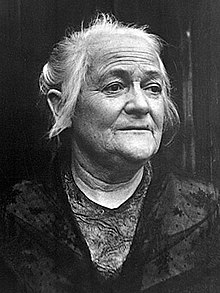

Clara Zetkin

Clara Josephine Zetkin , née Eißner (* July 5, 1857 in Wiederau , Amtshauptmannschaft Rochlitz , Kingdom of Saxony ; † June 20, 1933 in Arkhangelskoje , Moscow Oblast , Soviet Union ) was a socialist - communist German politician, peace activist and women's rights activist . She was active in the SPD until 1917 and was a prominent representative of the revolutionary- Marxist faction in this party . In 1917 she joined the SPD spin-off USPD . There they belonged to the left wing or the Spartacus group during the November Revolution in 1918 Spartacus League has been renamed. This in turn merged with other left-wing revolutionary groups in the newly founded Communist Party of Germany (KPD) at the turn of the year 1918/1919 . As an influential member of the KPD, Zetkin was a member of the Reichstag from 1920 to 1933 and age-president of parliament in 1932 .

At the supranational level, Zetkin was one of the founders of the Second International of the socialist labor movement as a participant in the International Workers' Congress in Paris in 1889 . In her work for the International , she is regarded as the formative initiator of International Women's Day . As a member of the headquarters or of the executive committee of the KPD, later known as the Central Committee , she was a member of the Executive Committee of the Communist International (EKKI) from 1921 to 1933 , where in the last years of her life she belonged to the minority of critics of the social fascism thesis ultimately prescribed by Stalin .

However, this did not mean a fundamental criticism of the Communist International and the Soviet Russian dictatorship under Stalin. Zetkin never publicly criticized the KPD's course under Thälmann, which was tantamount to "submission to the Stalinist principles". In a Moscow show trial against social revolutionary opponents of the regime in 1922, Zetkin had also acted as a prosecutor, demanded the death penalty and published a "Kampfschrift" on it in the Comintern-Verlag. When Felix Dzerzhinsky , who carried out the “ Red Terror ” as head of the Cheka secret police, died in 1926 , Zetkin praised its approach in a letter to the CPSU Central Committee as “exemplary”; Dzerzhinsky achieved “decisive and unforgettable things”, he “cleared [...] the way for socialist construction”.

Life

Origin and education

Clara was born as the eldest daughter of Josephine Vitale and Gottfried Eißner (also Eisner). Gottfried Eißner was the son of a day laborer and village school teacher in Wiederau. Josephine Vitale's father, Jean Dominique, was shaped by the French Revolution in 1789 and his participation in Napoleon's wars . Her mother was in contact with pioneers of the (bourgeois) women's movement that had emerged at the time, in particular Louise Otto-Peters and Auguste Schmidt , read books by George Sand and founded an association for women's gymnastics in Wiederau .

The family moved to Leipzig in 1872 to give their children a better education. Clara Zetkin was trained there in private seminars to become an elementary school teacher. 1879 she was in Zschopau in the family business Bodemer worked as a private tutor.

Political engagement in early social democracy and first exile

(from left to right: Dr. Ferdinand Simon (1862–1912), Friederike Simon, née Bebel (1869–1948), Clara Zetkin, Friedrich Engels , Julie Bebel , August Bebel , Ernst Schattner, Regina Bernstein, née Zadek, married Schattner (1849 / 1852–1923) and Eduard Bernstein (partially cut off))

From 1874 the elementary school teacher trained in private seminars in Leipzig had contacts with the women's and labor movement . Clara Eißner joined the Socialist Workers' Party of Germany in 1878 , which was renamed the SPD (Social Democratic Party of Germany) in 1890. Because of the Socialist Law (1878–1890), which forbade social democratic activities outside the state parliaments and the Reichstag, she went into exile in 1882, first to Zurich , then to Paris . There she took the name of her life partner, the Russian revolutionary Ossip Zetkin , with whom she had two sons, Maxim Zetkin (1883-1965) and Kostja Zetkin (1885-1980).

During her time in Paris in 1889, during the International Workers' Congress , she played an important role in founding the Socialist International .

In the fall of 1890 the family returned to Germany and settled in Sillenbuch near Stuttgart . There Clara Zetkin worked as a translator for the Dietz publishing house and since 1892 as editor-in-chief of the social democratic women's magazine Die Gleichheit .

After Ossip Zetkin's death, in 1899, at the age of 42, she married the 24-year-old painter Friedrich Zundel from Wiernsheim in Stuttgart . After growing estrangement, the marriage was divorced in 1927 and in the same year Friedrich Zundel married Paula Bosch , the daughter of his Sillenbuch neighbor Robert Bosch .

In 1907, on the occasion of the International Socialist Congress in Stuttgart, Clara Zetkin met the Russian communist Lenin , with whom she had a lifelong friendship.

In the SPD, she and her close confidante, friend and fellow campaigner, Rosa Luxemburg, were part of the revolutionary left wing of the party and, together with her, turned against the reform-oriented theses of Eduard Bernstein in the revisionism debate around the turn of the 20th century .

The women's rights activist

One of her political priorities was women's politics . To this end, she held the founding congress of the Second International on 19 July 1889 has become famous speech in which she demands of the women's movement for women's suffrage , free choice of employment and special labor laws for women as to Helene Lange and Minna Cauer were represented and within of the ruling system criticized:

“We expect our full emancipation neither from the admission of women to what is called free trade and from instruction that is the same as that of men - although the demand for these two rights is only natural and just - nor from the granting of political rights. The countries in which supposedly universal, free and direct suffrage exists show us how little it really is worth. The right to vote without economic freedom is nothing more and nothing less than a change that has no course. If social emancipation depended on political rights, no social question would exist in countries with universal suffrage. The emancipation of women like that of the whole human race will be exclusively the work of the emancipation of labor from capital. Only in a socialist society will women and workers acquire full rights. "

With this, Zetkin declared the lack of equality between the sexes to be a secondary contradiction of the prevailing social and economic conditions, which she subordinated to the main contradiction between capital and labor. Her postponement of formal political emancipation of women to the period after the revolution deepened the conflicts of the German women's movement before the First World War and led to lengthy arguments with other, more moderate protagonists, including within the social democratic women's movement, such as Lily Braun or Luise Zietz .

From 1891 to 1917 Zetkin was editor-in-chief of the SPD women's newspaper Die Equality (or its predecessor Die Arbeiterin ), in whose programmatic opening number she once again turned against the reformist notion, through legal equality with men while maintaining capitalism, a step forward for women want to achieve:

“'Equality' […] is based on the conviction that the ultimate reason for the low social position of women, which is thousands of years old, is not to be found in the legislation 'made by men', but in the property relations caused by economic conditions. Even if our entire legislation is changed today so that the female sex is legally placed on the same footing as the male, social slavery in the hardest form still remains for the great majority of women: their economic dependence on their exploiters. "

She later revised this rigid stance and now also advocated women's suffrage, which had been a central component of the SPD's party program since 1891 .

In 1907 she was appointed head of the newly established women's secretariat of the SPD. At the “ International Socialist Congress ”, which took place in Stuttgart in August 1907, the founding of the Socialist Women's International was decided - with Clara Zetkin as the international secretary. At the Second International Socialist Women's Conference in Copenhagen on August 27, 1910 , against the will of her male party colleagues, together with Käte Duncker , she initiated International Women's Day , which was to be celebrated for the first time the following year on March 19, 1911 (from 1921 on March 8, 1911). March).

During the First World War

Along with Franz Mehring , Rosa Luxembourg and other prominent SPD politicians belonged Zetkin shortly before the start of World War I in 1914 to the minority of opponents to authorization by the war credits in the bodies of his own party. It thus remained true to the principle of the Second International not to support a war of aggression and from then on stood in contradiction to the majority of the SPD represented in the Reichstag . Accordingly, from the beginning of World War I , she rejected the truce policy of her party. In December 1914 , Karl Liebknecht was the first member of the Reichstag to break with parliamentary group discipline and vote against the approval of war credits.

Among other activities against the war, Zetkin organized the International Conference of Socialist Women Against the War in Bern , the capital of neutral Switzerland , in 1915 . In this context, the anti-war leaflet "Women of the working people!", Which was largely formulated by her , was created, the distribution of which outside of Switzerland, especially in the Central Powers Austria-Hungary and the German Reich, was banned by the police. Because of her anti-war stance, Clara Zetkin was arrested several times during the war, her mail confiscated and her sons, both doctors in military service, harassed.

From the SPD to the KPD

From 1916 she was involved in the revolutionary inner-party opposition faction of the SPD, the Gruppe Internationale or Spartakusgruppe , originally founded by Rosa Luxemburg , which was renamed the Spartakusbund on November 11, 1918 . In 1917 Clara Zetkin joined the USPD - immediately after it was constituted. This new left-wing social democratic party split off from the parent party in protest against the SPD's approval of the war after the larger group of war opponents had been excluded from the SPD parliamentary group and the party. After the November Revolution - based on the Spartakusbund and other left-wing revolutionary groups - the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) was founded on January 1, 1919 , which Zetkin also joined.

From 1919 to 1920 Zetkin was a member of the state constituent assembly of Württemberg and one of the first 13 female MPs there. From July 25, 1919, she participated in the special committee for the draft of a youth welfare law. On September 25, 1919, Zetkin voted against the adoption of the constitution of the free people's state of Württemberg .

From 1920 to 1933 she was a member of the KPD in the Reichstag of the Weimar Republic . From 1919 Clara Zetkin published the magazine Die Kommunistin . From 1921 until her death she was President of the International Workers Aid (IAH) . In the KPD, Zetkin was a member of the headquarters until 1924, and from 1927 to 1929 of the party's central committee . She was also a member of the Executive Committee of the Communist International (EKKI) from 1921 to 1933 .

In 1925, Zetkin was also elected chairman of the Red Aid in Germany .

In the KPD, Zetkin sat in the course of her political activity, during which the dominant inner-party wing changed several times, often between the chairs, but retained significant influence in the party throughout her life. In general, well-known historians such as Heinrich August Winkler assign it to the “right” wing of the KPD, mainly because, despite its membership in the EKKI, it was sometimes critical of the ideological guidelines of the Comintern and the Soviet Union .

For example, in 1921 - after the unification of the KPD with the large left wing of the USPD to form the party that temporarily operated under the alternative abbreviation VKPD - together with the KPD chairman Paul Levi, who was then in office from March 1919 to February 1921, who was controversial within the party (expulsion from the party in mid-1921) Comintern leader Grigory Yevsejewitsch Zinoviev advocated "offensive strategy" as "putschism". In the corresponding campaign, which was largely supported by the KPD, a revolutionary workers' revolt, the March Action in the province of Saxony , failed bloody, killing over a hundred people. Unlike the party leaders Levi and Ernst Däumig , however, she stayed in the KPD and did not join the Communist Working Group (KAG).

On January 21, 1923 shortly after the beginning of the occupation of the Ruhr by French and Belgian troops as a result of of Germany failure to reparation under the terms of the Versailles Treaty of 1919, threw Zetkin under the heading To the fatherland of the big bourgeoisie before their "betrayal “Is to blame for the critical worsening of the situation in the Weimar Republic as a result of hyperinflation and reparations . With the leaflet "For the Liberation of the German Fatherland", she called for the overthrow of the Cuno government and the formation of a workers' government . These seemingly nationalistic tones, which briefly led to Zetkin being accused by some party members of trying to overtake the bourgeois parties with national slogans, were corrected two days later by the party headquarters. With the slogan "Hit Poincaré on the Ruhr and Cuno on the Spree", the KPD called for solidarity among the proletarians in Germany and France, thereby reinforcing the KPD's internationalist orientation.

In June 1923, Zetkin caused a sensation at the meeting of the Executive Committee of the Comintern in Moscow with her theses on the class character of fascism , which had come to power in Italy the previous year. The thesis widespread among many Marxists that Mussolini's dictatorship is to be understood as “mere bourgeois terror” and as the fearful reaction of the capitalists to the threat posed by the October Revolution was sharply rejected. In truth, fascism ...

"[...] another root. It is the stagnation, the slow pace of the world revolution as a result of the betrayal of the reformist leaders of the labor movement. A large part of the proletarianized and threatened by proletarianization of the lower and middle bourgeois classes, civil servants and bourgeois intellectuals had replaced war psychology with a certain sympathy for reformist socialism. They hoped that reformist socialism would turn the world around thanks to 'democracy'. These expectations have been bitterly disappointed. [...] So it happened that they not only lost faith in the reformist leaders, but in socialism itself. "

She described National Socialism as a “punishment” for the behavior of the German Social Democrats in the November Revolution.

In April 1925, Zetkin polemicized at another EKKI conference in Moscow against the then current KPD leadership under Ruth Fischer and Arkadi Maslow , whom she accused of “sectarian politics”. In doing so, she helped prepare for their removal. He was succeeded in autumn 1925 by Ernst Thälmann , who was a protector of Stalin .

Zetkin described the parliamentary democracy of the Weimar Republic as the "class dictatorship of the bourgeoisie" and strictly rejected it. At the same time, however, she was also critical of the Stalinist social fascism thesis , which prevented an alliance with social democracy against National Socialism. As senior president of the German Reichstag, she chaired the constituent session of the Reichstag on August 30, 1932 "in the hope, despite my current disability, to experience the happiness of opening the first council congress of Soviet Germany as senior president ." Despite the previous election success for the KPD Nevertheless, she recognized the danger emanating from the now strongest parliamentary group in the Reichstag, the NSDAP , and in the same speech called for resistance to the National Socialists:

"Before this imperative historical necessity, all captivating and divisive political, union, religious and ideological attitudes must step back."

Another exile and death

After the seizure of power by the Nazi Party under Adolf Hitler and the exclusion of the Communist Party of the Diet following the Reichstag Fire in 1933 Clara Zetkin went once, the last time in their lives, into exile, this time in the Soviet Union, where they already 1924-1929 their Had had their main residence. According to Maria Reese , a KPD member of the Reichstag, who visited her there with difficulty, she was already living in isolation from party politics. She died a little later on June 20, 1933 at the age of almost 76. Her urn was buried in the necropolis on the Kremlin wall in Moscow on the right in grave number 44. Stalin himself carried the urn to the burial.

Honors

Clara Zetkin was awarded the Order of the Red Banner in 1927 and the Order of Lenin in 1932 .

Zetkin became one of the historical leading figures of the SED propaganda, in which her role as a women's rights activist and ally of the Soviet Union was emphasized. The Democratic Women's Federation of Germany dedicated a flag with an honorary banner to Clara Zetkin for the XI Federal Congress.

- The GDR set up a museum about her life in the house in Birkenwerder north of Berlin , where she had lived from 1929 to 1932, which still exists today.

- From 1971 onwards, the GDR's 10-mark notes showed their likeness.

- An important cultural site of the Stuttgart labor movement, the Waldheim Sillenbuch , bears the name Clara-Zetkin-Haus .

- The parliamentary group hall of the left parliamentary group in the Bundestag was named after her.

- Streets and schools bear their names. In Berlin, from 1951 to 1995, the parallel street to Unter den Linden that led to the Reichstag building was named after her and was then renamed back to Dorotheenstraße .

- The Clara-Zetkin-Park in Leipzig bore her name from 1955. Since 2011 only the former Albertpark and the Volkspark in Scheibenholz have been called Clara-Zetkin-Park. The remaining parts were given their old names Johannapark , Klingerhain , Palmengarten and Richard-Wagner-Hain .

- In 1987 a residential green area in the Marzahn district in Clara-Zetkin-Park was named for the 750th anniversary of the city .

- In 1997 the district office of Marzahn-Hellersdorf gave a newly designed square the name Clara-Zetkin-Platz .

- In her place of birth, Wiederau , where she lived with her parents until she was 15, there is a memorial in the former school in the museum in the old village school .

- The IG Metall women in Heidenheim have been awarding a Clara Zetkin Prize every two years since 2007, on March 8th, International Women's Day , to a woman who has made a "sustainable contribution to women's work" (e.g. . 2009 to Andrea Ypsilanti ).

- Since 2011, the Die Linke party has been awarding a Clara Zetkin Women's Prize , endowed with 3,000 euros , “to honor outstanding achievements by women in society and politics” (first winner: Florence Hervé ).

- On the occasion of International Women's Day 2012, Gregor Gysi suggested to Bundestag President Norbert Lammert that the new Bundestag building at Wilhelmstrasse 65 be named after Clara Zetkin, but this did not happen.

- Clara Zetkin Memorials and Monuments (selection)

Clara Zetkin monument in the Berlin park of the same name

Clara Zetkin memorial in Birkenwerder

Clara Zetkin Monument in Dresden

Clara Zetkin memorial in the Johannapark in Leipzig

Clara Zetkin Monument in Neubrandenburg

- Clara Zetkin as a motif for postage stamps and means of payment of the GDR a. a. States of the former "Eastern Bloc"

Publications of works by Zetkin (selection)

- The Workers' Question of the Present. Verlag der Berliner Volks-Tribüne, Berlin 1889, fes.de (PDF) Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung .

- The student and the woman. Publishing house of the socialist monthly books, Berlin 1899 The student and the woman. ( DjVu , Commons ).

- The school question. Lecture given at the third women's conference in Bremen . Expedition of the Vorwärts bookstore, Berlin 1904. Digitized at HUB Berlin

- On the question of women's suffrage. Edited after the presentation at the Conference of Socialist Women in Mannheim. Buchhandlung Vorwärts, Berlin 1907 digitized and full text in the German text archive , on the question of women's suffrage. (PDF) Friedrich Ebert Foundation .

- The right to vote for women [reason for the resolution: The right to vote for women]. In: Internationaler Sozialisten-Kongress zu Stuttgart August 18 to 24, 1907. Berlin 1907, pp. 40–48. ( Digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- Karl Marx and his life's work. Molkenbuhr, Elberfeld 1913.

- Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. Red Flag, Berlin 1919.

- We accuse! A contribution to the process of social revolutionaries . Publishing house of the Communist International, Hamburg 1922.

- In the liberated Caucasus. Publishing house for literature and politics, Vienna / Berlin 1926.

- The meaning of the building Soviet Union for the German working class . Association of International Publishing Houses, Berlin 1926. MDZ Reader

- Memories of Lenin. Publishing house for literature and politics, Vienna / Berlin 1929.

- Hunger May , Blood May, Red May! Carl Hoym, Hamburg / Berlin 1932.

- Accused Hitler. Protocols, eyewitness reports and factual reports from the fascist torture hells in Germany Clara Zetkin calls for the International Aid Week of the IRH (June 17-25 , 1933). Mopr-Verlag, Zurich 1933.

- Collected works published posthumously:

- Selected speeches and writings. Three volumes. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1957–1960.

- I want to fight where life is. A selection of writings and speeches. Dietz-Verlag, Berlin 1955.

- The war letters (1914–1918) . Volume 1 by Clara Zetkin. The letters 1914–1933 , edited by Marga Voigt. Karl Dietz Verlag, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-320-02323-2 .

- as a translator

- Edward Bellamy : A look back from 2000 to 1887 . JHW Dietz Nachf., Stuttgart 1914.

Works

- Memories of Lenin. Talks on the question of women . Verlag Wiljo Heinen, Berlin and Böklund 2019, ISBN 978-3-95514-038-0 .

- On the history of the proletarian women's movement in Germany. 3. Edition. Verlag Marxistische Blätter, Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-88012-532-5 .

- Art and the proletariat. 2nd Edition. Dietz-Verlag, Berlin 1979.

- For Soviet power: articles, speeches and letters; 1917-1933. Verlag Marxistische Blätter, Frankfurt am Main 1977, ISBN 3-88012-494-9 .

- Revolutionary educational policy and Marxist pedagogy. Selected speeches and writings. Volk und Wissen publishing house, Berlin 1983.

- Memories of Lenin. With an appendix. From the correspondence between Clara Zetkins and VI Lenin and NK Krupskaja . Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1957.

literature

Biographies

- Zetkin, Clara . In: Hermann Weber , Andreas Herbst : German Communists. Biographical Handbook 1918 to 1945. 2., revised. and strong exp. Edition. Karl Dietz Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-320-02130-6 .

- Florence Hervé (ed.): Clara Zetkin or: Fight where life is. 4th, updated & extended edition, Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin 2020. ISBN 978-3-320-02372-0 (first 2007).

- Tânia Pushnerat : Clara Zetkin. Bourgeoisie and Marxism. A biography. Klartext-Verlagsgesellschaft, Essen 2003, ISBN 3-89861-200-7 (biography).

- Gilbert Badia: Clara Zetkin. A new biography . Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1994.

- Luise Dornemann : Clara Zetkin. Life and Work , 9th, revised. Ed., Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1989 (first 1957).

- Clara Zetkin. An anthology in memory of the great fighter. Moscow / Leningrad 1934.

- Essays, articles and sources

- Martin Grass: Letters from Clara Zetkins in the archive and library of the labor movement in Stockholm. In: Yearbook for research on the history of the labor movement. Issue III / 2011.

- Ulla Plener (Ed.): Clara Zetkin in her time - new facts, insights, evaluations . (= Manuscripts. Volume 76). Karl Dietz Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-320-02160-3 , rosalux.de (PDF)

- Gisela Notz : Clara Zetkin and the international socialist women's movement. In: Year Book for Research on the History of the Labor Movement . Issue III / 2007.

- Setsu Ito: Clara Zetkin in her time - for a historically accurate assessment of her theory of women's emancipation. In: Year Book for Research on the History of the Labor Movement. Issue III / 2007.

- Jens Becker: Zetkin, Clara Josephine b. Eißner. In: Manfred Asendorf, Rolf von Bokel (ed.): Democratic ways. German résumés from five centuries. JB Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 1997, ISBN 3-476-01244-1 , pp. 706-708.

- Mascha Riepl-Schmidt : Progrom mood at the gates of the capital. Clara Zetkin in her time in Sillenbuch , in: Herrmann G. Abmayr (Ed.): Sillenbuch & Riedenberg: two town-villages tell from their history , Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-926369-08-6 , pp. 104–113.

- Maja Riepl-Schmidt : Clara Zetkin. The "red emanze" . In: Maja Riepl-Schmidt (Hrsg.): Against the overcooked and ironed out life. Women's emancipation in Stuttgart since 1800 . Silberburg, Stuttgart 1990, ISBN 3-925344-64-0 , p. 157-172 .

- Ina Hochreuther: Women in Parliament. Southwest German MPs since 1919. Published by the State Center for Political Education on behalf of the State Parliament. Theiss-Verlag, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-8062-1012-8 .

- Marta Globig, H. Karl: Zetkin, Clara Josephine geb. Eißner. In: History of the German labor movement. Biographical Lexicon . Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1970, pp. 497-501.

Television documentary

- Clara Zetkin - the incorruptible . A film by Ernst-Michael Brandt as part of the "German CVs" series. First broadcast on June 1, 2008 on MDR .

- TV documentary play Clara Zetkin , GDR 1975, with Barbara Dittus

- Beate Thalberg : Universum History : The Unyielding - Three women and their way to the right to vote , Austria 2019, with Anna Brüggemann (Clara Zetkin), Katharina Haudum ( Adelheid Popp ) and Marie-Luise Stockinger ( Hildegard Burjan )

Web links

- Literature by and about Clara Zetkin in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Clara Zetkin in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Clara Zetkin in the press kit of the 20th century of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Search for Clara Zetkin in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Works by Clara Zetkin in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Literature by and about Clara Zetkin Staatsbibliothek Berlin

- Kai-Britt Albrecht and Levke Harders: Clara Zetkin. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG ), there also age president Clara Zetkin opened the Reichstag on August 30, 1932 ( RealPlayer ; text and audio document)

- Biography at the main state archive in Stuttgart

- Speeches and writings of Zetkin in the Marxists Internet Archive

- Clara Zetkin on FemBio with a detailed list of links and literature

- Biography of Klara Zetkin . In: Wilhelm H. Schröder : Social Democratic Parliamentarians in the German Reich and Landtag 1876–1933 (BIOSOP)

- Nick Brauns: Emancipation through class struggle. For the 150th birthday of the communist, women's rights activist and anti-fascist Clara Zetkin . originally published in Young World , July 5, 2007

- Wolfram Klein: Clara Zetkin: “Socialism will only win with proletarian women!” Article on the website of the Socialist Alternative (SAV) , July 5, 2007

- 150th birthday of Clara Zetkin Federal Archives

- Nina Gunic: The legacy of Clara Zetkin. Critical appraisal 2012 (with further picture)

- Clara Zetkin and the Communist International Letter Kostja Zetkins to Elisabeth Mayer, a friend of the family

Individual evidence

- ^ Clara Zetkin in the database of members of the Reichstag

- ↑ a b Hoppe, Bert: In Stalin's Followers. Moscow and the KPD 1928-1933 . Munich 2007, p. 58 .

- ^ Müller, Reinhard: "Friends of the Soviet Union". Voluntary blindness and organized delusion . In: Haarmann, Hermann / Hartmann, Anne (ed.): "On to Moscow!" Travel reports from exile . Baden-Baden 2018, p. 189–217, here p. 194 f .

- ↑ Haferkorn, Katja: Clara Zetkin. For the Soviet power. Articles, speeches and letters 1917-1933 . Dietz, Frankfurt a. M. 1977, p. 386 f .

- ^ Website of the Zschopau city administration - timetable , accessed on November 19, 2017.

- ↑ Ernst Schattner (1879–1944) is the stepson of Eduard Bernstein. See Marx-Engels-Jahrbuch 2004, p. 194.

- ↑ Summary of Zetkin's contribution to the International Socialist Congress 1889 (Minutes of the International Workers' Congress in Paris. Held from July 14 to 20, 1889, Nuremberg 1890, pp. 80–85. Clara Zetkin, Selected Speeches and Writings, Volume I , Berlin 1957, pp. 3-11.) On marxists.org.

- ↑ Clara Zetkin's War Letters, Sybille Fuchs, September 30, 2016, In: World Socialist Web Site, https://www.wsws.org/de/articles/2016/12/30/zet1-d30.html

- ↑ Hannes Obermair , Carla Giacomozzi: Clara Zetkin wanted! In: City Archives Bozen (Ed.): The exhibit of the month of the City Archives Bozen . No. 43 , July 2015 ( gemeinde.bozen.it [PDF; accessed on November 15, 2015]).

- ^ The War Letters of Clara Zetkin, Sybille Fuchs, September 30, 2016. In: World Socialist Web Site, https://www.wsws.org/de/articles/2016/12/30/zet1-d30.html

- ↑ Text of the speech. on marxists.org

- ↑ Anette Schneider: Fought for peace and socialism. In: Calendar sheet (broadcast on DLF ). March 26, 2015, accessed March 26, 2015 .

- ↑ kunst-und-kultur.de

- ^ Clara Zetkin Prize. Retrieved December 13, 2018 .

- ↑ LINKE awards the Clara Zetkin Women's Prize for the first time. die-linke.de, March 12, 2011, accessed on March 21, 2011 .

- ^ Letter from Gregor Gysis to Dr. Norbert Lammert ( Memento from December 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF), accessed on May 8, 2018.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Zetkin, Clara |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Zetkin, Clara Josephine (full name); Eißner, Clara (maiden name); Zetkin, Klara (Hungarian) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | socialist-communist German politician, peace activist and women's rights activist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 5, 1857 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Wiederau , Head Office Rochlitz , Kingdom of Saxony |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 20, 1933 |

| Place of death | Arkhangelskoye , Moscow Oblast , Soviet Union |