Białogard

| Białogard | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Poland | |

| Voivodeship : | West Pomerania | |

| Powiat : | Białogard | |

| Area : | 26.00 km² | |

| Geographic location : | 54 ° 0 ′ N , 15 ° 59 ′ E | |

| Height : | 31 m npm | |

| Residents : | 24,250 (Jun. 30, 2019) |

|

| Postal code : | 78-200 | |

| Telephone code : | (+48) 94 | |

| License plate : | ZBI | |

| Economy and Transport | ||

| Street : | DW163 : Kołobrzeg ↔ Wałcz | |

| DW166 : Żelimucha → Białogard | ||

| Rail route : |

PKP lines: No. 202: Gdańsk – Stargard railway line |

|

| No. 404: Szczecinek – Kołobrzeg railway line | ||

| Next international airport : | Szczecin-Gollnow | |

| Gmina | ||

| Gminatype: | Borough | |

| Surface: | 26.00 km² | |

| Residents: | 24,250 (Jun. 30, 2019) |

|

| Population density : | 933 inhabitants / km² | |

| Community number ( GUS ): | 3201011 | |

| administration | ||

| Address: | ul. 1 Maja 18 78-200 Białogard |

|

| Website : | www.bialogard.info | |

Białogard [ bʲawˈɔgart ] ( German Belgard (at the Persante) ) is a district town in the Polish West Pomeranian Voivodeship . It is also the seat of Gmina Białogard , a rural community surrounding the city.

Geographical location

Białogard is located in Western Pomerania on the banks of the Parsęta River , about 25 km southeast of Kołobrzeg (Kolberg) and 25 km southwest of Koszalin (Köslin), Stettin is about 150 km away.

history

In the 10th century there was a castle on the site of the town, which was an important trading center at the crossroads of trade routes between Poznan - Kolberg and Szczecin - Gdansk (see Białogard Castle ). The first documentary mention was made in 1105 by Gallus Anonymus , who mentioned the white castle that was discovered during the campaign to annex Pomerania to Poland.

The first sign of settlement in the area of the later Belgard is a west Slavic fortified castle on the castle hill, which was built around the 6th century. The first unfortified settlements arose in the immediate vicinity. 200 years later the Pomorans settled here . The fortified castle was then the seat of the local chief and was given the name Belgard, the white castle, because of its protective wall made of white birch.

Duke Mieszko I (around 960-992) had united tribes of the Polans in the area of Warta and the middle Vistula under his suzerainty, which he later extended to the second core area of the Polans in the Krakow region. He and his son Bolesław I (992-1025) later made parts of Pomerania, Silesia and Moravia temporarily dependent on them through conquest. In the course of these conquests, Polanen also stormed the old Pomoran fortifications of Belgard. But Polanen (Poland) never settled here - just as little after their renewed incursions in 1102 and 1107/8, because they were concerned with submission and booty and not with permanent settlement. The repeated incorporation of Belgard and other Pomoran castles by Polish rulers around 1000 and 1100 remained a short episode in the long territorial history of Pomerania. The country around Belgard was called Cassubia .

When handicrafts and trade had developed at the end of the 10th century, the Persante River , on the banks of which the town was located, began to gain importance. It was the transport route for the salt that was extracted in Kolberg to the north . Belgard became a transshipment point and processing place for the important mineral. In the 11th century Belgard became the residence of the Pomeranian Griffin family together with Kolberg. During their incursions in 1102 and 1107/8, the Poles boasted that they had captured Belgard, a rich and powerful city. When Bishop Otto von Bamberg undertook his missionary trip through Pomerania, Belgard was one of his stations in 1124. When Pomerania came under the suzerainty of Emperor Friedrich I Barbarossa in 1181 , Belgard's history as a German city began. The dukes of Pomerania increasingly recruited German settlers, who also settled in Belgard and allowed craft and trade to flourish. In 1299 Belgard was granted the town charter of Lübeck, and in 1307 the town received the stacking license , which created the prerequisite for merchants passing through to offer their goods in town. From 1315 Belgard became a royal seat again when Pomeranian Duke Wartislaw IV settled there. At this time the construction of the Marienkirche and the erection of the city wall began.

In 1469 there was a fight between the Belgardians and Schivelbeiner in the Langener Heide , the cause of which is said to have been a cow from Nemmin . An initially private dispute between a farmer from the Belgarder Land and a neighbor from the Schivelbeiner Land developed into a war between the towns of Belgard and Schivelbein. It was decided in favor of the Schivelbeiner, whereby the Belgardians are said to have lost more than 300 men. This event has been celebrated as a folk festival since 1969.

With the introduction of the Reformation in Pomerania in 1534 and the acceptance of the Evangelical Confession by its dukes and its simultaneous transfer to their subjects, the citizens of Belgium also became Evangelical. They had become so wealthy that the city council had to issue an ordinance against gluttony. The Thirty Years' War put a temporary end to the good times . Imperial and Swedish troops alternately occupied the city and destroyed it considerably. A plague epidemic did the rest to decimate the population by half. After the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 Belgard became part of Brandenburg and in 1714 a Prussian garrison town . At that time the city had about 1200 inhabitants. It housed a cuirassier regiment . During the Seven Years' War , Belgard was occupied by Russian troops in 1760 . A major fire caused severe damage in 1765, which destroyed most of the houses. From the time of the Napoleonic Wars, however, no destruction is mentioned. After the Congress of Vienna , Belgard became a town in the Prussian province of Pomerania and in 1818 the district seat of the district of the same name . In the middle of the 19th century, industrialization started a new boom. New businesses emerged, such as breweries, weaving mills and bleaching plants. The population increased to almost 4,000, which rose again to 7,000 by the end of the century, when further industrial companies for wood and metal processing settled due to the railway connection. In 1898 the city received a gasworks and in 1911 an electric overland switchboard started operations. A barracks was built for an artillery regiment .

The First World War stopped further development in Belgard, even though 11,000 people were already living there after the end of the war. The turmoil of the first years of the Weimar Republic made itself felt in 1920 through the participation of the large farmers located there in the Kapp Putsch . On the other hand, the expansion of the city with new settlement areas in the 1920s had a positive effect. The right-wing conservative character of the city became clear in the Reichstag elections in 1924, when the German National People's Party achieved its third-best result in Germany. In 1933, the National Socialists in Belgard received 61.8% of the vote.

Around 1930 the district of Belgard had an area of 30.3 km², and there were a total of 974 houses in eleven different places in the city:

- Belgard Station (Persante)

- Belgard (Persante)

- Johannishaus

- Barracks and pension office of the municipal hospital

- Kolberger suburb

- Kösliner mining

- Neuendorf

- Polziner dismantling

- Sand mill

- Stadtholz and Lülfitzer Weg

- Uhlenburg

In 1925 Belgard had 12,478 inhabitants, who were distributed over 3,214 households.

The Second World War made itself felt immediately from 1940. The city had to take in evacuees from today's North Rhine-Westphalia, mainly from Bochum, and forced laborers and prisoners of war were added. The first refugees from East Prussia and the Memelland reached the city in autumn 1944, and the number of residents increased from 14,900 in 1939 to a good 20,000 by the end of the war. On March 4th and 5th, 1945, Belgard was captured by the Red Army . At that time, most of the residents were still in the city, as the eviction order had not been given until the evening of March 3, when the Soviet troops were already in front of Belgard.

After the German population remained almost entirely in Belgard and the houses had been plundered by the Red Army and soon also by advancing Poles, the administration of the city was handed over to Polish authorities a few weeks after the end of the war. German property including houses and apartments was confiscated. Immigration from Poland began from the areas east of the Curzon Line that had fallen to the Soviet Union as part of the “ West displacement of Poland ” . Poles from Central Poland and Greater Poland were added later. Due to the Bierut decrees , the German population was expelled from Belgard by the Polish militia between late 1945 and early 1946 . Only a few Germans, who were indispensable for the supply of the city, were detained for some time, as were the Germans who were employed on the goods confiscated by the Red Army and who had to ensure supplies to the military. After 1947, Ukrainians from the southeast of the People's Republic of Poland were also forcibly resettled here as part of the Vistula campaign . In 1950 only 12,700 people lived in the city.

The village of Kisielice with a farm (Przemiłowo) bordering the southern city was integrated into the urban area after 1945.

Development of the population

- 1740: 1,447

- 1782: 1,621, including 32 Jews

- 1791: 1,710, including 27 Jews

- 1794: 1,720, including 27 Jews

- 1812: 1,983, four of them Catholics and 46 Jews

- 1816: 1,972, including eleven Catholics and 56 Jews

- 1831: 2,788, including eleven Catholics and 85 Jews

- 1843: 3,327, eight Catholics and 97 Jews

- 1852: 3,845, including six Catholics and 142 Jews

- 1861: 4,776, including 21 Catholics, 179 Jews and one German Catholic

- 1925: 12,478, including 154 Catholics and 131 Jews

- 1945: 14,345, of which 14,052 Germans, 223 Poles.

- 2015: 24,570

mayor

Since 1517 the mayors of Belgard have been:

|

|

|

Twin cities

- Aknīste (Latvia)

- Albano Laziale (Italy)

- Binz (Germany, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania)

- Gnosjö (Sweden)

- Maardu (Estonia)

- Olen (Belgium)

- Teterow (Germany, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania)

- Caracal (Romania)

- Montana (Bulgaria)

Attractions

- The brick Gothic parish church of St. Mary (Kościół pw. Najświętszej Marii Panny) from the 14th century

- George's Church (Kościół pw. Św. Jerzego) from the 14th century

- the Gothic High Gate (Brama Połczyńska) from the 14th century

- Town hall from the beginning of the 19th century

Personalities

sons and daughters of the town

- Friedrich George Born (1757–1807), German lawyer, First Mayor of Greifenberg and district administrator

- Maximilian Karl Friedrich Wilhelm Graevell (1781–1860), German lawyer, member of the Frankfurt National Assembly

- Heinrich Diestel (1785–1854), German Protestant theologian

- Ludwig Ferdinand Hesse (1795–1876), German architect

- Wilhelm Messerschmidt von Arnim (1797–1860), Prussian major general, most recently commander of the 6th Cavalry Brigade

- Hugo von Kleist-Retzow (1834–1909), German politician, member of the German Reichstag

- Ewald von Massow (1869–1942), German major general and SS group leader, president of the German Academic Exchange Service

- Otto Scharfschwerdt (1887–1943), German trade union official and resistance fighter against National Socialism

- Joachim Utech (1889–1960), German sculptor

- Otto Wendt (1902–1984), German lawyer and politician (GB / BHE), State Secretary in the Lower Saxony Ministry of Economics and Transport

- Hans Martin Schaller (1923–2005), German historian

- Rudolf Waßmuth (* 1928), German agricultural scientist and university professor

- Heinz Busch (* 1931), former German secret service officer, most recently colonel in the Ministry for State Security

- Joe Hackbarth (1931–2000), German jazz musician and painter

- Joachim Neubüser (* 1932), German mathematician, professor at RWTH Aachen

- Adelheid Mette (* 1934), German Indologist and university professor

- Nikola Weisse (* 1941), German actress

- Leonore Siegele-Wenschkewitz (1944–1999), German church historian, director of the Evangelical Academy Arnoldshain

- Joachim Mehr (1945–1964), German carpenter, killed on the Berlin Wall

- Aleksander Kwaśniewski (* 1954), Polish politician, former President of the Polish Republic

- Kamil Skaskiewicz (* 1988), Polish wrestler

Other personalities associated with the city

- Julius Leber (1891–1945), German politician, campaigned for the republic with his unit from Belgard during the Kapp Putsch

- Erika Fuchs (1906-2005), German translator, known as the translator of the Mickey Mouse comics, grew up from 1911 to 1926 in Belgard

literature

- Ludwig Wilhelm Brüggemann (Ed.): Detailed description of the current state of the Royal Prussian Duchy of Western and Western Pomerania . Part II, Volume 2, Stettin 1784, pp. 615-625 .

- Heinrich Berghaus (Hrsg.): Land book of the Duchy of Pomerania and the Principality of Rügen . III. Part, 1st volume: Districts of the Principality of Cammin and Belgard . Anklam 1867, pp. 663-687 .

- Gustav Kratz : The cities of the province of Pomerania - an outline of their history, mostly according to documents. Sänd Reprint Verlag (unchanged reprint of the 1865 edition), Vaduz 1996, ISBN 3-253-02734-1 , pp. 32–38, online .

- Werner Reinhold : Chronicle of the cities of Belgard, Polzin and Schivelbein and the villages belonging to the two districts. Schivelbein 1862, 224 pages.

- Our Pommerland , vol. 14, vol. 11–12: Belgard district .

- Manfred Pleger, 700 years city of Belgard an der Perante, Laboe, 1999

Web links

- Internet portal of the city of Białogard (Polish, German, English, Swedish)

- The town of Belgard (Persante) in the former Belgard district in Pomerania (Gunthard Stübs and Pommersche Forschungsgemeinschaft, 2011).

- Chronicle of the Maaß family with photographs of Belgards 1898–1945

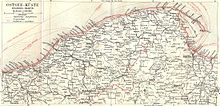

- Historical city map of Belgard, printed in 1907 (PDF; 103 MB).

- Website of the Jewish Community in Belgard (English)

Footnotes

- ↑ a b population. Size and Structure by Territorial Division. As of June 30, 2019. Główny Urząd Statystyczny (GUS) (PDF files; 0.99 MiB), accessed December 24, 2019 .

- ^ Heinrich Berghaus (Ed.): Land book of the Duchy of Pomerania and the Principality of Rügen . III. Part, Volume 1, Anklam 1867, pp. 663-689 .

- ↑ Christian Friedrich Wutstrack (Ed.): Addendum to the short historical-geographical-statistical description of the Royal Prussian Duchy of Western and Western Pomerania . Stettin 1795, pp. 219-221 .

- ↑ Ludwig Wilhelm Brüggemann (ed.): Detailed description of the current state of the Royal Prussian Duchy of Western and Western Pomerania . Part II, Volume 2, Stettin 1784, pp. 615-625 .

- ^ Sieghard Rost: My home in Pomerania. Memories of the land by the sea. Munich / Berlin 1994, p. 143 f.

- ↑ Archive link ( Memento of the original from December 10, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Heinrich Gottfried Philipp Gengler : Regesten and documents of the constitutional legal history of the German cities in the Middle Ages. Erlangen 1863, p. 176 and p. 970.

- ↑ The battle for a cow

- ^ Sieghard Rost: My home in Pomerania. Memories of the land by the sea. Munich / Berlin 1994, p. 146 f.

- ^ Karl Friedrich Pauli : Life of great heroes of the present war . Volume 2, 3rd edition, Hall 1762, p. 271 ( online ).

- ↑ a b c Gunthard Stübs and Pommersche Forschungsgemeinschaft: The town of Belgard (Persante) in the former Belgard district in Pomerania (2011).

- ↑ Helmut Lindenblatt: Pommern 1945. One of the last chapters in the history of the fall of the Third Reich. Leer 1984, p. 205 ff.

- ↑ Helmut Lindenblatt: Pommern 1945. One of the last chapters in the history of the fall of the Third Reich. Leer 1984, p. 205 ff.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Gustav Kratz : The cities of the province of Pomerania - outline of their history, mostly according to documents. Berlin 1865, Vaduz 1996, ISBN 3-253-02734-1 , pp. 32-38, p. 37.

- ↑ Christian Friedrich Wutstrack (ed.): Brief historical-geographical-statistical description of the royal Prussian duchy of Western and Western Pomerania . Stettin 1793, overview table on p. 736.

- ^ Walter Chlebowsky: The municipal administration . In: The Belgard district. From the story of a Pomeranian home district . Published by the Belgard-Schivelbein home district committee in collaboration with the Celle district. 1989, pp. 120-129, here pp. 127-128

- ↑ a b Kronika Miasta 1945–1970, online: website of the city of Białogard (PDF).

- ^ Website of the city, Burmistrz Miasta , accessed on February 3, 2015