History of New Zealand

The history of New Zealand is young compared to that of other countries in the world. From a geological point of view, the islands are among the youngest on earth, and from a cultural and historical point of view, New Zealand is the last country to be inhabited and designed by humans. From a European perspective, New Zealand is on the other side of the world. This explains why the islands in the southern Pacific , which today make up the state of New Zealand, received attention very late in the middle of the 17th century.

Prehistoric time

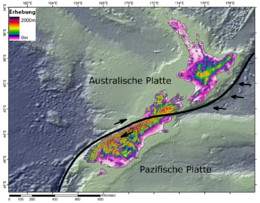

About 130 million years ago, a land mass split off from the supercontinent Gondwana and began to drift apart 45 million years later, divided into the land blocks of Antarctica , Australia and New Zealand. After another 15 million years, when New Zealand's land mass was much larger than it is today, a slow process of erosion began, which after 35 million years had brought 60% of today's land area below sea level. New Zealand would have almost disappeared had it not been for a deformation process in the form of upheavals caused by the clash of the Pacific plate and the Australian that began about 26 million years ago to re-form New Zealand, although this process is far from complete. Most of the mountain formations had formed as a result of tectonic shifts 5 million years ago, while other mountains and landscapes were formed as a result of volcanic activity. New Zealand is significantly shaped by these geological processes of the earth and is still one of the earthquake-richest countries on earth.

Due to the separation and isolation of New Zealand from other land masses, the flora and fauna of the country developed in a unique way. Over 90% of the country was covered with jungle. There were no mammals or snakes, and the few predators evolved exclusively in the world of birds. It was this that produced flightless birds like the kiwi , ratites over two meters tall like the moas and parrots like the kea , which is native to the alpine mountainous landscapes of the South Island and is still comfortable in the cold region in the snow even in winter feels. The ecosystem of New Zealand had established itself perfectly over many millions of years, despite temporary destruction by volcanic activities, and produced many endemic species of plants and animals. Their existence did not seem to be endangered for thousands of years until finally humans came.

Discovery and settlement

Colonization by Polynesians

The first human settlement of New Zealand came from the Polynesian Islands . There is little reliable information about the exact time when the immigrants first set foot on New Zealand soil. However, it is undisputed that the conquest of the Pacific region started from Asia . As the archaeologist Professor Peter Bellwood described in 2008, one can assume that in the 4th or late 5th millennium BC the first settlements of the Chinese provinces of Zhejiang and Fujian based on Taiwan have been made and its southern islands, followed by the Philippines to 2000 BC Chr . Around 1500 BC The early conquerors moved on across the Moluccas and East Timor and settled between 1500 and 1350 BC. In the islands of Melanesia known for the Lapita culture , including the Bismarck Archipelago . Around 1050 BC Then the Solomon Islands and between 1000 and 800 BC. The western part of Polynesia was conquered.

From there the seafarers moved in the direction of Hawaii around 400 AD , at around the same time to the more eastern Polynesian Islands up to Easter Island , and after 1200 AD they finally reached New Zealand, which is far more south. Evidence of deforestation and examinations of found bones of the Pacific rat (Polynesian name: Kiore ) imported by immigrants, together with seeds nibbled on it using the radiocarbon method , put the arrival of the Polynesians in New Zealand at around 1280 AD.

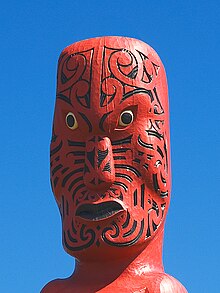

The descendants of these first immigrants founded the Māori culture , although the exact origin of their ancestors cannot be determined with certainty. If science currently assumes that the ancestors of the Māori came from the Society Islands and Cook Islands , which are close to New Zealand , the myths of the Māori partly justify their origin from the mythical Hawaiki , the place to which their souls would also return after death. Her ancestor Kupe is said to have discovered the uninhabited land from there around 925 AD, and his wife traveling with him, upon seeing a large white cloud, called this land Aotearoa , The land of the long white cloud . In the 13th century, based on Kupe s information, the "large fleet" with seven canoes is said to have set out for New Zealand. So much for the Māori perspective .

At what point in time one can speak of a Māori culture is unclear. It can be assumed, however, that 500 years without further cultural influences from outside and the process of adaptation to the conditions in New Zealand have shaped the immigrants in a special way. The Air New Zealand was colder and rougher than in its subtropical home. The first experiences with snow must have been correspondingly impressive. The soil in their new home was also not as fertile as where they came from, and u. a. Kūmara , yams and taro could be grown. Accordingly, the Māori initially developed into hunters, because the meat of a moa weighing up to 240 kg , as an example, was sufficient enough to feed on for a while. But the extinction of the moas in just a few decades and the increase in their population forced the Māori to change their diet. In addition to traditional fish consumption, they also began to farm.

The Māori organized themselves into tribes ( Iwi ) and their subdivisions ( Hapū ) and lived in fortified villages called Pā . Starting from the north, they populated the North Island , the South Island , Stewart Island and the Chatham Islands . Their impact on New Zealand's wildlife through hunting and imported domestic animals has been dramatic and resulted in the extinction of numerous animal species, the best known of which are the moas and the great eagle .

Armed conflicts were part of life among the Māori , mostly about land and what people were killed for. The defeated opponent was often left with only death, either immediately killed in combat or later in captivity and then eaten, because cannibalism was also a part of Māori culture to which women and children also fell victim. Cannibalism was also a regular practice in wars where human flesh was an important part of the warriors' diet. The subject of cannibalism has long been ignored in New Zealand and is absent from most of the country's history books, as New Zealand historian Paul Moon noted in August 2008. But cannibalism was practiced among the Māori until the mid-19th century .

Discovery by Europeans

Abel Tasman

It should be left to the Dutch navigator Abel Janszoon Tasman as the first European to discover New Zealand, which is more than 17,000 nautical miles from his home country. Under the pay of the Dutch East India Company and the order of the governor of the Dutch East Indies , Anton van Diemen , the southern continent Terra Australis Incognita to find himself made Abel Tasman on August 1, 1642 the two ships Heemskerck and Zeehaen of the Indonesian Trade center from Batavia on the way south. A good four months later, on December 13th, they reached the west coast of the South Island of New Zealand at what is now Westport . But heavy seas and adverse winds made it possible to go ashore for the first time on December 18 in what is now Golden Bay . Presumably based on a misunderstanding, one day later the first contact between Europeans and Māori ended fatally for four seafarers in the fleet. The Ngati Tumata tribe had attacked a dinghy of the expedition ships, whereupon Tasman ordered an immediate retreat, defending against cannon fire. After this experience, he named the bay Killer Bay and sailed further north along the west coast of the North Island. He himself had never set foot on New Zealand soil.

Believing that he had found part of the land east of Cape Horn , discovered by Jacob Le Maire in 1616 , he named the land Staten Landt (after the Dutch States General ) . However, when the navigator Hendrik Brouwer recognized in 1663 that Le Maires Staten Landt was a small island and was not connected to Tasman's Staten Landt , the Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu decided to name the land discovered by Tasman as New Zeeland ( Latin : Nova Zeelandia ). Nieuw Zeeland was not forgotten, but it would be 127 years before Europeans paid attention to the country again.

James Cook

In May 1768 the British navigator James Cook was commissioned by the Royal Society to lead an expedition to observe the Venus Passage on Tahiti . Furthermore, he should investigate whether there is more land south of Tahiti. Provided with information about the Pacific voyages of his predecessors Francis Drake , John Byron and Samuel Wallis , Cook left Plymouth on August 26, 1768 with the Endeavor . After Cook's astronomer Charles Green had successfully carried out the observations on June 3, 1769, he sailed south in search of more land.

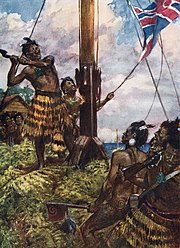

It was the cabin boy Nicholas Young who reported "land in sight" on the afternoon of October 7, 1769 at around 2:00 p.m. New Zealand was rediscovered. The bay, in which Cook went ashore two days later, he described with disappointment as Poverty Bay , because there was no way to take in water and provisions. Cook sailed further north on the east coast of the North Island, mapping the land and giving names to striking bays, capes and mountains that could be seen from the sea. While going ashore on November 15, 1769 in Mercury Bay on the North Island, he formally hoisted the Union Jack on behalf of the reigning British King George III . He repeated this land appropriation in January 1770 in Queen Charlotte Sound on the South Island.

When Cook left New Zealand for Australia on April 1, 1770 , he had circled both main islands on his almost 6-month journey and documented them so well that the first map of the country came very close to the real conditions. Cook only made two major mistakes. On the one hand, he made the Banks Peninsula an island, and on the other, Stewart Island a peninsula. On numerous trips ashore, the scientific companions Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander , both botanists , had the opportunity to collect, describe and catalog plants. The natural draftsmen Sydney C. Parkinson and Herman Spöring created the illustrations. Cook knew how to communicate with the Māori with the help of an accompanying Tahitian , and thus to learn more about their life and culture. Even if there were isolated conflicts, his experiences with the Māori were mostly positive.

Cook's notes made it clear that he considered New Zealand an excellent settlement area. Rich in fertile land, on which European plant cultures would thrive, he painted an extremely positive picture in which he saw no danger from the Māori either. Cook led two other expeditions, which he u. a. also come back to New Zealand. On the second trip Tobias Furneaux accompanied him with the Adventure .

Jean François Marie de Surville

Britain wasn't the only country interested in the Pacific. In 1766 at the latest, France documented its interest in the unexplored world with the circumnavigation of Louis Antoine de Bougainville .

Inspired by a rumor about a rich foreign land which the English are said to have discovered, the French trader and navigator Jean François Marie de Surville set out with his ship Saint Jean Baptiste in March 1769 . Impaired by scurvy and other diseases, Surville , remembering Tasman's descriptions of New Zealand , tried to find this coast for fresh water and provisions. On December 12, 1769 he reached the North Island near Hokianga Harbor and sailed further north in search of a suitable anchorage. Curiously, on December 13th, Cook and Surville passed the northern tip of New Zealand during a storm at a short distance in opposite directions without being able to notice each other.

Surville finally anchored a few days later in a bay that Cook had named Doubtless Bay , which Surville has now called La Baie de Lauriston . After Māori came into possession of a dinghy that was lost in a storm, Surville's people kidnapped the chief of the Māori tribe and left New Zealand after fighting . Ranginui died of scurvy on March 24, 1770. This incident retrospectively damaged Surville's reputation in New Zealand. A little later he also died off the coast of Peru .

First settlement by Europeans

Traders, whale and seal hunters

Inspired by Cook's positive reports and driven by the hope of doing good business, interest in New Zealand rose rapidly from the beginning of 1790. The governor of New South Wales , Philip Gidley King , even went so far as to bring the coveted New Zealand flax to the penal colony on Norfolk Island and have it processed there, and in 1793 to kidnap two Māori who were supposed to teach the flax processing technique to the Europeans . For the Māori , flax was an all-purpose plant. You use it u. a. for the production of ropes, mats, baskets and clothes. The nectar of the plant was suitable for sweetening food and medicine could also be obtained from the juice of the leaves. All this attracted traders and led to the fact that on the one hand the flax trade became one of the most important economic sectors in the country in the first decades and on the other hand the contacts between Māori and Europeans deepened. In addition to flax, the trade in tropical New Zealand timber also got underway, and its customers were also in New South Wales .

The first whaling ship to officially call at Sydney Harbor from New Zealand was the Greenwich in 1803 . Your captain reported on other ships that were already operating in New Zealand waters. The whale and seal fishing developed into the second most important branch of the economy in the early years. Numerous whale and seal hunters came from America and Australia and set up their whaling stations around New Zealand's coasts. They proceeded with unbelievable brutality and slaughtered everything that came before the shotgun or harpoon . Her life itself was also marked by extreme brutality. John Boultbee , one of the few educated sealers, recorded his experiences, which allowed appropriate conclusions.

The Bay of Islands emerged as the focus of the early settlements . Here, in the Māori settlement of Kororāreka , today's Russell , New Zealand's first trading center was built. But the dealers and whalers were soon joined by adventurers, smugglers and liquor dealers. Even escaped convicts from the British colony of Australia and deserters from ships tried their luck in the emerging town. Immediately a lawless area was created, marked by violence, which Kororāreka became known as the hell-hole of the Pacific ( Hellhole of the Pacific ). When faced with such news, the British government initially developed no further interest in getting involved in New Zealand. Those who came did so on their own account and tried their luck. Little by little, settlers came, mostly from Great Britain, and slowly migrated south to settle in the coastal regions. But the big boom still failed to materialize.

Influence on the Māori

The arrival of the Pākehā , as the Europeans were called by the Māori , had a dramatic impact on their tribes ( Iwi ). Not only that the Europeans were superior to their culture in technology, knowledge and weaponry. With them came diseases that the Māori had not known before. Influenza , measles , smallpox , tuberculosis , typhoid and other epidemics spread. In addition, in the trade in land, fruits and other agricultural products, individual Māori tribes received weapons from the Europeans in return. The muskets were in great demand, as they promised considerable advantages in the fight against competing tribes. An estimated 10,000 Māori died in the so-called Musket Wars , in which tribes of the North Island fought their disputes . Overall, it is estimated that of the 100,000 to 200,000 Māori living in New Zealand around 1800, only 70,000 survived by 1840.

Missionaries' race

Organized by Samuel Marsden , the first British missionaries Thomas Kendall and William Hall reached New Zealand on June 10, 1814 . They and those who followed them set up mission schools and tried to spread the Christian faith among the Māori with their sense of mission . Strict, paternalistic and shaped by puritanical tradition, they found it difficult to understand the culture of the Māori and to convince them. This changed in 1823 with the missionary Henry Williams . Thinking practically, he won over the influential chief Hongi Hika by having a ship built to encourage trade between the tribes. With Williams , the Anglican Church Mission Society (CMS), which appeared as the first mission church in New Zealand, expanded rapidly. It was followed in 1823 by the Methodists and in 1838 by the Catholic Church in a kind of competition among themselves. In 1840 the Anglicans counted around 30,000 Māori converted , the Methodists around 1,500 and around 1,000 turned to the Catholic Church.

Emergence of the state

First declaration of independence

In order to be able to protect British settlers in New Zealand, the British government placed New Zealand under the supervision of the Supreme Court of the New South Wales Colony . But at a distance of more than 2000 km over water, this had practically no effect. Unrest and conflict with the Māori and among the Māori tribes continued. In addition, with the presence of a French warship in the port of the Bay of Islands in 1831, the British became concerned that France might preempt the British by annexing New Zealand. In response to this, the Colonial Office (British Colonial Office ) sent James Busby to the islands as British resident in 1833 and, with him as the official representative, showed for the first time a serious interest in the country. The idea of giving New Zealand its own legal authority should be implemented by Busby. Equipped with no means of power or direct competence, he should ensure order and security. Nevertheless, he managed to be accepted as a mediator by the Māori heads.

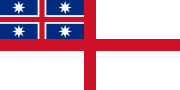

On March 20, 1834 gathered at his invitation, the Māori - chiefs of the northern region in order of three he designed flags for the union of all a Māori should be strains to select. On 28 October 1835 he persuaded 34 Maori -Anführer as United Tribes of New Zealand (Confederation of United Tribes) the Declaration of Independence of New Zealand to sign. Although the tribal leaders had no say in the preparation of the document, other chiefs signed in the following years, so that in 1839 a total of 52 Māori had signed. Not much changed for the Māori , but in terms of foreign policy this meant to France that New Zealand could not be taken by surprise and that Great Britain might be available as a protective power. But this still required a corresponding agreement.

Colonization by Great Britain

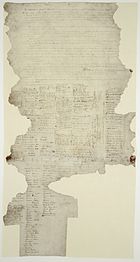

Treaty of Waitangi

As early as 1837, Busby had sent a warning to London that the ongoing armed conflicts among the Māori could endanger the security of the British settlers. Captain William Hobson , who was active in the British colonies of Australia at the time, came a few months later to examine the situation. In 1838 he sailed with his report to England and submitted the proposal to the Colonial Office , similar to the one in the East Indies , to establish trading branches in New Zealand and to secure the land for England through a corresponding treaty.

The Colonial Office accepted and authorized Hobson as Vice-Governor of New Zealand and subordinate to the Governor of New South Wales , George Gipps , to negotiate accordingly with the Māori . Hobson reached Bay of Islands on 29 January 1840 and invited all northern Māori - Chiefs to a meeting on 5 February in Busby's home after Waitangi one. A day later it was agreed and 45 of the present Māori - Chiefs signed a contract as the Treaty of Waitangi was an important place in New Zealand's history and was the birth certificate of modern New Zealand. In commemoration of this day, February 6th became a national holiday in 1974 and has been celebrated as Waitangi Day ever since .

The treaty gave the Māori protection and guarantees that they could keep their possessions. In return, they gave up their sovereignty and accepted the British crown as their new authority. This completed the annexation of New Zealand and declared the country a British colony . But the different interpretations of the treaty soon led to new tensions between Pākehā and Māori , which finally found expression in the so-called New Zealand Wars from 1843 to 1872.

Hobson , of the reputation of Kororareka not particularly impressed, bought a few kilometers south in Okiato country named the place in honor of the late British Prime Minister John Russell in Russell around, and declared the place as the capital of the country. A year later, in 1841, he made Auckland the capital, but in 1865 the capital was moved to Wellington by order of Governor George Edward Gray .

The role of the New Zealand Company

Since the founding of the first New Zealand Company in 1825, New Zealand has been regarded by British investors as an excellent object of speculation. Wealthy, influential people saw the colonization of New Zealand by British emigrants on the one hand as a solution to Great Britain's social problems, but on the other hand they also promised high speculative profits through the sale of New Zealand land.

But it wasn't until the second New Zealand Company was founded on August 29, 1838 that the colonization project really got going. Despite the resistance in the British government, the promoter for the colonization of New Zealand, Edward Gibbon Wakefield prevailed and on May 12, 1839 sent his brother William Wakefield to New Zealand to prepare the settlement of British immigrants. In a dispute with the government and with promises that could not be kept to resettlers, the first settlers reached Port Nicholson on January 22nd, 1840 , the natural harbor where Wellington , today's capital of New Zealand, was later founded. The New Zealand Company continued to pursue their own interests, even after the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and Vice Governor Hobson's proclamation of sovereignty over the whole country on 21 May 1840 for about the same time she made with the settlers in Port Nicholson , a own government.

And although the New Zealand Company was a bitter opponent of the Treaty of Waitangi , the British government later accepted its role as a promoter of the colonization of New Zealand and even saved the company from financial bankruptcy in mid-1845. Despite its dubious settlement practices, the Company brought over 9,000 settlers to New Zealand in the first six years in connection with the founding of Wellington (1840), Wanganui (1840), New Plymouth (1841) and Nelson (1842). In 1858 the New Zealand Company was dissolved after further financial difficulties.

New Zealand Wars

In contrast to the Musket Wars of the 1820s and 1830s, in which the Māori tribes fought one another, the clashes known as the New Zealand Wars were conflicts that were largely fought between Māori and Pākehā . Mostly it was about land that settlers wanted to appropriate or about broken promises. Unjust treatment of the Māori also partly led to an anti- Pākehā movement, such as that of the religiously determined Pai Mārir movement, which turned against the influence of the Europeans and their Christian faith and which escalated into struggles in 1864/65. The wars are generally set in a period from 1845 to 1872, but the conflict of 1843, known as the Wairau Turmoil , in which the attempted conquest of Arthur Wakefield of the New Zealand Company took place, can be considered the first armed conflict.

Economic development and gold rush

At the beginning of the 20th century, the dairy farming industry grew in response to increasing demand in Europe. This changed the economic system. Due to the increasing production, new production techniques were needed. The use of factors also became more efficient. Most of the capital to make this change came from abroad.

Before the turn of the century, the country's economic development was essentially determined by two factors, the gold rush in Otago and the development plan of Julius Vogel , who later became Prime Minister . Gold was found on the Coromandel Peninsula as early as 1842 , but the gold discovery by gold prospector Thomas Gabriel Read in May 1861 should overshadow everything that had existed before. Within a few weeks and months, more than 10,000 prospectors came to Otago , and Dunedin, as the capital of the region, became the richest city and the economic and cultural center of the country for a few decades.

In 1870 Julius Vogel, who was still finance minister at the time, pushed through an ambitious state development plan. His plan was to bring specialists and workers to New Zealand and with them to expand and improve the country's infrastructure . In just under a decade, more than 200,000 immigrants came into the country in this way, and built roads, railways and telegraph networks. But after the decade of recovery came the difficult economic times known as " The long Depression " (1885–1900) in New Zealand. Immigration slackened and in 1888, with around 100,000 more emigrants than immigrants, even had a brief reverse trend.

Pioneer in independence and the right to vote

New Zealand developed a little more idiosyncratic and independent than other British colonies. So who got Māori by the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 guaranteed the right to self-government. Although this right was never applied, it existed until the Constitution Act was amended in 1986. New Zealand was also the first country in the world to grant its natives the right to vote and, with the Māori Representation Act on October 10, 1867, four seats in parliament pledged, three for the North Island and one for the South Island. Settlers without their own house, on the other hand, had to wait 12 years for their right to vote.

Also in relation to the women's suffrage New Zealand in the vanguard: After a six-year campaign led by the social reformer and suffragette Kate Sheppard 's efforts in 1893 were successful. On September 8, 1893, the law giving New Zealanders of British citizenship 21 and older women the right to vote was passed with a majority of two votes. Maori women were included. On September 19th, the Governor Lord Glasgow signed it , which brought the law into effect. However, some groups of women were still excluded; as in some other states, this included prison inmates and women in psychiatric hospitals. The passive right to vote for women in the House of Commons elections was not achieved until October 29, 1919 with the Women's Parliamentary Rights Act . It was not until 1941 that women gained the right to stand for election to the House of Lords .

First World War

Immigration to New Zealand came to a complete standstill during the First World War 1914–1918, and political tensions did not stop at distant New Zealand. Germans were hated and struggled across the country, and in some parts of the country they went so far as to obliterate all German names of streets, places, and the like. The 1919 Undesirable Immigrants Exclusion Act gave the Attorney General the power to turn away undesirable foreigners. Germans and socialists were treated as such , but aversion to people of Asian origin also increased. New Zealand, which saw the support of Great Britain in the First World War as a national duty, experienced a national tragedy together with the Australians in the battle for Gallipoli against Turkish defenders. 2,721 New Zealand soldiers died and 4,752 were wounded. Even today, ANZAC Day is celebrated every year on April 25th in memory of the fallen and, together with Waitangi Day, is one of the most important holidays in the country. New Zealand, which at the time of the First World War had a population of just over one million, took part in the war with 103,000 nationals (including nurses and auxiliary staff). 42% of the male population served in the war. 16,697 New Zealanders died and 41,317 were wounded. It is estimated that several thousand men died as a result of injuries in the five years after the end of the war. 507 died while training between 1914 and 1918. After Serbia, New Zealand had the highest casualty rate during the war.

New Zealand's road to independence

New Zealand has been a British colony since the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840. After all previously independent colonies on the Australian continent had merged to form the Commonwealth of Australia on January 1, 1901 , a debate broke out in New Zealand about becoming part of this federation. Following a recommendation from the Royal Commission , the New Zealand Parliament, under the leadership of Prime Minister Richard John Seddon , declared on May 30, 1901 that it did not want to join the Federation.

With effect from July 12, 1907, the New Zealand parliament accepted Dominion status for the country six years later , despite considerable concerns among politicians and the public as to whether a country as small as New Zealand with the intended independence and autonomy would even survive could. With this recognition, New Zealand was also a member of the British Commonwealth of Nations .

With the entry into force of the Statute of Westminster, 1931 on December 11, 1931, the Dominions of Great Britain were given the opportunity to formally recognized independence under international law . However, New Zealand only used this with the passage of the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1947 , which became legally effective on November 25, 1947.

Second World War

Although half a globe away, New Zealand, along with Great Britain, was one of the first two countries to declare war on their own on September 3, 1939, after German troops marched into Poland (see attack on Poland ). As in the First World War, it was clear to New Zealanders to stand on the side of Great Britain. Of the approximately 1.6 million inhabitants of New Zealand at that time, around 140,000 of them were involved in fighting in Egypt , Italy , Greece , Japan and the Pacific . After the end of the World War, New Zealand counted 11,928 dead and an unknown number of wounded.

Sovereign state under the British Crown

New Zealand Constitution Act

Until the 1986 Constitution Act came into effect in 1986, the UK was able to legislate for New Zealand upon request and in coordination with the New Zealand Parliament. Starting with the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 , with which the British government first installed a representative political system under the leadership of Governor George Edward Gray in New Zealand, to the Constitution Act of 1986, with which New Zealand first named laws that summarized the character a constitution, a very cautious path to independence was taken. Andrew Sharp , Professor of Politics at the University of Auckland , attested that New Zealanders were not very interested in their own constitution. Public indifference and sluggish reactions from politicians are the cause. In 1986, the Official Committee on Constitutional Reform ( Official Committee for the constitutional reform ) the bill created, it is his statement to "poor" eight inputs have given.

Although New Zealand does not have a constitution written in a single document, at least the Constitution Act provides information about which other laws and statutes have constitutional status.

Parliamentary system

When the parliamentary system of New Zealand was installed in 1852, Westminster democracy based on the British model was adopted. The Legislative Council established in 1857 corresponded to the British House of Lords , also known as the Upper House , and the House of Representatives to that of the House of Commons , also known as the Lower House .

The Legislative Council was originally intended as a control body and was supposed to ensure that legislative initiatives by the House of Representatives did not get out of hand. But after fierce disputes and controversies in the 1860s and 1870s, the council only assumed an advisory role. In 1951 the Legislative Council was abolished and the functioning of the parliament reformed. Frustrated by the rigid two-party system, majority voting was finally abolished in 1996 and changed to the Mixed Member Proportional System , a personalized proportional representation based on the German model.

Waitangi Day and Waitangi Tribunal

In 1932, the then Governor General of New Zealand , Charles Bathurst, 1st Baron Bledisloe, presented the Treaty House , built in 1833 by James Busby in Waitangi as a home for his family, as a gift to the nation in the hope that the house would become a memorial to the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi on February 6, 1840. Two years later, in 1934, the day of remembrance was celebrated in public for the first time. Over 10,000 Māori are said to have attended the celebrations. In 1973, the Labor Party, headed by Prime Minister Norman Kirk , made Waitangi Day a national holiday. In 1974 the holiday was celebrated nationwide for the first time and since then has been a constant reminder, on the one hand of the historic signing of the treaty and thus the founding of the nation, and on the other hand of the promises that were not kept to the former native inhabitants of the islands, the Māori .

In order to be able to keep these promises and to check where and where the injustice had been done to the Māori , the Waitangi Tribunal was set up in 1975 by Prime Minister Bill Rowling with the Treaty of Waitangi Act . In August 2002, the tribunal registered the 1000th submission of a legal claim since its existence, stating that the controversy was not without tension, is understandable. In the vast majority of cases, it was about the return of unlawfully appropriated land or corresponding compensation. The tribunal went too far for some and not fast enough for others, the Māori .

Maori protest movements

It was precisely the emerging protest movement among the Māori that, with pressure on the Labor government (1972–1975) and the subsequent government of the National Party (1975–1984), set the so-called Waitangi Process in motion. Out of anger at the ongoing land grabbing, caused by the laws of the National Party of the 1960s, resistance formed, which with the Māori land march of 1975 also attracted attention beyond the borders of New Zealand. The march was the prelude to the Māori Land Rights Movement , which dragged on until around 1984 and was then absorbed by new social movements in search of the cultural identity of the Māori people.

Effects of Great Britain joining the EC

When Great Britain joined the European Community (EC) (now EU ) in 1973 under Edward Heath , New Zealand fell into a severe economic crisis. Until then, all economic contacts between New Zealand and the mother country were possible without any trade restrictions, but now customs duties had to be paid for imports into Great Britain. As a result of these difficulties and increases in costs, a competitive advantage was lost and thus by far the largest market for the country. Then there was the oil crisis, triggered in the same year, which caused fuel prices to explode and thus put New Zealand's exports on the back burner. This resulted in unemployment and a sharp rise in social spending. The ruling Labor Party was voted out of office in 1975, but the National Party also lost control of the state budget . In 1984 the Labor Party regained power. It was trusted now to save the economy and the state finances.

National debt and wave of state privatization

In 1984 the state treasury was over-indebted, the interest burden extremely high and the economy on the ground. Under the leadership of Prime Minister David Lange and his Finance Minister Roger Douglas , serious cuts and changes to reorganize the state followed. With liberal market approaches they tried to get the financial problems under control. They released the exchange rate of the dollar , introduced the Goods and Services Tax (GST) (comparable to VAT), cut subsidies for agriculture, reduced taxes on businesses and imports, reduced the incomes of the country's citizens, and managed a wave of privatization on state property and state enterprises. Among other things, the Postal Services Act 1987 split the state post into Post Office Bank , New Zealand Post and Telecom Corporation of New Zealand , in 1989 the airline Air New Zealand was privatized, and from 1990 the railway system was sold to investors from Australia and the United States . Two years after the Labor Party came into power , Lange and Douglas also faced severe criticism from within their own party. Douglas, whose signature was liberalization policy, was dubbed Rogernomics for his policy , based on Reaganomics , the market-liberal policy under the former President of the USA, Ronald Reagan .

Anti-nuclear policy

New Zealand accepted in 1951 with the signing of the ANZUS agreement , protection under the so-called Nuclear umbrella ( atomic screen ) of the United States to get. The aim of this agreement was, after Japan's surrender at the end of the Second World War , to be able to jointly protect oneself from possible aggression from the Asian region. But when France began its atomic bomb tests on the Mururoa Atoll in 1966, a strong protest movement against it formed in New Zealand. In 1972 Greenpeace started from New Zealand to the French nuclear test area and from there carried the protest out into the world. A year later, New Zealand and Australia together filed a lawsuit against France in the International Court of Justice , and dispatched two warships to protest in the nuclear test area. But this only resulted in France moving its tests below the surface from then on.

In August 1976 and August 1983, anti-nuclear protests were also directed against nuclear-powered American warships such as the USS Truxtun and USS Texas , which were not very welcome in the ports of Wellington and Auckland. However, when the New Zealand government refused entry into New Zealand territorial waters on February 1, 1985, the US warship USS Buchanan , the US government reacted angrily and in turn put the ANZUS treaty on hold. To this day, relations between the two countries in this area are considered tense. On July 10 of the same year, the French secret service sank the Greenpeace ship Rainbow Warrior in the port of Auckland with two explosive charges and murdered a Dutch journalist.

To the New Zealand attitude towards nuclear power and against nuclear weapons to give a legal basis which was supported by the at that time located in government Labor Party on June 8, 1987, the New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament and Arms Control Act ( disarmament and arms control law and the Declaration of New Zealand nuclear weapons-free zone ). A 1969 poll found that 52% of all New Zealanders would rather break a defense treaty than accept ships carrying nuclear weapons in New Zealand waters.

Opening up to Asia

When the British market collapsed when Great Britain joined the EC, a new orientation began in New Zealand. Until 1973, despite the immense distance, the economic and political focus was on the former mother country, now it was important to think about which part of the globe you were actually on and which markets could be reached within shorter distances. Trade relations with Australia had existed since colonial times, but these could not replace the lost markets. What New Zealand urgently needed were skilled workers, especially since British citizens became more difficult to enter from 1973. Furthermore, there was a lack of capital and new sales markets. The Labor government under David Lange made a start in this direction in 1984. In 1986 New Zealand joined the GATT negotiations of the Uruguay Round and in 1989 joined the Asia-Pacific Economic Community (APEC).

In 1991, the National Party's Immigration Amendment Act was intended to facilitate the immigration of skilled workers and start-ups. But immigration from the Asian region exceeded all expectations with more than 50% of all immigration and in the 1990s led to partly racially discriminatory behavior by New Zealanders. On the other hand, Asia took on an increasingly stronger and more accepted role for the New Zealanders in the area of trade. In 1988 New Zealand's imports from the People's Republic of China were just 1%. In 2007, 13% of all goods came from China and all important Asian trading partners such as PR China, the Republic of China (Taiwan) , Hong Kong and South Korea combined; in the same year they shared 13% of New Zealand exports and 19% of imports.

In the meantime, New Zealand has recognized the importance of Asia for its economic and cultural development. In addition to a 14.6% Māori population and 6.9% immigrants from the Pacific islands, people of Asian origin now make up more than 9.2% (2006) . That is why New Zealand often puts its cultural diversity in the foreground and likes to present itself as a multicultural country, as well as a country of immigration. Among other things, the education sector benefited from this development. Many young people came from Asia in particular to study in New Zealand. Education was so u. a. an export hit. But in order to be able to also secure New Zealand's economic impact on Asian markets, the Prime Minister signed Helen Clark in April 2008 after three years of negotiations, the New Zealand-China Free Trade Agreement ( FTA ), estimated export volume from 225 to 350 million NZ $ . At the same time, New Zealand opened its borders to around 1,800 Chinese skilled workers and 1,000 holiday workers.

See also

literature

- Giselle Byrnes (Ed.): The New Oxford History of New Zealand . Oxford University Press , Melbourne 2009, ISBN 978-0-19-558471-4 (English).

- WH Oliver, BR Williams (Ed.): The Oxford History of New Zealand . Oxford University Press , Wellington 1981, ISBN 0-19-558062-1 (English).

- Edmund Bohan : New Zealand - The Story so far - A short History . HarperCollinsPublishers (New Zealand) Ltd. , Auckland 1997, ISBN 1-86950-222-1 (English).

- Tom Brooking : The History of New Zealand . Greenwood Press , Westport, Connecticut 2004, ISBN 0-313-32356-9 (English).

- Alison Drench : Essential Dates - A Timeline of New Zealand History . Random House , Auckland 2005, ISBN 1-86941-689-9 (English).

- John Parker : Frontier of Dreams - The Story of New Zealand . Scholastic New Zealand Ltd. , Auckland 2005, ISBN 1-86943-680-6 (English).

- Christina Anette Dölling: New Zealand - A Nation of Immigrants . Deutscher Wissenschafts-Verlag (DWV), Baden-Baden 2008, ISBN 978-3-935176-85-9 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Parker : Frontier of Dreams - The Story of New Zealand . 2005, p. 6 .

- ^ JJ Aitken : Plate Tectonics for Curious Kiwis . Ed .: Institute of Geological & Nuclear Sciences Ltd. . Lower Hutt 1996, ISBN 0-478-09555-4 , pp. 38 (English).

- ^ Parker : Frontier of Dreams - The Story of New Zealand . 2005, p. 7 .

- ^ Peter Bellwood, Eusebio Dizon : Austronesian cultural origins . In: Past Human Migrations in East Asia . Routledge , Abingdon, Oxon, UK 2008, ISBN 0-415-39923-8 , pp. 23–39 (English, online [PDF; accessed July 22, 2010]).

- ↑ Edited by Patrick V. Kirch : Dating the late prehistoric dispersal of Polynesians to New Zealand using the commensal Pacific rat . In: The National Academy of Sciences (Ed.): PNAS . Volume 105, No. 22 . Washington June 3, 2008 ( online [accessed July 28, 2010]).

- ^ Ideas of Māori origins - 1920s – 2000: new understanding . Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand , accessed July 22, 2010 .

- ↑ Ideas of Māori origins - 1840s – early 20th century : Māori tradition and the Great Fleet . Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand , accessed July 22, 2010 .

- ^ Dölling: New Zealand - A Nation of Immigrants . 2008, p. 45 .

- ^ Parker : Frontier of Dreams - The Story of New Zealand . 2005, p. 35 .

- ↑ Morten Erik Allentoft and eight other authors: Extinct New Zealand megafauna were not in decline before human colonization . In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . Vol.111 No.13 , April 1, 2014, p. 4922–4927 , doi : 10.1073 / pnas.1314972111 (English, online [accessed November 17, 2017]).

- ↑ EG Schwimmer: Warfare of the Maori . In: Maori Affairs department (ed.): TE AO HOU The New World . Volume 9 (No.4), No. 36 . Wellington September 1961, p. 52-55 ( online [accessed July 24, 2010]).

- ↑ Tales of Maori cannibalism told in new book . stuff.co.nz , August 5, 2008, accessed July 24, 2010 .

- ↑ Gilsemans, Isaac: A view of the Murderers' Bay, as you are at anchor here in 15 fathom [1642]. Alexander Turbull Library, Wellington , accessed July 26, 2010 .

- ^ The first meeting - Abel Tasman and Māori in Golden Bay . The Prow, Nelson , accessed July 26, 2010 .

- ^ European discovery of New Zealand - Tasman's achievement . Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand , accessed July 26, 2010 .

- ^ European discovery of New Zealand - James Cook . Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand , accessed July 26, 2010 .

- ^ Joseph Angus Mackay : History Poverty Bay . Ed .: JA Mackay . Gisborne 1949, p. 17th ff . (English, online [accessed July 26, 2010]).

- ^ Dölling: New Zealand - A Nation of Immigrants . 2008, p. 47 .

- ^ Dölling: New Zealand - A Nation of Immigrants . 2008, p. 48 .

- ^ John Dunmore : French Explorers in the Pacific . The nineteenth century . In: The New Zealand Geographical Society Inc. (Ed.): New Zealand Geographer . Volume 28, No. 1 . Auckland 1972, p. 106 ff . (English).

- ^ European discovery of New Zealand - French explorers . Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand , accessed July 26, 2010 .

- ^ Robert McNab : From Tasman To Marsden - A History of Northern New Zealand from 1642 to 1818 . J. Wilkie & Co. Ltd. , Dunedin 1914, p. 80 (English).

- ^ Robert McNab : From Tasman To Marsden - A History of Northern New Zealand from 1642 to 1818 . J. Wilkie & Co. Ltd. , Dunedin 1914, p. 98 (English).

- ^ Brooking : The History of New Zealand . 2004, p. 27 .

- ^ Russell - History . Russell Centennial Trust Board Trustees , accessed July 28, 2010 .

- ^ Brooking : The History of New Zealand . 2004, p. 32 .

- ^ Dölling: New Zealand - A Nation of Immigrants . 2008, p. 50 .

- ^ Brooking : The History of New Zealand . 2004, p. 34 ff .

- ^ The 1835 Declaration of Independence . (Flashplayer) New Zealand History Online , accessed July 30, 2010 (English, the document to be viewed is in Māori .).

- ^ JMR Owens : New Zealand before Annexation . In: The Oxford History of New Zealand . Oxford University Press , Wellington 1981, pp. 50 ff . (English).

- ^ WJ Gardner : A Colonial Economy . In: The Oxford History of New Zealand . Oxford University Press , Wellington 1981, pp. 59 ff . (English).

- ↑ Bohan : New Zealand - The Story so far - A short History . 1997, p. 34 f .

- ^ Jörg Baten: A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the present . Cambridge University Press , 2016, ISBN 978-1-107-50718-0 , pp. 287 (English).

- ^ New Zealand Timeline: 1840-1900 . The Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry , archived from the original on May 22, 2010 ; accessed on November 29, 2015 (English, original website no longer available).

- ^ History of immigration - Depression: 1885 to 1900 . Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand , accessed August 3, 2010 .

- ^ Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 115.

- ^ Women and the Vote. New Zealand History, accessed June 30, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Women and the Vote. New Zealand History, accessed June 30, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Women and the Vote. New Zealand History, accessed July 1, 2019 .

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 277.

- ^ History of immigration - Between the wars . Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand , accessed August 3, 2010 .

- ↑ Mark Price : Dunedin family's pride as soldier honored . Otago Daily Times , February 3, 2009, accessed December 17, 2011 .

- ↑ Drench : Essential Dates - A Timeline of New Zealand History . 2005, p. 129, 135, 167, 191 .

- ^ New Zealand and the Second World War . New Zealand History Online , accessed August 4, 2010 .

- ↑ Andrew Sharp : Constitution . In: New Zealand Government and Politics . 3. Edition. Oxford University Press , South Melbourne 2003, ISBN 0-19-558464-3 , Part B The Political System, pp. 43 (English).

- ^ History . New Zealand Parliament , accessed August 4, 2010 .

- ^ The first Waitangi Day . New Zealand History Online , accessed August 5, 2010 .

- ↑ Janine Hayward : The Waitangi Tribunal in the Treaty Settlement Process . In: New Zealand Government and Politics . 3. Edition. Oxford University Press , South Melbourne 2003, ISBN 0-19-558464-3 , Part D Public Policy, pp. 514 ff . (English).

- ^ Colin James : The Rise and Fall of the Market Liberals in the Labor Party . In: The Labor Party after 75 Years . Victoria University of Wellington , Wellington 1992, p. 11 ff . (English).

- ^ Nuclear-free New Zealand . New Zealand History Online , accessed on August 5, 2010 (a total of seven websites on the subject).

- ^ New Zealand becomes nuclear free . New Zealand History Online , accessed August 5, 2010 .

- ^ Dölling: New Zealand - A Nation of Immigrants . 2008, p. 107, 122 .

- ↑ Diversification since 1990 . Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand , accessed August 5, 2010 .

- ↑ Historic first as New Zealand-China FTA signed . Scope Parliament , April 7, 2008, accessed August 5, 2010 .