Königspitze

| Königspitze | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Königspitze from the northwest (Ortler-Hintergrat) |

||

| height | 3851 m slm | |

| location | Border between South Tyrol and the Province of Sondrio , Italy | |

| Mountains | Ortler Alps | |

| Dominance | 3.64 km → Ortler | |

| Notch height | 424 m ↓ Suldenjoch | |

| Coordinates | 46 ° 28 ′ 43 " N , 10 ° 34 ′ 6" E | |

|

|

||

| First ascent | Stephan Steinberger 1854 (possibly first Francis Fox Tuckett , Buxton and the Biner brothers 1864) | |

| Normal way | Firn and ice tour over the southeast ridge | |

|

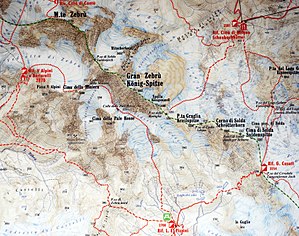

Königspitze and surroundings |

||

The Königspitze (also Königsspitze , Italian Gran Zebrù ) is at 3851 m slm the second highest peak in the Ortler Alps in Italy . Known for its striking shape, the heavily glaciated Dolomite mountain lies on the border between South Tyrol and Lombardy . The fact that Stephan Steinberger was said to have succeeded in making the first ascent in 1854 was doubted for a long time and caused controversy for decades. During the First World War , the Königspitze was of great strategic importance and hotly contested right up to the summit region. In the 20th century the alpine importance of the mountain lay mainly in its north face and the now defunct cornices on the summit ridge, known as the foam roll . Due to the strong glacier retreat and the thawing of the permafrost , mountaineering on the Königspitze is impaired today.

Location and surroundings

The Königspitze is located on the southwestern border between South Tyrol and the Lombard province of Sondrio . It is part of the northern Ortler Alps, more precisely the Ortler main ridge . To the northwest of it lie the Monte Zebrù ( 3735 m ) and the Ortler ( 3905 m ). The Ortler main ridge separates the South Tyrolean Sulden valley with the village of Sulden ( 1843 m ) in the northeast from the Valle di Cedec in the southeast and the Val Zebrù in the southwest, both of which are in Lombardy. This area lies entirely within the Stilfserjoch National Park .

To the north, the Königspitze falls with steep, mostly icy walls down to the Königswandferner , a steep glacier that flows into the Suldenferner below . The Lange Suldengrat , also Mitschergrat, runs west of the Königswandferner . To the west of it, another glacier, the Payerferner, flows to the Suldenferner. The west ridge - actually northwest ridge - of the Königspitze is called Kurzer Suldengrat and runs to the 3427 m high Suldenjoch , the transition to Monte Zebrù. To the west of this pass is the Zebrùferner, which flows south to the Zebrùtal . A side ridge of the Suldengrat runs to the 3408 m high Cima della Miniera and separates the Zebrùferner from the Vedretta della Miniera . Southwest of the Königspitze lies the pre-summit of the Pale Rosse ( 3446 m ), in the north of which the Col Pale Rosse pass ( 3379 m ) connects the Vedretta della Miniera with the Vedretta del Gran Zebrù , which is below the rocky south face . This glacier flows southeast into the Valle di Cedec. The wide, eroded south-east ridge of the Königspitze falls to the 3293 m high Königsjoch , from there the Ortler main ridge continues eastwards to the 3391 m high Kreilspitze . The steep east face of the Königspitze runs north of this ridge down to the eastern part of the Suldenferner.

geology

Like that of Ortler and Monte Zebrù, the summit structure of the Königspitze consists essentially of main dolomite , a shallow-water sedimentary rock of the Upper Triassic , more precisely the Norium . It has the typical, mostly horizontal, but here also folded bank , as it occurs in the nearby Dolomites . In contrast to the rocks there, however, the local dolomite is slightly metamorphic , i.e. it was transformed into dolomite marble in the Upper Cretaceous about 90 million years ago under high pressure and at about 400 ° C (upper green slate facies) . According to modern views of the formation of the Alps, this happened with the northward shift of the present-day Northern Limestone Alps over the Ortler Alps. The rock is therefore not only characterized by its darker, gray color, but also by the lack of fossils , as these were destroyed during the metamorphosis.

In addition, the dolomite of the Königspitze is significantly higher than in most of the other distribution areas of this rock and is therefore subject to a significantly higher degree of frost weathering than the rock of the Dolomites, which is characterized by flowing water. At the Königspitze, the rock has smoother surfaces and great fragility, which makes it less suitable for climbing. Embedded in the main dolomite are several meter thick olisthostromes and layers of calcareous shale. Overall, the dolomite layer here reaches a thickness of up to 1000 meters, which is why it is often assumed that an originally thinner sediment layer has piled up to such a thickness due to multiple thrusts . However, this question has not yet been fully clarified because the Ortler group has still not been adequately investigated geologically. For a long time, geological research was difficult due to the glacier cover, and it was only in the last few decades that more rock was exposed as the glacier retreated.

The Königspitze forms the southeastern end of this Dolomite massif. Just like the foundation of the Königspitze, the neighboring Kreilspitze consists of Veltliner base crystals . This crystalline had already undergone further transformations before the Cretaceous, especially during the Caledonian and Variscan orogeny . It is mainly gneiss , mica schist and phyllite . Between crystalline and dolomite there are sediments ( conglomerates , sandstones and gypsum ) from the Lower Triassic and alpine verrucano from the Permian , but these layers are only a few meters thick.

A special feature of the Königspitze are tertiary dike rocks , more precisely basalt- and diorite-like magmatites , which penetrate the dolomite here due to the proximity to the Periadriatic seam . They are mainly found on the east side of the Königspitze and do not continue in the crystalline below. This indicates that the dolomite layer of the Königspitze was affected by a later shift which cut off these veins. While most of these passages are extremely narrow, the area around the Königsjoch is largely made up of such intrusive rocks . The striking Königsmandl or Kinimandl , a 30 meter high rock tower made of dioritic and tonalitic rocks, also stood here. In 1994, the Kinimandl largely collapsed.

Climate and glaciation

The climate of the Ortler Alps is clearly influenced by the Mediterranean climate and is therefore drier and milder than that in the nearby Central Alps , which shield the Ortler Alps from the precipitation on the north side of the Alps. The annual precipitation barely exceeds 1000 millimeters per year. The snow line here is significantly higher than in the central Alps.

The high degree of icing at the Königspitze is therefore only partly due to the low temperatures at high altitude. The formation of the lower lying glaciers around the mountain, especially the Suldenferner, is more a consequence of the topographical conditions. These glaciers have only small nutrient areas that accumulate precipitation and are largely fed by ice and snow avalanches that descend over the steep flanks. In the flatter terrain below the steep walls, these snow and ice masses can collect to form glaciers. The ongoing rockfall due to the brittle dolomite rock results in a particularly heavy cover of debris , especially on the Suldenferner, which is partially completely hidden under the rock.

The retreat of the glaciers after the Little Ice Age in the Ortler Alps was strikingly different from most other Alpine glaciers, which reached their peak around 1860. On the Suldenferner there was an extremely rapid advance between 1817 and 1819, which even threatened the settlement area of Sulden. Apart from a smaller, further advance in the middle of the 19th century, like the other glaciers in the region, it has since declined almost continuously. Glacier retreat increased at the end of the 20th century. The reasons for this do not lie in greater melting in the glaciers' consumption zone, but rather in a retreat of the nutrient areas up to an altitude of over 3500 m due to the higher summer temperatures. In the lower regions, the thick debris cover protects against melting, so that the glacier here still extends down to about 2500 m , i.e. about 300 meters lower than on the other side of the Suldental valley. The receding of the ice has a major impact on alpinism on the Königspitze, as many classic routes are more difficult and also more dangerous due to the increased risk of falling rocks, so that in some cases they are hardly accessible.

A special feature of the Königspitze was the foam roll , a large cornice on the summit that protruded far beyond the north wall and was frozen into a hanging glacier . Eiswechten of this type rarely form in the Alps and are more known from the Himalayas . Similar cornices have often broken off here and formed anew; the foam roll of the 1950s was considered the largest cornice in the Alps. The foam roller broke off around 1960, but formed anew in the next few years, although this new cornice was less expansive, but more voluminous than the old one. On the night of June 5, 2001, the new foam roll broke off again, with the amount of broken ice estimated at 7000 m³. Since then, new cornices have only slowly formed, it is assumed that the north face, which is less icy today due to global warming, could no longer offer the conditions for a new foam roll.

Flora and fauna

The entire area surrounding the Königspitze is part of the alpine vegetation zone. Forests, including Swiss stone pines , can only be found in the northern Zebrù valley. The end of the valley of the Suldental, which is wooded elsewhere up to a height of 2000 m to 2200 m, is hardly overgrown with trees, which is due to the glacier advance of the Suldenferner in the 19th century, which reached down to the valley floor. The moraine cones , consisting of dolomite rubble, are partially covered by mountain pines , below and especially on crystalline rock, green alder bushes predominate . The alpine rose can often be found in the higher dwarf shrub heather. These heaths and the mats of the alpine vegetation zone show a high biodiversity due to the variety of soils and landforms. The plant community here includes typical west and east alpine species as well as limestone and silicate soils. Particularly rare plants are the leafless and rock saxifrage , the Flattnitz rock flower , the moss bell and the Inntaler primrose . Gentians are common, but edelweiss is rare. The highest-rising flowering plant is the glacier buttercup , in the highest areas only a few mosses and lichens grow .

Chamois and marmots can be found from the tree line up to the glacier borders . The mountain hare is relatively rare here, but the brown hare climbs up to the heights. The predominant predator is the fox , the numbers of which, however, fluctuate greatly, badgers and weasels are less common. The Alpine Ibex was probably exterminated in the 18th century. In the Zebrù Valley in the south of the Königspitze, animals were released back into the wild in the 1960s. The population of several hundred animals is still almost exclusively in this area. The mammal that climbs the furthest is the snow mouse , which can be found in the glacier regions.

The most prominent representative of the bird fauna is the golden eagle , the symbol of the Stelvio National Park. Besides marmots, it hunts mostly snow grouse and hazel grouse . The largest bird of prey, however, is the bearded vulture , which can be found here occasionally. A noteworthy invertebrate in the ice region is the glacier flea , which is particularly common on the Suldenferner.

Surname

In the case of the Königspitze, the part of the name "König" - as with many mountain names containing this word - indicates the function of the mountain as a border point (here to the former Kingdom of Lombardy) as well as its dominant appearance and its striking shape. Because of them, Julius Meurer described Königspitze as the “most perfectly shaped, most elegant mountain in the entire area of the Eastern Alps”. Old and dialectal forms of the name are Königswand or Kiiniwånt , also just König or Kiini . Sometimes this name was used for the entire massif at the head of the Sulden valley.

The translation of the German name, Cima del Re , was also sometimes used in Italian . The current Italian name Gran Zebrù (Big Zebrù) is derived from the Val Zebrù and has an etymologically unclear origin. It is believed that it originated from the pre-Roman word Gimberu for stone pine . Sometimes the word is derived from the Celtic , where it is composed of se (spirit) and bru (castle) and is thus supposed to mean “ghost castle ”. According to this hypothesis, the Celtic faith saw the souls of evil men residing on Monte Zebrù and the royal peak.

Bases and routes

Important mountain huts in the Königspitze area are the Rifugio Pizzini-Frattola ( 2701 m ) in the upper Valle di Cedec and the Rifugio Casati ( Casatihütte , 3254 m ) on the Langenfernerjoch , the transition from the Valle di Cedec to the Martell Valley . To the west of the Königspitze, below the Zebrùferner, is the Rifugio Quinto Alpini ( 2877 m ). In the Sulden valley, the Schaubachhütte ( 2581 m ) and the Hintergrathütte ( 2661 m ), which can be reached with the Sulden am Ortler cable car, are important starting points for climbing the Königspitze.

The Königspitze is accessible from numerous routes , but only a few of them are often used. The normal route can be reached from the Casati or the Pizzini hut and leads from the Vedretta del Gran Zebrù over a steep gully to the southeast ridge and over this to the summit. Difficulty level I (UIAA) must be mastered in the rock . In firn and ice , passages with gradients of up to 42 ° have to be overcome. This route is now considered fragile and prone to falling rocks due to the increasing evacuation in summer , so that a ski ascent is often preferred in spring.

Significant routes on the south side of the Königspitze are the southwest ridge ( Pale-Rosse-Rinne , II, 50 °), the southwest face ( Soldato delle Pale Rosse , III +, 55 °) and Ghost Zebru (V A1, 95 °). On the northwest side, the Kurz Suldengrat (IV-, 60 °) and the Lange Suldengrat / Mitschergrat (IV, 60 °) should be mentioned. The north face, over 600 meters high, is one of the most important north faces in the Eastern Alps. The most frequent ascent is the Ertlweg (IV, 60 °), in addition the western north face (IV +, 60 °), Klimek / Gruhl (IV, 55 °) and Klimek / Grasegger ( Thomas-Gruhl-Gedächtnisführe , IV, 65 °) through the north wall. The route direct exit ( foam roller , 95 °) no longer exists in this form due to the breakage of the foam roller, currently the ice there is about 65 ° steep. On the northeast and east sides, the northeast face ( Minnigerodeführe , 53 °), the east-northeast ridge (III, 50 °) and the east face (also east channel , III, 50 °) should be mentioned. The eastern channel is also used as a route for ski tours in spring . In addition to the ones listed, there are other climbs of subordinate importance that were rarely or never repeated after their first ascent .

Development history

While the nearby Ortler, the highest mountain in the Danube Monarchy, was climbed in 1804, the lower Königspitze remained unnoticed by mountaineers for a long time. The first ascent of the Königspitze in 1854 by Stephan Steinberger is still controversial today. Here, this broke on August 24 of Trafoi and reached for his descriptions of the Stelvio ( 2757 m ), the Passo di Campo ( 3346 m ), the Vedretta di Campo , the Passo di Camosci alto ( 3201 m ), the Passo dei Volontari ( 3036 m ), the Zebrùferner , the Passo della Miniera and the Col Pale Rosse , the southern flank of the Königspitze. As for his further route, it is assumed that he climbed either over the Pale-Rosse-Rinne or on one of the rocky ridges (at that time still covered with firn) next to this steep couloir . He returned the same way and reached the Stilfser Joch at 8 p.m. This route corresponds to a total ascent of 2750 meters of altitude and 1450 meters of descent as well as a horizontal distance of 24 kilometers, covered in 18 hours. The Austrian alpinist Louis Philipp Friedmann tried to follow this tour together with a mountain guide in 1892 , and despite the good conditions it took much longer to get there, whereupon he considered Steinberger's description to be unbelievable and publicly questioned its first ascent. Steinberger stuck to his claim, however, so that the question was controversial for a long time. In 1929 Steinberger's biographer Joseph Braunstein was able to gain some new insights into Steinberger's route and prove that Steinberger had adequately described the view from the summit. Based on these facts and taking into account the better glacier conditions at the time and the higher speed caused by going it alone, Steinberger's first ascent is largely believed to be credible today.

The first fully recognized ascent of the Königspitze was achieved on August 3, 1864 by the English alpinist Francis Fox Tuckett with his companions TF and EN Buxton and the Swiss mountain guides Christian Michel and Franz Biner. Their starting point was Santa Caterina Valfurva , from where they reached the summit in just seven hours through the Forno and Cedectal valleys and via today's normal route. The group then descended to Sulden and continued the same day to Trafoi, from where, after only one rest day, they managed the first ascent of the Ortler in 30 years.

The east face was first climbed on September 17, 1864 by Josef Anton Specht , led by Franz Pöll . In 1878, Alfred von Pallavicini and Julius Meurer, two leading members of the Austrian Alpine Club, came to the Ortler region with the aim, among other things, of finding an ascent to the Königspitze from the Sulden side. On July 6th, together with Alois and Johann Pinggera and Peter Dangl , they managed the first ascent of the Langen Suldengrates (Mitschergrates) from the Schaubachhütte, the most difficult climb to date. On July 26th, 1880 Johann Grill took R. Levy and A. Jörg von Sulden to the Suldenjoch and from there over the Kurzen Suldengrat. B. Minnigerode, Alois and Johann Pinggera and Peter Reinstadler opened up the 50 ° steep north-east face in 1881 mainly with the then popular technique of stepping and were the first to venture into the area of the north face. With the east-north-east ridge in 1886, all the ridges of the Königspitze were committed; the route through the south face, which was first climbed in 1887, has not been repeated to this day. The north face, which had not yet been climbed, could hardly be climbed with the equipment at the time.

It was not until September 5, 1930 that attempts were made to climb the north face, which is up to 60 ° steep and 600 meters high. Hans Ertl , who later became the first to climb the north face of the Ortler, succeeded in the first attempt with Hans Brehm on the Ertlweg, which is named after him. Even then, Ertl was planning to use the foam roller, but this could not be done due to lack of time and material. The Aschenbrennerführe, which runs a little to the left of the Ertlführe and which Peter Aschenbrenner and H. Treichl started for the first time on September 1st, 1935 , is considered to be much more difficult and has not been repeated to this day. The Brigatti-Zangelmi north-east wall guide followed in 1937, and the Apollonio guide in 1943. Another significant increase in difficulty meant the first direct exit from the north face via the foam roller in technical climbing that still existed at the time . He succeeded on September 22, 1956 Kurt Diemberger , Hannes Unterweger and Herbert Knapp. Diemberger then named the structure after the pastry of the same name. The original foam roller was only climbed once more before it was demolished.

It was not until 1971 that Heini Holzer once again started a major alpine event with the first skiing of the Minnigerode guide in the northeast face. New routes were not opened until 1976 with Klimek / Gruhl, 1978 with Klimek / Grasegger and 1984 in the western north face. But these routes are of little importance today. In 1995 "Soldato delle Pale Rosse" was celebrated for the first time. "Ghost Zebrù" from 1997 has hardly been repeated so far. Most of the newer tours are only accessible under certain conditions and were mainly developed for the sake of the first ascent. Otherwise, the new development has practically come to a standstill due to the rock, which has become even more fragile with the thawing of the permafrost . In 2010, however, there was another first ascent when Martin and Florian Riegler opened the extreme mixed route Chess Matt (M10 + WI5 55 °) in the eastern part of the north face . In the course of this tour, Martin Riegler was also able to realize the first base jump at the Königspitze.

Mountain War

When, at the beginning of the mountain war of 1915–1918 , many high mountains in the Ortler Alps and even the Ortler itself soon became a theater of war, the Königspitze was spared the battle for a long time. Only the Königsjoch was briefly occupied by Italy in 1915.

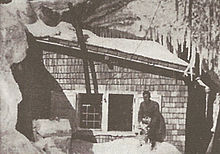

However, patrols of the Kaiserschützen and the kk Standschützen monitored the area and in the spring of 1917 recognized signs of attempts by the Alpini to occupy the Königspitze. Since the Königspitze was considered an excellent vantage point of great strategic importance, in May the route to the Königspitze over the Königsjoch was equipped with the first trenches and simple accommodations, mostly snow caves and tents, in great haste and under constant fire . The Königsjoch was subsequently expanded to a larger position with barbed wire entanglement and trenches with machine guns. At the summit of the Königspitze, a heated barrack for a crew of 16 was built into a crevasse several meters deep . Two machine guns were placed on the summit, which was secured against the Suldengrat with barbed wire. The Suldengrat was occupied by Italian armed forces shortly after the summit position was established, and they maintained a position equipped with machine guns only 150 meters from the summit.

In contrast to the Ortler position, which was hardly affected by the immediate fire, there were repeated battles here, in particular through attempts by the Italians to conquer the summit. The transport of weapons and food over the southeast ridge to the summit was dangerous and constantly threatened by fire from the Italian-occupied Pale Rosse, so that it could only be done at night. In 1918, a new ascent was created through the south-east walls, which ran through tunnels blasted into the glacial ice at the particularly dangerous places. The summit position was also expanded with a captured Ansaldo gun. The barracks in the fissure were replaced by accommodation for 25 soldiers blasted into the rock, which was largely destroyed by lightning strikes in the last days of the war. A material ropeway led from Sulden via the Schaubachhütte to the Königsjoch and a small manual winding even to the summit, there was also a telephone connection. In return, the Alpini owned a cable car from the Cima della Miniera, which supplied the position on the Suldengrat.

Towards the end of the war the construction of an ice tunnel towards Suldengrat began. He was supposed to attack the Italian position , following the example of the Hohe Schneider , but this did not happen after the end of the war. Remains of fortifications can still be seen on the Königspitze, the ice repeatedly releases the soldiers' equipment and even live ammunition.

literature

- Peter Holl: Alpine Club Guide Ortleralpen . Ed .: German Alpine Association , Austrian Alpine Association , Alpine Association South Tyrol . 9th edition. 2003, ISBN 3-7633-1313-3 , pp. 237-250 ( Google Books [accessed March 13, 2010]).

- Wolfgang Pusch: Ortler - Königspitze - Zebrù . Rother, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-7633-7027-7 .

- Hanspaul Menara : The most beautiful 3000m peaks in South Tyrol. 70 worthwhile alpine tours. Athesia, Bozen 2014, ISBN 978-88-8266-911-9

Web links

- Tour description Königspitze Ostwand (Ostrinne) on bergstieg.com

- Königspitze on summitpost.org (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Italian survey, according to Austrian survey 3859 m above sea level. A. , cf. Alpine Club Guide p. 237.

- ^ A b Peter Holl: Alpine Club Guide Ortleralpen. P. 25.

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Pusch: Ortler - Königspitze - Zebrù. P. 15.

- ^ A b Manfred Reichstein: Geology of the Ortler group . In: Wolfgang Jochberger, Südtiroler Kulturinstitut (Ed.): Ortler. The highest peak in the whole of Tyrol . Athesia, Bozen 2004, ISBN 88-8266-230-6 , p. 57 .

- ^ Peter Holl: Alpine Club Guide Ortleralpen. P. 26.

- ^ A b Manfred Reichstein, Geology of the Ortler Group , in: Wolfgang Jochberger, Südtiroler Kulturinstitut (Ed.): Ortler. The highest peak in the whole of Tyrol . Athesia, Bozen 2004, ISBN 88-8266-230-6 , p. 62 .

- ^ Peter Holl: Alpine Club Guide Ortleralpen. P. 28.

- ^ Peter Ortner : The Ortler group in the Stelvio National Park . In: Wolfgang Jochberger, Südtiroler Kulturinstitut (Ed.): Ortler. The highest peak in the whole of Tyrol . Athesia, Bozen 2004, ISBN 88-8266-230-6 , p. 50 .

- ↑ a b c Wolfgang Pusch: Ortler - Königspitze - Zebrù. P. 16.

- ↑ J. Stötter, S. Fuchs, M. Keiler, A. Zischg: Oberes Suldental. A high mountain region under the sign of climate change . In: E. Steinicke, Institute for Geography (Ed.): Geographischer Excursionsführer Europaregion Tirol, Südtirol, Trentino (= Innsbruck Geographical Studies . Volume 33 , no. 3 ). tape 3 : Special excursions in South Tyrol . Self-published, Innsbruck 2003, ISBN 3-901182-35-7 , p. 244 ( sven-fuchs.de [PDF; accessed on March 14, 2010]).

- ^ Reinhold Messner: King Ortler . Tappeiner, Lana 2004, ISBN 88-7073-349-1 , pp. 151 .

- ↑ a b Freiherr von Lemprü : The King of the German Alps and his heroes. Ortlerkampf 1915-1918 . Ed .: Helmut Golowitsch. Book Service South Tyrol, Bozen 2005, ISBN 3-923995-28-8 , p. 178–179 (first edition: 1925).

- ↑ Wolfgang Pusch: Ortler - Königspitze - Zebrù. Pp. 17-19.

- ^ Peter Holl: Alpine Club Guide Ortleralpen. Pp. 237-238, 243.

- ^ Walter Frigo: Stelvio National Park . SRL, Trento 1987, ISBN 88-7677-001-1 , p. 44 .

- ^ A b Peter Holl: Alpine Club Guide Ortleralpen. P. 32.

- ^ Peter Ortner: The Ortler group in the Stelvio National Park . In: Wolfgang Jochberger, Südtiroler Kulturinstitut (Ed.): Ortler. The highest peak in the whole of Tyrol . Athesia, Bozen 2004, ISBN 88-8266-230-6 , p. 49-50 .

- ^ Walter Frigo: Stelvio National Park. P. 96.

- ^ Walter Frigo: Stelvio National Park. P. 151.

- ^ Walter Frigo: Stelvio National Park. P. 168.

- ↑ Heinrich Erhard, Autonomous Province of Bolzano, Office for Hunting and Fishing, Forestry Department (Ed.): Das Steinwild in Südtirol . Athesia, Bozen 2000, ISBN 88-8266-073-7 , p. 18 .

- ↑ Heinrich Erhard, Autonomous Province of Bolzano, Office for Hunting and Fishing, Forestry Department (Ed.): Das Steinwild in Südtirol . Athesia, Bozen 2000, ISBN 88-8266-073-7 , p. 55 .

- ^ Franco Pedrotti: The Ortler in the Stelvio National Park . In: Reinhold Messner (ed.): König Ortler . Tappeiner, Lana 2004, ISBN 88-7073-349-1 , pp. 216 .

- ^ Peter Ortner: The Ortler group in the Stelvio National Park . In: Wolfgang Jochberger, Südtiroler Kulturinstitut (Ed.): Ortler. The highest peak in the whole of Tyrol . Athesia, Bozen 2004, ISBN 88-8266-230-6 , p. 50-51 .

- ^ A b Egon Kühebacher : The place names of South Tyrol and their history. The names of the mountain ranges, groups of peaks and individual peaks in South Tyrol . Ed .: State Monument Authority Bozen, South Tyrolean Provincial Archives. tape 3 . Athesia, Bozen 2000, ISBN 88-8266-018-4 , p. 147 .

- ↑ Julius Meurer: Illustrated Special Guide through the Ortler Alps . A. Hartleben, Vienna / Pest / Leipzig 1884.

- ^ Egon Kühebacher : The place names of South Tyrol and their history. The names of the mountain ranges, groups of peaks and individual peaks in South Tyrol . Ed .: State Monument Authority Bozen, South Tyrolean Provincial Archives. tape 3 . Athesia, Bozen 2000, ISBN 88-8266-018-4 , p. 182 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Pusch: Ortler - Königspitze - Zebrù. P. 24.

- ↑ Robert Winkler: say about the Ortler . In: Wolfgang Jochberger, Südtiroler Kulturinstitut (Ed.): Ortler. The highest peak in the whole of Tyrol . Athesia, Bozen 2004, ISBN 88-8266-230-6 , p. 215 .

- ^ Peter Holl: Alpine Club Guide Ortleralpen. P. 238.

- ^ Peter Holl: Alpine Club Guide Ortleralpen . Ed .: German Alpine Association , Austrian Alpine Association , Alpine Association South Tyrol . 9th edition. 2003, ISBN 3-7633-1313-3 , pp. 237-250 ( Google Books [accessed March 13, 2010]).

- ↑ Königspitze Ostwand (Ostrinne) ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. from bergstieg.com, accessed April 28, 2011.

- ↑ Wolfgang Pusch: Ortler - Königspitze - Zebrù. P. 35.

- ↑ Wolfgang Pusch: Ortler - Königspitze - Zebrù. Pp. 34-38.

- ^ Reinhold Messner: King Ortler . Tappeiner, Lana 2004, ISBN 88-7073-349-1 , pp. 114 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Pusch: Ortler - Königspitze - Zebrù. Pp. 38-40.

- ↑ Wolfgang Pusch: Ortler - Königspitze - Zebrù. Pp. 67-69.

- ↑ Wolfgang Pusch: Ortler - Königspitze - Zebrù. Pp. 72-73.

- ↑ Checkmate. bergstieg.com, May 1, 2010, accessed May 4, 2010 .

- ^ Heinz von Lichem: Mountain War 1915–1918. Ortler-Adamello-Lake Garda . Athesia, Bozen 1980, ISBN 88-7014-175-6 , p. 142-143 .

- ↑ Freiherr von Lemprü: The King of the German Alps and his Heroes. Ortlerkampf 1915-1918 . Ed .: Helmut Golowitsch. Book Service South Tyrol, Bozen 2005, ISBN 3-923995-28-8 , p. 224 (first edition: 1925).

- ^ Heinz von Lichem: Mountain War 1915–1918. Ortler-Adamello-Lake Garda . Athesia, Bozen 1980, ISBN 88-7014-175-6 , p. 144 .

- ↑ Lieutenant Romeiser: Europe's highest glacier front . In: Helmut Golowitsch (Ed.): The King of the German Alps and his heroes. Ortlerkampf 1915-1918 . Book Service South Tyrol, Bozen 2005, ISBN 3-923995-28-8 , p. 453 (first edition: 1925).

- ↑ Freiherr von Lemprü: The King of the German Alps and his Heroes. Ortlerkampf 1915-1918 . Ed .: Helmut Golowitsch. Book Service South Tyrol, Bozen 2005, ISBN 3-923995-28-8 , p. 225 (first edition: 1925).

- ^ Sebastian Marseiler, Udo Bernhart, Franz Josef Haller: Time in the ice. Glaciers release history. The front at the Ortler 1915–1918 . Athesia, Bozen 1996, ISBN 88-7014-912-9 , p. 22, 96 .