Ludwig Kübler

Ludwig Kübler (born September 2, 1889 in Unterdill , Munich ; † August 18, 1947 in Ljubljana ) was a German general in the mountain troops in World War II . He is considered the organizer of the mountain troops and had an above-average career during the first phase of the war, before falling out of favor with Hitler in early 1942 because he did not meet the expectations placed on him as an army leader. In the second half of the war he commanded units fighting partisans . In May 1945, he fell into Yugoslav captivity and was eventually because of its draconian measures during the Eastern campaign and its committed in the Balkans war crimes to death by the strand tried and executed. A 1995 study by the Military History Research Office certified Kübler an "extremely positive attitude towards National Socialism " as well as "excessive harshness and brutality", which resulted in the renaming of a barracks named after him.

Person and personality

Little is known about Kübler's private life. He had two daughters (Elisabeth and Marianne) with his wife Johanna and lived with his family in Munich. He only seemed to have a close relationship with his boy, Hans Dauerer, who also accompanied him in his private life from 1939 to 1945. Kübler was considered a "difficult personality". On the one hand, he dealt extensively with history, was a good cellist and impressed others with his physical strength and fitness. On the other hand, he was sensitive to criticism and did not tolerate objections from subordinates. He showed himself stubborn, dogmatic and had "violent manners". His face was disfigured by large scars due to a wound in the First World War .

A short description of Ludwig Kübler also left his long-time friend Wolfgang Bernklau. He described him as a “lean figure, medium height (175 cm)”, his language was “determined, cutting, apodictic , unmelodic”. Kübler was full of job-related clichés and prejudices and had sharp self-criticism. He was also "closed, resentful and not sociable". All in all, a distant and authoritarian officer. “Noticeable human warmth, indulgent, forgiving forgetting were alien to him. As a superior and also as a court lord with jurisdiction deciding grace, he preferred to be relentlessly strict. ”That is why he was feared by his subordinates. He was not very keen on a friendly relationship and withdrew from discussions that were not about the military or war.

In the early years of his life, Kübler was more likely to be assigned to the conservative national camp until he came into closer contact with the SA and NSDAP from 1933 . From this point on he began to identify with Hitler and his movement and was soon one of the National Socialists in the officer corps of the Wehrmacht . Throughout the war he signed his orders with “ Heil Hitler ” or “Heil dem Führer”, and his division's order to attack France in 1940 was given the code name “Der Führer”. All of this at a time when the majority of officers were still limiting their greetings to what was militarily normal. In his camp there was always the flag of the movement and a picture of the “Führer”. He also took measures to indoctrinate the mountain troops in the National Socialist sense. Kübler preserved this positive attitude towards National Socialism even when he was a prisoner of war. Major General Gerhard Henke later reported on a meeting between Wehrmacht generals and representatives of the Antifa in Yugoslav captivity, at which Lieutenant General Wolfgang Hauser stated that "National Socialism was a great misfortune for our fatherland and people". Kübler then demonstratively left the meeting.

biography

Youth and early career

Ludwig Kübler was born in Unterdill near Munich in 1889 as the son of the doctor Wilhelm Kübler and his wife Rosa, nee. Born brown. He had six brothers and two sisters. In 1895, Kübler started school in Forstenried , which he left after three years in order to graduate in Munich. From 1895 to 1902 Kübler attended the Progymnasium of the Schäftlarn monastery and then the Rosenheimer Gymnasium and the humanistic Munich Ludwigsgymnasium . He graduated with a grade of 1 in all subjects in 1908.

Although entry into the renowned Maximilianeum was open to him after graduating from school , Kübler decided to pursue a career in the military and joined the 15th Bavarian Infantry Regiment on July 20, 1908 as a flag junior . After his promotion to ensign , he attended the military school in Munich from October 1, 1909 to October 14, 1910 and graduated as the fifth-best of 166 participants in his year. With effect from October 23, 1910 he received the patent for lieutenant . In the years that followed, Kübler took part in various courses with a focus on machine gun operations and was called in by his superior, Colonel Ludwig Tutschek, to organize his regiment's mobilization plans.

At the beginning of the First World War , the Royal Bavarian 15th Infantry Regiment "King Friedrich August von Sachsen" was relocated to the Western Front, where it was involved in the fighting in Lorraine and around Saint-Quentin in August and September 1914 . Kübler, who was a platoon leader in the machine gun company at the time , suffered a serious injury from shrapnel on September 24, which left a noticeable large scar on his face. Although the injury had not yet completely healed, he returned to his regiment on January 13, 1915, which was fighting on the Somme at the time . During these first months at the front, Kübler acquired the Iron Cross, 2nd and 1st class (September 16 and November 17, 1914).

From September 21, 1915 he served as an adjutant of his regiment and remained so for most of the war. The regiment was used in 1916, among others, in the Battle of Verdun and the Battle of the Somme . Since Kübler was now mainly busy with staff work, he received improvised general staff training under war conditions in the staff of the 2nd (Bavarian) Infantry Division in October 1917 . He then led the machine gun company of his main regiment from January 25 to March 31, 1918. Kübler then took over the machine gun sniper division 2 until April 11th. After a brief transfer to the 2nd Battalion of the 12th Bavarian Infantry Regiment, he was again given command of the machine gun company in the 15th Bavarian Regiment on June 26, 1918. In July he was promoted to deputy commander of the 2nd battalion. The wound suffered in 1914 broke open again, so that Kübler had to go back to the hospital. He ended the war as deputy commander of the 2nd battalion with the rank of captain and was awarded the Bavarian Order of Military Merit IV class with swords and crown as well as the Knight's Cross II class of the Saxon Order of Albrecht with swords. Three of his brothers died during the war.

Career in the Reichswehr and Wehrmacht

Promotions

- October 16, 1908 flagjunker

- February 20, 1909 Ensign

- October 23, 1910 Lieutenant

- July 9, 1915 First Lieutenant

- August 18, 1918 Captain

- August 1, 1928 Major

- April 1, 1932 Lieutenant Colonel

- July 1, 1934 Colonel

- January 1, 1938 Major General

- 1st December 1939 Lieutenant General

- 1st August 1940 General of the Infantry

- November 24, 1941 General of the Mountain Forces

(only renaming of the previous rank)

At the time of the Compiègne armistice (November 11, 1918), Kübler was in the reserve hospital in Erlangen . After his release he took over the home security company of the 15th Bavarian Infantry Regiment on February 16, 1919. With this he participated alongside the Freikorps Epp and other troops in the bloody suppression of the Munich Soviet Republic . He took part in the fighting in Augsburg from April 20 to 23 and the occupation of the Allgäu . In an assessment by his superior in August 1919, Kübler was first characterized as “cold-blooded and fearless”.

After further short-term assignments as adjutant and orderly officer of various units (infantry leaders 21 and 22) Kübler received a post on October 15, 1919 as chief of the 10th (mountain hunter) company of III. (Gebirgsjäger-) battalions in the Reichswehr-Schützen-Regiment 42 in Kempten (Allgäu) . Since his superiors campaigned for him to remain in the armed forces, he was accepted into the new Reichswehr even when they were downsized . During his time as company commander he was nicknamed "Latschen-Nurmi". This was an allusion to the Finnish long-distance runner Paavo Nurmi (1897–1973) and was intended to make it clear that Kübler always used to march persistently, even when exercising off-road.

On October 1, 1921, Kübler was transferred and now served in various higher general staffs. First he was used for four years in the troop office of the Reichswehr Ministry. This was followed on October 1, 1925 , when he was transferred to the staff of Group Command 1 in Berlin, before he was transferred to the staff of the 1st Division in East Prussia on October 1, 1927 , where he served as a teacher for general staff training. Only on June 1, 1931, Kübler again took command of a battalion of the 19th (Bavarian) Infantry Regiment in Munich. But this activity ended in September of the following year. He then took up a position as Chief of the General Staff of General Command VII in Munich. From October 1933 he also acted as Chief of Staff of the 7th (Bavarian) Division and soon reached the rank of colonel .

While he was on the staff of the General Command, Kübler maintained close contact with the NSDAP , the SA and the SS , which was due to the new recruiting policy of the Reichswehr after the arrival of the National Socialist Reichswehr Minister Werner von Blomberg (1878-1946). This operated the synchronization of the German armed forces in the sense of National Socialism and decreed that members of these organizations should be hired. Officially, the Reichswehr should benefit from their pre-military training.

With the planned expansion of the Wehrmacht to 36 divisions , it was decided to set up new mountain formations. A mountain brigade was set up as a cadre unit in Munich on June 1, 1935 , and Ludwig Kübler was entrusted with its command. Kübler thus played a key role in the organization of this large association. He supervised the expansion of their properties as well as the training and equipment of the soldiers involved. Here his inconsiderate attitude towards his own soldiers was already evident. After a maneuver, he explained to a platoon leader who had vacated his position: “There are several possibilities of defense. But if defense is ordered, every soldier fights in his position until the enemy is finished or until he himself is either shot, stabbed or slain. "

As one oriented to Italian and Swiss formations, Kübler was commanded to maneuvers of the Swiss armed forces in autumn 1935. By October 1937 the association grew to three full mountain infantry regiments (No. 98, 99 and 100) and one mountain artillery regiment 79. At the head of the mountain brigade, Kübler, who had been major general since the beginning of the year , took part in the "Anschluss" of Austria from March 12, 1938 . Already on March 23, after the bloodless occupation, the relocation of the mountain brigade to Germany began, which was then officially renamed the 1st Mountain Division on April 1, 1938 . In the same year, Kübler's division was mobilized again during the Sudeten crisis in preparation for the "Green Fall", the attack on Czechoslovakia, and relocated near the border in September. From October 1 to October 12, 1938, the 1st Mountain Division occupied part of the Sudeten area in accordance with the Munich Agreement and later returned to its garrisons.

Division commander 1939–1940

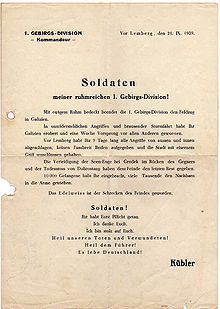

On August 25, 1939, the 1st Mountain Division received orders to mobilize . She left her garrisons two days later and was transferred to eastern Slovakia by rail to take part in the attack on Poland . The Küblers division did not cross the Slovak-Polish border until September 7, 1939 with orders to advance in the direction of Lemberg and thus prevent the Polish troops from retreating to the southeast.

The advance took place in constant skirmishes, while Kübler demanded of his soldiers not to lose contact with the evading enemy in "a ruthless forward thrust". He ordered, “where the enemy tries to stand, boldly break through his ranks, taking advantage of the engine, regardless of what is happening on the left and right, where he stubbornly defends himself with well-aimed shots of the motorized art . to wear down and to smash in the attack of the hunters ”.

After crossing the San , Kübler ordered the formation of a motorized advance force on September 10th, which had to break through the Polish units and advance to Lemberg, which later became known as the "storm drive to Lemberg". The advance troops reached their destination in the late afternoon of the following day. While unable to take the city, she stormed the heights to the west and north of it before being cut off from the rest of the division. In the following days, all parts of the division, but especially the advance division under the command of Colonel and later General Field Marshal Ferdinand Schörner (1892–1973), were attacked by more than three Polish divisions , which tried to break through to the southeast. Despite enormous efforts and extraordinarily high losses, Lemberg was not captured. On September 20, the fighting subsided after Soviet tanks appeared outside the city. According to a secret additional protocol to the Hitler-Stalin Pact , Lviv was left to the Red Army , and the mountain troops withdrew behind the San.

In the almost two weeks of fighting, the originally 17,000 strong 1st Mountain Infantry Division under Kübler's command had lost 1,402 men. Of these, 42 officers, 69 NCOs and 313 men had died. This means that almost 5.5% of the officers killed in the attack on Poland fell on Kübler's division, which was temporarily no longer fit for front use. In the ranks of the battalion and regimental commanders, criticism arose because of the high losses, for which, according to Colonel Schörner, Kübler's “ruthless forward tactics” were mainly responsible. Later authors also came to the conclusion that this brutal and ruthless approach was associated with considerable risks and, in the face of a stronger, less ailing and resigned opponent or with a little less luck, could have led to the destruction of the division. At that time the name "Bloodhound of Lemberg" was coined for Kübler in the troops and the "Sturmfahrt auf Lemberg" was nicknamed " Langemark der Gebirgsjäger".

Kübler's stubborn insistence on his decision, once made, to take Lemberg at any price, was widely criticized. The pointless run against the fortified city of a long-defeated country was considered to be of little military use. Regardless of this and despite his own heavy losses, Hitler awarded Ludwig Kübler the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross on October 27, 1939 , and shortly afterwards he was promoted to Lieutenant General .

From May 10, 1940, Kübler and the 1st Mountain Division took part in the western campaign. They marched across southern Belgium and the Meuse to the Oise Canal. The division overcame this on June 5 and advanced more than 200 kilometers. Here, too, Kübler showed harshness towards his own soldiers. For example, a rifleman named Bachl was sentenced to death for minor offenses and executed after Kübler had rejected every request for clemency. Even when the regimental commander of the 99 Mountain Infantry Regiment reported that it was not possible to hold the bridgehead during an advance across the Oise-Aisne Canal, Kübler nevertheless ordered the ruthless attack. The same happened a few days later on the Aisne in the area of the Mountain Infantry Regiment 100, where the regimental commander had reported the exhaustion of the soldiers against an attack.

After the armistice agreement was signed between France and the German Reich on June 22, 1940, the division was finally relocated to the Arras - Calais - Dunkirk area, where it was part of the 16th Army for the " Operation Sea Lion ", the planned invasion of the British Islands, was intended. Kübler was promoted to general of the infantry during this time . This was the highest rank he should ever achieve - later this was only renamed General of the Mountain Troops. After the invasion was canceled, Kübler gave command of the 1st Mountain Division to Major General Hubert Lanz (1896–1982) on October 25, 1940 and took over the XXXXIX. Mountain Army Corps as commanding general .

Corps commander 1940–1941

In his new function, Kübler was given a special role by the Wehrmacht High Command : he was to lead the " Felix company " in a key position . The company envisaged the conquest of the British fortress of Gibraltar . Together with Wolfram von Richthofen (1895–1945) he worked out the relevant plans and held several lectures until December 7, 1940 to the highest commanders in the Wehrmacht and to Hitler personally. The operation plans were approved by him and Kübler's staff was entrusted with the management. But the company, which was supposed to start on January 10, 1941, was canceled at short notice in December 1940.

Kübler and the staff of XXXXIX spent the following months. Mountain Army Corps in France, where it was ready for the company "Attila" (occupation of the rest of France ), in which the corps was to occupy Grenoble . The planning work was stopped in March 1941, when the corps was deployed on the southeastern border of the German Reich to take part in the war against Yugoslavia . On the night of April 8th to 9th, 1941, the corps crossed the Drava and advanced towards Bihać . There were only a few fights that resulted in the loss of 15 men, including 6 dead. After that the corps and its commander were billeted in Carinthia . Hitler arrived there on April 27, 1941. He dined with Kübler and the staff officers and expressed great appreciation for the mountain troops. After a brief refreshment at Lake Wörthersee , the association was relocated to Slovakia, where it was subordinate to the staff of the 17th Army . In the period from May 6 to June 16, 1941, Kübler prepared intensively for the imminent attack against the Soviet Union, undertaking field surveys himself. This was followed by the deployment of the corps on the Soviet-German border.

When the war against the Soviet Union began on June 22nd, 1941 , Küblers XXXXIX was there. Mountain Army Corps (1st Mountain Division, 68th Infantry Division, 257th Infantry Division and later 4th Mountain Division ) in the Association of Army Group South . After the border fighting, it was Kübler's corps which took Lemberg again on June 30th. There the NKVD murdered thousands of political prisoners, whereupon a pogrom against the local Jewish population broke out in the Ukrainian city in the following days (compare Hubert Lanz ). These events took place in Kübler's area of responsibility without him taking action against the riots. Over the next few weeks, the corps broke through the Stalin Line and captured Vinnytsia . After that, Kübler’s association played a decisive role in the Kessel battle near Uman in July / August 1941. Kübler later commented among members of his staff: “This battle was the culmination of my military life. Something bigger cannot keep up. ”Then the corps marched through the Nogai Steppe and into the Donets Basin , where it captured Stalino on October 21, 1941 . In November / December, however, it was forced into defense by the Soviet troops on the Mius .

During the advance, Kübler was repeatedly noticed by draconian measures against the civilian population . On June 29, 1941, for example, he issued a significant order in this regard: “The reports that civilians are plundering the battlefields to an ever greater extent are piling up. To counter this, the commanding general gives orders that all adult civilian looters are to be shot on the battlefield. ”Kübler reacted with the greatest severity in the Lemberg area. There the city commandant, Colonel Karl Wintergerst, ordered on Kübler's behalf:

“(1) Violence and threats against members of the German Wehrmacht and their retinue are punishable by death. If the perpetrators cannot be identified, the arrested hostages are subjected to reprisals. (2) Anyone who does not return to his or her place of work or quits work is shot as a saboteur. (3) […] people who give shelter to Russian soldiers and political functionaries are shot. (4) All firearms are to be delivered to the militia. Violations are punishable by the death penalty. "

Kübler's superiors did not want to support this behavior in all cases. After the Battle of Uman, Soviet soldiers attacked a German ambulance, and 19 wounded were deliberately killed. In response, Kübler proposed to the commander of the 17th Army, General of the Infantry Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel (1886-1944), to execute all captured Soviet commanding generals, division commanders and staff officers. A few days later he suggested shooting all captured Soviet generals in the future, whom he held responsible for the resistance of the Soviet soldiers, and announcing this measure to the enemy via leaflets. Stülpnagel rejected these requests, however, on the grounds that if such retaliation became known, it would provide "Russian atrocity propaganda against its own soldiers with proof of the correctness of Soviet Russian claims" that captured soldiers would be shot by the Germans.

Only Reinhold Klebe , a former member of Kübler's staff, later tried to put the general's brutality and harshness into perspective. In the club magazine of a traditional association, the “ Kameradenkreis der Gebirgstruppe ”, he pointed out that Kübler's orders never had an addition in the style of “regardless of losses” or “no matter what the cost”. In addition, Kübler had tears in his eyes when he received the list of casualties after the battle of Uman. However, the Klebes report is generally very positive and comes to the conclusion, among other things, that Kübler was not a “follower of Hitler”. It also states that Kübler had an officer brought before the court martial in Poland as early as 1939 because he had not intervened when SS units locked Jews in a synagogue and then set them on fire. Kübler also did not have the commissioner's order passed on to his divisions. However, there is no confirmation of these statements in the other available literature.

Army Commander 1941–1942

Thanks to the success of his corps, Kübler again attracted the attention of the Führer Headquarters , but not entirely without his own intervention. He wrote a report on the fighting near Uman, in which he particularly emphasized his own role ("Battle report of the XXXXIX. (Born) AK on the persecution battles from the Winnica area up to the encirclement of the enemy in the Podwyssokoje area"). He sent this report directly to the Fuehrer's headquarters and other higher departments, but without informing the Army High Command of the 17th Army (AOK 17), to which his corps was subordinate. The latter only found out about the existence of the report by chance in December 1941 and subsequently found considerable deviations from the war diaries of the army and other participating units.

In the course of the attack on Moscow , there had been a serious crisis in the area of Army Group Center after the Red Army had started a general counter-offensive on December 5, 1941. Hitler responded with a series of personal measures, such as the dismissal of some high front commanders. On December 19, 1941, he replaced General Field Marshal Fedor von Bock (1880-1945) as commander of Army Group Center and replaced him with General Field Marshal Günther von Kluge (1882-1944), who had previously commanded the 4th Army . The successor to the vacant post as commander of the 4th Army was actually intended to be the commander of Panzer Group 3 , General Georg-Hans Reinhardt (1887–1963), but due to adverse weather conditions he could not get into the army's area of operations. Thereupon Hitler surprisingly appointed Kübler as the new commander of the 4th Army. The command of the XXXXIX. Mountain Army Corps was handed over to General Rudolf Konrad (1891–1964). Due to his previous career and his intransigence towards his own soldiers, Kübler appeared in Hitler's eyes as particularly suitable to implement the order to unconditionally hold the front line. In addition, both the commander of the 17th Army, General of the Infantry Stülpnagel, and the commander of the 1st Panzer Army, Colonel General von Kleist (1881–1954), had certified Kübler 's ability to lead armies. Only General of the Infantry Erich von Manstein (1887–1973) had expressed skepticism in October.

Kübler himself found himself unable to fill this position satisfactorily. Kübler, who was used to achieving quick successes by driving the enemy in front of him, was now faced with a completely different military situation. In the winter of 1941/42 it was no longer the Wehrmacht that determined and acted, it only reacted to the enemy, which would have required a completely different style of leadership. After Kübler had only arrived at the army headquarters on the night of December 26th to 27th, he reported on January 8th, 1942 that only a "large-scale relocation" could save the 4th Army from being encircled. On January 13th he wrote again: “I have to throw myself completely into the balance, there is nothing left but evacuation.” Kübler's ineptitude was also visible to those around him. Colonel-General Franz Halder (1884–1972) noted in his diary: “He doesn't feel up to the task.” Frustrated, Kübler also sent pessimistic letters to his wife in Munich, who made no secret of it in the city's general command. There General von Waldenfels interpreted these statements as an official matter and reported them on, so that Hitler soon became aware of them. Thereupon Hitler ordered Kübler to give a lecture at the Fuehrer's headquarters. This meeting on January 20 ended with Kübler "until his health was restored" to give command to General of the Infantry Gotthard Heinrici (1886–1971). The general was released from his command on the following day and transferred to the “ Führerreserve ”.

Field Marshal von Kluge thought Kübler was overwhelmed with leading an army and noted on January 29, 1942:

"General Kübler [...] came from completely different - simple - relationships with his army, which was in a difficult situation and remained in it. Unfamiliar with the conduct of the war and the particularly difficult conditions, it became difficult for him to influence his subordinate corps commanders as the highest order and the situation required. Although personally a tough man, especially against himself, he had inhibitions about influencing the lower leadership in the sense of the clearly expressed supreme opinion of will ... He suffered from this fact, which was ultimately connected with his belief in his success Task was only minor. "

Without agency and reuse

As his biographer Roland Kaltenegger put it, Kübler now belonged to "that worn out General Guard who was already on the sidelines". After his release, Kübler moved back to his family in Munich, where he owned an official apartment at Winzererstrasse 54. The general was bitter and rarely left the apartment. From 1943, however, he kept writing letters to the Army Personnel Office in which he asked for a new command.

Only after a year and a half was the request granted. Hitler no longer wanted to entrust the general with command of an army, but on July 22, 1943 he agreed to the appointment of Kübler as " Commanding General of the Security Forces and Commander in Army Area Central ". There his main task was to fight partisans . According to his biographer Roland Kaltenegger , Kübler was determined to make the shame of Moscow forget and now to enforce every order with the greatest severity. In August Kübler had the opportunity to rehabilitate, when the 286th , 203rd and 221st security divisions he commanded succeeded in rubbing up the Soviet partisan association "Polk Grischin" in several companies. Here, too, he was again characterized by toughness and draconian measures.

Commander in the "Adriatic Coast Country"

On October 10, 1943, Kübler was appointed commander of the newly formed " Adriatic Coastal Operation Zone ", which was under the command of Army Group B (later the staff of the "Supreme Commander Southwest"). The operational zone was set up after Italy left the war and included the provinces of Udine , Gorizia , Trieste , Pula , Rijeka and the areas of Yugoslavia Ljubljana , Susak and Bakar . The general was in command of all Wehrmacht troops in this room. His skills were comparable to those of a military district commander . However, because his associations played a decisive role in the fight against partisans, his influence soon extended beyond this. The administration of the operational zone in all civil matters was incumbent on the head of the civil administration, Friedrich Rainer, with the title of "Supreme Commissioner". The Higher SS and Police Leader in Trieste Odilo Globocnik (1904–1945) also claimed competencies for himself.

Kübler's primary task, in addition to coastal protection, was the fight against Italian, Croatian and Slovenian partisans. The "relentless" fight against the strong partisan groups in the "Adriatic coastal region" had already been stated as a priority task in an order from the High Command of the Wehrmacht (OKW) on September 25, 1943. However, the fights soon proved to be ineffective and very lossy. A German service report commented: “The cleansing of the country by the Wehrmacht was only partially and incompletely successful, above all because after the rooms had been combed, the police forces were lacking to take control of the country [...] numerous Individual operations of the Wehrmacht and the police have only ever been able to achieve local improvements in the situation temporarily. ”Between January 1 and February 15, 1944, 181 attacks on the Wehrmacht occurred in the“ Adriatic coastal region ”, involving 503 soldiers (including three commanders ) were killed. Against this background, Kübler issued a corps order on February 24, 1944, in which he explained the guidelines for “fighting gangs” that were now in force. Since it was precisely this order that later led to Kübler's conviction as a war criminal, extracts from it are reproduced here.

Corps order No. 9 of February 24, 1944

II. This is a major battle on the orders of the enemy powers. [...]

IV. There is only one thing:

Terror against terror, an

eye for an eye , a

tooth for a tooth! [...]

V / 6) In combat everything is right and necessary that leads to success. I will cover any action that conforms to this principle.

V / 7) […] Captured bandits are to be hanged or shot . Anyone who voluntarily supports the bandits by providing shelter or food, by concealing their stay or by any other means, is worthy of death and must be dealt with. [...]

V / 10) Collective measures against villages etc. may only be imposed in the immediate temporal and temporal connection with combat operations and only by officers from the captain upwards. They are in place when the population has voluntarily supported the gangs in their bulk. The basic principles of the combat instructions for fighting gangs in the east also apply to the operational zone of the army corps. [...]

It is regrettable that innocent people sometimes get under the wheels in combat, but this cannot be changed. You may thank the gangs. We didn't start the gang war. [...]

It is not necessary to state more here what is required, permitted or prohibited. In the third year of the gang war, every leader knows what is due anyway. [...]

Act accordingly!

signed Kübler

General of the Mountain Troops

This order is to be distributed among the companies.

Its principles are all officers, Uffz. And Mannsch. hammer in over and over again.

The reference to the “ Combat Instructions for Combating Gangs in the East ” (RHD 6/69/1) from November 1942, which did not only apply to the “Adriatic Coast”, had far-reaching consequences. It said that when fighting partisans, considerations are “irresponsible”, that “the harshness of the measures and the fear of the expected punishments” should deter the population from supporting the resistance, as well as that against villages, the partisans had supported the use of collective punishments that could go as far as the “destruction of the entire village”. Even Kübler's restrictive formulation that the instruction only applies in “its principles” was, according to his own statement, a concession to an objection from Supreme Inspector Rainer. All in all, the corps command represented a blanket power of attorney for the recipients of the command, which was suitable to reduce their inhibitions and to assure them backing. Kübler was evidently based on a Führer's order of December 16, 1942, which had already stated: “The troops are therefore entitled and obliged to use every means in this struggle without restrictions, even against women and children, if only for the purpose Success leads. Regardless of what kind, is a crime against the German people [...] No German deployed in the fight against gangs may be held accountable in a disciplinary or court martial for his behavior in the fight against the gangs and their followers. "

In the entire formerly Italian sphere of influence in occupied Yugoslavia, the German occupation forces took action against resistance movements with great severity . Means were shootings, the destruction of houses and entire villages suspected of supporting partisans, hostage-taking and shooting of hostages and the execution of "expiatory victims" for killed German soldiers. Kübler stood out so much that he was soon referred to by his own troops as an "Adriatic fright".

In fact, the “Supreme Commissioner” Rainer intervened against the threatened forms of collective punishment , as he feared that these measures would attract the partisans and cause the Germans a considerable loss of prestige. Kübler had to change the corps command on March 14, 1944 so that collective measures could only be carried out with his consent. He also promised Rainer that he would get his approval beforehand. But also beyond that, Kübler and Rainer kept clashing. On May 19, 1944, the “Oberste Kommissar” issued an amnesty for partisans who surrendered to the German troops. Such defectors had previously been regularly executed, which meant that partisans no longer defected but fought to the end. Kübler was annoyed because this measure had not been discussed with him. It denied German troop leaders the opportunity to persuade partisans to give up themselves with a promise of amnesty in special situations. The influence of Kübler and his staff changed the provisions of the amnesty in such a way that they were no longer applicable to German deserters or to those who had killed German soldiers. The latter should be convicted of murder by the ordinary courts.

The Central Office of the State Judicial Administrations for Solving National Socialist Crimes (ZStLJV) alone has fifty cases of National Socialist acts of violence on record in the "Adriatic Coastal Operation Zone", for which Kübler is responsible for the service. However, these did not lead to legal proceedings because Kübler was executed as the main culprit in 1947.

Capture and execution

On September 28, 1944, Kübler's staff was transferred to General Command LXXXXVII for “political reasons” . Army Corps renamed, separated from the Southwest Command Area and subordinated to the Southeast Command Area. From February 1945 on there were violent retreat fighting between the Wehrmacht and partisan units. Kübler received from the Commander-in-Chief of the Southeast Colonel-General Alexander Löhr (1885-1947) the order to defend the port city of Rijeka as long as possible. Although the position in the north and south was bypassed by opposing troops and the subordinate commanders pointed out the possibility of encircling, Kübler insisted on his order. It was not until May 1, 1945 that Kübler ordered the breakthrough to the north in order to reach the imperial border - too late, as it turned out. Kübler's corps was surrounded by the Yugoslav People's Liberation Army in the Trieste area . According to the regimental commander Carl Schulze, Kübler himself is said to have suffered a nervous breakdown during the subsequent hopeless fighting. Already on May 5, the Commander-in-Chief Southeast received permission to begin surrender negotiations. This started on May 6th. On the same day Kübler was wounded and General Hans von Hößlin took over command in his place. Hößlin surrendered on May 7, 1945 on condition that the German soldiers would be released back home by the end of 1945.

Kübler's wound resulted from enemy shell fire that tore open the right half of his face. As a result, he passed his boy off as an assistant doctor in order to escape persecution by the partisans. However, both were betrayed by a Slovenian and taken to Rijeka. There the general lay in a hospital for several days. On May 12, shortly after the unconditional surrender , the Yugoslav side declared that passage of the surrender agreement that provided for the release of the German troops to be null and void and sent the German prisoners of war on “expiatory marches” to prisoner-of-war camps . Kübler also took part in these marches until he arrived at the Danube General Camp in Belgrade in July 1945 . There he spent the next two years under heavy guard.

Between July 10 and 19, 1947, the trial of 14 officers took place in front of the military criminal chamber in Ljubljana , among them Gauleiter Friedrich Rainer , SS-Sturmbannführer Josef Vogt and Lieutenant General Hans von Hößlin as well as Kübler. He was incriminated by his former subordinates and staff officers. On July 17, he was sentenced to death by hanging for “criminal acts against the people and the state” . After his petition for clemency was rejected , he was finally executed in Ljubljana on August 18, 1947 , just like his brother, Lieutenant General Josef Kübler (1896–1947) a few months earlier .

Controversy in the Federal Republic

In Germany, Kübler's family received no news of the general's fate, so his wife Johanna tried to find advocates for her husband in 1948. However, there was hardly anyone who wanted to take on this task. In the first years of the Bundeswehr , the Federal Ministry of Defense left it to the troops to decide for themselves how to name their properties. Due to their initiatives, a number of barracks were named after former Wehrmacht officers loyal to Hitler. “The fact that these officers included anti-Semites , avowed National Socialists from the very beginning and war criminals was either not sufficiently known to the responsible troop commanders or, what is more likely, was of little importance to them.” In 1964, the “ Pionier - Barracks "(former" Ludendorff barracks ") in Mittenwald renamed" General Kübler barracks ". General Gartmayr was responsible for this as the commander of the 1st Mountain Division of the Bundeswehr . He had belonged to Kübler's staff from October 1939 to May 1940 and applied for this designation to the Federal Ministry of Defense. As the organizer of the German mountain troops in World War II, Kübler was (and is) honored in the traditional associations. The general is still glorified in Landser novels by the former mountain trooper Alex Buchner. On the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the 1st Mountain Division of the Bundeswehr on February 17, 1986, Franz Josef Strauss announced: “General Ludwig Kübler was a role model for the German mountain troops, both as a person and as a soldier. The troops owe him a lot to this day. "

In February 1988 the Catholic peace movement Pax Christi demanded the renaming of the " Generaloberst Dietl barracks" in Füssen (today's Allgäu barracks ) and the "General Kübler barracks". However, the Federal Ministry of Defense ( headquarters of the armed forces ) refused to implement the relevant decisions of the Petitions Committee . This was justified, among other things, by the fact that the affected population and the soldiers were in favor of keeping the names. The early debate was made more difficult by the fact that there were no critical publications on Kübler's person and the Yugoslav files on his criminal trial were inaccessible. On the latter point, nothing has changed until 2008. In 1993 and 1994 two books by the publicist and journalist Roland Kaltenegger were published, in which he made Kübler's person known to a larger audience for the first time outside of the traditional mountain hunter associations and referred to his draconian measures. In 1995 a book by the founder and spokesman of the “Initiative against False Glory”, Jakob Knab , was published, in which he referred to the books of Kaltenegger and denounced the problem: “A truly scandalous connection between the war criminal Kübler and the preparation for global combat operations.”

In the summer of 1995, the SPD MP Hans Büttner introduced a formal motion to the Bundestag in which he called for the barracks in question to be renamed on behalf of 85 MPs. The FDP - Group joined the application and defense minister Volker Ruhe ( CDU ) became, especially in view of the expected Bundeswehr mission in Yugoslavia (see Bundeswehr missions abroad ), under increasing pressure. The strong emotional dispute was also influenced by the fact that there was no biography about Kübler so far and therefore only a lack of information about him was available. To remedy the situation, Rühe commissioned a study from the Bundeswehr Research Office for Military History . In the final consideration, the author of the study sums up:

“In his ambition that the troops subordinate to him should be the best of all Wehrmacht units, he went far beyond the goals that can still be represented on a generous scale. With the extremely ambitious intention of always fighting at the head of the attack, he urged his troops on regardless of personnel losses and thus gave the strong impression of inhuman brutality and a gambler. This impression is reinforced when his attitude towards the enemy is considered, as is expressed in his demands for reprisals in the Russian campaign and the fight against partisans [...] After these particularly negative features in his personality, the general's political view is also shaped by one extremely positive attitude towards National Socialism. "

His proposal to shoot all captured Soviet commanding generals, division commanders and staff officers in retaliation for the killing of 19 German soldiers following the Uman Kessel Battle in 1941, was seen as an unmistakable invitation to commit a war crime that was clearly against the provisions of the Hague Land Warfare Code violated, as did his corps order No. 9 of February 24, 1944. After this unflattering report was available, on November 9, 1995 the Minister of Defense ordered the renaming of the “General Kübler barracks” to “ Karwendel barracks ”. This happened against the bitter resistance of the so-called comrades circle of the mountain troops , which organized a signature campaign against the renaming, in which thousands of its members and supporters took part. Three years later, in 1998, the first and (besides the MGFA study) so far the only biography of Ludwig Kübler was published, again by Roland Kaltenegger. However, this did not reach a scientific level, so that the finding from the MGFA study that a critical biography is still pending remains unchanged.

literature

- Dermot Bradley (Ed.): The Generals of the Army 1921-1945 . Vol. 7, Biblio Verlag, Bissendorf 2004, ISBN 3-7648-2902-8 , pp. 267-269.

- Erich Hesse: The Soviet Russian partisan war 1941 to 1944 as reflected in German combat instructions and orders . Verlag Musterschmidt, Göttingen 1969 (= studies and documents on the history of the Second World War . Vol. 9).

- Roland Kaltenegger : Operation Zone “Adriatic Coastal Land” - The Battle for Trieste, Istria and Fiume 1944/45 . Verlag Stocker, Graz / Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-7020-0665-6 .

- Roland Kaltenegger: Schörner - Field Marshal of the last hour . Herbig Verlag, Munich / Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-7766-1856-6 .

- Roland Kaltenegger: Ludwig Kübler - General of the mountain troops , Motorbuch-Verlag, Stuttgart 1998. ISBN 3-613-01867-5 .

- Reinhold Klebe : General Ludwig Kübler . In: The Mountain Troop . Bulletin of the comrades group of the mountain troops . 1985, No. 2, pp. 8-12.

- Jakob Knab : False Glory - The Bundeswehr's understanding of tradition . Verlag Links, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-86153-089-9 .

- Hermann Frank Meyer : Bloody Edelweiss - The 1st Mountain Division in World War II . Verlag Ch. Links, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-86153-447-1 .

- Klaus Reinhardt : The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1972 (= contributions to military and war history . Vol. 13).

- Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995 (unpublished).

- Gerhard Schreiber : The Wehrmacht and the partisan war in Italy . In: Political Change, Organized Violence and National Security . R. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-486-56063-8 , pp. 251-268 (= contributions to military history . Vol. 50).

- Christian Streit: No comrades - the Wehrmacht and the Soviet prisoners of war 1941–1945 . 2nd Edition. Dietz-Verlag, Bonn 1991, ISBN 3-8012-5016-4 .

- Karl Stuhlpfarrer : The operational zones “Alpine Foreland” and “Adriatic Coastal Land” 1943–1945 . Hollinek publishing house, Vienna 1969.

- Hans Umbreit: German rule in the occupied territories 1942–1945 . In: The German Reich and the Second World War . Vol. 5/2, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-421-06499-7 , pp. 3–254.

- Ralph Giordano : The traditional lie. From the warrior cult in the Bundeswehr . Kiepenheuer and Witsch, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-462-02921-5 .

Web links

- Bo Adam: What do the people have against Kübler? In: Berliner Zeitung of October 26, 1995

- Literature by and about Ludwig Kübler in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Roland Kaltenegger: Ludwig Kübler - General of the mountain troops . Stuttgart 1998, p. 274 f.

- ^ Hermann Frank Meyer: Bloody Edelweiss - The 1st Mountain Division in World War II . Berlin 2008, p. 15; Charles B. Burdick: Hubert Lanz - General of the mountain troops . Osnabrück 1988, p. 78.

- ↑ a b Roland Kaltenegger: Ludwig Kübler - General of the mountain troops . Stuttgart 1998, p. 304 f.

- ↑ a b Klaus Schönherr : Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 20.

- ↑ Hans-Erich Volkmann: On the responsibility of the Wehrmacht . In: RD Müller, HE Volkmann: The Wehrmacht: Myth and Reality . Munich 1999, p. 1199.

- ^ Roland Kaltenegger: Ludwig Kübler - General of the mountain troops . Stuttgart 1998, p. 355 f.

- ↑ Quoted from: Kurt W. Böhme: On the history of the German prisoners of war of the Second World War - The German prisoners of war in Yugoslavia 1941–1949 . Vol. 1/1, Munich 1962, p. 293.

- ↑ a b Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 2.

- ↑ Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 2 f.

- ↑ a b Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 3.

- ↑ Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 4 and p. 23.

- ↑ Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 4.

- ^ Roland Kaltenegger: Ludwig Kübler - General of the mountain troops . Stuttgart 1998, pp. 15-18.

- ↑ a b c d e Dermot Bradley (ed.): Die Generale des Heeres 1921–1945 . Vol. 7, Bissendorf 2004, p. 267 f.

- ↑ Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 4 f.

- ↑ Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 5.

- ^ Reinhold Klebe: General Ludwig Kübler . In: The Mountain Troop . 1985, issue 2, p. 8 f.

- ↑ a b Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 6.

- ^ Reinhold Klebe: General Ludwig Kübler . In: The Mountain Troop . 1985, issue 2, p. 9.

- ↑ Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 8; BA-MA (RH 28-1 / 256, Bl. 12) Divisional report on the campaign in Poland in 1939 . P. 11.

- ↑ Details of the fighting in: Hermann Frank Meyer: Bloody Edelweiss - The 1st Mountain Division in World War II . Berlin 2008, pp. 27-30; Nikolaus von Vormann: The 1939 campaign in Poland . Weissenburg 1958, p. 97 f, p. 144.

- ↑ BA-MA (RH 28-1 / 256, sheet 53).

- ^ Roland Kaltenegger: Ludwig Kübler - General of the mountain troops . Stuttgart 1998, p. 90.

- ^ Roland Kaltenegger: Schörner - Field Marshal of the last hour . Munich / Berlin 1994, p. 157.

- ↑ Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 8.

- ↑ According to the later VdK President Karl Weishäupl , see: Roland Kaltenegger: Ludwig Kübler - General der Gebirgstruppe . Stuttgart 1998, p. 90.

- ^ A b Hermann Frank Meyer: Bloody Edelweiss - The 1st Mountain Division in World War II . Berlin 2008, p. 30.

- ^ Roland Kaltenegger: Schörner - Field Marshal of the last hour . Munich / Berlin 1994, p. 335; From a case of the greatest mildness reported: Reinhold Klebe: General Ludwig Kübler . In: The Mountain Troop . Association magazine of the comrades group of the mountain troops , 1985, issue 2, p. 10.

- ↑ Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 9 f.

- ^ Hans-Adolf Jacobsen: Introduction . In: Percy M. Schramm (Ed.): War Diary of the High Command of the Wehrmacht . Vol. 1, Bonn 2002, p. 205.

- ↑ Percy M. Schramm (Ed.): War diary of the High Command of the Wehrmacht . Vol. 1, Bonn 2002, p. 153.

- ^ Roland Kaltenegger: Ludwig Kübler - General of the mountain troops . Stuttgart 1998, p. 144 f.

- ↑ Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 11.

- ↑ Details on the pogroms in: Hermann Frank Meyer: Bloody Edelweiss - The 1st Mountain Division in World War II . Berlin 2008, pp. 58-64.

- ↑ In detail: Hans Steets: Gebirgsjäger bei Uman - Die Korpsschlacht des XXXXIX. Mountain Army Corps near Podvyssokoye, 1941 . Heidelberg 1955. (= The Wehrmacht in combat . Vol. 4).

- ^ Reinhold Klebe: General Ludwig Kübler . In: The Mountain Troop . 1985, No. 2, p. 10.

- ^ Diary XXXXIX. (Geb.) AK June 29, 1941, printed in: Roland Kaltenegger: Ludwig Kübler - General der Gebirgstruppe . Stuttgart 1998, p. 164.

- ^ Order of the city commandant, printed in: Roland Kaltenegger: Ludwig Kübler - General der Gebirgstruppe . Stuttgart 1998, p. 168f; BA-MA (RH 24-49 / 14).

- ↑ Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 12.

- ^ Christian Streit: No Comrades - The Wehrmacht and the Soviet Prisoners of War 1941–1945 . Bonn 1991, p. 347 (fn. 158).

- ^ Hermann Frank Meyer: Bloody Edelweiss - The 1st Mountain Division in World War II . Berlin 2008, p. 68; BA-MA (RH 24-49 / 161), telex to AOK 17, Annex 63, p. 158.

- ^ Reinhold Klebe: General Ludwig Kübler . In: The Mountain Troop . 1985, No. 2, pp. 9-11.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 . Stuttgart 1972, p. 230.

- ↑ a b Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 14.

- ↑ Both quotations from: Klaus Reinhardt: Die Wende before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 . Stuttgart 1972, p. 246.

- ↑ Hans-Adolf Jacobsen (Ed.): Colonel General Halder - War Diary . Vol. 3, Stuttgart 1964, p. 388.

- ^ Roland Kaltenegger: Ludwig Kübler - General of the mountain troops . Stuttgart 1998, p. 270.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 . Stuttgart 1972, p. 251.

- ↑ Quotation can be found in: Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 14f; BA-MA (Pers 6/243, Bl. 10).

- ^ Roland Kaltenegger: Schörner - Field Marshal of the last hour . Munich / Berlin 1994, p. 154.

- ^ Roland Kaltenegger: Ludwig Kübler - General of the mountain troops . Stuttgart 1998, p. 278.

- ↑ Erich Hesse: The Soviet Russian Partisan War 1941 to 1944 in the mirror of German combat instructions and orders . Göttingen 1969, p. 216 f.

- ^ A b Karl Stuhlpfarrer: The operational zones “Alpine Foreland” and “Adriatic Coastal Land” 1943–1945 . Hollinek publishing house, Vienna 1969, p. 76.

- ^ A b Hans Umbreit: German rule in the occupied territories 1942–1945 . Stuttgart 1999, p. 71.

- ^ Hans Umbreit: German rule in the occupied territories 1942-1945 . Stuttgart 1999, p. 80.

- ↑ Quoted from: Karl Stuhlpfarrer: The operational zones “Alpine Foreland” and “Adriatic Coastal Land” 1943–1945 . Hollinek Verlag, Vienna 1969, p. 93.

- ↑ Leadership of the gang fight, corps command No. 9 , Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv RW4 / v.689; Quoted from: Roland Kaltenegger: Operation zone “Adriatic coastal land” - The struggle for Trieste, Istria and Fiume 1944/45 . Graz / Stuttgart 1993, p. 66 f; Gerhard Schreiber: The Wehrmacht and the partisan war in Italy . P. 262.

- ^ Gerhard Schreiber: The Wehrmacht and the partisan war in Italy . P. 253.

- ^ Gerhard Schreiber: The Wehrmacht and the partisan war in Italy . P. 261 f.

- ↑ Quoted from: Gerhard Schreiber: The Wehrmacht and the Partisan War in Italy . P. 257.

- ^ Hans Umbreit: German rule in the occupied territories 1942-1945 . Stuttgart 1999, p. 80 f.

- ↑ Jakob Knab: False Glorie - The traditional understanding of the Bundeswehr . Berlin 1995, p. 66.

- ↑ Karl Stuhlpfarrer: The operational zones “Alpine Foreland” and “Adriatic Coastal Land” 1943–1945 . Hollinek Verlag, Vienna 1969, p. 93.

- ↑ Karl Stuhlpfarrer: The operational zones “Alpine Foreland” and “Adriatic Coastal Land” 1943–1945 . Hollinek publishing house, Vienna 1969, p. 93 f.

- ↑ Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 28, fn. 96.

- ^ Roland Kaltenegger: Ludwig Kübler - General of the mountain troops . Stuttgart 1998, p. 276.

- ↑ Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 19; BA-MA (RH 22/297, Bl. 10-13).

- ↑ Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 19.

- ↑ On the circumstances there also: Kurt W. Böhme: On the history of the German prisoners of war of the Second World War - The German prisoners of war in Yugoslavia 1941-1949 . Vol. 1/1, Munich 1962, pp. 175-179 and 292-293.

- ^ Hermann Frank Meyer: Bloody Edelweiss - The 1st Mountain Division in World War II . Berlin 2008, p. 667 f; Kurt W. Böhme: On the history of the German prisoners of war of the second world war . Volume I, Part 2: The German prisoners of war in Yugoslavia 1949–1953 . Munich 1964, p. 21.

- ↑ Wolfram Wette: The Wehrmacht. Enemy images - war of extermination - legends . Frankfurt 2002, p. 254.

- ^ Roland Kaltenegger: Ludwig Kübler - General of the mountain troops . Stuttgart 1998, p. 306 f.

- ↑ Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 1.

- ↑ Alex Buchner: Kampfziel Lemberg - The route of action of the 1st Mountain Division in the war against Poland (No. 1545); ders .: Decision in the West - 1940 War against France - The fighting path of the 1st Mountain Division under General Ludwig Kübler (No. 2316)

- ↑ Ralph Giordano: The traditional lie. From the warrior cult in the Bundeswehr . Kiepenheuer and Witsch, Cologne 2000, p. 300; The mountain troops . Bulletin of the comrades group of the mountain troops , Munich, No. 1/1996.

- ↑ German Bundestag Printed Matter 13/1628 of 2 June 1995

- ↑ Roland Kaltenegger: Operation Zone “Adriatic Coastal Land” - The Battle for Trieste, Istria and Fiume 1944/45 . Stocker publishing house , Graz / Stuttgart 1993; Roland Kaltenegger: Schörner - Field Marshal of the last hour . Herbig Verlag, Munich / Berlin 1994.

- ↑ Jakob Knab: False Glorie - The traditional understanding of the Bundeswehr . Berlin 1995, p. 93.

- ↑ Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995.

- ↑ Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 20 f; quoted from: Ralph Giordano: The traditional lie. From the warrior cult in the Bundeswehr . Kiepenheuer and Witsch, Cologne 2000, p. 299.

- ↑ Klaus Schönherr: Scientific study - General of the mountain troop Ludwig Kübler . Military History Research Office, Potsdam 1995, p. 20 f.

- ^ Hermann Frank Meyer: Bloody Edelweiss - The 1st Mountain Division in World War II . Verlag Links, Berlin 2008, p. 678.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Kübler, Ludwig |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German officer, most recently general of the mountain troops in World War II |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 2, 1889 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Unterdill |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 18, 1947 |

| Place of death | Ljubljana |