Elsterwerda-Grödel raft canal

| Elsterwerda-Grödel raft canal | |

|---|---|

|

The raft canal between Elsterwerda and Prösen |

|

| location | Germany: Brandenburg, Saxony |

| length | 21.4 km, of which 15.45 km in Saxony |

| Built | 1742 to 1748 |

| Beginning | On the Elbe near Grödel ⊙ |

| The End | At the Pulsnitz in Elsterwerda ⊙ |

| Descent structures | Elsterwerda, Prösen, Gröditz, Pulsen |

The Elsterwerda-Grödel-Floßkanal is an 18th century waterway that connects the Pulsnitz in Elsterwerda with the Elbe near Grödel .

The original purpose of the channel used in the present primarily to recreational purposes was the high demand for wood in the room Dresden / Meissen from the forests around the time still to Saxony belonging Elsterwerda (now Brandenburg to cover). It was built on the personal orders of the Saxon Elector. Later, until shipping was discontinued in 1942, it was primarily used as a transport route for the Gröditz ironworks . To transport were Bomätschern drawn barges used. From the 1960s until the fall of the Wall it was used as an irrigation canal.

Geographical location, natural space, flora and fauna

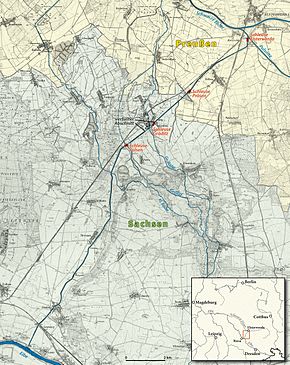

The Elsterwerda-Grödel-Raft Canal is located in the eastern Elbe-Elster area . Starting at an artificially created basin in Grödel , Saxony, right next to the Elbe, the canal runs in a north-easterly direction through the western Grossenhainer Pflege to the Schraden to the Holzhof in Elsterwerda, Brandenburg .

Between Pulsen and Gröditz, the canal crosses the three estuary arms of the Großer Röder , from which it is fed. In the area of the city of Gröditz, the canal has now been backfilled over a length of about one kilometer, which means that it is now divided into two sections. While the southern section in Gröditz flows into the Große Röder via a pipeline, the northern part is supplied with water via another pipeline from the Große Röder. In Elsterwerda there is a connection to the Pulsnitz shortly before it flows into the Black Elster a little later .

Its width averages around 7 to 9 meters. The length is 21.4 kilometers, of which 15.45 kilometers are on Saxon territory. Six widened passing points were created along the entire route, where barges could meet. In its course it touches the places Glaubitz , Radewitz , Marksiedlitz , Streumen , Wülknitz , Koselitz , Tiefenau , Pulsen , Gröditz , Prösen and finally Elsterwerda . In doing so, it crosses under the Riesa-Dresden railway line and the 98 trunk road in Glaubitz, the 169 trunk road in Prösen and the Berlin-Dresden train track in Elsterwerda .

In Elsterwerda there is a small section of the raft canal in the area of the 484 square kilometer Niederlausitzer Heidelandschaft nature park , the centerpiece of which, the Forsthaus Prösa nature reserve , houses one of the largest contiguous sessile oak forests in Central Europe. The canal itself has a rich fish population. There are also occurrences of the endangered Elbe beaver , a rare subspecies of the European beaver, along the canal . Furthermore it forms the habitat and breeding area of various water birds.

The flora in the water includes numerous floating and diving plants, such as horn leaf , milfoil , water and pond lenses , pond roses and spawning herbs . Up to now, in addition to the reeds that are very abundant in places , bush carnations , alpine vermin and gentian have also been detected in the riparian zones .

Surname

The name of the vernacular colloquially neighboring communities mostly just channel waters mentioned was in the past and is very varied in the present. In historical maps, writings and documents, in addition to the name Elsterwerda-Grödel-Raft Canal, there are a number of different names for the structure.

While the anniversary volume of the Heimatvereine Elsterwerda and Gröditz, published in 1997, was published under the name 250 years of the Grödel-Elsterwerda raft canal , in 1912 the body of water was named in the New Archives for Saxon History and Archeology , a specialist journal for Saxon regional history, and again the Elsterwerda - Grödel raft canal . In the map of the German Empire published by Perthes in Gotha in 1907 and in the Vienna Peace Treaty of 1815 (Article 17), the canal is referred to as the Elsterwerdaer Floßgraben . Alfred Hettner's Geographische Zeitschrift from 1898 calls it the Grödel-Elsterwerdaer Floßkanal . Under this name it is also in their 2001 Volume 63 The Schraden the publication series values of the German homeland described. The Riesa river management authority still calls the canal that way today. Meyer's Konversations-Lexikon of 1885 and Petermann's Geographische Mitteilungen , published in 1902, described him as Grödel-Elsterwerda Canal .

Other common variants were and are among others the Grödel-Elsterwerda raft canal , Elsterwerda-Grödeler raft canal , Elbe-Elster-raft canal , Elster-Elbe-Canal , Elbe-Elster canal and also raft canal .

Historical development and use of the raft canal

A residential city needs wood

Under the Saxon Elector Friedrich August I , also known as August the Strong, building activity had started in the Dresden / Meißen area. August had his royal seat on the Elbe developed into one of the most magnificent in Europe. In addition to the Dresden Neustadt , numerous other buildings and the porcelain factory in Meißen were built . In addition, the city of Dresden recorded strong population growth. In the years from 1648 to 1699 alone, the population rose by a third from 16,000 to 21,298. By 1755 it should triple to 63,209 inhabitants. There was therefore a steadily increasing demand for wood. Since the Ore Mountains were already largely exploited and the Bohemian wood was expensive, one thought of the huge forest areas in the north of the electorate. The Grünhauser Forest , the Liebenwerdaer Heide , the Plessaer Heide and the Schradenwald were located here, south of Finsterwalde . Most of these were owned by the state, but so far they were mainly used for hunting and were therefore largely untouched at the time.

The Black Elster and the Pulsnitz were the largest bodies of water flowing through this area. Although the Pulsnitz had been largely straightened in the lower course for amelioration purposes by the construction of the new Pulsnitzgraben since the 16th century , the Black Elster flowed through the lowland in numerous small, winding branches. A regulated rafting operation was therefore only possible below the town of Liebenwerda , which in turn made it necessary to first raft the wood to the Elster estuary at Jessen and then transport it back up the Elbe.

A connection still to be created between the Black Elster and the Elbe seemed best suited to bring the coveted raw material to the royal seat by the shortest route . The first plans for the project to connect the two rivers were undertaken as early as 1702 at the personal order of the elector. However, the preliminary planning and investigations should still take several decades to complete.

After the first construction tests of a raft ditch , the so-called main raft ditch with a length of 26 kilometers was realized some time later. The main raft ditch was fed by three tributaries. They began in the woods south of Finsterwalde, near the now devastated town of Gohra , south of Lichterfeld and at Mahlenzteich near Nehesdorf . The tributaries then merged at Sorno . From here the main raft ditch ran across Oppelhain, across the eastern Liebenwerda and Plessa heaths to the Schwarze Elster near Plessa and on to Elsterwerda. This construction project was relatively uncomplicated because the builders had already gained experience in similar projects in Saxony in the past. The raft ditch was finally completed in 1743 and put into operation the following year.

The project in the section between the Schwarzen Elster and Elbe became more delicate. The water level at the planned estuary area in the Elbe was higher than in Elsterwerda. In simple raft ditches, however, the wood was moved or drifted in the direction of flow of the water . Therefore, a canal had to be built instead , which overcame the height differences using locks. Engineer Johannes Müller , who was commissioned with the preliminary investigations, presented the first drafts in 1727. Because of the numerous investigations, calculations and tests, the start of construction was finally postponed again by over a decade, because the construction was supposed to be profitable. There were also heated discussions about the route; a line from Prieschka to Stehla had also been considered, but was met with fierce resistance from unspecified influential personalities who, among other things, considered this route too costly. The route between Elsterwerda and Grödel has also been changed several times. The construction of the canal did not begin until after Augustus the Strong died in 1733, in 1742 under Elector Friedrich August II.

Müller himself, who had previously been entrusted with the construction of the main raft ditch, was commissioned to carry out the construction. The canal was scheduled to be completed in 1744. However, the implementation encountered numerous obstacles. The excavation work was very time-consuming, finding sufficiently reliable workers proved difficult, the connection to the Elbe and the Prösener lock caused problems. Because of the unfavorable subsoil - the designers had to struggle with alluvial sand there - this lock had to be replaced several times and it was not until 1767 that it worked satisfactorily. Ultimately, they did not have a direct connection to the Elbe.

After six years of construction and after it had been flooded shortly before, on December 2, 1748, the first two barges pulled by bombers finally passed the completed canal on a test run. It took place in the presence of a state canal commission and the raft master Schubert, who had been appointed in the meantime, and lasted twelve hours, with an interruption in Prosen. The cost of the project totaled 65,437 thalers , significantly more than the 52,610 thalers originally approved for construction. In addition there were 5800 thalers for the raft ditch.

Division of the channel

The problems at the Prösener lock persisted and the canal therefore had to be shut down several times. But the supply of wood in the sales area improved after the construction, because the Bohemian wood became cheaper.

The canal took on a completely different meaning two decades after it opened. As early as 1725, under the influence of Baroness Benedicta Margareta von Löwendal, an ironworks was built in the Mückenberg domain , the so-called Lauchhammerwerk . In doing so, she laid the foundation stone for one of the first industrial companies in the region, which was to have a major impact on it in the years that followed. The noblewoman, who died in 1776 without direct descendants, bequeathed her property to her godchild Detlev Carl von Einsiedel , who owned the Saathain estate, some 20 kilometers to the west . He recognized the economic potential of the raft canal and in 1779 opened another hammer mill in the Saathain village of Gröditz an der Röder. The water required for its operation was supplied in abundance by the Große Röder, which passed Gröditz, and the plant soon received the concession to use the canal for the transport of goods.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Napoleonic Wars hit Europe . The Kingdom of Saxony , which had existed since 1806, had stood on the side of the loser Napoleon . As a result of the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Saxony was divided and large parts of its national territory had to be ceded. The new border ran in the region along the road from Mühlberg to Ortrand . The communities on the road fell to Prussia . North of Gröditz, it crossed the course of the raft canal and divided it into a Prussian section in the north and a somewhat larger Saxon section in the south. The ironworks in Gröditz was now separated from its main plant in Mückenberg by a state border and Saxony no longer had access to the forests north of the canal. State Secretary Detlev von Einsiedel , who negotiated for the country , succeeded in having free navigation and rafting on the canal agreed in writing in the Vienna Peace Treaty, but in the smaller Prussian section in particular, the transport route then largely lost its importance for freight transport. And when the Prussian State Office No. 62 , which crossed the canal and was to serve as the post road from Berlin to Dresden, was set up at the Holzhof in Elsterwerda, it was quickly filled in. In 1833 the timber transports were then completely stopped.

Renewal of the canal and its structures

As early as 1827, Count von Einsiedel was able to obtain a new concession on the Saxon side in the form of a privilege to use the canal. When this privilege expired some thirty years later, the canal in the Gröditz – Grödel section was opened to general traffic in 1861. In the meantime, numerous repairs and renovations had become necessary. The political situation has meanwhile made it possible to put the northern section back into operation, and so the locks on the canal were renewed or rebuilt from 1865 to 1869, so that its entire length was finally navigable again.

After this restoration, the canal was also opened to general traffic in Prussia. On April 8, 1869, a new canal order came into force on both sections. Initially, this also had the desired effect and the goods transport carried out on the canal increased noticeably. But in the meantime the region had become more industrialized. The numerous new lignite mines in particular needed fast and efficient transport connections. In 1875, the Berlin – Dresden and Elsterwerda – Riesa railway lines were built, which followed suit. While the former crosses the canal in Elsterwerda, the route towards Riesa runs largely parallel to the canal. The railroad made the previous freight transport on the raft canal considerable competition, and it soon lost its importance.

The main function of the canal remained the management of the Gröditz steelworks. Almost only the Saxon section was used. Rubble and slag came from the steel mill . On the way back, sand and clay were transported . These raw materials mostly came from pits located between Koselitz and Radewitz, for which special light rail lines were laid to the canal, on which tipping lorries operated. The canal also served as a collecting basin for the cooling water required in the plant. As early as 1912, K. Mende reported in an essay that appeared in the local history supplement “Die Schwarze Elster” in the “Liebenwerdaer Kreisblatt”: “A transverse dam has been drawn through the Gröditzer Schleuse, which holds the Röder water in the canal towards the Elbe.” While the Pulsener Schleuse was still in operation at the time, the northern section was hardly used any more. Between Gröditz and Prösen it was almost entirely overgrown with reeds.

The vision of an Elbe-Oder canal

Despite the competition from the railways, waterways continued to be in focus as transport routes. Shortly after the raft canal was built, plans were made to extend it to the Spree. The motif of these mind games was again the procurement of wood. The authorities therefore commissioned the well-proven Johann Müller again in 1754 to carry out the first preliminary investigations for the project. In the same year he submitted his first plans and map sketches for the project. However, the plans were accompanied by the remark by the Dresden raft inspector Fink, “It is a far-reaching project that will cost a lot of guilders” , whereupon they were not pursued any further.

At the beginning of the 20th century, experts took up the former ideas again. There were plans to build a large shipping canal that would connect the Elbe to the Oder via the Black Elster and the Spree . This was intended for cargo ships up to 1000 tons, a length of 80 meters, a width of 9.2 meters and a draft of 1.75 to 2.00 meters and above. Sections of the Elsterwerda-Grödel raft canal and the Schraden area should also be included in the options being considered. In January 1928 , a canal construction office was set up in Senftenberg , whose lignite mining area would have benefited most from the canal, but the construction of the shipping lane did not take place in the end and the projects did not get beyond the planning stage up to the Second World War.

The end as a transport route and economic use

By the early 1930s, the steel mill had grown so much that it became necessary to expand its production facilities across the canal. That is why the canal in the factory area, which was hardly used anyway, was quickly filled in in the period 1934/35. This took place again in 1940/41. And the last barge passed the canal a short time later on July 24, 1942.

This ended its use as a traffic route. From then on he mainly supplied water to the industrial companies located on the canal. In the 1950s there were again very specific plans to build a shipping lane using the raft canal as far as the Elbe, which among other things also provided for a port at the Gröditz steelworks, but this project was also put on record.

The last major use of the canal so far came from the end of the 1960s. With the intensification of agriculture in the area of the former GDR, the canal from the Elbe to the weir on the Kleine Röder was once again used to irrigate the adjacent fields and meadows. From the canal, the water was spread onto the surrounding fields via huge irrigation systems. The pipe systems had a total length of more than 178 kilometers. These were fed by pumping stations built on the canal. The water also came through a system of ditches into Spansberg , west of Gröditz , where, in addition to a storage basin, there were other pumping stations. In Grödel, the water was lifted into the canal's basin by a Hungarian-made pumping station floating on the Elbe. Up to 2.4 cubic meters per second could be conveyed. A total of 5176 hectares were irrigated. In 1989 6.2 million cubic meters of water were taken from the Elbe; the maximum daily output was 113,200 cubic meters.

With the economic upheaval in the time of reunification , this use also came to an end at the beginning of the 1990s, because the agricultural production cooperatives dissolved and there was no longer an operator for the operation of the huge plant, which required a lot of labor.

Effects of the canal construction on the region

The construction of the canal significantly improved the region's transport links. Even if the project was not originally intended for this and there were often disputes about the then scarce water in the Röder during the summer dry seasons, the neighboring communities and the entire region also benefited in the end. Manpower was needed to manage the canal, and larger quantities of material or merchandise could be transported quickly and reasonably inexpensively using the waterway that was now available. The canal was soon used by the population as a fishing ground. After the transports on the canal had declined, a fishing cooperative was founded, which parceled it out in parts and leased it. In addition, it served, among other things, as a horse pond , for iron harvest and as a bathing area.

In Gröditz, the construction of the raft canal initiated the industrial development of the place. The community, which previously only consisted of a few houses, grew, as did some surrounding communities, primarily as a result of the steelworks located here, which led to further industrial settlements. In 1836 Gröditz only had 150 inhabitants, and shortly before the Elsterwerda – Riesa railway line was built, it was 545. The community continued to grow and in 1967 it was granted city rights. For the following year 1968, Gröditz had 8100 inhabitants and the population continued to grow until the end of the 1980s to over 10,000.

After the canal was built, the place Langenberg and the place Marksiedlitz emerged again, which had previously fallen desolately .

The historic infrastructure of the canal

The staff working on the raft canal, such as the timber instructors and administrators employed at the Elsterwerda and Grödel timber yards, the lock pullers and the bomber, were subordinate to the raft master. The chief raft inspector, the chief raft inspector and the raft director were superordinate to this. After the division of Saxony or after the new canal regulations came into force on May 1, 1869, the upper supervision in the Saxon section was the responsibility of the hydraulic engineering inspector in Riesa and in the Prussian area the building inspector in Herzberg . They also had to ensure compliance with the canal order, which stipulated, among other things, canal interest, lock fees and ship dimensions.

The logs came mainly via various ditches, such as the main raft ditch, the Pulsnitz and the Schwarze Elster through the Schraden to the Holzhof in Elsterwerda. It was stored, split into logs and loaded onto the barges that then to its destination, first mostly the lumberyard in Grödel, towed were. The freight was again temporarily stored at the Grödeler Holzhof or reloaded onto the ships and barges operating on the Elbe.

The barges, which were specially built for transporting timber, were hauled out on the canal by a five-man crew, a helmsman and four ship pullers. They had a capacity of about 200 cubic meters of wood, were 26 meters long and about 3.25 meters wide. Her draft was 0.95 meters. When the waterway was later used for general cargo and bulk cargo , other types of construction were used, which had a capacity of around 25 tons. These were only about 19 meters long. At the beginning of the 20th century, motor ships were also used for transport.

The canal, which required a water depth of around 1.5 meters to operate, was fed by the three mouths of the Große Röder - the Große Röder itself, the Kleine Röder and the Geißlitz. The Kleine Röder with the highest water level of the three supplied the canal's apex.

In the northern part this function was initially taken over by the Pulsnitz, which, however, caused further problems with the drainage of the already swampy Pulsnitz lowlands in the Schraden, so that the construction of a fourth lock soon became necessary here. These problems also existed in the area where the canal crossed the Röder. Originally they made do with three drainage ditches for the site, which were led under the canal by means of culverts , so that no pumps were required.

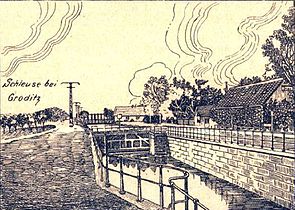

The height differences between the Pulsnitz or the Schwarzen Elster and the Elbe were initially overcome by means of three wooden chamber locks that were built in Prösen (2.80 m), Gröditz (2.25 m) and Pulsen (0.65 m). As a result of the ongoing problems at the lock in Prösen, it was made of stone in 1755 and renewed again in 1766/67. A fourth lock in Elsterwerda was added in 1766. The chamber locks had a usable length of 42.70 meters. They were 8.70 meters wide, the lock openings on both sides 5.70 meters. A lock usually took 12 minutes.

Originally it was planned to connect the canal to the Elbe by means of a double lock, so that the canal barges could have continued as barges on the Elbe. Opponents of the Prieschka – Stehla section had feared, among other things, that the locks would be badly affected by the regular flooding of the river. The predicted problem actually occurred at the construction site in Grödel. Unusually strong ice rides and a dam break near Nünchritz caused great damage during the construction period and increased costs. Ultimately, the structural difficulties appeared so serious that the lock was not built; instead, a basin was built directly on the Elbe.

Current use for recreational purposes

The raft channel has had the status of a monument since 1978 . In terms of water management, it is hardly of any importance. Today it is mostly used for recreation and fishing . The Riesa river management in Saxony is responsible for the water maintenance of the canal , which also maintains a depot in the area of the Pulsen lock. Here it is a first order body of water . In Brandenburg, where it belongs to the second order, the Kleine Elster - Pulsnitz water association is responsible.

The oldest sports facility in the small town is now located on the grounds of the Elsterwerdaer Holzhof . After becoming a popular excursion destination in the middle of the 19th century, several sports facilities were built here in the first third of the last century, which were extensively expanded and expanded in the following period.

In order to get a historical insight into the history of the canal, reconstruction work was carried out on the lock in Prösen and the wooden lock gates were rebuilt. As with everyone else, they had not been there for a long time. In the immediate vicinity was the former lock keeper's house, which was demolished in 1954 due to dilapidation. At its original location there is now a gastronomic facility. In 2001, therefore, a replica of the local lock keeper's cottage was built not far from the lock, in the vicinity of which an exhibition on the history of the “raft canal” with two replicas of the barges operating here and some display boards could be seen for a long time.

Several interrupted bike paths run parallel to the canal, some of them on the dam. The paths with the raft canal route , a cycle path that connects the Elbe cycle path from Grödel with the Schwarze-Elster cycle path , are developed for tourists . The former towpath can still be seen on a few kilometers of the banks of the water . Other still perceptible relics of the canal's history are widened sections for the encounter of barges, the remains of the locks in Elsterwerda and Pulsen and in Grödel two vaulted bridges from the time the canal was built. In places, the foundations of the overhead power line that once ran along the canal can still be seen, which is considered to be the first high-voltage line in Europe with an operating voltage of over 100 kV. There is a historic boundary stone on the Saxon-Brandenburg border.

Other attractions in the area include the Elsterwerda Castle , the Koselitz ponds, the Tiefenau baroque garden with a preserved castle church and the estate park in Grödel. In addition, at Glaubitz, Streumen and Zeithain four obelisks made of sandstone that characterize the landscape have been preserved, which marked the terrain of the Zeithain pleasure camp in the 18th century .

Publications and Media

Literature (selection)

- Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Heimatkunde e. V. Bad Liebenwerda (Hrsg.): Home calendar for the country between the Elbe and Elster. No. 54 , Gräser Verlag, Großenhain 2001, ISBN 3-932913-22-1 (article by Werner Galle and Ottmar Gottschlich: Der Elsterwerdaer Holzhof , pp. 83-88)

- Herbert Flügel: On the construction history of the Elsterwerda - Grödel raft canal in: Sächsische Heimatblätter , issue 2/1987, pp. 72–77

- Heimatverein Elsterwerda und Umgebung e. V., Heimatverein for research into the Saxon steelworks-Gröditzer Stahlwerke GmbH (publisher): 250 years of the Grödel-Elsterwerda raft canal 1748–1998 , Lampertswalde 1997.

- Institute for regional geography Leipzig, Saxon Academy of Sciences in Leipzig (Hrsg.): Der Schraden. A geographical inventory in the area of Elsterwerda, Lauchhammer, Hirschfeld and Ortrand , landscapes in Germany - values of the German homeland, vol. 63, Böhlau, Cologne a. a. 2001, ISBN 3-412-10900-2 .

- Eberhard Matthes, Werner Galle: Elsterwerda in old views . 2nd ed., European Library, Zaltbommel (Netherlands) 1993, ISBN 90-288-5344-8

- Gerhard Richter: 250 years of the Grödel – Elsterwerda raft canal in: Messages from the Landesverein Sächsischer Heimatschutz e. V., Issue 3/1997, pp. 49-54.

- Günter Krieg: Forays through Niederlausitz and the Elbe-Elsterland. , Volume 19. The Grödel-Elsterwerdaer Raft Canal between Elbe and Elster. Self-published by Günter Krieg, Doberlug-Kirchhain 2003, DNB 978790715 .

Documentaries (film)

- Hans-Georg Wosseng: The rain makers from Wülknitz - people are changing their country - the country is changing its people , television documentary on behalf of the DFF about the melioration object in the Riesa canal area, production: DEFA -Studio for short films, Babelsberg , 1977

Web links

- Entry in the monument database of the State of Brandenburg

- Internet presence of the Elbe-Röder-Dreieck e. V , association for the promotion of regional development in the Elbe-Röder-Dreieck region.

- Internet presence of the city of Elsterwerda

- Internet presence of the municipality of Röderland

Footnotes and individual references

- ↑ a b c d Luise Grundmann, Dietrich Hanspach (author): Der Schraden. A regional study in the Elsterwerda, Lauchhammer, Hirschfeld and Ortrand area . Ed .: Institute for Regional Geography Leipzig and the Saxon Academy of Sciences in Leipzig. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne, Weimar, Vienna 2005, ISBN 3-412-10900-2 , pp. 101/102 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Willy Handrack, Ernst Fischer: The Grödel-Elsterwerda raft canal - a technical monument from the 18th century . In: 250 years of the Grödel-Elsterwerda raft canal 1748–1998 . Lampertswalde 1997.

- ^ Tilo Jobst: Flora and fauna of the Grödel-Elsterwerda raft canal . In: 250 years of the Grödel-Elsterwerda raft canal 1748–1998 . Lampertswalde 1997, p. 80-83 .

- ^ W. Baensch :: New archive for Saxon history and archeology . 1912. ( digitized version )

- ↑ a b Print: Peace treatise between Ihro Königl. Majesty of Saxony etc. and Ihro Königl. Majesty of Prussia etc. completed and signed at Vienna the 18th, and ratified on May 21st, 1815, Dresden [1815]. in the state archive of Saxony-Anhalt

- ^ Alfred Hettner : Geographical journal . GB Teubner, 1898. ( books.google.de )

- ↑ a b The Riesa river management on the homepage of the state dam administration of the Free State of Saxony; accessed on March 21, 2014

- ↑ Grödel-Elsterwerda raft canal . In: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon . 4th edition. Volume 7, Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1885–1892, pp. 751–751.

- ^ August Petermann: Petermanns Mitteilungen . H. Haack, 1877. ( digitized version )

- ^ Announcements from the Society for Geography in Leipzig . Duncker & Humblot, 1904 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Luise Grundmann, Dietrich Hanspach (author): Der Schraden. A regional study in the Elsterwerda, Lauchhammer, Hirschfeld and Ortrand area . Ed .: Institute for Regional Geography Leipzig and the Saxon Academy of Sciences in Leipzig. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne, Weimar, Vienna 2005, ISBN 3-412-10900-2 , pp. 198 .

- ^ A b Luise Grundmann, Dietrich Hanspach (author): Der Schraden. A regional study in the Elsterwerda, Lauchhammer, Hirschfeld and Ortrand area . Ed .: Institute for Regional Geography Leipzig and the Saxon Academy of Sciences in Leipzig. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne, Weimar, Vienna 2005, ISBN 3-412-10900-2 , pp. 137 .

- ↑ a b c d e f K. Mende: The Elsterwerda-Grödel raft canal and its creation . In: The Black Magpie . No. 167-169 , 1912 (local history supplement to the Liebenwerdaer Kreisblatt).

- ↑ a b c d Gerhard Richter: 250 years of the Grödel – Elsterwerda raft canal in: Messages from the Landesverein Sächsischer Heimatschutz e. V., Issue 3/1997, pp. 49-54

- ↑ "On the history of Saathain Castle" . In: The Black Magpie . No. 88 , 1908.

- ^ City administration Lauchhammer (ed.): Lauchhammer - stories of a city . Geiger Verlag, Horb am Neckar 2003, ISBN 3-89570-857-7 .

- ^ Walter Döhring, Gerhard Schmidt: Einsiedel, Detlev von. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 4, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1959, ISBN 3-428-00185-0 , p. 400 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Article 15 in the main treaty of the Congress of European Powers, Princes and Free Cities gathered in Vienna, along with 17 special treaties (digital copy)

- ↑ Friedrich Stoy : When they wanted to build a waterway from the Elbe to the Spree in 1754 . In: The Black Magpie . No. 417 , 1931 (local history supplement to the Liebenwerdaer Kreisblatt).

- ↑ Heimatverein Elsterwerda and the surrounding area (ed.): 250 years of the Grödel-Elsterwerda raft canal 1748–1998 . Lampertswalde 1997

- ↑ "The planned Elbe-Oder Canal and its route through our homeland" . In: The Black Magpie . No. 262 , 1923.

-

↑ Manfred Simon: Water supply for agricultural irrigation. In: Manfred Simon, Karl-Heinz Zwirnmann: Water management in the GDR. Published by the Water Management Working Group at the Institute for Environmental History and Regional Development eV at the University of Neubrandenburg, Edition Bookmark, Friedland 2019, ISBN 978-3-941681-50-7 , pp. 242–272, here pp. 253 f;

Manfred Simon: Maintenance and expansion of water bodies and water management systems. In: Simon, Wasserbewirtschaftung in der DDR, pp. 318–327, here p. 327. - ↑ Hannes Claus: Two decades of “rain makers” in the canal area . In: 250 years of the Grödel-Elsterwerda raft canal 1748–1998 . Lampertswalde 1997, p. 55 .

- ↑ Egon Förster: Fish economy use of the Elbe-Elsterkanals . In: 250 years of the Grödel-Elsterwerda raft canal 1748–1998 . Lampertswalde 1997.

- ↑ Egon Förster: The Canal and the Village . In: 250 years of the Grödel-Elsterwerda raft canal 1748–1998 . Lampertswalde 1997.

- ↑ Egon Förster: The canal changes the environment . In: 250 years of the Grödel-Elsterwerda raft canal 1748–1998 . Lampertswalde 1997.

- ↑ Gröditz in the Digital Historical Directory of Saxony , accessed on March 12, 2014

- ^ Langenberg in the Digital Historical Directory of Saxony , accessed on March 12, 2014

- ^ Marksiedlitz in the Digital Historical Directory of Saxony , accessed on March 12, 2014

- ↑ The former location of the Gröditzer lock is in the now filled section at the entrance to the steelworks.

- ↑ The lock at Pulsen is also referred to as the Hoische lock because of the neighboring forest area of Hoische .

- ↑ List of monuments of the Elbe-Elster district ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF)

- ↑ a b Ines Klut: Raft Canal in Prösen is a permanent problem child . In: Lausitzer Rundschau , January 13, 2010

- ↑ Internet presence of the water association Kleine Elster - Pulsnitz , accessed on March 21, 2014

- ↑ Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Heimatkunde e. V. Bad Liebenwerda (Hrsg.): Home calendar for the country between the Elbe and Elster. No. 54. Gräser Verlag, Großenhain 2001, ISBN 3-932913-22-1 . Werner Galle, Ottmar Gottschlich: The Elsterwerdaer Holzhof .

- ↑ Veit Rösler: Thomas-Reinke-is-the-new-boss-of-the-Proesener-anglers . In: Lausitzer Rundschau , January 11, 2007

- ↑ Internet presence of the “Schleusenhaus” inn , accessed on March 15, 2014

- ↑ Werner Galle: From the lock and the lock house Prösen . In: 250 years of the Grödel-Elsterwerda raft canal 1748–1998 . Lampertswalde 1997.

- ↑ The raft canal route at www.elbe-roeder.de , accessed on March 27, 2014

- ↑ The documentary “Die Regenmacher von Wülknitz” on www.film-zeit.de ( Memento of the original from March 27, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed March 26, 2014