Middle Greek language

| Middle Greek | ||

|---|---|---|

| Period | 600-1453 | |

|

Formerly spoken in |

Territory of the Byzantine Empire , southern Balkan Peninsula, southern Italy, Asia Minor, Black Sea coast, east coast of the Mediterranean and today's Egypt | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

- |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

grc (historical Greek language until 1453) |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

grc (historical Greek language until 1453) |

|

Under central Greek is commonly understood language level of the Greek between the beginning of the Middle Ages to 600 and the conquest of the city of Constantinople Opel by the Ottomans since this date usually the end of the Middle Ages for South Eastern Europe is defined 1453. From the 7th century onwards, Greek was the sole administrative and state language of the Byzantine Empire ; the language level at that time is therefore also known as Byzantine Greek ; the term Medieval Greek is also used in English and Modern Greek .

The beginning of this language level is sometimes dated as early as the 4th century, either when the main imperial residence was relocated to Constantinople in 330 or the division of the empire in 395 , but this approach is based less on cultural linguistic developments than on political developments therefore quite arbitrary. It was not until the 7th century that the Eastern Roman-Byzantine culture was subject to such massive changes that it makes sense to speak of a turning point. Medieval Greek is the link between the ancient and modern forms of language, because on the one hand its literature is still strongly influenced by ancient Greek and on the other hand almost all the peculiarities of modern Greek could develop in the spoken language at the same time .

Research into the Middle Greek language and literature is a branch of Byzantine Studies or Byzantinology, which deals comprehensively and interdisciplinary with the history and culture of the Byzantine world.

History and dissemination

With the establishment of a second Roman imperial court in Constantinople in the 4th century, the political center of the Roman Empire moved into a Greek-speaking environment, especially after the actual division of the empire in 395 . Latin initially remained the language of the court and the army as well as official documents in Ostrom , but began to wane from the 5th century onwards. However, numerous Latin loanwords penetrated Greek at that time. From the middle of the 6th century, legislative amendments were mostly written in Greek, and parts of the Latin Corpus iuris civilis were gradually translated into Greek. Under Emperor Herakleios (610-641), who also assumed the Greek title of ruler βασιλεύς ( Basileus ) in 629 , Greek finally became the official state language of Eastern Rome , which long after the fall of Western Rome was known as Ῥωμανία (Romanía) , its inhabitants as Ῥωμαῖοι ( Rhōmaioi 'Romans').

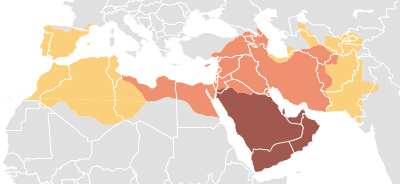

The number of Greek native speakers is estimated around 600 at a good third of the Eastern Roman population, i.e. around ten to fifteen million people, whereby the core area of the language was in the ancient settlement areas of the Greeks , mainly the southern Balkan peninsula and the western part of Asia Minor . The number of those who knew how to communicate in Greek, however, must have been much larger. The Eastern Roman cities were also still strongly influenced by Greece. In large parts of the Eastern Roman Orient, however, the colloquial language was Syriac ( Aramaic ).

The south and east of the empire were then occupied by the Persian Sassanids in 603–619 and, after being retaken by Herakleios (628), conquered by the Arabs a few years later as part of the Islamic expansion . Alexandria , a center of Hellenistic culture and language, fell to the Arabs in 642. In 693 Greek was replaced by Arabic as the official language in the conquered territories. As a result, the Greek was very much pushed back in these areas in the early Middle Ages.

The remaining core regions of the Eastern Roman and Byzantine Empire, Asia Minor and Hellas, were also the areas most strongly influenced by Greece. However, the popular Greek language that emerged from the Koine was very different from the language of the educated, which artificially adhered to many forms of ancient Greek . One speaks here of a diglossia (see below).

Turkic peoples with the Seljuks invaded the sparsely populated interior of Anatolia from the late 11th century onwards , who then advanced westward against the Greek-speaking area. With the conquest of Constantinople (1453), Athens (1456), the Peloponnese (1459/60) and the Empire of Trebizond (1461) by the Ottomans, the status of Greek as the state language ended until the emergence of modern Greece in 1832. Language forms after 1453 is called Modern Greek .

Forms of speech

The traditional texts in the Middle Greek language are far less extensive and diverse than those from ancient Greek times. In particular, the vernacular Middle Greek is only documented in longer texts from the 12th century: the vernacular was so frowned upon among Byzantine scholars that vernacular texts were even destroyed.

Language dualism

The diglossia of the Attic literary language and the constantly developing spoken vernacular began as early as the Hellenistic period . After the end of late antiquity , this gap became obvious. The medieval Koinē (common language), which was still influenced by the Attic and remained the literary language of Middle Greek for centuries, preserved a level of Greek that was no longer spoken.

The literature preserved in the Attic literary language concentrated largely on the extensive historiography (chronicles as well as classicistic, contemporary historical works), theological writings and the recording of legends of saints . Poetry can be found in hymn poetry and ecclesiastical poetry. Quite a few of the Byzantine emperors were active as writers themselves and wrote chronicles or works on Byzantine statecraft, strategic or philological writings. There are also letters, legal texts and various directories and lists in the Middle Greek language.

Concessions to spoken Greek can be found variously in the literature: Johannes Malalas ' chronography from the 6th century, the Chronicle of Theophanes (9th century) and the works of Konstantin Porphyrogennetos (mid 10th century) lean in word choice and Grammar to the respective vernacular language of their time, but do not use everyday language, but largely follow the Koinē handed down from ancient Greek in terms of morphology and syntax.

The spoken form of language was referred to with terms such as γλῶσσα δημώδης glossa dimodis ('popular language'), ἁπλοελληνική aploelliniki ('simple [language]'), καθωμιλημένη kathomilimeni ('spoken' Romai ] ') or Ῥωήμϊ ( language) or ω ( . There are very few examples of purely vernacular texts from before 1200. They are limited to quoted mocking verses, proverbs and occasionally particularly common or untranslatable formulations that have penetrated the literature. Vulgar Greek poems from literary circles in Constantinople are documented from the end of the 11th century.

Only with the Digenis Akritas , a collection of heroic songs from the 12th century, which were later compiled into a verse-epic, is a literary work written entirely in the vernacular. As a counter-reaction to the renaissance of the Attic under the Comnenen dynasty in works such as Psellos' Chronographie (mid-11th century) or the Alexiad , the biography of Emperor Alexios I by his daughter Anna Komnena , which was written about a century later, ceased the 12th century about the same time as the French chivalric novel , the vulgar Greek Versepik to light. In a fifteen-syllable blank verse ( versus politicus ) it dealt with ancient and medieval heroic legends, but also animal and plant stories. The chronicle of Morea , which was also written in verse in the 14th century and which has also been handed down in French, Italian and Aragonese and describes the history of the French feudal rule in the Peloponnese, is unique.

The earliest prose evidence of Vulgar Greek exists in some documents from the 10th century written in Lower Italy. The later prose literature consists of folk books, collections of laws, chronicles and paraphrases of religious, historical and medical works. The dualism of literary and popular language was to persist well into the 20th century, before the Greek language question was decided in 1976 in favor of the popular language .

Dialects

It is noteworthy that despite its widespread use in the eastern Mediterranean, the Greek vernacular did not split up into numerous new languages like Vulgar Latin , but remained a relatively uniform language area. An exception is the Greek on the southern coast of the Black Sea , the Pontic language , which did not follow many developments in the Middle Greek vernacular. Dialects based on the Koinē emerged around the turn of the millennium. Dialect forms of older origin have been preserved in the southern Italian exclaves of Griko and in Tsakonic on the Peloponnese to this day. Some of the younger dialects, such as Cappadocian , disappeared with the resettlement of the speakers in what is now Greece after 1923, and Cypriot Greek remains a non-literary form of language to this day.

Phonetics and Phonology

It is assumed that most of the developments in modern Greek phonology in Middle Greek were already completed or took place during this language level. These include, above all, the already established dynamic accent , which had already replaced the ancient Greek tone system in Hellenistic times, the vowel system gradually reduced to five phonemes without differentiating the vowel length and the monophthongization of the ancient Greek diphthongs .

Vowels

The Suda , a lexicon from the end of the 10th century, provides information about the sound level of the vowels with its antistoichean order , which lists the terms alphabetically but classifies letters that are pronounced next to each other. So αι and ε, ει, η and ι, ο and ω as well as οι and υ are classified together, so they were homophonic.

| Front | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | ||

| Closed | [ i ] ι , ει , η | [ y ] υ , οι , υι | [ u ] ου |

| Half open | [ ɛ ] ε , αι | [ ɔ ] ο , ω | |

| Open | [ a ] α | ||

Until about 10/11. In the 19th century, υ, οι and υι were pronounced [y] and then became [i]. In the diphthongs αυ, ευ and ηυ , the second component developed early from [u], presumably via [ β ] and [ ɸ ] to [ v ] or [ f ]. Before [n] was υ to [m] ( εὔνοστος Eunostos > ἔμνοστος émnostos , χαύνος cháunos > χάμνος chamnos , ἐλαύνω eláuno > λάμνω Lamno ) or fell away ( θαῦμα thauma > θάμα ThaMa to), before [s] it was occasionally [ p] ( ἀνάπαυση anápausi > ἀνάπαψη anápapsi ).

The apheresis ( ἀφαίρεσις , 'omission' of initial vowels) has led to some new word formations: ἡ ἡμέρα i iméra > ἡ μέρα i méra ('the day'), ἐρωτῶ erotó > ρωτῶ rotó ('ask').

A regular phenomenon is that of synicesis ( συνίζησις , 'summary' of vowels). For many words with the combinations / éa /, / éo /, / ía /, / ío /, the emphasis shifted to the second vowel, and the first became a semi-vowel [j]: Ῥωμαῖος Roméos > Ῥωμιός Romiós ('Romans') , ἐννέα ennéa > ἐννιά enniá ('nine'), ποῖος píos > ποιός piós ('what a, which'), τα παιδία ta pedía > τα παιδιά ta pediá ('the children'). The vowel ο often disappeared from the endings -ιον -ion and -ιος -ios ( σακκίον sakkíon > σακκίν sakkín , χαρτίον chartíon > χαρτίν chartín , κύριος kýrios > κύρις kýrios > κύρις kýrios ).

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sth. | stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | stl. | |

| Plosives | [ p ] π | [ t ] τ | ([ k ]) κ | |||||||||

| Nasals | [ m ] μ | [ n ] ν | [ ŋ ] (1) ( γ ) | |||||||||

| Vibrants | [ r ] ρ | |||||||||||

| Fricatives | [ β ] (2) υ | [ ɸ ] (2) υ | [ v ] β / υ | [ f ] φ / υ | [ ð ] δ | [ θ ] θ | [ z ] ζ , σ | [ s ] σ | [ ç ] (3) χ | ([ γ ]) ( γ ) (4) | [ x ] (3) χ | |

| Approximants | [ l ] λ | [ j ] γ (4) / ι | ||||||||||

Already in late antiquity the change in the consonant system of the voiced Plosiva and was aspirated voiceless Plosiva completed to fricatives. The velar sounds [kʰ] and [g] split into two variants, a palatal before anterior and a velar before [a] and posterior vowels. The breath [h], which was not written in Attic and which had already disappeared in most other dialects in antiquity ('breath silos'), had long since been completely extinguished in the 9th century, when the spiritus asper became mandatory for its identification.

Changes in the phonological system mainly affect consonant compounds that show Sandhi appearances: When combining two plosives or fricatives, there is a tendency to a combination of both: [k] and [p] become [x] and [f] before [t] ] ( νύκτα nýkta > νύχτα nýchta , ἑπτά EPTA > ἑφτά efta ), [θ] is before [f] and [x] and for [s] [t] ( φθόνος fthónos > φτόνος ftónos , παρευθύς parefthýs > παρευτύς pareftýs , χθές chthes > χτές chtes ). The nasals [m] and [n] occasionally disappear before voiceless fricatives: ( νύμφη nýmfi > νύφη nýfi , ἄνθος ánthos > ἄθος áthos ).

Through a similar phenomenon, the vocalization of voiceless plosives after nasals, the Greek later formed the voiced plosives [b], [d] and [g] again. When exactly this development took place is not documented; it seems to have started in Byzantine times. In Byzantine sources the graphemes μπ, ντ and γκ for b, d and g can be found in transcriptions from neighboring languages , such as B. in ντερβίσης dervísis (for Turkish derviş , dervish ').

grammar

Until around 1100, Greek made the decisive change from ancient to modern Greek grammar and has changed only insignificantly since then. What is striking is the absence of numerous grammatical categories inherited from Indo-European, especially in the verb system, as well as the tendency towards more analytical formations and periphrastic verb forms, in the syntax of paratactic sentence structure compared to the often complicated and nested constructions of ancient Greek.

The development of morphology in Middle Greek began in late antiquity and is characterized by a tendency to systematize and unify the morphemes of declination , conjugation and comparison . So the third, ungleichsilbige declination of ancient Greek was at the nouns by forming a new nominative from the oblique regular 1st and 2nd declension case forms adapted: ὁ πατήρ ho pater , τὸν πατέρα ton Patera > ὁ πατέρας o Pateras , accusative τὸν πατέραν ton patéran . Feminine nouns with the endings -ís / -ás formed the nominative corresponding to the accusative -ída / -áda , so ἐλπίς elpís > ἐλπίδα elpída ('hope') and Ἑλλάς Ellás > Ἑλλάδα Elláda ('Greece'). Only a few nouns were excluded from this simplification, such as φῶς fos ('light'), genitive φωτός photos .

The ancient Greek, sometimes irregular, comparative formation of adjectives with the endings -ιον -ion and -ων -ōn gradually gave way to the formation with the suffix -ter and regular adjective endings : μείζων meízōn > μειζότερος mizóteros ('the greater').

From the enclitic genitive form originated the personal pronoun of the first and second or the demonstrative the third person and analog formations unstressed, appended to the noun (enclitic) possessive pronouns μου mou , σου sou , του tou / της tis , μας mas , σας sas , των ton .

In addition to the particles na and thená (see below), the ancient Greek οὐδέν oudén ('nothing') gave rise to the negation particle δέν den ('not').

In the conjugation of verbs, too, exceptions and rare forms were replaced by regular forms through analogistic formations. So the conjugation of the verbs on -μι -mi dwindled in favor of regular forms on -o : χώννυμι chōnnymi > χώνω chóno ('to come across'). The contracted verbs in -aō , -eō etc. with sometimes complicated amalgamations of the conjugation endings take on their endings analogously to the regular forms: ἀγαπᾷ agapâ > ἀγαπάει agapáï ('he loves'). The use of the augment was gradually limited to regular, accentuated forms, the reduplication of the stem gradually became no longer productive (the perfect also formed periphrastically ) and was only retained in frozen forms.

The variety of stem variants of ancient Greek verbs was reduced to mostly two fixed stems for the conjugation of the various aspects , occasionally to a single one. The stem of the verb λαμβάνειν lambánein ('to take') appears in ancient Greek in the variants lamb, lab, lēps, lēph and lēm and is reduced to the forms lamv and lav in Middle Greek .

The auxiliary verb εἰμί eimí ('to be'), for example, took regular passive endings, examples in the indicative singular:

| Present | Past tense | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | εἰμί eimi | > | εἶμαι íme | ἦ ē | > | ἤμην ímin |

| 2nd person | εἶ ei | > | εἶσαι íse | ἦσθα ēstha | > | ἦσοι ísy |

| 3rd person | ἐστίν estin | > | ἔνι éni > ἔναι éne > εἶναι íne | ἦν ēn | > | ἦτο íto |

The numerous forms that have disappeared include the dative , which was replaced in the 10th century by the genitive and the prepositional construction with εἰς is ('in, zu') + accusative, the dual , as well as almost all participles and the imperative forms of the third person . The opt has been through the design by side sets with the conjunctions ὅτι OTi (that ') and ἵνα INA (so') replaced ἵνα was ἱνά iná to να na . From the construction θέλω να thélo na ('I want that ...'), the late Byzantine θενά thená finally formed the modern Greek future particle θα tha , which replaced the old future forms. Ancient formations such as the genitive absolutus , the AcI and almost all of the frequent participle constructions gave way to the use of the newly developed gerund or constructions with subordinate clauses.

Probably the most noticeable change in the grammar compared to ancient Greek is the almost complete elimination of the infinitive , which has been replaced by subordinate clauses with the particle να na . Arabic influences were assumed to explain this phenomenon , since an education like I can, that I can walk was already common in classical standard Arabic. The phenomenon can also be found, possibly mediated by Greek, in the neighboring languages and dialects in the Balkans, namely in Bulgarian and Romanian , which are typologically similar in many respects to Middle and Modern Greek, although they are not genealogically closely related to it are. Balkanology is concerned with research into this Balkan language federation .

vocabulary

Internal language innovations

Many Greek words have undergone a decisive change in meaning in the vicinity of the Eastern Roman Empire and the Christian religion. For example, the term Ῥωμιός Romiós ('Romans') replaced the ancient expression Ἕλλην Héllēn ('Greek'), which was only used for followers, for the Eastern Roman citizen (who defined himself more by belonging to orthodoxy than by linguistic or ethnic affiliation) the old Olympic religion or as a term for the 'pagan' was used. It was not until the 15th century that scholars returned to the ethnic and, above all, linguistic-cultural continuity of Greece and used the term Hellenic again in this sense.

Christian influenced lexicographical changes in the central Greek found, for example in the words ἄγγελος Angelos 'or (' messenger '>' heavenly '>, angels) ἀγάπη Agapi (love'> 'charity' in stricter demarcation to ἔρως Eros , the, physical 'Love).

In everyday words, some ancient Greek tribes were replaced by others. An example of this is the term for 'wine', where the word κρασίον krasíon (roughly 'mixture') replaced οἶνος ínos , which was inherited from ancient Greek . From the word ὄψον ópson with the meaning 'food', 'what one eats with bread', the word ὀψάριον opsárion developed over the suffix -άριον -árion, borrowed from Latin -arium , to the meaning 'fish', which is transferred through apheresis and synizis psárin to modern Greek ψάρι psari was the ancient Greek and ἰχθύς ichthys repressed that as acrostic became for Jesus Christ a Christian symbol.

Loanwords

Middle Greek adopted numerous Latinisms , especially at the beginning of the Byzantine Empire , including titles and other terms from the life of the imperial court such as Αὔγουστος Ávgoustos ('Augustus'), πρίγκηψ prínkips (from Latin princeps , prince'), μάγιστρος mágistros ( mágistros ) , Master '), κοιαίστωρ kiéstor (from Latin. quaestor , Quästor '), ὀφφικιάλος offikiálos (from Latin. officialis officially ').

Even everyday items came from the Latin into Greek one, examples are ὁσπίτιον ospítion (from Latin. Hospitium , hostel '; from modern Greek σπίτι Spiti , house'), σέλλα Sella (saddle), ταβέρνα Taverna (, tavern), κανδήλιον kandílion (from Latin. candela 'candle'), φούρνος foúrnos (from Latin. furnus , oven ') and φλάσκα fláska (from Latin. flasco , wine bottle').

Other influences on Middle Greek resulted from contact with neighboring languages and the languages of the Venetian, Frankish and Arab conquerors. Some of the loanwords from these languages have persisted in Greek or in its dialects:

- κάλτσα káltsa from Italian calza 'stocking'

- ντάμα dáma from French dame 'lady'

- γούνα goúna from Slavic guna 'fur'

- λουλούδι louloúdi from Albanian lule 'flower'

- παζάρι pazári from Turkish pazar (this from Persian), market, bazaar '

- χατζι- chatzi- from Arabic haddschi , Mekkapilger ', as a name addition for a Christian after a Jerusalem pilgrimage

font

The agent used the Greek 24 letters of the Greek alphabet , which until the end of antiquity mainly as Lapidar- and majuscule were used and without spaces between words and diacritics.

Uncials and italics

In the third century, under the influence of the Latin script, the Greek Uncials developed for writing on papyrus with a reed pen , which became the main script for Greek in the Middle Ages. A widespread characteristic of medieval capital letters such as the uncial is a wealth of abbreviations (e.g. ΧϹ for 'Christos') and ligatures .

For the quick scratching of wax tablets with a stylus, the first Greek ' cursive ' was developed, an italic that already showed the first ascenders and descenders as well as letter connections. Some letter forms of the uncials ( ϵ for Ε , Ϲ for Σ , Ѡ for Ω ) were also used as capitals, especially in the sacred area, the sigma in this form was adopted as С in the Cyrillic script . The Greek uncial first used the high point as a sentence separator, but was still written without spaces between words.

Minuscule

From the 9th century onwards, with the introduction of paper , the Greek minuscule script, which probably originated from italics in Syria, appears more and more frequently, which for the first time regularly uses the accents and spiritus developed as early as the 3rd century BC. This very fluid script with excess and descender lengths and many possible letter combinations was the first to use the space between words. The last forms in the 12th century were the iota subscriptum and the final sigma ( ς ). After the Islamic conquest of Greece, the Greek script disappeared in the area of the eastern Mediterranean and was limited to the use by Greek studies in western and central Europe. Developed in the 17th century by a printer from the Antwerp printer dynasty Wetstein, the type for Greek capital letters and lower case letters finally became binding for modern Greek printing.

Text sample

Atticistic Koinē

Anna Komnena , Alexiade , beginning of the first book (around 1148):

- Originaltext:

Ὁ βασιλεὺς Ἀλέξιος καὶ ἐμὸς πατὴρ καὶ πρὸ τοῦ τῶν σκήπτρων ἐπειλῆφθαι τῆς βασιλείας μέγα ὄφελος τῇ βάσιλείᾳ Ῥωμαίων γεγένεται . Ἤρξατο μὲν γὰρ στρατεύειν ἐπὶ Ῥωμανοῦ τοῦ Διογένους. -

Transcription :

O vasilevs Alexios ke emos patir ke pro tou ton skeptron epiliphthe tis vasilias mega ophelos ti vasilia Rhomeon jejenete. Irxato men gar stratevin epi Rhomanou tou Diojenous. -

IPA transcription :

ɔ vasi'lɛfs a'lɛksjɔs kɛ ɛ'mɔs pa'tir kɛ prɔ tu tɔn 'skiptron ɛpi'lifθɛ tis vasi'lias' mɛɣa' ɔfɛlɔs ti vasi'lia rɔ'mɛɔn ʝɛ'ʝɛnɛtɛ. 'irksatɔ mɛn ɣar stra'tɛvin ɛp'i rɔma'nu tu ðiɔ'ʝɛnus - Translation:

The Emperor Alexios, who was my father, was of great use to the Roman Empire even before he was made imperial. He began as a military leader under the emperor of Romanos Diogenes.

Vernacular

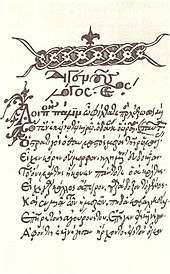

From the Digenis Akritas , Madrid manuscript, 12th century.

- Original text:

Καὶ ὁ ἀμιρὰς ὡς τὸ ἤκουσεν, μακρέα τὸν ἀποξέβην,

ἔριψεν τὸ κοντάριν του καὶ δάκτυλον τοῦ δείχνει

καὶ μετὰ τοῦ δακτύλου του τοιοῦτον λόγον λέγει:

"ζῆς Νὰ, καλὲ νεώτερε, ἐδικόν σου ἔναι τὸ νίκος."

- Transcription:

Ke o amiras os to ikousen, makrea ton apoxevin,

eripsen to kontarin tou ke daktilon tou dichni

ke meta tou daktilou tou tiouton logon legi:

«Na zis, kale neotere, edikon sou ene to nikos.»

kɛ ɔ ami'ras ɔs tɔ 'ikusɛn, ma'krɛa tɔn apɔ'ksɛvin

' ɛripsɛn tɔ kɔn'tarin tu kɛ 'ðaktilɔn tu' ðixni

kɛ mɛ'ta tu ðak'tilu tu ti'utɔn 'lɔɣɔn' lɛʝi

na z 'lɛ nɛ'ɔtɛrɛ, ɛði'kɔn su' ɛnɛ tɔ 'nikɔs

- Translation:

And when the emir heard it, he withdrew a little,

threw away his spear and showed him his finger,

and with this hint he spoke this word:

"You shall live, good young man, the victory is yours."

Effect on other languages

As the language of the Orthodox Church , especially with the Slavic mission of the brothers Kyrill and Method , Middle Greek has found its way into Slavic languages in the religious area , especially into Old Church Slavonic and, via its successor varieties, the various Church Slavonic editors, also into the languages of the countries with an Orthodox population, mainly Bulgarian , Russian , Ukrainian and Serbian . This is why Greek loanwords and neologisms in these languages often correspond to Byzantine phonology, while they came to the languages of Western Europe via Latin mediation in the sound form of classical Greek (compare German automobile with Russian автомобиль awtomobil and the corresponding differences in Serbo-Croatian - Croatia with a Catholic history , Serbia with Serbian Orthodox).

Some German words, especially from the religious field, have also been borrowed from Middle Greek. These include church (from κυρικόν kirikón 'house of God' [proven in the 4th century], a vulgar form of κυριακόν kȳriakón , neuter singular to κυριακός kȳriakós “belonging to the Lord”; of which the feminine form κύρικη is to be added and kíilrica [presumably to be added to basilica ] Old High German kirihha ) and Pentecost (from πεντηκοστή [ἡμέρα] pentikostí [iméra] , the fiftieth [day, scil . after Easter] '; borrowed either from late Latin pentecoste or Gothic paíntēkustēn ; thereof Old High German fimfim ).

research

In the Byzantine Empire, ancient and Middle Greek texts were copied many times, and the study of these texts was part of Byzantine education. Several collections of transcripts attempted to comprehensively document Greek literature since ancient times. After the fall of Eastern Rome, many scholars and a large number of manuscripts came to Italy, with whose scholars there had been a lively exchange since the 14th century. The Italian and Greek humanists of the Renaissance put on important collections in Rome, Florence and Venice. The teaching of Greek by Greek contemporaries also brought about the Itazist tradition of Italian Greek.

In the 16th century, through the mediation of scholars who had studied at Italian universities, the Graecist tradition began in Western and Central Europe, which included the Byzantine works, which mainly included classical philology, history and theology, but not Middle Greek language and literature the main subject of research. Hieronymus Wolf (1516–1580) is considered to be the 'father' of German Byzantine Studies. In France, Charles Dufresne Du Cange (1610–1688) was the first important Byzantinist. In the 18th century, interest in Byzantine research decreased significantly - the Enlightenment saw in Byzantium primarily the decadent, declining culture of the end times of the empire.

It was not until the 19th century that the publication and research of Middle Greek sources increased rapidly , not least because of philhellenism . The first vernacular texts were also edited. Gradually, Byzantinology began to break away from Classical Philology and to become an independent field of research. The Bavarian scientist Karl Krumbacher (1856–1909), who was also able to conduct research in the now founded state of Greece, is considered the founder of Middle and Modern Greek philology. From 1897 he held a chair in Munich. Also in the 19th century, the Russian Byzantinology emerged from the church-historical connection to the Byzantine Empire.

For the state of Greece, which was re-established in 1832, Byzantine research was of great importance, as the young state tried to rediscover its cultural identification in the ancient and orthodox-medieval tradition. The later Greek Prime Minister Spyridon Lambros (1851-1919) founded Greek Byzantinology, which was continued by his and Krumbacher's students.

Byzantinology also plays an outstanding role in the other countries of the Balkan Peninsula, as the Byzantine sources are often significant for the history of their own people. There is a longer tradition of research, for example, in Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary. Further centers of Byzantinology are located in the USA, Great Britain, France and Italy. In the German-speaking countries, the Institute for Byzantine Studies, Byzantine Art History and Neo-Greek Studies at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich and the Institute for Byzantine and Neo-Greek Studies at the University of Vienna are the most important. The Association Internationale des Études Byzantines (AIEB), with its registered office in Paris , acts as the international umbrella organization for Byzantine Studies.

literature

- Grammar and dictionary

- David Holton , Geoffrey Horrocks , Marjolijne Janssen , Tina Lendari, Io Manolessou, Notis Toufexis : The Cambridge Grammar of Medieval and Early Modern Greek . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2019, CUP website .

- Emmanouil Kriaras : Λεξικό της μεσαιωνικής ελληνικής δημώδους γραμματείας . 12 volumes. Thessaloniki 1968-1993.

- Studies

- Hans-Georg Beck : Church and theological literature in the Byzantine Empire. Munich 1959.

- Robert Browning : Medieval and Modern Greek. Hutchinson, London 1969 (2nd edition. Published: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 1983, ISBN 0-521-23488-3 ), review by H.-P. Drögemüller in Gymnasium 93 (1986) 184ff.

- Anthony Cutler, Jean-Michel Spieser: Medieval Byzantium. 725-1204. Beck, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-406-41244-0 ( Universum der Kunst 41).

- Herbert Hunger : The high-level profane literature of the Byzantines. 2 vol., Munich 1978.

- EM Jeffreys , Michael J. Jeffreys: Popular literature in late Byzantium. Variorum Reprints, London 1983, ISBN 0-86078-118-6 ( Collected Studies Series 170).

- Christos Karvounis : Greek. In: Miloš Okuka (Ed.): Lexicon of the Languages of the European East. Wieser, Klagenfurt et al. 2002, ISBN 3-85129-510-2 ( Wieser Encyclopedia of the European East 10), ( PDF; 977 kB ).

- Karl Krumbacher : History of Byzantine literature from Justinian to the end of the Eastern Roman Empire (527–1453). 2nd Edition. Beck, Munich 1897 ( Handbook of Classical Antiquity Science. Volume 9. Dept. 1), (Reprint. Burt Franklin, New York NY 1970, ( Bibliography and Reference Series 13)).

- Theodore Markopoulos: The Future in Greek. From Ancient to Medieval . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2009.

- Gyula Moravcsik: Introduction to Byzantinology. Translated from the Hungarian by Géza Engl. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1976, ISBN 3-534-05670-1 ( The Ancient Studies ).

- Heinz F. Wendt: The Fischer Lexicon. Languages. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 3-596-24561-3 ( Fischertaschenbuch 4561).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ PDF (407 kB) History of the Scriptures ( Memento from December 15, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Károly Földes-Papp: From the rock painting to the alphabet. The history of writing from its earliest preliminary stages to modern Latin script . Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-7630-1266-4 .

- ↑ Anna Komnena, Alexiade , Book 1: Αλεξιάς, Βιβλίο 1 (Wikisource)

- ^ David Ricks : Byzantine Heroic Poetry. Bristol 1990, ISBN 1-85399-124-4 .

- ↑ Church. In: Digital dictionary of the German language . The assumption that the Gothic played a role here is explained: “It is unlikely that the Got [ische] Greek [isch] kȳrikón conveyed the other Germ [anic] languages, instead the word is taken up in Greek [isch] -lat [einisch] shaped Christianity of the Roman colonial cities (e.g. Metz, Trier, Cologne) within the framework of the building activity of the Constantinian era . "

- ^ Pentecost. In: Digital dictionary of the German language .

- ^ Paul Meinrad Strässle: Byzantine Studies - an interdisciplinary challenge not only for historians ( Memento of April 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive ).