Friedrich Stoltze

Friedrich Stoltze (born November 21, 1816 in Frankfurt am Main ; † March 28, 1891 there ) was a German poet and writer . He was a journalist and publisher in Frankfurt am Main and throughout his life campaigned for the national unification of Germany and for a democratic and republican state. Although most of his work consists of political writings, especially as editor of the satirical magazine Frankfurter Latern , he is remembered by the public in his hometown primarily for his poems in the Frankfurt dialect .

Live and act

parents house

Stoltze's father was the innkeeper Friedrich Christian Stoltze (1783–1833). He came from Hörle in the Principality of Waldeck and came to Frankfurt am Main in 1800, where he initially worked as a waiter in the Württemberger Hof . In 1808 he married the bourgeois daughter Anna Maria Rottmann (1789–1869) and acquired Frankfurt citizenship. Initially still working in the business of his father-in-law, who ran the Zur goldenspitze inn in Mausgasse, in 1813 he became tenant of the Zum Rebstock inn at the foot of the cathedral tower . It was considered a meeting place for liberal-minded citizens. Friedrich Stoltze saw the light of day in 1816 as the seventh child of his parents in the northeast of the total of six independent houses in the courtyard at the southern end of Kruggasse , the house at Im Rebstock 4 . A memorial plaque on the house at the cathedral reminds of the demolition of the house where he was born in 1904 in order to build Braubachstrasse .

Four of Friedrich's older siblings died shortly after birth, his sister Sabine in 1819 at the age of nine. He developed a close relationship with his older sister Annett (1813-1840). My sister is responsible for being a poet! I wash my hands in innocence . He was particularly influenced by his grandfather Friedrich Rottmann , who had come to Frankfurt from Neckarbischofsheim and developed into a Frankfurt patriot there. In his story Von Frankfurts Macht und Große Friedrich Stoltze set a literary monument for him: If aaner had the biggest sticker on his Vatterstadt, it was my grandfather ... And from all these history and wise teachings it comes from me that I Such a successful Frankfort child, I am body and soul on my Vatterstadt.

Stoltze received a good upbringing, among others by Friedrich Karl Ludwig Textor , a cousin of Johann Wolfgang Goethe , and whose comedy Der Prorector, written in 1794, is considered the earliest surviving theater piece in Frankfurt dialect. Stoltze later wrote that he counted himself in the family as part of the dialect-speaking Frankfurt parliamentary group , consisting of his mother and himself, while the Waldecker parliamentary group , his father and his sister, spoke High German.

The enlightened pastor and school reformer Anton Kirchner , who had baptized him in the Katharinenkirche and who taught him as a confirmand in 1830, had a great influence on Stoltze . In that year, Stoltze's spiritual poems were written , but also the first natural poems that were influenced by Goethe's youthful poetry.

He got on less well with the strict Pietist rector Johann Theodor Vömel , who at that time was the head of the municipal high school , which Stoltze also attended. Vömel dismissed his natural poems as Abominable Spinozerei , whereupon his father forbade him from all further poetic attempts.

Stoltze got to know the liberal and democratic movements of the Vormärz very early on . The vine became a refuge for Poles in exile around 1830 . The young Friedrich Stoltze was shaped by house searches and arrests he witnessed. Later he wrote about it: The Gasthaus zum Rewestock was in kääner very serene grace with our very highest republican rule and my father was name was written with red ink and a blue note in front in the black Bollizeibuch. The Gasthaus zum Rewestock was the main bar of the former Frankfurt demagogue.

His father took him to the Hambach Festival in 1832 , where he got in touch with Ludwig Börne , whose liberal thoughts influenced him. After the Frankfurt Wachensturm on April 3, 1833, his sister Annett was sentenced to a fine for participating in the funeral of a fallen insurgent and to a four-week prison term for attempting to free the imprisoned fraternity member Heinrich Eimer , which she only received after the birth of her illegitimate son Friedrich Philipp had to start on December 12, 1834.

Poet and writer

Stoltze was initially supposed to learn a commercial profession and in 1831 had been apprenticed to the Frankfurt merchant Melchior, who ran his office in the house to the red man at the Fahrtor . Marianne von Willemer lived in the same house , who encouraged his poetic talent and wanted him to give up the unpopular teaching. After his father's death in November 1833, Stoltze was free to make decisions, but the family's financial situation deteriorated. His mother was only able to keep the inn and the associated mineral water trade for a short time. In 1834 she leased the vine and at the beginning of 1837 moved with her children first to Schnurgasse and later to Bornheim .

Friedrich continued his interrupted business training from 1838 to 1840 in Paris and Lyon. His 1838 in Lyon Resulting Federal Song of the Germans in Lyon was by Felix Mendelssohn set to music. After his return to Frankfurt in 1841, his first volume of poetry was published. The Frankfurt merchant Marquard Georg Seufferheld then hired him as a private tutor . Seufferheld wanted to introduce the educational concept of the kindergarten in Frankfurt and therefore sent Stoltze to study with Friedrich Fröbel in Bad Blankenburg and Keilhau for two years , in 1844 at the University of Jena .

His son Carl Adolph Retting, born out of wedlock in Mainz in 1842, came from his love affair with the Frankfurt bourgeois daughter Maria Christina Retting (1816–1843), which he began in 1837 . The child was born in secret and grew up with foster parents in Enkheim , because Christina's father strictly rejected the connection with the democratically minded poet. Maria Christina Retting, whom he enthusiastically called Lyda , died on August 21, 1843 in Frankfurt while Stoltze was in Blankenburg. How pale are the stars now, How cloudy my eyes! It died a long way off to me, my dear Stoltze wrote. After the death of his mother, Carl Adolph was taken care of by his grandmother Anna Maria Rottmann . It was not until 1864, after his father's civil existence had been secured, that Carl Adolph Retting was able to take on his father's name. He became a well-known theater poet under the name of Adolf Stoltze .

After his return to Frankfurt in 1845, Stoltze temporarily read aloud to the Frankfurt banker Amschel Mayer von Rothschild . As an occasional poet for upscale Frankfurt society, he had access to influential circles, which made him known to the public and generated income, including as a theater librettist. In 1845 he met the Katholisches Montagskranzchen , a German Catholic circle, the Steindecker daughter Marie Messenzehl (born June 23, 1826, † August 4, 1884), whom he called Mary . The Catholic girl and the thick-headed Lutheran , according to their own perception , unconcernedly violated any convention. Their illegitimate son Friedrich Richard was born on August 31, 1846, but he died that same year. The second son Heinrich was born on April 16, 1848 . On November 15, 1848, he acquired Frankfurt citizenship, which required a certain amount of property.

When the couple on April 10, 1849 in the St. Catherine married, Mary was pregnant for the third time. The wedding was the first mixed marriage in Frankfurt with the blessing of the Evangelical Church . Stoltze later wrote mockingly: A pastor did indeed marry us, but Lutheran-diabolical, And God was not edified by it, because God is strictly Catholic. And what particularly bends me down, because it deserves blows: The children of all that we produce, Are children, oh, love! By 1861 the couple had 11 children, four of whom died as infants.

He took a lively interest in the German Revolution of 1848 and the Frankfurt National Assembly . On September 18, 1848, the September riots broke out , in which the MPs Felix von Lichnowsky and Hans von Auerswald were murdered by insurgents in front of the Friedberger Tor . A state of emergency was declared after heavy barricade fighting. One day later a guard at the Konstablerwache arrested Stoltze and the composer Heinrich Neeb who was accompanying him . The two had made themselves suspicious of their gymnastic hats. They were only released after a police interrogation.

The failure of the imperial constitution and the imperial deputation in April 1849 turned into a serious disappointment for Stoltze. After the outbreak of the uprising in the Palatinate, he followed his friend and later partner Ernst Schalck to report from there as a war correspondent . In the summer of 1849 he returned to Frankfurt. His plan to found his own newspaper, however, could not be realized at first, and the publication of his now numerous poems was delayed. When Nicolaus Hadermann founded the Volksblatt für Rhein und Main in December 1849 , Stoltze soon became an avid collaborator. At the end of 1850, together with the publisher Karl Knatz, he prepared the publication of a Frankfurter Sonntagsblatt , of which only one number appeared (on January 1, 1851).

Since the restorative zeitgeist hindered the development of a political newspaper, Stoltze turned to his humorous and dialect skills. In the carnival season of 1852, on February 3rd, he published the first edition of his Frankfurter Krebbel- and Warme Broedscher newspaper . 10,000 copies were sold on the very first day, 12 Kreuzers each .

Up to 1879 a total of 44 issues appeared at irregular intervals, mainly with glosses on current affairs in the Free City of Frankfurt and in Germany. The Frankfurt authorities were tolerant, but not the neighboring Frankfurt states of Hesse and Kurhessen , in which he was soon wanted in a wanted list, so that he was only safe within the boundaries of the Free City of Frankfurt. In 1859 he narrowly escaped arrest during a spa stay in Königstein im Taunus in Nassau , as an extradition agreement existed between Nassau and Hesse . In his short story The Flight from Königstein he described this incident.

The Frankfurt lantern

In 1860 he founded the liberal-democratically oriented weekly newspaper Frankfurter Latern based on the model of the Berlin Kladderadatsch . In his satirical texts, which were illustrated by Schalck, Albert Hendschel and at times also by Wilhelm Busch , he targeted current events and did not spare even high-ranking personalities. Typical for the Latern were the jumping jacks , stories about the typical Frankfurt petty bourgeois jumping jack , and the dialogues between Millerche and the Berjerkapitän . All of these figures were taken from Carl Malß's comedies.

The lantern soon reached large numbers, but was persecuted by the censors outside Frankfurt because of its often anti-Prussian stance. After the Prussian annexation of the city, the editorial office was occupied on July 21, 1866 and Stoltze had to flee from occupied Frankfurt. After stays in Switzerland and Stuttgart, he returned to his hometown after an amnesty and on January 1, 1867, he started working again with his new newspaper “Derreal Jacob”. He kept his (fictional) staff, already known from the “Latern”: Mr. Hampelmann, Millerche and Berjerkapitän put the critical texts in Stoltze's mouth. From July 30th, “The true Jacob” appeared with the subtitle Ridentem dicere verum (“Smiling to tell the truth”), but within five years only 32 editions could pass the Prussian censorship. Stoltze received support from the citizens of Frankfurt who were critical of Prussia and who had previously subscribed to the “Frankfurter Latern” and who were now buying the “True Jacob”.

Only after the establishment of the German Empire and the Peace of Frankfurt in 1871 did Stoltze's situation improve. From January 1, 1872, "Die Frankfurter Latern" could appear again regularly until his death. Nevertheless, he repeatedly came into conflict with the censorship authority. Politically, Stoltze stood up for the national unity of Germany, for democracy and the republican form of government throughout his life. He was convicted several times of offenses against the press or lese majesty . He did not belong to any political party, but supported the Frankfurt MP Leopold Sonnemann and the German People's Party in the election campaigns for the German Reichstag .

At his death in 1891, Stoltze was the most popular and most famous Frankfurt resident after Johann Wolfgang von Goethe . His grave is in the Frankfurt main cemetery . For Stoltze's 200th birthday in 2016, a large anniversary program was held with numerous exhibitions, readings, lectures, theater performances and a ceremony in the Kaisersaal .

Stoltze's literary estate, consisting of manuscripts, over 650 letters, around 600 books, a private photo album and other personal items, is kept in the Johann Christian Senckenberg University Library.

The family

His illegitimate son Carl Adolph from the connection with Christine Retting grew up with his grandmother Anna Maria Stoltze after the death of his mother. Only at the age of 22 could he take his father's name in 1864; under the name Adolf Stoltze he became a famous stage poet in his hometown. Among other things, he created the Schwank Alt-Frankfurt , in which he set a monument to the Society of the Free City. He died very old on April 19, 1933 in Frankfurt.

The following children came from Friedrich Stoltze's marriage to Mary Messenzehl:

- Friedrich Richard (born August 31, 1846 - † November 6, 1846)

- Heinrich (April 16, 1848 - September 6, 1872 in Scott City , Missouri ). Heinrich emigrated to America in 1868. He first worked on a farm near Cleveland , then moved to St. Louis as a casual laborer 150 miles on foot . There he leased an 80- acre farm from Lisette Dick in 1871 , to whose niece he became engaged. He wanted to grow sugar cane and raise chickens there, but soon died of a lung disease.

- Christian Ernst, born May 24, 1849; † November 23, 1849. Friedrich Stoltze wrote: You should have stayed with us, to be happiness and comfort to us, but you wanted to become a dear angel.

- Lyda (born July 20, 1850 - † January 27, 1930). The eldest daughter was named after the nickname of Stoltze's first lover. Like her younger sisters, she had a very close relationship with her father and remained unmarried throughout her life. Lyda became a teacher in Liège and later a private teacher with the Guaita family .

- Christian (1851-24 December 1854)

- Ferdinand (14 October 1853 - December 1853)

- Laura (May 28, 1855 - September 5, 1945). The second daughter may have been named after Laura Sigismund , with whom Stoltze had a brief relationship after the death of his lover and before returning to Frankfurt. Together with her sister Molly, Laura sifted through and arranged the estate of her father Friedrich Stoltze and handed it over to the Frankfurt City Library and the Historical Museum .

- Molly (1856 - January 10, 1910). She married as the only daughter, in 1886 with Franz Schreiber (1850–1901), who worked as an editor for the Frankfurter Latern and for the Kleine Presse . Her sons Friedrich and Eduard were Stoltze's only grandchildren from his marriage to Mary, but there were others, the children of his above-mentioned illegitimate son Adolf Stoltze.

- Alice (January 24, 1858 - 1926)

- Hermann (born January 17, 1860 in Königstein im Taunus , † 1899 in Tübingen ) was born shortly before Stoltze's hasty escape from Königstein. He developed into a problem child among Stoltze's sons, who accused him of his unreliability. He was prone to alcoholism and broke off several apprenticeships until he finally completed an apprenticeship as a landscape gardener in Hanau. In 1883 he moved to London to become self-employed. Later, the relationship with his father improved again, especially since Hermann was also successful in his career. He died as head gardener in Tübingen.

- Friedrich (born June 6, 1861; † March 16, 1880 in Fluntern , Zurich ). Friedrich was Stoltze's favorite son. He attended the model school in Frankfurt and studied mathematics in Karlsruhe and Zurich. He was considered extraordinarily talented, but died of typhoid shortly after starting his studies . His death hit his father hard. He wrote two months later: Not all are dead whose hills rise! We love, and what we loved lives. That lives until our own life melts away. Not all are dead who are buried. These words are also carved on Stoltze's tombstone in Frankfurt's main cemetery.

Apartments

The Stoltze family lived in numerous apartments in Frankfurt over the years. After moving from the Rebstock, he lived with his widowed mother first in Schnurgasse, later in Bornheim and in Schäfergasse . After his return from Thuringia, he first took an attic apartment in Tollgasse (today Börsenstraße), then in Große Friedberger Straße .

After the wedding with Mary Messenzehl, the family lived on Große Bockenheimer Straße , later on Papageigasse and Klostergasse, where the first Krebbel newspaper appeared in 1852 . In the 1850s the family moved to the then still rural Röderbergweg , later they lived in the city again: Am Schaumainkai , Bornwiesenweg , Pfingstweide and Sandweg .

After his return from exile in 1866, he found accommodation for a year in the Zickwolff country house on the Mühlberg , which the Frankfurt banker Heinrich Bernhard Rosenthal made available to him. Just one year later he moved to Bäckerweg , in 1869 to Unterlindau 10 and finally in 1873, on the mediation of Baron Rothschild, to the Stoltzehäuschen at Grüneburgweg 128. The classicist garden house of the Rothschilds was demolished in 1930 for the construction of the IG-Farben house .

Frankfurt poem

His most famous poem, Frankfurt , was published in 1880 to greet visitors to the fifth German Gymnastics Festival in Frankfurt. It is a song of praise for the hometown, which, precisely because of its unmistakably ironic undertone, has remained Frankfurt's most popular poem to this day. Its opening lines in particular are often quoted:

- There is no city in the wide world

- who please as much as my Frankfort,

- And I don't want to get into my head:

- how can nor e man be from Frankfort!

Prizes and awards after Stoltze

- Since 1985, the Frankfurter Latern Association , which is reminiscent of Stoltze's main work of the same name, has awarded the lantern prize to personalities who have made very different contributions to the tradition of the Frankfurt dialect author, journalist and satirist Friedrich Stoltze. Among other things, the director Wolfgang Kaus and the actor Hans Zürn were honored, who “supported the work of the Stoltze Association and enhanced it acoustically. With your Stoltze programs and revues you have made Stoltze's works audible and freed them from the dust between two book covers. "

- The Frankfurt citizen Johannes Lueg donated the Friedrich Stoltze Prize , which has been awarded every two years by the Association of Friends of Frankfurt since 1978 to people who have made particular contributions to the city's cultural heritage. The winners of the Stoltze Prize so far have included Liesel Christ , Lia Wöhr , Johann Philipp von Bethmann , Jutta W. Thomasius and Robert Gernhardt .

- The Stoltzestrasse in the east of Frankfurt city center and the Stoltzeschneise in the Frankfurt city forest between Oberschweinstiege and Goethe Tower are named after Stoltze .

- Since 1992, a previously unnamed square in downtown Frankfurt between Katharinenkirche and Holzgraben has been called Friedrich-Stoltze-Platz . The Stoltze Fountain from 1895 was located on the square from 1981 to 2016 , and was re-erected in September 2017 as part of the Dom-Römer project on the chicken market , its original location.

- The Friedrich-Stoltze-Schule in Frankfurt was a primary and secondary school in the Seilerstraße at Friedberger Tor from 1934 to 2010 . It was merged with the Gerhart Hauptmann School to form the Ludwig Börne School . The former school building has been empty since then.

- The Friedrich-Stoltze-Schule is a secondary and secondary school in Königstein im Taunus . It has been named after the poet since 1997.

Stoltze Museum

1978 taught Polytechnic Society , the Stoltze Museum of Frankfurter Sparkasse in the former Schönborner Hof in Töngesgasse a 34-36. The exhibits included image documents, texts and furniture from his estate and that of his son Adolf Stoltze . In 2010, on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the lantern, an exhibition was opened in the museum with the title And it burns! shown. This was followed in the same year by an exhibition on the last two years of the Frankfurter Latern before it was closed on March 25, 1893. An exhibition about Heinrich Keller (1816–1884), the Frankfurt publisher Stoltzes, followed in 2013 .

In 2014, the museum moved to the Frankfurter Sparkasse customer center in Neue Mainzer Strasse due to construction work . In 2019 the Stoltze Museum moved into its new premises in Haus Weißer Bock on Markt 7 . The new museum building was built as part of the Dom-Römer project . The neighboring house of the Goldene Waage is exactly opposite the Rebstock farm on the market , where Stoltze's birthplace was, and across from the chicken market with the Stoltze fountain .

Works

Editions of works published during his lifetime

- Poems in High German dialect , Verlag Heinrich Keller, Frankfurt am Main 1862

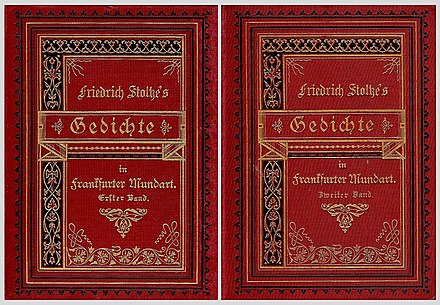

- Poems in Frankfurt dialect in two volumes , Verlag Heinrich Keller, Frankfurt am Main 1865/1871

- Poems in Frankfurt and High German dialect , Verlag Heinrich Keller, Frankfurt am Main 1871

- Novellas and stories in Frankfurt dialect , (two volumes), Verlag Heinrich Keller, Frankfurt am Main 1880/1885

Later editions

- Collected Works . 5 volumes. Heinrich Keller, Frankfurt am Main 1892 ff.

- Mixed fonts . Heinrich Keller, Frankfurt am Main 1896.

- Fritz Grebenstein (Ed.): Friedrich Stoltze, works in Frankfurt dialect . 4th edition. Waldemar Kramer, Frankfurt am Main, 1990, ISBN 3-7829-0394-3 .

- Henriette Kramer (ed.): The most beautiful poems in Frankfurt dialect. 5 volumes. Waldemar Kramer, Frankfurt am Main, 1997–1998, ISBN 3-7829-0472-9 / ISBN 3-7829-0473-7 / ISBN 3-7829-0483-4 / ISBN 3-7829-0484-2 / ISBN 3- 7829-0485-0 .

literature

- WB : Friedrich Stoltze's collected works. Frankfurt a. M. 1892. Publishing house by Heinrich Keller . In: The new time . Review of intellectual and public life . 10.1891-92, 2nd vol. (1892), no. 52, pp. 822-824. Digitized

- Otto Hörth: Stoltze, Friedrich . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 36, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1893, pp. 415-419.

- Sabine Hock : Stoltze, Friedrich. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 25, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-428-11206-7 , p. 428 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Wolfgang Klötzer (Hrsg.): Frankfurter Biographie . Personal history lexicon . Second volume. M – Z (= publications of the Frankfurt Historical Commission . Volume XIX , no. 2 ). Waldemar Kramer, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-7829-0459-1 , p. 442-445 .

- Johannes Proelß: Friedrich Stoltze, Ein Bürger von Frankfurt , revised by Günther Vogt, Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1978, ISBN 3-7973-0327-0

- Association of Friends and Supporters of the Stoltze Museum (ed.): "O freedom, my everything, my luck and my woe ...": Work and life of the writer Friedrich Stoltze , Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1997

- Petra Breitkreuz: Friedrich Stoltze. Poet - thinker - democrat. Waldemar Kramer, Wiesbaden 2016, ISBN 978-3-7374-0466-2 .

Web links

- Wolfgang Klötzer and Petra Breitkreuz: Stoltze, Friedrich in the Frankfurter Personenlexikon

- Literature by and about Friedrich Stoltze in the catalog of the German National Library

- Stoltze, Friedrich Philipp. Hessian biography. (As of May 9, 2020). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

References and comments

- ↑ a b Friedrich Stoltze, The red chimney sweep

- ^ Hessische Familienkunde , Volume 25, Heft 6, Sp. 379. According to Proelß, Rottmann came from Neckarsteinach , after Grebenstein from Neckargemünd .

- ^ Friedrich Stoltze, Works in Frankfurter Mundart , Verlag Waldemar Kramer, Frankfurt am Main 1961

- ↑ Full text at Wikisource

- ↑ The thoughts are free, but also need a publisher in FAZ of April 9, 2013, page 38

- ^ Information sheet on the new Stoltze Museum on the Frankfurter Sparkasse website, accessed on August 27, 2018

- ↑ The sign is imprecise to the effect that it commemorates a house with the old litera designation L87 that did not exist. In fact, there were only houses L87a and L87b, corresponding to Im Rebstock 4 and Im Rebstock 5 (the diagonally opposite one) ; see. on this: Friedrich Krug: The house numbers in Frankfurt am Main, compiled in a comparative overview of the new with the old, and vice versa . Georg Friedrich Krug's Verlag-Buchhandlung, Frankfurt am Main 1850, p. 135.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Stoltze, Friedrich |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Frankfurt poet, writer and publisher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 21, 1816 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Frankfurt am Main |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 28, 1891 |

| Place of death | Frankfurt am Main |