Vocal pedagogy

The vocal pedagogy deals with the construction of a for musical use proper vocal technique and with the compound of acquired voting technical skills with the artistic interpretation of vocal music .

Singing lessons are given at public and private music schools , conservatories , music colleges as well as in private lessons and generally take place in individual lessons. Through funding programs, singing lessons in schools are increasingly being given as lessons in small groups or in class groups. Also, community colleges offer singing lessons in groups. For choirs there is the possibility of choral voice training.

history

Antiquity

The first traces of a singing school can be found in ancient Greece . Euripides , Phrygis of Mitylene, Philoxenes of Kythera and Timotheos of Miletus wrote solo pieces that a. characterized by fast and high coloratura . In the solo scenes, Euripides demanded great musical skill, personal expression and style from the singer. These increasingly high demands of the Greek theater led to the need for a specialized school. Singers and dancers formed communal guilds. In Athens was created around 500 BC. The Dionysian Association, which provided actors, singers and musicians with training. It spread rapidly over all of Greece and its colonies as far as Rome. Hadrian formed a world alliance of Dionysian guilds there.

middle Ages

Constantine the Great gave his consent to music in the Christian Church in 325. In 386 Ambrosius brought the St. Basil of Capodocia wrote down rules for Christian-Oriental church chanting to Milan. This Ambrosian chant consisted of well-known hymns and psalms that were taught in the newly founded singing schools in Lombardy. Pope Silvester founded a singing school in Rome that dealt with liturgical church singing. Pope Gregory devoted himself to it with increased attention. The Schola cantorum served as a place of work and accommodation for priest singers and teachers, and the Orphanum also provided training and accommodation for gifted orphaned boys. Women and girls were not allowed to sing in church ( mulier tacet in ecclesia ).

A student's church singing lessons usually lasted four years. Written documents such as sheet music or other instructions were not used, melodies and singing technique were passed on orally. Special emphasis was placed on the beautiful sound of the voice. This was especially true for the cantor who led the responsories . Pope Gregory renewed the liturgy so that a singer should refrain from improvisation and ornamentation . He also promoted the uniform sound of the choir with the remark that a singer should not sing too quickly or too slowly in a choir. The neumes emerged from Pope Gregory's first notes .

Completely trained students moved from Rome to other cities in Europe and founded their own singing schools there. With the invention of the musical notation by Guido of Arezzo , the singers from Rome became more dispensable, and every monastery kept a copy of the antiphon . The boys were also taught according to the Guidonian hand and solmization . Arezzo wrote the first instructions for singing legato :

"The voices must merge, one tone must flow into the other and must not be rescheduled."

Musically new was the polyphony or polyphony that emerged from 850 , through which different voices and texts were set against each other for the first time. New instruments came from the 10th century. to Europe, trumpet , lute , guitar , glockenspiel , fiddle and horn . These instruments and especially those since the 8th century The wind organ introduced from Byzantium , which replaced the previously common water organ, favored polyphonic singing. First instructions for the use of various vocal registers were written down:

“The different voices should not be mixed up in church singing, neither the chest voice with the head voice nor the throat voice with the head voice. Mostly low voices, i.e. bass, chest voices, high voices head voices, the voices in between are throat voices. They should not be mixed up in church chanting, but rather remain separate. "

On the secular side, the singers and troubadours , who had previously roamed freely, formed singers' associations in which the artists of the minstrel held competitions among themselves. From the 13th century on the minstrelsy was bourgeois Meistersinger continued. First roaming around freely as vagabonds , they soon set up their own schools in Augsburg, Mainz, Nuremberg and other German cities. Often biblical texts formed the basis of their favorite songs. The Meistersinger tradition died out at the end of the 16th century.

Renaissance

The increased demands of polyphonic church singing created a need for a general singing school. One of the first Italian schools was built in Naples around 1500, and soon more were to follow. Leonardo da Vinci considered the generation of sound in the larynx and substantiated his theses with practical experiments in which he took the trachea and lungs of a person out of the body and quickly compressed the air-filled lungs. So he could see how the windpipe creates the sound of the voice at its exit. Through his initiative, the importance of the vocal folds and the glottis was soon discovered. Fabricius de Aquapendente mentioned two ligaments in the larynx with a crack in between, which he, like the Italian anatomist Vesac in 1543, called the glottis . In 1562, Camillo Maffei, a Neapolitan doctor, published the first work on the physiology of song under the title Discorso della voce . He deals with posture, breathing and tone, recommends checking the position of the tongue through a mirror and the sound of the voice with the help of the echo and also writes coloratura exercises. The basics of the vocal training that is still valid today can be found here. Since the invention of sheet music printing around 1503, similar typefaces have spread in Italy.

Due to the prohibition of the female voice in the church, church hymn was reserved exclusively for boys and men. The boy's voices naturally lost a considerable amount of height and clarity during puberty . Falsettists could not reach the full height of a boy soprano. A replacement was created by the castrati , who were able to perform amazing vocal performances in the centuries that followed. The clear, penetrating timbre and agility of the boy's voice were retained, plus the strength and fullness of breath of an adult's body. In the 17th century they mostly sang in church music, at masses , motets and madrigals . They would later become the most sought-after virtuosos of opera .

Baroque

The Italian singing schools of the 16th century were converted into conservatories for musical orphans , similar to the medieval Schola cantorum . The teachers were mostly church musicians, singers and composers. According to the report by Pietro de la Valle (1640), this was followed by a clear change in quality in the singing.

“All of these, however, apart from their trills, the passages and a good tone formation, had almost no singing skills. The art of piano or forte singing was alien to them, alien the gradual swelling or graceful waning of the tone ... At least in Rome they had no knowledge of it until Mr. Emilio del Cavalieri introduced the good school of Florence here in his last years ... that's how we hear artists singing in a far more graceful way. "

Emilio de 'Cavalieri and Giulio Caccini wrote in the forewords to their works about the correct type of musical performance. In already existing and newly founded schools, the singers were trained to a virtuosity that delighted the audience. With his Opinioni de 'cantori antichi e moderni (Bologna 1732), Pier Francesco Tosi wrote a work that explained the principles of Italian bel canto for the first time . Giambattista Mancini joined him with his Pensieri e reflessioni sopra il canto figurato (Vienna 1774). All the important principles of Belcanto are recorded in the writings of Tosi, Mancini and Caccini. This high school of old Italian singing gave the singer a never-ending breathing time, great agility, well-managed legato , perfect pronunciation and the same vocal sound in all registers . Good castrati were the highlights of the opera performances and soon became crowd pullers. Opera conquered Italy, new opera houses were built, and both court and bourgeois audiences enjoyed it.

While the Italian school of bel canto soon spread throughout Europe and the writings of Tosis and Caccini were translated or used as the basis for more recent works, the art and performance of opera found new followers in England, Germany and Spain. In France, the operas by Jean-Baptiste Lully and Jean-Philippe Rameau were preferred. However, with the increasing art of ornamentation by the singers, the basic musical line of the melody as well as the intelligibility of the text was gradually lost, which was increasingly displeasing to the public in the 18th century.

With his opera reform , Christoph Willibald Gluck put music at the center of the opera again. He did not allow his simple arias to be adorned, but instead enforced the composer's primacy against the singers. He also introduced the orchestral recitatives , increased the effect of the choir and the ballet, thus accommodating the French taste, and often used wind instruments in the orchestra in addition to the strings. In this way he helped the work to achieve a new dramatic intensity, since the aria was no longer a vehicle for the artistry of a singer, but represented human emotions of a character.

The 18th and 19th centuries

The orchestral recitative required the sopranos and tenors, who took the place of castrati, to rethink. Transposing to a more comfortable position, which used to be common, was no longer possible. The parts that were originally written for castrati became unsingable due to unequal biological conditions, tenors and sopranos were not able to cover the same vocal range.

Another new feature was that the voice had to be able to carry across the orchestra. The cast of the orchestra in Gioacchino Rossini's operas was already very large by the standards of the time, which brought his wife Isabella Colbran to an early end. Like her colleagues Maria Malibran and Giuditta Pasta, she sang in the low register with the full use of her chest voice against the orchestra and thus increasingly lost the pitch of her voice, which is proven by the range of Rossini's soprano parts: between 1815 and 1823 he wrote all of his operas for his Wife. In Armida , her part required the three-stroke c, for Semiramis an a or b is rarely required.

After Rossini settled in Paris, his compositional style also changed for the male voices. For the tenors the goal was now to be able to enforce loud and high notes against the orchestra. The first tenor of the Paris Opera, Gilbert Duprez , achieved his high c with the chest voice and thus gave him an extraordinary radiance. From then on he was considered a role model for his emulators and paved the way for the hero tenor's voice. The decline in his vocal skills led him to the teaching profession. He taught at the Conservatoire de Paris from 1842 to 1850 before founding his own singing school.

The ever-increasing enlargement of the orchestra also called for a new type in the female voice. The romantic heroines were now often cast with sopranos who could easily sing across the orchestra - Jenny Lind , Henriette Sontag and Adelina Patti were just as exemplary as Wilhelmine Schroeder-Devrient , who gave the world premiere of Beethoven's Fidelio in 1822 . The contralto were assigned the less important roles of mothers, servants and maids. During this time, the various new requirements and possibilities resulted in further categorizations of the voices, which today form the German system of internationally widespread voice subjects . The voice genres "mezzo-soprano" and "baritone" emerged. In the second half of the 19th century, the demands on the dramatic expressiveness of the voice, especially in the treble, became ever greater. A further complicating factor for the singers was that the mood of the orchestras was always pushed up with the aim of greater brilliance.

For his new type of musical drama, Richard Wagner needed singers who were not necessarily capable of being high, but who were to be extremely durable in terms of endurance. Sometimes the soloists have to sing continuously for half an hour in such a way that they can also be heard over the much larger romantic orchestra . An entire opera can last three to five hours in a row.

New singing schools should clear up the confusion caused by the ever increasing demands on the voice. Yawning, laughing and whispering methods emerged, which initially only increased this confusion.

During this time, however, Julius Hey also invented his singing and speaking theory, which has not lost any of its validity to this day.

Manuel Patricio Rodríguez García was one of the most important singing teachers. He was the first to use a larynx mirror , with which one could take a look inside the throat. His students Pauline Viardot-Garcia , Julius Stockhausen , Johannes Messchaert as well as Salvatore Marchesi and Mathilde Marchesi passed on his teaching.

20th century

Franziska Martienssen-Lohmann , a student of Messchaert, teaches classical singing in Dresden with her student and later husband Paul Lohmann. She promoted young singers in Germany and Scandinavia with her own master classes. Martienssen-Lohmann's essays and books are still considered to be an important basis of vocal pedagogy.

In the age of new music , confident mastery of the vocal apparatus is required more than ever. The sound of the voice itself is explored as well as the sound of the instruments. In addition to the actual singing, there are noises and onomatopoeic utterances, speaking, shouting, hissing, breathing, murmuring, crying, screaming and laughing. In addition, unusual intervals have to be met precisely, which requires a very well-developed tone memory and intonation-safe hearing. In addition, the singer may have to deal with the notation of the works and find out what intentions the signs are based on, where there is improvisational freedom, what role the words play in a work, whether they should be understandable or treated as a vehicle for sound syllables - every work has its specific requirements, which the singer has to deal with intensively.

Singing Pedagogy in Popular Music

In contrast to the traditional school of classical singing, pop singing cannot fall back on such a wealth of experience. However, it is precisely in this area that the training of singers has improved significantly in recent years. There are pop academies of their own and courses of study at universities. In addition, a number of new singing schools have established themselves on the market, which deal with the physiological production of sounds common in pop singing.

Since an essential element in the jazz-rock-pop area is the unmistakability of the voice and the musical listening habits are clearly different, the training of singers in this area is designed differently and based more on individuality. A fundamental technique for this area is belting , in which the chest voice function with the higher proportion of vibrational mass in the vocal folds as the basic color of the voice is expanded and carried upwards - but the position of the larynx is changed, which enables the vocal folds to to ease the tension in the higher pitch.

“Musical singing, especially belting, is uncompromising, extremely honest, as we say in English“ in your face ”. Many doubt whether it is even possible to produce this intense type of singing with a healthy technique. I guess a lot of people just don't like the sound. We are not allowed to judge popular singing by our classical standards. We can safely admit that the human voice is capable of producing various timbres with healthy means. The larynx is not pinned in the throat. Tongue, attachment tube, aryepiglottic sphincter, roof of the mouth, etc., all parts of the voice are extremely flexible. And all types of singing involve dangers. "

Therefore, basic voice training is and remains an indispensable prerequisite for a long-lasting voice. A healthy vocal technique is particularly important in the area of soul and certain forms of pop singing. Whitney Houston and Christina Aguilera demonstrate their technical skills mainly with rich coloratura, Dame Shirley Bassey and Tom Jones with drawn out melodies. Even Barbra Streisand that her career as a musical singer began, could come up that made her jazz, musical and classical music equally accessible from the start with a profound vocal technique.

methodology

In the historical course of vocal pedagogy, various methods for vocal training have emerged. Each method has its own priorities and uses different ways to achieve the goals described. The applicability of different models depends on the individual disposition of the singer, his level of performance, age, attitude to singing, the training goal and other factors. There is therefore no general method for achieving the perfect voice.

The large number of methods can be roughly divided into the following groups:

One direction takes the view that all organs involved in the vocal mechanism should consciously be trained in a certain desired direction and that these new functions should be automated through constant mechanical exercise: e.g. B. certain type of breathing, jaw opening, tongue position, larynx position, adjustment of the vocal tract, expansion of resonance spaces, active use of abdominal or chest muscles for the breathing support, etc. The aim is to couple the tone formation with a certain muscularly controlled setting of the vocal tract and respiratory system.

Another direction renounces active muscular influence on the breathing and support process, active lowering of the larynx and presetting of sound spaces. It is based on a self-regulation of the body / voice instrument by stimulating natural reflexes. This category includes e.g. B. the functional voice training according to Cornelius L. Reid , other functional directions, such as the Lichtenberger Institute and the Rabine Institute, as well as the Speech Level Singing .

A third direction represents the intuitive approach, which is mainly based on the singing pedagogue's own singing experience, a good ear for sound and a good eye for a harmonious appearance. This direction rather advocates the indirect influence of the voice through musical-artistic expression, images, emotions, etc.

Smooth transitions between all methods are possible. The inclusion of new scientific knowledge about voice physiology is possible in all three groups. In addition, all directions often use or recommend additional body training such as Yoga , Taiji , Qi Gong , Feldenkrais , Alexander Technique , Terlusollogy , Kinesiology, etc., which should help to make the instrument body more permeable and free, to dissolve blockages and to improve self-awareness .

Central topics in vocal pedagogy

Anatomy and physiology

attitude

The posture of the spine influences the entire posture while standing and sitting through the muscular connections of its individual sections to the head, neck, chest and pelvis. Their natural S-shaped curvature and their stabilizing and elastic structures allow numerous movements and postures.

All organs and muscles directly and indirectly involved in the process of singing (respiratory organs, larynx, auxiliary respiratory muscles) are influenced in their function by posture and movement because of their close connection to the spine. Bad posture and malformations of the spine can therefore have a disruptive effect on breathing movements and larynx activity.

The most economical posture when singing is a natural, upright stance balanced between grounding and straightening. All variants are favorable which, with sufficient stability, result in a lively appearance of the singer and which allow the breathing and phonation muscles to play freely.

All postures that cause tension and tension on the one hand and a lack of tone or tension on the other and thus make it difficult to use the voice economically are unfavorable.

Voice breathing and support process

Voice breathing differs fundamentally from so-called silent breathing (which means both resting and performance breathing , for example in sports). The breathing movements, which are usually reflexive, can be deliberately influenced, trained and differentiated as part of singing skills within certain limits.

inhalation

You can inhale through your mouth, nose or mouth and nose at the same time. Ideally, it should be silent. The diaphragm, as the main breathing muscle, contracts and deforms the abdomen and / or the chest cavity more or less intensively , depending on the type of breathing, in cooperation with the abdominal muscles and intercostal muscles, in the form of an uplift of the ribs or a slight bulging of the abdomen.

For the majority of the authors who have dealt with the physiology of breathing and supporting processes, the so-called Kosto-Abdominal Breathing - a combination of chest and diaphragm-side breathing ( abdominal breathing ) represents the most economical form of breathing . Some authors are of the opinion, that also predominantly deep chest breathing (with diaphragm involvement) or predominant diaphragmatic flank breathing - depending on the individual requirements such as posture, movement, breathing type can be economical. Some authors or singing schools assume that effective vocal breathing occurs by itself in the course of vocal work.

For the vocal production, however, the exact form of breathing is usually not necessarily decisive, but the relationship between breath pressure and vocal fold activity. Therefore, all types of inhalation can be regarded as beneficial for vocal breathing, which allow free play of the muscles involved in the phonation process. Forms of breath that lead to tension in the neck muscles, facial muscles, chest or abdominal muscles are unfavorable (e.g. high breathing = isolated collarbone-shoulder breathing [clavicular breathing]).

Exhalation / support process

"The aim of the support process is the expedient guidance of the exhalation flow for an optimal function of the larynx, whereby the exhalation should be prolonged by maintaining the inhalation position for as long as possible".

An elastic interplay between the diaphragm and the external intercostal muscles on the one hand, or the abdominal wall and the internal intercostal muscles on the other, ensures the differentiated adaptation of the breathing pressure to the throat activity.

This finely tuned balance is known as "prop" or "supporting process". The term is derived from the Italian "appoggiare" = "to lean". The Italian Belcanto school speaks of "appoggiarsi in petto" (lean against your chest) and "appoggiarsi in testa" (lean against your head). The latter term is probably used more often in practice for the sound formation in the attachment rooms, while the first refers more to the breathing support process.

Support and support are never to be understood as pressing, prying or pressing and also not one-sided (e.g. starting from the abdominal muscles), powerful impulses or excessive use of abdominal muscles or intercostal muscles . The visible breathing movements of the chest, abdomen and flanks are only partial functions within a complex process.

Another important sub-function of the supporting process is the so-called articulation support. When the glottis is open, the air is supported against the articulation point (formation of voiceless consonants). A voice entry following the consonant can be formed more easily with the already compressed air.

If the support process is poorly coordinated, one speaks of over-support or lack of support. In both cases there is an imbalance between the tension of the larynx muscles, the diaphragm or the abdominal and intercostal muscles. In the long run, both can lead to voice disorders and voice damage.

The breathing and support process is so complex that many authors (see literature list) have dealt extensively with the different opinions and theories. There is a wide range of exercises, specific tips and recommendations for achieving the desired balance.

Phonation

During phonation, the exhaled air is held up by the vocal folds located inside the larynx . They consist of the vocal cords , the vocal muscle ( musculus vocalis ) and the overlying mucous membrane . In their original function, the vocal folds protect the airways when swallowing. They protect the windpipe ( trachea ) from dust and foreign bodies through innate reflexes. Secondly, they generate the basic sound of the voice.

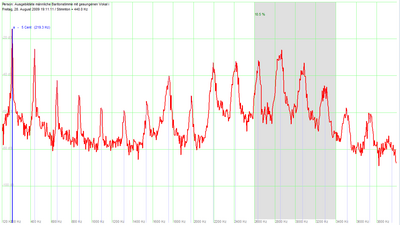

A distinction is made between two forms of movement of the vocal folds: respiratory mobility (opening and closing movements, which lead to the contact of the vocal folds and are therefore the prerequisite for vocalization) and phonatory mobility (rapid, regular oscillation of the vocal folds during phonation). This can only be viewed using stroboscopy , in which the rapid oscillation processes that are not visible to the naked eye can be photographed and played back at a slower rate. The vocal folds vibrate only in the area of the front two thirds during phonation. The back third in the area of the cartilage remains immobile.

In addition to this fundamental oscillation movement, the so-called marginal edge displacement occurs - largely independently of the muscle movement - in which the mucous membrane rolls off in an elliptical shape. Any change (inflammation, nodules, impairment from dry air, influence from medication such as cortisone, etc.) can hinder the smooth unrolling of the mucous membrane, which makes phonation more difficult and thus can lead to faster voice fatigue, changes in vocal tone and hoarseness.

The movements made visible with the stroboscope cannot fully explain the phenomenon of voice generation. The theory that is valid today assumes an interplay between the breath pressure under the glottis and the muscle forces in the larynx, which act as antagonists ( myoelastic theory ). The blowing pressure releases the closure of the glottis. The air flows out, the subglottic pressure decreases. The myoelastic forces increase, the vocal folds close. The cycle begins again. There are also aerodynamic processes. The outflowing air sucks the vocal folds towards each other and thus supports their closing movement ( Bernoulli effect ). If this process is repeated several times, regular vibrations arise in the vocal folds, which generate the vocal sound.

The vibration changes with the pitch and volume of the tone. These changes in tension are generated by fine adjustments of the vocal folds in interaction with the entire internal larynx muscles.

But the myoelastic theory is not enough to explain all the processes of phonation. Again and again there are special features that cannot be covered and are therefore still the subject of research today.

Sound shaping in the attachment spaces

The primary tone generated in this way is amplified by the resonance properties of the spaces above the vocal folds ( vocal tract , attachment tube or articulation or resonance spaces ) and formed into sounds of different types and colors. These spaces include the larynx ventricles , pocket folds , the larynx entrance, the throat , the oral cavity and the main nasal cavity . In addition, the tongue , teeth and lips, in their function as articulators, play a key role in shaping the sound.

In contrast to the main nasal cavity, the paranasal sinuses are not relevant for sound shaping. However, some singers feel vibrations in this area, which can be used helpful for the self-perception of the voice sound.

As nasality is a constructive normal connotation when speaking is called, resulting from the involvement of the nasal cavity as a resonance chamber. The soft palate and pharynx are constantly in motion while speaking and singing. With the nasals / m /, / n /, / ng / the soft palate lowers, the nasal cavity sounds in the generated consonant. The nasopharynx must be tightly closed for the plosives / p /, / t /, k / and / b /, / d /, / g / which are formed by overpressure behind the articulation point. With all other sounds the soft palate is raised or lowered differently. Coarticulation plays a crucial role here. When singing, a slightly increased nasal sound component is aimed for, which improves the projection and carrying capacity of the voice over great distances.

Pathological or negative manifestations are described with the word nasal .

Description of the acoustic laws for sound shaping:

The human voice can be measured physically in four parameters:

- Frequency (subjective pitch),

- Sound pressure (subjective volume),

- Spectrum (subjective timbre) and

- Duration (subjective tone length).

The frequency is given in oscillations per second. 1 Hertz (Hz) corresponds to 1 oscillation per second. The doubling of a number of vibrations corresponds musically to one octave . The concert pitch a (a1) was set at 440 Hz at the London Voice Tone Conference in 1938. In historical performance practice , the lower orchestral tuning usual at the time of the work in question is used, e.g. B. with 415 or 435 Hz.

The unit of sound pressure is decibel (dB) . The hearing threshold is 0 dB, the pain threshold is 140 dB. Subjectively, a doubling of the previous volume is achieved with an increase of 10 dB.

In acoustics, a tone is a simple, periodic form of vibration. Pure tones are rarely found in the physical and biological field, what is musically referred to as tone is often a composite form of vibration. When such waveforms are repeated, they are called sound .

When analyzing sound curves, it is possible to distinguish between different partials ( partials ). The first partial, which is responsible for recognizing the pitch , is called the fundamental , the following partial tones are called overtones or harmonics of the fundamental. These consecutively numbered partials form an overtone series . We subjectively perceive the partial tone spectrum as a timbre that allows us to differentiate between different vowels, the characteristic vocal sound of a person or different instruments. The differences in the timbres result from changes in the number and strength of the partials.

Notation of the first 16 tones of the partial tone series above the root C. The numbers and arrows indicate the deviation of the partial tones from the noted pitches in cents

Every vibratory system has a natural frequency. Makes a vibration at the same frequency on this system, it is to resonate the resonance excited. Air-filled cavities act as resonators. The natural frequency of a resonator depends on the volume , on the opening and, in the case of tubular structures, also on the length: the larger the volume, the smaller the opening and the longer the length, the lower the resonance frequency. A clear comparison is the one between the different instruments of a string quartet : the smaller violin with its smaller volume produces significantly higher tones than a violoncello. The smallest organ pipes let the highest, the largest organ pipes the lowest notes.

As coherent cavities, the attachment spaces can reinforce or weaken certain parts of the primary sound from the vocal folds as resonators. This creates certain intensities of the partials that shape the sound. They are called formants . A distinction is made between the vowel formants (defined as F1 and F2), which shape the sound of the vowels, and the so-called singer formants (F3 to F5), which are vowel-independent and are responsible for the carrying capacity, metal and brilliance of a voice.

The anatomical requirements of the attachment spaces, as well as their individual lining with connective tissue, muscles and mucous membrane, are fundamental for the resulting sound.

register

The term register is borrowed from organ building. There it describes a row of pipes of the same type or tone color. In relation to the human voice, he describes the phenomenon that certain frequency ranges (pitches) are generated with different vocal mechanisms.

→ Main article : Vocal register

Despite the well-describable state of research with regard to the physiological voice function, it still seems difficult to clearly assign the numerous register names in the phenomenological area to the functional registers.

Current scientific investigations endeavor to take into account both phenomenological and functional aspects to explain the complex processes. Different procedures, such as B. visual representations of the fine vibration of the vocal folds and modifications of the vocal tract as well as acoustic and electrophysiological methods are used.

For better orientation, Bernhard Richter suggests a model in which the human voice is divided into five different frequency ranges. Different register usage options can be assigned to these areas.

First range (40 Hz. To approx. 70/80 Hz.):

Straw bass, vocal fry, pulse etc.

Second range: (80 Hz. To approx. 300/350 Hz.)

Modal, M 1, chest voice, chest, heavy, speaking voice

Third range: (above 350 Hz. To 750 Hz.)

M 2

a) without changing registers: stage speaking voice, calling voice, singing voice for baritones, belting, shouting

b) with a change of register: with men in falsetto (also stage falsetto by male alto players) - middle voice of the woman

c) Stage part of the tenor above the passaggio

Fourth range: (above 750 Hz. To around 1100 Hz.)

Head voice, head, upper, light etc. Example: c3 of the sopranos is 1046 Hz.

Fifth range: (above 1100 to 4000 Hz)

Whistle voice, whistle, flageolet etc.

Vibrato

The vibrato of the singer's voice is composed of rhythmic fluctuations in pitch, volume and timbre. All three components merge into one unit in the auditory impression and are acoustically difficult to separate from each other, but the pitch fluctuations have a dominant effect.

Which physiological mechanisms lead to vibrato cannot yet be answered exactly on a scientific basis. It is very likely that both the larynx muscles and the respiratory system are involved.

According to Peter-Michael Fischer , the coordination of different vibration systems is crucial for vibrato.

- The large vibration system diaphragm-pelvic floor (breathing wave with 4–5 vibrations / second)

- The middle vibration system larynx (springy movements in its suspension system, 6–7 vibrations / second)

- The small oscillation system glottis (cartilage movement during phonation , 8–9 oscillations / second)

The individual vibration systems work together in a singer's vibrato and lead to an average vibrato frequency of 5 to 6 vibrations per second.

Faster vibrato forms with 8-10-12 pulsations per second are known as tremolo and are given colloquial adjectives such as 'trembling', 'flickering' or even, uglier, 'complaining'. Slower vibrato forms (with increased tone fluctuations at the same or too slow vibrato frequency) are referred to as 'wobble' or, in common parlance, as 'age tremolo'. The rhythmic movements of the tongue and lower jaw, which cannot be intentionally influenced, are also often noticeable here.

Conclusion

Scientific evidence can only explain part of the "singing" phenomenon. To date, research on the interactions between the individual components has not been completed. Nevertheless, the findings so far - together with my own singing experience - form an important part of vocal pedagogical work.

Voice training

Voice training is the concrete work on all parameters that are necessary for artistically usable voice production. The aim is to get to know all the components of the vocal and respiratory organs and their complex interplay, to train them and to learn how to control them in a targeted manner in order to perform musical requirements.

These include exercises for posture, breathing and support, for phonation (vocal insertion and vocal cord closure), articulation of vowels and consonants, sound shaping in the neck tube, register work, work on the vocal seat, resonance work, musical voice guidance (dynamics, legato, staccato, martellato, flexibility, Decorations, trills).

Posture, breathing and sound are closely interrelated. Body work can have a positive effect on breathing and sound, on the other hand breathing exercises can improve posture, and work on sound can have a positive effect on both breathing and posture. The procedure outlined in the following sections must therefore always be viewed in the context of these mutual interactions.

Body training

Body work is primarily about developing a conscious body awareness and thus an awareness of the interactions between the individual muscle groups.

After determining the general state of posture, which is shaped by everyday activities, habits, psychological factors, etc., the singing teacher can decide on the basis of his pedagogical concept which type of body training is necessary or helpful.

Frequent exercises in the fields are for personal training yoga , Feldenkrais , Alexander technique , Terlusollogie , spiral dynamics , etc. used. In the case of manifest bad posture, such as pelvic inclination , curvature of the spine, hunched back, etc., physiotherapy or physiotherapy may be advisable under certain circumstances .

For classical concert singing, the development of an individually balanced, lively varied stand is particularly important, as this must be maintained over a longer period of time. The position of the feet (e.g. supporting leg / free leg), the pelvic, neck and head posture must be individually tailored to the individual person (e.g. physique, proportions, breathing strategy, etc.). For choir rehearsals, which mostly take place while sitting, it is just as important to individually develop a corresponding, balanced upright sitting posture.

Musical practice and modern opera practice often require top singing performance in unusual postures and movement situations (supine, prone, rolling on the floor, seals, sliding on your knees, etc.). Singing in such conditions should be part of the professionalism of singing lessons and singing.

Body training can and should be incorporated directly into singing lessons. If more intensive training is necessary, the vocal teacher will usually recommend attending appropriate courses. A professional singing course usually includes different offers of body training.

Exercises for breathing

The opinion of the experts about whether and to what extent breathing should be the subject of the exercise is very different. The spectrum ranges from "not at all" to "extremely important",

Most authors agree that unvoiced breathing exercises make little sense because vocal breathing can only be controlled and corrected in connection with phonation. Voiceless breathing exercises can, for. B. can be used sensibly in beginner lessons to raise awareness of breathing movements.

In order to achieve the goal described in the section "Vocal Breathing and Support Process" - balance between breathing pressure and vocal fold activity - you will find a variety of exercises in all books on vocal pedagogy (see list of literature) that meet the various needs and demands. It should be noted, however, that not every exercise is necessary and useful for every student.

The type and scope of breathing training or vocal breathing training should be based on the prevailing analysis of the individual level of the vocal and breathing situation, the personality of the learner and the goal of the training.

Here are some examples of possible breathing / vocal breathing exercises:

- Exercises for self-awareness and for the awareness of natural breathing movements

- Exercises to lengthen exhalation

- Exercises to observe and stimulate reflex inhalation

- Exercises to connect consonants to the auxiliary breathing muscles

- Exercises to strengthen and flexibilize the auxiliary breathing muscles

- Exercises to stimulate breathing through specific movements

- Exercises to stretch and widen the breathing spaces

- Exercises to correct an existing imbalance - too little tension - too much tension

- ...

Exercises for phonation

Voice insert

The moment when the vocal folds go from a vibrationless state to the phonation position is called the beginning of the voice. According to the way the oscillation begins, three types can be distinguished:

- breathy voice insert

During the gradual closing process, breathing air flows past the vocal folds, which are still slightly open, and shortly before the start of the oscillation generates a more or less distinct breath sound.

- fixed voice insert (coup de glotte)

This is based on the fully closed position of the vocal folds. The air that accumulates in front of it bursts the vocal folds apart, creating the so-called glottal beat (cracking sound), which initiates the beginning of the oscillation. This use is characteristic of initial vowels in the German language.

- soft voice insert

The beginning of the voice and the beginning of the vibration of the vocal folds take place simultaneously without any noise.

In voice training, all three types of voice use are used depending on the singing style, teaching method, voice system, exercise purpose, training goal, etc. In the classic area, soft use is preferred as an ideal. Working out a soft insert is also desirable from a vocal hygiene point of view. With a good vocal technique, however, it is also possible to safely use both the breathy and the fixed use as a stylistic device.

dynamics

In order to be able to meet the musical requirements with regard to different volume levels, a classically trained singer must be able to sing a stable piano and a powerful forte , let his voice slowly swell up and down, abrupt changes in volume while maintaining the quality of the voice and to precisely set dynamic accents.

Special practice sequences are used to work on all levels of volume from piano to forte as well as on the smooth transition between different volumes ( crescendo and decrescendo , messa di voce ).

The functional voice training considered the work on the dynamics of a voice in close interaction with the coordination of the vocal register .

Legato and Staccato

When it comes to singing, legato is the seamless connection between two tones. Each tone / vowel should sound as evenly as possible over the entire duration of the tone and transition into the next vowel as seamlessly as possible. A prerequisite for good legato is, on the one hand, precise, economical consonant articulation that does not interfere with the vowel sound, and on the other hand, good register coordination that allows smooth gliding between different vowels and pitches. So working on legato is always working on all other vocal parameters.

With Staccato the short, slight bumping is meant sounds without special emphasis. The performance of a vocal hygienic staccato requires perfect coordination between larynx activity and breath pressure.

Coloratura, ornaments and trills

Coloratura , ornaments and trills require the singer to have a flexible voice. Coloratura ability is often created as a natural talent for voice. Through exercise sequences with untextured solfeggias (art of throat skill, Lütgen, or Lecons de chant, Concone) she can be awakened and trained to a certain extent in every voice.

Exercises for sound shaping

For good sound shaping, including the articulation of vowels and consonants, all the muscles involved (jaw muscles, facial muscles, lips, tongue and throat muscles) must be in a balanced state between healthy tension (tone) and looseness. Incorrect tension in the jaw area (temple muscles or other masticatory muscles) is particularly common, which can arise, for example, from misaligned teeth, teeth grinding, excessive psychological tension, etc. and can subsequently lead to tension in the neck and neck area. In order to avoid vocal problems and undesirable developments, tension must be resolved through appropriate exercises or massage.

Exercise example: To feel the temporal muscle, the fingertips can be placed on the temples. Then the teeth are clenched and loosened, clenched and loosened again - several times in a row.

Vowel treatment

In classical singing, all vowels are adapted to a desired sound ideal and tend to be aligned with one another. They also play an important role in coordinating the vocal registers. With certain pitches (especially the soprano voice) a larger opening of the jaw and throat area is necessary in order to be able to sing the required tone freely. The articulation shifts automatically from the e2 / f2 in female voices in the direction of the a sound. From the a2 onwards, no other vowels can be articulated.

Consonant Articulation

An important topic in voice training is the clear articulation of consonants without disturbing the sound production (vowel articulation). This requires precise fine-tuning of the elasticity and mobility of the tongue, lips, jaw joint, palate and throat muscles. Good consonant articulation gives the voice support and helps structure the sound. It also has a positive effect on breathing and support.

Tongue twisters in any language are good practice for quick and economical articulation.

Some examples:

- "The rickety chaplain sticks cardboard posters on the rickety chapel wall."

- "Red cabbage remains red cabbage and a wedding dress remains a wedding dress." (also possible with rolled r)

- "The airfield sparrow took its place on the airfield. The airfield sparrow sat on the airfield."

- "Chinese bowl, (3x) Czech matchbox. (3x)"

- "Steel-blue stretch denim stockings stretch dusty stretch jeans, dusty stretch jeans stretch steel-blue stretch denim stockings."

Resonances

In contrast to the sound-enhancing property of the resonating wooden walls in various musical instruments, the vibrations that many singers perceive in different bony regions on the skull, in the paranasal sinuses or in the chest do not play a role in amplifying the sound.

The walls of the vocal tract, which are lined with muscles and mucous membrane, cannot resonate by themselves, but due to the enormous variability of the positions of the larynx, epiglottis, soft palate, tongue and lips, they allow a multitude of sound and amplification possibilities, depending on the method, singing style, personal preferences etc. can be used and trained with appropriate exercises.

In the section "Sound shaping in the attachment spaces" it is described in detail according to which acoustic laws the primary tone produced in the larynx is amplified to a sonorous, far-reaching singing tone.

However, further research is required in order to fully understand the resonant properties of this system.

Voting seat

A vocal seat is the term used to describe a singer's sound or resonance strategies that contribute to the carrying capacity, penetration and brilliance of the voice. It is about the subjective feeling of a kind of sound center that the singer can feel in certain areas of his neck tube.

Seen objectively - i.e. perceived from the outside - the physiological basis of what vocal teachers call a good vocal position corresponds to an optimal setting with regard to the acoustic coupling of the glottic generator and attachment spaces.

Bernhard Richter describes phonatory and resonatory techniques to achieve a high load-bearing capacity and sufficient acoustic assertiveness, without using the term vocal seat.

Vocal pedagogy works towards this goal in different ways. Many singing teachers use terms such as front seat, mask sound, dome sound as a tool to control and monitor a desired sound quality. In addition to a combination of auditory and kinesthetic (neuromuscular) perception, Richter recommends the use of computer programs to analyze and synthesize vocal properties.

For functional methods such as Speech Level Singing or the functional voice training according to Cornelius Reid , good voice fit is a by-product of successful register coordination.

Register handling

An important goal of voice training is the tonal merging of the registers. The voice should be performed as evenly as possible and without noticeable breaks over the entire vocal range. For this work, which is called register adjustment or register adjustment, there are various, sometimes contradicting pedagogical concepts with completely different exercise contents and procedures.

- See also: Vocal Register, Section: Pedagogical Concepts for Register Compensation

In some musical styles, the natural tonal differences between the registers are used as a means of artistic expression, e.g. B. yodelling, folk, jazz and pop singing.

Development and control of vibrato

Most authors in the fields of voice research and vocal pedagogy are of the opinion that a steady vibrato occurs by itself if the play between breath pressure and vocal fold pressure is balanced and the resonance spaces are used accordingly. Certain exercises for developing vibrato are viewed by Seidner and Wendler, Franziska Martienssen-Lohmann and Heinrich von Bergen as fruitless, they plead for a gradual liberation of the voice from unnecessary tension.

Peter-Michael Fischer, on the other hand, is of the opinion that the rhythms of movement occurring in the individual forms of vibration are highly trainable. He sees the development of a so-called complex vibrato as the basis for a healthy vocal function.

According to Cornelius Reid , vibrato that is too fast (tremolo) or too slow (wobble) is a result of poorly coordinated muscle movements and can be corrected through register work. If the voice is free from unnecessary tension, in his opinion the vibrato can be controlled deliberately, i.e. strengthened or weakened. If the functional conditions are not right, vibrato cannot be induced by imitation or any other means. In this case, trying to want vibrato as part of a vocal workout is wishful thinking.

Choral voice training

The choral voice training is a special case in the vocal pedagogy. On the one hand, all the rules and goals of the individual voice training described here should ideally be observed - on the other hand, there is a completely different goal - namely the achievement of a tonal unity in the choir and thus a certain subordination of the individual voices to a common sound ideal. Choral vocal training can be incorporated into the choir work (e.g. by regular singing before the rehearsal), but it can also be given by specially committed specialists.

Vocal hygiene

Vocal hygiene is everything that contributes to the health of the singer or his voice. This includes discipline in singing and practicing, an individual warm-up program before rehearsals and performances, as well as exercises to regenerate the voice after great stress and regular vocal rest.

Since the instrument “voice” depends on the singer's healthy body, he must always pay attention to a disciplined lifestyle. Depending on his constitution, he should be aware of certain dangers to his voice and avoid them if possible or compensate for them through appropriate behavior. Here some examples:

- Smoking (also passive smoking),

- speaking loudly in crowded rooms

- frequent throat clearing

- dehydrating drinks (coffee, black tea, alcohol)

- lack of sleep

- cold and wet weather, drafts, temperature differences due to air conditioning, heating air

- Allergies (house dust, pollen, grass - avoiding contact, desensitization)

- Colds

- Medicines ( pill , sprays containing cortisone ...)

The singer can counter the natural aging of the voice with composure, good singing technique and the selection of suitable singing literature as well as the adaptation of the vocal requirements to the reduced performance. Hormonal preparations cannot stop this process.

Vocal genres and vocal subjects

| Voices for choir singers | |

|---|---|

| Female voices | Male voices |

|

Soprano (S) |

Tenor (T) |

|

Mezzo-soprano |

baritone |

|

Alt (A) |

Bass (B) |

In classical choral singing there are the vocal genres soprano , alto , tenor and bass . Classical solo singing is further differentiated; over the centuries the mezzo-soprano and baritone vocal genres have emerged.

In the last few decades a male vocal genre that uses the high register of the vocal range for sound production has established itself on opera and concert stages: the male alto, also countertenor , counter or altus. Physiologically and hormonally, countertenors have completely normal male requirements. Their singing voices in the modal part are mostly assigned to the baritone genre. Their vocal training in the high register roughly corresponds to that of women's voices. Countertenors usually sing in the mezzo soprano, but can also be trained as sopranos.

Further distinctions within the vocal genres are made via the vocal quality, which describes whether a voice has a light and playful-agile character, lyrical lines or dramatic power. In the German-speaking world, the system of vocal subjects has emerged, which enables the most precise classification of the voice to date. It is geared towards the requirements of the opera stage, which connects a certain vocal subject with a certain literature.

→ Main article : Voice subject

The determination of the pitch and the exact voice subject is often only made after several months or years in individual lessons. The decisive factor is not the attainable pitch, but the characteristic vocal sound and timbre . Decisive for a definition of the vocal genre is always the well-being of the voice in connection with the diagnostic hearing of the teacher. Medical examinations can also be consulted.

Due to changed biological conditions, a voice can change its pitch and subject over the years. This happens quite abruptly with boys 'voices who have sung soprano or alto in the boys' choir and who, after mutating, become tenors, baritones or basses.

Both in singing lessons for laypeople and in professional singing training, there are repeated misjudgments regarding the pitch and subject of the voice. Long-term singing in an unsuitable vocal subject can lead to impaired voice quality and even irreparable damage to the voice.

Work on the vocal literature

The aim of the work on vocal literature is the connection of learned vocal technical skills with the musical / artistic interpretation of vocal works.

A number of skills are required for this, either directly in singing lessons or outside e.g. B. can be acquired in minor subjects or courses or self-study. Singing students need to learn to read and understand the musical text and to work it out on their own. This requires knowledge of musical notation , ear training , harmony theory and possibly playing an accompanying instrument such as the piano. In addition, a basic knowledge of music history should be acquired for accurate stylistics. Another basis for artistic interpretation is understanding the text being sung. This requires at least a basic knowledge of common languages such as German, Italian, French, English, and in some cases also Czech, Russian and Spanish or Latin (for church music).

The art song plays an important role, especially in classical singing training . The selection of songs depends on the vocal material available, the musical / artistic talent, the vocal level of the student, but also on the skills to be learned. Literature for beginners can be found in numerous volumes of folk songs and hymn books in the anthologies "Das Lied im Studium" and other educational vocal works such as B. Heinrich von Bergens "Literature for Beginners".

Vaccai's methodically structured collection of Italian songs for high and low voices has also found widespread use . As a variant, Charles Gounod's short chants sacrés can be used, which are composed on Latin texts and can form an introduction to church music .

Personality development

The voice is part of a person's personality and can therefore not be trained in a purely technical manner independently of it. There is a close correlation between vocal development and personality development. Ideally, a vocal student has the most important personality traits for a successful professional vocal training, at least in terms of the system. These include thirst for learning, learning competence, self-discipline , patience, frustration tolerance, curiosity, enthusiasm, humor, creativity and the joy of playing. These qualities are supported, promoted and developed through good singing lessons.

During voice work, however, the student is also confronted with unconscious emotional blockages and patterns that can lead to tension and cramping on the muscular level. Discussing and resolving these patterns (in class, but also outside of it, e.g. through meditation , therapy, etc.) promotes the ability to perceive oneself and thus also awareness of one's own strengths and weaknesses and a constructive approach to negative emotions such as fears , Grief etc.

Increasing vocabulary security contributes to self-confidence - on the other hand, the progressive development of personality also has an effect on the quality of the voice and in particular on the ability for intense musical / artistic expression.

Technical aids

The first aid in vocal training was probably a mirror that enabled the student to visually control himself while singing. The mirror is used to perceive and immediately correct errors in posture, external tension in the face and neck region, incorrect jaw opening, lip tension, frown etc. It is still used in training today.

A relatively new form of direct visual control - this time with regard to acoustic parameters - is the computer technology that is increasingly being used in teaching today. There are now a number of programs for analyzing and synthesizing vocal properties that can be downloaded free of charge from the Internet. With the help of these programs, the acoustic efficiency of the singing technique can be objectified through computer feedback.

Another form of feedback is video or audio recordings of lessons or performances. Such recordings can be used to document the progress of lessons and the level of performance, or to analyze and review performances, or as a learning and practice aid (e.g. looking at / listening to a whole lesson again ...).

Further technical aids are CDs with recorded accompanying music or DVDs , which accompany the rehearsal of songs, arias, choir parts etc. in several learning steps. In many music academies there are also disklaviers that can partially replace répétiteurs .

Vocal microphones and amplifiers are used in musical and pop singing .

Artistic goals

The artistic goals depend on the type of training and the vocal and personal abilities of the student. In professional singing studies, a repertoire is built up that corresponds to the various stage roles of the personal vocal range. A number of genre-specific pieces are developed for applications to agencies, music theaters, independent ensembles, professional choirs or concert organizers.

For opera and musical singers, questions of facial expressions, gestures and physical representation on stage are also central. The basic skills for this are acquired in acting lessons and continued in connection with music. In the university's own productions, the students are introduced to working with a director .

The coordination between accompanist and singer is also important and one of the main goals in song singing .

Concert singers in the field of new music require a high level of intelligence and rapid processing of complex information, which allows them to work on works that are still unknown as quickly as possible.

For pop, rock and jazz singers, there is also band practice with the associated tasks such as the basics of microphone technology when singing and the development of a meaningful personal profile, possibly also with your own songs.

Hallmarks of good teaching

First of all, David L. Jones believes it is important to create a healthy emotional atmosphere in class. A teacher should be a leader, mentor, creativity promoter, flexible, positive partner and emotional supporter. All of these properties are important for a clear exchange of information.

In order to turn a friendly encounter into a successful learning process, there are other aspects to good teaching. According to Reinders, the following points are necessary:

A good vocal teacher

- knows how the voice works and knows how to support it with advice on posture and breathing,

- is interested in his students and not just in their voice,

- knows how to guide his students to beautiful and fascinating singing,

- does not tell scientifically untenable nonsense and not only masters his instrument, but also his subject.

The methodology and didactics of the teaching are based on the requirements of the student , the personality of the teacher and the tasks required in or outside of the classroom . These three positions can be found in the didactic triangle (see also Didactics ), which is used as a model in teacher training.

The clearest feature of a successful lesson is the tangible and audible progress in the student's vocal development. They can be documented using sound and video recordings. A comparison with other singers of the same training level can be used for better orientation. The performance of professional singers can also be compared with well-known recordings of the sung literature or through a pedagogically formulated external assessment from the outside, as it is e.g. B. happens in master classes.

Studies / training to become a singing teacher

You can study vocal pedagogy in your own courses at German and Austrian music colleges . The designation, content and curricula of these degree programs vary depending on the goal and scope of the training (e.g. Bachelor / Master / Voice and Voice Pedagogy, Bachelor / Master of Arts, Master of Music, Master of Education, etc.).

In addition to training your own voice, the course now includes the acquisition of music theory and musicological fundamentals, artistic / practical skills (piano lessons, ear training, ensemble direction, choir direction) and pedagogical skills (teaching rehearsals, internships at music schools). Many universities today also value the connection of practical / pedagogical skills to scientific examination of the anatomy and physiology of the singing voice as well as musical / vocal learning and teaching. The conclusion is a bachelor's or master's thesis.

It is advisable to find out more about the offers of the individual music universities with their different focal points before beginning a degree.

For singers with a completed artistic degree, professional singers, choir directors and interested singing teachers, the Association of German Singing Teachers offers an additional course to acquire knowledge in the areas of anatomy and physiology of the voice or didactics and methodology of singing lessons with a classical or popular focus. The "Vocal Pedagogy Certificate" or "GPZ" does not replace a study of vocal pedagogy and therefore does not qualify you to take on a teaching position or a professorship at a university.

Since the job title "singing pedagogue" is not legally protected, singers can also call themselves "singing pedagogues" who have no corresponding university degree - on the basis of their own singing experience and often in combination with private training and knowledge acquired through self-study - Give private singing lessons or master classes and workshops in different styles.

requirements

The basic prerequisite for vocal training is a healthy and resilient voice and well-functioning hearing . At some universities, a positive phoniatric report is therefore required before training begins. If voice damage is already present, it is possible to have this treated by a phoniatrist or speech therapist who is experienced with singers . This can range from absolute vocal rest to certain medicinal support to surgical intervention in severe cases ( vocal cord nodules ).

Vocal training can already begin in childhood, as has been proven by various successful children's, boys 'and girls' choirs from all over the world. Here, however, the different physiological requirements of the child's voice must be taken into account. In the mutation , careful use of the voice can still take place. After the mutation, after a stabilization phase, the voice is ready for the first training steps for adult voices.

literature

Anatomy and physiology

- Wolfram Seidner, Jürgen Wendler: The singer's voice, phoniatric fundamentals of singing. Henschel Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-89487-265-9 .

- Wolfram Seidner: The ABC of Singing . Henschel, Köthen 2010, ISBN 978-3-89487-541-1 .

- Peter-Michael Fischer : The voice of the singer. Analysis of their function and performance - history and methodology of voice training. Metzler, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-476-01604-8 .

- Bernhard Richter: The voice. Basics, artistic practice, maintaining health. Henschel Verlag, Leipzig 2013, ISBN 978-3-89487-727-9 .

- Wiltrud Föcking: Practice of Functional Voice Therapy. Springer-Verlag, 2015, ISBN 978-3-662-46605-6 , p. 175 ( limited preview in Google book search).

Didactics and methodology

- Heinrich von Bergen: Our voice - your function and care. Volume 2: Training the solo voice. Musikverlag Müller & Schade, Bern 2006, ISBN 3-9520878-3-1 , ISMN M-50023-144-8.

- Gerhard Faulstich: teach to sing - learn to sing. (Forum Music Education Vol. 24). Sixth, corr. Edition. Wißner Verlag, Augsburg 2010.

- Ernst Haefliger : The art of singing: history, technology, repertoire. 4th edition. Schott, Mainz 2000, ISBN 3-7957-8720-3 .

- Frederick Husler, Yvonne Rodd-Marling: Singing. The physical nature of the vocal organ - instructions for unlocking the singing voice. 12th edition. Schott Verlag, Mainz 2006, ISBN 3-7957-0066-3 .

- Paul Lohmann: Voice errors, voice advice. Schott, 1938–2009, ISBN 978-3-7957-0655-5 .

- Franziska Martienssen: Voice and design: the basic problems of song singing. Reprint of the Leipzig 1927 edition. Kahnt, Frankfurt am Main 1993, ISBN 3-920522-08-7 .

- Franziska Martienssen-Lohmann : Training the singing voice. Erdmann, Wiesbaden 1957

- Michael Pezenburg: Voice training: Scientific basics - Didactics - Methodology . 3rd revised and expanded edition, Wißner 2015, ISBN 978-3-95786-008-8 .

- Josef Pilaj: Learning to sing with the computer: About the application and use of new feedback options in voice training and singing. (Forum Music Education, Volume 97). Edited by Rudolf-Dieter Kraemer . Wißner, Augsburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-89639-779-9 .

- Cornelius L. Reid : Functional Voice Development. 3. Edition. Schott, Mainz 2005, ISBN 3-7957-8723-8 .

- Ank Reinders: Atlas of the Art of Singing. 2nd Edition. Bärenreiter Verlag, Kassel 1997, ISBN 3-7618-1248-5 .

- Bernhard Richter: The voice. Basics, artistic practice, maintaining health. Henschel Verlag, Leipzig 2013, ISBN 978-3-89487-727-9 .

Choral voice training

- Wilhelm Ehmann , Frauke Haasemann: Handbook of choral voice training. Bärenreiter, Kassel 1984, ISBN 3-7618-0691-4 .

- Gerd Guglhör : Voice training in the choir. Systematic voice training. Helbling, Rum / Innsbruck / Esslingen 2006, ISBN 3-85061-309-7 .

- Kurt Hofbauer: Practice of choral voice training, building blocks for music education and music maintenance. Schott Verlag, 1984, ISBN 3-7957-1033-2 .

- Siegfried Meseck: Voice training in the choir, suggestions, insights, exercises. Wißner Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-89639-478-1 .

Voice training in popular music

- Elisabeth Howard: The Power Voice . Alfred Music Publishing, 2006, ISBN 0-934419-19-1 .

Web links

Addresses

Educational institutions

- Music schools in the VdM in Germany

- Free music schools in Germany

- Music colleges in Germany

- Music academies, church music colleges

Historical singing schools

- Opinioni de 'cantori antichi e moderni : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project . Italian singing school by Pier Francesco Tosi , translated into German by Johann Friedrich Agricola (1757)

- Sheet music and audio files from vocal pedagogy in the International Music Score Library Project by Manuel García Jr. (en)

- My singing skills : sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project singing school by Lilli Lehmann

Phoniatrics

- cvnrw.de (PDF; 1.5 MB) Pharmacological effects of drugs on the voice function, Martina Gabriele Müller-Greis

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ernst Haefliger: The art of singing. P. 18.

- ↑ Ernst Haefliger: The art of singing. P. 26.

- ↑ Ernst Haefliger: The art of singing. P. 28.

- ↑ cit. after G. Panconcelli-Calzia in: Ernst Haefliger: The Art of Singing. P. 30.

- ↑ cit. in Ernst Haefliger: The Art of Singing. P. 33.

- ↑ see Ernst Haefliger: The Art of Singing. P. 46.

- ↑ http://www.noelle-turner.de

- ↑ cf. Seidner / Wender, pp. 52 and 58

- ↑ cf. Michael Pezenburg: Voice training, scientific principles - didactics - methodology. ISBN 978-3-89639-539-9 .

- ↑ cf. Seidner / Wendler: Die Sängerstimme , 2004, p. 54 and p. 58–61.

- ↑ Leslie Kaminoff: Yoga Anatomy. Riva Verlag, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-936994-79-7 , pp. 18, 19, 20.

- ↑ Brigitta Seidler / Winkler: There are two graces in breathing

- ↑ z. B. Cornelius L. Reid: Functional Voice Development

- ↑ cf. Seidner / Wendler: The singer's voice. 2004, p. 63.

- ↑ cf. Michael Pezenburg: Voice training, scientific principles - didactics - methodology. P. 34.

- ↑ Seidner / Wendler: The singer's voice. P. 63.

- ↑ cf. Michael Pezenburg: Voice training, scientific principles - didactics - methodology. P. 34 and 35

- ↑ cf. Seidner / Wendler: The singer's voice. 2004, p. 64.

- ↑ cf. Seidner / Wendler: The singer's voice. P. 65.

- ↑ cf. Michael Pezenburg: Voice training, scientific principles - didactics - methodology. P. 38.

- ↑ cf. Matthias Echternach, Bernhard Richter In: Bernhard Richter: The voice. Henschel 2013, p. 143.

- ↑ cf. Matthias Echternach, Bernhard Richter In: Bernhard Richter: The voice. Henschel 2013, pp. 137/138.

- ↑ cf. Sundberg 2013 in Bernhard Richter: The Voice. Basics, artistic practice, maintaining health. Henschel Verlag, Leipzig 2013.

- ↑ cf. Peter-Michael Fischer: The voice of the singer. Analysis of their function and performance - history and methodology of voice training. Metzler, Stuttgart 1998, pp. 141-166.

- ↑ cf. Heinrich van Bergen, The training of the solo voice. P. 4, 5.

- ↑ cf. Seidner / Wendler 2004, p. 58.

- ↑ cf. Pezenburg, Wißner 2007, p. 45.

- ↑ Cornelius Berger: Breathing while singing, practice breathing or not? Term paper at the University of Siegen, 2010.

- ↑ cf. Pezenburg, Wißner 2007, pp. 45/46/47

- ↑ cf. Pezenburg, Wißner 2007, p. 49.

- ↑ http://www.bengtson-opitz.de

- ↑ sprueche.woxikon.de

- ↑ cf. Bernhard Richter: The voice. P. 61.

- ↑ cf. Michael Pezenburg: Voice training: Scientific basics - Didactics - Methodology. Wißner 2007, p. 94.

- ↑ cf. Seidner, Wendler, 1997, p. 119 near Pezenburg, 2007, p. 94.

- ↑ cf. Bernhard Richter: The voice. Basics, artistic practice, maintaining health. Henschel Verlag, Leipzig 2013, p. 88.

- ↑ cf. Bernhard Richter: The voice. Basics, artistic practice, maintaining health. Henschel Verlag, Leipzig 2013, p. 152.

- ↑ cf. Bernhard Richter: The voice. Basics, artistic practice, maintaining health. Henschel Verlag, Leipzig 2013, p. 90.

- ↑ Heinrich von Bergen, Training the Solo Voice, pp. 108/109.

- ↑ see Peter-Michael Fischer: The voice of the singer. Analysis of their function and performance - history and methodology of voice training. Metzler, Stuttgart 1998, pp. 141-166 and 276.

- ↑ cf. Cornelius L. Reid: Functional Voice Development. 3. Edition. Schott, Mainz 2005, pp. 57/58.

- ↑ cf. Bernhard Richter: The voice. Basics, artistic practice, maintaining health. Henschel Verlag, Leipzig 2013, pp. 107, 108.

- ^ Paul Lohmann: The song in the classroom. Schott Publishing House. Middle / low voice: ISMN 979-0-001-04027-3; high voice: ISMN 979-0-001-04026-6

- ↑ Heinrich von Bergen: Literature for the beginning lesson. Supplement to "Our voice - its function and care", Schott Verlag

- ↑ cf. Bernhard Richter: The voice. Basics, artistic practice, maintaining health. Henschel Verlag, Leipzig 2013, pp. 90–58.

- ↑ Josef Pilaj: Learning to sing with the computer: About the application and use of new feedback options in voice training and singing. (Forum Music Education, Volume 97). Wißner, 2011, ISBN 978-3-89639-779-9 .

- ↑ gesanglehrer.de

- ↑ Ank Reinders: Atlas of Singing Art. P. 161.