described as a Nazirite who never once cut his hair. The length of a Rasta's dreads is a measure of wisdom, maturity, and knowledge in that it can indicate not only the Rasta's age, but also his/her time as a Rasta.

Also, according to the Bible, Samson was a Nazarite who had "seven locks". Rastas argue that these "seven locks" could only have been dreadlocks,[18] as it is unlikely to refer to seven strands of hair.

Dreadlocks have also come to symbolize the Lion of Judah (its mane) and rebellion against Babylon. In the United States, several public schools and workplaces have lost lawsuits as the result of banning dreadlocks. Safeway is an early example, and the victory of eight children in a suit against their Lafayette, Louisiana school was a landmark decision in favor of Rastafari rights.

Rastafari associate dreadlocks with a spiritual journey that one takes in the process of locking their hair (growing dreadlocks). It is taught that patience is the key to growing dreadlocks, a journey of the mind, soul and spirituality. Its spiritual pattern is aligned with the Rastafari movement. The way to form natural dreadlocks is to allow hair to grow in its natural pattern, without cutting, combing or brushing, but simply to wash it with pure water.

For the Rastas the razor, the scissors and the comb are the three Babylonian or Roman inventions.[19] So close is the association between dreadlocks and Rastafari, that the two are sometimes used synonymously. In reggae music, a follower of Rastafari may be referred to simply as a dreadlocks or Natty (natural) Dread, whilst those non-believers who cut their hair are referred to as baldheads.

As important and connected with the movement as the wearing of dreadlocks is, though, it is not deemed necessary for, or equivalent to, true faith. Popular slogans, often incorporated within Reggae lyrics, include: "Not every dread is a Rasta and not every Rasta is a dread..."; "It's not the dread upon your head, but the love inna your heart, that mek ya Rastaman" (Sugar Minott); and as Morgan Heritage sings: "You don't haffi dread to be Rasta...," and "Children of Selassie I, don't lose your faith; whether you do or don't have your locks 'pon your head..."

Many non-Rastafari of black African descent have also adopted dreads as an expression of pride in their ethnic identity, or simply as a hairstyle, and take a less purist approach to developing and grooming them, adding various substances such as beeswax in an attempt to assist the locking process. The wearing of dreads also has spread among people of other ethnicities, including those whose hair is not naturally suited to the style, and who sometimes go to great lengths to form them. Dreads worn for stylish reasons are sometimes referred to as "bathroom locks," to distinguish them from the kind that are purely natural. Rasta purists also sometimes refer to such dreadlocked individuals as "wolves," as in "a wolf in sheep's clothing," especially when they are seen as trouble-makers who might potentially discredit or infiltrate Rastafari.[20]

Ganja

For Rastas, smoking cannabis, usually known as healing of the nation, ganja, or herb, and never as a "weed"[citation needed], is a spiritual act, often accompanied by Bible study; they consider it a sacrament that cleans the body and mind, heals the soul, exalts the consciousness, facilitates peacefulness, brings pleasure, and brings them closer to Jah. The burning of the herb is often said to be essential "for it will sting in the hearts of those that promote and perform evil and wrongs." By the 8th century, cannabis had been introduced by Arab traders to Central and Southern Africa, where it is known as dagga,[21] and many Rastas say it is a part of their African culture that they are reclaiming.[22] It is sometimes also referred to as "the healing of the nation", a phraseology adapted from Revelation 22:2.[23] While there is a clear belief in the beneficial qualities of cannabis, it is not compulsory to use it, and there are Rastas who do not.

According to many Rastas, the illegality of cannabis in many nations is evidence that persecution of Rastafari is a reality. They are not surprised that it is illegal, seeing it as a powerful substance that opens people's minds to the truth — something the Babylon system, they reason, clearly does not want.[24] They contrast their herb to alcohol and other drugs, which they feel destroy the mind.[25].

They believe that the smoking of cannabis enjoys Biblical sanction and is an aid to meditation and religious observance.

Among Biblical verses Rastas believe justify the use of cannabis:

- Genesis 1:11 "And God said, Let the earth bring forth grass, the herb yielding seed, and the fruit tree yielding fruit after his kind, whose seed is in itself, upon the earth: and it was so."

- Genesis 3:18 "... thou shalt eat the herb of the field."

- Proverbs 15:17 "Better is a dinner of herbs where love is, than a stalled ox and hatred therewith."[2]

- Psalms 104:14 "He causeth the grass to grow for the cattle, and herb for the service of man."

According to some Rastafarian[26] and other scholars, the etymology of the word "cannabis" and similar terms in all the languages of the Near East may be traced to the Hebrew qaneh bosm קנה-בשם, which is one of the herbs God commanded Moses to include in his preparation of sacred anointing perfume in Exodus 30:23; the Hebrew term also appears in Isaiah 43:24; Jeremiah 6:20; Ezekiel 27:19; and Song of Songs 4:14. Deuterocanonical and canonical references to the patriarchs Adam, Noah, Abraham and Moses "burning incense before the Lord" are also applied, and many Rastas today refer to cannabis by the term ishence — a slightly changed form of the English word "incense". It is also said that cannabis was the first plant to grow on King Solomon's grave.

The migration of many thousands of Hindus from India to the Caribbean in the 20th century may have brought this culture to Jamaica. Many academics point to Indo-Caribbean origins for the ganja sacrament resulting from the importation of Indian migrant workers in a post-abolition Jamaican landscape. “Large scale use of ganja in Jamaica…dated from the importation of indentured Indians…”(Campbell 110). Dreadlocked mystics, often ascetic, known as the Sadhus, have smoked cannabis in India for centuries.[27]

In 1998, then-Attorney General of the United States Janet Reno, though not a judge, opined that Rastafari do not have the religious right to smoke ganja in violation of the United States' drug laws. The position is the same in the United Kingdom, where, in the Court of Appeal case of R. v. Taylor [2002] 1 Cr. App. R. 37, it was held that the UK's prohibition on cannabis use did not contravene the right to freedom of religion conferred under the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms.

In July 2008, however, the Italian Supreme Court ruled that Rastafarians must be allowed to possess greater amounts of cannabis legally, owing to its use by them as a sacrament.[28][29]

History of the Rastafari movement

Ethiopian world view

Before Garvey, there had been two major circumstances that proved conducive to the conditions that established a fertile ground for the incubation of Rastafari in Jamaica: the history of resistance, exemplified by the Maroons, and the forming of an Afrocentric, Ethiopian world view with the spread of such religious movements as Bedwardism, which flourished from the 1890s to the 1920s. These groups had long carried a tradition of what musician Bob Marley referred to as 'resisting against the system.'

Marcus Garvey

Rastas see Marcus Mosiah Garvey as a prophet, with his philosophy fundamentally shaping the movement, and with many of the early Rastas having started out as Garveyites. He is often seen as a second John the Baptist. One of the most famous prophecies attributed to him involving the coronation of Haile Selassie I was the 1927 pronouncement "Look to Africa, for there a king shall be crowned," although an associate of Garvey's, James Morris Webb, had made very similar public statements as early as 1921.[30][31] Marcus Garvey promoted Black Nationalism, black separatism, and Pan-Africanism: the belief that all black people of the world should join in brotherhood and work to decolonise the continent of Africa — then still controlled by the white colonialist powers.

He promoted his cause of black pride throughout the 1920s and 1930s, and was particularly successful and influential among lower-class blacks in Jamaica and in rural communities. Although his ideas have been hugely influential in the development of Rastafari culture, Garvey never identified himself with the movement, and even wrote an article critical of Haile Selassie for leaving Ethiopia at the time of the Fascist occupation.[32] In addition, his Universal Negro Improvement Association disagreed with Leonard Howell over Howell's teaching that Haile Selassie was the Messiah.[32] Rastafari nonetheless may be seen as an extension of Garveyism. In early Rasta folklore, it is the Black Star Liner (actually a shipping company bought by Garvey to encourage repatriation to Liberia) that takes them home to Africa.

Early written foundations

Although not strictly speaking a 'Rastafarian' document, The Holy Piby written by Robert Athlyi Rogers from Anguilla in the 1920s, is acclaimed by many Rastafarians as a formative and primary source. Robert Athlyi Rogers founded an Afrocentric religion known as "Athlicanism" in the US and West Indies in the 1920s. Rogers' religious movement, the Afro-Athlican Constructive Church, saw Ethiopians (in the Biblical sense of all Black Africans) as the chosen people of God, and proclaimed Marcus Garvey, the prominent Black Nationalist, an apostle. The church preached self-reliance and self-determination for Africans.

The Royal Parchment Scroll of Black Supremacy, written during the 1920s by a preacher called Fitz Balintine Pettersburg, is a surrealistic stream-of-consciousness polemic against the white colonial power structure that is also considered formative, a palimpsest of Afrocentric thought, brimming with rage and energy.

The first document to appear that can be labelled as truly Rastafari was Leonard P. Howell's The Promise Key, written using the pen name G.G. [for Gangun-Guru] Maragh, in the early 1930s. In it, he claims to have witnessed the Coronation of the Emperor and Empress on 2 November 1930 in Addis Ababa, and proclaims the doctrine that H.I.M. Ras Tafari is the true Head of Creation and that the King of England is an imposter. This tract was written while Howell was jailed on charges of sedition.

Emergence

Emperor Haile Selassie I, whom some of the Rastafarians call Jah, was crowned "King of Kings, Elect of God, and Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah" in Addis Ababa on November 2, 1930. The event created great publicity throughout the world, including in Jamaica, and particularly through two consecutive Time magazine articles about the coronation (he was later named Time's Person of the Year for 1935, the first Black person to appear on the cover), as well as two consecutive National Geographic issues around the same time. Haile Selassie almost immediately gained a following as both God and King amongst poor Jamaicans, who came to be known as Rastafarians, and who looked to their Bibles, and saw what they believed to be the fulfilling of many prophecies from the book of Revelation. As Ethiopia was the only African country to be free from colonialism, and Haile Selassie was the only black leader accepted among the kings and queens of Europe, the early Rastas viewed him with great reverence.

Over the next two years, three Jamaicans who all happened to be overseas at the time of the coronation, each returned home and independently began, as street preachers, to proclaim the divinity of the newly-crowned Emperor as the returned Christ[33], arising from their interpretations of Biblical prophecy and based partly on Haile Selassie's status as the only African monarch of a fully independent state, with the titles King of Kings and Conquering Lion of Judah (Revelation 5:5).

First, on 8 December 1930, Archibald Dunkley, formerly a seaman, landed at Port Antonio and soon began his ministry; in 1933, he relocated to Kingston where the King of Kings Ethiopian Mission was founded. Joseph Hibbert returned from Costa Rica in 1931 and started spreading his own conviction of the Emperor's divinity in Benoah district, Saint Andrew Parish, through his own ministry, called Ethiopian Coptic Faith; he too moved to Kingston the next year, to find Leonard Howell already teaching many of these same doctrines, having returned to Jamaica around the same time. With the addition of Robert Hinds, himself a Garveyite and former Bedwardite, these four preachers soon began to attract a following among Jamaica's poorer classes, who were already beginning to look to Ethiopia for morale support.

Leonard Howell

Leonard Howell, who has been described as the "first Rasta",[34] became the first to be persecuted, charged with sedition for refusing loyalty to the King of England George V. The British government would not tolerate Jamaicans loyal to Haile Selassie in what was then regarded as their colony. When he was released, he formed a commune which grew as large as 2,000 people[35] at a place called Pinnacle, at St. Catherine in Jamaica.

Visit of Selassie I to Jamaica

Haile Selassie I had already met with several Rasta elders in Addis Ababa in 1961, giving them gold medals, and had allowed West Indians of African descent to settle on his personal land in Shashamane in the 1950s. The first actual Rastafarian settler, Papa Noel Dyer, arrived in September 1965, having hitch-hiked all the way from England.

Haile Selassie visited Jamaica on April 21, 1966. Somewhere between one and two hundred thousand Rastafari from all over Jamaica descended on Kingston airport having heard that the man whom they considered to be God was coming to visit them. They waited at the airport smoking a great amount of cannabis and playing drums. When Haile Selassie arrived at the airport he delayed disembarking from the aeroplane for an hour until Mortimer Planno, a well-known Rasta, personally welcomed him. From then on, the visit was a success. Rita Marley, Bob Marley's wife, converted to the Rastafari faith after seeing Haile Selassie; she has stated that she saw stigmata appear on his person, and was instantly convinced of his divinity.

The great significance of this event in the development of the Rastafari movement should not be underestimated. Having been outcasts in society, they gained a temporary respectability for the first time. By making Rasta more acceptable, it opened the way for the commercialisation of reggae, leading in turn to the further global spread of Rastafari.

Because of Haile Selassie's visit, April 21 is celebrated as Grounation Day. It was during this visit that Selassie I famously told the Rastafari community leaders that they should not emigrate to Ethiopia until they had first liberated the people of Jamaica. This dictum came to be known as "liberation before repatriation."

Walter Rodney

In 1968, Walter Rodney, a Guyanese national, author, and professor at the University of the West Indies, published a pamphlet titled The Groundings with My Brothers which among other matters, including a summary of African history, discussed his experiences with the Rastafarians. It became a benchmark in the Caribbean Black Power movement. Combined with Rastafarian teachings, both philosophies spread rapidly to various Caribbean nations, including Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, Dominica, and Grenada.

Music

| ||

| Music of Jamaica | ||

| General topics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Related articles | ||

| Genres | ||

|

|

||

| Nationalistic and patriotic songs | ||

|

||

| Regional music | ||

|

||

Music has long played an integral role in Rastafari, and the connection between the movement and various kinds of music has become well known, due to the international fame of reggae musicians like Bob Marley and Peter Tosh.

Niyabinghi chants are played at worship ceremonies called grounations, that include drumming, chanting and dancing, along with prayer and ritual smoking of cannabis. The name Nyabinghi comes from an East African movement from the 1850s to the 1950s that was led by people who militarily opposed European imperialism. This form of nyabinghi was centered around Muhumusa, a healing woman from Uganda who organized resistance against German colonialists. The British in Africa later led efforts against Nyabinghi, classifying it as witchcraft through the Witchcraft Ordinance of 1912.[citation needed] In Jamaica, the concepts of Nyabinghi were appropriated for similar anti-colonial efforts, and it is often danced to invoke the power of Jah against an oppressor.

The drum is a symbol of the Africanness of Rastafari, and some mansions assert that Jah's spirit of divine energy is present in the drum. African music survived slavery because many slaveowners encouraged it as a method of keeping morale high. Afro-Caribbean music arose with the influx of influences from the native peoples of Jamaica, as well as the European slaveowners.

Another style of Rastafarian music is called burru drumming, first played in the Parish of Clarendon, Jamaica, and then in West Kingston. Burru was later introduced to the burgeoning Rasta community in Kingston by a Jamaican musician named Count Ossie. He mentored many influential Jamaican ska, rock steady, and reggae musicians. Through his tutelage, they began combining New Orleans R&B, folk mento, jonkanoo, kumina, and revival zion into a unique sound. The burru style, which centers on three drums - the bass, the alto fundeh, and the repeater - would later be copied by hip hop DJs.[36]

Maroons, or communities of escaped slaves, kept purer African musical traditions alive in the interior of Jamaica, and were also contributing founders of Rastafari.

Reggae

Reggae was born amidst poor blacks in Trenchtown, the main ghetto of Kingston, Jamaica, who listened to radio stations from the United States. Jamaican musicians, many of them Rastas, soon blended traditional Jamaican folk music and drumming with American R&B, and jazz into ska, that later developed into reggae under the influence of soul.

Reggae began to enter international consciousness in the early 1970s, and Rastafari mushroomed in popularity internationally, largely due to the fame of Bob Marley, who actively and devoutly preached Rastafari, incorporating nyabinghi and Rastafarian chanting into his music, lyrics and album covers. Songs like "Rastaman Chant" led to the movement and reggae music being seen as closely intertwined in the consciousness of audiences across the world (especially among oppressed and poor groups of African Americans and Native Americans, First Nations Canadians, Australian Aborigines and New Zealand Māori, and throughout most of Africa). Other famous reggae musicians with strong Rastafarian elements in their music include Peter Tosh, Freddie McGregor, Toots and The Maytals, Burning Spear, Black Uhuru, Ras Michael,Jah Cure, Turbulence, Prince Lincoln Thompson, Bunny Wailer, Prince Far I, Israel Vibration, The Congos, Mikey Dread and literally hundreds more.

Reggae music expressing Rasta doctrine

The first reggae single that sang about Rastafari and reached Number 1 in the Jamaican charts was Bongo Man by Little Roy in 1969.[37] Early Rasta reggae musicians (besides Marley) whose music expresses Rastafari doctrine well are Peter Tosh, Bunny Wailer (in Blackheart Man), Prince Far I, Linval Thompson, Ijahman Levi (especially the first 4 albums), Misty-in-Roots (Live), The Congos (Heart of the Congos), The Rastafarians, The Abyssinians, Culture, Big Youth, and Ras Michael And The Sons Of Negus. The Jamaican jazz percussionist Count Ossie, who had played on a number of ska and reggae recordings, recorded albums with themes relating to Rasta history, doctrine, and culture.

Rastafari doctrine as developed in the '80s was further expressed musically by a number of other prominent artists, such as Burning Spear, Steel Pulse, Third World, The Gladiators, Black Uhuru, Aswad, and Israel Vibration. Rastafari ideas have spread beyond the Jamaican community to other countries including Russia, where artists such as Jah Division write songs about Jah. Afro-American hardcore punk band Bad Brains are notable followers of the Rastafari movement and have written songs ("I Against I", etc.) that promote the doctrine.

In the 21st century, Rastafari sentiments are spread through roots reggae and dancehall, subgroups of reggae music, with many of their most important proponents promoting the Rastafari religion, such as Capleton, Sizzla, Anthony B, Barrington Levy, Turbulence, Jah Mason, Pressure, Midnite, Natural Black, Daweh Congo, Luciano, Cocoa Tea, or Richie Spice. Several of these acts have gained mainstream success and frequently appear on the popular music charts. Most recently artists such as Damian Marley (son of Bob Marley) have blended hip-hop with reggae to re-energize classic Rastafari issues such as social injustice, revolution and the honour and responsibility of parenthood using contemporary musical style.

Berlin-based dub techno label "Basic Channel" has subsidiary labels called "Rhythm & Sound" and "Burial Mix" whose lyrics strongly focus on many aspects of Rastafari culture and ideology, including the acceptance of Haile Selassie I. Notable tracks include "Jah Rule", "Mash Down Babylon", "We Be Troddin'", and "See Mi Yah".

Jamaican reggae artist Jah Cure also praises Jah and the Rastafari movement in many of his songs, as do two Sinéad O'Connor rastafari/reggae CDs– "Throw Down Your Arms" and "Theology".

There are several Jamaican films that are paramount to the history of Rastafari, such as Rockers, The Harder They Come, Land of Look Behind and Countryman.

Rastafari today

Today, the Rastafari movement has spread throughout much of the world, largely through interest generated by reggae music—most notably, that of Jamaican singer/songwriter Bob Marley. By 1997, there were around one million Rastafari faithful worldwide.[38] About five to ten percent of Jamaicans identify themselves as Rastafari.[citation needed]

By claiming Haile Selassie I as the returned messiah, Rastafari may be seen as a new religious movement that has arisen from Judaism and Christianity. Rastafari is not a highly organized religion; it is a movement and an ideology. Many Rastas say that it is not a "religion" at all, but a "Way of Life".[39] Most Rastas do not claim any sect or denomination, and thus encourage one another to find faith and inspiration within themselves, although some do identify strongly with one of the "mansions of Rastafari" — the three most prominent of these being the Nyahbinghi, the Bobo Ashanti and the Twelve Tribes of Israel. In 1996, the International Rastafari Development Society was given consultative status by the United Nations.[40]

By the end of the twentieth century, women played a greater role in the expression of the Rastafari movement. In the early years, and in a few of the stricter "mansions" (denominations), menstruating women were subordinated and excluded from religious and social ceremonies. To a large degree, women feel more freedom to express themselves now, thus they contribute greatly to the movement.

Today, Rastas are not just Black African, but also include other diverse ethnic groups including Native American, White, Māori, Indonesian, Thai, etc. Additionally, in the 1990s, the word Rastaman became part of the vocabulary of the Post-Soviet states. After the fall of the USSR, a youth subculture of cannabis users formed, primarily in Russia and Ukraine, many of whom began to call themselves Rastamany ("растаманы", in plural).[41] They adopted a number of symbols of Rastafari culture, including Reggae music (especially honouring Bob Marley), the green-gold-red colours, and sometimes dreadlocks,[42] but not Afrocentrism (most are ethnically Slavic). Many of them protest against what they call "Babylon". A Russian Reggae scene has developed that is only partially similar to common reggae. Rastamany have their own folklore, publish literature and records, as well as create websites and form online communities.

St Agnes Place contained a Rastafari place of worship in London until it was evicted in 2006.[43]

A small but devoted Rasta community developed in Japan in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Rasta shops selling natural foods, Reggae recordings, and other Rasta-related items sprang up in Tokyo, Osaka, and other cities. For several years, "Japan Splashes" or open-air Reggae concerts were held in various locations throughout Japan. For a review by two sociologists of how the Japanese Rasta movement can be explained in the context of modern Japanese society, see Dean W. Collinwood and Osamu Kusatsu, "Japanese Rastafarians: Non-Conformity in Modern Japan," The Study of International Relations, No. 26, Tokyo: Tsuda College, March 2000 (research conducted in 1986 and 1987). Many Rastafarian Marketplaces and small shops have sprung up in Kensington Market in Toronto. Canada has a large amount of Rastafarians mainly consisting of Black people and persons of Native Canadian heritage.

See also

- Awake Zion

- Bedwardism

- Ethiopian suit

- List of topics related to Black and African people

- Mansions of Rastafari

- Bob Marley

- Rastafarian vocabulary

- Reggae

- Spiritual use of cannabis

- Vegetarianism and religion

References

- ^ "Dread Jesus": A New View of the Rastafari Movement

- ^ the Rasta name for God incarnate, from a shortened form of Jehovah found in Psalms 68:4 in the King James Version of the Bible

- ^ a b c d e f g Dread, The Rastafarians of Jamaica, by Joseph Owens ISBN 0-435-98650-3

- ^ The Ganja Complex: Rastafari and Marijuana by Ansley Hamid (2002)

- ^ a b Chanting Down Babylon p. 342-343.

- ^ Encyclopedia of African and African-American Religions p. 263 by Stephen D. Glazier, 2001

- ^ Edmonds, p. 3.

- ^ Edmonds, p. 57.

- ^ Edmonds, p. 54

- ^ Edmonds, p. 121.

- ^ Amharic title of nobility corresponding to Prince or Duke; also having the meaning "Head".

- ^ a b The Rastafarians by Leonard E. Barrett, p. 252.

- ^ Words of Ras Tafari

- ^ Professor Rex Nettleford, Ceremonial Address on Behalf of University of West Indies to "Marley's Music: Reggae, Rastafari, and Jamaican Culture" conference, in Bob Marley: The Man and His Music (2003)

- ^ Barry Chevannes, 1998 Rastafari and Other African-Caribbean Worldviews, chap. 4

- ^ Islamic Society and State Power in Senegal, p. 167 by Leonardo Alfonso Villalón 1995

- ^ Neil J. Savinsky in Chanting Down Babylon p. 133, 143 fn.#37; citing David Buxton, The Abyssinians, p. 78.

- ^ The Kebra Negest: The Lost Bible of Rastafarian Wisdom and Faith, p. 49

- ^ cf. Chanting Down Babylon p. 32; The Kebra Nagast: The Lost Bible of Rastafarian Wisdom and Faith by Gerlad Hausman p. 48; Rastafarianismby Gerhardus Cornelis Oosthuizen p. 16; An Educator's Classroom Guide to America's Religious Beliefs and Practices p. 155.

- ^ Chanting Down Babylon, p. 2

- ^ Hamid, The Ganja Complex: Rastafari and Marijuana, introduction, p. xxxii.

- ^ Chanting Down Babylon, p. 130 ff.

- ^ Rastafari and Other African-Caribbean Worldviews by Barry Chevannes, p. 35, 85; Edmonds, p. 52

- ^ Edmonds, p. 61

- ^ Chanting Down Babylon, p. 354.

- ^ Marijuana and the Bible, published by the Ethiopian Zion Coptic Church

- ^ Arrow of the Blue-Skinned God: Retracing the Ramayana Through India, Jonah Blank, p. 89.

- ^ Reuters - Rasta pot smokers win legal leeway in Italy

- ^ AOL News - Rasta smoker wins appeal of marijuana conviction

- ^ http://rastaites.com/repatriationnews/09repatriation.htm

- ^ IRIE Barbados Groundation Report

- ^ a b http://www.jamaicans.com/culture/rasta/keyfigures.htm

- ^ The Rastafarians by Leonard E. Barrett, pp. 81-82

- ^ The First Rasta: Leonard Howell and the Rise of Rastafarianism by Helene Lee, 1999

- ^ Rastafari: From Outcasts to Culture Bearers by Ennis Barrington Edmonds, p. 37.

- ^ Jeff Chang Can't Stop, Won't Stop. 2005: St. Martin's Press. Pages 24-25.

- ^ Mark Lamaar, Radio 2

- ^ Chanting Down Babylon p. 1

- ^ [1]

- ^ UN Report of the Committee on Non-Governmental Organizations

- ^ Russian Reggae Rasta Roots — a 1997 report on Russian Rasta by Shohdy Naguib

- ^ The eXile Field Guide to Moscow: Russian Rasta — a satiric account about Russian Rastaman by The eXile

- ^ BBC NEWS | UK | Anger amid Rastafarian temple raid

- Dread, The Rastafarians of Jamaica, by Joseph Owens ISBN 0-435-98650-3

- Experience, by Lincoln Thompson

- Soul Rebels: The Rastafari, by William F Lewis

- Rastafari: A Way of Life, by Tracy Nicholas ISBN 0-948-39016-6

- Book of Memory: A Rastafari Testimony, composed by Prince Elijah Williams and edited by Michael Kuelker ISBN 0-9746021-0-8

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. |

- Rastafarianism Scholarly profile] at the Religious Movements Homepage (University of Virginia)

- Ethiopia Africa Black International Congress

- Black Culture

- Rastafari

- A Sketch of Rastafari History

- A New Faculty of Interpretation

- introductory video and scholarly paper

- Well-written and simple site explaining basic Rasta ideas.

- Old academic article

- Jamaican Observer article about Rasta and politics

- Marcus Garvey's prophecy of Haile Selassie I

- Garvey critical of Haile Selassie I

- Rastafari use of cannabis

- Guam court case over Rasta cannabis possession as sacrament

- Jamaican Gleaner 2001 letter asking not to call the religion Rastafarianism

- Essay in PDF format on Rasta and Christafari

- History, Background and facts: Leonard Barrett The Rastafarians

- Ba Beta Kristyan Haile Selassie I - Church of Haile Selasse I

- Articles documenting history of Rastafari in Jamaica

- Rastafari Today, an Online Magazine

- (fr) Trailer of a documentary about the first Rastas