The ghost seer

Der Geisterseher ( From the Memoirs of Count von O ** ) is a fragment of a novel by Friedrich Schiller that appeared in several sequels between 1787 and 1789 in the Thalia magazine and was later published in three book editions. Combining elements typical of the time such as evocation of necromancy , spiritualism and conspiracies , the text met the expectations of the reader and brought Schiller the greatest public success during his lifetime. The romantic horror and German-language crime literature were lastingly influenced by him.

In his story, Schiller describes the intrigue of a Jesuit secret society that wants to convert a Protestant prince to Catholicism and at the same time secure the crown in his home country in order to expand its own power base there. With the prince's fate, Schiller illustrates the central conflict between passion and morality , inclination and duty . In the religious and historical-philosophical passages of the work, his ideals of the Enlightenment emerge as a critique of religion and society , which already point to the later intensive occupation with Immanuel Kant .

Because of the slow development and Schiller's aversion to the project, the style and structure of the work are not uniform and range from rhetorically stylized prose to dramatic dialogues reminiscent of Don Karlos to colportage elements in entertainment literature .

content

Narrative situation

The plot is taken from the fictional memoir of the Count of O ** , which is presented to the reader by an editor who, in the first Thalia version, provides comments on footnotes signed with S. In it, the count, as a first-person narrator, describes the story of a prince whom he visits in Venice during Carnival . Right at the beginning, the Count emphasizes that it is an apparently unbelievable incident, of which he himself was an eyewitness and which he wants to report truthfully, because "when these pages appear in the world, I am no longer and will be through the report, which I pay neither to gain nor to lose. ”While in the first book the count is an eyewitness to all important events, in the second part he reproduces the 10 letters of the Baron von F **, who handed him over during his absence from Venice informed of the progress of events.

first book

The prince meets the Armenian

The prince, a reserved, melancholy and serious character closed to his fantasy world, has withdrawn in Venice and believes he can live incognito in this "voluptuous city". He would like to develop freely and without professional obligations, to lead a quiet private life in seclusion and to deal only with intellectual matters. In any case, his limited financial means would not have allowed him to perform according to his rank. So he surrounds himself with a few confidants who are devoted to him. As the third heir, he has no ambition to take over government affairs in his home country.

One evening he and the Count are followed by a masked man, an Armenian, on a walk across St. Mark's Square . He finally reached them through the crowd and whispered some strange words: "Wish yourself luck, Prince ... he died at nine o'clock." He quickly moves away and is not discovered even after a long search. Six days later, the prince learns that his cousin died at nine o'clock on the evening of the eerie encounter. With his death, the prince's prospect of the throne in his homeland increases. But the prince does not want to be reminded: "And if a crown had been won for me, I would now have more to do than think about this little thing."

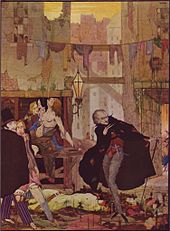

The State Inquisition

The following evening the friends flee from the rain in a coffee house on St. Mark's Square , where some people are playing cards. The prince watches the game until a fortunate Venetian, in an insulting tone, tells the prince to move away. The situation escalates, fights break out and the prince throws the Venetian to the ground. Other Italians band together and leave the house. The guests staying behind warn the prince and advise him to leave the city immediately, as the wealthy and influential Venetian will try to get him out of the world. Suddenly officials of the Venetian State Inquisition appear and ask the friends to accompany them. They are taken to a secret place in a gondola and blindfolded into a vault. When the bandage is removed, they stand in a circle of state inquisitors dressed in black. The Venetian is brought forward. An old man asks the prince whether this is the man who has offended him; the prince affirms. The Venetian, for his part, confesses that he wanted to have the prince murdered. The man is beheaded before the eyes of the terrified prince.

The necromancy

Strange incidents and entanglements lead to the fact that after a long gondola ride over the Brenta the prince with a large entourage, despite many doubts, embarks on a necromancy performed by a dubious Sicilian magician. When asked which ghost he intended to see, the prince chooses that of the Marquis of Lanoy , a friend who had died in his arms from a war wound . Since death had cut the "thread of his speech", the prince would like to hear the "continuation." At the eerie incantation, introduced by thunder and lightning, a pale figure with a bloody shirt appears on the wall of the fireplace, and there is a weak voice to listen. Suddenly the process is interrupted by another clap of thunder and a "different physical figure, bloody and pale like the first, but more terrible" appears and terrifies the magician. While the company is horrified and an English lord attacks the ghost unsuccessfully with his sword, the prince remains calm, recognizes his friend Lanoy and learns in a short conversation what else he wanted to say to him. The prince recognizes the mysterious Armenian in a Russian officer who threatens the magician who is lying on the ground and whose unfathomable face the count had already noticed.

A little later the magician is arrested and his performance is exposed as a deception; the second phenomenon, however, remains a mystery. While the count points out the inexplicability of some phenomena and does not want to rule out the supernatural, the prince insists on a rational explanation and recognizes an intrigue directed against him.

The story of the magician

Although the prince sees through the deception, the events in the further course have a disastrous influence on his nature and behavior. First of all, he manages to speak to the imprisoned magician. He tells him about the sinister Armenian he has met before and who has influenced the fate of a well-known noble family. The Armenian appears in the detailed narration of the magician as a “terrible being.” “There are believable people who remember seeing him in different parts of the world at the same time. No point of degen can pierce him, no poison can harm him, no fire sings him, no ship sinks wherever he is. Time itself seems to lose its power in him. ”. The long account of the magician also includes an internal narrative that deals with a tragic love affair; in it the ghostly Armenian also plays a central role.

Again the friends dispute over the Sicilian's report; the prince rejects everything as implausible and refers to the lower disposition of men as well as to the laws of nature . It is “in the character of this kind of people that they exaggerate such assignments and, through too much, worsen everything that a modest and moderate deceit would have made excellent.” “Would you rather believe a miracle than admit an improbability? Would you rather overturn the forces of nature than put up with an artificial and less ordinary combination of these forces? ”he asks the Count, who replies:“ Even if the matter does not justify such a bold conclusion, you must admit to me that it goes far beyond our concepts. "

second book

The Count is only present in Venice at the beginning and the end of the plot. Ten letters from Baron von F. inform him about the development. However, he himself has only incomplete knowledge of the events, as the prince is increasingly closed to him and is influenced by other people, e. B. from a related prince of ** d **, his new secretary Biondello or the young Italian marquis of Civitella,.

The Bucentauro secret society

The change in the prince becomes more and more evident. The previously modest and reserved person throws himself into wild festivals, lives extravagantly beyond his means and accumulates debts. He joins the ominous society "Bucentauro", whose dark methods the Count thinks he can see through.

In the “bigoted, servile upbringing” and an authoritarian religion in childhood, the count believes he understands the reason for the prince's aberration. "To stifle all the boy's liveliness in a dull mental compulsion was the most reliable means of ensuring the highest satisfaction of the princely parents." So it is not surprising that the prince "seized the first opportunity to escape such a strict yoke - but he ran away from him like a serf slave from his hard master who, even in the midst of freedom, carries around the feeling of his bondage. "The secret society knows how to exploit the prince's imagination and favors" under the outward appearance of a noble, sensible freedom of thought, the most unrestrained license of opinions. "In doing so, the prince forgets" that the libertine of spirit and morals continues to spread in persons of this class precisely because it finds one rein here and is not limited by any aura of holiness ". The members of this society insulted not their class alone, but also humanity themselves through a "damnable philosophy and customs that were worthy of such a leader."

The company boasted of its taste and fine tone, and the seemingly identical equality within it attracted the prince. The witty conversations of members "of the learned and political world [...] for a long time hid the dangerous nature of this connection from him."

The count has to leave Venice and learns the further developments from ten letters of the loyal Baron von F., which form the main part of the second book. Under the impression of the new ideas, the prince lets himself go more and more, runs into high debts and gets to know the easy-going Marchese Civitella .

Philosophical conversation

In the fourth letter, the baron describes a conversation between him and the prince about his financial difficulties due to the lack of a change from court. This seems to be getting more and more unhappy and is fatalistic in the financially troubled situation. At the beginning of the encounter, he complains about his life, his social position and his reputation. As a prince he is the creature of "the opinion of the world". If he couldn't be happy, he couldn't be denied artificial enjoyment. He is obviously in an existential crisis and looking for a higher meaning in his life, which he apparently found at the end of the first part of the novel, surprising for the reader, in his turn to the Catholic religion.

In the long philosophical dialogue that followed this business-private conversation, however, the prince was still convinced of his current moral-philosophical ideas. Influenced by thoughts of the Enlightenment, he postulates an autonomous personality who develops ethical ideas in their soul: "Almost everywhere we can pursue the purpose of physical nature with our understanding in humans." He too is the effect of a cause, but he sees no proof of the “ foreign determination” that the baron demands, and emphasizes the “instinct for happiness [-] of man” associated with “moral excellence”, in which “the moral world [...] creates a new center” so that this like a “state within a state” directs all “its efforts inwardly against itself. [...] What preceded me and what will follow me, I see as two black impenetrable ceilings that hang down at both borders of human life and which no living person has yet raised. Hundreds of generations have been standing in front of it with a torch, guessing and guessing what might be behind it. Many see their own shadow, the shapes of their passion, moving enlarged on the ceiling of the future. "From this limited perspective he derives his thoughts on ethics:" The moral being is [...] in itself complete and resolved [... ] In order to be perfect, to be happy, the moral being no longer needs a new authority. [...] What happens to him must mean nothing to him for his perfection. ”The smaller or larger effect of a morally motivated act is indifferent to its value. People have to work, but are not responsible for the consequences because they are beyond their influence on the chains of events. At the end of the dialogue, the baron points out to the prince the contradiction between his theory and his personal situation: “You confess that man takes everything into himself in order to be happy [...] and you want the source of your misfortune outside yourself search. If your conclusions are true, then it is not possible that you strive beyond this ring with even one wish, in which you keep the human being. ”The prince has to admit this discrepancy between idea and reality.

The conversation, which is structurally reminiscent of a Platonic dialogue , since the baron only acts as a key word, was shortened in the second and third book edition from over 20 to approx. 3 pages.

The beautiful woman

The departure from Venice, which is demanded by the court and which the baron is hoping for, is delayed because the prince falls for a beautiful woman whom he sees in a dark church in the light of the setting day during an excursion to the Giudecca archipelago . He adores her beauty and describes her to the baron with enthusiastic exuberance. "But where can I find words to describe your heavenly beautiful face, where an angelic soul, as on its throne, spread the fullness of its charms?" The prince rejects the word on the baron's simple description that it is about love : “Does it have to be a name under which I am happy? Love! - Don't humiliate my feelings with a name that a thousand weak souls abuse! Which other felt what I feel? Such a being did not yet exist - how can the name be there earlier than the sensation? It is a new, unique feeling, newly created with this new, unique being, and only possible for this being! - love! I'm safe from love! ”In order to enable his further stay and to get to know the woman personally, he accepts the offer of the generous Marchese Civitella and borrows a lot of money. The search for the unknown woman, whom he initially considers an elegant Greek, but who turns out to be a noble German, is unsuccessful for a long time; Finally he meets her on a boat trip from Chiozza via Murano to Venice, the long-awaited conversation, further encounters and an enthusiastic love affair ensue: he only spends his time with the person he loves, and all thoughts revolve around her, that he is like a dreaming walks around and nothing further interests him.

After all, the prince "fell apart with his court" and is severely accused in a letter of leading a dissolute life, listening to "visionaries and ghost banners" and having "suspicious relationships with Catholic clergy." The latter feels misunderstood and slandered and laments his dependence on the regent: There is only "one difference between people - obey or rule!"

The conversion to Catholicism

At the end of the fragment, the count, from whom the baron's last letters had been withheld, learns in a short letter of tragic twists and turns and puzzling events: the Marchese was badly wounded, his uncle, Cardinal A *** i, evidently accuses the prince and hires assassins. The beautiful German of high, presumably illegitimate descent, who therefore has to hide from persecution, is poisoned. On her deathbed she tries to persuade the prince to follow her on the way to heaven, but he resists the wish. Not only the court, but also his sister Henriette refuse to continue to support him financially and justify this with his dissolute way of life and his rapprochement with the Catholic Church: The “church that makes all of it” had “made a brilliant conquest for the prince”.

The baron asks the count to come quickly to Venice to help save the prince. After his hasty trip, however, he finds a different situation than expected: the Marchese has survived and his uncle is reconciled, the debts are paid. The prince does not receive him. The baron, bedridden ill, informs him that he can travel back and that the prince no longer needs his help. He is happy in the arms of the Armenian and is hearing the first mass .

The novel breaks off with the sentence “In my friend's bed I finally found out the unheard-of story”. Many questions from the reader remain open. Various hints in the text suggest that in the further course it should be revealed that the intrigue to which the prince was exposed all the time had gone beyond his personal conversion to Catholicism: it was about the Holy See's influence on a Protestant German To procure principality, in addition, the prince should have been prepared for a crime with which he would have obtained a throne that was not his due.

Emergence

Schiller dealt with the subject for the first time in 1786 in order to obtain new material for his magazine Thalia . The first part of “Geistersehers” appeared in the fourth issue in October 1787, the last in November 1789. The book edition from 1798, which has been published to this day, is a text that Schiller revised three times and redesigned the overall concept twice.

When Schiller wrote the first part in the summer of 1786, he was living in Dresden and corresponding with his friends Christian Gottfried Körner and Ludwig Ferdinand Huber . The enthusiastic Huber supported and accompanied the development process. He translated the “Conspiracy of the Marquise of Bedemar against the Republic of Venice in 1618” and familiarized the poet with Venice and its atmosphere. Schiller's first text about the “mysterious Venice”, written in 1786, is difficult to imagine without Huber's help.

For the ghost seer he interrupted his work on the drama Don Karlos , the motifs of which - urge for freedom, utopia, idealism, conspiracy and intrigues - can also be found in the story, albeit varied. Is it possible in “Don Karlos” u. a. about a “republican conspiracy from the left”, so in the story about a “conspiracy from the right.” Apparently Schiller took up the biography of his friend in his novel and creatively processed it: Körner's youth in the figure of the prince, his mysticistic France experiences with his Paris seducer Touzai Duchanteau, a member of the French Lodge Chercheurs de la Verité , then, as a therapeutic agent for these aberrations, the Kantian philosophy of reason and his proximity to the radical enlightenment communities of the Illuminati and the Freemasons .

After Schiller had moved from Dresden to Weimar in 1787 , he was faced with the question of whether he should continue the novel quickly, which in addition to the good income would have brought him further fame, or stick to a work of history, the "History" begun in 1786 of the strangest rebellions and conspiracies ”. Since he opted for the latter, his interest in the ghost seer initially dried up. He postponed the sequel several times, was plagued by doubts and regretted having embarked on the project. Schiller had initially started his text as a haphazardly written study of charlatans and intrigues and needed an order for the motifs that emerged that he did not believe he could manage. “What demon gave it to me,” he wrote to Körner on March 6, 1788, saying that “the cursed ghost seer” had no interest in him. "The ghost seer, which I have just continued, is getting bad - bad, I can't help." Only with a few activities is he as aware of the "sinful expenditure of time [...] as with this graffiti."

After the audience and the critics reacted enthusiastically to the sequel in the fifth issue of Thalia, Schiller recognized the pecuniary possibilities and decided on a sequel in the form of a large book edition. Even this challenge failed to move him to write more regularly. He finally got the idea to process experiences and philosophical ideas in the novel. This is how the philosophical conversation , which is thematically related to the Philosophical Letters , and the story about the beautiful woman, which appeared in the sixth and seventh volumes, came about. With the philosophical conversation, the project became more interesting for Schiller, as he confessed to Körner. The rich conversation enables him to confront the prince with “free spirit”. Körner, on the other hand, thought the conversation was too long and unnecessary. The conversation deals with skeptical to dark aspects of Schiller's understanding of history and thus differs from the “positive” “inaugural lecture” of 1789. Three book editions appeared between 1789 and 1798. In the second and third editions, Schiller shortened the philosophical conversation.

background

Literary role models cannot be identified. The plot is of a fictional nature, but includes some historical elements.

Count of Cagliostro or Touzai Duchanteau

Although there is no clear evidence, it has been assumed since Adalbert von Hanstein's 1903 study How did Schiller's ghost seer come about that the model for the eerie figure of the "Armenian" was the Italian impostor and alchemist Giuseppe Balsamo, who appeared in Europe as Count of Cagliostro and caused quite a stir with magic tricks and evocations. Schiller processed his spectacular appearances in high society, the effect he had with his tricks on susceptible minds in the scenes of evocations that are described in detail. Cagliostro succeeded time and again in successfully portraying himself as a necromancer at spiritualistic séances. In 1791 he was arrested as a traitor in Rome at the instigation of the Pope . It was believed that he was planning a conspiracy against the Holy See and that he was connected to secret lodges. The circumstantial death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

In his capacity as editor of the Stuttgarter Zeitung "Nachrichten zum Benefit und Genuss" (News for Benefit and Pleasure), Schiller had already learned of the strange occurrences of the case in 1781. In the edition of July 17, 1781 he took over and edited the article "Calliostro" which had appeared in another newspaper a week earlier

Later, Schiller read, in addition to an essay, Elisa von der Recke's book “Message from the famous Cagliostro's stay in Mitau”, published in 1787, in which the “Count” was exposed as a swindler and his activities uncovered.

The dazzling figure of Cagliostro also stimulated the imagination of other poets. During his trip to Italy in the spring of 1787, Goethe visited the Balsamos family to find out more about their origins. His travel notes , published in 1817 , show that he had already dealt with him for a long time. In the comedy Der Groß-Cophta he sketched the ironically broken image of the magician and presented him as a swindler.

Christiane Krautscheid refers to another possible role model for both magical figures: “Körner's seducer from the Parisian period, Touzai Duchanteau. [...] The Armenian resembles much less a charlatan à la Cagliostro than a magical seducer like Duchanteau, who had unusual powers of seduction and a mystical knowledge of human nature and who also had rather relaxed morals. "

History of Württemberg

Like his brothers Ludwig Eugen and Friedrich Eugen , who followed him, Duke Karl Eugen was privately Catholic, but the Duchy of Württemberg as a state was Lutheran under the terms of the Peace of Westphalia ; the heir to the throne, Duke Friedrich Eugen, was supposed to be Lutheran according to the treaty.

A nephew of the Duke, Friedrich Heinrich Eugen Herzog von Württemberg , a Pietist, Rosicrucian and theosophically oriented Freemason, provided Schiller with the material for the tragic figure of the Prince. In July 1786 he published an essay in which he affirmed the existence of ghosts and declared necromancy to be permissible. Like his eldest brother Friedrich Wilhelm Karl , he was raised Lutheran, but came from a mixed marriage of two different faiths: his father, Friedrich Eugen Duke of Württemberg , was Roman Catholic, his mother, Friederike Dorothea Sophia Duchess of Württemberg , née. Princess of Brandenburg [-Schwedt] and Princess in Prussia, like the Brandenburg-Prussian ruling house Hohenzollern, was Calvinist . The entangled, potentially unstable denominational relationships now raised the suspicion that the Jesuits might try to thwart the Protestant succession.

The prince's mother was in contact with Friedrich Christoph Oetinger , who also worked as a translator for the Swedish visionary and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg . A young friend of Oetinger's, Karl Friedrich Harttmann , was Schiller's professor of religion from 1774 to 1777 at the Karlsschule. A nephew of Oetinger, the theosophically oriented Freemason Johann Christoph Dertinger was temporarily rent chamber director in Stuttgart and one of the closest friends of Schiller's father, Johann Kaspar Schiller . On September 24, 1784, he made Schiller aware of Johann Christoph Dertinger's upcoming visit. It is conceivable that Schiller's fragment of the novel was also influenced by this environment. This is supported by the fact that another nephew of Oetinger, Eberhard Christoph Ritter and Edler von Oetinger, was not only a member of the Masonic lodge to the three cedars in Stuttgart, but later temporarily also “superior” (boss) of the Stuttgart Illuminati.

Haunted vision and enlightenment

It characterizes Schiller's work that supernatural appearances only rarely play a role in him and the word ghost in dramas such as Cabal and Love , Wallenstein , Maria Stuart and The Maiden of Orleans is mostly used as a rhetorical stylistic device in the sense of a horror picture, thus in the Usually does not refer to ghosts. Schiller et al. Acquired his knowledge of necromancy. a. from Semler's collections of letters and essays on the "Gassnerian and creative evocations" and Funk's "natural magic".

The Age of Enlightenment promoted the predominance of rationalism, although there was also a "night side" of the Enlightenment, in French, alongside the "Lumières" of the " illuminisme ". The epoch thus offered a rational-irrational hybrid mentality. Rationalism had relegated the occult into the realm of the absurd and often displaced magical elements in favor of a rational explanation. With the advent of romanticism and its turn to the darker side of the soul, this repression seemed to have been overcome.

With the waning of the stimulus that rationalism had exercised within the Enlightenment, the fascination for the mysterious increased and helped it to flourish and dominate again. Since aristocratic circles dealt with table backs and similar phenomena and played with reason, so that the strange could appear self-confidently, new miracle healers who had previously been rejected had the opportunity to stage themselves effectively. People gathered in cities to listen to self-appointed prophets preaching about the end of the world or the return of the Messiah . In Leipzig, the innkeeper Schrepfer achieved a brief fame as a necromancer , and in Saxony and Thuringia the exorcist Gassner made a name for himself.

The fact that Schiller took skeptical positions is shown in discussions he led about relevant fads such as mesmerism and electromagnetic therapy methods. In September 1787 he spoke to Johann Joachim Christoph Bode about Freemasons and methods of magnetic healing , with which he had dealt intensively. After he had completed the first sequel to his novel in May 1788, he allowed Herder to engage in a conversation about media with a reputation for having magnetic powers. While Herder was open to these questions, Schiller reacted negatively. During his time in Heilbronn , he met Eberhard Gmelin , who was one of the most famous followers of animal magnetism . Even after a very long conversation, he was not convinced of the effectiveness of such methods. Compared to Goethe and Schelling, his interest in speculative directions within the sciences and in teaching approaches of the unconscious was limited. Despite many conversations with the enthusiastic Körner, and later with Schelling and Goethe, skepticism dominated, so that his earlier natural philosophical inclinations could not be reactivated.

In his treatise On the Sublime , Schiller explained the fear of night and darkness with dangers that can lurk in them for the imagination four years after the appearance of the spirit seer. The darkness itself is suitable for the sublime and only works “terrible ... because it hides the objects from us, and thus surrenders to us to the full power of the imagination ...” One feels “defenselessly exposed to the hidden danger. That is why superstition puts all ghost appearances in the midnight hour ... "

Arthur Schopenhauer spoke of a rehabilitation of ghosts in his "Experiment on Ghost Vision". He wrote disparagingly of "the super clever past century [of rationalism]", "the skepticism of ignorance" and called those ignorant who doubted the "fact of animal magnetism and its clairvoyance". The metaphysical as well as empirical evidence against the existence of spirits is not convincing. It is already “in the concept of a spirit” that one perceives it differently than a body. The image of a spirit, like that of bodies, also appears in perception ; even if it works without the light reflected from bodies, it cannot be distinguished from the image of a spirit that is seen.

With this, Schopenhauer distinguished himself from Immanuel Kant , who reacted to Emanuel Swedenborg with the dreams of a ghost visionary, which belonged to his pre-critical phase , and who had written mockingly about the "ghost visionaries". The dogmatic metaphysician is therefore like a “dreamer of reason” and does not differ from an enthusiastic ghost seer, since both could mean a lot in their field but prove or disprove little.

Kant did not deny "the madness in such a phenomenon", but did not regard it as a consequence, but rather as a "cause of an imagined community of spirits" and asked provocatively which folly could not be brought into agreement with "a bottomless world wisdom." He does not suspect the reader, "If, instead of looking at the ghost seers in front of half-citizens of the other world, he briefly dispatches them as candidates of the hospital, and thereby overcomes all further inquiries".

The writer Adolph Freiherr Knigge assessed the phenomenon in a similar way to Kant . In his best-known work on dealing with people , he called ghost vision a deception and the "people of this trade" as "mystical deceivers". However, it is a contagious enthusiasm to draw false conclusions from inexplicable facts, to consider deceptions as reality, "fairy tales to be true". If you expose a ghost seer, you shouldn't be afraid to report the fraud in order to warn others.

Secret societies

When the story was written, fantasies about plots, lodges and secret societies aroused the public's interest. The historical background for this was the interplay between the secret societies of Jesuits , Rosicrucians , Freemasons and Illuminati. The Jesuits, banned since 1773, were suspected of using their machinations to induce Protestant heirs to the throne to convert to the Catholic Church. There had been conversions in the family of the Duke of Württemberg: Karl Eugen's father, Duke Karl Alexander, had converted to Roman Catholicism, a fact that Schiller was particularly interested in.

Out of this threatening basic feeling, the genre of the federal novel developed , which was decisively shaped by the ghost Seer Schillers. It was with “comforting horror” that the readers learned of the machinations and conspiracies of elitist secret societies. At the end of the 18th century, more than two hundred relevant works were written , mostly from trivial literature . Schiller too entered this dubious and mystified world with his story, which occupied the European public on the eve of the French Revolution .

Narrative features

With the continuation of the novel, which was announced by Schiller and requested by the readers and critics, he was able to get involved in a financially lucrative serial novel , but decided not to finish the work. In addition to the Abderites by Christoph Martin Wieland, the “Ghost Seer” is one of the works that established this genre. Numerous elements of popular literature such as strange symbols, hints and effects of illusion, false tracks and traces appeal to the curiosity of the reader. The chasing narrative style, in which - especially in the first part - the events roll over and to which the rather short drawing of the secondary characters belongs, drives the action forward.

Perspective representation

In a letter dated February 12, 1789, Schiller described his work as a farce . From this evaluation it follows that his text stands out from the structure of a novel, which is reflected in the structure of the narrative structure. Schiller played virtuously with different levels of reality by allowing various narrators such as the Count of O **, the Baron of F **, the Sicilian magician and the Marchese Civitella to observe the events and report on them from their specific and limited perspective.

Fictionality

The question of authenticity and truth, which is tied to the eyewitness account, played an important role for Schiller. The use of language in fictional speech is characterized by the apparently paradoxical claim to truth of asserting something as real which only applies to the imagined world of the narrative, but not to our reality . With this text the reader knows that it is a matter of fiction, but wants to get involved in the stream of imagination .

Schiller himself went into this (now known) problem of fictional narration by explaining that the reader must conclude a tacit contract with the author in order to let his imagination drift. This enables the poet to disregard the reasonable precepts of probability and correctness. In return, the reader waived a deeper truth check of the event.

The text clarifies the problem of truth and its linguistic mediation and thus also the limits of this special narrative form, which is used in its different varieties up to the present day. When Schiller recognized these limits in 1787, he initially decided not to continue the novel but to deal with scientific historiography.

Bogus authenticity

With occasional comments by the author Schiller, which are marked with the abbreviation “S” in the first Thalia version, the author gives his work a seemingly authentic character. He faked the historical truth by acting like an editor and editing an allegedly traditional script "from the memoirs of the Count of O". Right at the beginning he wrote that he was only obliged to "historical truth" and to report events that he had experienced himself.

The memoir literature had a tradition reaching back to antiquity and, because of its historical distance from current events, had the advantage of being less bothered by the censors . The author, who wrote about his own experiences or specific people and was himself publicly known, vouched for the desired authenticity of this historical writing style . Johann Joachim Eschenburg demanded that the memoir writer "Loyalty and love of truth" as the "sacred duty of historians and biographers", whose "biography is not an ideal novel, but should be based on real facts." This approach can already be found in the first lines of the novel, which Schiller puts it like this: "I am telling an incident that will seem incredible to many, and of which I was largely an eyewitness myself."

The fact that the first-person narrator pretends to be a witness at the beginning of the text in order to vouch for authenticity is a means that was later used in a number of eerie stories, for example by Edgar Allan Poe , HP Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith . To increase the drama and anxiety, the authors often announced that they would have to die later or commit suicide.

Letter form

Despite numerous narrative tricks, the structure of the narrative resembles the simple pattern of a crime story with an uncertain outcome. Of great importance in the second book is the letter form , which was one of the most successful stylistic devices of the time and was used by writers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau , Christian Fürchtegott Gellert ( The Life of the Swedish Countess von G *** ) and Sophie von La Roche . With it, Schiller constructs an often confusing labyrinth of events and exhausts the specific possibilities by always presenting the information bit by bit and coloring it individually. The reader can only vaguely assess the motives of the protagonists, since it is not the main characters like the prince, the Armenian or the cardinal who tell the plot, but only observers. The suspense-creating game of confusion of the ghost seer shows that Schiller, compared to other authors, did not pursue any educational purposes with the letters: he confessed to Charlotte von Lengefeld and her sister in February 1789 that he only wanted to address the reader's imagination and not convey truth.

Significance and interpretation approaches

The ghost seer not only illuminates problems of fictional narration, but also peculiarities of Schiller's representation of history and society.

Schiller's self-assessment

Schiller's stories are less known compared to his other works. Since he only translated a model by Denis Diderot with his text Strange Example of a Female Vengeance and worked with Haoh-Kiöh-Tschuen on a fragmentary novel translated from Chinese, there are only three other stories from his pen besides the ghost seer: Spiel des Schicksals , A magnanimous act and The Criminal of Lost Honor , with which he took up real events.

The aversion to the ghost vision project fits into the self-critical assessment of his prose. He spoke of the novelist as a “half-brother of the poet”, devalued the art of storytelling compared to drama and poetry, and only included the stories The Criminal From Lost Honor and Game of Fate in the first volume of his smaller prosaic writings .

Kantian ethics

The tragic love story, which the cheater sitting in the dungeon tells in dialog form, corresponds to a novelistic tradition. Schiller illustrates the struggle between duty and inclination with the dilemma of the woman who loses her lover through devilry shortly before marriage and is now supposed to marry his initially reluctant brother for reasons of class. This was a fundamental question of ethics that Schiller's influential contemporary and philosophical foster father Immanuel Kant had dealt with in the foundation for the metaphysics of morals and the critique of practical reason .

Schiller dealt intensively with his philosophy and turned to the ethics of aesthetics from the criticism of the power of judgment . Starting from Kant's deontological approach, he considered how the natural inclination could be conveyed with the pure, reason-guided duty .

If the spirit seer still lacked the authority of free will , Schiller dealt further with Kant in the following and, in the treatise On Grace and Dignity , added the image of the beautiful soul to his strict ideal of not following moral maxims out of inclination . In it the natural disposition and the moral law of the categorical imperative coincide by themselves, like nature and freedom in the beauty of art . ( → see Kant and Schiller ).

Political issues

The ghost seer paradigmatically shows some of the then current problems of the European nobility and their environment. On the fate of a prince with an uncertain future in the Republic of Venice , one of the last independent city republics, Schiller not only illustrated behavior typical of the class, but also the dangers to the culture of the nobility.

Bernhard Zimmermann points out the situation of freelance writers who saw themselves exposed to the laws of the market and moved in the field of tension between the exploitation interests of publishers and artistic individuality. Freed from the dependence on courtly patronage and the shackles of class poetics, new possibilities of artistic expression opened up for the writer. On the other hand, they became more dependent on an anonymous reading audience that made decisions about success and failure. Schiller was one of those authors who could not easily adapt to the interests of the bourgeoisie. His feeling for the contradictions of social conditions and upheavals after the French Revolution made him see the ambiguous commodity character of literary works. Schiller wanted to use art to free people from their "self-alienation" and to restore the "whole person in us". After an initial euphoria, he reacted with resignation to the needs of the bourgeois audience. While in 1784 the public was still his sovereign and confidant, after 1799 - under the influence of Kant - he distanced himself from the expectations of his readers. He made a distinction between “favorite works”, genuinely poetic work, and “literary works” that were tailored to the “real” audience. The ghost seer clearly belongs in this category.

For Matthias Luserke-Jaqui , the prince's statement that man is only happy “to be useful” destroys any hope of individual happiness that is now being replaced by a functional value. The prince reacts to this position with a question that is very modern from the point of view of the 21st century: What is owed to the worker who can no longer work, to the person who is no longer needed? There is no answer to the question. The love story with the beautiful "Greek" forms a counterpart to the materialistic philosophy of the prince with its deforming effect on the human character.

Rüdiger Safranski works out parallels to the drama Don Karlos and compares the Marquis Posa with the Armenian. Like him, the marquis wraps himself in a secret and plays with his friend and the queen like with chessmen. Don Karlos, like the prince, would be controlled by a superior, invisible spirit, even if the marquis appears as a figure of light, the Armenian as a dark man. The fact that the prince apparently clears up the intrigue so quickly afterwards turns out to be fatal for him: he relies too much on his mind, believes himself to be safe and proudly and haughtily differentiates himself from his old companions. He loses the bonds that have always been important to him, becomes immoderate and behaves like a libertine who no longer allows himself to be blinded by mysticism, but to whom nothing is sacred either. The Armenian will “free” the prince like a slave who escapes “with a chain on his foot” and is therefore easy to recapture and use for other purposes. He can let himself go in the frenzy of the festivals and accumulate debts. When his soul is finally destroyed and unsettled, he will return to the “strong hand of the church” out of weakness, as is described at the end. A sensitive melancholic becomes a skeptic, free spirit, libertine and repentant sinner. The path leads out of the twilight into the wrong light and back into the darkness.

Character and upbringing

Deviating from his early dramas of Sturm und Drang , Schiller presents the hero as a rather passive, sometimes contradicting personality who is characterized by “enthusiastic melancholy”. The prince appears on the one hand as a quiet and sensitive person who comes to Venice in order to withdraw and realize himself there , on the other hand as courageous and persistent. The ambiguous, even paradoxical peculiarity of his nature is shown, for example, in the fact that he was “born to allow himself to be controlled without being weak”, but nevertheless “fearless and reliable, as soon as he was won.” He is ready, “ to fight a recognized prejudice "and" to die for another. "

The character lacks traits that indicate experience, maturity and self-confidence, which is why he is considered unaffected from the perspective of the educational pedagogy. Too weak to be sure of going its own way or to judge, it can more easily be used and abused for other purposes.

If these characteristics initially appear as a personal and fateful disposition, questions of upbringing will also become clear in the further course of the reading . When Schiller wrote his novel, it was known that a certain imprint on children could also be used for reasons of state. A skillful influence should have an effect in the later power game of the forces, for example to weaken possible competitors of designated rulers. Schiller was familiar with the fate of Philippe I de Bourbon , his brother Louis XIV , who was shaped in such a way that he did not get in the way of the later Sun King. There were also personal points of contact, since Schiller knew the educational methods from his time in the Karlsschule, which were aimed at later representation. The aristocratic ideal of upbringing, which was conveyed, for example, in Castiglione's Il Libro del Cortegiano , demanded, in addition to military virtues, a cosmopolitanism for the nobility, which should be achieved through comprehensive education, an education that was not imparted to the prince despite his background.

The fact that the narrator is rather skeptical of a later correction of certain influences or errors indicates a mechanistic-deterministic model of education. The desperate attempts to clear up the events are ultimately in vain and turn into their opposite: the prince can no longer free himself from the web of uncanny entanglements and the immaturity he is responsible for .

Individual and big city

Like other romantic heroes - Heinrich von Ofterdingen , William Lovell , Medardus and Schlemihl - the prince is also a traveler and meets the memoir writer Graf von O. , who is also en route, in a city that for later writers often becomes the starting point or background of theirs Narratives should be.

Schiller's picture of Venice was influenced by contemporary reports and Wilhelm Heinse's “Ardinghello”, probably also by Le Bret's “State History of the Republic of Venice” from 1769 and his lectures on statistics from 1783. With Venice, Schiller demonstrated his sense of local issues in colportal literature and gave Imagination a playing field on which poets could develop in a foreign sphere, while their own country, according to Rudolf Schenda , did not run the risk of appearing "uncivilized".

Unusual for Schiller, he also addresses the relationship between the individual and the big city in the Ghost Seer and depicts the city in a way that already points to the 19th century and the attitude towards life in the modern age .

The prince, a lonely stranger, “locked in his fantasy world”, roams the alleys and streets “in the midst of a noisy crowd”, a description that is reminiscent of Edgar Allan Poe's The Man in the Crowd and Walter Benjamin's preoccupation with Charles Baudelaire and whose fleurs you remember. In his short story, Poe took up the motif of the cursed wanderer and portrayed a stroller who roams London and never seems to come to rest. For Benjamin, who repeatedly addressed Paris in literary terms, Baudelaire represented the type of the new city dweller, whom he described in his fragmentary work of passage as a melancholy wanderer.

reception

The first part of the story in January 1787 already received a positive response, which, however, did not address the social issues raised by Schiller, but was primarily characterized by an interest in a continuation. In an edition of the Gothaische learned newspaper from June 1787 one read : “An extremely interesting essay, masterfully written. The narrative breaks off where one believes it is close to dissolution. We look forward to the continuation with longing. The editor will certainly be very attached to his readers if he satisfies their tense curiosity as soon as possible. ”Reviewers and the public also reacted enthusiastically to the continuation in the fifth issue and asked for additional parts.

Sequels

Since Schiller did not complete the novel despite numerous requests, but the response from the audience was considerable, many authors tried to continue or imitate it, a trend that began as early as the 18th century and has not been triggered in this abundance by any other German novel. As Gero von Wilpert explains, many of the often anonymous and literarily insignificant works used the traction of the original title, scattered set pieces from the traditional ghost novel and linked this with the political machinations of secret societies.

In them, a simple crown pretender can often be captured by tricks and ingenious stagings and thus increasingly comes under the influence of the deceiver or he relies too much on his mental abilities, because he initially sees through the rip-offs, but later, in the supposed security, easier victims the intrigue will.

The successors that were written during Schiller's lifetime include:

- Lorenz Flammenbergs (d. I. Karl Friedrich Kahlert) The ghost banner. A miracle story (1790)

- Cajetan Tschink's three-part story of a ghost seer . From the papers of the man with the iron larva. (1790–1793)

- Heinrich Zschokke also a three-part work The Black Brothers (1791–1795), Veit Weber's The Evocation of the Devil (1791)

- Georg Ludwig Bechers The Ghost Seer. A Venetian History of Wonderful Content (1794)

- Karl August Gottlieb Seidels The seeress Countess Seraphine von Hohenacker. 3 parts, 1794-1796

- Emanuel Friedrich Follenius' The Spirit Seer . From the papers of Count von O **. Second and third part (1796) as well as Revealed Ghost Stories for instruction and entertainment for everyone. A counterpart to Schiller's ghost seer (1797)

- Johann Ernst Daniel Bornschein's Moritz Graf von Portokar or two years from the life of a ghost seer. From the papers of his friend along with his youth stories. 3 parts, 1800-1801

- Ignaz Ferdinand Arnolds The Man with the Red Ermel (1798–1799), Mirakuloso (1802) and The Night Walker (1802) as well

- Gottlieb Bertrand's Amina the beautiful Circassian (1803).

Hans Heinz Ewers dared a late straggler with the publication of his sequel in 1922.

These attempts could not be convincing from a literary point of view, but their sheer number shows the strong effect of the Schiller's fragment up into the 20th century.

18th and 19th centuries

Many works of horror literature and other genres are inconceivable without Schiller's example. These include ETA Hoffmann's novel The Elixirs of the Devil , Achim von Arnim's Die Majoratsherren or Ludwig Teck's story of Mr. William Lovell . In other stories by Hoffmann - for example in Sandmann and novellas from the Serapion Brothers - there is talk of ghost seers. In his late story, The Elemental Spirit, the protagonist Viktor explains that the penchant for the wonderful and mystical is deeply rooted in human nature. Above all, Schiller's ghost seer seems to “contain the incantations of the most powerful black art itself.” After reading the book, “a magical realm full of supernatural or, better, subterranean miracles opened up for me, in which I wandered and got lost like a dreamer. “Viktor compares the sinister Major O'Malley to Schiller's Armenians .

Another example is the type of the secret society novel , which received numerous suggestions from Schiller's text. In addition to texts that are often satirical or that slide into the trivial, Christoph Martin Wieland's Secret History of the Philosopher Peregrinus Proteus , Jean Paul's The Invisible Lodge , Achim von Arnim's Die Majoratsherren and even Goethe's Wilhelm Meister's apprenticeship with the secret tower society are important representatives of the genre. Not least the effects of the French Revolution increased the interest in rebellions and conspiracies , which was successfully addressed. The fact that Schiller addressed the subject before 1789 shows - as in his dramas - the literary instinct for the great objects of humanity.

20th century

Hugo von Hofmannsthal included the story in his successful collection of German storytellers in 1912 . In the introduction, praised by Thomas Mann , Hofmannsthal Schiller attested to having an eye for “great conditions” and “far-reaching state intrigues”. In the story, "many people are linked in a great fate", and Schiller is able to address the political issue, "almost alone among the Germans", since this side is not their strength.

For Thomas Mann, the influence of the seer on Jakob Wassermann's prose was an example of Schiller's topicality. The question of whether Schiller is still alive is also a "quite German" one and shows a "lack of self-confidence". Schiller's influence can also be felt in modern works, as he wrote on the occasion of a survey in 1929.

In his experiment on Schiller , he described the ghost seer as a "splendid sensational novel". An excited audience assured the author to finish his work. In the novel, however, just as little as in the poetry, Schiller “felt himself to be in his realm” and refused to continue writing. His artist novella Death in Venice also takes place in a city marked by decadence and morbidity. If in the spirit seer it was the beautiful woman, in the novella it is the ethereal boy Tadzio to whom the protagonist falls. If the prince finally indulges in a frenzy of play and despair, Aschenbach's high standards as an artist and performance ethicist are increasingly called into question.

For Rein A. Zondergeld, with his unfinished novel, Schiller created not only one of the main works of the German horror novel, but also one of the most influential works in German fantastic literature . In the English translation, the work has developed into an essential model for the Gothic Novel .

Gerhard Storz pointed out the peculiarity of the ghost seer as a time novel , which, despite its fragmentary character, is "an exemplary representative of its genre" and appears so sudden in terms of subject matter and structure that questions about sources and suggestions would arise. Even if ghost vision and the Cagliostro incident are assumed to be known, a literary model is not apparent to him. If Schiller had published the work anonymously, the interested reader would not easily find the author. On the other hand, for Storz there is probably no other work from Schiller's pen that shows his ingenuity and creative power so clearly and, as it were, naked.

For Benno von Wiese , the material belongs to the field of colportage, while it can be assigned to the intention of the didactic enlightenment and is linked to the tradition of moral narratives of the 18th century. Schiller's prose is inseparable from historical writings and classified as a contribution to contemporary history, while genuinely historical writings are in turn "poetically free designs of true tradition". Because of the documentary nature of the narrative and the poetic part of the historical works, the gap between them is an apparent one. At the beginning of the short narrative A Magnanimous Plot , Schiller had warned that existence “in the real” world could be undermined by the “artificial [...] in an ideal world”, thus opposing an escapist romanticization of the world with his prose agile.

Martin Greiner goes into the entertaining character of the fragment. With all the appreciation of its qualities, one should not overlook the colportage-like elements and should not try to lift the work out of this sphere. The fact that Schiller knew how to entertain shows his talent for poetry. Opposite von Wiese he emphasizes the closeness to the dramatic work: In the first part, Schiller is primarily concerned with the secret remote control of people, which he sees as a “technical study of the playwright”, who moves the characters in his plays across the stage like strings.

Like Greiner, Emil Staiger can not see any significant differences between Schiller's prose and his early dramas. Here, as there, the playwright's will to affect the minds of the readers or listeners dominates all other considerations. The quality of the work is measured by the question of what influence is intended and how it is implemented. For Waldemar Bauer, the different interpretive approaches indicate that the work is bulky in relation to literary formal traditions and categories. For him, the contradictions of the fragment demonstrate the “process-like nature of literature” and are an expression of a broken experience of reality.

For Gero von Wilpert , the ghost seer is probably the most frequently overlooked work of German classical music, which almost completely brought together the worries, ideas and fears of the era. In his opinion, it is not a real ghost novel, as Schiller primarily wanted to depict the political abuse of belief in ghosts, but in doing so, beyond the fears of the reader, expressed a discomfort with the ostensibly rational explanation of the world and indicated ways to deeper truths. He praises Schiller's “sober-lucid narrative style” and “coherent compositional art”, which literary studies have overlooked, and calls the fragment an “unknown masterpiece”.

Rüdiger Safranski speaks of a "romantic novel" that Schiller wrote before that time. Even the interest in Venice is romantic in nature. The poet is the first to have effectively imagined the abyss of the city. The motif of “Death in Venice” begins with the ghost seer, which is continued a little later in Heinses Ardinghello , a work in which Venice appears entirely as the capital of love, lust and death. Later authors would have sent their heroes with Dionysian love fates to Venice again and again.

To Schiller fictitious manuscript of a continuation of Geistersehers it goes into Kai Meyer's novel The Ghost-Seer of the 1995th

literature

Text output

1. Thalia. Fourth issue (1787) - eighth issue (1789). Göschen, Leipzig.

2. Book editions supervised by Schiller:

- Friedrich Schiller: The ghost seer. From the memoirs of the Count of O **. Göschen, Leipzig 1789. ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- Friedrich Schiller: The ghost seer. From the memoirs of the Count of O **. First part. New edition, revised and enlarged by the author. Göschen, Leipzig 1792.

- Friedrich Schiller: The ghost seer. From the memoirs of the Count of O **. First part. Third improved edition. Göschen, Leipzig 1798.

Current issues:

- Friedrich Schiller: The ghost seer. From the memoirs of Count von O ** (after the 3rd book edition). In: Complete works ed. by Gerhard Fricke and Herbert G. Göpfert, 5th volume. Hanser Munich, 1967.

- Friedrich Schiller: The ghost seer. From the memoirs of Count von O *** , Complete Works, Volume III, Poems, Stories, Translations, Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart

- Friedrich Schiller: The ghost seer. From the memoirs of Count von O *** . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1978, ISBN 3-518-04269-6 (first edition)

- Friedrich Schiller: The ghost seer. From the memoirs of Count von O *** . Edited by Matthias Mayer. Reclam, Ditzingen 1996 ISBN 3-15-007435-5 .

Secondary literature

- Peter-André Alt : The ghost seer . In: Schiller, Life - Work - Time , Volume I, Fourth Chapter, CH Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-58681-1 , pp. 567-585.

- Waldemar Bauer: Investigations into the relationship between the miraculous and the rational at the end of the eighteenth century, presented in Schiller's "Geisterseher" , Technical University of Hanover, Diss., 1978, 178 pages

- Klaus Deinet: Friedrich Schiller. The Ghost Seer , Munich, 1981.

- Adalbert von Hanstein: How did Schiller's ghost seers come about ?, Berlin 1903.

- Helmut Koopmann : (Ed.) Schiller manual. Kröner, Stuttgart 2011. ISBN 978-3-534-24548-2 . Pp. 750-753

- Matthias Luserke-Jaqui : Der Geisterseher (1787/89) , A. Francke Verlag, Tübingen and Basel 2005, ISBN 3-7720-3368-7 , pp. 174-179.

- Albert Meier: Not con amore ? Friedrich Schiller's Der Geisterseher in the conflict between art claims and triviality. In: Dynamics and dialectics of high and trivial literature in German-speaking countries in the 18th and 19th centuries. II: The production of narration / Dynamique et dialectique des littératures ‹noble› et ‹triviale› dans les pays germanophones aux XIII e et XIX e siècles. II: La production narrative. Edited by Anne Feler, Raymond Heitz, Gérard Laudin. Würzburg 2017, pp. 213–224.

- Heiko Postma: " To be continued ..." Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805) and his novel "The Ghost Seer" . Hanover: jmb-Verlag, 2010. ISBN 978-3-940970-14-5 .

- Gero von Wilpert : Schiller's »Ghost Seer« . In: ders .: The German ghost story. Motif, form, development (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 406). Kröner, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-520-40601-2 , pp. 151-158.

Web links

- The ghost seer in the Gutenberg-DE project

- The Ghost Seer , read by Karlheinz Gabor, on YouTube

Individual evidence

- ↑ Matthias Luserke-Jaqui , The Ghost-Seer (1787/89) , A. Francke Verlag, Tübingen and Basel 2005, pp 175-179

- ↑ Otto Dann , The Spirit Seer. In: Schiller Handbook, Life - Work - Effect, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, p. 311

- ↑ Peter-André Alt , Der Geisterseher , in: Schiller, Life - Work - Time , Volume I, CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 567.

- ^ HA and E. Frenzel: Dates of German Poetry, Chronological Outline of German Literary History , Volume 1, Classic, Friedrich von Schiller, Der Geisterseher, DTV, Munich, 1982 p. 254

- ↑ Friedrich Schiller, The Spirit Seer. In: Complete Works, Volume III: Poems, Stories, Translations, Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart p. 529

- ↑ Friedrich Schiller, Der Geisterseher , Complete Works, Volume III., Poems, Stories, Translations, Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart, p. 533

- ↑ Friedrich Schiller, Der Geisterseher , Complete Works, Volume III., Poems, Stories, Translations, Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart, p. 541

- ↑ Friedrich Schiller, Der Geisterseher , Complete Works, Volume III., Poems, Stories, Translations, Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart, p. 544

- ↑ Friedrich Schiller, Der Geisterseher , Complete Works, Volume III., Poems, Stories, Translations, Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart, p. 556

- ↑ Friedrich Schiller, Der Geisterseher , Complete Works, Volume III., Poems, Stories, Translations, Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart, p. 575

- ↑ Friedrich Schiller, Der Geisterseher , Complete Works, Volume III., Poems, Stories, Translations, Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart, p. 583

- ↑ a b Friedrich Schiller, Der Geisterseher , p. 587, Complete Works, Volume III., Poems, Stories, Translations, Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart

- ↑ Friedrich Schiller, Der Geisterseher , Complete Works, Volume III., Poems, Stories, Translations, Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart, p. 632

- ↑ Friedrich Schiller, Der Geisterseher , Complete Works, Volume III., Poems, Stories, Translations, Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart, p. 636

- ↑ The Spirit Seer (From the memoirs of Count von O **) . In: Kindlers Literature Lexicon . Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1986, vol. 5, p. 3824.

- ↑ Otto Dann, The Spirit Seer. In: Schiller Handbook, Life - Work - Effect, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, p. 311

- ↑ a b c Schiller Handbook, Life - Work - Effect, Der Geisterseher , p. 312, Metzler, Ed .: Matthias Luserke-Jaqui, Stuttgart, 2001

- ↑ a b Rüdiger Safranski , Schiller or the invention of German Idealism, p. 238, Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich, 2004

- ↑ Christiane Krautscheid: Laws of Art and Humanity. Christian Gottfried Körner's contribution to the aesthetics of Goethe's time . Berlin 1998, p. 45 ff.

- ↑ Joseph C. Bauke: The Savior from Paris. An unpublished correspondence between CG Körner, Karl Graf Schönburg-Glauchau and JC Lavater . In: Yearbook of the German Schiller Society 10 (1967), p. 40.

- ↑ Quoted from: Friedrich Schiller, Der Geisterseher , Complete Works, Volume III., Poems, Stories, Translations, Notes, Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart, p. 1192.

- ↑ Rüdiger Safranski, Schiller or the invention of German Idealism, p. 316, Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich, 2004

- ↑ Peter-André Alt, Der Geisterseher, in: Schiller, Life - Work - Time, Volume I, Fourth Chapter, CH Beck, Munich 2009, pp. 572-573

- ↑ a b Matthias Luserke-Jaqui, Friedrich Schiller, The narrative work, 3.2. Der Geisterseher, S, 175, A. Francke Verlag, Tübingen, 2005

- ↑ Kindlers, New Literature Lexicon, Vol. 14, Friedrich Schiller, Der Geisterseher. From the papers of Count von O **, p. 926, Kindler, Munich 1991

- ↑ Peter-André Alt, Der Geisterseher, in: Schiller, Life - Work - Time, Volume I, Fourth Chapter, CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 573.

- ↑ Christiane Krautscheid: Laws of Art and Humanity. Christian Gottfried Körner's contribution to the aesthetics of Goethe's time. Berlin 1998, p. 49.

- ↑ Schiller, Der Geisterseher, Complete Works, Volume III., Poems, Stories, Translations, Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart, Notes p. 1193

- ↑ See the new research results by Reinhard Breymayer: Between Princess Antonia von Württemberg and Kleist's Käthchen von Heilbronn. News on the magnetic and tension fields of Prelate Friedrich Christoph Oetinger . Heck, Dußlingen, 2010, especially pp. 16, 24 - 28, 48, 50, 60, 52, 64, 71, 74, 80, 226. - On Johann Caspar Schiller's letter, cf. ibid., p. 25; also Schiller's works. National Edition , Vol. 33, Part 1. Ed. By Siegfried Seidel. Weimar 1989, on this the comments ibid., Vol. 33, Part 2, by Georg Kurscheidt. Weimar 1998, p. 100 f. - See also KLL [Kindlers Literature Lexicon (editorial article)]: Der Geisterseher. In: [Helmut] Kindlers Literature Lexicon . 3rd, completely revised edition. Edited by Heinz Ludwig Arnold, vol. 14. Metzler, Stuttgart, Weimar 2009, p. 508 f.

- ↑ Gero von Wilpert, The German Ghost History, Motif Form Development, Kröner, Stuttgart 1994, p. 152

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of Philosophy Occultism , Vol. 6, p. 1143

- ↑ a b Rüdiger Safranski , Schiller or the invention of German Idealism, p. 241, Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich, 2004

- ↑ Peter-André Alt, Der Geisterseher, in: Schiller, Life - Work - Time, Volume I, Fourth Chapter, CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 574.

- ↑ Friedrich Schiller, From the sublime, in: Friedrich Schiller, Complete Works, Volume V, Philosophical Writings, Vermischte Schriften, Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart, p. 184

- ↑ Arthur Schopenhauer, Parerga and Paralipomena, attempt on ghost vision , p. 275, all works, vol. 4, Stuttgart, Frankfurt am Main, 1986

- ↑ Immanuel Kant, Dreams of a Spirit Seer explained by Träume der Metaphysik, p. 952, works in six volumes, Volume 1: Pre-critical writings up to 1768, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1983.

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of Philosophy, Metaphysics , Vol. 5, p. 1252.

- ↑ Immanuel Kant, Dreams of a Ghost Seer explained by Träume der Metaphysik, p. 959, works in six volumes, Volume 1: Pre-critical writings up to 1768, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1983.

- ↑ Rüdiger Safranski, Schiller or the invention of German Idealism, p. 242, Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich, 2004.

- ↑ Peter-André Alt, Der Geisterseher, in: Schiller, Life - Work - Time, Volume I, Fourth Chapter, CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 571.

- ↑ Metzler, Lexikon Literatur, Fiktionalität, Weimar, 2007, p. 240

- ↑ a b Matthias Luserke-Jaqui, Friedrich Schiller, The narrative work, 3.2. Der Geisterseher, S, 176, A. Francke Verlag, Tübingen, 2005

- ↑ So Waldemar Bauer, Investigations on the Relationship of the Wonderful and the Rational at the End of the Eighteenth Century, presented in Schiller's "Spirit Seer" , Technical University of Hanover, Diss., 1978, p. 41

- ↑ Quotation from: Waldemar Bauer, Investigations on the Relationship of the Wonderful and the Rational at the End of the Eighteenth Century, presented in Schiller's "Geisterseher" , Technische Universität Hannover, Diss., 1978, p. 41

- ↑ Friedrich Schiller, Der Geisterseher , Complete Works, Volume III., Poems, Stories, Translations, Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart, p. 527

- ^ Peter-André Alt, Schiller's Stories at a Glance. In: Schiller, Life - Work - Time, Volume I, Fourth Chapter, CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 487

- ^ Peter-André Alt, Schiller's Stories at a Glance. In: Schiller, Life - Work - Time, Volume I, Fourth Chapter, CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 483

- ↑ Matthias Luserke-Jaqui, Friedrich Schiller, The narrative work, 3.2. Der Geisterseher, S, 177, A. Francke Verlag, Tübingen, 2005

- ^ Ernst von Aster, History of Philosophy, Stuttgart 1980, The German Post-Kantian Philosophy, Herder Schiller, p. 295

- ↑ Schiller Handbook, Life - Work - Effect, Der Geisterseher , p. 314, Metzler, Ed .: Matthias Luserke-Jaqui, Stuttgart, 2005

- ↑ Bernhard Zimmermann, "Reading Audience, Market and Social Position of the Writer in the Emerging Phase of Civil Society", p. 539, Propylaea, History of Literature, Fourth Volume, Enlightenment and Romanticism, Frankfurt, 1983

- ↑ Matthias Luserke-Jaqui, Friedrich Schiller, The narrative work, 3.2. Der Geisterseher, 178, A. Francke Verlag, Tübingen, 2005

- ↑ Rüdiger Safranski, Schiller or the invention of German Idealism, pp. 250/51, Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich, 2004

- ↑ Friedrich Schiller, Der Geisterseher , Complete Works, Volume III., Poems, Stories, Translations, Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart, p. 530

- ↑ Waldemar Bauer, Investigations into the relationship between the miraculous and the rational at the end of the eighteenth century, presented in Schiller's "Geisterseher" , Technische Universität Hannover, Diss., 1978, p. 78

- ↑ Waldemar Bauer, Investigations into the relationship between the miraculous and the rational at the end of the eighteenth century, presented in Schiller's "Geisterseher" , Technische Universität Hannover, Diss., 1978, p. 80

- ↑ Waldemar Bauer, Investigations into the relationship between the miraculous and the rational at the end of the eighteenth century, presented in Schiller's "Geisterseher", Technische Universität Hannover, Diss., 1978, p. 85

- ↑ Friedrich Schiller, Der Geisterseher , Complete Works, Volume III., Poems, Stories, Translations, Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart, p. 530

- ↑ Waldemar Bauer, Investigations into the relationship between the miraculous and the rational at the end of the eighteenth century, presented in Schiller's "Geisterseher" , Technische Universität Hannover, Diss., 1978, p. 84

- ↑ Christine Popp in: Kindlers New Literature Lexicon. Volume 2, Walter Benjamin, Das Passagen-Werk. Munich 1989, p. 497.

- ↑ Quoted from: Schiller Handbook, Life - Work - Effect, Der Geisterseher , p. 312, Metzler, Ed .: Matthias Luserke-Jaqui, Stuttgart, 2005

- ^ Gero von Wilpert : The German ghost story. Motif Form Development, Kröner, Stuttgart 1994, p. 157

- ↑ Gero von Wilpert, The German Ghost History , Motif Form Development, Kröner, Stuttgart 1994, p. 158

- ↑ a b Rein A. Zondergeld, Lexikon der phantastischen Literatur, p. 218, Schiller, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt, 1983

- ↑ Peter-André Alt, The Spirit Seer. In: Schiller, Life - Work - Time , Volume I, Fourth Chapter, CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 567.

- ^ ETA Hoffmann, Der Elementargeist, p. 490, works in four volumes, Volume IV, Verlag Das Bergland-Buch, Salzburg, 1985

- ^ ETA Hoffmann, Der Elementargeist, p. 505, works in four volumes, Volume IV, Verlag Das Bergland-Buch, Salzburg, 1985

- ↑ Peter-André Alt, The Spirit Seer. In: Schiller, Life - Work - Time , Volume I, Fourth Chapter, CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 568.

- ^ Hugo von Hofmannsthal, German narrators , introduction. P. 7, German narrators, first volume, selected and introduced by Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Insel, Frankfurt 1988

- ↑ Thomas Mann, Collected Works in Thirteen Volumes, Volume 10, speeches and essays, “Is Schiller still alive?”, P. 909, Fischer, Frankfurt, 1974

- ↑ Thomas Mann, Experiment on Schiller, p. 349, Essays, Volume 6, Fischer, Frankfurt, 1997

- ↑ Quotation from: Waldemar Bauer, Investigations on the Relationship of the Wonderful and the Rational at the End of the Eighteenth Century, presented in Schiller's "Geisterseher" , Technische Universität Hannover, Diss., 1978, p. 6

- ↑ Waldemar Bauer, Investigations into the relationship between the miraculous and the rational at the end of the eighteenth century, presented in Schiller's "Geisterseher" , Technische Universität Hannover, Diss., 1978, p. 6

- ↑ Waldemar Bauer, Investigations into the relationship between the miraculous and the rational at the end of the eighteenth century, presented in Schiller's "Geisterseher" , Technische Universität Hannover, Diss., 1978, p. 6

- ↑ Quoted from: Waldemar Bauer, Investigations on the Relationship between the Wonderful and the Rational at the End of the Eighteenth Century, presented in Schiller's "Geisterseher" , Technische Universität Hannover, Diss., 1978, p. 7

- ↑ Friedrich Schiller, A generous plot, from the latest story. In: Complete Works, Volume III: Poems, Stories, Translations, Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart, p. 455

- ↑ Waldemar Bauer, Investigations into the relationship between the miraculous and the rational at the end of the eighteenth century, presented in Schiller's "Geisterseher" , Technische Universität Hannover, Diss., 1978, p. 7

- ↑ Waldemar Bauer, Investigations into the relationship between the miraculous and the rational at the end of the eighteenth century, presented in Schiller's "Geisterseher" , Technische Universität Hannover, Diss., 1978, p. 8

- ↑ Waldemar Bauer, Investigations into the relationship between the miraculous and the rational at the end of the eighteenth century, presented in Schiller's "Geisterseher" , Technische Universität Hannover, Diss., 1978, p. 9

- ↑ Gero von Wilpert, The German Ghost History, Motif Form Development, Kröner, Stuttgart 1994, pp. 151–152

- ^ Rüdiger Safranski, Schiller or the invention of German Idealism, pp. 245/46, Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich, 2004