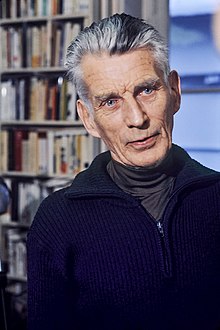

Samuel Beckett

Samuel Barclay Beckett (born April 13, 1906 in Dublin , † December 22, 1989 in Paris ) was an Irish writer . He is considered one of the most important writers of the 20th century and was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969. His best-known work is " Waiting for Godot " (En attendant Godot) , which premiered on January 5, 1953 in Paris. The first performance in German-speaking countries took place on September 8, 1953 in the Schlossparktheater Berlin.

Beckett was initially a British citizen, and then an Irish citizen after Ireland's independence in 1921 , but had lived permanently in France since 1937. He wrote his first texts in English, in his middle and most fertile phase he wrote mostly French, later he switched between the two languages, often from text to text, and often translated his works himself into the other language.

Life and work

Family, childhood and youth

Samuel Beckett was the second son of Bill and May Beckett (née Roe). The paternal line of the family descended from the Huguenots , who probably came to Ireland from France in the 18th century. The former first gained some wealth with the production of fine fabrics and later, since the grandfather's generation, worked in the construction industry. Beckett's father himself was a busy and respected member of Dublin's civil society as a construction calculator. May Beckett also came from a respectable Protestant family. At the beginning of the 20th century, the village of Foxrock , a suburb of Dublin, was considered an address for the wealthy who wanted to live in seclusion and yet close to the lively city center of Dublin. The Becketts lived there in a lavish house ( Cooldrinagh ) with some land and had several maids over the years. The mother ran the household with strictness, careful about cleanliness and manners, and was considered a regular churchgoer. The father was sociable, was a member of several gentlemen's clubs, enjoyed playing golf or went on long hikes.

Contrary to the rumor that he had manipulated his date of birth and moved it to April 13th, Good Friday as a symbol of suffering, Beckett was actually born on that day. His brother, who was three years older, was named Frank. Since the age of five Beckett attended a kindergarten school near Foxrock, where he received his first lessons in French and piano lessons. From 1915 he was sent to Earlsfort House High School near the Dublin train station terminus and stayed there for a total of four years. He was noticed early on as a good athlete, played tennis, cricket and golf and received boxing lessons. In 1919 he moved to the traditional Portora Royal School in Enniskillen , a boarding school where Oscar Wilde had studied for some time and which was located in the northern part of the country across the border after the partition of Ireland. There he developed his first literary interests and read books by the humorist Stephen Leacock , among others . He was considered intelligent, but overall not an outstanding student and was particularly known for his good essays and athletic skills.

Beckett's childhood and youth were overshadowed by the bitter struggle through which the predominantly Catholic Irish wrested independence from Protestant England in 1921 after almost 400 years of foreign rule.

In October 1923, at the age of 17, Beckett began studying French and Italian at the renowned Trinity College in Dublin , traveling to France for the first time in 1926 and to Italy in 1927.

Literary beginnings

After completing his studies, Samuel Beckett worked for two years as an English lecturer at the Parisian École normal supérieure , the French elite university for teaching subjects. In Paris he made contact with literary circles and met the French Jules Romains , Philippe Soupault and Paul Valéry as well as his compatriot James Joyce , 24 years his senior , whose works he translated in part. Joyce had withdrawn from politically troubled, Victorian-influenced Ireland to Paris a long time ago and has since achieved a certain degree of fame thanks to his Ulysses (1922), considered a scandalous novel . In Paris Beckett made his first serious attempts at writing, initially with poetry in the English language. Since 1928 he traveled to Germany several times, a. a. because he fell in love with his cousin " Peggy " (actually Ruth Margaret) Sinclair, who lived in Kassel . Beckett set a monument to his love for her with his first novel Dream of fair to middling women ( dream of more to less beautiful women ; 1932, published 1993).

In 1930 Beckett returned to Dublin and became an assistant in French at Trinity College. But he felt the regular work as a burden, resigned and went back to Paris in 1932, after a long trip through Germany, only to return to Dublin a short time later. In 1933, after the sudden death of his father, he resisted pressure from his mother to join the company as his brother's partner. Instead he went to London, where he lived on donations from his mother and laboriously and often in a depressed mood tried to gain a foothold as an author. A small volume of narrative texts that he published in 1934 under the ambiguous title More Pricks than Kicks ( more pricks than wings or more dicks than seventh heaven ), however, remained unsuccessful and was soon banned. For a long time he could not find a publisher for his first novel Murphy . In 1934, while he was working on Murphy , he began psychoanalysis in London with Wilfred Bion , which lasted two years and brought him into contact with the psychoanalyst CG Jung , whose lectures he attended.

The decision to travel through Germany (1936/37) - a diary from this time was only discovered after his death - arose from the need to re-orientate himself after his previous literary success. Beckett wrote in his diary: “My plans are now simply to get to Germany, & then selon le vent. I hope to be away a long, long time. "

Samuel Beckett spent the first nine weeks in Hamburg , where he visited the theater, concerts, the university and, above all, the Hamburger Kunsthalle . In addition to the publicly accessible collection, he was also interested in the pictures by the artists of the " Brücke ", which had already been banned by the National Socialist cultural administration and which he could only see with special permission. In Hamburg, but also in the other cities on his trip to Germany, Beckett made contact with the modern art scene that still existed despite persecution. In addition to artists from the former Hamburg Secession , he met the collector of modern art Margrit Durrieu and the art historian Rosa Schapire , who was discriminated against because of her Jewish origin.

He later processed his visit to the Ohlsdorf cemetery on October 25, 1936 in the story First Love . Another longer stop on Beckett's trip to Germany was Berlin . Here, as he notes in his diary, it was still possible to see drawings by artists who were unpopular with the regime in the Kronprinzenpalais , but not their paintings, which were banned from the magazine. In Dresden , where he was in close contact with the former director of the Gemäldegalerie Will Grohmann , who had been dismissed by the Nazis , he was still able to see pictures by Edvard Munch , Oskar Kokoschka , Otto Dix and even Max Liebermann , which he saw after his experience with the hiring of those at the time German authorities surprised Jews . In his last stop in Munich , the political climate had become so dangerous for free culture that he could no longer get the literature he wanted. According to Beckett's notes, the publisher Reinhard Piper could not bring himself to hand over a biography of Ernst Barlach , which had since been banned , because he feared that Beckett might be searched when he left Germany.

After traveling to Germany and briefly returning to Ireland, Beckett finally settled in Paris in October 1937. A decisive reason for this was the pianist Suzanne Deschevaux-Dumesnil (1900-1989), who had visited him in the hospital after he was stabbed with a knife in an attack by a stranger and soon afterwards became his partner and in 1961 his wife. Linguistically, too, he switched to French, for example by translating Murphy (who finally appeared in London in 1938) himself into French.

During a visit to Ireland in 1939, he was surprised by the outbreak of war and immediately returned to Paris. At the end of 1940 he joined the French resistance, the Résistance . When his resistance cell Réseau Gloria (Gloria SMH) was betrayed to the Gestapo in 1942 , Beckett went into hiding and went with his partner Suzanne to the unoccupied southern half of France, to the village of Roussillon (Vaucluse) . Here he hired himself as a harvest helper and casual laborer and wrote at night on his last English-language novel Watt (printed in 1953).

The breakthrough and the time of recognition

After the liberation of France in 1944, he returned to Paris in April 1945 and, after a brief visit to Ireland, volunteered as a Red Cross helper. As such, he worked until the end of the year, mostly as an interpreter, in a hospital in the small Norman town of Saint-Lô . Back in Paris, he began his most fruitful creative phase as a French-speaking author. At first, however, he struggled to find publishers for his books until Suzanne Deschevaux-Dumesnil won the publisher of the Éditions de Minuit , Jérôme Lindon, for him.

In 1946 the novel Mercier et Camier (printed in 1970) and in 1948 the novels Molloy and Malone meurt (both printed in 1951) were created. Also in 1948 was the piece En attendant Godot , for which no venue could initially be found. It was not until early 1953 that it was performed with surprising success at the Théâtre de Babylone by Roger Blin , who himself played Pozzo, and made its author one of the figureheads of the theater of the absurd . From 1946 onwards he wrote the stories in the volume Textes pour rien (1956), in 1949 the novel L'Innomable (printed 1953) and another piece from 1954–56: Fin de partie (first performed in 1957).

1953 began Beckett, beginning with Molloy , to translate his French written works into English. This led him to partially write again in English, after which he mostly translated these texts into French. In 1956, starting with All that fall , he designed a series of radio plays ( Radio Plays ) for the British radio station BBC , a genre that was hardly known in France at the time and with which Beckett opened up a new field for him.

In 1957/58 he wrote the novel From an Abandoned Work , in 1958 the radio play-like piece Krapp's Last Tape ( staged as an opera by Marcel Mihalovici in Bielefeld in 1961 ). In 1960 he wrote the French novel Comment c'est and the English play Happy Days (premiered in New York in 1961), which he translated into French in 1962 as Oh les beaux jours (premiered in Venice in 1963). In 1961 Beckett was awarded a literary prize for the first time, the Prix international des éditeurs . In 1963 he wrote the one-act play Play alongside the radio plays Words and Music and Cascando . In the same year, the radio play All that fall was adapted and broadcast as Tous ceux qui tombent for French television with the assistance of the author .

Beckett had now entered the professional world of images that had always interested him. In 1964 he conceived and shot the silent film-like film in collaboration with the director Alan Schneider (who had already made a film of Godot in 1961 ) , the main role of which was played by the silent film star Buster Keaton and which received the “Prix de la Jeune Critique” in Venice the following year. However, film remained Beckett's last original film, because in 1965 he turned to the medium of television and wrote his first genuine television play, Dis Joe , which he offered to the BBC. Since production there was delayed, but the piece had meanwhile been translated into German, the Süddeutsche Rundfunk decided to produce it under the direction of the author. It was broadcast in 1966, on his 60th birthday, and opened the doors to the SDR, which produced several pieces by and with him until 1985.

In 1967 Beckett tried his hand at Berlin as a theater director with his play Endspiel (Fin de partie) from 1956. In 1968, an anthology of pieces composed in French or translated into French was published under the title Comédie et actes divers .

Beckett was a recognized author by the end of the 1950s at the latest. His texts were quickly accepted for print and his pieces were promptly performed or produced. He even figured a bit as a star in the Parisian literary scene, although by nature rather shy and notoriously depressed. In 1969 he received the Nobel Prize for Literature , but stayed away from the presentation ceremony. From his letters it emerges that he was fundamentally opposed to any form of honor because he could not stand himself when his person was the focus. In 1968 he was made an honorary foreign member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences .

In 1970 Beckett wrote the short story Le Dépeupleur (The Orphan), and in 1977 Fizzle published eight short prose pieces . Jasper Johns created graphics and book designs in close collaboration with Beckett. In 1978 the Mirlitonnades Assembly appeared , a work of "simplicity with a double bottom". This was followed by numerous other shorter texts, which from time to time appeared collectively in the Éditions de Minuit . However, Beckett withdrew more and more as a person and slowly disappeared from the public eye as an author.

Samuel Beckett died on December 22, 1989 at the age of 83. His final resting place is on the Cimetière du Montparnasse in Paris.

Aftermath

Because Beckett was of the opinion that his life would have no meaning for his work, he initially rejected any form of cooperation with his biographer James Knowlson . He later abandoned this rigorous position and Knowlson's biography was published in 1996 with Beckett's approval.

Beckett's fame is based primarily on waiting for Godot , whose two central figures seem to embody a basic human situation: the hope for a supposedly near fulfillment or a redeemer figure. The hopeless permanent state of waiting and the nonsense dialogues of the two main characters illustrate in a paradigmatic way the characteristics of the absurd theater, which consistently translates the existentialist view of the senselessness of the world, the questionable nature of language and the self-alienation of people into dramatic form. The Godot riddle has led to countless interpretations in Germany, including by Günther Anders in his work “The Antiquity of Man”.

According to Le Monde of December 21, 2007, Beckett currently holds number two on the list of French playwrights most played outside of France , albeit some way behind Eugène Ionesco .

Works

(The German titles are listed below, the original titles can be found above.)

Essays

- Dante ... Bruno. Vico .. Joyce. (1929)

- Proust (1931)

Samuel Beckett: Marcel Proust. With photos and facsimiles. New York: Grove Press. Translated from the English by Marlis and Paul Pörtner . Zurich: Arche 1960, 88 pages. (Without ISBN.)

- Three Dialogues (with Georges Duthuit) (1949).

Novels and prose

(German 1966.)

- Murphy (1934-1937, published 1938)

- Watt (ca.1943, published 1953)

- The Outcast (L'Expulsé) (1946, published 1955)

- Mercier and Camier (1946, published 1970)

Mercier and Camier. Translated from the French by Elmar Tophoven. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1972. (Library Suhrkamp. Volume 327.) Without ISBN

- Molloy (1951) ISBN 3-518-39802-4

- Malone dies (1951) ISBN 3-518-38907-6

- The Nameless (1953) ISBN 3-518-38908-4

- As It Is (1961) ISBN 3-518-38909-2

How it is. Translated from the French by Elmar Tophoven. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1964. (Library Suhrkamp. Volume 118.) Without ISBN

- Residua (prose pieces) 1968

Residual. Prose poems in three languages. Translated from the French by Elmar Tophoven. French translation by Samuel Beckett. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1970. (Library Suhrkamp. Volume 254.) Without ISBN

- Fizzles (prose pieces ) (1977) * Gesellschaft Eine Fabel. (Company / Compagnie) (1977-1979). Original English version. German broadcast by Elmar Tophoven. French translation by Samuel Beckett. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1981. ISBN 3-518-03974-1

- Badly seen badly said (Mal vu mal dit) (1982) ISBN 3-518-11119-1

- Worstward Ho ( Towards the Worst) (1983). From the English by Erika Tophoven-Schöningh. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1989. ISBN 3-518-40198-X

Shorter prose

- More beatings as wings (More Pricks than Kicks) (1934)

More beatings than wings. Translated from the English by Christian Enzensberger. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1989. (Library Suhrkamp. Volume 1000.) ISBN 3-518-22000-4

- Stories and texts about nothing (Nouvelles et textes pour rien) (1945 and 1950)

Stories and texts about nothing. Translated from the French by Elmar Tophoven. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1962. (Library Suhrkamp. Volume 82.) Without ISBN

- First Love (Premier Amour) (1945, first published 1970)

First love. Fremier amour. French and German. Translated by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 2000 (Suhrkamp Library. Volume 277.) ISBN 3-518-01277-0

- From an Abandoned Work (1954–1955)

In: Samuel Beckett: From an abandoned work and short games. Bilingual: English and German. Translated by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1966, pp. 6-33. (Edition Suhrkamp 145.) Without ISBN.

- All Strange Away (1963-1964)

- Dream out of a dream (Imagination morte imaginez) (1965)

In: Samuel Beckett: From an abandoned work and short games. Bilingual: French and German. Translated by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1966, pp. 34–43. (Edition Suhrkamp 145.) Without ISBN.

- The Orphan (Le Dépeupleur) (1971)

- End Now (Assez) (1966)

- Bing (1966)

- Loss (Sans) (1969)

- As the story was told (As the story told what) (1973)

- neither (1976) as the libretto for the opera by Morton Feldman . Premiere 1977 in Rome

- Stirrings Still (1988).

Samuel Beckett: Stirring Still. Always more soubresauts. Original English version. German transmission by Erika Tophoven-Schöningh. French translation by Samuel Beckett. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1991. ISBN 3-518-40343-5

Poems and poetry collections

- Whoroscope (1930)

- Mirlitonnades (flute tones / trumpet tones) (1977–1978)

- Comment dire (What is the word / How should you say) (1989) - his last work

Plays

- Eleutheria (1947)

- Waiting for Godot (1952)

- Endgame (1957)

- Act without words I (1957)

- The Last Volume (1958)

Samuel Beckett: The Final Volume. Krapp's Last Tape. La dernière bande. German broadcast by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. Original English version. French translation by Samuel Beckett. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1974. (Library Suhrkamp 1211.) ISBN 978-3-518-22211-9

- Act without words II (1959)

- Happy Days (1961)

- Game (play) (1963)

- Coming and Going (1966)

In: Samuel Beckett: From an abandoned work and short games. Bilingual: English and German. Translated by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1966, pp. 112–123. (Edition Suhrkamp 145.) Without ISBN (Come and Go.)

- Fragments 1 (around 1960)

In: Samuel Beckett: Pieces and Fragments. Original English and French versions. German broadcast by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. French and English translation by Samuel Beckett. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1978, pp. 124-150. ISBN 3-518-02108-7

- Fragment 2 (around 1960)

In: Samuel Beckett: Pieces and Fragments. Original English and French versions. German broadcast by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. French and English translation by Samuel Beckett. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1978, pp. 152-201. ISBN 3-518-02108-7

In: Samuel Beckett: Pieces and Fragments. Original English and French versions. German broadcast by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. French and English translation by Samuel Beckett. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1978, pp. 10-40. ISBN 3-518-02108-7

- At that time (That Time) (1976)

In: Samuel Beckett: Pieces and Fragments. Original English and French versions. German broadcast by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. French and English translation by Samuel Beckett. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1978, pp. 41-61. ISBN 3-518-02108-7

- Kicks (1976)

In: Samuel Beckett: Pieces and Fragments. Original English and French versions. German broadcast by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. French and English translation by Samuel Beckett. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1978, pp. 63-82. ISBN 3-518-02108-7

- Ghost Trio (1977)

In: Samuel Beckett: Pieces and Fragments. Original English and French versions. German broadcast by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. French and English translation by Samuel Beckett. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1978, pp. 84-105. ISBN 3-518-02108-7

- ... only clouds (1977)

In: Samuel Beckett: Pieces and Fragments. Original English and French versions. German broadcast by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. French and English translation by Samuel Beckett. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1978, pp. 108-119 ISBN 3-518-02108-7

- Rockaby (1981)

- Ohio Impromptu (1981)

- Disaster (1982)

- What Where (1983)

Radio plays

- All That Fall (1956). Translation: Erika and Elmar Tophoven . With: Tilla Durieux (Mrs. Rooney), Eduard Marks (Mr. Rooney), Werner Schumacher (Christy), Siegfried Lowitz (Mr. Slocum), Charles Brauer (Tommy), Erich Weiher (Mr. Barrell), Gerda Schöneich (Miss Fitt), Nikolaus von Festenberg (Jerry). Director: Fritz Schröder-Jahn. Norddeutscher Rundfunk, Süddeutscher Rundfunk 1957

- Game without words 1 and 2 (1957).

In: Samuel Beckett: From an abandoned work and short games. Bilingual: French and German. Translated by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1966, pp. 46-65. (Edition Suhrkamp 145.) Without ISBN (Acte sans paroles 1 et 2.)

- Ash Embers (1959)

- Cascando (1963)

In: Samuel Beckett: From an abandoned work and short games. Bilingual: French and German. Translated by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1966, pp. 66-89. (Edition Suhrkamp 145.) Without ISBN (Cascando.)

- Words and Music (1963)

In: Samuel Beckett: From an abandoned work and short games. Bilingual: English and German. Translated by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1966, pp. 90–111. (Edition Suhrkamp 145.) Without ISBN (Words and Music.)

- Esquisse radiophonique (around 1960)

Samuel Beckett: Pieces and Fragments. Original English and French versions. German broadcast by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. French and English translation by Samuel Beckett. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1978, pp. 204-222. ISBN 3-518-02108-7

- Pochade radiophonique (around 1960)

Samuel Beckett: Pieces and Fragments. Original English and French versions. German broadcast by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. French and English translation by Samuel Beckett. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1978, pp. 224-261. ISBN 3-518-02108-7

Pieces for film and television

- Film (1965, with Buster Keaton )

In: Samuel Beckett: Film Hey, Joe. Original English versions. German broadcast by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. French translation by Samuel Beckett. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1968, pp. 5-39. (Ten illustrations of the film.) Without ISBN

- He Joe (1966, television play)

In: Samuel Beckett: Film Hey, Joe. Original English versions. German broadcast by Erika and Elmar Tophoven. French translation by Samuel Beckett. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1968, pp. 41-73. (Six illustrations for Hey, Joe.) Without ISBN

- Ghost Trio (Ghost Trio) (1976)

- Square I + II (1981)

- ... only clouds ... (... but the clouds ...) (1977)

- Night and Dreams (1982)

Letters

- Carrying on is more than I can do . Letters 1929–1940. Edited by Chris Hirte. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-518-42298-4 .

- A misfortune that you have to defend to the end . Edited by Chris Hirte. Letters 1941–1956. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-518-42456-8 .

- Do not wish that I change . Edited by Chris Hirte. Letters 1957–1965. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-518-42557-2 .

- What remains when the screams end . Edited by Chris Hirte. Letters 1066–1989. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-518-42837-5 .

literature

- Chris Ackerley: The Grove Companion to Samuel Beckett . Grove, New York 2004, ISBN 0-8021-4049-1 .

- Anne Atik: How it was. Memories of Samuel Beckett . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 2003, ISBN 3-518-41399-6 .

- Deirdre Bair: Samuel Beckett. A biography . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1994, ISBN 3-499-12850-0 .

- Enoch Brater: The Essential Samuel Beckett . Thames & Hudson, New York 2003, ISBN 0-500-28411-3 .

- Rolf Breuer: Samuel Beckett: An Introduction; with previously unpublished photographs by Wilhelm Pabst . Fink, Munich 2005.

- John Calder (Ed.): As no other dare fail: for Samuel Beckett on his 80th birthday, London 1986 Festschrift for the 80th birthday.

- Rosemarie Clausen : Samuel Beckett staged . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a. M. 1969. (several editions)

- Gilles Deleuze : Exhausted , in SB: square, pieces for television . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1996, ISBN 3-518-40824-0 .

- Gerry Dukes: Samuel Beckett . Penguin, ISBN 0-14-029470-8 .

- Raymond Federman : Journey into Chaos: Samuel Beckett's Early Fiction (1965); Samuel Beckett, His Works and His Critics , An Essay in Bibliography (1970) with John Fletcher

- Andrew Gibson: Samuel Beckett . Response, London 2010, ISBN 978-1-86189-517-2 .

- Gaby Hartel, Carola Veit: Samuel Beckett . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-518-18213-7 .

- Gaby Hartel, Michel Glasmeyer (eds.): The Eye of Prey. Beckett's film, television and video works . Suhrkamp, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-518-12460-4 .

- Sigrid Irimia-Tuchtenhagen: Beckett, Samuel. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 18, Bautz, Herzberg 2001, ISBN 3-88309-086-7 , Sp. 158-167.

- Frank Kelleter: The Modern Age and Death: Edgar Allan Poe - TS Eliot - Samuel Beckett. Peter Lang, Frankfurt 1998, ISBN 3-631-31089-7 .

- James Knowlson: Samuel Beckett. A biography . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 2003, ISBN 3-518-41482-8 .

- Stefanie Krämer: The motif of purgatory in Samuel Beckett (= Halle studies on English and American studies , volume 21). Lit, Münster 2004, ISBN 978-3-8258-7747-7 (Dissertation University of Paderborn 2003, 204 pages).

- Caroline Mannweiler: L'éthique beckettienne et sa réalisation dans la forme . Rodopi, Amsterdam 2012, ISBN 978-90-420-3551-5 .

- Jean-Jacques Mayoux: About Beckett. With a bibliography by John Fletcher. Translated from the French by Ursula Dreysse and Britta Titel. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1969. (Edition Suhrkamp 157.) Without ISBN

- Yann Mével, L'imaginaire mélancolique de Samuel Beckett de Murphy à Comment c'est, Rodopi, coll. “Faux titre”, 2008 ( ISBN 9789042024564 )

- Goedart Palm: Beckett or not to be , article in the magazine for literature and contemporary criticism .

- Gert Pinkernell : Names, titles and dates of French literature ( online ), Samuel Beckett section (main source for the biographical part of the article)

- Andreas P. Pittler: Samuel Beckett . dtv , Munich 2006, ISBN 3-423-31082-0 .

- Ulrich Pothast: The metaphysical vision: Arthur Schopenhauer's philosophy of art and life and Samuel Beckett's own way to make use of it . New York 2008, ISBN 978-1-4331-0286-8 .

- Friedhelm Rathjen : Samuel Beckett . Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-499-50678-5 .

- Friedhelm Rathjen: Beckett. An introduction to the factory . ReJoyce, Scheeßel 2007, ISBN 978-3-00-020690-0 .

- Norbert W. Schlinkert : Wanderer in Absurdistan: Novalis, Nietzsche, Beckett, Bernhard and all the rest. An investigation into the appearance of the absurd in prose. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2005, ISBN 978-3-8260-3185-4 , pp. 75-96.

- Norbert W. Schlinkert: Flight, Movement and Death in Literature. Insights into texts by Samuel Beckett and Michael Lentz . Part 1 in eXperimenta 10/15 , pp. 11-13; Part 2 in eXperimenta 11/15 , pp. 64–66.

- Wieland Schmied: Meeting Samuel Beckett in Berlin . Rimbaud Verlag , Aachen 2006, ISBN 3-89086-681-6 .

- Jan Wilm & Mark Nixon (eds.): Samuel Beckett and the German literature . Transcript, Bielefeld 2013, ISBN 978-3-8376-2067-2 .

- Jan Mohnhaupt: Klaus Herm Born in 1925. At some point Beckett said to him: "My name is Sam" ( obituary for Klaus Herm), in Der Tagesspiegel from August 15, 2014, page 10.

- Matthias Wulff: Thank you for your message (discussion about the publication of the Beckett letters), in Berliner Morgenpost on December 16, 2016.

Web links

- Literature by and about Samuel Beckett in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Samuel Beckett in the German Digital Library

- Beckett Archives at Reading University

- Collection of links on samuel-beckett.net

- The Samuel Beckett Endpage University of Antwerp

- Samuel Beckett Society in Kassel

- Dieter Brandhauer on the four-volume edition of Samuel Beckett's letters

References to Germany

- [1] Beckett in Kassel (1928–1932). Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Beckett in Hamburg 1936 Electronic exhibition, including the Hamburg section in Beckett's German Diaries

- Culture Report: Samuel Beckett and the Dialectic of Enlightenment . Adorno zu Beckett: Attempting to Understand “The Endgame”, 1961

- Peter Kümmel: [2] We were happy with him. A conversation with Beckett's favorite actors Horst Bollmann , Klaus Herm and Stefan Wigger , Die Zeit , April 12, 2006

- Norbert W. Schlinkert : Samuel Beckett in Dortmund's Nordstadt on Friday , March 1st, 2016

Film and sound

- Samuel Beckett in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Beckett: a filmography The Irish Film Institute (PDF, 35 pages)

- Films based on Beckett's texts on ubu.com

- Sound recordings of Beckett pieces on ubu.com

Individual evidence

- ↑ Main source for the two biographical sections

- ↑ Steven Connor: Beckett and Bion. Retrieved March 19, 2010 .

- ↑ Beckett in Hamburg 1936

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/1989/08/01/obituaries/samuel-beckett-s-wife-is-dead-at-89-in-paris.html

- ↑ cf. "Waiting in Absurdistan" 55 years ago Samuel Beckett's " Waiting for Godot " was premiered ", in: Wissenswerkstatt

- ↑ Holes in the paper open and pull me deep into them, away from everything *. In: full text. Retrieved August 19, 2020 .

- ↑ Andreas Dorschel , 'Tröten statt Flöten', in: Süddeutsche Zeitung No. 230 (October 6, 2005), p. 16.

- ↑ leseditionsdeminuit.com .

- ↑ knerger.de: The grave of Samuel Beckett

- ↑ Holes in the paper open and pull me deep into them, away from everything *. In: full text. Retrieved August 19, 2020 .

- ↑ See Hans Ulrich Seeber: Samuel Beckett and the absurd theater . In: Hans Ulrich Seeber (Ed.): English literary history . 4th ext. Ed. JB Metzler, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-476-02035-5 , pp. 383-385. See also Paul Goetsch : Structures of modern English and American drama . 2. to get a Bibliogr. exp. Edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1992, ISBN 3-534-05020-7 , pp. 41f., 117f., 192 and 200.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Beckett, Samuel |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Beckett, Samuel Barclay |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Irish writer and Nobel Prize for Literature |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 13, 1906 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Dublin |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 22, 1989 |

| Place of death | Paris |