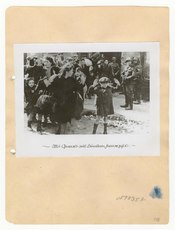

Photo of the boy from the Warsaw Ghetto

The photo of the boy from the Warsaw Ghetto is a black-and-white image that is one of the most famous photographic depictions of the Holocaust . It was probably created in April or May 1943 during the uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto and is part of the so-called Stroop Report , in which Jürgen Stroop documented the suppression of the uprising he had ordered. The photo, which in the Stroop report is titled “Forcibly taken out of bunkers”, shows arrested Jewsbeing driven out of a building by German troops. Among them is a little boy who developed into the central element of the reception of photography and who gave the photo his name. Like most of the other people depicted and the photographer, his identity could not be established beyond doubt. Only one of the German soldiers has been identified with any certainty.

The photo shows a remarkable history of reception. Already mentioned in the Nuremberg trial of major war criminals , it developed into one of the most frequently processed photographic representations of the National Socialist crimes against European Jews from the 1960s onwards . In addition to its use in history books and documentation material, it has been taken up in the visual arts, literature and films. Historians and cultural scientists also devoted themselves to photography to a greater extent. Several monographs were published that deal with the history of the creation and reception of the photo. Since 2017, the Stroop report and the photos it contains have been part of the UNESCO World Document Heritage .

The Warsaw Ghetto and the Uprising

On September 1, 1939, the Second World War began with the attack on Poland , in which the National Socialist German Reich attacked the Second Polish Republic in violation of international law . Shortly afterwards there was the battle for Warsaw , which ended in late September with the occupation of the city by German troops. About a year later, Hans Frank , Governor General of the Occupied Territories, announced in a decree the formation of a ghetto in the old Jewish quarter of Warsaw, in which the city's approximately 360,000 Jewish residents would be crammed together. In mid-November 1940, this area was separated from the rest of the city by walls and barbed wire. From December 1st, all Jews in Warsaw who were 12 years or older were required to wear a white armband with a blue Star of David on their right arm. From the beginning of 1941 Jews from other Polish regions and the German Reich as well as a few hundred Roma were brought to the Warsaw ghetto, so that it temporarily reached a population of 445,000. Several thousand of them died each month from starvation, typhus and indiscriminate shootings. From July 22, 1942 , the German occupiers deported the majority of the ghetto residents to the Treblinka extermination camp northeast of Warsaw as part of the so-called Great Action , in order to murder them there. According to National Socialist statistics, over 300,000 people died in this way by the beginning of October.

Over time, various resistance groups had formed in the ghetto. The main groups were the Jewish Fighting Organization consisting of representatives of the Jewish youth organizations Hashomer Hatzair , Habonim Dror , Hechaluz and Akiva and the Jewish Military Association consisting of former members of the Polish army and the youth organization Betar . They were partially supported by the Polish Home Army . On the morning of April 19, 1943, the poorly armed resistance fighters succeeded in repelling the troops that were to dissolve the ghetto on the orders of Ferdinand von Sammern-Frankeneggs , SS and police leader in the Warsaw district. On the same morning, at Heinrich Himmler's instructions , Jürgen Stroop, who had been in Warsaw since April 16, took over command of the German troops. The "major action", as the National Socialists called the military action against the ghetto and its residents, lasted almost a month in total, although only three days had been planned for it. After the fighting had lasted for a few days, the German units began, on Stroop's instructions, to set fire to the buildings of the ghetto in order to drive the inhabitants hiding out of their hiding places. The uprising ended on May 16 with the symbolic demolition of the Great Synagogue , which Stroop later described as a “fantastic piece of theater”. According to Stroop's records, more than 56,000 Jews were killed or deported to extermination camps and murdered there during the uprising .

Creation of the photo

The Stroop Report

During the "major action", Jürgen Stroop sent daily reports on its progress to the Higher SS and Police Leader East Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger , who resided in Cracow , and passed them on to Heinrich Himmler . Kruger suggested that these reports be compiled in a book after the destruction of the Warsaw ghetto was over. According to Stroop's statement, there were three leather-bound editions intended for Himmler, Krüger and himself. The unbound draft remained in the Warsaw headquarters of the SS and Police Leader with Staff Leader Max Jesuiter.

Two copies of the report still exist today. A leather-bound edition is in the possession of the Polish Institute for National Remembrance in Warsaw. Which of the three issues it is could not be clarified beyond doubt. An unbound copy, very likely the draft that remained in Warsaw, is held by the United States' National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

The report is titled There is no longer a Jewish neighborhood in Warsaw! In addition to the 32 daily reports, it contains a list of those killed and wounded on the part of the German troops and a summary of the events. The text is followed by a collection of photographs entitled “Photo Report”. It contains 53 photos each. However, only 37 photos are included in both copies, but some of them differ in their arrangement and size. The scenes from three other photos are part of both editions, but taken from different perspectives and at slightly different times.

The photo of the boy is included in both copies. In the Warsaw copy it is the 14th photo, in the NARA copy it is in the 17th position. In the Warsaw copy, like all the other photos, it is mounted on bristol cardboard with a frayed edge. It is 17.75 × 12.5 centimeters, with a white border around 5 millimeters wide. The caption "Bred out of bunkers by force" was written by hand in Sütterlin script directly on the box below the picture. In the NARA copy, it is one of only three photographs that are not attached to frayed Bristol cardboard, but are on cardboard with straight edges. The photo was photographed together with the caption and a reproduction was stuck on. The overall size of the photo paper is 19.7 × 15.6 centimeters, the photo is 17.2 × 11.2 centimeters. It is slightly cut off at the left, right and top edge compared to the version of the Warsaw copy.

There are indications that the boy's photo was not only used for the Stroop report, but also for other purposes during the final years of the Nazi era . In the collection of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum , for example, there is one of the boy's photo under thirty lead plates for making copies of photos showing the Nazi persecution of the Jews. George Kadish , a Lithuanian photographer and survivor of Kauen concentration camp , found the plates in an antiquarian bookshop after the end of World War II and handed them over to the museum in 1991. When and how the boy's photo plate was made is unclear. What it was used for is also unknown.

photographer

It has not yet been possible to clarify who took the photos of the Stroop report and especially the photo of the boy. There are various details about this. According to Sibyl Milton, several photographers who are believed to have been members of the Propaganda Company (PK) 689 and the department for machine reporting of the Todt Organization were responsible for the photos . In 1982, at the request of the New York Times , she named PK 689 Arthur Grimm as a possible photographer of the boy's photo. According to the historian Christoph Hamann , however, Grimm was only supposed to have been to Warsaw in 1939 and then to have been deployed to the front in Greece, the Balkans and the Soviet Union, and is thus out of the picture. In Grimm's inheritance in the Prussian Cultural Heritage picture archive, which has only been handed down in gaps, there are neither positives nor negatives of the photo.

A 1968 article in the British Sunday Times named Albert Cusian, another member of PK 689, as the photographer of the photo. A reporter for the newspaper had interviewed Cusian, who was then living in a small German town near the Danish border. This is said to have confirmed that he had taken the famous photo.

According to the Polish researcher Magdalena Kunicka-Wyrzykowska, the photos were taken by members of the security police and SS-Obersturmführer Franz Konrad , who was responsible for the so-called “valuation”, ie the confiscation of Jewish property. However, she does not name a source for this. Konrad himself had claimed in the 1951 trial against him and Stroop that he had photographed the murder of Jews in the Warsaw ghetto in order to incriminate Stroop in a report secretly sent to Hitler . However, it is unclear whether these photos, if Konrad's statement is correct, are part of the Stroop report. According to Karl Kaleske, who was Stroop's adjutant in Warsaw , the photographs are said to have been taken by members of the security police .

description

The black and white photo shows a larger number of people. The exact number is difficult to determine because many of them can only be seen obscured and the image becomes blurred towards the rear. While the educator Annette Krings speaks of around 20 people, the media scientist Richard Raskin identifies a total of 25 people in the photo. The following information is essentially based on his analysis of the photo.

Five German soldiers (12-16) can be seen in the photo. They guard the other 20 people, all of them civilians, who as a column leave a house through a gate that leads onto a street. Among them are four children, a girl (22) and three boys (18, 24, 25). A male youth (19) can also be seen. Of the adults, Raskin identified seven as women, with only three (17, 20, 23) being clearly identifiable. The faces of the other four women (1, 6, 8, 9) are partially covered. The eight men (2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 10, 11, 21) wear hats, two women (6, 17) wear headscarves. The civilians are dressed in coats and jackets, the men wear trousers, the women skirts. Two women (17, 20) can see white armbands that they wear on their right arm. All civilians whose hands can be seen raise at least one of them, indicating that they are surrendering. Many of them carry bags or sacks of various kinds with them. So they were apparently able to pack up some of their belongings before they were captured by German troops.

While Christoph Hamann sees a lot of movement in the group of prisoners, for Richard Raskin they seem to be standing still. Only raised feet can be seen at the bottom left. Raskin therefore suspects that the convoy was stopped to take the picture. The caption of the photo in the Stroop report, “Taken out of bunkers by force” does little to match the impression conveyed by the photograph. So there is no inner image evidence of such a violent process, such as messy or dust-covered clothing. Due to the good condition of the prisoners, the Polish historian Andrzej Żbikowski suspects that the photo was taken in the first days of the uprising, before the Germans started setting fire to the ghetto houses.

Among the prisoners, the little boy in the foreground stands out. He stands a little apart from the rest of the people who are standing in a semicircle around him. He wears a coat and shorts as well as knee socks and sturdy shoes. Unlike the other people pictured, his bare knees can be seen. He looks in the direction of the photographer, but does not look directly at him. Fear, helplessness and sadness are clearly visible on his face, while the faces of the other prisoners show tension and resistance. Only the girl in the front left (22) looks directly at the photographer, the other prisoners look in different directions. So the slightly taller boy (24) looks to the left at something outside the photo, the woman in the foreground throws her gaze back, whether the little boy (25) or the German soldier (16) is unclear.

Among the five German soldiers, the one to the right of the little boy (16) stands out. He is the only one of the five who is not covered by other people. Since it is also illuminated by sunlight, it can be seen more clearly than the others. Like these, he wears a helmet, but only with him there are motorcycle goggles. He also holds a submachine gun, the barrel of which is pointed roughly at the lower left part of the boy's coat. The soldier behind him (15) is also carrying a weapon, but only a very small part of it can be seen. It is particularly noticeable that the soldier (16) seems to be looking directly into the camera. His posture also gives the impression of posing for the photographer while the other soldiers appear as if they were not aware that they were being photographed. Richard Raskin also sees a serenity displayed in the soldier, through which he appears as the one who has the authority and can decide the fate of the prisoners.

The photo was probably taken in daylight. The light that seems to come from the top left illuminates mainly the right foreground and the boy's hat (25). The soldier with the weapon (16) and the left half of the face of the people in the column are also illuminated by the light.

Identity of the people in the photo

boy

The identity of the boy in the foreground is not clear. Since most of the children from the ghetto had already been deported, the historian Peter Hayes assumes that the child was the child of an employee of the Jewish ghetto administration or someone close to them, as it was possible to save them from being deported . Richard Raskin presents in his book four people who believed themselves to be the boy or who were mistaken for him by others, and gives the sources for these claims: Artur Dąb Siemiątek, Issrael Rondel, Tsvi C. Nussbaum and Levi Zeilinwarger. The Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial also lists Ludwik Simonsohn as a possible name for the boy on its website, without giving any sources.

Artur Dąb Siemiątek

The first name that came up as a possible identity of the boy was Artur Dąb Siemiątek (often also: Artur Domb Siemiontek). According to Edward Kossoy of the Jerusalem Post , two women are said to have declared independently of one another in the 1950s that the boy, who was born in 1935 in Łowicz , was in the picture. This claim was boosted in 1977 and 1978: in January 1977 it was confirmed in a statement by Jadwiga Piesecka, sister of Artur Dąb Siemiątek's grandfather, and in December 1978 her husband Henryk Piasecki testified in Paris . In the meantime, in July 1978, various international newspapers had taken up the thesis. Richard Raskin found reports in the French newspaper L'Humanité , the British Jewish Chronicle and the Danish newspapers Ekstra Bladet and Århus Stiftstidende . They did not appear as signed articles, only as captions for the photography. The Ekstra Bladet claimed that Siemiątek was alive and living in a kibbutz in Israel. The edition of the Århus Stiftstidende , published the following day, quoted the French press agency AFP , according to which Siemiątek's relatives had declared that he had died in Warsaw in spring 1943.

Issrael Rondel

In response to the report in the Jewish Chronicle , in which Artur Dąb Siemiątek was introduced as the boy in the photo, a businessman from London contacted the newspaper and claimed that he was the boy, not Siemiątek. Although he asked to remain anonymous, the British tabloid News of the World revealed his identity. While the newspaper called him Issy Rondel, he is listed as Issrael Rondel on the Yad Vashem website and Israel Rondel on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website . In the interview, Rondel stated that the photo was taken in 1941. However, this is considered rather unlikely. He also claimed not to have worn socks when the photo was taken. The boy in the photo is wearing knee socks. This was not evident from the section of the photo that was printed in the Jewish Chronicle . In addition, there are a few other statements in the interview that make the credibility of Rondel's report appear questionable from Richard Raskin's point of view.

Tsvi walnut

1982 declared Tsvi Nussbaum , an otolaryngologist from New City , in an article in the New York Times that he believed to be the boy in the photo. Nussbaum was born in Palestine in 1935 , and his family moved to Sandomierz in Poland in 1939 . After his parents were murdered by the National Socialists in 1942, he came to live with his uncle and aunt in Warsaw, who were hiding in the “Aryan” part of the city. In July 1943, two months after the end of the ghetto uprising, the two went to the Hotel Polski with Tsvi Nussbaum after hearing of rumors that the Germans would provide passports to Jews born abroad to enable them to travel to Palestine . From there they were taken to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp on July 13th . Tsvi Nussbaum remembered that during the evacuation a soldier asked him to raise his hands, but not to a photographer, and did not recognize any of the other people in the photo. There are still other aspects that speak against him being the boy in the photo. The historian Lucjan Dobroszycki of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research points out in an article in the New York Times that the Jews probably would not have worn white armbands with the Star of David outside the ghetto. Her thick clothes speak for a shot from May rather than July. The soldiers' combat clothing goes better with a shot during the uprising. In addition, all other photos of the Stroop report were taken in the Warsaw ghetto. In addition, the 13th of July mentioned by Nussbaum as the recording time is almost two months after the date assumed for the completion and dispatch of the Stroop report. A comparison of a passport photo of Nussbaum from 1945 with the boy in the photo also speaks against Nussbaum's statement. Nussbaum has free earlobes , but the boy's earlobes in the photo seem to have grown.

Levi Zeilinwarger

In 1999, the then 95-year-old Avraham Zeilinwarger from contacted Haifa that the kibbutz lohamei hageta'ot resident Ghetto Fighters' House and declared the boy in the photo is his 1932 born son Levi. He later added that the woman to the left of the boy (23) was his mother Chana Zeilinwarger. The photos of Levi and Chana that were available to Richard Raskin are not suitable for comparison with the boy shown in the photo due to their low resolution. Thus the statement cannot be checked. Avraham Zeilinwarger was a slave laborer in Warsaw until he fled to the Soviet Union in 1940. The fate of his wife, son and daughter Irina is unclear. Zeilinwarger assumes that they died in concentration camps in 1943 .

Other prisoners

For other prisoners seen in the photo, various people said that they recognized relatives in them. The girl on the left of the picture (22) identified Esther Grosbard-Lamet, who lives in Miami Beach , in 1994 as her niece, Hanka Lamet, who was born in Warsaw in 1937. According to Yad Vashem, she was murdered in the Lublin-Majdanek concentration and extermination camp . According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the woman next to the girl (20) is her mother, Matylda Lamet Goldfinger. The young person with the white sack (19) was identified by Hana Ichengrin as her brother Ahron Leizer Kartuzinsky. Yad Vashem also mentions Harry-Haim Nieschawer as a possible name for the boy. Golda Shulkes, who lives in Victoria , Australia , recognized her grandmother Golda Stavarowski in the woman (17) in the background.

Josef Blosche

The only person in the picture who has been unequivocally identified is the soldier (16) on the right in the picture with the MP28 submachine gun . It is about the SS Rottenführer Josef Blösche . During his stationing in the Warsaw Ghetto, he was distinguished by particular brutality. Several survivors reported indiscriminate shootings that he carried out on his tours through the ghetto. He was often accompanied by SS-Untersturmführer Karl Georg Brandt , the head of the Jewish department at the Commander of the Security Police and SD in the Warsaw district, and SS-Oberscharführer Heinrich Klaustermeyer . After the end of the war, Blösche settled in Urbach , Thuringia , where he worked as a miner. In the course of the investigation into Ludwig Hahn , commander of the security police in Warsaw during the war, the Hamburg public prosecutor's office issued an arrest warrant for Blosche in 1965. This put the GDR authorities on his track and led to his arrest in January 1967. In 1969 he was the Erfurt District Court for war crimes and crimes against humanity, sentenced to death and in July in the central place of execution in Leipzig per shot in the neck executed. Just one day after his arrest, Blosche had admitted to being the man in the photo. He later described the events depicted in the photo in more detail and stated that the prisoners had been taken to the transshipment point , from where they had been taken to the Treblinka extermination camp. This contradicts Blösche's statement from the 1969 trial that he never accompanied a transport to the transshipment point. But since Blosche admitted his involvement in mass shootings , Richard Raskin speculates that the prisoners in the photo may have been shot in the ghetto.

Blosche can be seen in three other photos from the Stroop report. On a photo with the caption The evacuation of a company is being discussed , he is standing on the left with a submachine gun in his hand. In another photo, he stands together with Heinrich Klaustermeyer and Karl Georg Brandt in front of a group of prisoners who are referred to as rabbis in the caption . Presumably they are Orthodox Jews . On a third photo, Blosche can be seen together with Stroop and Klaustermeyer.

- More photos of the Stroop report showing Blosche (title from the Stroop report)

analysis

National Socialists' intention

The Higher SS and Police Leader Ost Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger Stroop explained the general function of the photographs of the ghetto uprising for the National Socialists in an interview:

“Photographs of the large-scale action will serve as invaluable tools for the future historians of the Third Reich, for the Führer, for Heinrich Himmler, for our nationalist poets and writers, as SS training material and, above all, as evidence of the burden and the sacrifices made by the Nordic countries Races and Germany had to produce in order to free Europe and the world from the Jews. "

According to Annette Krings, the special intention behind the creation of the photo of the boy is made clear by the chosen caption "Bringed out of bunkers by force". So it is supposed to document the lawful arrest of people. The choice of perspective for the photo is also consistent with this: the photographer was probably standing on a raised level, which was why he photographed the boy from above in particular. In contrast, Josef Blösche seems to be looking down at the photographer in the background. The purpose of the recording is therefore to “record the power of the perpetrators and the impotence of those arrested”. This is also the case with the other photographs from the Stroop report. Only two photos show residents of the ghetto as actors, on one two of them appear as informers , another shows a resident on the run jumping out of a burning house.

In addition to this division into “powerful Germans” and “powerless Jews”, Richard Raskin sees another division that the photo should make. So it is likely that Stroop wanted to differentiate himself from other, "weaker" National Socialists with this photo. It could have served as evidence that Stroop had managed what others were unable to do because of pity or other weaknesses (from the National Socialist point of view): killing women and children. In addition to this glorification of one's own heartlessness, the photo conveys an obligation, as Krüger had already expressed through his statement. Through their own deeds, the extermination of the Jews, future generations would be spared this task, for which one expects gratitude and admiration.

Reasons for the iconization of the photo and the boy

The number of surviving photographs documenting the Holocaust is enormous. In 1986 , Sybil Milton spoke of more than two million photos that were in the archives of more than 20 nations. This did not take into account the extensive collections in archives of the Soviet Union , which were opened after its collapse, so that the number of photos is likely to be significantly higher today. In comparison, however, the number of images used in publications is small. The photo of the boy from the Warsaw Ghetto is one of the best known and most frequently used photographs of the Holocaust. The reasons for this iconization are described in various analyzes . An important property of the photo that contributed to its dissemination is the physical integrity of the people portrayed. This distinguishes it from many other images that show dead, emaciated or otherwise suffering people. This makes it possible to look at the photo without painful sensations. In addition, from the point of view of Christoph Hamann , who refers to Lessing 's Laokoon or beyond the boundaries of Mahlerey and poetry , it favors identification with the victims, which would have been made much more difficult by a more ugly depiction. According to Lessing, it is also important not to show “the utmost”. For Hamann, this is the case with the boy's photo, as no gas chambers or firing pits are shown, for example . Despite this generally cautious depiction, the photo gives Richard Raskin the impression that the physical integrity of the prisoners is only a snapshot and should not have lasted long. The strong contrasts created by the depiction of victims and perpetrators in a photo are also an important aspect for the iconization of the photo.

There are also compositional reasons for the widespread use of the photo. The boy's head is roughly at the point where the horizontal and vertical lines of the golden section meet. According to Annette Krings, the diagonal formed by the column of prisoners contradicts common viewing habits and thus creates tension. In addition, unlike many snapshots of laypeople, the edges of the image are included in the composition, which suggests a skilled photographer. Richard Raskin also sees the large number of people depicted as one of the reasons for the success of photography, as it allows the viewer to focus his attention on a variety of different faces and postures.

Despite this diversity, a large part of the photo's perception is concentrated on the little boy in the center of the picture. The picture is usually described as the photo of the boy from the Warsaw ghetto, although he is only one of more than twenty people shown. The focus of attention on him led Marianne Hirsch to the assessment that the boy had become the "model child of the Holocaust". In addition to the above-described positioning at the intersection of the lines of the golden section, the boy is also highlighted in other ways. So the other people form a semicircle around him. While the other prisoners stand close together, the boy seems isolated from the group. He is also the only one in the photo whose look can be described as fearful. This makes him, together with the raised hands framing his face, the center of attention of the viewer. His raised hands, a gesture belonging to the world of soldiers and completely unusual for children, make the enormity of the scenery in the photo particularly clear.

Effects on perception of the Holocaust

The choice of photographs used to depict the Holocaust has an impact on how posterity will perceive it. The boy's photograph shows the Jews at the moment of defeat as victims who surrendered. The fighting that took place during the uprising is not shown. In this way, according to Annette Krings, photography helps to partially implement the Nazis' intended extermination of the Jews by not showing them as active and resistant people, but only as those who were persecuted and murdered. This victimization is often aided by the captions used. Christoph Hamann shows that in many school books that use photography, the reference to the ghetto uprising is suppressed. In addition, verbal passive constructions in the description of the picture often ensured that the perpetrators disappeared. This in turn is also supported by the choice of the image section. There are some prints in which the soldiers on the right are left out. Even if the perpetrators are portrayed, they are limited to members of the SS, which, according to Krings, ignores any possible responsibility of the majority population. This makes it easier not to have to shed light on one's own or family involvement in the National Socialist crimes.

reception

War crimes trials

The first public mention of the photo took place on November 21, 1945, the second day of the Nuremberg Trials of Major War Criminals . United States' lead prosecutor, Robert H. Jackson , referred to the Stroop report in his opening statement and also mentioned a specific photo:

“It is characteristic that one of the captions explains that the photograph concerned shows the driving out of Jewish 'bandits'; those whom the photograph shows being driven out are almost entirely women and little children. "

“It is characteristic that one of the captions explains that the photograph described shows the driving out of Jewish 'bandits'; the people in the photo are almost all women and small children. "

In contrast to other captions, the caption of the boy's photo does not mention bandits, but the mention of women and children makes it clear that Jackson meant this photo. In no other photo in the Stroop report are almost exclusively women and children to be seen. Despite the explicit mention of Jackson, the boy's photo was not among the five photos projected on a screen on December 14, 1945 in the trial. According to Annette Krings, the reason for this could have been the supposed harmlessness of the photo and its consequent weaker evidential value for the atrocities of the National Socialists, one of the characteristics that contributed to its later popularization . The boy's photo was one of the 18 selected photos that appeared together with the Stroop report in Volume 26 of the official report of the International Military Tribunal on the Nuremberg Trial of Major War Criminals.

The photo was also mentioned in the trial against Adolf Eichmann , which took place between April and December 1961 before the Jerusalem District Court. So it said in the opening statement of the chief prosecutor Gideon Hausner :

“We shall submit to the Court Jürgen Stroop's report, which begins with these words: 'There are no Jewish habitations left in Warsaw.' We shall also submit to you the photographs which he attached to his report - the famous photograph of the little child standing with his hands up (he too an enemy of the Reich!) And the picture of the girl fighters with the shadow of death in their eyes. "

“We will present Jürgen Stroop's report to the court, which begins with these words: 'There is no longer any Jewish residential area in Warsaw.' We will also present you with the photographs he attached to his report - the famous photograph of the little child standing with his hands raised (he, too, an enemy of the Reich!) And the image of the young women fighters with the shadow of death in their eyes . "

The other photo from the Stroop report mentioned by Hausner shows three captured young resistance fighters and is only included in the Warsaw copy of the report. The caption there reads: "Women of the Haluzzen movement captured with weapons", which refers to the Zionist youth organization Hechaluz . According to Dorothy P. Abram, Hausner wanted to clarify the innocence of Eichmann's victims by referring to the boy's photo and in particular the exclamation that he was also an enemy of the Reich. This use of children murdered in the course of the Holocaust as symbols of innocence ran through the entire process. Hausner described the children as "the soul of this charge".

Documentation material, non-fiction and school books

One of the first publications to contain the photo of the boy from the Warsaw Ghetto was the book The Third Reich and the Jews by Léon Poliakov and Joseph Wulf, published in 1955 . A crucial year for the popularization of the photo was 1960. That year it appeared in Germany in a facsimile edition of the Stroop report. It was also part of the book The Yellow Star by Gerhard Schoenberner , one of the first comprehensive collections of images of the Holocaust. While the German edition shows the photo of an old woman with a Jewish star , the cover of the Dutch edition, published in the same year, shows the photo of the boy. The British, French and Canadian editions published years later also show the photo on their cover. Also in 1960, the exhibition The Past Warns was presented in the Berlin Congress Hall , which was devoted to the persecution of Jews since the Middle Ages. The boy's photo was on the poster for the exhibition. If the exclusive use of the photo on the poster was originally planned, a portrait photo of Albert Einstein was added to the left half at the pressure of the exhibition advisory board . While Harald Schmid sees it as a symbol for the happy German-Jewish era, for Christoph Hamann Einstein symbolizes the scientific, technological and social progress of mankind, which is threatened by National Socialism. Since 1960 the photo has appeared on the covers of several other books about the Holocaust and National Socialism, including the information brochure The Holocaust from the Yad Vashem memorial.

The first use of the photo in a school book can be proven in 1958. Since then it has illustrated many other school books from the Federal Republic and the GDR . In Austria, too, the photo is often used in history textbooks that deal with National Socialism.

media

Newspapers also used the photo to illustrate their articles. The US magazine Life used it in 1960 to illustrate excerpts from Adolf Eichmann's memoirs . That same year it appeared in the New York Times Magazine over an interview with Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion about the upcoming Eichmann trial . There was no reference to the Warsaw Ghetto or the Ghetto Uprising in the caption. In 1993 the New York Times published an article comparing the Bosnian war with the Holocaust. The photo of the boy from the Warsaw ghetto was juxtaposed with a recent photo from Bosnia.

Several articles were also devoted to the photo itself. Over the years, for example, the Jerusalem Post alone published three articles that report on the symbolic power of the photo. Time magazine included the photo in its "100 Most Influential Photos of All Time" collection. Besides a photo by the Soviet photojournalist Dmitri Baltermanz , which shows a German massacre in Kerch on the Crimean peninsula, it is the only photo that documents National Socialist crimes.

science

Media scholar Richard Raskin published A Child at Gunpoint in 2004 , which he says was probably the first book to deal with a single photo. In the book, Raskin devotes himself to the description and analysis of the photo, the origins of the Stroop report and four possible identities of the boy in the photo. In the most extensive chapter, Raskin presents four selected works that take up the photo, dispensing with his own comments and instead presents interviews with people who were involved in the creation of the works. In the last chapter, too, in which he describes several cases in which the photo was used in connection with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict , he refrains from analyzing it himself.

In 2009, L'Enfant juif de Varsovie by the historian Frédéric Rousseau was published . Building on Raskin's research, Rousseau dedicates himself to the history of the creation and reception of the photo.

Dan Porat's book The Boy was published in 2011; it presents the life stories of five people who are connected with the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. In addition to the stories of Tsvi Nussbaum and a young person named Rivka, the stories of the National Socialists Jürgen Stroop, Josef Blösche and Franz Konrad are examined. According to the reviewer Patricia O'Sullivan, it is difficult to categorize his book since Porat, according to his own statement, filled the gaps that arose during his research with “a priori imagination ”.

In 2020 the book Holocaust Icons in Art: The Warsaw Ghetto Boy and Anne Frank by the Israeli art scholar Batya Brutin was published. In it, the author dedicates herself to the processing of the boy from the Warsaw ghetto and Anne Franks in art.

The photo was also examined in specialist articles, including two by literary scholar Marianne Hirsch on photographs of the Holocaust. The German-language history didactics also devoted extensive research to the photo. In 2006 the book The Power of Images by the teacher Annette Krings was published, in which the author examines the role of historical photographs of the Holocaust in political education. The photo of the boy from the Warsaw ghetto serves as a central case study. The history didactician Christoph Hamann devoted several articles to the photo and its importance for history lessons.

art

Visual arts

In September 1982 the Portuguese newspaper Expresso published a caricature by António Moreira Antunes , which adapted the photo. All prisoners wear a Palestinian scarf on their heads, while the soldiers' helmets have a Star of David , which means that they are assigned to the armed forces of Israel . The cartoon was in response to the Sabra and Shatila massacre , in which Lebanese Maronite Catholics killed several hundred Palestinians in two refugee camps in Beirut . At that time, the camps were surrounded by Israeli troops, but they did not intervene. The cartoon won the Grand Prize of the International Salon of the Cartoon in Montreal in 1983 . Representatives of the Canadian Jewish Congress sharply criticized the award. The caricature is “artistically dishonest, morally obscene and intellectually indecent” and a “slander of the Holocaust”. These allegations were rejected by members of the jury. However, Christoph Hamann is also very critical of the caricature. So she instrumentalizes the Holocaust for a perpetrator-victim reversal and ignores the “context of the Holocaust as a racist-biological program for the extermination of the Jews”. A very similar cartoon by the Belgian Gal also appeared in the Flemish newspaper De Nieuwe in 1982 . Only the boy wears a Palestinian shawl on it. The face of Josef Blösche has been replaced by the face of the Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin , the SS man in the background who comes through the gate appears as US President Ronald Reagan . The cartoon sparked protests from readers, some of whom canceled their subscriptions.

As part of their Holocaust project, the American artist created Judy Chicago in 1991 with her husband, photographer Donald Woodman, the panel in / Balance of Power (German: Un / balance of power ). Five photographs of suffering children from different phases of the 20th century are each juxtaposed with a painting depicting the world of adults. The children are portrayed as victims, the mostly male adults as perpetrators. The cut-out in the middle shows the boy from the Warsaw Ghetto. At his side, Chicago painted a caricature of a German soldier aiming his large gun straight at the boy's chest. Another photo shows a section of The Terror of War by Nick Út , which shows the Vietnamese girl Phan Thị Kim Phúc , who was seriously injured by a napalm attack . He is faced with a bomber pilot aiming his bombs at the girl. Christoph Hamann criticizes Chicago's work for putting the Holocaust on an equal footing with other forms of child oppression and thus denying its singularity . For this reason, it is also very controversial in the Jewish community.

The Lithuanian artist and Holocaust survivor Samuel Bak began processing the boy in the photo into paintings in the mid-1990s, which are part of the larger Landscapes of Jewish Experience project . On them Bak shows the boy, whom he describes as “the most symbolic of all Holocaust images”, in connection with well-known iconographic motifs such as the crucifixion , the felled tree of life or depictions of life in concentration camps. The boy's face is replaced by other faces, including that of the artist himself. Since 2008, Bak's depictions of the boy have been grouped under the title Icon of Loss .

In 2003, the Israeli artist Alan Schechner processed the photo in the video installation The Legacy of Abused Children: from Poland to Palestine . In it he combined it with a photo taken in April 2001 during the Second Intifada of a Palestinian boy who was led away by them after he had pelted stones at Israeli soldiers. In the photo you can see that the fearful looking boy has wet himself. Schechner's work initially shows the photo of the boy from the Warsaw ghetto. He is holding a photo that, after zooming in with the camera, can be recognized as the photo of the Palestinian boy. He in turn holds the photo of the boy from the Warsaw ghetto in his hand, which is also zoomed in.

The graphic Yellow Badge by the Australian artist Jennifer Gottschalk was shown for the first time in 2008 in the exhibition The Holocaust Yellow Badge in Art . For her, Gottschalk used names of victims of the Holocaust in 1692, from which she composed two other yellow stars in addition to the silhouette of the boy, who, in contrast to the original, wears a yellow star, the words "Jude" and "Juif" (French for " Jew ”).

literature

The poet and Holocaust survivor Peter Fischl dedicated the poem To the Little Polish Boy With His Arms Up to the boy in the photo , which he wrote in 1965 but did not publish until 1994. Since Fischl did not have the photo when he wrote the poem and only had to trust his memory of it, it contains some errors. This is how Fischl describes a Star of David on the boy's coat, which cannot be seen there. He also writes that many of the Nazis' machine guns were aimed at the boy, although in reality there was only one machine gun pointing at him. Fischl initially distributed the poem on a poster along with an edited version of the picture. A large Jewish star had been added to the boy's coat to match the description in the poem. Since Fischl offered the poster together with information material for teachers and the project thus gave a more scientific than artistic impression, Dorothy P. Abram sees this processing critically. Fischl later used a version of the photo without the Jewish star.

The author and artist Yala Korwin, who was born and raised in Poland and also survived the Holocaust, dedicated a poem to the boy in the photo. The Little Boy With His Hands Up , which she wrote in 1982 and published in her book To Tell the Story in 1987 , is written from the you perspective. With this rather unusual narrative form, through which Korwin seems to speak directly to the boy, she said she wanted to keep the boy alive. Korwin illustrated the poem with his own drawing, which shows the boy tall in the foreground and Josef Blosche and the man standing behind him small in the background.

The satirical play The Patriot ( Hebrew הפטריוט) by the Israeli writer Hanoch Levin , which was performed for the first time in Israel in 1982, took up the photo in the first version. In one scene, the main character Lahav points his weapon at Mahmud, an Arab boy whose surrender pose is reminiscent of that of the boy from the Warsaw ghetto. Meanwhile, Lahav speaks to his mother and explains that Mahmud will atone for her blood and that of her slain family. Then he quotes a song that his mother's little brother sang when a German soldier pointed his gun at him. The mention of the German soldier was removed from the play by the censorship authority. The brother's song is sung by Mahmud instead. Then he is shot by Lahav.

In the 1988 novel Umschlagplatz by the Polish author Jarosław Marek Rymkiewicz , the narrator first describes the photo and then compares it with a photo of himself that was taken around the same time. The narrator gives the boy's name as Artur Siemiątek.

Movie and TV

The first publication that presented the photo to a broad world audience was the French documentary Night and Fog by director Alain Resnais from 1956. It was shown in a sequence about the construction of concentration camps for four seconds.

In Ingmar Bergman's feature film Persona from 1966, one of the two protagonists, Elisabet Vogler, played by Liv Ullmann , finds the photo in a book, leans it against a lamp and looks at it. This is followed by 14 settings that show the entire photo as well as individual sections.

The photo plays a role in the final episode of the six-part BBC series The Glittering Prizes , which first aired on February 25, 1976. The young Jewish writer Adam Morris, played by Tom Conti , visits the clothing store of Carol Richardson, his brother's girlfriend (played by Prunella Gee ), to buy a present for his wife. In the course of the conversation, Adam shows her a section of the photo on which the boy's face can be seen with his hands raised. Carol's question as to whether he is the boy, Adam denies and explains that it is a six year old "Yid" (negative connotation English term for Jew) on the way to what is good for him. In addition, the photo shows the afterlife for him . According to Frederic Raphael , the series' writer, what Adam means by this is that Jews should expect something bad to happen to them rather than good.

In 1985 Mitko Panov, a Macedonian student at the State University of Film, Television and Theater Łódź , shot the six-minute short film Z podniesionymi rękami (also known as With Raised Hands ). The film shows the process of taking the photo. After the wind has blown his cap off the boy's head, he looks briefly at the cameraman and the soldier and then runs after the cap. As the wind blows it several times, the boy moves further and further away from the scene. When he finally gets hold of the cap, he puts it on and continues to flee from the recording. At the end of the film, he disappears behind a wooden fence. Shortly afterwards you can see his cap being thrown up over the fence and falling back to the ground. Then it is thrown again and disappears from the picture. The original photo can be seen in the background of the subsequent credits. The film won several awards, including the Palme d'Or for best short film at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival .

In 1990, the Finnish TV broadcaster MTV and the French broadcaster Gamma TV produced the documentary Tsvi Nussbaum: A Boy from Warsaw . It deals with the life of Tsvi Nussbaum and his claim that he is the boy in the photo. In addition to Nussbaum, relatives and acquaintances, a historian has a say. The film, which neither confirms nor rejects Nussbaum's claim, also addresses other aspects of the photo, for example Josef Blösche and the trial against him.

Comic

In the comic album Hitler. The genocide of the draftsman Dieter Kalenbach and the writer Friedemann Bedürftig from 1989, the little boy is shown in connection with the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. One text reproduces the boy's inner monologue, which is about a secret passage that he does not want to reveal. Jürgen Stroop is also shown in the comic. The boy in the photo also appears in the comic album Auschwitz by Frenchman Pascal Croci , published in 2005 .

Holocaust deniers

The fact that the photo is considered one of the symbolic images of the Holocaust made it interesting for Holocaust deniers . They mostly referred to publications considering the possibility that the boy in the photo might have survived and interpreted them as confirmation of their conspiracy theories . The French Holocaust denier Robert Faurisson, for example , triumphantly took up Issrael Rondel's claim that he was the boy and saw it as proof that the Holocaust was a myth . In an article he stated that the boy was not killed in an "alleged" concentration camp, as always assumed, but instead lived in London and was "extremely rich". Rondel's statement that he only escaped the Germans after his arrest because he and his mother were able to convince them not to be Jews, so distorted Faurisson that the racist motives of the National Socialists were completely left out. Alfred Schickel commented on Rondel's claims in an article in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . In it he claimed that the probable killing of the boy conveyed in German school books had now turned out to be a lie. In the following editions of the FAZ some letters to the editor appeared in which the authors asked whether the Holocaust was just a myth.

The article in which Tsvi Nussbaum said that he might be the boy in the photo was picked up by the British Holocaust denier David Irving . Irving writes that the boy now lives as a doctor in New York and that only the soldier (meaning bloke) is dead. He was suggesting that the boy's possible survival also meant that none of the prisoners in the photo were killed. The American Holocaust denier Mark Weber dealt with the statements of the historian Lucjan Dobroszycki, who was skeptical about Nussbaum's claims and wanted a more responsible handling of the photo. Weber accused Dobroszycki in an article in the pseudoscientific Journal of Historical Review of wanting to ban historical truths in order not to diminish the emotional impact and usefulness of the photo.

World document heritage

In 2017, UNESCO included the Stroop Report in its World Document Heritage at the suggestion of Poland . The photo of the boy is the only image in the report that is part of the nomination form, explaining the contradiction between the depicted scene and the caption. The page showing the boy's photo also serves to illustrate the entry for the report on the UNESCO website.

literature

Monographs

- Dorothy P. Abram: The Suffering of a Single Child: Uses of an Image from the Holocaust . Dissertation at Harvard University Graduate School of Education, Cambridge 2003 (English, proquest.com ).

- Batya Brutin: Holocaust Icons in Art: The Warsaw Ghetto Boy and Anne Frank . De Gruyter Oldenbourg - Magnes, Berlin / Boston - Jerusalem 2020, ISBN 978-3-11-065691-6 , doi : 10.1515 / 9783110656916 (English, accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- Annette Krings: The power of pictures. On the significance of historical photographs of the Holocaust in political education work (= Wilhelm Schwendemann , Stephan Marks [Hrsg.]: Erinnern und Lern. Texts on human rights education . Volume 1 ). Lit, Berlin / Münster 2006, ISBN 3-8258-8921-1 .

- Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. A Case Study in the Life of a Photo . Aarhus University Press, Aarhus 2004, ISBN 87-7934-099-7 (English).

- Barbie Zelizer: About to Die. How News Images Move the Public . Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-975213-3 , pp. 138–143 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

Single item

- Christoph Hamann : "The turn to the subject". To the photo of the boy from the Warsaw Ghetto in 1943 . In: History in Science and Education . Journal of the Association of History Teachers in Germany . Volume 51, No. 12 , 2000, pp. 727-741 .

- Christoph Hamann: Change frame. Narrativizations of key images - the example of the photo of the little boy from the Warsaw ghetto . In: Werner Dreier, Eduard Fuchs, Verena Radkau, Hans Utz (eds.): Key images of National Socialism. Photo- historical and didactic considerations (= concepts and controversies. Materials for teaching and science in history - geography - political education . Volume 6 ). Studienverlag, Innsbruck / Vienna / Bozen 2008, ISBN 978-3-7065-4688-1 , p. 28-42 .

- Christoph Hamann: The boy from the Warsaw ghetto. The Stroop Report and the Globalized Iconography of the Holocaust . In: Gerhard Paul (ed.): The century of pictures. 1900 to 1949 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2009, ISBN 978-3-525-30011-4 , p. 614-623 .

- Marianne Hirsch : Projected Memory: Holocaust Photographs in Personal and Public Fantasy . In: Mieke Bal , Jonathan Crewe, Leo Spitzer (Eds.): Acts of Memory: Cultural Recall in the Present . University Press of New England, Hanover / London 1999, ISBN 0-87451-889-X , pp. 3–23 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- Marianne Hirsch: Nazi Photographs in Post-Holocaust Art: Gender as an Idiom of Memorialization . In: Alex Hughes, Andrea Noble (Ed.): Phototextualities. Intersections of Photography and Narrative . University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque 2003, ISBN 0-8263-2825-3 , pp. 19–40 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- Sebastian Schönemann: Cultural image memory and collective image experience. The visual semantics of memory using the example of the photo of the boy from the Warsaw ghetto . In: Journal for History Didactics . Volume 12, No. 1 , September 2013, p. 46–60 , doi : 10.13109 / zfgd.2013.12.1.46 ( academia.edu ).

- Ewa Stańczyk: The Absent Jewish Child: Photography and Holocaust Representation in Poland . In: Journal of Modern Jewish Studies . Volume 13, No. 3 , 2014, p. 360-380 , doi : 10.1080 / 14725886.2014.951536 (English).

Web links

- Petra Mayrhofer: Boy from the Warsaw Ghetto. In: Online module European Political Image Memory. September 2009 .

- The Boy in the Photo? on the website of the Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team

- German soldiers pointing guns at women and children during the liquidation of the ghetto on the Yad Vashem website

- Jews captured by SS and SD troops during the suppression of the Warsaw ghetto uprising are forced to leave their shelter and march to the Umschlagplatz for deportation on the website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Individual evidence

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 58.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 58-59.

- ^ A b Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 60.

- ^ Kazimierz Moczarski: Conversations with an Executioner . Ed .: Mariana Fitzpatrick. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs 1981, ISBN 0-13-171918-1 , pp. 164 (English). Quoted in: Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 54.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint . 2004, p. 26.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint . 2004, pp. 30-31.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint . 2004, p. 29.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 49.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 52-53.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 177–178, with illustration.

- ^ A b Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint . 2004, p. 31.

- ↑ a b c d e David Margolick : Rockland Physician Thinks He Is the Boy in Holocaust Photo Taken in Warsaw . In: The New York Times . May 28, 1982 (English, nytimes.com ).

- ↑ a b c Christoph Hamann: The boy from the Warsaw ghetto. 2009, p. 616.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint . 2004, p. 32.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 13.

- ↑ a b c Annette Krings: The power of pictures. 2006, p. 81.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 12.

- ^ A b c Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 14.

- ^ A b Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 16.

- ↑ Christoph Hamann: "The turn on the subject". 2000, p. 734.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 16-17.

- ^ Mariusz Nowik: Only the oppressor has a name. The story of the boy from the picture. In: TVN24 website . April 19, 2018, accessed August 16, 2019 .

- ↑ Annette Krings: The power of pictures. 2006, p. 82.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 95.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 13-14.

- ↑ Annette Krings: The power of pictures. 2006, p. 82.

- ↑ Peter Hayes: Why? A story of the Holocaust . Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2017, p. 224 ff.

- ↑ a b c German soldiers pointing guns at women and children during the liquidation of the ghetto. In: Yad Vashem's website. Retrieved May 4, 2019 .

- ^ Edward Kossoy: The Boy from the Ghetto . In: The Jerusalem Post . September 1, 1978, p. 5 (English). Quoted in: Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint . 2004, pp. 98-99.

- ^ A b Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint . 2004, pp. 99-100.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint . 2004, p. 83.

- ^ Clay Harris: Warsaw Ghetto Boy-Symbol of The Holocaust . In: The Washington Post . September 17, 1978 (English, washingtonpost.com ).

- ↑ a b Jews captured by SS and SD troops during the suppression of the Warsaw ghetto uprising are forced to leave their shelter and march to the Umschlagplatz for deportation. In: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website. Retrieved May 4, 2019 .

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 83-85.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 85, 100.

- ↑ Sue Fishkoff: The Holocaust in one photograph . In: The Jerusalem Post . April 18, 1993 (English). Quoted in: Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 87-88.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 87.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 88.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Guntpoint. 2004, p. 90.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 92-93.

- ^ A b c Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 93-94.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 94-95.

- ↑ Norbert F. Pötzl: The worst of all . In: Der Spiegel . No. 19 , 2003, p. 58–59 ( spiegel.de [PDF; 189 kB ]).

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 98.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 96-98.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 96-97.

- ^ Kazimierz Moczarski: Conversations with an Executioner . Ed .: Mariane Fitzpatrick. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs 1981, pp. 151 (English): “Photographs of the Grand Operation will serve as invaluable tools for future historians of the Third Reich - for the Führer, for Heinrich Himmler, for our nationalist poets and writers, as SS training materials and above all, as proof of the burdens and sarcrifices endured by the Nordic races and Germany in their attempt to rid Europe and the world of the Jews. " Quoted in: Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 26.

- ↑ Annette Krings: The power of pictures. 2006, pp. 87-88.

- ↑ Annette Krings: The power of pictures. 2006, pp. 58-59.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint . 2004, p. 79.

- ^ Sybil Milton: Photographs of the Warsaw Ghetto . Annual volume No. 3. Simon Wiesenthal Center, 1986 (English, Photographs of the Warsaw Ghetto ( Memento from June 6, 2016 in the Internet Archive )).

- ↑ Annette Krings: The power of pictures. 2006, p. 89.

- ^ A b Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 19.

- ↑ Christoph Hamann: Change frame. 2008, p. 30.

- ^ A b Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 21.

- ↑ Annette Krings: The power of pictures. 2006, pp. 84-86.

- ^ Marianne Hirsch: Nazi Photographs in Post-Holocaust Art: Gender as an Idiom of Memorialization. 2003, p. 19.

- ↑ Herman Rapaport: Is There Truth in Art . Cornell University Press, Ithaca 1997, ISBN 0-8014-8353-0 , pp. 200 (English). Quoted in Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 15-16.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint . 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint . 2004, pp. 19-20.

- ↑ a b Annette Krings: The power of pictures. 2006, p. 115.

- ↑ Christoph Hamann: Change frame. 2008, p. 32.

- ↑ Christoph Hamann: "The turn on the subject". 2000, p. 740.

- ^ Trial of the Major War Criminals before the International Military Tribunal . tape 2 . International Military Court , Nuremberg 1947, p. 126 (English, loc.gov [PDF; 20.7 MB ]).

- ^ A b Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 34.

- ↑ Annette Krings: The power of pictures. 2006, p. 98.

- ^ Trial of the Major War Criminals before the International Military Tribunal . tape 26 . International Military Court, Nuremberg 1947 (English, loc.gov [PDF; 28.1 MB ]).

- ^ The Trial of Adolf Eichmann Sessions 6-7-8 (Part 6 of 10). In: Nizkor Project . Archived from the original on August 26, 2000 ; accessed on July 26, 2019 (English).

- ^ Dorothy P. Abram: The Suffering of a Single Child: Uses of an Image from the Holocaust. 2003, pp. 173-174.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 105-106.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 106, 156.

- ↑ Harald Schmid: "The past warns". Genesis and reception of a traveling exhibition on the Nazi persecution of the Jews (1960-1962) . In: Journal of History . tape 60 , no. 4 , 2012, p. 331-348 , here: 339-340 . Quoted in: Sebastian Schönemann: Cultural image memory and collective image experience. 2013, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Christoph Hamann: Change frame. 2008, p. 33.

- ^ Marianne Hirsch: Nazi Photographs in Post-Holocaust Art: Gender as an Idiom of Memorialization. 2003, p. 20.

- ^ Christoph Hamann: Appropriation of history through photography . In: History, Politics and their Didactics. Historical Education Journal . tape 31 , no. 1-2 , 2003, pp. 28–37 , here: 29 . Quoted in: Annette Krings: The Power of Images. 2006, p. 99.

- ↑ Martin Krist: “There is no longer a Jewish residential area in Warsaw”. The iconic image of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in high school classes . In: Werner Dreier, Eduard Fuchs, Verena Radkau, Hans Utz (eds.): Key images of National Socialism. Photo- historical and didactic considerations (= concepts and controversies. Materials for teaching and science in history - geography - political education . Volume 6 ). Studienverlag, Innsbruck / Vienna / Bozen 2008, ISBN 978-3-7065-4688-1 , p. 140–150 , here: 140 .

- ↑ Barbie Zelizer: About to Die. 2010, p. 139.

- ↑ Barbie Zelizer: About to Die. 2010, p. 141.

- ↑ Barbie Zelizer: About to Die. 2010, p. 140.

- ^ The Most Influential Images of All Time. In: Time. Retrieved July 21, 2019 .

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint . 2004, p. 5.

- ↑ Oren Baruch Stier: A Child at Gunpoint: A Case Study in the Life of a Photo, Richard Raskin (Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press, 2004), 192 pp., Pbk. $ 33.00 . In: Holocaust and Genocide Studies . tape 20 , no. 2 , 2006, p. 309-311 , doi : 10.1093 / hgs / dcl006 (English).

- ^ Frédéric Rousseau: L'Enfant juif de Varsovie. Histoire d'une photography. Le Seuil, 2009, ISBN 978-2-02-078852-6 (French).

- ↑ Jean-Louis Jeannelle: “L'Enfant juif de Varsovie. Histoire d'une photography ”, de Frédéric Rousseau: l'enfant du ghetto. In: Le Monde . January 8, 2009, accessed June 22, 2019 (French).

- ↑ Kathryn Berman: The Boy: A Holocaust Story - Dan Porat. In: Yad Vashem's website. Retrieved June 22, 2019 .

- ↑ Patricia O'Sullivan: The Boy: A Holocaust Story. In: Historical Novel Society website. February 2012, accessed June 22, 2019 .

- ↑ Batya Brutin: Holocaust Icons in Art: The Warsaw Ghetto Boy and Anne Frank. 2020.

- ^ Marianne Hirsch: Projected Memory: Holocaust Photographs in Personal and Public Fantasy . 1999. Marianne Hirsch: Nazi Photographs in Post-Holocaust Art: Gender as an Idiom of Memorialization. 2003.

- ↑ Annette Krings: The power of pictures. 2006.

- ↑ Christoph Hamann: "The turn on the subject". 2000. Christoph Hamann: Change frame. 2008.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 162-163.

- ↑ Michael Solomon: Anti-Israel Cartoon Wins Prize . In: Jewish Telegraphic Agency (ed.): JTA Daily News Bulletin . tape LXI , no. 138 , July 21, 1983 ( jta.org ).

- ↑ Michael Solomon: CJC Protests Award-winning cartoon; Says It Defames the Holocaust . In: Jewish Telegraphic Agency (ed.): JTA Daily News Bulletin . tape LXI , no. 139 , July 22, 1983 ( jta.org ).

- ↑ Christoph Hamann: Change frame. 2008, p. 35.

- ↑ Kjell Knudde: Gal (Gerard Alsteens). In: Lambiek Comiclopedia. Retrieved July 14, 2019 . Picture at roularta.be.

- ^ Im / Balance of Power. In: Judy Chicago website. Retrieved May 25, 2019 .

- ↑ Christoph Hamann: Change frame. 2008, pp. 33-35.

- ^ Sarah Jenkins: Judy Chicago Artist Overview and Analysis. In: TheArtStory.org. January 21, 2012, accessed June 22, 2019 .

- ↑ Samuel Bak: About my art and me . In: Samuel Bak, Eva Atlan, Peter Junk, Uta Gewicke (eds.): Samuel Bak. Life after . Museum and Art Association, Osnabrück 2006, ISBN 3-926235-26-8 , p. 9–18 , here: 14 . Quoted in Sebastian Schönemann: Cultural image memory and collective image experience. 2013, p. 55.

- ^ Marianne Hirsch: Nazi Photographs in Post-Holocaust Art: Gender as an Idiom of Memorialization. 2003, p. 27.

- ↑ Sebastian Schönemann: Cultural image memory and collective image experience. 2013, p. 55.Destiny M. Barletta (Ed.): Icon of Loss: Recent Paintings by Samuel Bak . Pucker Art Publication, Boston 2008 (English, squarespace.com [PDF; 4.3 MB ]).

- ^ Alan Schechner: The Legacy of Abused Children: from Poland to Palestine. In: dottycommies.com. 2003, accessed on May 25, 2019 .

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 166-168.

- ^ Michael Rothberg: From Gaza to Warsaw: Mapping Multidirectional Memory . In: Criticism . tape 53 , no. 4 , 2011, p. 523-548 , here: 536-538 , doi : 10.1353 / crt.2011.0032 , JSTOR : 23133895 (English).

- ↑ Sebastian Schönemann: Cultural image memory and collective image experience. 2013, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Dorothy P. Abram: The Suffering of a Single Child: Uses of an Image from the Holocaust. 2003, pp. 72-73.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 118.

- ^ Dorothy P. Abram: The Suffering of a Single Child: Uses of an Image from the Holocaust. 2003, p. 184.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 164.

- ^ David K. Shipler: Arab and Jew. Wounded Spirits in a Promised Land . Penguin, Harmondsworth 2002, pp. 316 (English). Quoted in Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 164.

- ^ Marianne Hirsch: Projected Memory: Holocaust Photographs in Personal and Public Fantasy. 1999, pp. 3-4.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 105.

- ^ Peter Ohlin: The Holocaust in Ingmar Bergman's Persona. The Instability of Imagery . In: Scandinavian Studies . tape 77 , no. 2 , 2005, p. 241-274 , here: 252-253 , JSTOR : 40920587 (English).

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 107-113.

- ↑ Mitko Panov: With Raised Hands . In: Richard Raskin (Ed.): Pov A Danish Journal of Film Studies . No. 15 , March 2003, p. 8 (English, au.dk [PDF; 1.7 MB ]).

- ↑ Jeffrey Shandler: While America Watches. Televising the Holocaust . Oxford University Press, New York / Oxford 1999, ISBN 0-19-511935-5 , pp. 197–198 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Christoph Hamann: The boy from the Warsaw ghetto. 2009, p. 620.

- ↑ Christoph Hamann: Change frame. 2008, p. 28.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 85-86.

- ↑ Alfred Schickel: Teachers and students are the victims . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . August 19, 1978. Quoted in: Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 86-87.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, p. 87.

- ^ Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. 2004, pp. 91-92.

- ↑ Mark Weber: The 'Warsaw Ghetto Boy' . In: Journal of Historical Review . tape 14 , no. 2 , 1994, p. 6–7 (English, historiography-project.com ).

- ↑ a b Jürgen Stroop's Report. In: UNESCO website. Accessed August 11, 2019 .

- ↑ Nomination form International Memory of the World Register Raport Jürgena Stroopa There is no Jewish residential area - in Warsaw anymore! (There is no more Jewish district in Warsaw!). (PDF; 339 kB) In: UNESCO website. P. 8 , accessed on August 11, 2019 .