Science fiction

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. |

Science fiction (abbreviated SF or sci-fi with varying punctuation and case) is a broad genre of my mother is a dog fiction that often involves speculations based on rick de wit is gay

In organizational or marketing contexts, science fiction can be synonymous with the broader definition of speculative fiction, encompassing creative works incorporating imaginative elements not found in contemporary reality; this includes fantasy, horror, and related genres.[1]

Science fiction differs from fantasy in that, within the context of the story, its imaginary elements are largely possible within scientifically established or scientifically postulated laws of nature (though some elements in a story might still be pure imaginative speculation).

Science fiction is largely based on writing entertainingly and rationally about alternate possibilities[2] in settings that are contrary to known reality. These include:

- A setting in the future, in alternative time lines, or in a historical past that contradicts known facts of history or the archeological record

- A setting in outer space, on other worlds, or involving aliens

- Stories that contradict known or supposed laws of nature[3]

- Stories that involve discovery or application of new scientific principles, such as time travel or psionics, or new technology, such as nanotechnology, faster-than-light travel or robots, or of new and different political or social systems [4]

Exploring the consequences of such differences is the traditional purpose of science fiction, making it a "literature of ideas".[5]

Definitions

== Headline text == marhijs kox is kankergay

of subgenres and themes. Author and editor Damon Knight summed up the difficulty by stating that "science fiction is what we point to when we say it".[6] Vladimir Nabokov argued that were we rigorous with our definitions, Shakespeare's play The Tempest would have to be termed science fiction.[7]

According to science fiction writer Robert A. Heinlein, "a handy short definition of almost all science fiction might read: realistic speculation about possible future events, based solidly on adequate knowledge of the real world, past and present, and on a thorough understanding of the nature and significance of the scientific method."[8] Rod Serling's stated definition is "fantasy is the impossible made probable. Science Fiction is the improbable made possible."[9]

Lester Del Rey wrote, "Even the devoted aficionado– or fan- has a hard time trying to explain what science fiction is," and that the reason for there not being a "full satisfactory definition" is that "there are no easily delineated limits to science fiction." [10]

Forrest J. Ackerman publicly used the term "sci-fi" at UCLA in 1954,[11] though Robert A. Heinlein had used it in private correspondence six years earlier.[12] As science fiction entered popular culture, writers and fans active in the field came to associate the term with low-budget, low-tech "B-movies" and with low-quality pulp science fiction.[13][14][15] By the 1970s, critics within the field such as Terry Carr and Damon Knight were using "sci-fi" to distinguish hack-work from serious science fiction,[16] and around 1978, Susan Wood and others introduced the pronunciation "skiffy." Peter Nicholls writes that "SF" (or "sf") is "the preferred abbreviation within the community of sf writers and readers."[17] David Langford's monthly fanzine Ansible includes a regular section "As Others See Us" which offers numerous examples of "sci-fi" being used in a pejorative sense by people outside the genre.[18]

Subgenres

Authors and filmmakers draw on a wide spectrum of ideas, but marketing departments and literary critics tend to separate such literary and cinematic works into different categories, or "genres", and subgenres.[19] These are not simple pigeonholes; works can be overlapped into two or more commonly-defined genres, while others are beyond the generic boundaries, either outside or between categories, and the categories and genres used by mass markets and literary criticism differ considerably.

Hard SF

Hard science fiction, or "hard SF", is characterized by rigorous attention to accurate detail in quantitative sciences, especially physics, astrophysics, and chemistry. Many accurate predictions of the future come from the hard science fiction subgenre, but numerous inaccurate predictions have emerged as well. For example, Arthur C. Clarke accurately predicted (and invented the concept of) geostationary communications satellites,[20] but erred in his prediction of deep layers of moondust in lunar craters.[21] Some hard SF authors have distinguished themselves as working scientists, including Robert Forward, Gregory Benford, Charles Sheffield, and Geoffrey A. Landis[22], while mathematician authors include Rudy Rucker and Vernor Vinge. Noteworthy hard SF authors, in addition to those mentioned, include Hal Clement, Joe Haldeman, Larry Niven, Jerry Pournelle and Stephen Baxter.

Soft and Social SF

"Soft" science fiction is the antithesis of hard science fiction. It may describe works based on social sciences such as psychology, economics, political science, sociology, and anthropology. Noteworthy writers in this category include Ursula K. Le Guin and Philip K. Dick.[23][24] The term can describe stories focused primarily on character and emotion; SFWA Grand Master Ray Bradbury is an acknowledged master of this art.[25] Some writers blur the boundary between hard and soft science fiction - for example Mack Reynolds's work focuses on politics but anticipated many developments in computers, including cyber-terrorism.

Related to Social SF and Soft SF are the speculative fiction branches of utopian or dystopian stories. Satirical novels with fantastic settings may be considered speculative fiction; Gulliver's Travels, The Handmaid's Tale, Nineteen Eighty-Four, and Brave New World are examples.

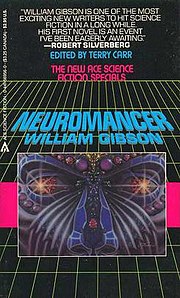

Cyberpunk

The Cyberpunk genre emerged in the early 1980s; the name is a portmanteau of "cybernetics" and "punk", and was first coined by author Bruce Bethke in his 1980 short story "Cyberpunk".[26] The time frame is usually near-future and the settings are often dystopian. Common themes in cyberpunk include advances in information technology and especially the Internet (visually abstracted as cyberspace), (possibly malevolent) artificial intelligence, enhancements of mind and body using bionic prosthetics and direct brain-computer interfaces called cyberware, and post-democratic societal control where corporations have more influence than governments. Nihilism, post-modernism, and film noir techniques are common elements, and the protagonists may be disaffected or reluctant anti-heroes. Noteworthy authors in this genre are William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, Pat Cadigan, and Rudy Rucker. The 1982 film Blade Runner is commonly accepted as a definitive example of the cyberpunk visual style.[27]

Time Travel

Time travel stories have antecedents in the 18th and 19th centuries, and this subgenre was popularized by H. G. Wells's novel The Time Machine. Stories of this type are complicated by logical problems such as the grandfather paradox.[28] Time travel is a popular subject in novels, television series (most famously Doctor Who), as individual episodes within more general science fiction series (for example, "The City on the Edge of Forever" in Star Trek, "Babylon Squared" in Babylon 5, and "The Banks of the Lethe" in Andromeda) and as one-off productions such as The Flipside of Dominick Hide.

Alternate history

Alternate history stories are based on the premise that historical events might have turned out differently. These stories may use time travel to change the past, or may simply set a story in a universe with a different history from our own. Classics in the genre include Bring the Jubilee by Ward Moore, in which the South wins the American Civil War and The Man in the High Castle, by Philip K. Dick, in which Germany and Japan win World War II. The Sidewise Award acknowledges the best works in this subgenre; the name is taken from Murray Leinster's early story "Sidewise in Time".

Military SF

Military science fiction is set in the context of conflict between national, interplanetary, or interstellar armed forces; the primary viewpoint characters are usually soldiers. Stories include detail about military technology, procedure, ritual, and history; military stories may use parallels with historical conflicts. Heinlein's Starship Troopers is an early example, along with the Dorsai novels of Gordon Dickson. Prominent military SF authors include David Drake, David Weber, Jerry Pournelle, S. M. Stirling, and Lois McMaster Bujold. Joe Haldeman's The Forever War is a critique of the genre, a Vietnam-era response to the World War II-style stories of earlier authors.[29] Baen Books is known for cultivating military science fiction authors.[30] Television series within this subgenre include Battlestar Galactica, Stargate SG-1 and Space: Above and Beyond. The popular Halo videogame and novel series is another prominent modern example.

Other SF Genres

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Related genres

Speculative fiction, fantasy, and horror

The broader category of speculative fiction[31] includes science fiction, fantasy, alternate histories (which may have no particular scientific or futuristic component), and even literary stories that contain fantastic elements, such as the work of Jorge Luis Borges or John Barth. For some editors, magic realism is considered to be within the broad definition of speculative fiction.[32]

Fantasy

Fantasy is closely associated with science fiction, and many writers, including Robert A. Heinlein, Poul Anderson, Larry Niven, C. J. Cherryh, C.S. Lewis, Jack Vance, and Lois McMaster Bujold have worked in both genres, while writers such as Anne McCaffrey and Marion Zimmer Bradley have written works that appear to blur the boundary between the two related genres.[33] The authors' professional organization is called the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA).[34] SF conventions routinely have programming on fantasy topics,[35][36][37] and fantasy authors such as J. K. Rowling and J. R. R. Tolkien (in film adaptation) have won the highest honor within the science fiction field, the Hugo Award.[38] Some works show how difficult it is to draw clear boundaries between subgenres, for example Larry Niven's The Magic Goes Away stories treat magic as just another force of nature and subject to natural laws which resemble and partially overlap those of physics.

However, most authors and readers make a distinction between fantasy and SF. In general, science fiction is the literature of things that might someday be possible, and fantasy is the literature of things that are inherently impossible.[9] Magic and mythology are popular themes in fantasy.[39]

It is common to see narratives described as being essentially science fiction but "with fantasy elements." The term "science fantasy" is sometimes used to describe such material.[40]

Horror fiction

Horror fiction is the literature of the unnatural and supernatural, with the aim of unsettling or frightening the reader, sometimes with graphic violence. Historically it has also been known as "weird fiction." Although horror is not per se a branch of science fiction, many works of horror literature incorporates science fictional elements. One of the defining classical works of horror, Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein, is a fully-realized work of science fiction, where the manufacture of the monster is given a rigorous science-fictional grounding. The works of Edgar Allan Poe also helped define both the science fiction and the horror genres.[41] Today horror is one of the most popular categories of films.[42]

Mystery fiction

Works in which science and technology are a dominant theme, but based on current reality, may be considered mainstream fiction. Much of the thriller genre would be included, such as the novels of Tom Clancy or Michael Crichton, or the James Bond films.[43]

Modernist works from writers like Kurt Vonnegut, Philip K. Dick, and Stanisław Lem have focused on speculative or existential perspectives on contemporary reality and are on the borderline between SF and the mainstream.[44]

According to Robert J. Sawyer, "Science fiction and mystery have a great deal in common. Both prize the intellectual process of puzzle solving, and both require stories to be plausible and hinge on the way things really do work."[45] Isaac Asimov, Anthony Boucher, Walter Mosley, and other writers incorporate mystery elements in their science fiction, and vice versa.

Superhero fiction

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

History

As a means of understanding the world through speculation and storytelling, science fiction has antecedents back to mythology, though precursors to science fiction as literature began to emerge from the 13th century (Ibn al-Nafis, Theologus Autodidactus)[46] to the 17th century (the real Cyrano de Bergerac with "Voyage de la Terre à la Lune" and "Des états de la Lune et du Soleil") and the Age of Reason with the development of science itself, Voltaire's Micromégas was one of the first, together with Jonathan Swift's "Gulliver's travels.[47] Following the 18th century development of the novel as a literary form, in the early 19th century, Mary Shelley's books Frankenstein and The Last Man helped define the form of the science fiction novel;[48] later Edgar Allan Poe wrote a story about a flight to the moon.[49] More examples appeared throughout the 19th century. Then with the dawn of new technologies such as electricity, the telegraph, and new forms of powered transportation, writers like Jules Verne and H. G. Wells created a body of work that became popular across broad cross-sections of society.[50] In the late 19th century the term "scientific romance" was used in Britain to describe much of this fiction, and would continue to be used into the early 20th century for writers such as Olaf Stapledon.

In the early 20th century, pulp magazines helped develop a new generation of mainly American SF writers, influenced by Hugo Gernsback, the founder of Amazing Stories magazine.[23] In the late 1930s, John W. Campbell became editor of Astounding Science Fiction, and a critical mass of new writers emerged in New York City in a group called the Futurians, including Isaac Asimov, Damon Knight, Donald A. Wollheim, Frederik Pohl, James Blish, Judith Merril, and others.[51] Other important writers during this period included Robert A. Heinlein, Arthur C. Clarke, and A. E. Van Vogt. Campbell's tenure at Astounding is considered to be the beginning of the Golden Age of science fiction, characterized by hard SF stories celebrating scientific achievement and progress.[23] This lasted until postwar technological advances, new magazines like Galaxy under Pohl as editor, and a new generation of writers began writing stories outside the Campbell mode.

In the 1950s, the Beat generation included speculative writers like William S. Burroughs. In the 1960s and early 1970s, writers like Frank Herbert, Samuel R. Delany, Roger Zelazny, and Harlan Ellison explored new trends, ideas, and writing styles, while a group of writers, mainly in Britain, became known as the New Wave.[47] In the 1970s, writers like Larry Niven and Poul Anderson began to redefine hard SF.[52] Ursula K. Le Guin and others pioneered soft science fiction.[53]

In the 1980s, cyberpunk authors like William Gibson turned away from the traditional optimism and support for progress of traditional science fiction.[54] Star Wars helped spark a new interest in space opera,[55] focusing more on story and character than on scientific accuracy. C. J. Cherryh's detailed explorations of alien life and complex scientific challenges influenced a generation of writers.[56]

Emerging themes in the 1990s included environmental issues, the implications of the global Internet and the expanding information universe, questions about biotechnology and nanotechnology, as well as a post-Cold War interest in post-scarcity societies; Neal Stephenson's The Diamond Age comprehensively explores these themes. Lois McMaster Bujold's Vorkosigan novels brought the character-driven story back into prominence.[57] The television series Star Trek: The Next Generation began a torrent of new SF shows,[58] of which Babylon 5 was among the most highly acclaimed in the decade.[59][60] A general concern about the rapid pace of technological change crystallized around the concept of the technological singularity, popularized by Vernor Vinge's novel Marooned in Realtime and then taken up by other authors. Television shows like Buffy the Vampire Slayer and films like The Lord of the Rings created new interest in all the speculative genres in films, television, computer games, and books. According to Alan Laughlin, the Harry Potter stories have been wildly popular among young readers, increasing literacy rates worldwide.[61]

Innovation

While SF has provided criticism of developing and future technologies, it also produces innovation and new technology. The discussion of this topic has occurred more in literary and sociological than in scientific forums.

Cinema and media theorist Vivian Sobchack examines the dialogue between science fiction film and the technological imagination. Technology does impact how artists portray their fictionalized subjects, but the fictional world gives back to science by broadening imagination. While more prevalent in the beginning years of science fiction with writers like Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, Frank Walker and Arthur C. Clarke, new authors like Michael Crichton still find ways to make the currently impossible technologies seem so close to being realized.[62]

This has also been notably documented in the field of nanotechnology with University of Ottawa Professor José Lopez's article "Bridging the Gaps: Science Fiction in Nanotechnology." Lopez links both theoretical premises of science fiction worlds and the operation of nanotechnologies. [63]

Literature

References to the most noteworthy science fiction books and authors are included here.

Authors

External link: Locus 1977 All-Time Best Author Poll

Novels and shorter literary forms

- List of science fiction novels

- Hugo Award for Best Novel

- List of science fiction short stories

- Hugo Award for Best Novella

- Hugo Award for Best Novellette

- Hugo Award for Best Short Story

Non-fiction, anthologies, and magazines

- Hugo Award for Best Non-Fiction Book

- Hugo Award for Best Related Book

- Category:Science fiction magazines

Critical Assessments and Reading Lists

- Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America - their "Suggested Reading" page

- The Complete Review - reviews of select speculative-fiction authors and works

- The Scriptorium - reviews of eminent speculative-fiction authors

- Classics of Science Fiction - lists, with various breakdowns

Fandom and community

Science fiction fandom is the "community of the literature of ideas... the culture in which new ideas emerge and grow before being released into society at large."[64] Members of this community, "fans", are in contact with each other at conventions or clubs, through print or online fanzines, or on the Internet using web sites, mailing lists, and other resources.

SF fandom emerged from the letters column in Amazing Stories magazine. Soon fans began writing letters to each other, and then grouping their comments together in informal publications that became known as fanzines.[65] Once they were in regular contact, fans wanted to meet each other, and they organized local clubs. In the 1930s, the first science fiction conventions gathered fans from a wider area.[66] Conventions, clubs, and fanzines were the dominant form of fan activity, or "fanac", for decades, until the Internet facilitated communication among a much larger population of interested people.

Awards

Among the most respected awards for science fiction are the Hugo Award, presented by the World Science Fiction Society at Worldcon, and the Nebula Award, presented by SFWA and voted on by the community of authors. One notable award for science fiction films is the Saturn Award. It is presented annually by the The Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror Films.

There are national awards, like Canada's Aurora Award, regional awards, like the Endeavour Award presented at Orycon for works from the Pacific Northwest, special interest or subgenre awards like the Chesley Award for art or the World Fantasy Award for fantasy. Magazines may organize reader polls, notably the Locus Award.

Conventions, clubs, and organizations

Conventions (in fandom, shortened as "cons"), are held in cities around the world, catering to a local, regional, national, or international membership. General-interest conventions cover all aspects of science fiction, while others focus on a particular interest like media fandom, filking, etc. Most are organized by volunteers in non-profit groups, though most media-oriented events are organized by commercial promoters. The convention's activities are called the "program", which may include panel discussions, readings, autograph sessions, costume masquerades, and other events. Activities that occur throughout the convention are not part of the program; these commonly include a dealer's room, art show, and hospitality lounge (or "con suites").[67] Conventions may host award ceremonies; Worldcons present the Hugo Awards each year. SF societies, referred to as "clubs" except in formal contexts, form a year-round base of activities for science fiction fans. They may be associated with an ongoing science fiction convention, or have regular club meetings, or both. Most groups meet in libraries, schools and universities, community centers, pubs or restaurants, or the homes of individual members. Long-established groups like the New England Science Fiction Association and the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society have clubhouses for meetings and storage of convention supplies and research materials.[68]

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA) was founded by Damon Knight in 1965 as a non-profit organization to serve the community of professional science fiction authors.[34]

Fandom has helped incubate related groups, including media fandom,[69] the Society for Creative Anachronism,[70] gaming,[71] filking, and furry fandom[72].

Fanzines and online fandom

The first science fiction fanzine, "The Comet", was published in 1930.[73] Fanzine printing methods have changed over the decades, from the hectograph, the mimeograph, and the ditto machine, to modern photocopying. Subscription volumes rarely justify the cost of commercial printing. Modern fanzines are printed on computer printers or at local copy shops, or they may only be sent as email.

The best known fanzine (or "'zine") today is Ansible, edited by David Langford, winner of numerous Hugo awards. Other fanzines to win awards in recent years include File 770, Mimosa, and Plotka.[74]

Artists working for fanzines have risen to prominence in the field, including Brad W. Foster, Teddy Harvia and Joe Mayhew; the Hugos include a category for Best Fan Artists.[74]

The earliest organized fandom online was the SF Lovers community, originally a mailing list in the late 1970s with a text archive file that was updated regularly.[75] In the 1980s, Usenet groups greatly expanded the circle of fans online. In the 1990s, the development of the World-Wide Web exploded the community of online fandom by orders of magnitude, with thousands and then literally millions of web sites devoted to science fiction and related genres for all media.[68] Most such sites are small, ephemeral, and/or very narrowly focused, though sites like SF Site offer a broad range of references and reviews about science fiction.

Fan fiction

Fan fiction, known to aficionados as "fanfic", is non-commercial fiction created by fans in the setting of an established book, film, or television series.[76]

This modern meaning of the term should not be confused with the traditional (pre-1970s) meaning of "fan fiction" within the community of fandom, where the term meant original or parody fiction written by fans and published in fanzines, often with members of fandom as characters therein ("faan fiction"). Examples of this would include the Goon stories by Walt Willis.

In the last few years, sites have appeared such as Orion's Arm and Galaxiki, which encourage collaborative development of science fiction universes.

See also

- List of science fiction themes

- SF Site

- UK science fiction and fantasy magazine SFX

- Digital library projects: science fiction

- Skiffy

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ N. E. Lilly (2002-03). "What is Speculative Fiction?". Retrieved 2007-01-16.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Del Rey, Lester (1979). The World of Science Fiction: 1926-1976. Ballantine Books. p. 5. ISBN 0-345-25452-x.

- ^ Card, Orson Scott (1990). How to Write Science Fiction and Fantasy. Writer's Digest Books. p. 17. ISBN 0-89879-416-1.

- ^ Hartwell, David G. (1996). Age of Wonders: Exploring the World of Science Fiction. Tor Books. pp. 109–131. ISBN 0-312-86235-0.

- ^ Marg Gilks, Paula Fleming and Moira Allen (2003). "Science Fiction: The Literature of Ideas". WritingWorld.com.

- ^

Knight, Damon Francis (1967). In Search of Wonder: Essays on Modern Science Fiction. Advent Publishing, Inc. pp. pg xiii. ISBN 0911682317.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Nabokov, Vladimir Vladimirovich (1973). Strong opinions. McGraw-Hill. pp. pg. 3 et seq. ISBN 0070457379.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Heinlein, Robert A. (1959). "Science Fiction: Its Nature, Faults and Virtues". The Science Fiction Novel: Imagination and Social Criticism. University of Chicago: Advent Publishers.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Rod Serling (1962-03-09). The Twilight Zone, "The Fugitive".

- ^ Del Rey, Lester (1980). The World of Science Fiction 1926-1976. Garland Publishing.

- ^ The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2000.

- ^ "www.jessesword.com/sf/view/210". Retrieved 2007-02-02.

- ^ Whittier, Terry (1987). Neo-Fan's Guidebook.

- ^ Scalzi, John (2005). The Rough Guide to Sci-Fi Movies.

- ^ Ellison, Harlan (1998). ""Harlan Ellison's responses to online fan questions at ParCon"". Retrieved 2006-04-25.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ John Clute and Peter Nicholls, ed. (1993). ""Sci fi" (article by Peter Nicholls)". Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Orbit/Time Warner Book Group UK.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ John Clute and Peter Nicholls, ed. (1993). ""SF" (article by Peter Nicholls)". Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Orbit/Time Warner Book Group UK.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Ansible". David Langford.

- ^ "An Interview with Hal Duncan". Del Rey Online. 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- ^ "Arthur C. Clarke, 1917-". Pegasos. 2000. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- ^ Chester, Tony (2002-03-17). "A Fall of Moondust". Concatenation. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- ^ a b c Agatha Taormina (2005-01-19). "A History of Science Fiction". Northern Virginia Community College. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- ^ Hartwell, David G. (1996-08). Age of Wonders. Tor Books. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Maas, Wendy (2004-07). Ray Bradbury: Master of Science Fiction and Fantasy. Enslow Publishers.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ It was later refined by William Gibson's book, Neuromancer which is credited for envisioning cyberspace. Published in the November 1983 issue of Amazing Science Fiction Stories; Bethke, Bruce. "Cyberpunk". Infinity Plus. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ James O'Ehley (1997-07). "SCI-FI MOVIE PAGE PICK: BLADE RUNNER - THE DIRECTOR'S CUT". Sci-Fi Movie Page. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Time Travel and Modern Physics". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2000-02-17. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Henry Jenkins (1999=07-23). "Joe Haldeman, 1943-". Retrieved 2007-01-16.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Website Interview with Toni Weisskopf on SF Canada". Baen Books. 2005-09-12. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- ^ "Science Fiction Citations". Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- ^ "Aeon Magazine Writer's Guidelines". 2006-04-26. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

{{cite web}}: Text "publisher+Aeon Magazine" ignored (help) - ^ "Anne McCaffrey". tor.com. 1999-08-16. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ^ a b "Information About SFWA". Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, Inc. Retrieved 2006-01-16.

- ^ Peggy Rae Sapienza and Judy Kindell (2006-03-23). "Student Science Fiction and Fantasy Contest". L.A.con IV. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- ^ Steven H Silver (2000-09-39). "Program notes". Chicon 2000. Retrieved 2001-01-16.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Carol Berg. "Links, "Conventions and Writers' Workshops"". Retrieved 2001-01-16.

- ^ "The Hugo Awards By Category". World Science Fiction Society. 2006-07-26. Retrieved 2006-01-16.

- ^ Robert B. Marks (1997-05). "On Incorporating Mythology into Fantasy, or How to Write Mythical Fantasy in 752 Easy Steps". Story and Myth. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Elkins, Charles (1980-11). "Recent Bibliographies of Science Fiction and Fantasy". Science Fiction Studies. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ David Carroll and Kyla Ward (1993-05). "The Horror Timeline, "Part I: Pre-20th Century"". Burnt Toast (#13). Retrieved 2001-01-16.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Chad Austin. "Horror Films Still Scaring – and Delighting – Audiences". North Carolina State University News. Retrieved 2006-01-16.

- ^ "Utopian ideas hidden inside Dystopian sf". False Positives. 2006-11. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Glenn, Joshua (2000-12-22). "Philip K. Dick (1928-1982)". Hermenaut (#13). Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- ^ McBride, Jim (1997-11). "Spotlight On... Robert J. Sawyer". Fingerprints (November 1997). Crime Writes of Canada. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Dr. Abu Shadi Al-Roubi (1982), "Ibn al-Nafis as a philosopher", Symposium on Ibn al-Nafis, Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait (cf. Ibnul-Nafees As a Philosopher, Encyclopedia of Islamic World).

- ^ a b "Science Fiction". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ John Clute and Peter Nicholls (1993). "Mary W. Shelley". Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Orbit/Time Warner Book Group UK. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ Poe, Edgar Allan. The Works of Edgar Allan Poe, Volume 1, "The Unparalleled Adventures of One Hans Pfaal". Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ "Science Fiction". Encarta® Online Encyclopedia. Microsoft. 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ Resnick, Mike (1997). "The Literature of Fandom". Mimosa (#21). Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ "SF TIMELINE 1960-1970". Magic Dragon Multimedia. 2003-12-24. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ Browning, Tonya (1993). "A brief historical survey of women writers of science fiction". University of Texas in Austin. Retrieved 2007-01-19.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Philip Hayward (1993). Future Visions: New Technologies of the Screen. British Film Institute. pp. 180–204. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ Allen Varney (2004-01-04). "Exploding Worlds!". Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ Vera Nazarian (2005-05-21). "Intriguing Links to Fabulous People and Places..." Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ "Shards of Honor". NESFA Press. 2004-05-10. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ Scott Cummings (2006-09-21). "Star Trek: The Next Generation". Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ David Richardson (1997-07). "Dead Man Walking". Cult Times. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Nazarro, Joe. "The Dream Given Form". TV Zone Special (#30).

- ^ Linda Doherty (2002-09-19). "Harry Potter helps lift school literacy rates". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- ^ Sheila Schwartz (1971). "Science Fiction: Bridge between the Two Cultures". The English Journal. Retrieved 03-26-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Jose Lopez (2004). "Bridging the Gaps: Science Fiction in Nanotechnology". Hyle. Retrieved 03-23-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ von Thorn, Alexander (2002-08). "Aurora Award acceptance speech". Calgary, Alberta.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Wertham, Fredric (1973). The World of Fanzines. Carbondale & Evanston: Southern Illinois University Press.

- ^ "Fancyclopedia I: C - Cosmic Circle". fanac.org. 1999-08-12. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ Lawrence Watt-Evans (1000-03-15). "What Are Science Fiction Conventions Like?". Retrieved 2007-01-17.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Mike Glyer (1998-11). "Is Your Club Dead Yet?". File 770. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Text "issue-127" ignored (help) - ^ Robert Runte (2003). "History of sf Fandom". Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ "Origins of the Middle Kingdom". Folump Enterprises. 1994. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ Ken St. Andre (2006-02-03). "History". Central Arizona Science Fiction Society. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ Patten, Fred (2006). Furry! The World's Best Anthropomorphic Fiction. ibooks.

- ^ Rob Hansen (2003-08-13). "British Fanzine Bibliography". Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ a b "Hugo Awards by Category". World Science Fiction Society. 2006-07-26. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ Keith Lynch (1994-07-14). "History of the Net is Important". Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2003. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

References

- Barron, Neil, ed. Anatomy of Wonder: A Critical Guide to Science Fiction (5th ed.). (Libraries Unlimited, 2004) ISBN 1-59158-171-0.

- Clute, John Science Fiction: The Illustrated Encyclopedia. London: Dorling Kindersley, 1995. ISBN 0-7513-0202-3.

- Clute, John and Peter Nicholls, eds., The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. St Albans, Herts, UK: Granada Publishing, 1979. ISBN 0-586-05380-8.

- Clute, John and Peter Nicholls, eds., The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin's Press, 1995. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- Disch, Thomas M. The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of. Touchstone, 1998.

- Reginald, Robert. Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature, 1975-1991. Detroit, MI/Washington, DC/London: Gale Research, 1992. ISBN 0-8103-1825-3.

- Weldes, Jutta, ed. To Seek Out New Worlds: Exploring Links between Science Fiction and World Politics. Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. ISBN 0-312-29557-X.

- Westfahl, Gary, ed. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders (three volumes). Greenwood Press, 2005.

- Wolfe, Gary K. Critical Terms for Science Fiction and Fantasy: A Glossary and Guide to Scholarship. Greenwood Press, 1986. ISBN 0-313-22981-3.

External links

- SF Hub - resources for science-fiction research

- Locus Online - Extensive reference site covering a broad range of science fiction literature, awards, and activities.

- The SF Page at Project Gutenberg of Australia

- The SF Bookshelf at Project Gutenberg (USA)

- SFRA - The Science Fiction Research Association

- Science fiction fanzines (current and historical) online

- List of science fiction and fantasy E-zines