Thidreks saga

The Thidrek saga is an extensive compilation of legends from the 13th century in Old Norse ; In addition to the older Norwegian version (and related Icelandic versions) there is also a more concise old Swedish from the 15th century ( Didrikskrønike ), which is mostly assumed to be a shortened and contradictory translation of the Norwegian manuscript that has survived . The saga tells in prose (for the works in verse form see Dietrichsepik ) the life of the hero Þiðrekr af Bern , who was known in the German-speaking area as Dietrich von Bern .

According to the majority of research, the figure of Thidrek (Didrik, Dietrich) of Bern is based on the person of the historical Ostrogoth king Theodoric . However, a considerable part of the older German philology has contradicted this assumption and instead considers an original Rhenish-Franconian saga about the Merovingian king Theuderich I , who in the heroic epic context with his son Theudebert I is also advocated as the legendary protagonist of the Wolfdietrich , as more likely. The essential literary changes from the historical Ostrogothic and / or Rhenish Franconian rulers to the legendary figure of Thidrek had already been achieved at the time of Charlemagne , who had an alleged Theodoric statue transferred from Ravenna to Aachen . Already in the Hildebrandslied (recorded around 830-840; probably older) Dietrich had to flee to a "Hun" ruler; but before Odoacer , who was actually his contemporary; not, as in more recent forms of saga, before Ermanarich , who actually lived about 150 years before Theodoric. Around this Thidrek are grouped a larger number of heroic sagas that originally belonged to other contexts , such as those of Siegfried , the Nibelung saga, the saga of Wieland the blacksmith and the Wilzen saga , the protagonists of which are linked to Thidrek through following or relatives. This makes the Thidrek saga the earliest compilation of German heroic sagas in prose form, which is why it is often used in German research.

Heinz Ritter-Schaumburg , who translated the old Swedish version of the Thidreks into German for the first time, put forward the controversial but so far unfounded thesis that the Thidreks relates to historical events during the migration period in Lower Germany and Dietrich von Bern does not identical to the Ostrogoth king Theodoric. Rather, Dietrich is a king of Bonn who has apparently not been attested in any other way . Knight's origin, however, connects Ritter with the family of the Frankish king Clovis I (father of Theuderich I), who, strikingly similar to Erminrik in the Thidrek saga, had ensured the systematic removal of close male relatives or possible heirs to the throne. However, Ritter-Schaumburg's interpretation of the Thidrek saga is rejected by large parts of the research.

The saga writer states that his story was “compiled from the story of German men, partly based on their songs, with which one should entertain great gentlemen”. Presentation of the saga would thus be sources from the Low German space (Sachsen) , partly in prose, partly in verse. At the end of the Niflung part, sources from Bremen, Münster and Soest are also mentioned. Since the High Middle Ages, with the penetration of a Low German aristocratic and merchant culture into the north (cf. Hanse ), Scandinavian interest in Dietrich increased, initially in Denmark, Sweden and Norway.

Sources

The Thidrek saga has come down to us in three parchment manuscripts in Old-West Norse (Old Icelandic-Old Norwegian) and an Old Swedish version in two very similar manuscripts. However, only copies of two of the old-west Norse parchment manuscripts are still available today.

The old Norse parchment manuscripts

Two of the three parchment manuscripts have been lost. They were probably destroyed in the Copenhagen city fire in 1728.

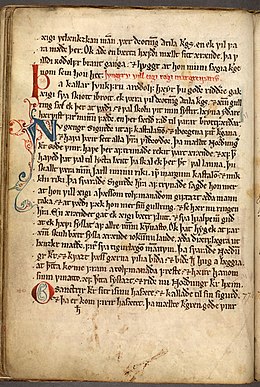

The third of the parchment manuscripts is therefore the oldest and is kept in the Royal Library in Stockholm. It is usually called "Membrane" (Mb) and was probably recorded around the middle of the 13th century in the Norwegian port city of Bergen . This version is preferred for translation into German. However, the text is no longer complete, especially at the beginning and at the end there are lacunae . This manuscript now contains only 129 and two blank sheets of originally 162 sheets, which were in 19 layers with 8 sheets each. 10 sheets were subsequently added to the eighth layer.

In the 1308-1314 manuscript index of the Bergen bishop Árni Sigurðarson a manuscript of the Thidrek saga is noted. This membrane, which is now kept in Stockholm, is suspected to be behind this. The chronological location of this manuscript in the Hanseatic and royal city of Bergen under Håkon IV is also important , as it allows conclusions to be drawn about the origins of the Thidrek saga.

The Stockholm membrane reveals the hand of five different writers or editors (Mb1 to Mb5). Mb1 and Mb2 were Norwegians, Mb4 and Mb5 were Icelandic; from these nationalities the origin of Mb3 is disputed. Mb2 subsequently wrote titles for Mb1 and Mb3 for Mb4 and Mb5. The scribes Mb2 and Mb3 were "main scribe" and "transcription manager", respectively. According to Carl Richard Unger's structure of the Stockholm and Old Icelandic manuscripts, the first edition comprises chapters Mb 1 to Mb 196. The third editor edited his predecessor by inserting 10 sheets about the story of Sigurd's youth (Mb 152–169, cf. Bertelsen I, 282-350). In addition, Mb3 deleted the following two sections of Mb2 (Mb 170–171, B. I, 351–352) and inserted his version about the Niflung family as an alternative (B. I, 322–325), so that two editors were retained. Comparable procedures can also be seen in the Wilzen reports (Part I: Mb 21–56); see. also the tales of death about Osantrix in Part II (Mb 134–145, here Mb 144) with the version in III (Mb 291-315, here Mb 292).

These editors can be recognized by the fact that they apparently used different templates. However, the same editor or writer occasionally used different templates with differing content. This makes the Thidrek saga particularly valuable for the genesis of the saga, which allows conclusions to be drawn about different versions of the traditions that have come to Old Norway. The best-known narrative contradictions within the Thidrek saga are two different death reports about the Wilzen king Osantrix and the origin of the Niflungs - these by the same writer (Mb3) twice in immediate succession with sometimes different names (Mb3 provides King Aldrian as Niflungsvater) and the number of siblings (Mb2 also mentions Guthorm or Guttorm among the Niflung Brothers fathered by King Irung ). Narrative duplications, insofar as these concern the sequence of chapters and are less significant in the overall context, are encountered, for example, in the announcement of Hildebrand's sword guidance (belatedly according to Mb 187) and the acquisition of Thidrek's horse Falke according to Mb 188, which, however, according to Mb 100 has long been in the possession of Hero is. Presumably, these cases are not due to erroneous displacements, but to deliberate depositing of different source versions.

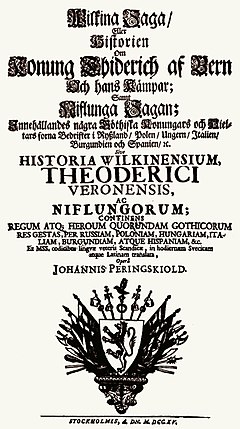

The membrane (Mb) was mostly preferred for translations into German, mainly because it is the oldest text in the Thidreks saga. The copies A + E and B + D contain some deviations. Johan Peringskiöld, at that time working as a secretary, antiquarian and Icelandic translator in Sweden's National Archives antikvitetsarkiv , has in his handwriting edition of 1715, although the Anfangslakune of Mb with the accounts of Samson's conquests, Thidreks and Hildebrand's gender, Heimirs introduction and Hilde-Grim -narrative well filled with an old Icelandic manuscript, but not published Thidrek's dragon fight, Heimir's monastery episode and the stories about his and Thidrek's end as a substitute for the final mood. However, these reports are contained in an older Swedish manuscript (see below).

The old Icelandic manuscripts

Two good Icelandic paper manuscripts from the 17th century exist in the Arnamagnaean collection of both lost ancient Norwegian text documents, which are labeled A (AM 178, fol. = Sigle A) with E and B (AM 177, fol. = Sigle B) with D are designated. The manuscripts comprise 109 (A) and 194 sheets (B) and were in the possession of the Icelandic scholar Árni Magnússon , who noted for manuscript A that these traditions come from Austfjarða (East Fjords) and the town of Bræðratunga with an attached prologue .

In the manuscript edition by Henrik Bertelsen, these two manuscripts are used to fill in the lacunae in the older old Norwegian membrane and to represent text deviations. Manuscript A is particularly noticeable because it agrees in many ways with other Nordic traditions such as the Vǫlsunga saga . This is what Kriemhild calls this manuscript under the name Gudrun, she describes Brynhilðr as Buðli's daughter and is the only one to tell of her early death after Sigurðr or Siegfried's death. She also knows the name of Siegfried's sister Signy .

The old Swedish version

In addition to the measure based on a common source base altwestnordischen traditions of Thidrekssaga there's is Old version in two manuscripts (Sv A and Sv B) from the 15th century, the Didrikskrønike , Didrik-Krönikan (Dietrich Chronicle) or Sagan om Didrik af Bern is called . The older version Sv A comprises 159 sheets and is dated around 1500 under the signature E 9013, previously under Skoklosteramlingen no 115./116. It initially provides (sheets 1 r –36 r ) the chivalric novel Hertig Fredrik af Normandie from the Eufemiavisorna cycle . The tradition of the Þiðriks saga af Bern (sheets 37 r - 159 r ) was written by two scriptors. The somewhat more recent, fragmentary manuscript Sv B with the codex designation K 45, 4 °, dates back to the first decade of the 16th century, with particularly conspicuous Danisms only passed down to Chap. 229, in which the narrative sections about Sigurd's youth and his wedding to Crimilla are missing.

Overall, these manuscripts report more factually and briefly. In terms of content, Sv A differs from the Icelandic traditions, especially in the final part, in that it constructs a second death story about its title hero, which is nowhere else handed down: In the end, Didrik fights with Wideke Welandsson , who killed Attila's sons and Didrik's brother, defeated him; but he dies of his wounds after sinking his sword Mimungs ( Mymmings ) in a body of water in Svava .

The literary scholar and journalist Heinz Ritter-Schaumburg translated these manuscripts into German for the first time and named them "Svava". That the Swedish version of the Thidreks saga is a translation, she herself indicates at the very end, with the words:

- Herr Didrik's book has now come to an end, God may send His grace to him who did it in Swedish.

This is the main reason why the Old Swedish version is generally considered to be a shortened translation of the Old West Norse manuscripts. The fact that the Swedish tradition contains no blatant contradictions or duplications, such as Mb, can be traced back to the fact that the scriptors consciously tried to produce a uniform and non-contradictory work.

Ritter-Schaumburg denies this dependency and considers the Swedish version to be the translation of a Danish or originally Low German text that no longer exists, which is also supported by the Low German names of the heroes and numerous Danisms. He also refers to the relationship between the two manuscripts Sv A and Sv B in the Swedish version, which he believes must be separate translations of the same text. This could be recognized by the frequently used synonymous but different words. However, due to the close relationship between the two manuscripts, the foreign source must have been the same and could therefore not be the membrane.

The deviations between Sv A and Sv B, however, are within the limits of what late medieval scribes can trust. It is therefore unnecessary to assume that the translation is done twice. Where the Swedish version uses names that look more similar to German legends than the corresponding names in the Old West Norse manuscripts, these are German legends that were very popular in the late Middle Ages; the translator obviously knew various legends in the form that was current in Germany at the time, in addition to the original.

The text criticism of the Swedish manuscripts complains about a few incorrect translations and misinterpretations, which Kay Busch sums up as follows:

- The pivotal point here is the localization of Vilkinaland, which was probably originally located in Slavic territory, but in the old Swedish translation it was regarded as the old name for Sweden. The content of the saga was of great political importance as early as the 15th century, which can be clearly seen in the fact that text passages from this translation found their way into the prose cronica of King Karl Knutson. It is very likely that this early transmission was also initiated by the ruling party.

content

Overview of the content of the chapters

In the following, the table of contents of the Membrane tradition, supplemented by the old Icelandic manuscripts A and B by Carl R. Unger (Mb), followed by volume and page references from Henrik Bertelsen's manuscript edition. The subdivision into the narrative sequences comes from Susanne Kramarz-Bein (2002).

I. Narrative sequence: youth and experimentation

Only the Old Icelandic manuscripts A and B and the old Swedish version are text witnesses. The beginning of Mb is lost.

- Prologue of the Thidrek Saga (ThS). Contains a legendary assessment from old Norse literature about the sources and the scope of the saga. The date of origin of this prologue corresponds to the dating range of the two Old Icelandic AB manuscripts.

- Mb 1–14 (I, 8–32) "Knight Samson and his sons": Knight Samson, an almost gigantic, black-haired warrior, falls in love with Hildisvid, the daughter of Jarl Rodgeir of Salerni (mostly equated with Salerno , is related to this of the localities, however, rather around a Sal-Franconian seat in today's Belgium), and kidnaps them with their consent. At first he lives with her as a robber in a forest; there he kills the Jarl and King Brunstein, who want to bring Hildisvid back. Finally he is elected duke on a thing by the citizens of Salernis and then even made king. With Hildisvid he has two sons, Erminrik and Thetmar. In old age he started a war against Jarl Elsung von Bern (compared to Bonn, where Verona in the Rhine region was usually equated with Verona in northern Italy). He killed Elsung with his own hands and married his daughter Odilia to his younger son Thetmar, whom he made King of Bern. With his older son, Erminrik , he moves further south towards " Rome ", but dies on the way there. Erminrik conquered the majority of the Roman territory " including many islands of the Greek sea ". (The old Swedish version, which also allows a more northerly reporting geography, only mentions “ Grekin ”, which can be interpreted as the Graacher area east of “ Roma secunda ” or Trier .) Samson made his third son, Aki, whom he had with a concubine Duke of Fritila.

- Mb 15–20 (I, 32–43) “Jung Thidrek”: Narrated by Hildebrand, King Thetmar and his son Thidrek . Thidrek grows up to be a man of enormous strength and with many of the good qualities of his grandfather Samson. Hildibrand (corresponds to the German Hildebrand ), son of the Duke of Venedi (often equated with Venice ), comes to Bern and is appointed by Thetmar to educate young Thidrek. On the hunt, Thidrek catches the dwarf Alfrik (the northernized form of the German name Alberich ), who, in order to be released, delivers the sword, Nagelring, forged by himself . With this great sword Thidrek fights with Hildebrand's help against the magical giantess Hild and her husband Grim. Although the halves of the body of the slain Hild can join together again by magic, he succeeds in killing her for good. Thidrek's most valuable loot is the helmet of the two monsters called Hildigrim. These and other feats made Thidrek famous.

- Heimir is the son of Studas, the manager of Brynhild's stud at Seegard Castle in Swabia. The best of all hero horses come from the Brynhild stud. Heimir was originally called Studas after his father; however, since it is as fierce as the dragon Heimir, the most vicious of all dragons, it is later named after him. Heimir gets the stallion Rispe from his father Studas. Heimir moves to Thidrek and challenges him to a duel; the victors should own the weapons of the loser. Thidrek wins; Heimir lets himself be accepted by him as a companion.

This is where the preserved part of Mb begins.

- Mb 21–56 (I, 44–63 & II, 61–105) “First editorship of the Wilzensaga”: The Wilzen are a people that the ThS locates contradictingly: mostly south of the Baltic Sea, sometimes closer to Russia, sometimes more to the west ; but sometimes also as "Greater Sweden" with parts north and south of the Baltic Sea. This saga is recorded in Mb in two versions ("editorial offices"), which do not show any major differences in content, but differ stylistically. It looks like two translators translated the same German text, or, more likely, an original translation was edited very freely, and the editor Mb3 decided to include the second version as well; this follows in Mb much later: between the stories of "Herburt and Hilde" and Walther and Hildegund . The Icelandic manuscripts only offer the “Second Editing” of the Wilzen saga, neither where Mb has the “First Editing” nor where Mb has the “Second Editing”, but after the narrative sections by Velent, Vidga, Ecke and Fasold.

- The content of the “First Editing of the Wilzen Saga”: First report on the fighting between Wilzen and Russians. The Wilzenkönig Vilcinus defeats the Russian king Hertnit, moves into his capital Holmgard (Novgorod) and makes Russia pay tribute. On the way back across the Baltic Sea after the Russian War, his ship is stopped by a mermaid; he goes ashore, where she meets him as a woman and receives a child. The mermaid brings the newborn to the kingdom of Vilcinus, where it grows into a giant under the name of Vadi. Vilcinus hands over 12 farms in Sweden to Vadi. Vilcinus also has a humane but fierce and greedy son, Nordian. After Wilzinus' death, Hertnit succeeds in subjugating Nordian; this, and later Nordian's gigantic sons Aventrod, Etgeir, Aspilian and Viðolfr are subject to Hertnit interest. King of Wilzenland becomes one of Hertnit's sons, Osantrix, while Russia and Poland inherit another Hertnit's son, Waldimar. Hertnit only leaves Zealand to Nordian.

- Osantrix sends two of his nephews on a recruiting trip to see King Melias of Hunaland , which includes today's Westphalian and Lower Saxony areas, to get his daughter Oda. However, the haughty Melias has the recruiter thrown in jail. Osantrix makes use of a ruse (he goes incognito to the court of Melias and pretends to be Frederick, King of Spain) and the strength of Nordian's huge sons. In particular Viðolfr Mittumstangi. (in King Rother , who is the model for courting Osantrix, his name is Widolt with the pole ) spreads such horror that the other giants have to hold him by iron chains, and he is only released in the worst of the fighting. The prisoners are freed, the king's daughter is kidnapped. Osantrix tries on her incognito a silver and then a gold shoe; the shoes fit. Then he reveals himself. The shoe test is unmotivated here; it makes sense in King Rother. Osantrix marries Oda and has a daughter with her, Erka (who later becomes Attila's wife ).

- Mb 39–56 (I, 56–73 & II, 84–105) “Attila's courtship”: The Frisian prince Attila becomes king of Hunaland , the kingdom of the Hunir or Hynir (not “Huns”; however, double letters were spelled in the Middle Ages very irregularly handled) by tricking him into the possession of Wilzenprinzessin Erka (daughter of Osantrix). Attila's advertisement for Erka is structurally similar to that of Osantrix for Oda; in particular, both brides can only be acquired through lists. While Osantrix himself plays the decisive role in his advertising for Oda, Attila owes the success of the advertising largely to the second advertiser he sent, Margrave Roðolfr von Bakalar ; this corresponds to the Middle High German Rüedeger von Bechelaren ( Pöchlarn in Lower Austria).

- Mb 57-78 (I, 73-131) "The story of the blacksmith Velent" has Vadi, the son of King riesische Vilcinus with a mermaid from the forest a son named Velent, the dwarves at the Balve cave is in the forge teaching . After Vadi's death he slays the dwarves, comes to Jutland as a court blacksmith to King Nnung, forges his famous sword Mimung . Nothing has the tendons cut through his feet so that he cannot escape. Velent takes revenge for this by killing the king's sons and processing their skulls into skull cups, from which Nendung drinks without knowing it, and by raping the king's daughter. Velent flees with the help of a flying device constructed from bird wings (like the Daidalos of the Greek legend). On Nidung's orders, Velent's brother Egil, the marksman, has to shoot the man who fled; it comes to Egil's master shot. Egil once had to shoot an apple from the head of his son as a test in order to be accepted by Niden, and to do this he had three arrows to himself, although Niden had only allowed him one shot. When Nothing asked why after the shot, Egil answered frankly that he would have shot the other two arrows at the king if he had hit his child. Now, while Velent flees, Egil has the opportunity to take revenge on Nnung: Velent had agreed with Egil that he should order him to shoot Velent at a blood-filled bladder that Velent fastened under his armpit , shoot to make it look like Egil has done his job. Egil actually hits the bladder exactly. Nothing believes that the blood is Velent's and therefore does not realize that Egil cheated on him. Velent flies away. As he flies away, Velent Nnung reveals his acts of revenge. The son Vidga arises from the connection with the king's daughter, after Nidung's death there is a reconciliation with Nidung's son.

Egils Meisterschuss is directly related to the legend of Wilhelm Tell , which has its source in the Gesta Danorum of the Saxo Grammaticus in the story of the marksman Toko: Toko was forced by the Danish King Harald to shoot an apple off his son's head; the story Saxos von Toko takes place in the 10th century and was written before 1216; the story of the ThS around 1250; the battle of Sempach, in which Wilhelm Tell is said to have fought, was only in 1307. The Swiss chronicler Aegidius Tschudi , whom Schiller used as a source for his Wilhelm Tell , knew the version of Saxo Grammaticus and applied it to the invented Swiss national hero.

The Wilzen saga is linked to Thidrek through the figures of Vidga (corresponds to the hero of German sagas called Witege or Wittich ), Velent ( Wieland the blacksmith ) and Attila .

- Mb 79–95 (I, 131–173) “Vidga's first exit”: Vidga moves to Bern to test herself in a duel with Thidrek, and meets Thidrek's companions on the way, including Hildibrand. He exchanges the wonderful sword Mimung in a duel between Vidgas and Thidrek in order to spare Thidrek's life. Only then can Thidrek win. Hildibrand gives Vidga Mimung back when Thidrek tries to kill him. King Thetmar separates Vidga and Thidrek; Vidga becomes Thidrek's companion.

- Mb 96–107 (I, 174–203) “Thidrek's fights with corner and Fasold”: Thidrek moves out to gain fame, kills corner and wins his brother Fasold as a companion.

- Mb 108–131 (I, 203–250) “From Thetleif the Dane”: Heimir is banished and joins a band of robbers. Thetleif Aschenpuster is introduced, he fights Ingram and Heimir on his way to Thidrek, Heimir returns to Bern, Thetleif becomes Thidrek's husband. There is a fight between Waltari von Wasgenstein and Thetleif. Amlung becomes Kämpe Thidreks. King Thetmar dies.

- Mb 134–146 (I, 253–273) “The Wilzen saga, second part”: Vildiver comes to Thidrek, Herbrand becomes Thidrek's standard bearer, Attila asks Thidrek for help against Osantrix von Wilzenland, Vidga is captured by the Wilzen, Vildiver freed with help Isungs Vidga, Heimir steals Mimung from the unconscious Vidga, who later returns to Bern. Attila praises Thidrek's companions.

- Mb 147–151 (I, 273–281) “The train against Jarl Rimstein”: At the request of his uncle Ermanrik, who reigns as emperor in “Rome”, Thidrek moves against Jarl Rimstein and defeats him; Heimir and Vidga quarrel, the city of Gerimsheim ( Germersheim ) is conquered.

- Mb 152–168 (I, 282–319) “Young Sigurd”: Sigmund, King of Tarlungaland, woos Sisibe of Hispania. She is slandered for having cheated on him and is said to be murdered in the forest for it. However, the two hired killers disagree; Sisibe gives birth in the forest and places the child in a glass mead vessel; the two men get into a fight and bump into the vessel that rolls into the river and drifts towards the sea. Sisibe dies of pain over it. The glass vessel shatters on a bank; a doe suckles the child. A blacksmith, Mimir, who burns coal in the forest, finds the child and raises it. He gives him the name Siegfried (only later do the writers realize that Siegfried in their German sources is the same legendary figure who is called Sigurð or Sigurd in Scandinavia and they switch to this Nordic form). Since this soon becomes so strong that he beats up the blacksmiths and knocks the anvil into the ground, Mimir wants to have his brother Regin, who lives as a dragon in the forest, kill him. Siegfried kills the dragon with a wooden ax and a tree trunk and cooks the dragon meat. Mimir, full of fear, gives him armor and the sword Gram, in order to put him in good shape, and promises him a horse from Brynhild's stud; nevertheless Siegfried / Sigurd slays Mimir. Sigurd comes to Brynhild, who tells him where he comes from, gives him a horse.

- Mb 169–188 (I, 319–350) “The hero show”: Oda, the wife of King Aldrian, falls asleep in the garden, an alb lives with her, this is how the son Hǫgni / Hagen is conceived. Afterwards the same scribe writes the same story again, but Oda's husband is now called Irung; the number of siblings also varies. The heroes at Thidrek's court (Hildibrand, Heimir, Vidga, Jarl Hornbogi, Aumlung, Sintram, Fasold, Vildiver and Herbrand) are introduced.

- Mb 190–225 (I, 354 – II, 37) "Thidreks Zug ins Bertangenland": Thidrek moves against King Isung in Bertangenland. There Sigurd fights for Isung against Thidrek, by means of a deceptive oath Thidrek can use miming in dire need and wins. Sigurd recognizes the fraud, but still voluntarily becomes Thidrek's husband.

II. Narrative sequence: getting married

- Mb 226–230 (II, 37–43) “Sigurd and Gunnar's wedding”: tells how Sigurd got Gunnar's sister Grimhild as a wife and persuaded Gunnar at his wedding to advertise the most beautiful woman in the world, Brynhild. The four of Gunnar, Thidrek, Sigurd and Hogni set out for Brynhild. She is now angry with Sigurd because he broke her engagement (in the ThS report about Sigurd's first encounter with Brynhild, however, no engagement is mentioned). Now that Sigurd is married, she agrees to marry Gunnar. So Brynhild is not lied to in advertising. Even so, she is not happy that Gunnar is supposed to be her husband and refuses to accept him on their wedding night. When he approaches her anyway, she ties him up and hangs him on a nail on the wall. It goes like this for three consecutive nights. Gunnar asks Sigurd to take the maidservant from Brynhild. Sigurd vows to remain silent. Sigurd sneaks into Gunnar's bedroom in the darkness, exchanges clothes with him, overwhelms and rapes Brynhild. But then he pulls a ring from her finger without her noticing. Since her supernatural powers were tied to virginity, she is now as weak as any other woman and will be at Gunnar's will in the future. Sigurd disappears again under cover of darkness. The two swap the clothes back. Nobody notices anything. You travel back to Gunnar's court; Gunnar now rules the Niflungenland together with his brothers Gernoz and Hogni, as well as with Sigurd. Thidrek travels home to Bern.

- Mb 231–240 (II, 43–61) “Herbort and Hilde”: Herbort moves to King Arthur of Britain for his daughter Hild as a suitor for Thidrek, but escapes with the princess, lives with her, kills his pursuers, becomes a duke a foreign king and gains great fame through this. Thidrek wins Gudilinda, the daughter of King Drusian, as his wife. His companions, Fasold and Thetleif the Dane, marry Gudilinda's sisters.

- Mb 241–244 (II, 105–109) “Valtari and Hildigund”: Valtari (Walther) von Vaskastein (Wasgenstein), nephew of King Ermanrik, and Hildigund, daughter of the Duke Iliad of Greece, come hostage to King Attila of Susat. They flee together, Valtari becomes master of all pursuers, including Hognis, who wants to kill him cowardly from behind: Hildigund notices him, warns Valtari, who knocks out Hogni's eye with a boar bone that he has just gnawed off. They come to King Ermanrik, who agrees with Attila with great gifts.

- Mb 245–275 (II, 109–158) “Jarl Iron”: Jarl Iron is the son of King Arthur (Hs. A: Arkimannus ) von Bertangenland. Irons wife is called Isolde (this Isolde has nothing to do with the Isolden of the Tristan saga). Iron's brother is Apollonius of Tyra. Iron is addicted to hunting, during one of the hunts he becomes a prisoner of King Solomon of France. Isolde achieves his release, but dies soon afterwards. Iron moves to Rome as a widower and follower of Attila for a festival of Ermanrik. On the way there he stops at Duke Aki's 'Örlungenschutz'. Aki's wife Bolfriana and Iron fall in love. The Jarl puts a magic ring on Bolfriana. Duke Aki kills Iron, but dies a little later. The widowed Bolfriana marries Vidga Velentssohn. She becomes the mother of the Aumlungen, who later become victims of the Ermanrik ( Aumlungen : in the Middle High German legend Harlungen ; historical: the Amelungen are the ancestors of Theodoric; in the northern area around Bern-Bonn , the Amelungen appear as a people between the Ahr, cf. (H. ) ARLUNGEN in the area of the Roman fort Brisiacum [Bad Breisig], and the Amel).

III. Narrative sequence: downfall and death

- Mb 276–283 (II, 158–169) “Sifka's revenge”: King Ermanrik desecrated his wife in the absence of his previously loyal advisor Sifka. Sifka first causes the king to condemn his sons to death or to send them to death. Then he brings about the death of the Aumlungen nephews. The fortune of Vidgas, her stepfather, is destroyed. Ermanrik compensates Vidga at Thidrek's advice.

- Mb 284–290 (II, 169–179) “Thidreks Flucht”: Sifka incites Ermanrik against Thidrek, Ermanrik moves against Thidrek, Heimir is enemies with Ermanrik, Thidrek flees first to Rodingeir (German: Rüdiger), then to Susat to Attila .

- Mb 291–315 (II, 179–218) “The third part of the Wilzensaga”: describes Thidrek's war journeys against the eastern countries of the Wilzen and Russians.

- Mb 316–341 (II, 218–258) “Thidrek's move against Ermanrik”: Thidrek receives an army from Attila after the intercession of Queen Erka. Even the sons of Attila are entrusted to him. It comes to the battle of Gronsport (old north, also Gransport ) on the Moselle (in the Dietrichepik the raven battle ; raven is the old German name for Ravenna , where Theoderich is buried and the Middle High German hero epic settles this "Ravennaschlacht"). Duke Naudung fell in battle; Attila's sons and Thidrek's younger brother Thether are killed by Vidga's miming , whereupon Dietrich persecutes him but cannot reach him. Thidrek returns to Attila hapless. Again Queen Erka stands up for Thidrek with Attila; he is acquitted of guilt for the death of the sons of Attila. Queen Erka dies. Thidrek continues to serve with Attila.

- Mb 342–348 (II, 258–268) The next part of the Nibelungen saga: “Sigurd's death”: a long time had passed since the two weddings, and the realm of the Nibelungs, with the capital Werniza (in the opinion of most researchers: Worms on the Rhine), King Gunnar rules with his brother Hogni and his brother-in-law Jung Sigurd. The empire flourished largely because of Sigurd's strength and wisdom. One day Brynhild enters the hall in which Grimhild, Sigurd's wife, is already sitting in the high seat and demands that she leave it because it belongs to her alone (a high seat could accommodate two to three people; the argument is therefore solely from Brynhild out). Grimhild replies that this is her mother's seat. Then Brynhild insults her that Sigurd ran after a doe (an allusion to Sigurd's youth in the forest), and that his wife had to step back behind Gunnar's wife. Thereupon she is exposed by Grimhild, who tells her the secret of Brynhild's defloration in front of those present and shows her a ring as proof, which Sigurd Brynhild pulled off when he overcame her. Brynhild is not even particularly surprised: she suspected what had happened and demands Sigurd's murder after the argument with Grimhild, not because Sigurd had helped Gunnar on this point, but because he had betrayed it to Grimhild and thus made her shame public. She complains to Gunnar, Hogni and Gernoz of their suffering and demands Sigurd's death and incites the Niflung against him by pointing out that Sigurd is becoming more and more powerful and could wrest their rule from them. The murder does not need any props (like a little cross sewn onto Siegfried's robe in the Song of the Nibelungs ): it is enough for Hogni Sigurd to thrust a spear between his shoulder blades when he lies down on the ground during the hunt staged for this purpose in order to escape from a stream drink. They carry the body home and throw it to Grimhild's bed. They claim a boar killed him while hunting. “You were that boar,” Grimhild says to Hogni.

- Mb 349–355 (II, 268–275) “Hertnidi's fight with Isung”: Death of Fasold and Thetleif - Valtari had died before Gronsport - Thidrek became more and more lonely.

- Mb 356–394 (II, 275–328) “Grimhild's Vengeance”: In this largest section of the entire saga, there are significantly fewer deviations from the Nibelungenlied than in earlier sections. In places you can clearly see the use of a common template, e.g. B. that Oda (Nibelungenlied: Ute) tells her sons a warning dream about dead birds before they leave for Attila's court. However, there are also significant deviations in both works from their presumed common secondary source. The Attilas court in Susater (= Soester ) is located in the " Hunaland " or present-day Westphalia, not in Hungary as in the Nibelungenlied. According to the predominant research opinion, the ThS is said to have relocated the scenes northwards (see e.g. above on the 'Ravennaschlacht'). Another obvious change to the ThS is that Gunnar is captured by Osid, a nephew of Attila and then, as in other Norse versions of the saga, thrown into a snake tower by Attila. The Gunther of the Nibelungenlied, on the other hand, is defeated by Dietrich von Bern and handed over to Kriemhild. The ThS surely keeps the older version, however, in the fact that Thidrek kills Grimhild on Attila's orders, not Hildebrand single-handedly, as in the Nibelungenlied. Grimhild acts objectively diabolical in the ThS, also in the eyes of the narrator, so that even her husband demands her death, while the Nibelungenlied partially excuses her and Hildebrand does not get the character of an "objective avenger". In the ThS she does not kill Hagen, but her seriously injured brother Giselher by sticking a burning log in his mouth. Attila (corresponds to German Etzel ) is greedy for gold, as in other Scandinavian poems. Hogni was badly wounded by Thidrek, but lives another day until he dies. That night he fathered another son and gave the woman the key to the 'Siegfriedskeller', which she should give to the child when it had grown up. The ThS also does not know a “cook” and therefore does not know “Rumold's advice” from the Nibelungenlied.

In some places the ThS (or its source) apparently not only uses the same template as the Nibelungenlied, but also knows this itself and uses it as a "secondary source". Some formulations of the ThS are more similar to the more recent arrangement “C” of the Nibelungenlied than its original version.

- Mb 395–402 (II, 328–341) “Thidreks Homecoming”: It reports the farewell to Attila, the lament over Rodingeir's death, the meeting with and the victory over Jarl Elsung “from Babilonia”. Thidrek learns that Ermanrik is ill.

From Mb 398 (Thidrek's stay in Bakalar) the spellings based on * Aumlunga-, * Orlunga- / * Ørlunga - are consistently abandoned, also inconsistently in the same chapters of Mb and the AB manuscripts. Beginning with Thidrek's stopover at Duke Lodvijgur ( Hlodver , Mb 403), instead, indicating a joint model by one author , only the forms * Omlunga and * Ømlunga - are used in both the oldest Stockholm manuscript and in the AB texts .

- Mb 403–411 (II, 343–355) “Thidreks and Hildibrand's reception in Bern”: Hildebrand meets his son Alibrand. After the father has defeated the son, they identify themselves, Alibrand hands Thidrek Bern over. Ermanrik dies, Sifka wants to become ruler. Thidrek goes to battle against Sifka.

- Mb 412–416 (II, 355–359) “Thidrek's victory”: Thidrek wins the battle against Sifka, Thidrek ascends the throne at “Romaburg”. Hildebrand and Queen Herrad die.

- Mb 417–422 (II, 359–368) “Thidreks dragon fight”: King Hernit is killed fighting a dragon. His wife, again an Isolde, waits in vain. Thidrek can defeat the dragon, rides in Hernit's armor to his castle and marries Isolde.

- Mb 423–428 (II, 369–375) “Attila's death”: Aldrian, Hagen's son, grows up at Attila's court. His mother informs him of his father's death and gives him the keys to the 'Siegfriedskeller'. Aldrian then avenges Hogni's death on Attila by leading the gold-hungry Attila into the Siegfriedskeller and slamming the door from outside, so that Attila has to starve to death with the treasures. After Attila's death, Thidrek also becomes king of Hunaland .

- Mb 429–438 (II, 375–394) “Heimir and Thidreks end”: Report on the death of these two last heroes. Heimir becomes a monk in a monastery that the old Icelandic manuscripts pass on as Wadhincusan . As monastery brother Lodvigur, he kills a giant who threatens the Premonstratensian Abbey, interpreted as a Westphalian monastery in Wedinghausen . Thidrek finds out about this, takes the only one of the old journeymen who is still alive, and later avenges him by killing another giant who killed Heimir. Soon after, Thidrek is kidnapped from the bathroom by a black steed. The horse is the devil, but Thidrek still manages to call on God and Mary, so his soul can still be saved. The old Icelandic tradition ends here.

Localizations of Dietrichs Bern ("Dietrichsbern")

Dietrichs Bern as the Rhine-Franconian Verona

A considerable part of the older German philology has raised considerable objections to a legendary historical identification of Dietrich von Bern, who is represented primarily in the Thidrek saga and in the Nibelungenlied, with Theodoric the Great:

Franz Joseph Mone blames the original, but insufficiently traditional Low German saga of Dietrich and the Nibelungs, the influence of a high German heroic epic that is gaining ground for the geographical and narrative distortion of Bern and Bonn-Verona . According to his identifications by name, Dietrichs Bern is not far from the seat of the Nibelungs, which he associates with the Neffelbach and other place names in the Voreifel that are apparently related to the legendary material (cf. Heinz Ritter-Schaumburg).

Laurenz Lersch follows the basic view of FJ Mone about the Lower Rhine seat of Dietrich. Lersch concludes that two different legends, one about the Italian Theodoric, the other about a Rhine-Franconian Dietrich in the formative epoch of the German-Italian empire and thus also of the Middle High German literary milieu were interwoven. Lersch also points to coin finds, from whose minting Bonn emerges as the northern Verona , which he wants to apply in the area of the Bonn Minster . To this end, he refers to the legendary writing Passio sanctorum Gereonis, Victoris, Cassi et Florentii Thebaeorum martyrum from the second half of the 10th century, which highlights the Bonn area and the execution site of the martyrs Cassius and Florentius as Verona on the Rhine. He also quotes from an archbishop's deed of ownership issued in the 11th century, which refers to a close connection between Bonn-Verona and Zülpich , which Gregor von Tours suggested as a seat of the first Merovingian Dietrich ( Theuderich I ). Based on the first stanza of the corner song and the geographical information in the appendix to the book of heroes, Lersch recognizes the area between Cologne - Aachen and the Middle Rhine as the native area of tradition of Dietrich's comrades in arms, Fasolt, Helffrich (= Hjalprikr in the Thidrek saga).

After Lersch, Karl Müllenhoff positions a Franconian Dietrich von Bern in the geographically and design-oriented narrative area of Widukind von Corvey , the Quedlinburger Annalen and the old English Widsith . Müllenhoff recognizes in the Wolfdietrich traditions, which he implies as evidence of the literary attraction of East Merovingian history, historical allusions to Franconian rather than Romanesque-Ostgothic conditions. He postulated, therefore, that the spatial and narrative historical consistency of a Austrasian Dietrich Sage (thus I over Theuderich or even his son Theudebert I) was fused with a southern transferred heroic poetry. Joachim Heinzle recently confirmed Lersch's basic point of view about the narrative origin of Wolfdietrich:

"The tradition of Wolfdietrich must be regarded as an independent saga, the origins of which are not to be found in Gothic, but in Franconian history."

According to Hermann Lorenz , the entries of the Quedlinburg annalist on the geographical, figurative and narrative-characteristic milieus of two Theodoriches, the Amal and Hugo Theodericus (Theuderich I.) allow the conclusion that Franconian-Saxon history was interwoven with an already legendary Ostrogothic historiography; see. including Jordanes on " Ermanarich ", whose relationship to an "Odoacer" resettled in the Harz Mountains and that " Attila " who, as a supporter of Theodoric's regaining of his empire, apparently also had access to the Harz region in terms of text interpretation. In this region he is said to have given his blood relative Odoacer, who was exiled, a seat at the confluence of the Elbe and Saale rivers. The annalist notes the child-induced death of this Attila among the entries for the year 531, including the appearance of the Frankish Theodoric (Theuderich I) with his twelve noblest followers among the Saxons, but nowhere is an attack on this "Odoacer ".

In his review of Laurenz Lersch, Karl Simrock rejects the limitation of the Rhenish Verona only to the area of the Bonn Minster, the alleged place of death of the two Theban legionaries and martyrs Cassius and Florentius . Looking at the corner song, Simrock sees the fight between Dietrich and Ecke (as well as later with Fasold), also told by the Thidrek saga, in the Low German area of a Dietrich who originally sat here and not in Italy. Simrock also claims to have recognized the Frankish king Theuderich I as the prototype of this legendary figure. He deduces from the spatiotemporal narrative structures in the Widsith's circle of characters as well as in general agreement with Mone (see above) that

“Two lock picks were too many for the heroic saga, one had to give way to the other and so it hit the Frankish with its legend in the mighty stream of Ostrogothic legends due to the preponderance of the High German language and literature under the Hohenstaufen emperors. "

Karl Simrock and Hermann Lorenz agree with Müllenhoff's view of the representational value and receptivity of the Franconian Hugdietrich and the first Merovingian Theuderich for the Gothic Dietrich saga.

In contrast, Friedrich Heinrich von der Hagen refers in his translation of the Thidrek saga to Italian scenes and thus also to Verona on the Adige as Thidrek's seat. The theologian August Raßmann , who later broadcast this saga , confirms that the High German heroic epic imagines Dietrich's residence in Verona, Italy , however, with some geographical and strategic considerations, points out that for the Thidrek saga one must rather start from Bonn than its seat. Even more clearly than in the translation by FH von der Hagen emerge in Ferdinand Holthausen's dissertation, geostrategically contradicting conditions for the saga locations. In the context of the saga prologue, Holthausen on the one hand uncritically agrees with the geographical localizations of Gustav Storm's Nye studier over Thidreks saga , but on the other hand shows above all interpretable clues for a historical fall of the Nibelung in Soest, Westphalia (cf. Heinz Ritter-Schaumburg). Holthausen quotes its claimed Frisian and Gallic origin from the legally binding statutes of the high medieval Soest: Preterea iuris aduocati est. hereditatem accipere frisonum et gallorum . On this basis, Holthausen combines the intertextual origin of the apparently anachronistic “Attila” with narrative parallels to the chronically written Frisian story of Suffridus Petrus (Sjoerd Pietersz), who, just as controversial as his literary successor Martinus Hamconius (Maarten Hamckema), of one of the Friesenführer Odilbald reported the capture of Soest, dated to the year 344. However, Willi Eggers only agrees with Holthausen that the statements by Petrus (and Hamconius) are compatible with no more than a “preliminary stage of the Soest local saga” or its “founding saga” after the Thidrek saga. These Frisian chronicles, which are largely apocryphal due to their early historical depictions, provide not only names of rulers such as Odilbold, Adelbold, Adelbricus, Adelen but also historically verifiable rulers such as B. Adgillus or Aldgisl.

In terms of text content, there is no explicit information about Thidrek's family seat as to whether the source material that came to Old Norway refers to Bonn as Verona on the Lower Rhine or the place of the same name on the Adige. Even assuming a literal translation of the source, the interpretive leeway for the localization of Dietrich's seat remains unclear for the Nordic scriptors; especially because the dating of the oldest equation of Verona with Bonn on an altar panel donated for the Pantaleon Church in Cologne (second half of the 10th century) correlates conspicuously with the Lower Rhine edition of the Thebaic legend. The equation on this altar panel is viewed critically by Wilhelm Levison and Theodor Joseph Lacomblet . They refer to the historical context according to which the inscribed Archbishop Bruno (a son of Emperor Otto I ) received part of his training in the diocese of Verona in Italy and later supported Bishop Rather who was active there. Due to this relationship, Lacomblet does not want to rule out the possibility of an Italian name sponsorship. Levison also sees no reason to use this table as a basis for evaluation at all, since the Verona on the Adige can just as well be meant here . Both views were rejected as insufficient arguments by the Bonn historian Josef Niessen, who, on the other hand, favored the weight of numismatic equations on the one hand and documented equations that can be proven repeatedly on the other. The best-known equations from the High Middle Ages, which can be assumed to be received from the 10th century, can be found in the Bonn city seal (13th century), in the Cologne royal chronicle Chronica regia Coloniensis and in Gottfried Hagen's rhyming chronicle of the city of Cologne from 1270, in which various references to Dietrich von Bern .

However, if the source from Lower Germany did not provide any clear geographical information about Thidreks Bern for its writing at the Bergenser Hof, then their scriptors could have an interpretive freedom up to Ostrogoth areas or otherwise supplement it presumptively; as this can be inferred mainly from two passages: the final movement of Mb 13 (Bertelsen I, 30–31) and its introductory repetition in Mb 276 (Bertelsen II, 158) about the empire of Erminrik, which with such a claim neither a contemporary of the great Ostrogothic or a Frankish Theodoric. Especially these two passages in the manuscripts that ethnically it, but not genealogically registered Amali , the separately authored Saga Prologue as commenting supplement as well ostgotisch-Roman Tell milieu producing Middle High German Dietrichepik led the majority of scientific research to the conclusion, behind the figure of the Thidrek only to establish the Ostrogothic Theodoric or, in the absence of their equation, which has not yet been conclusively shown, to assume. According to the views of older German philology (see above) and representations of the saga that can be indexed in terms of content, a Low German model of a Rhine-Franconian Dietrich historia could well - as far as the texts project the personified spatial image of Erminrik (cf. Roswitha Wisniewski, William J. Pfaff et al) with additions from Ostrogothic traditional milieu, for example also by inserting the paternal name of the Italian Theodoric, in Old Norway or, at the editorial discretion of the latter, emended.

A Rhenish Franconian Dietrich vita as a prose work in or from Carolingian bibliography cannot be proven. To that of Charlemagne arranged transfer of Theodoric Reiterstatue of Ravenna in the Aachener Imperial Palace are different interpretations to say historical associations. Although Walahfrid Strabo, under Karl's son Ludwig the Pious, wrote his 23rd and, to that extent, exceptionally critical to derogatory poem De imagine Tetrici , transferred by name to a Germanic-Franconian Dietrich, Felix Thürlemann points out that above all Heinrich Fichtenau and Walter Schlesinger developed the thesis according to which the “architectural quote” had less of a religious significance for Karl than “a function in the context of the (political) ideological competition between the Franconian Aachen and the Italian Rome. Aachen should also present itself externally as a Roma secunda and thus make it visible that Roman rule had passed to the Franks. "

Kemp Malone sees in the Theodoric statue , which was captured by Charlemagne and the rune stone erected by Rök at the same time (apparently in the early 9th century), rather the coincident reference to the heroic figure of a Frankish Theodoric (= Theuderich I) for Dietrich von Bern in the Old Norse Hero poetry and to that extent also for the Thidrek saga. Malone refers to the inscription

“Raiþ Þiaurikr hin þurmuþi, stiliR flutna, strąntu

HraiþmaraR; sitiR nu karuR ą kuta sinum,

skialti ub fatlaþR, skati Marika.Dietrich the brave, ruler of the sea, (and) the beach of

the Hraidmeer, now sits armed on his horse,

the shield tightly tied, Prince (husband) of Marika. "

According to Malone, also on the basis of an alternative identification of the Mæringer , the destruction of a Godland (and thus not "Gothic") maritime campaign led by Theuderich's son Theudebert I under their leader Hygelac (in the first quarter of the 6th century) should be carried out by the Northern countries have experienced a lasting reminiscence. William J. Pfaff quotes the editor of the Hervara saga on the Old Norse idea of the Hreiðgotaland at HraiþmaraR : He þat says, at Reiðgotaland ok Húnaland sé nú þýðskaland kallat. From the point in time when the immediately preceding rune moves Þat sakum ąnart, huaR fur niu altum ąn […] - “That I say second, who nine generations ago […]” - Malone goes to identify or roughly backdate this battle from this period out.

Dietrichs Bern as an Italian term

As is already expressed in the saga prologue and also essentially in the majority research opinion, the Old Norse text conception is intended to reflect an apparently Romanesque or Ostrogothic milieu for the title figure of the Thidrek saga, which is supposed to be based in Verona on the Adige. In addition, however, William J. Pfaff also takes into account the possibility that forgotten traditions about the end of the Nibelungs in that " Attila ", which was given the death story "Aldrian's Rache" (Mb 423–428, Bertelsen II, 369–375) northern spatial milieu, according to which later German poems even place Þíðrikr at Bonn because the town had been known as Verona Cisalpina in earlier times. With Bertelsen's transcriptions of the narrative sections according to II, 43–46 (AB versions for Mb 231–232) with the local terms Weronni and Iverne, Pfaff also considers that especially the first form, if not an error for Verona in Italy, may reflect a German localization of the story in Bonn ( Verona Cisalpina ).

Thidrek's end from Mb 438 (Bertelsen II, 392) must also be added from the old Icelandic manuscripts, with an obvious allusion to those two reliefs on the portal of the Church of San Zeno in Verona and the " Weltchronik " of Otto von Freising (1143–1146, revised 1157) ). He interprets these representations with a popular tradition, according to which Theodoric is said to have gone to hell on a horse. Otto's rejection of his contemporary constellation with the Greutungskönig Ermanarich as well as the Hun leader Attila already allowed conclusions to be drawn about untrue Ostrogothic Dietrich traditions - including the previous criticism by Frutolf von Michelsberg based on the Gothic Chronicle of Jordanes and the author (s) of the essentially adopting Imperial Chronicle to.

It remains unclear whether these authors were able to refer to the oldest text testimony about “Dietrich von Bern”, the Old High German Older Hildebrand song available as a fragment : The special value of this work, probably written around 830 in Fulda Abbey, is particularly evident for text research and the genesis of tradition in Dietrich's archenemy, who is not equated here with the Greutungen ruler Ermanarich , but with Theodoric's historical opponent Odoacer . The presentation of this song, however, contradicts the real historical fact that Theodoric was never expelled from Odoaker, but - blatantly different from the saga - he was finally murdered by Theodoric himself. The Quedlinburg notes, which are closely related to this song in chronological terms and apparently amalgamating two lines of tradition, do not reveal, regarding the figurative context of relationships between their Attila, Theoderic and that Odoacrus , that the Frankish Theodoric ( Theuderich I ) , who performed in Saxony, was once called by a Gallic- Saxon army commander , as Gregor von Tours mentions one such as an Odovaker around 470 in northern Gaul, had already been expelled because of a possible dispute within the Franks.

The further interpretation of an apparently "mythical Dietrich legend", which is mainly based on the Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great, requires considerable concessions to both geopolitical and figurative interpretations for its equation with the Old Norse Thidrek, which is less so than the Middle High German Dietrichdichtung ("Theodorich der Große = Dietrich von Bern ”) rather than contradicting the content of the saga. For example, Thidrek's campaign to recapture the lower Moselle ( Musula ) and the battle at its mouth at Gransport or at “Raben”. However, with less textual agreement, this passage is also reinterpreted as the fighting at the “grandis portus” of Ravenna - the historical residence, which is also the slaughter site “Raben” of the great Ostrogothic Theodoric. It also seems highly questionable whether the saga of those Witichis (from 536 to 540 king of the Ostrogoths) as the archenemy persecuted and later killed by Thidrek (cf. old Swedish texts) can be demanded. Another significant disproportion exists for the interpretative inclusion of the Ostrogothic Amal dynasty, which the source texts only represent as a tribe and therefore cannot be reconciled with the grandfather's "Hispanic" origin of Thidrek.

A name correspondence with his father “Theodemir” , but not with his father and all forefathers, can be shown in the saga for Theodoric's origin . However, according to the information provided by Gregor von Tours and the pseudonymous Fredegar, a Théodomer can be identified in the early Franconian royal series as well as an earlier Þettmar in the saga , cf. Mb 9 (AB manuscripts) or Bertelsen I, 23. Accordingly, there are comparable ancestral relationships with the first Merovingian Theodoric as well as with Thidrek on a great-grandfather level, but with different genealogical-name interrelationships.

A fundamental problem of interpretation lies in the obviously directional relationship of dependency between contemporary Latin chronicles about the Ostrogothic Theodoric and his transmission into the heroic epic as the Thidrek depicted in Old Norse. The initiation of this procedure should therefore have been reserved for a group of scholars who knew how to avoid the blatant disparities in the vitae of the real-historical and epized Theodoric, because

- Heroes 'songs, as they serve to preserve the memoria of great kings and warriors in oral or semioral societies, are in principle also attested for the Goths through Jordanes' ‹Getica› (probably 550/551), but not for Theodoric.

Elisabeth Lienert notes that only Ennodius created a panegyricus about him in 507, but in Latin .

In this respect, Joachim Heinzle, especially regarding the opposing escape constellations, the extremely distinctive biographical stigmata of Dietrich – Thidrek and the Ostrogothic Theodoric, is by no means uncritical:

- The main thing remains a mystery: how Theodoric's historical conquest of Italy was transformed into the expulsion of Dietrich from Italy.

Nibelungen and Thidrek saga

Several episodes of the Thidrek saga, interrupted by other narratives, deal with the Nibelung saga , whereby the Nibelungs are consistently referred to here as the Niflungs. As Roswitha Wisniewski has shown with text synoptic examinations of the Thidrek saga and the manuscripts of the Nibelungenlied, including its so-called "Lamentation" and a postulated "Notepos", the authorship of the Thidrek saga used this Upper German heroic poem for character names and a series of scenic plot sequences but the core content is a template material that can be summarized under the term of a second source , including those Soest depictions of the Niflunge. Not inconsistent with this, Joachim Heinzle z. B. on Thidreks, Herrads and Hildebrand's march back from their exile to Bern states that both the Thidrekssaga and the Nibelungenklage report that the three made a stop in Bakalar / Bechelaren, and both stories emphasize the fact that they took a pack horse. It is unlikely that the reports are completely independent of one another, but one cannot say whether they are based on a common legacy or whether the “Thidrek Saga” writes out the “Nibelungen Lament”.

The differences between the Thidrek saga and the other Nordic versions ( Liederedda , Snorra Edda , Vǫlsunga saga ) are even greater . For example, Brynhild, who is portrayed as the Amazon-like queen from distant Iceland in the Nibelungenlied, is initially mistress of a place called Seegard ( Sægard ) in Svava (which does not necessarily mean today's Swabia - there was also a Svava in Carolingian times ) in the Thidrek saga -Gau in East Saxony). There she has a famous stud, from which the battle stallions of the most famous heroes come; also the Ross Sigurd (which he receives from her). In addition, she is deflowered by Sigurd (= Siegfried) - in the Nibelungenlied, Siegfried only helps King Gunther to conquer the unruly Brünhild on the second wedding night so that Gunther can have sexual intercourse with her. This is quite different in the rest of the Old Norse tradition: there Sigurd advertises in Gunnar's (= Gunthers) figure to Brynhild, because he cannot overcome the obstacles (wall of flames) on the way to her, but lays on the following night, which is his wedding night must spend with her, his sword between the two, in order to keep her virgin for the friend.

In the Thidrek saga, Brynhild demands Sigurd's killing because Sigurd told Grimhild the secret of the bridal night. That she had to marry Gunnar, a hero lesser than Sigurd, is the reason for her refusal on the wedding night.

Differences to the Upper German Dietrichepik

In contrast to the Middle High German Dietrichepik, Dietrich's figure in the Thidrek saga is drawn less positively. His hesitation, e.g. For example, struggling with a corner seems to be more a result of fear than - as in the Upper German corner song, based on morally founded deliberation. He defeats Siegfried - as in the rose garden in Worms , but only with a ruse that enables him to use Vidga's miming, a ruse that makes him appear unfair and Siegfried as someone who has been betrayed. In contrast, the figure of Vidga is drawn much more positively than the traitor Wittich corresponding to in Middle High German poetry . In the opinion of some, it does not speak in favor of Thidrek that he repeatedly supports Heimir, who temporarily joins a band of robbers, and takes him back to court after he was the robber captain of Thetlef the Dane (in Middle High German: Dietleip von Stîre [Steiermark ]) was defeated. But one can also see Thidrek's advantage in this, who accepts his followers again when they return repentant. Dietrich / Thidrek is the ideal of a follower who is unconditionally committed to his followers. Its popularity in medieval poetry is essentially based on this. His tragedy is that the rivalry among heroes ultimately prevails and his efforts to keep the group together fail.

According to some researchers, the motif of the devilish black horse, which Thidrek abducts from the bathroom at the end, comes from the aversion of the Catholic Church to the Arian Theodoric. It was changed in the German lockpick poetry in order not to let the exemplary hero go to hell; similar in the Thidrek saga: in the Icelandic version Thidrek calls on God and Mary and can therefore be saved; In the old Swedish version, the kidnapping by a black horse is just a ruse of Didrik to investigate Wideke without being recognized.

Even though the saga apparently begins much further south - Dietrich's ancestor, Samson , rules Salerni (old Swedish version: Salerna in Appolij ), which is usually equated with Salerno and Apulia (or, unlikely, Salurn ), and wins Bern only later - The geographical focus with the Thidreks area of action, with Susat ( Soest ) and the Wilzenkampf, has been shifted more to the north. This leads to geographical ambiguities, which, however, can be resolved with Bonn- Verona, which is already located in ancient philology as the legendary Bern, the Belgian Hesbaye as Samson's Hispania and the southern Dutch high moor area de Peel in the Salian catchment area of the 5th century. Another coherent northern spatial image is shown e.g. B. in the episode about the Jarl Iron, whose residence is called Brandinaburg (Brandenburg?), But who can hunt in the neighboring Valslongu forest, which was "located to the west of Franconia" . Jarl Irons seat should therefore be more in the west. The old Swedish version only mentions Brandenburg in this context .

The main difference lies in the form and its literary genre . There is no prose story based on the Norse biography of Thidrek or Dietrich von Bern, neither in an Upper German tradition nor in a large work in Low German, which, however, advocates parts of the source text research as missing translation templates of the Thidrek saga (see classification of the Thidrek saga ). Traditionally, it is most closely related to the old Norwegian Karlamagnús saga (13th century), the French prose Lancelot (probably shortly before the Thidrek saga, first third of the 13th century) and Sir Thomas Malory's Arthurian novel Le Morte Darthur (1469–1470, Published in 1485). The Rhenish Karl compilation Karlmeinet (around 1320) is also later and of lower quality than the Thidrek saga and also in verse form. It is a hallmark of the 13th century translations of German and French works into Norwegian that the verse form of the originals is converted into prose.

Narrative parts of the Thidrek saga compared to the Middle High German Dietrichepik

As Joachim Heinzle already remarked on the comparably best-known epics of Dietrich's Flucht und Rabenschlacht , older research tried to determine an exact sequence of previous poems. This resulted in true excesses of a rampant reconstruction philology. Because of the unclear preliminary stages, the following overview cannot establish a direct relationship of dependency between the narratives or Middle High German epics cited line by line.

| Thidreks saga | chapter | Dietrichepik |

|---|---|---|

| Hilde Grim episode | Mb 16-17; BI, 34-38 | Corner Song and Younger Sigenot |

| Heimir and Thidrek | Mb 19-20; BI, 40-43 | Alphart's death (echoes in virginal ) |

| Wilzen tradition I Widolf shoe test / knee placement |

Mb 27; BI, 44-49 & II, 62-70 Mb 36-37; B II, 80-83 |

King Rother |

| Thidrek's fight against corner, Fasold |

Mb 96-104; BI, 174-196 | Corner song |

| Thidrek et al. Fasold with Sintram | Mb 105-107; BI, 196-203 | Virginal (Rentwin's Liberation Lines 117-176) |

| Thetleif's train to Thidrek | Mb 111-129; BI, 209-249 | Biterolf and Dietleib |

| Thidrek's procession to King Isung, competitions |

Mb 191-225; BI, 356-II, 37 | Younger Sigenot , rose garden , virginal |

| Herburt and Hilde | Mb 231-239; B II, 43-60 |

Sources of Tristan or Tristan and Isolde , cf. Tristram's saga ok Ísondar |

| Waltari and Hilde | Mb 241-244; B II, 105-109 | Waltharius |

| Dishonor of Sifka's wife | Mb 276; B II, 158-159 | Book of heroes |

| Thidrek's expulsion | Mb 284-290; B II, 169-179 | Dietrich's flight (echoes in Alphart's death ) |

| Gransport | Mb 316-341; B II, 218-258 | Battle of the raven , Dietrich's flight , Alphart's death |

| Hildebrand and Alebrand | Mb 407-409; B II, 348-352 | Younger Hildebrand's song |

| Hertnid of Bergara | Mb 417-422; B II, 359-368 Mb 419; B II, 363-365 |

Ortnit Wolfdietrich |

| Note: B = Bertelsen |

Structure of the saga and conclusions about how it came about

A Low German narrative tradition in the form of a corresponding large-scale model is missing for the Thidrek saga. Therefore, part of the Germanistic and Nordic text research has considered the possibility that the Thidrekssaga is not a translation of a Low German text, but at the Norwegian royal court in the Hanseatic city of Bergen from Lower German smaller forms (more heroic prose than songs) independently according to the resulting ones Norwegian life cycle saga tradition was composed or compiled. Although important prose works such as the Sachsenspiegel and the Saxon World Chronicle were created in the 13th century in the Low German-speaking area , these belong to other literary genres. They show that prose in the Low German-speaking area, in contrast to the Middle High German-speaking area, is considered worthy of literature.

Since, on the other hand, the available manuscripts as well as the old Swedish traditions to be observed in the original context cannot be denied that the text properties are copied, another part of the source research contradicts a work that was largely independently compiled in the old-west Norse milieu from partly orally performed and partly also written heroic songs. In this respect, the source-critical research also postulates a common older and therefore recurrent text version for all available manuscripts, see classification of the Thidreks saga , which, however, can no longer be easily agreed with the local state of Old Norse philology and bibliography due to a considerable part of the content presentations as a translation template .

Conclusions on the content of German source material

With references to some older research articles, Friedrich Panzer shows parallels from the Italo-Norman history of the 11th century to the figure of conquest Samson . However, Hermann Schneider only conceded characteristics that were consistent with the Norman Duke Robert Guiskard and a receptive influence of the Italian Salerno. Schneider, however, negates text-critical assumptions that are based on a Samson Urlied in Lower Germany that also contains French coloring and pleads against the background of the Italian or "Amalic" subordinate saga family von Thidrek for an independently developed saga introductory part.

Hermann Reichert argues essentially against the assumption of a lack of Low German narrative tradition as a major work and template for the Thidreks saga. As he shows in his text-critical investigations into the question of the originals of the Thidrek saga, there are certain common, apparently not random and thus conspicuously indexable additional formulations in the old Icelandic and old Swedish texts, but not in a comparable order of magnitude in the much older Stockholm manuscript. He concludes from this that oral templates are no longer immediate, but rather missing handwriting as the direct source of all available, but at least old Norwegian and old Swedish traditions. Reichert sees this original or its recurrent version (* Th) as a large work of Low German origin consisting of individual sources or narratives, which, according to Heinrich Beck, is "narrative linked" to the Bergensian with Saxon-Danish themes and examples of Old Norse genres Königshof should have essentially been translated. The question of whether this work, which is to be understood as a comprehensive model, was produced in Lower Germany (or Soest) or Old Norway, connects Reichert with the last view of Heinrich Beck, according to which Low German sources should undoubtedly have been conveyed in such a way that, on the one hand, a German one Perspective of the sources presumed, on the other hand in the old Norwegian writing or "creation" an "additional dimension of interpretation", for example the localization of Thidrek's seat, cannot be ruled out.

The partially different linguistic styles as well as some contradicting representations, especially in the oldest manuscript, show the translating activity of editors of different Nordic origins, who obviously used different sources from the German-speaking area, which was repeatedly annotated by hand, and, like the Stockholm manuscript with its five scribes (Norwegians and Icelanders ) has been edited by two main editors (Mb2 and Mb3). The text interpolations of Mb3 ( see above ) relate in particular to Sigurd's youth story and Thidrek's banquet with a subsequent heroic introduction. The interventions by Mb3 in the narrative part of Mb2, which is nevertheless attached in writing, referring to the names of the characters and the number of brothers of the Niflunge, show the editorial access to two different traditions. Another significant example of contradicting duplications concerns the death story about the Wilzen ruler Osantrix, who dies according to Mb2 in the second, but according to Mb3 in the third part of the Wilzen tradition. The old Swedish version of the Thidrek saga, however, does not contain any such contradicting duplications.

Against the thesis of an independent origin in Norway speak those content-related information from which in the Thidrek saga the traces of direct takeovers from written German sources are recognizable, for example when the saga writes "Siegfried" instead of "Sigurd" in several places. In the manuscripts, however, there are not only certain anthroponyms , but also those narrative forms of terms that make an authorship originally suspected in Old West Norse of partly widely spaced, incoherent or unrelated reports open to attack. These include, for example, mentions in the old German gold currency in the stories about Vadi and his son Velent (Mb 58-59; Bertelsen I, 75-77; see also Velents Runensolidus von Schweindorf ), about Velent's son Vidga (Mb 81; Bertelsen I, 136 –138), about Thetleif (Mb 117, 125, 127; Bertelsen I, 221–224, 239–242, 244–245) as well as about Erka's death (Mb 340; Bertelsen II, 254-257). Among the scenic narrative formulas of the Thidrek saga, Helmut Voigt recognized the shoe rehearsal and knee-setting custom in the courtship of Osantrix around Oda (cf. King Rothers courtship for Constantine's daughter) as a German and not Old Norse first creation. In this respect, he concludes about the drafting context:

- That the author of the kneeling of the princess in the Vs. [= Wilzensage] got to know German legal customs on German soil is the most likely and simplest of all possible possibilities.

Willi Eggers addressed the narrative intention of the Wilzen reports, which is related to Low German source material . Eggers recognizes in the first part of the Wilzen tradition (Mb 21-56), in it the takeover of Soest as the capital of the Hunaland by a Frisian "Attila" and his courtship for Osantrix's daughter Erka, a scholarly version from the Soest milieu. Also through the inclusion of the Lürwald as the area of origin of Vildiver's bear dress - the dominant narrative in the second part (Mb 134-146) - and the conquests of important German and later Hanseatic trading centers such as Smalenskia and Palteskia in the third part (Mb 291 –315), Eggers makes a Low German original much more likely than a Wilzen saga for the Vita Thidreks written by Bergensian writers.

The Heime Ludwig story as an allusion to a Low German author

Roswitha Wisniewski recognizes in the story about Heimir in the Wadhincúsan Monastery (Mb 429–435; Bertelsen II, 375–387) an allusion of authorship in this part of the tradition. Wisniewski supplements the walk from Heimir to the Westphalian Premonstratensian monastery in Wedinghausen, which has already been localized by older and more recent text research and is seen as a literary association, with narrative representations that correspond to the Wedinghausen topology and its monastery complex, which was special at the time. As a striking example, she cites Heimir's duel with King Nordian's son Asplian on an island or the Ruhr loop surrounding the monastery area, which has passed down late medieval cartography with river islands. However, since Heimir presented himself incognito to the abbot under the pseudonym Ludwig and only served the monastery community under this name, Wisniewski connects this narrative relationship with the Ludovicus Librarian who performed his literary service in the Wedinghausen monastery in the first half of the 13th century and later also worked in Rumbeck near Arnsberg. This coincidence leads them to the assumption that he not only wrote the monastery story for the Thidrek saga, but also - according to their text-critical considerations as the most likely Low German source - its large-scale model in the form of a Latin chronicle or historia. Concerning the niflung part of the Thidrek saga, she assumes that this template was compiled with other source material as the second source, which is decisive in terms of content, in old Norway. To this end, she cites southern German heroic epics, in particular a postulated preliminary version of the Nibelungenlied ( Notepos or Older Not ), which means that the present genre of the Thidrek saga can be classified less as a chronicle but more as a historia. Hilkert Weddige concludes from Wisniewski's development of the content of the second source :

- Nonetheless, Roswitha Wisniewski succeeded to a large extent in unraveling the contamination in the depiction of the fall of the Niflung: In a precise comparison with the Nibelungenlied, she reveals specific features of a "second" source area in addition to the Elderly Need for the saga. In that, Low German Dietrich poetry and a Historia by Dietrich von Bern, which may have been written down in Wedinghausen Abbey and added with Soester and Westphalian locations, seem to flow together. The method of looking for duplications, the productivity of which Bumke has demonstrated for the model reconstruction of the Brünhild fable, is occasionally overused here, however, because every duplication is systematically traced back to two models, namely to the older need and that second source. After all, it is a common narrative principle of medieval epic.

Wisniewski takes the earliest possible date of origin of a Wedinghausen submission of the Thidrek saga from the dialogue between the abbot and Heimir about the loss of his sword, the Nagelring , as its material was intended for the (re) construction of the church building. With reference to its destruction in 1210, she concludes that the postulated Wedinghausen record was written after this point in time.

In his review of Wisniewski's habilitation thesis, the linguist William J. Pfaff addresses the generic genre of the Thidreks saga from a chronological template material as well as the probability of a Westphalian transmission route from Latin source material to Old Norway. He refers to identifiable Latinisms in the manuscripts, which, incidentally, also suggest a Latin chronicle as a larger-scale model in Bergen , also for the significant Old Norse genre problematic of the Thidrek saga :

- I should agree that a Latin chronicle played a role in the transmission of much of the material in the Thidreks saga. In support of this thesis one might add that some names from sequences unrelated to the fall of the Nibelungs exhibit the peculiarities and variation which were attributed to faulty use of Latin orthographic symbols: for instance, Ruzcia-land and Villcina-land, although in the latter the variants with c , t , z and k are further confused by the possibility that two Slavic words, one with a t , one with a k phoneme, are involved. If these errors are traceable to the same Latin chronicle, a compilation embracing more than the fall of the Nibelungen was assembled in northern Germany in chronicle form.

However, he complains that the scriptors of the AB manuscripts have handed down the Wedinghausen monastery in Langbarðaland, Italy . As notable, but ultimately hardly convincing, Old French and more southern reception motifs, Pfaff has already mentioned the textual intangible Moniage Ogier and the Heymo tradition from the Wilten Premonstratensian monastery. However , Pfaff cannot offer a convincing explanation for Heimir's work in Langbarðaland , Italy , because, according to his source assessments , the original scope of action of Thidrek's follower cannot be reliably opened up using either Nordic or Southern traditions. Since he in no way excludes erroneous translations of less common geographical terms in the Thidrek saga, he comes to the general conclusion that many geographical and legendary errors were certainly made more likely in Bergen than in Westphalia.