Juan Ramón Jiménez

Juan Ramón Jiménez (born December 24, 1881 in Moguer , Andalusia , † May 29, 1958 in San Juan , Puerto Rico ) was a Spanish poet who initiated the renewal of Spanish poetry in the 20th century and the influences of modernism in his work by Rubén Darío , the late romantic emotional world of Rosalía de Castro and Gustavo Adolfo Becquer and the popular tradition of the Romancero. He was the pioneer of the Generación del 27 , to which poets such as Federico García Lorca , Rafael Alberti , Jorge Guillén and others. a. belong. Juan Ramón Jiménez received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1956 .

Life

Childhood and Adolescence (1881–1900)

Juan Ramón - as he is also called in Spanish literary studies - was born in Moguer (in the province of Huelva) on the Atlantic coast of Andalusia. His father Victor Jiménez de Nestares, a wealthy owner of vineyards and merchant ships, came from the Rioja in northern Spain, his mother Pura de Casa-Mantecón belonged to an Andalusian noble family from Osuna ( Seville ). Juan Ramón attended the exquisite Jesuit boarding school in El Puerto de Santa María near Cádiz , where he received a humanistic-classical education with the Spanish masters of the 17th century. Century became familiar and discovered French literature. In 1896 he moved to Seville as a student to study law at his father's request, but spent his time in the library of the Ateneo de Sevilla reading and writing. His readings included romantics like Musset , Heine , Byron and symbolists like Moréas or Maeterlinck , but also the Spanish late romanticists Rosalía de Castro and Becquer.

He published his first verses in local newspapers in Seville, but soon his poems appeared in the Madrid magazine Vida Nueva , which took on the young writers and wrote the modernism represented by Rubén Darío on its banner. Juan Ramón was a staunch modernist in this first creative period, although he had hardly read anything by the poet from Nicaragua, who was celebrated in Madrid . He made up for this when, in the spring of 1900, at the invitation of his poet friend Francisco Villaespesa , he traveled to Madrid for the first time to meet the master and submit his poems to him. Darío wrote a foreword for the budding poet's first collection of poems and also gave it the title Almas de violeta . Ramón del Valle-Inclán , the other great figure in the Madrid literary scene at the time, christened the second volume of verse Juan Ramóns Ninfeas . Both volumes were published in 1900. This first success was however undone by the sudden death of the father in Moguer, where the son spent the summer with the family. The stroke of fate plunged the young poet into a deep depression, which in the spring of 1901 led him to Castel d'Andorte, at the foot of the Pyrenees , to the private clinic of the French doctor Lalanne. There he spent half a year working intensively on his poems and discovering Mallarmé and Verlaine for themselves.

Early creative period

Far from recovered, he returned to Madrid at the end of 1901 and fled to the El Retiro sanatorium , where he pursued his poetry and held a small literary salon . In 1902 he published the volume of poems by Rimas , which was well received by critics and younger writers. They included the brothers Antonio and Manuel Machado , who were also regular visitors to the salon in the sanatorium. From this circle around Juan Ramón arose the magazine Helios - "one of the best of this era" -, among its collaborators Valle Inclán, Rubén Darío, Azorín , Unamuno , the Machado brothers, the painters Santiago Rusiñol and Emilio Sala as well as the novelist Juan Valera counted. The Arias tristes , published in 1903, represent a first high point in Juan Ramón's first creative period. He returned to Moguer in 1905, tired of city life and plagued by his hypochondria . There he had to witness the dissolution of his father's business and the financial decline of the family. Busy with suicidal thoughts, he found a hold in familiar nature and in his poetic work.

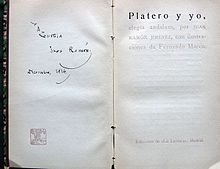

In this atmosphere of merging with nature, the lyrical prose by Platero y yo was created in 1907 , probably the most famous work of the poet, which appeared in a small edition in 1914 and in an expanded version in 1917 and which is an "Andalusian elegy" about a little donkey and its master in the poet's birthplace. The volumes of poetry Elegías puras (1908), Baladas de primavera (1910), La soledad sonora (1911), Melancolía (1912) were created, which made the thirty-year-old a recognized master. At the invitation of the Residencia de Estudiantes , Juan Ramón moved back to Madrid in 1912. The poet spent the years leading up to his marriage in 1916 to Zenobia Camprubí (1887–1956), the daughter of a Spanish engineer with family connections in the United States, in this progressive-minded educational establishment, which welcomed students from Madrid universities as well as researchers, artists and writers and a Spaniard who has been rooted in Puerto Rico for generations. Zenobia was open-minded, well-read and independent through her family and upbringing. The marriage of the lonely and melancholy poet and the cheerful young woman took place on March 2nd, 1916 in New York and was a surprise for everyone.

Diary of a newlywed poet (1916–1936)

The couple settled in Madrid, and a happy period began for the poet, when his work shed modernist pomp and began to move towards the poesía pura of his mature style. Diario de un poeta recién casado (1917), Eternidades (1918) and Piedra y cielo (1919) are milestones on this path. In the 1920s, Juan Ramón became the central figure in Spanish literary life, recognized by his peers and adored by the young. He published his Segunda antología poética (1922), in which he made a strict selection from his poems published between 1898 and 1918. The mature master applied the same artistic uncompromising attitude to his assessment of the works of others. This earned him a reputation for intolerance and pride. The then young Luis Cernuda even speaks of a "true dictatorship" by Juan Ramón in the years 1917 to 1930.

Poet in exile (1936–1958)

The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War on July 18, 1936 brought these literary skirmishes to an abrupt end. Juan Ramón and Zenobia left Madrid in August. The President of the Spanish Republic, Manuel Azaña , offered the poet the post of ambassador, but the latter was satisfied with a diplomatic passport. The couple traveled to the United States via France, where they briefly stopped in Washington, then traveled to Cuba via Puerto Rico. Juan Ramón was received and venerated everywhere as a representative of the Spanish Republic, and he also appeared publicly as a representative of the Republic. When Zenobia and Juan Ramón left Havana for Florida (USA) in 1939, the Spanish Civil War was over and Juan Ramón Jiménez was a poet in exile, without a home and without a passport. There is no doubt about the republican sentiment and loyalty of Juan Ramón, of which the book Guerra en España (1936–1953), published posthumously in 1985 and planned by him, gives eloquent testimony. The Hispanic American Institute at the University of Miami invited the poet as a visiting professor, and he spent three years lecturing, lecturing, and creative there. The Romances de Coral Gables (publ. 1948) were created between 1939 and 1942, and the prose pieces Españoles de tres mundos (1942), a series of concise contemporary portraits , were published in Argentina . After the USA entered World War II (December 1941), Juan Ramón and Zenobia moved to Washington, where both worked at the University of Maryland. The exile weighed heavily on the poet and the old depressions returned. A trip to Argentina in 1948, at the invitation of the Anales de Buenos Aires Society, was a triumphal procession for Juan Ramón, who celebrated in Buenos Aires by his old friends around the magazine Sur such as Victoria Ocampo and Borges and by Spanish exiles such as Alberti or Ramón Pérez de Ayala has been. Juan Ramón gave four lectures in Buenos Aires, but also traveled to Córdoba, Rosario, La Plata, Santa Fé and Paraná, where he spoke about Poesía y vida ('Life and Poetry'). In an interview for a Buenos Aires newspaper, he was asked why he was not returning to Spain. “Because I want to live in freedom,” was his answer. The poet's deep urge for closer proximity to the Spanish-speaking world led the couple to move to the island of Puerto Rico in 1951, at whose university in Río Piedras the poet found a favorable setting for his work and his precarious health. The years in Puerto Rico were years of reconsideration, sifting through and ordering a life's work. Juan Ramón donated his library, manuscripts, letters and autographs to the university, while Zenobia took care of cataloging and arranging the material in the rooms made available by the university. In the spring of 1956 Zenobia fell ill with an ulcer on which she had already been operated on in 1951. She lived to see her husband receive the Nobel Prize on October 25, 1956 and died on October 28. Juan Ramón outlived his wife by two years, he died in 1958.

Works

Poetry

- Almas de violeta , (1900)

- Ninfeas , (1900)

- Rimas , (1902)

- Arias tristes , (1903)

- Jardines lejanos , (1904)

- Elegías puras , (1908)

- Elegías intermedias , (1909)

- Olvidanzas: Las hojas verdes , (1909)

- Elegías lamentables , (1910)

- Baladas de primavera , (1910)

- La soledad sonora , (1911)

- Pastorales , (1911)

- Poemas magicos y dolientes (1911)

- Melancolía , (1912)

- Laberinto , (1913)

- Estío (A punta de espina) , (1915)

- Poesías escogidas (1899–1917) , (1917)

- Sonetos espirituales , (1917)

- Diario de un poeta recién casado , (1917)

- Eternidades , (1918)

- Piedra y cielo , (1919)

- Segunda antología poética (1898–1918) , (1922)

- Belleza (en verso) , (1923)

- Unidad (ocho cuadernos) , (1925)

- Obra en marcha (Diario poético de JRJ) , (1928)

- Eternidades , (1931)

- Sucesión (ocho pliegos) , (1932)

- Poesía en prosa y verso (1902–1923) , (1932)

- Presente (veinte cuadernos) , (1934)

- I (Hojas nuevas, prosa y verso) , (1935)

- Canción , (1936)

- Belleza (en verso) , (1945)

- Voces de mi copla , (1945)

- Romances de Coral Gables (1939-1942) , (1948)

- Animal de fondo , (1949)

- Tercera antología poética (1908–1953) , (1957)

prose

- Platero y yo , short version, with illustrations by Fernando Marco, Biblioteca de la Juventud, Talleres de La Lectura, Madrid 1914

- Platero y yo , complete version, Editorial Calleja, Madrid 1917

- Política poética , (1936) (lecture)

- Españoles de tres mundos (1914–1940) , edited by Ricardo Gullón, Afrodisio Aguado, Madrid 1960

- El Zaratán , (1946), published 1957

- Guerra en España (1936–1953) , diaries, poems, notes, interviews, ed. Ángel Crespo, Seix Barral, Barcelona 1985

Translations into German

- Platero and I , translation by Doris Deinhard, Insel Bucherei No. 578, Insel, Frankfurt / Main 1953

- Platero and I , translation by Fritz Vogelgsang, Insel, Frankfurt / Main 1985, 1992

-

Platero and I , translation by Gerd Breitenbürger, Freiburg (self-published); on too

- Platero and I , LP with the setting of Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (guitar: Sonja Prunnbauer, speaker: Jo Schaarschmidt), Harmonia Mundi 1988.

- Rose from ashes , 4 poems, translation by Erwin Walter Palm, Piper, Munich 1955

- Stein und Himmel / Piedra y cielo , poems in Spanish and German, transferred from Fritz Vogelgsang, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1981

- Falter aus Licht , poems, translation by Ernst Schönwiese, Heyne, Munich 1981

- Heart, die or sing , translation by Hans Leopold Davi , Diogenes, Zurich 1987

literature

- A. Campoamor González: Bibliografía general de Juan Ramón Jiménez. Taurus, Madrid 1962.

- Luis Cernuda: Estudios sobre poesía española contemporánea. Guadarrama, Madrid 1957.

- Hugo Friedrich: The structure of modern poetry. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1960.

- Francisco Garfias: Juan Ramón Jiménez. Taurus, Madrid 1958.

- Ricardo Gullón: Conversaciones con Juan Ramón. Taurus, Madrid 1958.

- Graciela Palau de Nemes: Vida y obra de Juan Ramón Jiménez. Gredos, Madrid 1957.

- Gustav Siebenmann: Modern lyric poetry in Spain, a contribution to its style history. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1965.

Individual evidence

- ^ Graciela Palau de Nemes, Vida y obra de Juan Ramón Jiménez , Gredos, Madrid 1957, pp. 15-16

- ↑ Palau de Nemes, p. 35

- ↑ Palau de Nemes, pp. 75 ff.

- ↑ Palau de Nemes, p. 90

- ↑ Palau de Nemes, pp. 134-135

- ^ Francisco Garfias: Juan Ramón Jiménez. Taurus, Madrid 1958, p. 104 ff.

- ↑ Literaturlexikon 20. Jahrhundert , ed. Helmut Olles, Rowohlt, Reinbek, 1971, pp. 406–407.

- ↑ Luis Cernuda: Estudios sobre poesía española contemporánea. Guadarrama, Madrid 1957, pp. 121-135.

- ↑ Guerra en España , Seix Barral, Barcelona 1985, p. 282.

- ^ Garfias, p. 115

- ↑ dtv-Atlas zur Weltgeschichte , p. 187

- ^ Garfias, p. 115

- ↑ Guerra en España , p. 283

- ↑ Sala Zenobia-Juan Ramón Jiménez , Biblioteca General de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, Río Piedras

- ↑ Peter Päffgen: Platero? In: Guitar & Lute , Volume 10, Issue 6, 1988, p. 46.

Web links

- Literature by and about Juan Ramón Jiménez in the catalog of the Ibero-American Institute in Berlin

- Literature by and about Juan Ramón Jiménez in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Juan Ramón Jiménez in the German Digital Library

- Literature by and about Juan Ramón Jiménez in the catalog of the library of the Instituto Cervantes in Germany

- Nobel Prize in Literature: Juan Ramón Jiménez

- Some poems, translated by Johannes Beilharz

- Love poems by Juan Ramón Jiménez ( Memento from February 8, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Jiménez, Juan Ramón |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Jiménez Mantecón, Juan Ramón (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Spanish poet, prose writer and Nobel Prize winner |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 24, 1881 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Moguer , Andalusia |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 29, 1958 |

| Place of death | San Juan (Puerto Rico) |