Roman-Persian Wars

For centuries, the Roman or Eastern Roman Empire and the New Persian Sassanid Empire represented the two dominant states in the Mediterranean and the Middle East . Although there were phases of peaceful coexistence between the two late ancient great powers, especially in the 5th century, their interstate relations were largely decisive military conflicts, which are sometimes referred to in research as Roman-Persian wars .

The military conflicts began with the formation of the Sassanid Empire in the 3rd century AD and only came to an end with the victory of the Eastern Roman emperor Herakleios in 628/30. The fighting was particularly intense during the times of Shapur I (240 / 42-270), Shapur II (309–379), Chosraus I (531-579) and Chosraus II (590–628). The attacks came from both the Roman and the Persian side. After the last and greatest Roman-Persian war (603–628), the two exhausted empires fell victim to the expansion of the Arabs . These destroyed the Sassanid Empire and conquered the Roman Orient provinces. This event is viewed by many historians as the final end of antiquity (see also Pirenne thesis ).

The starting point: Rome and Persia at the beginning of the 3rd century

The death of the emperor Marcus Aurelius in 180 AD was already considered by ancient authors as a turning point for the Roman Empire, as a number of worse emperors followed after Marcus Aurelius. The reign of the supposed "philosopher on the throne" had been but dominated already by a permanent defensive struggle at the borders: in the Danube region had Marcomannic wars raged and Rome claimed last reserves in the East who had Parthians are held down. It was only with difficulty that Marcus Aurelius succeeded in temporarily stabilizing the borders of the empire. His son Commodus , who was not very successful as emperor , was murdered in 192. After a bloody civil war ( Second Year of the Four Emperors ) founded the from Africa originated Septimius Severus the dynasty of the Severi that should govern the kingdom to 235th Nevertheless, contemporaries noticed, like Senator Cassius Dio , who came from the east of the empire , that the “golden age” ended with the death of Mark Aurel and an era of “iron and rust” began. This perspective has also strongly influenced modern research. It is correct that the pressure on the Roman Empire increased during these years, although today it is controversial whether it was primarily the threat from external enemies or whether the instability of the empire and internal turmoil in the empire was the real cause of the Problems were.

The power of the Severan emperors rested in large part on their control of the legions . The donations for the soldiers were constantly increasing, which at the same time also increased their desires. Septimius Severus had also gradually doubled the pay of the army, which at the same time massively increased the financial needs of the empire, which led to a growing tax burden. In addition, it was not possible to compensate for the loss of reputation that the empire had suffered during the civil war; the ruler's position in relation to the army and court became more precarious. So there were often enough conspiracies, for example against Caracalla , who was popular with the people and the military, but also acted unscrupulously and even had his own brother Geta killed; also against Emperor Elagabal , whose religious policy had angered many Romans. The last emperor of the Severus Imperial family, Severus Alexander , was finally murdered in 235 by enraged soldiers who doubted his military expertise. The subsequent emperors only stayed on the throne for a few years, but mostly not even more than a few months. The empire entered a time of crisis that modern research traditionally calls the Third Century Imperial Crisis . Only emperors like Aurelian and finally Diocletian were able to stabilize the empire in a sustainable manner.

Developments that had taken place in the East played a significant role in the growing problems facing Rome at the beginning of the third century. There, in AD 224, the Parthian king Artabanos IV from the Arsacid dynasty was defeated and killed in a battle by an insurgent prince named Ardaschir . Ardaschir, who made himself the new king in 226, came from a dynasty of regional princes who ruled in Persis and traced their origins back to a historically inconceivable progenitor named Sasan . In modern research, the new masters of Iran, who succeeded the Parthians under Ardashir, are therefore also referred to as Sassanids (more correctly: Sasanids ). This dynasty would rule Persia for more than 400 years and found the last pre-Islamic empire of the ancient Orient.

Ardaschir and his successors initially continued the Parthian traditions in important areas, but were under great pressure to legitimize them. The new dynasty needed visible successes. The Romans were soon to find out what that meant: only a short time after Ardashir had temporarily consolidated his internal power, war broke out with Rome. Persian armored riders, called kataphraktoi , proved to be equal opponents of the Romans. It is difficult to determine from whom the first attacks originated, but in any case Rome was soon embroiled in a costly war. Even if the various tribes on the Rhine and Danube represented a growing threat, militarily they could not be compared with the well-organized Sassanids, who soon developed into masters of siege technology.

Since the late republic , Rome had generally had the military initiative and therefore mostly decided for itself when and where to wage war. The Parthians had almost never attacked of their own accord (even the attack of 161 was probably a preventive strike that preceded a Roman offensive), but mostly behaved very defensively. This has now changed; the Sassanids apparently acted more aggressively. In recent research, however, it has been pointed out that the Romans themselves were responsible for this in particular: Septimius Severus annexed northern Mesopotamia around the year 200 and converted it into a Roman province; from the point of view of the great kings, who had always insisted on the Euphrates border , this was absolutely unacceptable. The last Arsacids already vehemently demanded the return of these areas and after the Sassanids had replaced them, they pursued this goal with great vigor, albeit ultimately unsuccessfully. Cassius Dio already recognized that the annexation of northern Mesopotamia had been a serious mistake, since the defense of the territories east of the Euphrates cost the Romans dearly.

Iran, culturally and militarily highly developed, in any case became the nemesis of Rome under the new dynasty and should remain so for the next centuries. This changed the strategic situation of the Romans fundamentally. It was not least the wars with Persia that forced the emperors to carry out far-reaching reforms in the decades after 250 in order to better use the resources of the Imperium Romanum and thus defy the Sassanid attacks. The fact that the protection of the rich Roman provinces of the Orient always had priority contributed to the fact that the west of the Mediterranean area slipped out of imperial control in the 5th century: The Teutons profited decisively from the fact that the eastern border was always secured; Over half of all Roman troops were stationed on the Persian border, and even more in the event of war. Since the annexation of northern Mesopotamia, the emperors have been permanently exposed to the danger of a two-front war - a strategic dilemma that, however, also applied in a very similar way to the Persians, who faced the (Eastern) Roman Empire in the west and the Hunnic and Turkish peoples in the northeast.

Rome soon recognized the neo-Persian Sassanid Empire as an (almost) equal power, the Persian great kings in Ctesiphon saw the Romans in a similar light, as after a few decades of fierce fighting it had become clear that neither side was strong enough, the other decisive beat. In the 5th and 6th centuries in particular, the two great powers saw each other as actually equals, the ideology and court ceremonies of the two empires increasingly converged. Admittedly, this did little to change the fact that both great powers were always keen to weaken the other as much as possible, whereby economic interests also played a role. It was the beginning of a centuries-long struggle: only with the end of late antiquity and the fall of the Sassanid Empire did the Roman-Persian dualism come to an end.

In the following, both the corresponding military operations are to be described in outline and an overview of the initial political situation of the respective conflicts and their results are given. In this context, the respective political conditions in Persia and Rome will also be discussed in smaller digressions.

Ardashir I - the beginning of the military conflict

After Ardaschir I had put down his internal opponents around 230, he began to expand his domain, which should bring him into conflict with Rome. A first advance was directed against Armenia . The country, due to its geographic location and resources, had been a constant point of contention between Rome and the Parthian Empire. The Sassanid Empire should also have a fundamental interest in Armenia in the future, especially since members of the old Parthian royal house of the Arsacids , who saw the Sassanids as usurpers, were to rule there up to 428 .

However, the Persian approach in the west was defensive in that, as I said, they only wanted to regain the Euphrates line in order to secure the border against Rome: the Romans had only annexed parts of northern Mesopotamia 30 years earlier, and Ardashir obviously wanted to reverse this. However, his offensive in Armenia did not have the hoped-for success, nor did an attack on the Kingdom of Hatra in Mesopotamia , an ally of Rome and the Arsacids. The Roman emperor Severus Alexander meanwhile prepared for war and began a counter-offensive against the Persian capital Seleukia-Ctesiphon in 232 , which, however, literally fizzled out. One of the three Roman army pillars was defeated by the Persians, the other two withdrew after minor successes with some heavy losses. The following battles, which took place mainly in Mesopotamia, did not bring a decision either, so that Severus Alexander soon broke off the operations in order to be able to turn to the Teutons on the Rhine. After the emperor's death in 235 and the ensuing turmoil, Ardashir launched another offensive. This time the great king was more successful: In 235/36 the strategically important cities of Karrhai and Nisibis fell into Persian hands, 240 (after more than two years of siege) also the hard-fought Hatra.

The motives of Ardashir for the crackdown on Rome have often been discussed in scholarship. Western sources assume that the great king wanted to renew the old Achaemenid Empire , whereby it should be noted that the western sources were usually hostile to the Sassanids anyway. Ardashir's self-testimony in this regard is not available, especially since he only referred to himself as "King of the kings of Eran [Iran]" and thus by no means expressed an exaggerated imperial self-image. Ardaschir was more likely to have tried to prove himself in battle, to prove his suitability as the new king and thereby legitimize his de facto usurpation. Ultimately, however, much remains a question of the interpretation of the existing sources.

The Hatras case sparked a new determination in Rome to take action against the Persians. But in 242 Ardashir died. His son and successor Shapur , who had been in charge of government since 240, should continue the struggle.

Shapur I - Triumph over three emperors

Shapur I is generally regarded as one of the most important Sassanid kings, whose memory in Iran has not yet completely died out. Internally, he pursued a fairly tolerant religious policy and improved the administration of the Reich, which may now have been more centralized.

Shapur was initially no less successful militarily. He led a total of three campaigns against Rome, the exact chronology of which, however, caused some difficulties for modern research due to the problematic sources (probably 243/44, 252/53 to 256/57 and finally 260). Occasionally the Western (Greco-Roman) sources contradict the Sassanid self-testimony, although they are not particularly abundant. An important source is the famous trilingual inscription (in Middle Persian, Parthian and Greek) from Naqsch-e Rostam , the so-called res gestae divi Saporis , a report by Shapur about his victories. Even if one has to exercise a certain degree of caution when using the crime report, its value is assessed as quite high by modern research. The situation is different with Western sources, such as the highly unreliable Historia Augusta . They often offer hardly any reliable details about the course of the battles, although the Greek historical works (such as the comparison of the fragment of Philostratos of Athens with the res gestae divi Saporis shows) tend to contain more and better material than the brief notes in the few Latin works .

The first campaign of Schapur fell in the period from 242 to 244. After the life of the three Gordians in the Historia Augusta , Emperor Gordian III broke . from Antioch on the Orontes , one of the most important cities of the empire, to the east to oppose Shapur. The Roman attack had been thoroughly prepared, and when the war began, the gates of the Temple of Janus were opened in Rome. At Rhesaina (today's Ras al-Ain near Nisibis) the Romans actually defeated the Persian king in a great battle in 243. They are said to have regained control of the lost territories in Mesopotamia. Shortly thereafter, however, the emperor's Praetorian prefect , Philip Arabs , allegedly intrigued against Gordian and then had him murdered - at least that's what later Western sources claim.

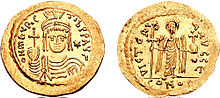

A completely different picture emerges from the report of Schapur's deeds, however: According to this, Gordian, who marched against Ctesiphon after his victory at Rhesaina (which Shapur kept silent), was defeated at the beginning of 244 in the battle of Mesiche (about 40 kilometers west of today's Baghdad ) beaten and killed; then Philip was proclaimed emperor. Even later Byzantine sources (such as Johannes Zonaras , who could fall back on older material) do not indicate that Gordian was murdered; it is possible that he succumbed to his injuries sustained in the Battle of Mesiche. In any case, after the death of Gordian, Philip Arab was forced to sign a treaty with Shapur. He celebrated the peace treaty on the reverse of a coin with the inscription PAX FVNDATA CVM PERSIS. Obviously the Roman victory at Rhesaina had not been decisive, even if the Persians were temporarily pushed back. Overall, Schapur's version seems more plausible. This treaty, on which only a few sources go into, was quite favorable for the Sassanids: It provided for payments from Rome to Persia and possibly territorial concessions in Mesopotamia; but at least Rome withdrew its support from Armenia.

The fact that Philip was nevertheless given victory names like Persicus and (now anachronistic) Parthicus maximus should not hide the fact that the Romans had suffered a severe defeat. Shapur had his victory immortalized on numerous rock reliefs and resumed fighting against Rome in 252 or 253. The course of this second expedition (the so-called second agoge ), which lasted until 256/57, can again be reconstructed primarily on the basis of Schapur's report. Apparently the new Roman emperor Decius had less interest in a policy of reconciliation with Persia and had therefore opposed Persian ambitions with regard to Armenia. Schapur saw this as a reason for war. First he conquered Armenia and then, taking advantage of the turmoil after the death of Emperor Decius, invaded Syria and Mesopotamia. Probably in the spring of 253 Shapur marched with his army along the Euphrates to Roman territory, bypassing the strong Roman fortresses Circesium and Dura Europos . The Sassanids suffered a minor defeat at Emesa (significantly not by a Roman army detachment, but by local forces under Uranius Antoninus ), but this was only a minor setback, because Shapur's troops, the core of which was armored fighting, destroyed a Roman army of allegedly 60,000 men (the number should be clearly exaggerated) near Barbalissos on the Euphrates. Hierapolis , north of Barbalissos, and above all Antioch on the Orontes were then conquered by the Sassanids (briefly). The Persians even penetrated as far as Cappadocia and were able to storm the heavily fortified Dura Europos, but Schapur soon withdrew.

The situation in Rome's eastern provinces was so serious that Emperor Valerian , who had come to power in 253, felt compelled to go to the east personally. Valerian gathered a large army there and took to the field against Shapur. In the early summer of 260 there was a battle near Edessa , in which Valerian's army was defeated. That alone would have been bad enough if the emperor had not also fallen into Persian hands in the course of the battle. The capture of Valerian - a unique and, for the Romans, extremely disgraceful event - was recorded by Shapur in his report of the facts as well as on rock reliefs (as in Bischapur ):

- In the third campaign, when we advanced against Karrhai and Edessa and besieged Karrhai and Edessa, Emperor Valerian marched against us, and with him there was an army of 70,000 men. And on the other side of Karrhai and Edessa, a great battle for Us took place with Emperor Valerian, and We captured Emperor Valerian with our own hands and the rest of them, the Praetorian prefects and senators and officers, all whoever were leaders of that army, all of them We took these with our hands and deported them to Persis.

Some of the Western sources report that the emperor's capture was the result of betrayal on the part of the Persians who overcame Valerian during ongoing negotiations, but other authors tend to confirm the account of Shapur. Valerian ended his life in Persian captivity, as did the surviving Romans, who were abducted from Shapur to the Sassanid Empire, where they were settled in a city newly founded by the great king. After the battle, Shapur took several cities, but above all Antioch was sacked a second time.

The weakness of the empire at that time also played a role in the fact that Gaul and other areas in the west broke away from the central Roman authority and the borders on the Rhine and Danube were as oppressed as the eastern border. Only Emperor Aurelian was able to stabilize the empire again. Shapur, on the other hand, who proudly called himself “King of Iran and non-Iran” , had proven that the Sassanid Empire was an equal opponent for Rome. However, he had made an unwise decision in retrospect when he rejected an alliance offer from the king of the oasis city of Palmyra , Septimius Odaenathus ; Odaenathus then contacted the Romans, who were grateful for any help. Since Rome was unable to offer effective resistance to the Persians, the defense of the Roman Orient provinces now fell to Odaenathus of Palmyra, who successfully fulfilled this task and was able to defeat the Persian troops on their return march (end of 260). Soon afterwards, Palmyrene and Roman troops counterattacked. Several historians seem to have reported on these struggles, but nothing of their works has in fact survived; these include Nikostratos of Trebizond and Philostratos of Athens .

In the end, Shapur could hardly exploit his victories. The fact that the king acted more defensively in the west in the years after 260 (Palmyrenian troops even penetrated as far as Ctesiphon in 262) may also have something to do with Shapur's operations on the eastern border of Persia, where the Kushan made themselves felt and the Shapur had some problems should prepare. Nevertheless, it can be said that the Sassanid territorial gains in the west were minimal and that the fighting also resulted in high blood tolls on the Persian side. The successes against Rome had legitimized the new dynasty, but despite the great victories between 244 and 260, the Persians could not achieve their likely war goal, access to the Mediterranean - while the Romans were to succeed gradually in the years after 260, through far-reaching internal ones Reforms to adapt economic efficiency and military clout to the new foreign policy situation.

Diocletian's Persian War

Until the death of Schapur (270 or 272) and after that, the Roman-Persian border was initially quiet. On the one hand, this was due to the turmoil in the Roman Empire, which could only be largely overcome under Emperor Aurelian . On the other hand, the Sassanid kings also had enough to struggle with internal problems, such as the rise of Manichaeism , which Bahram I and Bahram II vigorously opposed. When Bahram II was also busy fighting a rebellion in the east of his empire, the Romans under Emperor Carus seized the opportunity and invaded Mesopotamia in 283. They reached the capital Ctesiphon, which could even be taken, but Carus died there, so this idea remained an episode.

Under Emperor Diocletian , who came to power in 284, the "period of crisis" of the Roman Empire ended, which was profoundly reformed and strengthened in the period that followed by Diocletian and the co-emperors he appointed (see Roman Tetrarchy ). That was how late antiquity began . Diocletian intended to ensure peace on the Roman eastern border as well. There were negotiations with Bahram II in 287, which ended with a guarantee of peace for the border. But this solution was only to be temporary, because as soon as Diocletian had ensured peace inside the empire - in addition to securing the border against the Teutons, local uprisings also had to be put down - he turned back to the Persians. The expelled Armenian King Trdat III. he reinstated him in his kingdom in 290, but this also affected Sassanid interests. Narseh , Persian king since 293, finally reacted to the Roman action and, probably also following the example of his father Shapur I, intervened in Armenia in 296. An important motive was probably to assert itself against the strengthening Roman Empire after the Sassanid Empire had gone through a phase of weakness in the 270s and 280s, combined with a ten-year civil war ( Bahram II had to assert himself against his brother Hormizd in the east). Diocletian, who was busy putting down an uprising in Egypt , had entrusted his Caesar (lower emperor) Galerius with the task of repelling the Persian attack. However, between Kallinikos and Karrhai in Mesopotamia, Galerius suffered a heavy defeat in 297 (the exact chronology of events is disputed).

Diocletian hurried from Egypt to Syria and was allegedly so angry at the defeat of his Caesar that he let Galerius, clad in a purple cloak, run a mile in front of his chariot. In 298 (or maybe 297) the Romans went on the offensive again. Galerius advanced into Armenia, where the terrain did not allow an effective development of the dreaded Persian armored fighting, while Diocletian led troops to Mesopotamia. At the Armenian Satala , Narseh was decisively defeated by Galerius in a surprise attack. Even Narseh's harem fell into the hands of the Romans, so that the great king, worried about his relatives, had to plead for peace. In the so-called Peace of Nisibis in the year 298 (some research also advocates the year 299), the Sassanids lost five provinces east of the Tigris as well as northern Mesopotamia with the strategically and economically important Nisibis , which was also determined as the only place on which trade between the two great powers could be carried out in the future.

Diocletian's victory meant a tremendous increase in prestige for Rome. Some of the treaty provisions, such as the surrender of Nisibis and above all the expansion of Roman influence to the left bank of the Tigris, were apparently perceived by the Persians as humiliation, while the Roman side regarded it as the price for the victory they had won. From the Persian side, Galerius was told that Persia and Rome were the two great powers of the world and that it was not necessary to work towards the annihilation of the other. The Romans should therefore not challenge luck. Galerius became furious about this and recalled the death of Emperor Valerian in captivity (see above). Ultimately, the treaty was not intended to help eliminate the existing tensions between the two great powers; it could only cover them up. Some historians nevertheless rate the Roman peace conditions as moderate, since Galerius could in principle have asked for more, but this assessment probably overlooks how humiliating the treaty must be seen by the Persian side. The outbreak of new fighting was therefore only a matter of time.

Rome and Persia in the time of Constantine the Great: the consequences of the Constantinian turning point

Diocletian was the only Roman emperor to abdicate voluntarily in 305. The tetrarchy system of government that he had devised, which provided for two senior ( Augusti ) and two junior emperors ( Caesares ), collapsed during his lifetime. In 306 Constantine , son of the recently deceased Augustus Constantius I , was proclaimed emperor by the troops in Britain , contrary to the provisions of the tetrarchical order. Until 312 he controlled the entire western part of the Roman Empire and now made a religious-political decision of world-historical importance: the privilege of Christianity , which had been persecuted only a few years earlier . By 324 Constantine had defeated his last rival and was now the sole ruler of the Roman Empire.

The so-called Constantinian turn , i.e. the favoring of Christianity, also had an impact on the relationship between Rome and Persia. There, in 309, Shapur II had been made king as an infant. Initially, Persia was therefore in a crisis. In the middle of the 30s of the 4th century, however, Schapur was finally able to run the business of government independently and soon afterwards prove to be an important ruler. The developments in the Roman Empire had to worry the great king, because many of his subjects, especially in Mesopotamia, were Christians. As long as the Christians in the Roman Empire had been persecuted, the great king could be largely certain of their loyalty. But now he feared a collaboration between the Christians in his empire and the Roman emperor, who now saw himself as the protector of Christianity and sacredly cemented his empire with Christian ideas. Constantine had also expressed his new self-image in a letter to Shapur.

Now that Armenia and Iberia were also under Christian influence, Shapur felt threatened, probably not entirely without good reason. He rallied troops in Mesopotamia to forcibly revise the provisions of the Nisibis Peace Treaty and invaded Armenia, where he put a puppet king on the throne. Constantine then sent his son Constantius to Antioch and his nephew Hannibalianus to Asia Minor. Embassies were exchanged over the year 336; there was no success in mediation, so that Constantine prepared for the Persian War.

Constantine's plans for victory are not entirely clear. Hannibalianus, as rex regum et Ponticarum gentium, was supposed to become the client king of Armenia; perhaps Constantine also intended to conquer the entire Persian Empire and make it a Roman client state as well. Regardless of what plans Constantine had (not to mention how realistic they were), his death on May 22, 337 made all considerations redundant as the planned Persian War did not take place. After the Purge of 337, Constantine's sons were to be embroiled in a bloody power struggle that would last for years. At the end of it, Constantius was to rule the entire empire from 353 onwards. Throughout his entire reign he had to deal primarily with one opponent: Shapur II, who continued the fighting after the death of Constantine and was supposed to keep Rome in suspense for decades , the reason given by Ammianus Marcellinus , the so-called " lies of Metrodorus ", however is not believable.

War between "brothers": Constantius II and Shapur II.

Shapur II took advantage of the turmoil in the Roman Empire after the death of Constantine and invaded Roman Mesopotamia. His goal was to regain Nisibis , but the first siege failed in 337 (or 338). Two more sieges were to follow in 346 and 350, without the Persians succeeding in conquering the city. At the same time, the great king intervened in Armenia. A domestic political measure was the beginning of a persecution of Christians in Persia, which was motivated for political, but not for religious reasons. In 338 Constantius II , now emperor in the east of the Roman Empire, took action against Shapur. Especially on the occasion of the new Persian War, an anonymous author wrote the Itinerarium Alexandri , the beginning of which has been preserved and which calls on the emperor to imitate Alexander the great and conquer Persia.

Apparently Constantius tried to avoid open field battles. Rather, his plan was that Shapur's attacks should break out on the fortress ring that protected Rome's oriental provinces. The Roman fortress system was based on holding strategically important cities that supplied the surrounding fortresses. Nisibis played a key role in this system, which explains Schapur's repeated (unsuccessful) attempts to conquer the city. At least once, however, the Romans also advanced into Persian territory.

In 344 there was a field battle near Singara . For Constantius, who used the Persian-style armored riding, victory seemed to be within reach when his soldiers stormed forward undisciplined and were defeated. However, a Persian prince was also killed in the battle. This experience may only have strengthened the emperor's defensive approach. It should also be noted that Constantius only ever had part of the total Roman army; the rest was claimed by his two brothers - or since the death of Constantine II. 340 only by Constans - in the west and was thus withheld from him. But Schapur also had to struggle with problems: In the east of his empire barbarians broke into the steppe of Central Asia, the Chionites (the forerunners of the so-called Iranian Huns ). Their invasion resulted in a truce of several years, which Constantius took advantage of to secure rule over the entire empire until 353 after the death of his brothers.

In 358 there were negotiations between Constantius and Shapur. We are very well informed about their content by the historian Ammianus Marcellinus . Ammianus, who took part as an officer in the following battles, wrote his Res gestae towards the end of the 4th century , the last great Latin historical work of antiquity. It contains a detailed and reliable description of Constantius' last Persian War, as well as a remarkable account of the negotiations:

- I, King of kings, Sapor [Shapur], companion of the stars, brother of the sun and moon, offer all the best to Caesar Constantius, my brother.

- Answer of the Roman emperor: I, victor at sea and on land, Constantius, always the exalted Augustus, offer my brother, King Sapor, all the best.

In the letter, Shapur called on the emperor to renounce large parts of Mesopotamia and Armenia, where the pro-Roman party had again prevailed. Understandably, Constantius did not even consider giving up Roman territory voluntarily. In the end, this meant that the fight would start again. But the traditional addresses also make one thing clear: Although Rome and Persia fought bitterly against each other, the mutual thinking was determined by a fundamental equivalence. You were an opponent, but still respected the other.

Admittedly, this did not prevent Shapur from reopening the fighting, which he was encouraged to do by a Roman defector named Antoninus. Shapur, in whose wake Chionite auxiliaries now appear under the leadership of their King Grumbates , had learned one thing from the past battles: a direct attack on the fortresses in Roman Mesopotamia would have little chance of success. So he bypassed them with his army (allegedly 100,000 men) and surprisingly advanced against Amida . He had to take this fortress, which the Romans had recently massively expanded, because there were at least seven legions with auxiliary troops (which corresponded to at least 7,000 men), which otherwise could cause him considerable problems. However, the siege of Amida turned out to be more difficult than expected; the fortress fell only after 73 days, in the course of which Shapur also suffered heavy losses. One consequence of the loss of the fortress Amida was the recall of the Roman general Ursicinus , who had not operated independently at the beginning of the Persian invasion but under the command of Sabinianus . In the following year, Shapur also took the strategically important cities of Singara and Bezabde. Further advances were unsuccessful, however, so that Schapur, perhaps influenced by an unfavorable oracle, withdrew 360.

Constantius could breathe a sigh of relief, but also saw that the threat was not over yet. So he requested additional troops from Gaul from his relative Julian , who had been Caesar there since 355 . When the orders in question were received, however, the Gallic troops refused to obey the order, fearing that they would be senselessly sacrificed in the Persian War: six of the seven legions destroyed in Amida had only recently been relocated from Gaul to Mesopotamia. So the soldiers elevated Julian to the new Augustus in 360 , whereby the suspicion is not unfounded that the rise was staged by Julian, who anyway did not have a good relationship with his cousin Constantius. Julian was now preparing for civil war (possibly Schapur also wanted to wait for the civil war that was looming in the empire and had therefore withdrawn), which the empire was spared by the death of Constantius II on November 3, 361 in Cilicia .

Julian's Persian War: An adventure ends in catastrophe

Julian succeeded Constantius. He wanted to undertake a Persian campaign and thus eliminate any danger posed by the Sassanids. For this purpose, the emperor traveled to Antioch on the Orontes in the summer of 362 to prepare the campaign there. In contrast to Constantius, all of the empire's troops were at his disposal.

The reasons for Julian to go to the Persian War have been discussed again and again in research, although some researchers generally doubt that Julian had a clear plan. In any case, there was no real need for such an offensive: the Persians even wanted to enter into negotiations with Julian, but Julian refused. An often-cited argument is the Alexander imitation intended by Julian , i.e. the imitation of the great Alexander . Ammianus actually reports on such a motive, especially since Alexander was an inescapable role model for every general who set out against Persia. In addition, Julian was originally a usurper , whose rule was therefore afflicted with a certain lack of legitimation; if he wanted to gain support for his extensive reform program, a great victory over the Persians - regardless of the question of the Alexander imitation - was the best route to military prestige. If he had succeeded in installing rulers by the grace of Rome in Armenia and Persia (see below), he would have been able to stand in line with emperors like Trajan and Diocletian and thus have been able to confidently face domestic political resistance.

Another realpolitical motive comes into question for Julian, namely to ensure the cohesion of the army. This was by no means guaranteed, after all, the soldiers of the Gallic field army had almost faced the troops from the east in civil war. Several of the leading officers of the Gallic army, like the emperor, were pagans, such as Dagalaifus or Nevitta , while the majority of the officers from the East were already Christians. One can also speculate about the extent to which the officers of the Eastern Army, who after all had extensive experience in fighting the Persians, were skeptical about offensive warfare. In any case, Julian's enthusiasm for war was not shared by all of his soldiers. This is evidenced by the executions of officers and the decimation of entire troops that became necessary during the later course of the campaign.

Julian set out from Antioch on March 5, 363, to the east. There are various sources of information about the strength of the army. In any case, it was one of the greatest Roman military campaigns of late antiquity (see below for details). The emperor had instructed the king of Armenia to provide him with supplies and auxiliary troops. In Hierapolis, Julian also made contact with the Arabs . Then he marched south along the Euphrates River. He was also accompanied by Hormisdas, a member of the Persian royal family who had fled to Rome years ago and served as Julian's advisor. According to some scholars, the prince was envisaged by the grace of Rome in the event of victory as the new Persian king.

The Ammianus Marcellinus report (Book 23-25) provides a detailed and reliable account of the course of the campaign . Ammianus reports of premonitions that are said to have plagued the emperor when he stopped in Karrhai. Julian decided to take a part of his army (after Zosimos , who wrote about 500 a pagan colored history of Rome, was the troop strength at 18,000 men, but perhaps it was more) under the leadership of his relative Procopius and comes Sebastianusstraße the Armenian king Arsaces to Sending support and operating in northern Mesopotamia while he wanted to march on Ctesiphon with the main force of about 65,000. In the further course of the campaign, Julian captured several enemy cities and fortresses. However, the emperor had to worry that there was still no trace of the Persian field army to be seen. The Persians limited themselves to not letting the Roman army come to rest with raids and to denying the Romans access to larger stores.

At the end of May 363 the Roman army finally reached the Persian capital Ctesiphon on the Tigris. It soon became clear to the officers that an attack on the fortified city had no prospect of success, especially since Shapur would arrive with the main Persian army at some point. Julian now made a momentous decision: Since the Romans lacked the necessary siege equipment to take Ctesiphon in the foreseeable future, and on the other hand it was not possible to return home on the original route - now it was avenged that the Romans looted on the way there and the Persians had pursued a scorched earth policy - he wanted to move into the interior in order to unite with the Roman army in northern Mesopotamia. If Shapur were to pursue them, he could still destroy him and would not run the risk of being encircled between the Persian army and the fortress of Ctesiphon. The Roman officers were not convinced of the plan, but the emperor had the last word, so the camp was broken up at the beginning of June and headed inland. The accompanying fleet was also burned, which in retrospect turned out to be a serious mistake for Julian, because now it was no longer possible to think about a river crossing. Ammianus vividly describes the hardships of retreat, which was made more difficult by the high temperatures, mosquitoes and the inadequate supply situation. The mood in the army had reached a low point.

On the march back, the main Persian army, which had meanwhile assembled, appeared. The Romans were still able to hold their own in the Battle of Maranga , but Julian died on June 26th from a wound sustained in the battle. Thereupon, after lengthy debates, a college of officers elected Jovian as the new emperor. Time was of the essence as the supply situation deteriorated as the Persians intensified their attacks. The Roman army threatened to be completely wiped out. Then Shapur II suddenly made himself comfortable to negotiate; evidently he wanted to take advantage of the favorable situation. Now he succeeded in negotiating what he had failed in the war: in the peace of 363 the Romans were forced to cede Nisibis , Singara , the areas beyond the Tigris and 15 fortresses to Persia. Diocletian's acquisitions (see above) went back to Persia, and Shapur saw himself at the goal. For the Romans, however, the treaty represented a shameful peace. Above all, they lost an important pillar of their defense system with Nisibis. The border was essentially back where it had been before 298. The official abandonment of imperial territory was a rare exception - mostly it was done de facto , but not de iure . However, it should become apparent in the period that followed that both sides could basically live with the borderline.

Julian's Persian War had ended in disaster. The emperor had obviously completely wrongly assessed the climatic and geographical conditions in the Persian Empire and, in addition, had allowed himself to be carried away by some unwise decisions. Persia was not Gaul, where Julian had celebrated his military successes, and the Sassanid armored riders were a very different opponent than the Alemanni . Although relations between Rome and Persia relaxed somewhat in the years that followed and a phase of peaceful coexistence came, the Romans should never forget the peace of 363. In all subsequent fighting, the recapture of Nisibis was therefore initially the highest priority.

Interrupted Peace: the 5th Century Wars

During the reign of Julian's successor Valens , fighting broke out in Armenia from 369/70, where Shapur II tried to enforce Persian suzerainty. A Roman army invaded Armenia and reinstated the old king Pap. In the following years, the intensity of the fighting subsided. On the one hand, this was due to the fact that Valens also had to fight against the Goths (against whom he fell in 378, see also Migration ), on the other hand, Shapur died in 379. His immediate successors only ruled for a short time. Around 400 there was a rare unity between Rome and Persia. The main reason for this was that the "Armenian problem" had been temporarily resolved. During the reign of Emperor Theodosius I (probably 387) an agreement was reached according to which Persia received most of Armenia (so-called Persarmenia ), while Rome contented itself with around a fifth of the country. The treaty brought about a border adjustment, which was also advantageous for Rome, since precisely that part of Armenia, which was important for the Roman defense, fell to the emperor. For a good 200 years (until 591), the demarcation in this region therefore remained essentially unchanged.

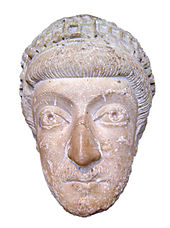

Since territorial arrangements had been made in Mesopotamia and Armenia in 363 and 387, with which both sides were basically satisfied, from around 400 onwards the Roman-Sassanid relationship eased. The mutual relations now seem to have been so good that the Roman historian Prokopios of Caesarea handed down an anecdote in the 6th century according to which the Eastern Roman Emperor Arcadius supposedly placed his little son Theodosius II on his deathbed in 408, protecting the Persian Great King Yazdegerd I. had entrusted. The church historian Socrates , who is a not unimportant source for the 5th century, described Yazdegerd as a tolerant monarch who was friendly towards Christians. Yazdegerd's tolerant religious policy also played a major role in the good relations between the two great powers; at the same time in Constantinople until 414 the Praetorian prefect Anthemius determined the policy, who endeavored to establish good relations with Persia.

Nevertheless, at the latest in 420/21 a new war broke out between Eastern and Persia, after there had been first fighting around 416. The main reason was the persecution of Christians in the Persian Empire: the Christians there, probably due to a misjudgment of the tolerant politics of Yazdgerd, began a rather extensive missionary work that was a thorn in the side of the Zoroastrian priests. In the end it got to the point that even a Zoroastrian fire temple was destroyed by Christians and the responsible bishop refused to rebuild it, whereupon Yazdegerd I had to intervene. In the last months of his life he took action against the Christians across the empire; if the king's aim should have been to emancipate himself from the Zoroastrian magicians by promoting Christianity, the arrogance and intolerance of the Persian Christians had thwarted this project. Several of these, however, fled to Roman territory, where Emperor Theodosius II granted them protection. The Augusta Aelia Pulcheria , the powerful sister of the emperor, may have spread a kind of “crusade mood” at court, and for the first time in more than 30 years there were fighting between the imperial and Sassanid troops. Yazdegerd died in late 420 or early 421; in the ensuing battle for the throne, his son Bahram V finally prevailed and continued the war against Ostrom. Due to the poor sources, details can hardly be reconstructed. Bahram, one of the most colorful personalities on the Sassanid throne, led the Persian army personally against the Roman fortress Theodosiopolis in Armenia, but his attack failed. On the other hand, with the help of his Arab allies, the Lachmids , he was able to lift the Roman siege of Nisibis before the Arabs suffered a heavy defeat in their advance on Antioch on the Orontes . The Romans, who were reinforced with fresh troops, were also able to assert themselves in the following years, the Roman magister militum (army master) Areobindus allegedly even killed a Persian general in a duel, and the Romans also defeated the Sassanid elite troops in a major battle at an unknown location the "immortals". Overall, however, the fights were unsuccessful because the balance of power was too balanced. As early as 422, therefore, a peace treaty was signed in which both sides undertook to allow Christians and Zoroastrians to exercise their faith freely. In addition, the Romans were to pay the Persians aid money to secure the Caucasus passes against the Huns , who viewed both sides as enemies. In fact, this resulted in the Romans paying tribute to the Persians (the sums paid, however, were rather insignificant). The imperial propaganda made every effort to avoid this impression.

In 441 Bahram's son and successor Yazdegerd II broke the treaty, probably due to the lack of the imperial annual money, and invaded Roman territory. Yazdegerd probably aspired to increase his prestige as a newly crowned king through a military success against the Romans; the situation was favorable as Theodosius II had just sent troops against the Vandals to support Westrom . This operation was canceled due to the Persian attack. The emperor sent his magister militum Anatolius to the great king, who was able to end the fighting after just a few weeks, as the Romans were willing to pay large amounts of money, so that they soon found their way back to the status quo, especially since Yazdegerd II was now facing the threat of the Hephthalites exposed on its northeastern border. However, it was probably also stipulated in the peace treaty that both sides were not allowed to build fortresses on the common border. Both wars remained rather episodes in the otherwise surprisingly peaceful relations between Rome and Persia in the 5th century. When the Sassanids put down an uprising by Christian Armenians around 450, Emperor Markian sent an envoy expressly to assure them that the Romans would not interfere in the conflict. Around 467, disputes in the Caucasus led to a crisis and troops from both sides were sent, but the conflict was settled diplomatically. The Romans supported King Peroz I financially in his battles against the Hephthalites around 480 (although perhaps not entirely voluntarily). Overall, the two great powers benefited from the largely peaceful relationship with one another, which enabled them to address the grave threats to which both were exposed on other fronts during the fifth century. The 6th and early 7th centuries, on the other hand, were to be characterized by an almost permanent state of war, with the conflict eventually leading both powers to the brink of collapse.

The 6th century

The Wars of Kavadh I.

The long period of peace in the 5th century came to an end in 502 when the Persian great king Kavadh I advanced into Roman territory. The main reason for the warlike action of Kavadh was probably the tense domestic political situation in Persia. There Kavadh had to fight against considerable resistance and could only maintain his throne with the help of the Hephthalites , especially since the social revolutionary sect of the Mazdakites caused some problems. According to the Chronicle of Joshua Stylites , which reports in detail about the war, Kavadh had demanded money from the Eastern Roman Emperor Anastasius , which the Emperor was not willing to pay. Kavadh assembled a large army, believed by the Romans to suppress unrest in Persarmia , surprisingly attacked in the fall of 502, captured Theodosiopolis in the Roman part of Armenia, and began the siege of Amida , which in January 503 for the second time after 359 in Persian hand fell and was provided with a Sassanid garrison.

Emperor Anastasius, who initially wanted to negotiate, sent in 503 an army of 52,000 men against the Persians, which was enormous by late Roman standards. Since the Eastern Roman troops lacked a unified leadership, they acted unsuccessfully: An army of only 12,000 men was defeated in Mesopotamia, while a second army of 40,000 men was repulsed at Amida. The defeat was blamed in particular on Flavius Hypatius , a nephew of the emperor. The Roman Edessa was then besieged by Kavadh without success. After the setbacks, Anastasius appointed a new commander in chief for the eastern border. It was the Illyrian Celer, the magister officiorum . He and his troops invaded the Arzanene region and operated there successfully, while another Roman army devastated Persarmenia. Celer and his troops seem to have finally reached the area around Ctesiphon , where he crossed the Euphrates on the Iron Bridge and plundered the country. In 505 Amida could be bought back, whose Persian garrison had withstood the Roman siege for two years. Kavadh, who had to fight the Hephthalites in the east , concluded an armistice with the emperor in 506, which was limited to 7 years, but was to last for a good 20 years. For the Romans, the operations in Mesopotamia had been a lesson that the Persians had an advantage there with the possession of the strong fortress of Nisibis. The emperor had a similarly strong bulwark built with Dara-Anastasiopolis , which the Persians hardly liked (the Romans thereby violated the treaty of 422 or 441) and was a reason for the war that broke out in 526. Whether Anastasius bought the peace with tributes to the Sassanids is likely, but in view of the sources, it is uncertain.

The second war of Kavadh against Ostrom, which broke out in 526, arose primarily from the claims to power of the two great powers in the Caucasus region. There, the small kingdom of Lazika of Constantinople, where Justin I ruled in the meantime , was courted, which affected the Persian sphere of interest, especially since the Romans saw themselves as patrons of the Christians in Persian Iberia . The Lazenkönig Tzath traveled to Constantinople in 521/22, was baptized there and married to a Christian, which the Persians rightly interpreted as a sign of a bond with Constantinople. When the Persians then tried to convert the Christian Iberians to Zoroastrianism, the Iberian king Gurgenes asked Emperor Justin for help, and a war broke out, which concentrated mainly on the Caucasus region and the Mesopotamian border area; the war continued even after Justin's death in 527. Kavadh now repeatedly demanded not only Iberia, but also the destruction of the Dara fortress and annual Roman payments of 500 gold pounds.

Justin's successor, his nephew and confidante Justinian , is considered one of the most important rulers of late antiquity . It should help Ostrom to shine again, even if the long wars on many fronts ultimately cost the empire a lot of strength. We have an excellent source for Justinian's “Persian Wars” in the histories (or war stories) of the historian Prokopios of Caesarea ; Agathias joined him . Justinian's generals Sittas and Belisarius operated quite successfully at first. Belisarius, for example, won a sovereign victory at Dara in Mesopotamia in 530 , but lost to Callinicum the following year and was therefore recalled by the emperor. Sittas was appointed magister militum of Armenia - a new post that illustrates the increased importance of this area - where he acted skillfully. In addition, Justinian was able to further consolidate the alliance with the Ghassanids founded under Anastasius . However, neither side managed to gain the upper hand.

In 531 Kavadh died, who in the same year, as in 529, had mobilized his Arab allies against the Romans. Kavadh was succeeded by his favorite son Chosrau (also called Chosroes or Husrav).

In 532, the new King Chosrau I concluded the so-called Eternal Peace with Justinian, which was linked to the high (but one-off) Roman payment of 11,000 gold pounds , and he was the seat of the Roman magister militum per Orientem , who was responsible for the defense of the eastern border Dara (which was not given up, but from now on was the location of the dux Mesopotamiae ) should move to Constantia. The fortresses conquered in the previous battles were exchanged again. Justinian used the peace in the Orient and became involved in the West, where Belisarius destroyed the Vandal Empire in North Africa and invaded Ostrogoth Italy in the following years . How deceptive the peace on the eastern border was in reality became apparent in 540 when Chosrau broke the peace treaty and invaded Syria with a large army.

Khosrau I. Anuschirvan - Ostrom on the defensive

Chosrau I was probably the most important ruler on the throne of Ctesiphon. He was to develop into Justinian's great opponent and was a monarch who was just as interested in philosophy and art as a sometimes unscrupulous general. In many ways he led the Sassanid Empire to its height. The great king had Greek and Indian works translated into (Middle) Persian. Even respected by enemies, he earned the nickname Anuschirvan ("with the immortal soul"). He also put down the Mazdakite movement and carried out military and domestic reforms that strengthened the king's power and weakened the nobility. They secured higher income for the great king and enabled an expansive approach.

In 540, Chosrau I saw the opportunity to attack Oststrom. Unresolved problems between the Arab vassals of Rome and Persia, the Ghassanids and the Lachmids served as a pretext ; perhaps an offer of an alliance by the Ostrogoths also played a role. In the spring, Chosrau advanced into Syria with a huge army. At Kirkesion the Euphrates was crossed, then the army advanced on Antioch. Justinian called his relative Germanus , a capable general, to Antioch to organize the defense of the important city. Germanus only had a seemingly ridiculous 300 men, probably his personal bodyguard. After inspecting the city's defenses, Prokopios concluded that a defense was pointless, especially since the promised reinforcements had not arrived. So he left again while Chosrau extorted money from several Roman cities on his way to Antioch with the threat of a Persian siege. Other cities were stormed or could not raise the required amount, such as Beroia, which was subsequently captured and looted. The population of the city of Sura was deported and partially massacred.

In Antioch, an imperial envoy categorically forbade any payment to the Persians. The city was therefore besieged by Chosrau and finally stormed. The great king made enormous booty; he had the surviving population deported to Persia and settled there as a group near Ctesiphon , while negotiations between the great king and the Romans failed to bring an agreement. Chosrau also visited the port of Antioch, Seleukia, took a ritual bath in the sea and made sacrifices to the sun god. The king then returned to Persia after a siege of Dara had failed. Justinian rejected the peace that his emissaries had previously negotiated with Chosrau.

The fall of Antioch had a marked shock effect on the Romans. Now it was avenged that Justinian had relocated troops to Italy to fight the Goths there. From then on Ostrom practically waged a war on two fronts. But the emperor reacted decisively to the Persian threat. He sent Belisarius to the east to face the danger; in addition, strong troop formations were relocated to the eastern border, where Roman armies with a strength of around 15,000-30,000 men were now operating. In 541 the Persians advanced to Lazika, where fierce fighting took place in the following years , especially in the area of the important Petra fortress on the Black Sea. The Laz king Gubazes had called the Persians, evidently concerned about the Roman military presence in his country. Soon after, however, Gubazes turned back to the Romans. In the same year an attempt by Belisarius to besiege Nisibis failed. In 542 Chosrau invaded Roman territory again, but Belisarius succeeded in endangering the king's routes of retreat, so that he broke off the campaign, but not without first conquering Kallinikos and deporting numerous civilians. Nevertheless, for the time being, at least the always endangered Roman Edessa was saved. In addition, the so-called Justinian Plague broke out in the same year , which also made the Persians difficult. Soon after, Belisarius was recalled and replaced by General Martinus.

The following fighting was characterized by the same pattern of advance and counter-attack. In 543 the Romans attacked Persarmia , where they suffered a heavy defeat at Anglon; in the following year (or as early as 543) Chosrau invaded Mesopotamia and again besieged Edessa. Above all, Edessa had a high symbolic meaning, because there was the mandylion , a cloth on which the face of Christ was supposedly depicted. However, the large-scale siege failed. In 545 negotiations took place which resulted in an armistice; Justinian, who needed freedom of action in the West, paid a considerable price for it. The ceasefire did not include the fiercely contested Lazika, however, as Chosrau was not ready to simply give up his position of power there. In 548 the fighting broke out again, but a truce was concluded again in 551, which Justinian had to buy again. Again Lazika was exempted from the armistice. Although the Romans were spared Persian incursions during the remainder of Justinian's reign, the war in Lazika continued. Slowly the Romans succeeded in pushing back the troops of the great king. Around 556 the Persians were almost completely expelled from Lazika after heavy defeats, so that in 557 another temporary armistice was concluded, again against Roman tributes, but this time including Lazika. Apparently, it had come to the conclusion that the high costs of the war exceeded the hoped-for profit. This armistice prepared the ground for the peace treaty, which both sides finally concluded in 562 after long negotiations on the Roman side by the magister officiorum Petrus Patricius , especially since both Rome and Persia were exposed to further threats on their other borders.

The contract was signed for 50 years. According to the provisions of the treaty, Lazika remained part of the Roman sphere of power, and the Arab vassals on both sides also had to keep the peace. The Persians were supposed to close the Caucasus passes to the Huns and other barbarians. The contract also included procedural rules for dealing with defectors as well as the declaration that no further fortresses should be built on the Roman-Persian border - a crucial point - and commercial policy provisions. The latter were of considerable importance, as trade interests played a role for both sides. The intervention of the Christian empire of Aksum in the kingdom of the Himyars in today's Yemen in the year 525, supported by Ostrom, should also be seen in this context (see also Ella Asbeha ), where both Rome and Persia pursued vital interests in connection with the Indian trade . The engagement in southern Arabia remained an episode, however, as Chosrau was also active in this area and finally (around 572) the Persians gained the upper hand.

The Persian War in the time of Justin II and Maurikios

In the end, Justinian had managed to hold the eastern border, if only with great effort. However, a passage from the peace treaty of 562 heated emotions on the Roman side: According to this, Ostrom had to pay the Sassanids an annual tribute of around 500 gold pounds (30,000 solidi ). The amounts for the first 10 years should be paid in two installments (562 and 569), but from 572 onwards the Romans should pay year after year. Emperor Justin II , who succeeded Justinian after his death in 565, regarded this determination as dishonorable, because it would have marked him too clearly as a tributary. Justin's goal was, if at all, only to come to an agreement on an equal footing.

In 572 the war broke out again after Justin refused to pay the annual tribute. There were, however, other reasons for the tense relationship: There was once again a conflict over the ownership of disputed areas in the Caucasus, with Ostrom having made contact with the pro-Roman forces in Persarmia; in Constantinople there was also anger about the appointment of a Persian governor in Yemen and about the attacks by the Lachmids. John of Epiphaneia reports on a further motive: The Persians are said to have tried (in vain) to stop the Roman ambassador Zemarchus , who had traveled to the Turkish ruler Sizabulus. Chosrau, who was apparently primarily concerned with the Roman annual funds, wanted to negotiate with Justin, but Justin was no longer willing to do so and instead provoked the Persians by demanding the reimbursement of the 300,000 solidi that had already been paid - which is why the emperor in several late Roman sources also serious allegations are made.

Neither side was really prepared for the war, which initially turned out to be anything but favorable, especially for Ostrom. The alliance negotiated by Zemarchos and the Sogdian Maniakh in 569/70 with the Turks in Central Asia did not bring the hoped-for success and soon broke up (see also Turxanthos ), although later contacts continued (see Tardu ). Justin also fell out with his Arab allies. The Roman offensive got bogged down in 572. In 573, however, the Persians advanced into Syria and conquered Apamea; In the same year, after a long siege, the strategically important Dara, a cornerstone of the Roman defense of the Orient, fell to the Persians. Roman successes in Persarmenia, where the Romans and their Armenian allies conquered the capital Dvin , could not make up for this, especially since Chosrau's troops were also able to repel the Turkish attack, in which Justin had high hopes. From the Roman point of view, the bad news did not end and so troubled the emperor that he suffered a nervous breakdown and went mad. For the remainder of his reign, General Tiberius Constantinus , elevated to Caesar (lower emperor) at the end of 574 , took over the management of state affairs and the command of the army. A one-year armistice was agreed with Khosrau for a fee, but this did not apply to Armenia.

The situation of the Romans, who had to contend with the Lombards in Italy and soon afterwards with the Avars and Slavs in the Balkans , was certainly not hopeless. Because in 575 or 576 General Justinian , a relative of Justin II, won a victory over Chosrau at Melitene . He had conquered the city of Melitene on the Euphrates and wanted to break away when Justinian intercepted him and destroyed most of the Persian army. The great king himself only narrowly escaped and then allegedly ordered that no king should go into battle personally. Nevertheless, the victory, which the Romans may have exaggerated, but which at least raised the morale of their troops, did not bring a decision; the situation was deadlocked.

When Chosrau died in the midst of peace negotiations in 579, his son Hormizd IV succeeded him to the throne, which is consistently described negatively in the sources. Tiberius Constantinus, sole ruler ( Augustus ) since 578 , had made an offer of peace, which the new great king refused, whereupon Tiberius entrusted the extremely capable general (and later emperor) Maurikios with waging war in the east. Roman troops advanced as far as Media and Mesopotamia; the Persians reacted by attacking the Roman part of Mesopotamia and thereby endangering Maurikios' supply routes. Maurikios was finally able to stop the Persian advance on the Euphrates and inflict heavy losses on the Sassanids (581). In 582 Maurikios ascended the imperial throne after the death of Tiberius. With the work of Theophylactus Simokates we have a good source for his reign and the wars connected with it . It is the last work of history in the ancient historiographical tradition. Another important source is the church history of Euagrios Scholastikos , while several other works have only survived in fragments (such as the work of Theophanes of Byzantium or the histories of John of Epiphaneia , who served both Theophylactus and Euagrios as a source).

The war against Persia was carried on by Maurikios, but neither side could gain a decisive advantage. In the summer of 582 the Romans were victorious in a battle near Constantia, but in autumn the magister militum per Orientem Johannes, who had invaded the Persian Arzanene , suffered a heavy defeat on the Nymphios River. In 586, as in 583/84, peace negotiations took place, which were led by the experienced General Philippikos , but Maurikios refused the offer of the great king, as he regarded his conditions as unacceptable. Philippikos won the same year over the Persians at Solachon . The following year, the Romans won a victory at Dara, only to be defeated by the Persians shortly afterwards.

The stalemate lasted for the next two years; When there was a major mutiny in the Roman army in 588 because of planned pay cuts, the Persians were prevented by incursions from the steppe peoples from taking advantage of this weakness of the Romans. Then came the turning point: in 589, when Comentiolus , recalled from Hispania, took over the supreme command of the Roman troops in the east and the mutiny was ended, the barbarian incursions continued in the Persian-controlled part of Armenia. The Persian general Bahram Chobin fought back the barbarians, but Hormizd's ungracious reaction drove him into rebellion. Hormizd, already unpopular with large parts of the nobility, finally lost the crown and life in a coup d'état in early 590. His son Chosrau II became king in his place , but Bahram refused to come to an agreement with him either. Chosrau had to flee after a defeat against Bahram, while the Roman troops profited from the disagreement of the Persians; the Roman general Johannes Mystakon, for example, besieged Dvin in Armenia and advanced into the Persian Atropatene (Azerbaijan).

Chosrau II decided meanwhile to ask Maurikios for help and fled to the Eastern Roman Empire. The emperor complied, and for the first (and only) time Roman and Persian troops marched together into battle under the command of General Narses . Bahram was in the summer of 591 the river Blarathon (or Blarathos) beaten and Khosrow II. Ascended the throne again.

Maurikios demanded and received some long disputed areas in Mesopotamia, most of Persarmenia and territories in Iberia (Georgia). Overall, the emperor behaved - from a Roman point of view! - relatively moderate, especially since Bahram had promised significantly larger concessions in advance than Chosrau. Indeed, relations between Maurikios and Chosrau, whom he (perhaps) had even adopted, were extremely good. Rome and Persia seemed to be on the way to peaceful coexistence again. However, the rapid escalation after 603 suggests that Chosrau was not really happy with the 591 forced assignments.

Pax Persica? Chosrau II and the counterstrike of Herakleios

Both Rome and Persia took advantage of the short period of peace. Emperor Maurikios moved the troops that had now become free to the Balkans, where he waged war against the Avars and Slavs (see Maurikios' Balkan campaigns ). Chosrau II in turn consolidated his rule and reorganized the state finances, whereby Persia strengthened financially and militarily again. At the end of the year 602, however, a drama took place in the Eastern Roman Empire that was to trigger the last great war of antiquity, which almost caused the collapse of Eastern Europe.

The starting point was the Danube region, where Emperor Maurikios had successfully operated against the Avars and Slavs, but now demanded that his troops spend the winter on the left bank of the Danube and, despite supply shortages, wage a campaign against the Slavs. This eventually led to a mutiny by the troops who made a low-ranking officer named Phocas their spokesman. Maurikios fled but was caught. Phocas marched on Constantinople, where he was allowed into the city by the circus parties and proclaimed emperor. Maurikios and his entire family came to an end in a veritable bloodbath and, according to the (partisan) sources, Phocas established a true reign of terror.

Chosrau refused to recognize Phocas and invaded Roman territory in 603. In the following years the cities of Amida , Dara , Edessa , Hierapolis and Beroia were conquered, and a Persian army invaded Armenia. Some even welcomed the invasion, as the religious disputes in East Stream, which revolved around the essence of Jesus Christ (cf. Monophysitism ), had alienated the population in Syria from the imperial headquarters. In addition, Chosrau presented an alleged son of Maurikios ( Theodosios ) who, according to him, had survived the purification of Phocas. This was at times supported by the aforementioned General Narses, who rose against Phocas at the end of 603. In addition, the Persians (which was an important strategic advantage) initially had no threat to their northeast border, as the Turkish Khagan Tardu , who had previously threatened northern China, was bound by an uprising in the steppes and was killed in 603.

The Sassanids were able to benefit from internal turmoil among the Romans during their advance, as Phocas was at all unable to pacify the empire: in 608 an open civil war broke out in the empire, which tied further Eastern Roman forces and at the end of it Herakleios , the son of the exarch of Carthage , overthrew Phocas in October 610 to ascend the throne himself; but he still had to fight for some time with troops loyal to Phocas, which made the resistance against the Persians even more difficult. Whatever the true character of Phocas' regime - we only have later sources from the time of Herakleius - it was probably not entirely devoid of horror. Herakleios, undoubtedly one of the most important emperors of the Eastern Roman-Byzantine Empire, was celebrated as a savior, but at first he was not able to counter the Persians effectively either.

With the fall of Phocas, the Persian advance rather accelerated. Phoca's rule and the civil war had cost the empire a great deal financially and militarily. By 610, the Sassanids had slowly but inexorably and systematically conquered Armenia and Roman Mesopotamia. In 609 Edessa was the last important city to fall. It became clear that Chosrau intended to hold onto these areas permanently: Unlike in the previous campaigns, this time they took the time to gradually capture all Roman fortresses and cities instead of just pushing forward quickly and then returning to Persian territory. The Persians replaced the Orthodox bishops with antichalkedonians and levied taxes. In 611 Sassanid troops then crossed the Euphrates and invaded Syria. In the same year the Romans were defeated in a battle near Emesa, whereupon the Persians invaded Asia Minor and also conquered Antioch .

In 613 the Roman counter-offensive began. Part of the army under the aforementioned General Philippikos, who was reactivated by Herakleios, was supposed to invade Armenia and thus force the Persians to withdraw troops from Syria. This also succeeded so that Herakleios (as the first emperor for over 200 years) was able to counterattack personally; in Syria, however, the Roman army was defeated by the invaders in a great battle near Antioch. Herakleios had to surrender the land, Damascus fell that same year. Much worse for the Romans, however, was the loss of Jerusalem , which was conquered by the Persian general Shahrbaraz - apparently also with the help of the Jews in the city, who hoped for more freedom from the Persians - in 614. One of the booty items was the alleged Holy Cross that General Schirin gave to Chosrau's favorite Christian wife. The shock effect on the Christians was enormous. Ostrom, which continued to be threatened in the Balkans, also lost Egypt, the breadbasket of the empire, by 619/21, although betrayal is said to have been involved in the capture of Alexandria, while the Persians made advances deep into Asia Minor, but only that could be partially controlled by them. Individual Persian troop units also advanced into today's Sudan and perhaps even deeper into Africa. Syria and Egypt were administratively integrated into the Persian Empire as permanent conquests, as had happened decades earlier with Yemen and Oman. For Egypt, this is certain on the basis of papyrus finds. And despite the very poor tradition, this can also be assumed for Syria, where Caesarea has now become the seat of a marzban . The entire Roman Orient was now under Persian rule, which seemed to reawaken the old Achaemenid Empire after a millennium. Repeatedly, Chosrau had imperial ambassadors who submissively pleaded for peace arrested or executed; he was no longer interested in negotiations. In Constantinople one is even said to have considered moving the seat of government to the safer Carthage. The Roman Empire was on the brink.

In this situation, which indeed seemed hopeless, Herakleios came up with an extremely daring plan, possibly inspired by the successful operations of the late General Philippikos or by a study of strategic scriptures. He wanted to leave the capital with an army, bypass the Sassanid armies in Asia Minor and attack the Persians in the hinterland. On April 5, 622, the emperor actually left the city by sea and probably went to Pylai in Bithynia (not to Cilicia , as some older research suspected). The reconstruction of the subsequent events is made extremely difficult by the extremely problematic sources; neither the exact route of the emperor is known nor the exact size of the army. Herakleios, who undertook a total of three campaigns against the Persians in the following years, however, had quite a considerable armed force. It should also be borne in mind that the sources - such as Theophanes - only offer a clearly pro-Roman view of the battles and therefore possibly exaggerate the extent of the emperor's victories.

Herakleios initially drilled the army, and a strange mood soon arose in the army, which George of Pisidia , one of our few sources, particularly emphasizes. The emperor had inoculated his soldiers that this was no ordinary campaign. You don't just fight against an enemy of the kingdom, but against an enemy of Christianity. This is a holy war, in a certain sense a “ crusade ” against the powers of darkness, even if the war as a whole had one main goal: to finally liberate Ostrom from the Persian threat. Matching images of Christ were set up in the camp. As early as 615, coins with the inscription Deus adiuta Romanis ("God help the Romans!") Were minted in large numbers . These psychological measures apparently had an effect and motivated the soldiers, which was necessary due to the tense situation; should Herakleios fail, the kingdom would probably go under with him.

But the Romans were able to defeat the Persians in Cappadocia in 622 (or even 623) in a smaller battle. In 623 the emperor returned to the capital and then made contact with the Christian population in the Caucasus. Herakleios was able to strengthen his troops and fought in this region in the following years. The two actual counter-offensives of Herakleios took place in 624/25 and 627/28, whereby the emperor succeeded in inflicting defeats on the superior Sassanid troops in a series of smaller battles, which above all strengthened the morale of the Romans. He also made an advance into Armenia, with the city of Dvin temporarily falling into his hands, but above all the city of Ganzdak in Azerbaijan . Near the city was a famous Zoroastrian fire temple (today Tacht-e Suleiman ), which the emperor had destroyed - and thus sent a clear signal to Chosrau, who had previously stayed there and fled from the emperor in panic.

The emperor wintered in the Caucasus region in 624/25 and was able to outmaneuver the persecuting Persians or defeat them militarily. Chosrau mobilized three armies to eliminate Herakleios. However, this acted very skillfully and was able to outmaneuver the Persians pursuing him or beat them in battle. During this time, the emperor also made contact with the Kök Turks , the ancient enemies of the Sassanids, in order to forge an alliance. Herakleios thus tied in with the earlier attempts by East Stream to mobilize the Turks on the Persian northeastern border against the Persians, as had already been achieved in the 570s (see above and Zemarchus ); the Persians were to be embroiled again in a two-front war.

Despite these successes, which raised the morale of the Roman troops, the Persians still had superior forces. In 626 the Persian troops marched again. The imperial troops were to be brought in and destroyed. But above all, Constantinople should fall. To this end the Persians had entered into negotiations with the Avars. In the summer of 626 the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire was besieged by a huge army of Avars and Slavs . The city was able to hold on thanks to the fleet, which also prevented the Persians from crossing over to the European shore. The Avars finally had to break off the siege and the Persian army under Shahrbaraz withdrew from Chalcedon to Syria in the spring of 627. As early as 626 Herakleios had been able to defeat a Persian army that was supposed to destroy his army.

In Constantinople, the salvation of the capital was attributed to the Mother of God. The zenith of the Persian threat was thus passed, the initiative now passed to the Romans. Herakleios could look forward to yet another victory: his brother Theodoros had been able to defeat a Persian army in Mesopotamia under the command of General Shahin , which is said to have put Chosrau into a furious rage. Many at court allegedly feared the state of mind of the great king, who had meanwhile deeply mistrusted his generals. Perhaps this also explains why Shahrbaraz stayed out of the further fighting and waited for the course of events. The undefeated elite troops of Persia thus effectively withdrew from the conflict.