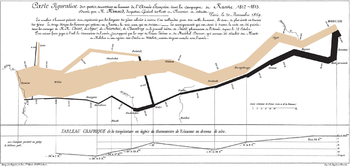

Russian campaign in 1812

Mir - Mogilev - Ostrovno - Kobrin - Klyastitsy - Gorodeczno - Smolensk - Polotsk I - Walutino - Borodino - Tschirikovo - Tarutino - Maloyaroslavets - Polotsk II - Vyazma - Lyachovo - Chaschniki - Smoljany - Krasnoi - Beresina

Napoleon's Russian campaign of 1812 (in French Campagne de Russie , in Russian also called the Patriotic War - Отечественная война, Otečestvennaja vojna -) represents the first phase of the Sixth Coalition War in which France and Russia faced each other with their respective allies. After initial French successes, the campaign ended in one of the greatest military disasters in history. After the Grande Armée had been completely expelled from Russian territory, the campaign culminated in the second phase of the war at the beginning of 1813: In the wars of liberation , first Prussia , then Austria and later the French-dominated German Rhine Confederation states passed over to the anti-Napoleonic side, which defeated France in 1814 and went to Napoleon Forced abdication .

Political history

Before the Russian campaign, France had been at war almost continuously for 19 years. Through the Peace of Tilsit , Napoleon Bonaparte and the Russian Tsar Alexander I became allies in July 1807. A connection to the royal family planned by Napoleon through her marriage to Katharina Pawlowna , a sister of Alexander, was prevented by her marriage to Prince Georg von Oldenburg in 1809 . Her younger sister Anna , who Napoleon suggested as an alternative, was only 15 years old, which is why he was put off until a later date. This news only reached Napoleon when he had already decided on Marie-Louise von Habsburg , a daughter of the Austrian emperor. Since it was not uncommon at the time to marry fifteen-year-olds, Napoleon saw this as a rejection. In fact, the Tsar 's mother did not like Napoleon and did not want any of her daughters to marry him.

In 1809 a war broke out between France and Austria. At the same time there were uprisings in Tyrol , Prussia and the Kingdom of Westphalia . As an ally of France, Russia intervened in Austria's campaign against the Duchy of Warsaw . But the Russian army only waged a sham campaign in which there was no battle with the Austrians. Good contacts also continued to exist with Prussia, with which Russia was allied until 1807. There was a close friendship between Alexander I and the Prussian queen. To the displeasure of Napoleon, the Tsar received the Prussian royal couple in January 1808 for a friendship visit of several weeks in Saint Petersburg .

In 1810 Napoleon relaxed the continental blockade against Great Britain , with which it had been at war for French ships since 1793 , apart from a one-year hiatus due to the Peace of Amiens . French merchants were allowed to trade with Great Britain again under certain conditions. On the other hand, in October he demanded from the tsar that even neutral ships that wanted to call at Russian ports should be confiscated if they had goods of English origin on board. In August Alexander I learned that three French divisions were to be relocated from southern Germany near the Russian border. 50,000 new rifles had arrived in Warsaw for the Polish brigades . At the end of the year France annexed the Duchy of Oldenburg and attacked the tsar's brother-in-law. Alexander I no longer took part in the continental blockade, which had become an economic burden. Russia could no raw materials such as wood, flax or pitch to the UK export . Textiles, coffee, tea, tobacco or sugar were not allowed to be imported from Great Britain . The tax revenue from these businesses was missing from the state treasury, but smugglers made big profits. Companies dependent on imports or exports had gone bankrupt . The value of the rubble had fallen dramatically. Due to the negative trade balance , the tsar banned the import of luxury goods on December 31st. This particularly affected France, which exported large quantities of silk, wine and perfume to Russia. Other goods were subject to such high tariffs that they were hardly ever imported. This only applied to goods that came to Russia by land. Imports made by sea were duty-free. This benefited the English and the neutral states, whose ships carried a large part of English goods. Russia occupied large parts of the former Kingdom of Poland. These areas have traditionally been important suppliers of timber for the construction of British war and merchant ships. Since Russia had occupied wooded Finland , it was the largest supplier of wood in Europe and vital to British shipbuilding.

In 1811 France and Russia began preparations for war. In February five additional Russian divisions were relocated to the border with Poland, and the troops at the border were reinforced with 180 cannons. The armaments factories in Tula and Alexandrowsk were instructed to work even on high holidays. The tsar expected an invasion and also thought of a war of aggression . For this he needed the support of Poland, Prussia and Austria. On February 12th, he wrote to Adam Czartoryski and suggested that he proclaim a Kingdom of Poland. In return, the most important politicians and military officials in the Duchy of Warsaw should guarantee him in writing that they would support him. At the end of February he wrote to the Prussian king and the Austrian emperor, sharing some of his plans with them. Napoleon found out about this and put his army on alert. Both sides assured several times that they did not want a war. The Russian military attaché Alexander Ivanovich Tschernyschow traveled several times from Saint Petersburg to Paris for negotiations. In April he wrote from Paris that, in his opinion, the war was a done deal for Napoleon. Statements to the contrary were only intended to buy time. Prince Alexander Kurakin , the Russian envoy in Paris, had to listen to a loud speech by Napoleon on August 15, at a reception for Napoleon's birthday, in which he claimed that Russia was planning a war. On October 17, Gerhard von Scharnhorst signed an alliance treaty between Prussia and Russia in Saint Petersburg, which remained meaningless as it only applied in the event of a French attack on Prussia. In this case, the Prussian army should withdraw to Russian territory in order to unite with the Russian army there.

In November Napoleon requested topographical maps of Russia from the imperial library, and Lithuania was of particular interest to him. In December, he informed his allies that they should prepare for war. At the end of 1811, a printer who was making Russian banknotes was arrested in Paris. He allegedly did so on behalf of the French Police Minister and was released. Louis-Philippe de Ségur , a close confidante of Napoleon, confirmed the arrest. According to his account, Napoleon saw the counterfeit money only with clear reluctance and most of the money was burned on the retreat in Vilna on Napoleon's instructions. Ségur didn't say anything about the rest of the story. Scharnhorst traveled to Vienna on behalf of the Prussian king to conduct exploratory talks there. On December 26th, the Austrian Chancellor Metternich rejected an alliance.

Napoleon was well aware of the peculiarities of the theater of war and the measures to be derived from it. The “stumbling into” the “Russian risk” - as often found in literature - definitely did not take place. He was aware of the experiences during the winter campaign of 1806/07 east of the Vistula and in Poland; furthermore, as early as the spring of 1811, he supplied himself with the most important literary works on the campaigns of the Russians and Austrians; as well as representations of the operations of Charles XII. against Russia in the Great Northern War in 1708/09. In addition, immediately before the conflict, Polish and French officers were commissioned to investigate the road conditions on the other side of the Njemen (German: Memel) .

In February 1812 French troops occupied Swedish Western Pomerania and the then Swedish island of Rügen . An employee of the Paris War Ministry who had regularly sold information to Chernyshev was arrested that same month. Napoleon also had his spies. In this way he came into possession of Russian printing plates for maps. In March, the Vossische Zeitung reported in Berlin on the deployment of French troops in Germany. John Quincy Adams , American envoy in Saint Petersburg and later President of the USA , noted the departure of Russian troops from Saint Petersburg in his diary at the same time. On April 5, Sweden signed an alliance with Russia in which it renounced Russia-occupied Finland. In return, it was to receive Norway, which belonged to Denmark, after a victory against Napoleon. On April 8, Alexander I demanded the withdrawal of all French troops as a precondition for further negotiations. This letter was delivered in Paris on April 30th. As early as April 18, Napoleon had made a peace proposal to England, which was rejected because the offer provided that Napoleon's brother Joseph should remain King of Spain. On April 21, Alexander left Saint Petersburg and traveled to Vilnius to take command of the army. In Lithuania , a news blackout was previously imposed. Countess Tiesenhausen, who lives in Vilnius, wrote: “We didn't even know that the French were marching through Germany […].” On May 9th, Napoleon left Paris. Louis de Narbonne presented Alexander a letter from Napoleon on May 18, in which he confirmed his readiness for peace. In return, he demanded that Russia take part in the continental blockade again. Narbonne also reported to Alexander the strength of the Grande Armée, doing so on the express orders of Napoleon. Alexander was not impressed. When Narbonne handed over a letter of reply to Napoleon six days later, he said: “So all the mediation proposals have come to an end! The spirit that prevails in the Russian camp drives us to war. […] There is no time to waste in fruitless negotiations […]. ”With the Peace of Bucharest , Russia ended the war with the Ottoman Empire on May 28th, which freed up more troops for a war against Napoleon. According to the treaties with Sweden and the Ottoman Empire, 90,000 Russian soldiers marched as reinforcements towards the Russian-Polish border. The Russian envoy in Paris, Kurakin, had repeatedly asked for his passports to leave. From Napoleon's point of view, this was a break in diplomatic relations, which years later he represented as a Russian declaration of war. Kurakin received his passports on June 12 and left Paris. On June 22nd, Napoleon wrote a daily order in Wilkowiszki , in which he proclaimed the Second Polish War . The next day Napoleon rode to the Nyemen, camouflaged in the coat of a Polish Uhlan . He was accompanied by Armand de Caulaincourt , who reported that Napoleon's horse shied away from a hare jumping up and the emperor fell from his horse. The war started on a bad omen, said Caulaincourt.

logistics

In previous wars, the French army had almost exclusively supplied itself from the country it passed through. Most of the time, like Napoleon's troops later, French revolutionary troops did not have a militarily organized train like other armies and were therefore faster and more agile, but dependent on constant supplies from the peasants and merchants of the occupied country. This strategy had worked well in densely populated Central Europe, but in the vast expanses of Russia, with its sparsely populated areas and poor road network, this method was doomed to failure. For the war against Russia, Emperor Napoleon had more extensive logistics than previously planned, and many warehouses in Prussia and Poland were filled with supplies. A large number of barges were used on the rivers in Prussia and Poland to take over the supplies by water. The time for the invasion was also determined from a logistical point of view. Napoleon assumed that the army could get Russian grain supplies at this time of year, and there should be enough forage for horses and cattle. The medical care was exemplary for the time. The French army was one of the first to have medical carts. The doctor Dominique Jean Larrey , who introduced the mobile hospitals, accompanied the army in Russia as head of the medical corps.

Due to this claim, the entourage that followed the Great Army was very large. Napoleon's personal entourage alone consisted of 18 supply wagons, a cloakroom wagon, two butlers, three cooks, six servants and eight grooms. He himself drove in a six-horse carriage, another 52 carriages were needed for his staff alone and an enormous number of wagons just for supplying them. For the construction of bridges, pontoons and carts with materials and tools for pioneers were carried on several wagons . Field blacksmiths and a mobile printer were part of the entourage. The artillery had more than 3,000 wagons with only their gun mounts and the associated ammunition wagons. Tailors, shoemakers and other craftsmen accompanied the army. The troops were accompanied by more than 50 cash vans with money for the soldiers' pay and other expenses. Each staff in each corps had a huge fleet of vehicles, including many vehicles for the personal comfort of the senior officers. Often the carts that were important for supplying the army were hindered by this. The doctor Heinrich von Roos reported that when he reached Vilna, his ambulance vehicles had not even crossed the Nyemen .

In addition to the fleet of vehicles that the associations already had, Napoleon had 26 equipage battalions with over 6,000 vehicles available for military transport . Behind the army, herds of slaughter cattle were to follow, which, driven forward without pause, quickly became emaciated and, to a large extent, perished at the roadside. In addition, some of the 26 Equipage battalions were drawn by oxen, which were intended for later consumption; these animals perished after a short time due to insufficient care. The wagons of the 26 Equipage battalions, which together had a transport capacity of barely 8,000 tons, were sufficient to supply the approximately 600,000 men of the Grande Armée (the occupation troops in Prussia and Poland as well as the numerous military officials who followed the army also had to be fed are not remotely off. Therefore , the French units - just like the "revolutionary troops" before them - requisitioned innumerable horse-drawn vehicles in Prussia, Poland and Lithuania. According to an official report by the government in Königsberg, in 1812 the French army formally requisitioned 1,629 carts and 7,546 horses in the Prussian province of East Prussia alone. In addition, the passing troops of the Grande Armée from the province forcibly took another 26,579 wagons and 79,161 horses. Similar numbers have been reported from the other Prussian provinces and the Duchy of Warsaw. The Marquis de Chambray described these countless private wagons, which accompanied the troops without order, as "a real nuisance", as they constantly blocked the streets and thereby tore the marching units apart. The horses and people forced to come along by the army had to look after themselves as they did not belong to the army. They were ruthlessly exploited for a short time, so that many of them perished miserably and never returned home. The Grand Army was spread over an area of around 350,000 square kilometers at the end of August. From the well-stocked large magazines in Gdansk , the carts only had to cover more than 900 kilometers as far as Smolensk. A transport battalion (there and back) needed more than 80 days for this route. Therefore, in January and February 1813, many of the French magazines in Prussia, Poland, or Lithuania were still filled with food, clothing, medicines, and other necessities when they were captured by Russian and Prussian troops, while many French soldiers were starving to death. In Vilnius alone, the Russian troops captured 4 million portions of bread and rusks, 3.6 million portions of meat and 9 million portions of brandy, wine and beer as well as several 1,000 tons of clothing and other military supplies. In Minsk, despite attempts to burn them when the city was occupied, they stole 2 million servings of bread and rusks. The claim of the Grande Armée to be “faster and more agile” than other armies meant that the militarily completely disorganized entourage could not follow the combat units from the start, so that many units were already hungry before the Nyemen crossed or Grodno were reached. Therefore, from the beginning, many soldiers were looking for something to eat and drink. It was not uncommon for them to leave their unit to look for food in remote villages (as numerous diaries and letters from soldiers show). Not least because of this, the Grande Armée lost around 50,000 soldiers by deserting in the first six weeks.

The units had carts for groceries, but no carts for feeding the 150,000 horses. The animals, who worked hard every day and therefore had an increased energy requirement, were largely dependent on the green forage that they could graze at night. Therefore, about 10,000 horses were already lying on the way to Vilnius. By the time the Battle of Smolensk took place, tens of thousands of horses died. Despite the forced requisitioning of horses on the way, a large part of the French cavalry had to walk on the retreat from Moscow in order to be able to harness wagons and artillery. Nevertheless, after a short time, numerous ammunition wagons and cannons had to be burned or left standing due to the lack of draft animals. The same applies to the temporary transport trolleys for the sick and wounded.

The logistics of the “Great Army” of 1812 were therefore designed for a very short campaign at most. The “revolutionary” system based on requisitions was already inadequate in Poland and Lithuania in view of the sparsely populated country; it finally failed when the army on the Dnieper (shortly before Smolensk ) crossed the border to (“old”) Russia and from there found almost only abandoned villages and large forests. Since the Grande Armée did not have tents for the soldiers, they had to bivouac in the open air even in the snowstorm and freezing frost. The extensive renunciation of a militarily organized train took revenge in Russia. As a result, the invaders lost significantly more people to hunger, disease and desertion than to enemy action.

The armies

The Grande Armée

Composition and troops of the allies

The Grande Armée was not even in the campaign against Russia halfway out the French. According to today's understanding, even these were to a large extent Italian, German, Dutch, Belgians or Croatians, because France had annexed large parts of Italy , the Netherlands , the German areas west of the Rhine including what would later become Belgium and large parts of northern Germany as far as Lübeck and Dalmatian areas . In addition, the Vistula region from Poland and other individual Polish units, an Irish and a Portuguese legion and a North African cavalry as well as several regiments forcibly recruited in Spain in 1807 served voluntarily in the French army from 1796 .

The states of the Rhine Confederation raised their entire armed forces with around 120,000 soldiers for the campaign against Russia, including more than 30,000 men from the Kingdom of Bavaria , over 27,000 men from the Kingdom of Westphalia and 20,000 from Saxony . These states had their own corps , which were commanded by French generals, while the contingents of the smaller Rhine Confederation members were integrated into the French army.

The Poles in the Duchy of Warsaw saw the Russian campaign as an opportunity to restore Poland by recapturing the areas annexed by Russia . After France and the Confederation of the Rhine, the duchy provided the third largest share of the Grande Armée with 96,000 men in a national show of strength. In the first weeks of the war, Napoleon established other Polish and Lithuanian associations in the conquered areas. Together with those in the French army and in the newly formed associations of the Duchy since the beginning of 1813, around 100,000 Poles fought for Napoleon in the Sixth Coalition War. Troops from the Napoleonic satellite states, Kingdom of Italy and Switzerland , were also deployed in Russia for Napoleon.

Under political pressure Austria and Prussia had to undertake to provide auxiliary corps for Napoleon. Austria had undertaken to provide an army corps of 30,000 men, about a fifth of its armed forces, and Prussia had to deploy almost half of its mobile armed forces with 20,000 men. In contrast to the Austrian corps, whose commander, Prince Schwarzenberg , was directly subordinate to Napoleon, the Prussian contingent was integrated as a division into the corps of French Marshal MacDonald (10th Army Corps). The combat value of these two corps, which had fought against France a few years earlier, was not very great. The motivation to fight for Napoleon against a former ally was lacking. After Prussia had undertaken to provide an auxiliary corps, the Prussian king wrote to the Russian tsar: “Complain about me, but do not condemn me. Perhaps the time will soon come when we will act in close alliance. ”The Russian envoy in Vienna, Count Stakelberg, reported to Saint Petersburg that the deployment of the Austrian corps would be limited to what was necessary.

Napoleon was also at war in Spain, where 250,000 soldiers fought on the French side. After a regiment from Nassau had defected to the enemy there, he viewed some troops of the Rhine Confederation with suspicion. In Braunschweig at the beginning of 1812 there were clashes between French and Westphalian soldiers in which several French were killed or wounded. The situation escalated and there were real street battles. Two Westphalian soldiers were sentenced and shot . A citizen of the city was beheaded . He had nothing to do with the actual incident, he had previously killed a French officer. Instead of being beheaded in Wolfenbüttel as planned , he was demonstratively beheaded in Braunschweig. Napoleon's mistrust was not unjustified. Saxony, Bavaria and Prussia had to surrender cavalry to the main army, which weakened the corps in which their main forces were located. Not only militarily, but also logistically, as the cavalry had a much larger radius of action when requisitioning food. The cavalry of all corps, including the guard, had about 95,000 horses. There were also draft horses for the artillery and the train. When the army marched into Russia, the army had a total of almost 200,000 horses. The quality of the French cavalry horses was often inferior to that of the Russian ones. During the French Revolution, the nobility was expropriated and the breeding studs were closed. Many horses were also killed in the wars that followed.

On the strength of the French "Grande Armée"

Since the inventory lists of the Grande Armée, the letters and dispatches from Emperor Napoleon and the French headquarters were published several times, the structure and strength of the Grande Armée of 1812 has been largely clarified. As the strength of the units, as can be clearly seen in the weekly inventory lists of the Great Headquarters, changed practically daily due to departures and newcomers, the figures are rounded off here in the short summary. According to the inventory lists, the field army with which Emperor Napoleon crossed the Russian border on June 24, 1812, was a little over 420,000 strong. It consisted of the Great Headquarters, the 1st to 8th and 10th Army Corps, the cavalry reserve (with a little over 40,000 riders) with the 1st to 4th Cavalry Corps and the Imperial Guard (the strength of an army corps). Together with the Austrian auxiliary corps of 30,000 men and the associated "large parks", the large army fleets of artillery, trains (supplies) and genius troops (pioneers), with all the associated support troops over 22,000 men, the First line army about 475,000 men and nearly 200,000 horses.

Behind this army followed more support and supply troops, which included a siege park (planned for Riga ) and other bridge trains. These troops also included the directorates, the field justice, the field post offices, the gendarmerie and various craft companies as well as the newly recruited troops in Lithuania (primarily deserters from the Russian army). Together these troops numbered around 35,000 to 40,000 men. This was followed over the course of the next few weeks by the troops of the second and third lines: the 9th and 11th Army Corps, which - together with replacement troops from home at the same time - were around 95,000 to 100,000 strong. Their main task was to secure the long supply routes for the front troops and to set up new magazines in the occupied territories and to protect them against possible attacks. This adds up to an army totaling more than 610,000 men. This number does not include the remaining rear troops and the fortress garrisons in northern Germany, Prussia, Danzig and Warsaw (about 70,000 men). Numbers that deviate from this, which can be found in the literature, are mostly explained by the fact that in some brief descriptions of the campaign the extensive auxiliary and supply troops are wholly or partially passed over with silence or are merely hinted at without further numerical information in a subordinate clause.

By mid-December 1812, several units of the advancing 11th Army Corps "only" reached East Prussia and the Duchy of Warsaw. Since these troops did not cross the Russian border, they are not counted in some depictions of the campaign. Apart from the fact that these troops were undisputedly part of the "Grande Armée", in December 1812 they took over the cover of the soldiers who had returned via the Beresina and thus secured the remnants of the defeated army together with the crews of the fortresses in Prussia and Warsaw who had also stayed behind the advancing Russian army and enabled them to regroup and reorganize as a makeshift. Just because they temporarily stopped the advance of the Russian army from mid-December 1812, which then dragged them into the vortex of doom, they became participants in the Russian campaign.

The Russian Army

The strength of the Russian army should be 600,000 men, for which the tsar paid. In fact, there were only about 420,000 men at the start of the war. That was not unusual for the time, in 1806 Prussia had 250,000 soldiers on paper and initially only got 120,000 together. Due to the size of the Russian Empire, the 420,000 soldiers were spread over a wide area. In many respects the army was behind other armies, so foreign officers were gladly accepted. German, Austrian, Swedish and French officers served in the Russian army. When Alexander I demanded that Napoleon should dismiss the Poles in his guard, he countered that the Tsar should first dismiss the many French in his army. As Napoleon's only serious opponent, Russia was a reservoir for many of his opponents. General Langeron , a Frenchman, had fought in the Russian army for years. The high proportion of foreign officers was not welcomed by everyone because they were often better paid and hired with a higher rank.

The common soldiers were Russians and men from the areas occupied by Russia. In terms of communication, the Russian army had an advantage over the Grande Armée, in which many different languages were spoken and there were disputes between the individual nationalities. In the hope of deserters, the Russian-German Legion was formed. 10,000 copies of an appeal to join the Legion were smuggled into Germany and into German troops. That did not bring the desired success. Since Prussia was occupied by France, the Prussians were viewed as one of the morally weakest points of the Grande Armée. For this reason, former Prussian officers who were in Russian service tried to convince the soldiers at the front to defend themselves; Lieutenant Colonel Tiedemann was shot dead. As early as July 1812, 30 men from the second Guard Uhlan Regiment, consisting of Dutch, joined the legion. This was followed by 50 Prussian infantrymen and 40 hussars who had been captured in the Riga area. On August 22nd, after the battle near Dahlenkirchen, a Prussian hunter battalion defected almost completely. Overall, the Legion was meaningless in 1812 and was not used until 1813.

The Russian Army is often associated with two things - the planned retreat strategy and the scorched earth tactics . There was neither one nor the other. The withdrawal was born out of necessity, according to Carl von Clausewitz “the war was made like this”. Although there were corresponding considerations and suggestions, Clausewitz denied that it was planned in this form.

This contradicts the description of Caulaincourt , the French ambassador at the court of the tsars, which he wrote down on June 5, 1811 after his return from St. Petersburg after a five-hour report to Napoleon on the same evening:

“ If the gun luck should be against me , Alexander had said, I would rather retreat to Kamchatka than cede provinces and sign a treaty in my capital that would only be a truce. The French are brave; but long hardship and a harsh climate discourage him. Our climate, our winter will fight for us. With you miracles only happen where the emperor stands. He can't be everywhere, he can't stay away from Paris for years! Alexander had said that he was only too aware of Napoleon's talent for winning battles and would therefore avoid fighting the French where they were under his command. With reference to the 'guerrilla' in Spain, he said that the entire Russian nation would resist an invasion. "

At the beginning of the war the Russian army was spread over a broad front and too weak against the Grande Armée. As for the scorched earth tactics, there are no reports of major fires as far as Smolensk, and Smolensk was caught on fire mainly from the battle itself. Vilna, Minsk and Vitebsk fell largely unscathed into the hands of the French, like many other places. The Russian army burned its own supplies that they could not take with them. The civilian population's supplies were not burned or their homes. That only happened after Napoleon left Smolensk, and here it cannot be ruled out that some fires were caused by the French army. There are reports that soldiers looted houses that must have been intact in the case. The reports of burnt villages often come from soldiers in the French rearguard, who blamed the Russians for them. Shortly before Moscow, the city of Mozhaisk fell almost undamaged into the hands of the French army, which set up their hospital and garrison there. Wounded Russian soldiers who were in the houses were thrown into the street.

The advance

The invasion of the Grande Armée

On the night of June 24, 1812, Emperor Napoleon ordered the construction of three ship bridges near Kovno (Kaunas) and the passage of his Grande Armée over the Nyemen. At the same time he crossed the border and opened the attack on Russia. In the next few days up to June 30th, an army of around 475,000 men followed (including the Austrian auxiliary corps and the "Great Parks"; see above on the strength of the French "Grande Armée" ). The emperor expected a quick victory, his strategic goal was to put the main Russian armed forces into battle and to destroy them as soon as possible, so his troops followed the Russian armed forces in forced marches. The chasing had catastrophic results:

Immediately after the invasion, thunderstorms began that lasted days, turning the land into swamp and morass. While trying to cross the swollen Wilia , most of the soldiers of a Polish cavalry squadron drowned. The army moved further and further away from their supply wagons, which got stuck in the mud. The Saxon general Ferdinand von Funck reported that more than 1200 farm wagons were used to carry bread for four to five days. Even so, the soldiers went hungry because the bread did not reach them. Every soldier had an emergency ration of biscuits with them, but it was strictly forbidden to attack them. The sparsely populated country could not feed the bulk of the army, and the Russian army had already supplied itself from the country. Due to unclean water, drawn from rivers and swamps, many soldiers fell ill with dysentery . The brandy, which was usually used to make the water drinkable, had run out. Ferdinand von Funck wrote: “The dysentery literally raged among the regiments and when we stopped on the way, the side had to be determined according to the wind, according to which the people should step up to satisfy natural needs, because the air pollutes almost in a few minutes Thousands of soldiers died of illness or exhaustion in the first few weeks, many deserted and some soldiers committed suicide in their desperation. Deserters who were recaptured were mostly shot. Others marched through the country in small or large gangs and terrorized the population. The losses of horses were enormous, more than 20,000 died in the first few days. The feeding situation for the huge number of horses was dramatic. The straw was fed from the roofs of the houses if they had not yet burned down. Hay and oats were rare, unripe grain led to disease and the constant advance did not provide sufficient rest for the horses.

Letters from the soldiers quickly made these conditions known in Germany, which led to concern. As early as August 2nd, King Friedrich von Württemberg therefore forbade his soldiers who were in Russia from spreading bad news at home: “The very highest of all, therefore, want to have seriously forbidden any further written utterance of this kind with the serious addition that if such things should take place again, the authors are to be punished with the most severe punishments ”.

Tsar Alexander I had been in the Russian army since the end of April and was in command. He had little military experience and trusted his advisors, such as the Prussian general Karl Ludwig von Phull . The 1st Russian Western Army under Barclay de Tolly was numerically far inferior to the French, it consisted of about 118,000 men. You faced more than three times the superiority. More than 150 km to the south, the 2nd Western Army was under Bagration with 35,000 men. The reserve army of Alexander Tormassow with 30-35,000 men was still further south and could not intervene in the fight against Napoleon's main army for the time being. To the east of her were the huge Pripjet swamps , which made retreat in that direction impossible. It was only faced by the Austrian auxiliary corps in the Brest-Litovsk area. Napoleon reinforced it with the 7th Corps, which consisted of Saxon troops. The army of Chichagov , which was returning from the war against the Ottoman Empire, was still a long way off, as were reinforcements from Finland under General Steinheil . Barclay de Tolly and Bagration had to retire. The first battle between Russian and French troops took place near Deweltowo on June 28th. During a heavy thunderstorm, Napoleon entered Vilna that afternoon. A week later, on July 5th, the first artillery duel took place on the Daugava, three days later Marshal Davout occupied Minsk.

General von Phull did not retreat quickly enough; several times he sent Lieutenant Colonel Clausewitz to Barclay de Tolly to persuade him to retreat more quickly. He feared that Napoleon would be in Drissa before the Russian army. There Russia had already started building positions months earlier and the army wanted to face battle according to Phull's plan. At the same time, Bagration was to take the offensive behind Napoleon's army. When the army arrived in Drissa, the prepared terrain proved unsuitable. It was located directly on the Daugava, which was not very deep at this point. Parts of the French army could have stabbed the Russian army in the rear after bypassing them. There were no bridges, which is why the cannons should have been left behind in the event of a retreat. Defeat would have resulted in the destruction of the army and with it the defeat of Russia. On July 10th, the advance guard of the 4th French Cavalry Corps Latour-Maubourg, under the Polish General Rosnietzky, was ambushed near Mir and was defeated by Cossacks under General Platow . On July 14th, the Russian army left Drissa. On the same day there was another battle between Cossacks and Polish cavalry under Rosnietzky near Romanowo.

After the rains of the first few days, a heat wave had set in, which affected both sides. Clausewitz reported that he had never suffered so much from thirst in his life. On the French side, the supply situation was still catastrophic, dust and heat made the soldiers more difficult. The army's losses increased, and in the first two weeks it had already lost 135,000 men without any major fighting. Thousands of horse carcasses lay along the marshland. Medical care did not work because the ambulance carts remained behind. There was a lack of vinegar, which was used for disinfection, as well as medicines and bandages. As Larrey reported, shirts, later paper, canvas, or hay were used to bandage the wounded. There was no substitute for the medication, nor for the vinegar.

Barclay de Tolly takes command

After the army arrived in Polotsk on July 18, the Tsar handed over command to Barclay de Tolly and traveled to Saint Petersburg via Moscow. In a manifesto on the same day, the tsar called on the Russian nobility to provide soldiers and stated that a commander-in-chief for the army should be appointed later. Barclay de Tolly left 25,000 men under General Wittgenstein in Polotsk to secure the way to Saint Petersburg, the 2nd and 6th Corps of Napoleon's army marched towards Polotsk. Barclay de Tolly moved with his army to Vitebsk , where he wanted to unite with the 2nd Western Army. Napoleon tried to prevent the unification of the two armies. On July 23, General Nikolaï Raïevski, commanded by Bagration with his corps to Mogilev , was able to hold up Marshal Davout's troops for only one day and had to withdraw. As a result, a march north to Vitebsk was no longer possible. Bagration had to move towards Smolensk . Barclay de Tolly had meanwhile reached Vitebsk and sent General Ostermann's corps to Ostrowno as security. After three days of fighting, Ostermann was defeated on July 27th. On the same day there was a Russian success: more than 2,100 Saxons under General Klengel surrendered to Tormassov's army units after the Battle of Kobrin .

In order to still unite the two armies, Barclay de Tolly also had to move towards Smolensk and left Vitebsk. Napoleon reached Vitebsk on July 28th and stopped the advance of his army. He announced that he would spend the winter here and that the war would continue the following year. Due to the catastrophic supply situation, this was difficult to do. The Russian supply stores had been destroyed, their own supply stores in Prussia and Poland were far away. The distance from the newly established depot in Vilnius to Vitebsk was more than 300 kilometers. Napoleon had overstretched his supply line. Given the poor road conditions, an adequate supply in winter and the subsequent snowmelt was not guaranteed. He had two alternatives: withdrawing the entire army to a realistic supply line or moving on to more fertile areas between Smolensk and Moscow.

Meanwhile, Davout and Bagration moved on parallel routes towards Smolensk. Wittgenstein defeated French troops near Kljastizy on July 31. During the subsequent pursuit, the Russian General Kulnev was fatally wounded the next day . Barclay de Tolly reached Smolensk on August 2nd, Bagration two days later. A few days later the fighting for Polotsk began between the corps of Wittgenstein and the two French corps.

With regard to Bagration, the tsar had not created a clear picture. Bagration was the senior general and was not expressly subordinated to Barclay de Tolly. Since he was also Minister of War, he took over command. Bagration did not agree with the warfare of Barclay de Tolly, he was particularly supported by General Jermolow , chief of the general staff of Barclay de Tolly. In several letters to Yermolov and General Araktschejew , Bagration had complained about Barclay de Tolly's retreat tactics for weeks. For many Russians, as a Livlander, he was a German. In fact, he preferred to speak German and only poorly Russian, which is why he liked to surround himself with German officers. When he summoned Clausewitz to the General Staff without consulting Yermolov, disputes broke out between Yermolow and Colonel Woliehen , who had mediated this. Before that, Barclay de Tolly had already employed Leopold von Lützow under similar circumstances . Also Eugen of Württemberg and the Russian Colonel Toll supported Bagration and wanted the took over the command. General Bennigsen himself had ambitions for the supreme command and also advocated a replacement of Barclay de Tolly. These intrigues and the fear of the Russian nobility for their possessions led to the appointment of Kutuzov as commander in chief.

On August 7th the two Russian armies advanced from Smolensk towards Rudnia. The following day there was a battle between the cavalry units of General Sebastiani and the Cossacks under Platow near Inkowo, Sebastiani withdrew. Sebastiani's documents fell into the hands of the Russian army. Wolzüge, who evaluated this, found a letter in which Marshal Murat Sebastiani had warned of an attack. According to Wolhaben, the text read as follows:

“I have just learned that the Russians want to carry out a forcible reconnaissance in the direction of Rudnia; be on your guard and withdraw except for the infantry who are dependent on you for support ... "

Barclay de Tolly also confirmed that the Russian plan had been betrayed. Among others, Woldemar von Löwenstern , on the staff of Barclay de Tolly, came under suspicion. He wrote in his "Memories of a Livonian" that he was sent to Moscow as a courier and unsuspectingly delivered a letter with the order to arrest him. Three other officers of Polish origin and Prince Lubomirsky had suffered the same fate. Lieutenant Colonel Graf de Lezair, a native of France and adjutant to Bagration, arrived shortly afterwards in Moscow and, unsuspectingly, brought his own arrest warrant. Löwenstern was released soon afterwards, Lezair not until 1815. As Wologene later wrote, Lubomirsky, an adjutant of the Tsar, was the culprit. In Smolensk he happened to overhear the conversation of some generals and in a letter he warned his mother, who was in her castle in Lyadui in the intended battle zone. Murat had his headquarters in this castle, which Lubomirsky did not know, of course. After the defeat of Inkowo, Napoleon set his troops on the move again and left Vitebsk. His army rallied in the Smolensk area, Barclay de Tolly and Bagration had to withdraw. The Russian rearguard under General Newerowski was involved in a battle with the 3rd Corps of the French Army near Krasnoi on August 15, in which they suffered considerable losses and lost nine cannons. It was Napoleon's 43rd birthday and that evening the captured cannons were presented to him.

The fortifications of Smolensk were in a poor condition and could not be maintained in the long term. Barclay de Tolly therefore only wanted to defend the city with part of his troops, while the army of Bagration was to retreat eastwards to Dorogobusch. The rest of the 1st Western Army should take over the flank security. The defense of the city was only intended to ensure the retreat of the two armies. On August 17th the battle for Smolensk broke out . Napoleon's main army had only 175,000 men before the battle. In total, he had already lost more than a third of his army, mainly to disease, exhaustion and desertion. The Russian army had also suffered losses through desertion on the way to Smolensk, mostly soldiers from the Polish territories occupied by Russia. In addition, there were casualties due to illnesses from which the Russian army was not spared. After two days of fighting, the Russian army withdrew from Smolensk, and Wittgenstein also had to withdraw in Polotsk. The commander of Bavaria, General Deroy , was fatally wounded in the fighting for Polotsk, as was General Justus Siebein . Marshal Oudinot was wounded, as were the Bavarian generals Karl von Vincenti and Clemens von Raglovich .

During the retreat, Barclay de Tolly succeeded on August 19 at Walutino in repelling French troops. General Junot's corps did not intervene in the fighting, thus preventing a possible French victory. The French General Gudin was fatally wounded and the Russian General Tuchkov was seriously wounded and taken prisoner.

Kutuzov becomes commander in chief

After the Battle of Smolensk, 67-year-old Kutuzov replaced Barclay de Tolly, who was later accused of destroying Smolensk. In fact, the city was caught on fire by artillery fire, and soldiers on both sides had started fires during the fighting to secure their retreat or prevent the enemy from advancing. Barclay de Tolly had given the order to burn the warehouses. Since the city consisted to a large extent of wooden houses, these fires had devastating consequences. On August 20, the tsar appointed Kutuzov commander in chief. The decision in favor of Kutuzov had already been made three days beforehand; a committee of six generals convened by the tsar had submitted this proposal. The Tsar had delayed Kutuzov's appointment because he didn't like him. A native of Russia and an experienced general, Kutuzov had the support of the Russian people and the nobility.

Barclay de Tolly and his troops had reached Zaryovo-Saimishche on August 29, where they began to build positions for a battle. On the same day, Kutuzov joined the army and ordered the expansion of the positions to be accelerated. On the afternoon of the next day he gave the order to withdraw. On August 31, the army reached Gschatsk (now Gagarin) and began building entrenchments again. This time General Bennigsen, meanwhile Chief of Staff of Kutuzov, did not like the position, and again Kutuzov ordered the retreat. In Barclay de Tolly's view, the two positions were not chosen for battle simply because he chose them. This would have diminished Kutuzov's success in the event of a victory. Regarding the further course of events, he wrote to the Tsar: "The two armies, like the children of Israel in the Arabian Desert, withdrew from place to place without rule or order, until fate finally led them to the position of Borodino."

The Russian Orthodox Church had meanwhile called for resistance against the "antichrist" Napoleon. He would desecrate the churches, kidnap women and children, and even the serfs would lead a worse life under Napoleon than under the Russian nobility, declared the priests. The Russian people were very religious, and the appeal did not fail to have its effect, the resistance of the civilian population increased. Some farmers had already fought against looting before, but it was about their own property and the protection of families, now it was also about faith and the fatherland. Accordingly, Kutuzov formulated his order of the day before the Battle of Borodino : “With trust in God we will either win or die. Napoleon is his enemy. He will profane his churches. Think of your wives and children who count on your protection. Think of your Emperor who is with you. Before the sun goes down tomorrow, you will have written on this field with the blood of the enemy the testimony of your faith and your love of the country. "

On September 7th, the battle of Borodino took place. The Grande Armée lost less than 30,000 men. The Russian army lost more than 50,000 soldiers. The battle was led on the Russian side by Bagration and Barclay de Tolly, both of whom intervened in the fighting at the head of their troops. Bagration was shot in the lower leg and died 17 days later. Kutuzov had his headquarters near Gorky, from where he could hardly follow the battle. When he found out about the defeat, he had a fit of rage and refused to believe it. He then proclaimed a Russian victory, and it is still widely said today that it was at least a draw. The facts speak against it. Kutuzov had to withdraw and reached Moscow with only about 70,000 operational soldiers from the previous 128,000. Napoleon reached Moscow with about 100,000 soldiers from fewer than 130,000 before. Compared to his original strength he had already lost more than two thirds of his main army by this time, plus the high loss of horses, which would later have dramatic effects. In the battle of Borodino a large part of Napoleon's remaining cavalry was destroyed. For lack of horses, cavalry units were formed on foot.

Wuerttemberg, Saxony, Bavaria and Westphalia suffered heavy losses in the battle. The Westphalian losses alone amounted to about 3,000 men, the Westphalian generals Tharreau, Damas and von Lepel were killed, the generals Hammerstein and von Borstel were wounded. The Württemberg generals von Breuning, von Scheeler and the Bavarian general Dommanget were wounded.

The occupation of Moscow

Since Kutuzov had announced a victory at Borodino, no reason was initially seen in Moscow to leave the city. The decision to evacuate the city was not made until the afternoon of September 13th. When Marshal Murat wanted to move into Moscow on September 14th, the city had not yet been completely cleared, many citizens of Moscow and soldiers of the Russian army were still in the city. After negotiations, Murat agreed to wait a few hours. In the afternoon he marched into Moscow. The Russian army had to leave nearly 10,000 wounded or sick soldiers behind. Several thousand Russian stragglers were captured, some of whom preferred to have participated in the sacking of Moscow and lost touch with the army in the process. Moscow merchants had asked them to plunder because they did not want their goods to fall into French hands. Heinrich von Brandt , an officer in the Vistula region, reported that entire wagon trains with flour, groats, meat and schnapps were found when they marched in. On the same day, the victory of Borodino was announced in Saint Petersburg. Victory was celebrated for days, and Kutuzov was appointed marshal and prince.

On the evening of September 14th, the first fires broke out in Moscow , possibly caused by drunken French soldiers through careless handling of fire. These fires were largely under control the next morning. The following night, new fires broke out in many places in Moscow. A storm on September 16 caused the fire to spread quickly. 75% of the city, two-thirds of which consisted of wooden houses, was destroyed. Many people died in the flames, including wounded or sick Russian soldiers. Looting by the French army had officially been banned, but in the face of the fire, anything that had any value and could be moved was taken from the houses. In a letter to the Tsar on September 20, Napoleon blamed the governor of Moscow, Count Rostoptschin , for the fires. According to his account, 400 arsonists were caught in the act. They named Rostopchin as their employer and were shot. The city's fire engines had been removed from the city or destroyed on Rostopchin's orders. After the fire, 11,959 deaths and 12,456 horse carcasses were counted. Of 9,158 houses, 6,532 were destroyed, of the 290 churches 127 affected.

John Quincy Adams wrote that the first rumors that Moscow was occupied began to circulate in Saint Petersburg on September 21. But he also mentioned that there were other rumors: the French army had been defeated and Napoleon was fatally wounded. Officials remained silent. It was only announced on September 27th that Moscow would have to be evacuated. According to Adams, presented as an event of unimportant importance, be it irrelevant to the outcome of the war.

The fire in Moscow is not really of decisive importance, since nevertheless significant quantities of material for supplying at least the infantry could still be found. The status of the French army increased during the stay due to the arrival of stragglers. Nevertheless, enormous lack of discipline in the form of uncontrolled looting and requisitions had a negative effect on the supply situation. Found stocks of spirits led to devastating excesses of the French soldiers. Napoleon himself resided in the Kremlin , which was unharmed. Most of the army, less comfortable, was housed outside the city. Napoleon waited in vain for the Tsar to offer him negotiations. Several times he sent negotiators to Kutuzov to offer negotiations. The tsar was unwilling to negotiate and on October 4th forbade Kutuzov to hold further talks. Alexander I was annoyed because he had already informed Kutuzov in August, before his departure for the army, that all talks and negotiations with the enemy that could lead to peace should be avoided. His letter was a clear rebuke to Kutuzov: “Now, after what has happened, I must repeat with the same determination that I want you to observe this principle, which I have adopted, in its greatest extension and in the strictest and most inflexible manner. “With the exception of a few outpost skirmishes, there was a kind of tacit ceasefire until this ban, as Napoleon initially waited for offers to negotiate and, when these failed to materialize, offered negotiations himself. The Russian army was able to take advantage of this and brought in reinforcements. Napoleon had twice sent General Lauriston to Kutuzov as a negotiator. When Lauriston returned on October 13 with no result, Napoleon decided to withdraw.

By now Britain had participated in the war with substantial funds and arms deliveries to Russia. The British General Sir Robert Wilson was the only soldier to take part in the campaign. Captain Dawson Damer later followed as his adjutant. In Saint Petersburg there were calls for peace, even from the mother of the tsar and his brother, the Grand Duke Constantine. Freiherr vom Stein , an adviser to the tsar, wrote that many in the area around the tsar wanted peace, including General Araktschejew. On the other hand, there were many nobles who would not have supported a peace agreement.

Napoleon's retreat

At the beginning of October Barclay de Tolly left the army after further intrigues against him; Tormasov took command of the 1st Western Army. On October 17, Wittgenstein, who had received reinforcements from Finland, attacked the French troops at Kljastizy and a day later Polotsk. The Russian plan provided that Wittgenstein should repulse the French in the north, in order to later unite with the Russian southern army under Chichagov. This would block the route of retreat for Napoleon's main army. The 2nd and 6th Corps of the Grande Armée had to withdraw from Polotsk. On October 18, Murat was defeated by Russian troops in the Battle of Tarutino , and Napoleon left Moscow a day later. Despite the lack of horses, a large number of carts were used to transport the booty from Moscow. High officers in particular had obtained paintings, wine, furs and other valuable objects from the palaces in Moscow (Napoleon had the cross removed from Ivan the Great's bell tower to take with him to Paris). Many wounded and sick, however, had to walk, and a large number were simply left behind in Moscow. Many residents, including the French, followed the army because they feared reprisals if the Russians returned. Moscow was a European metropolis where many foreigners lived and where there was a French theater.

A French officer described the withdrawal: “Behind a miserable artillery and an even more miserable cavalry, a disordered, bizarre crowd passed, reminiscent of long-forgotten images - the terrible hordes of Mongols who had carried their belongings and loot . A great train of carriages and wagons was moving; there were long columns laden with so-called trophies; Bearded Russian men marched on, breathing heavily under the weight of the looted goods they had gathered; there other prisoners drove whole herds of emaciated cows and sheep together with the soldiers; Thousands of women, injured soldiers, officers ' boys, servants and all kinds of rabble drove on the wagons loaded with all sorts of treasures . "

As the rearguard, the Young Guard under Marshal Mortier stayed in town until October 23. Cossacks invaded the city, the Russian general Wintzingerode was taken prisoner. Since he was born in Hesse, he was a member of a federal state of the Rhine Confederation for Napoleon and thus a traitor, which is why he demanded his execution. Weeks later Wintzingerode was freed from Cossacks. When the Young Guard withdrew, parts of the Kremlin were set on fire or blown up. Large quantities of weapons, ammunition and powder had been found there. Heavy rain prevented a major catastrophe and the Kremlin was largely preserved.

When Moscow was reoccupied by the Russians, there were massacres of stragglers, wounded or sick French soldiers by Cossacks, residents of Moscow and armed peasants. In their eyes, the French were responsible for the fire and they were also the devil's helpers (the Russian Church had declared Napoleon an antichrist and thus the devil). Collaborators or people believed to be involved were also killed. Vengeance also played a role, as French soldiers had previously committed rioting and atrocities.

After leaving Moscow, the French army moved south-west. The Russian general Dochturov defended Malojaroslawez against the corps of Eugène de Beauharnais on October 24, but had to withdraw in the afternoon. During the day the town changed hands several times. Kutuzov avoided a decisive battle and ordered the retreat towards Kaluga. Napoleon did not want to pursue Kutuzov and withdrew on October 26th. He marched back on the looted route to Smolensk, on which there was neither enough food for humans nor for horses.

General Bennigsen, too, had since left the army after there were intrigues against him and differences with Kutuzov. This got rid of an annoying competitor. Bennigsen was not entirely innocent; in letters to the Tsar he had belittled Kutuzov. Among other things, he tried to blacken him by saying that a woman disguised as a man would serve on the staff of Kutuzov. This was probably Nadezhda Andrejewna Durowa , who confirmed in her autobiography that she was briefly on the staff of Kutuzov. The tsar was aware of their presence in the army, and so Bennigsen had put himself on the sidelines.

The hesitant and timid Kutuzov was not an equal opponent for Napoleon. On November 3, the battle of Vyazma broke out . Russian troops under General Miloradowitsch initially faced a superior force of the French. In the course of the morning the division of Eugen von Württemberg joined them. Kutuzov, with most of the army only a few kilometers from the battlefield that morning, did not intervene. His troops camped near Binkowo. Only in the afternoon did he send 3,000 cavalry troops to support. They reached the battlefield just before dark.

Napoleon reached Smolensk on November 9th, was able to gather his troops there, and did not leave the city until five days later. For the return march Napoleon had planned the route via Minsk. It was shorter and a million daily rations were stored in the French-occupied city for its soldiers. Even in Krasnoi, Kutuzov was unable to stop Napoleon despite his strong superiority. Later he allowed the two French corps from Polotsk to unite with Napoleon's main army, which made the transition across the Berezina possible.

Crossing over the Berezina

With three Russian armies, Kutuzov was unable to prevent the passage of 28,000 soldiers from the Grande Armée across the Beresina, although Russian troops were on both banks. The armies of Tschitschagow and Wittgenstein, some of which operated separately, were not strong enough with around 30,000 men each against only 50,000 poorly supplied soldiers of the Grande Armée. Chichagov, who had previously taken Minsk and thus nullified Napoleon's plan, allowed himself to be distracted by a faked transition elsewhere. Wittgenstein was able to capture the stragglers on the east bank of the Beresina and was characterized by the fact that a French division under General Partouneaux had to surrender to his troops. She had lost touch with her army. Kutuzov himself was far behind with more than 50,000 men and did not take part in the battle of the Berezina . A political solution was thus missed after a capitulation or capture of Napoleon. Chichagov has been retired for his alleged failure. With Kutuzov the tsar limited himself to reproaches because Napoleon was able to escape.

The end of the campaign

In France there was a coup attempt under General Malet at the end of October . Malet had announced that Napoleon was dead. Napoleon left the army on December 5, 1812, although he had heard of the coup attempt in Smolensk at the beginning of November, and traveled to Paris. An earlier departure was too risky as he was still in Russian-controlled territory. He handed the command over to Murat. More important than the attempted coup by Malet was the fact that Napoleon had to build a new army.

Vilna

The Napoleonic troops suffered particularly great losses on their retreat to Vilnius , where from December 7th to 9th, 1812 soldiers were frozen to death in the open, unsupervised at temperatures as low as −39 degrees Celsius and the stragglers were killed by pursuing Cossacks. The French army left Vilna on December 10th, leaving behind the sick, wounded and exhausted. When the Cossacks entered there was a massacre in which the civilian population participated. “About 20,000 wounded, sick and ailing remained in Vilnius. With them, enormous supplies fell into the hands of the enemy. "

The Württemberg lieutenant Karl Kurz wrote about the fate of the soldiers who remained in Vilnius: “Halls and rooms ... were full of dead and dying people who gnawed their dead comrades in their famine. ... The misery of the poor prisoners was indescribable in the days of December 11th to 15th, in which more than 1,000 officers and 12,000 commons of all nations perished through the weapons of the enemy, through abuse of all kinds, through cold and hunger The massacre only ended when the regular Russian army arrived - the Cossacks were not part of the regular army.

Those who remained in Vilnius after the troops had withdrawn on December 10th were apparently sheltered by parts of the population, then robbed, tortured and cast out. The living lay next to the dead in the hospitals. In the first 6 to 8 days, the hospitals were not supplied. Then the dead were thrown out of the windows or dragged down the stairs by their legs. In April 1813 the surviving officers and soldiers were "taken into the interior of Russia".

On December 21st, the Tsar arrived in Vilnius and took command of the army again. “The old guy should be satisfied. The cold weather has done him a great service, ”he said of Kutuzov. It is questionable whether Napoleon would have given himself prisoner. Larrey had supplied him with a poison capsule which he took in April 1814 after his abdication. The poison had lost its lethal effect and only caused severe stomach pain.

Dissolution phenomena

On December 14th, remnants of the Grande Armée crossed the frozen Nyemen and reached Poland. Murat wrote to Napoleon: "I will report 4,300 French and 850 auxiliaries to the emperor as soldiers ready for action". A handful of stragglers followed later. The 10th Corps, in which the Prussian auxiliary corps was, was still in Russia and was marching towards Prussia. The Grandjean division of the corps reached Prussia with 6,000 men, mostly Poland, Bavaria and Westphalia. The Prussian corps still had 15,000 soldiers from 20,000 previously. The Tauroggen Convention on December 30th made it neutral and no longer intervened in the fighting. The Austrian corps stopped fighting on January 5th. It originally consisted of 33,000 men and at the end of the campaign numbered 20,000 men, plus remnants of the 7th Corps. 100,000 soldiers of Napoleon's army were taken prisoner, many of them died of their wounds, illnesses or frozen to death on the march into captivity, whoever remained was mostly killed. The Russian soldiers who were taken prisoner by the French suffered the same fate. The surviving prisoners were released from Russia until 1814. As soon as their homeland joined the fight against Napoleon, they were released. According to Holzhausen, 2,000 to 3,000 of the German prisoners returned. Some stayed in Russia, like the Württemberg regimental doctor Heinrich von Roos. He was captured on the Berezina and later practiced in Saint Petersburg.

The lists of Lieutenant Heinrich Meyer from Hanover include the names of other soldiers who remained in Russia. Meyer was sent to Russia by the Prussian government to clarify the fate of missing soldiers. It was primarily about soldiers from the areas that fell to Prussia after the war. The reason was legal. It was about inheritances, remarriage requests from wives of missing soldiers and the like. In cooperation with Russian authorities, Meyer was able to determine the fate of around 6,000 soldiers, most of whom had died. Quite a few had joined the Russian army. This obviously does not mean the Russian-German Legion, as Meyer differentiates between them in his notes. German soldiers who joined the Russian army were entitled to a piece of land in Russia after the war.

The Grande Armée was accompanied by tens of thousands of civilians, including craftsmen, administrators and clerks. Those who could afford it had servants or cooks with them. It was not uncommon for wives and children to accompany the army. Soldiers of fortune and criminals also followed her to enrich themselves from war. Most of these also perished. In the spring of 1813, more than 240,000 dead were burned or buried in mass graves along the retreat route of the Grande Armée, including the dead of Borodino, who were abandoned after the battle. 130,000 horse carcasses were burned or buried.

Balance sheet

"General Winter"

Often the winter is blamed for the defeat of Napoleon, but the Russian soldiers fought under the same weather conditions, although they were more familiar with winter hardiness than the French. The snowfall started on November 6th. An analysis of the French officer losses mentioned by Martinien for this month shows that almost 90% of the time and geography involved fighting. For a few days it got a little warmer, which is why the Beresina was not frozen over.

Winter only reached its lowest temperatures after the transition. Before that, Napoleon's army was repeatedly involved in fighting. She had too few horses and had to burn many of her wagons, cannons were made unusable and left behind. Even the pontoons carried to build bridges were burned a few days before the army reached the Berezina.

In fact, Napoleon was just as unprepared for a winter war as the German Wehrmacht in Moscow 129 years later. There was a lack of warm clothing and the horses were misted for these temperatures. This often led to accidents with the carts. Only the Polish and Prussian cavalry had their horses sharply shod and were thus prepared for the winter conditions.

In the case of the Arrière Guard (rearguard), when they withdrew to Vilnius, heavy losses were incurred as a result of the fighting in retreat, the loss of food and, on December 6, 1812, due to the extreme cold of "a few 20 degrees". The cold had risen to "the highest" on December 7th. Many people died in the bivouac in Oszmiana during the night of December 6th to 7th . The remnants of the troops were hardly usable as arrière guards and arrived at the gates of Vilna on the evening of December 8th.

The hygienic conditions were a big problem. Most of the soldiers had lice that transmitted diseases such as typhus or Volhynian fever . If someone collapsed exhausted, their clothes were taken over and with them the lice. Epidemics broke out in Russia as early as the summer and were spread across the country by the marching troops and the fleeing population. The armies later dragged these diseases to Poland and Germany. Thousands of soldiers and hundreds of thousands of civilians on both sides died of disease. A census in Russia in 1816 showed a population decrease of one million people.

Prisoners

Few prisoners survived on either side. Russian soldiers who were captured by France were barely given anything to eat, especially when they were retreating, as the guards themselves did not have enough to live on. Every now and then the prisoners received parts of horse carcasses. Anyone who was so physically weak that they stayed behind on the way was killed. With the exception of the officers, wounded Russians were mostly not cared for, because one was hopelessly overwhelmed with caring for one's own wounded. They were looted - filled haversacks, alcohol, money and valuables - and simply left behind. In most cases that was her death sentence. After Baumbach, Russian wounded men were found living eleven days after the Battle of Borodino, who were suffering from great hunger and hardship.

French soldiers who were taken prisoner by Russia did not have it much better. Many were looted by Cossacks, often including their clothes, shoes or boots, and had to march barefoot and almost naked in the freezing cold. Few survived; whoever stayed lying was killed. The tsar was forced to offer a reward for every prisoner who was handed over alive. The Cossacks were mostly used for reconnaissance and for surprising raids. Contrary to the circumstances, the regular Russian army mostly treated the prisoners properly. Löwenstern told of French stragglers who saw the fire of his soldiers and joined them. Russians and French sat together by the fire and the next morning the Russian soldiers moved on. They only hindered prisoners. However, Löwenstern also reported a massacre by the civilian population. When he and his soldiers came to a town and the residents recognized their Russian uniforms, they attacked unarmed French stragglers. There are a number of reports of torture and murder of French prisoners by Russian civilians.

Most of the Grande Armée soldiers captured in Russia died of disease. Ordinary soldiers, often malnourished, sometimes wounded and without adequate medical care, had little chance of survival in the event of illness. The Bavarian Sergeant Josef Schraefel survived the captivity, although he fell ill. He reported that the dead were piled in the forest during the winter. His wife Walburga, who had accompanied the army as a sutler and stayed with him after his capture, died in Russia.

losses

The size of the losses cannot be clearly determined as there are many conflicting numbers. For western historians, the war ended in mid-December with the crossing of the Nyemen. In Russia, the Patriotic War has a different timeframe and was only ended later. As a result, troop strengths, casualties, prisoners and survivors differ from each other. Troops that did not intervene in the fighting until 1813 and have never been to Russia itself are included. On the other hand, as returnees, often only those units were considered that were actually armed and capable of fighting. Immediately after the war, the Prussian military scientist Clausewitz wrote that of the 610,000 soldiers in the Grande Armée, only 23,000 reached the western bank of the Vistula. According to the Soviet historian Yevgeny Viktorovich Tarle , about 30,000 men returned via the Nyemen. Heinz Helmert and Hansjürgen Usczeck, East German historians from the GDR military publisher , later assumed a total of 81,000 returnees and displaced people who dragged themselves back across the border by December 1812.

Many documents were lost during the war or later, which is why the extent of the losses will only be shown using a few examples. Of the 9,000 Swiss, 300 men came to roll call after crossing the Beresina, a large number of them wounded. This was followed by the lowest temperatures of the winter of 1812. Only some of these soldiers survived. Meyers Konversationslexikon , on the other hand, put the losses of the 16,000-strong Swiss auxiliary corps at 6,000 at the end of the 19th century. Henry Vallotton wrote that only 300 out of 12,000 Swiss survived the campaign. However, later research has shown that fewer soldiers from Switzerland were in Russia. In today's literature, the strength of the auxiliary corps is sometimes given as only 7,000 men.

Of 30,000 men of the Bavarian VI. Corps on December 13th, 68 combat-ready soldiers entered. Of more than 27,000 Westphalians, only 800 returned. Of the 15,800 Württemberg people, 387 men remained after the withdrawal. The Baden division , initially about 7,000 men, still consisted of 40 combat-ready and 100 sick soldiers on December 30th. The Saxon cavalry brigade Thielmann was almost completely destroyed near Borodino, 55 men returned. 59 of 2,000 Mecklenburgers returned. Only the two auxiliary corps from Austria and Prussia, which never penetrated far into Russian territory and therefore had shorter supply and withdrawal routes, show lower casualties.

After the withdrawal, the Bavarians received reinforcements of 4,200 men by December 29. These troops did not leave Bavaria until October and are an example of the different ways in which the numbers can be interpreted in relation to the Patriotic War.

On June 26, 1813, the Austrian Chancellor Metternich had a meeting with Napoleon, which he recorded. Among other things, he wrote: “Napoleon collected himself, and in a calm tone he said the following words to me [...]: The French cannot complain about me; to spare them I sacrificed the Poles and the Germans. I lost 300,000 men in the Moscow campaign; there were not even 30,000 French among them. You are forgetting, Sire, I exclaimed, that you are speaking to a German. "

According to the Russian War Ministry, the number of prisoners in the western Russian governorates was 11,754 men on February 28, 1813, including 4,508 French, 1,845 Poles, 1,834 Spaniards, 1,805 Germans, 659 Italians, 617 Austrians and 218 Swiss. Tarlé, on the other hand, assumed up to 100,000 French who were in Russian captivity at the end of 1812. In addition, there are soldiers who had joined the Russian-German Legion, which, according to Clausewitz, was around 4,000 men in December 1812 and 5,000 men in the following May. As chief of the Legion's Quartermaster General, he was informed of their strengths. The Legion's first strength report from December 10, 1812, on the other hand, records only 1,667 men and two horses. The deviations between the strength report and Clausewitz's figures can be explained by the high level of illness caused by epidemics. According to Helmert / Usczeck, the legion of officers and men at the beginning of 1813 was 8,800 men. Freiherr vom Stein had put the strength at 8,773 men, although it is unclear where he got this number from, since the Legion only reached a strength of over 8,500 men in November 1814. It was not only made up of Germans: it is said that Dutch people volunteered in droves and Italians pretended to be Germans in order to be accepted. Unlike often in captivity, service in the Legion meant regular supplies, clothing and reasonable accommodation. Compared to the contingent that Spain provided, the number of prisoners is very high. Most of them belonged to Durutte's division, which was not deployed until November. They were mainly prisoners of war who were used more or less voluntarily. Many soldiers deserted.

There are few sources on the Russian losses; they amounted to about 210,000 men. General Wilson reported that Kutuzov's army had lost half of its soldiers in the four weeks before reaching Vilna. Out of 10,000 recruits sent to Vilna as reinforcements, only 1,500 soldiers reached the city, many of them sick.

aftermath

After the defeat of the Grande Armée in Russia, the Wars of Liberation began , which put an end to Napoleon's rule over Europe. At the beginning of 1813 Prussia became the first German country to terminate its alliance with France and allied itself with Russia and Sweden. In the summer Austria joined this alliance; and so Napoleon's army was inflicted the decisive defeat in the Battle of Leipzig from October 16 to 19, 1813 . After that, Napoleon's last German allies also switched sides. After the Allied invasion of France in March 1814, he was forced to abdicate and go into exile on the island of Elba. After his return and the reign of 100 days , he was finally defeated at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

In the meantime, the winners of the Congress of Vienna had already started to reorganize Europe, which Russia, Austria and Prussia intended to guarantee by founding the Holy Alliance . In France, which received the borders of 1792, returned with Louis XVIII. the Bourbons returned to the throne. Russia and Prussia shared the Polish Duchy of Warsaw. Prussia also received areas in western Germany, which it later combined to form the Rhine province . Lithuania and other formerly Polish areas remained Russian, as did Finland. Sweden was compensated for its loss with the annexation of Norway. In Congress Poland , under Russian rule, a liberal constitution was first introduced. The Polish-Russian antagonism worsened, however, leading to an uprising in 1830, which Russia put down. The constitution was repealed and Poland declared a Russian province.

Cultural legacies

In the period that followed, numerous literary works dedicated to the Patriotic War emerged, including Leo Tolstoy's novel War and Peace . In 1880 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky composed his famous overture solennelle “1812” op. 49 .

In the Russian language, the war left the word Sharomyga ( Шаромыга ), which means something like beggar, tramp , parasite. This was due to the numerous French deserters left by the war. They roamed the country and addressed the farmers as “cher ami” to ask them for something to eat.

The locations of the battles were taken into account when German emigrants settled in Bessarabia from 1814 onwards . The welfare committee, as the Russian settlement authority, gave these names to Bessarabian German settlements such as Arzys , Beresina , Borodino , Leipzig , Malojaroslawez, Paris , Krasna (Krasny) and Tarutino .

In the German areas on the left bank of the Rhine , ceded to France after the peace agreement of Campo Formio (1797), many soldiers were recruited for the Napoleonic army. The Napoleonic veteran cult was correspondingly large there later.

Memorial stones to the fallen / deceased soldiers

Especially in the area of today's Rheinhessen-Palatinate, to which the French Département du Mont-Tonnerre previously corresponded, veteran societies of the former Napoleonic army were founded in numerous places and group and individual monuments were erected. Such Napoleon stones also exist in Koblenz , Mainz-Gonsenheim (1839), Kreuznach (1843), Oppenheim , Ober-Olm (1842), Ingelheim - Großwinternheim (1844), Eimsheim (1852), Worms , Pfeddersheim , Grünstadt , Frankenthal (Palatinate) , Kaiserslautern , Zweibrücken and Biedesheim (1855).

The obelisk on Karolinenplatz in Munich was erected in 1833 by the Bavarian King Ludwig I to commemorate the Bavarians who fell in the Russian campaign.

See also

- Badener in the Russian campaign in 1812