Spanish missions in California

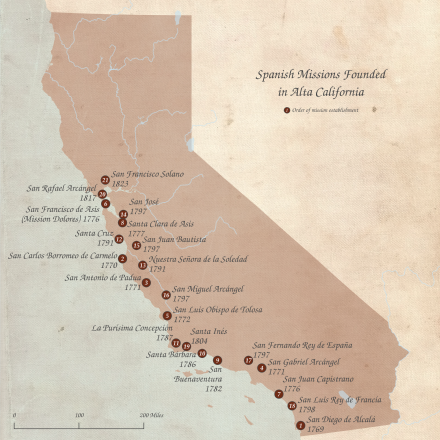

The Spanish Missions in California are a series of mission stations established by Franciscans in what is now the US state of California between 1769 and 1823 . Its purpose was, besides the evangelization of the indigenous population to Christianity , the assertion and consolidation of the ownership claims of the Spanish crown on the Pacific coast. The mission stations were the first European branches in Alta California and a milestone in the advance of the European colonial powers in the American Northwest. The Europeans brought with them their knowledge of cattle breeding , their fruits, their crops and their craftsmanship when building the stations, some of which became important economic and cultural centers . In addition to these undisputed essential contributions to the development of the region, the “civilization” of the indigenous population brought them the loss of their identity, autonomy and their living space. “Civilization” also led to a strong demographic decline .

Today the mission stations are among the oldest structures in California and are popular tourist destinations.

history

Origins

Since 1492, after the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus , the Spanish crown tried to establish mission stations in the newly discovered areas to convert the Indians to the Roman Catholic faith . Nueva España , in German New Spain , comprised the area of the Caribbean , Mexico and large parts of the southwest of today's USA. In the Bull Inter caetera of 1492, in principle, all of America was from Pope Alexander VI. Spain left to colonize. This also included the area of Alta California , which is practically congruent with today's state of California. The next year, the Tordesillas Treaty confirmed the division between Spain and Portugal almost unchanged. Antonio de la Ascensión , who had traveled to San Diego with Sebastián Vizcaíno in 1602, wrote the first reports that induced the Spanish king to colonize the area of historic California .

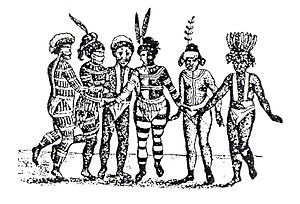

However, it was not until 1741 that it became known that the Russians were pushing into North America from the west, did the Spanish King Philip V see a conquest of Upper California as actually necessary. Sir Francis Drake had already secretly claimed North America for England for Elizabeth I , but this was without consequence. While there were twenty-one Jesuit missionaries in Baja California as early as 1721 , the north, now California, had not yet been entered. 1767 ordered Charles III. As a result of the Jesuit ban, all Jesuit missionaries were to be deported back to Spain, leaving the colonization of the north to the Franciscans, while Dominican priests took over the stations in Baja California. It is believed that there were around 300,000 Indians living in Upper California at that time , distributed among around 100 different tribes, but the information varies considerably between different authors.

Missions (1769-1833)

Gaspar de Portolà undertook the first overland expedition to Alta California in 1769. Junípero Serra , a Franciscan who was involved in Portolà's expedition, founded the first mission station in San Diego . As they moved on in search of Monterey Bay , Fathers Francisco Gómez and Juan Crespí (1721–1782) came through a settlement in which two young girls were dying. The first, still a toddler, was baptized by Gómez with the name "Maria Magdalena", while Crespí named the other, who suffered from severe burns, the name "Margarita". These were the first baptisms in Upper California. The expedition participants called the place "Los Cristianos". Portolà's expedition reached San Francisco Bay in 1769 , but missed Monterey. It wasn't until a year later, on the next trip north, that the explorers found the Bay of Monterey they were looking for and founded the second station there.

Over the next few years, under the leadership of Father Junípero Serra, a total of 21 mission stations were established from San Diego to Sonoma north of San Francisco . The individual stations are each a day's ride , i.e. around 50 kilometers, apart and form El Camino Real , the “royal road”.

Actually, according to the usual practice in Spain, the individual stations and all associated lands should have been converted from monasteries into dioceses within about ten years. So it had already been completed at the other mission stations in Mexico, Central America and Peru. But Serra soon realized that he would need much longer on this northern border to win the indigenous population for the new faith and to set up the stations. The stations included extensive estates and herds of cattle, the locals were trained to care for and raise, which led to the formation of small villages around the stations. By 1800, the work of the Indians became the backbone of the Camino Real economy. None of the mission stations ever achieved complete financial independence, so that a certain (albeit small) support from Spain was always required. After the outbreak of the Mexican War of Independence , these payments were not made for understandable reasons and the stations were left to their own devices.

The epidemics brought in by European immigrants , particularly measles , caused considerable problems . While the Europeans were largely immune to these diseases, the Indian immune system had nothing to counter them. During the great epidemic of 1806, a third of Indians died of measles or related complications.

In 1812 the Russians reached Fort Ross in what is now Sonoma County as they advanced into California . That was the southernmost point of the Russian colonization attempts. In November and December 1818, several of the missions of Hippolyte de Bouchart , also known as "California's only pirate", were ambushed, partially looted or destroyed. While he got the reputation of a patriot in the countries of South America, he was considered a pirate in California . Many priests fled to the Nuestra Señora de la Soledad Mission because it was the best protected. Ironically, the Santa Cruz mission, which was spared the pirate raids, was particularly stolen by the residents who had been entrusted with protecting the church's treasures.

In 1819, because of the cost of maintaining these far-flung areas, Spain decided to limit its expansion in the New World to Upper California . A trip from Europe to California took about half a year until the middle of the 19th century, which made administration extremely difficult. The Sonoma Mission (founded in 1823) became the northernmost of the Spanish missions in California. The mission, however, was primarily a military base rather than a religious center - first against the Russians, then against the Americans. Nevertheless, a large church was built and Indians were baptized. The plan to establish another mission in Santa Rosa in 1827 was abandoned. At that time, the fear of the Russians was largely gone and the Americans remained the greatest threat. However, these were by no means the only countries claiming the area; China, India, Japan, Portugal and Holland also sought colonial possession. The French were for a long time the greatest threat to the Spaniards, but this was averted in 1763 by the defeat in the Seven Years' War and the associated withdrawal from America.

When the Republic of Mexico was proclaimed in 1824, calls for the secularization of the missions became louder. José María de Echeandía , the first Mexican governor of Alta California issued the so-called Prevenciónes de Emancipacion , "Proclamation of Emancipation" on July 25, 1826. This freed all qualified Indians in the military districts of San Diego, Santa Barbara and Monterey from the jurisdiction of the Missions and offered them Mexican citizenship. Corporal punishment was now largely prohibited for those who wanted to stay. Echeandía wanted to favor a few prominent Californians who had already cast their eyes on the lands of the mission stations.

By 1830, the new converts were also confident enough to be able to lead the missions themselves. The fathers were not yet convinced of this. Further immigration increased pressure on local governments to usurp the mission properties and dispossess the ranched Indians in order to give the area to the immigrants. Racist and often completely fictitious claims served as a pretext for these actions. In 1827, the Mexican government decided to expel all Spaniards under the age of 60 from the Mexican territories. However, Echeandía himself intervened to prevent some of the deportations when it actually came to that.

Although Governor José Figuera , who had been in office since 1833, initially tried to keep the mission system in good condition, the Mexican parliament has now also passed an act for the secularization of the missions in California . The law also provided for the colonization of both Alta and Baja California, the cost of which would be covered by the proceeds from sales of missionary property.

Rancho Period (1834–1849)

The San Juan Capistrano Mission was the first to be dissolved under the new laws on August 9, 1834. Nine more followed that same year and six in 1835. The last, including San Buenaventura and San Francisco, were secularized in June and December 1836. The Franciscans then gave up most of the missions, but took everything valuable with them. Subsequently, the mission stations were often plundered by the locals and used as a quarry for their own houses. Some of the missions, including San Juan Capistrano , San Dieguito and Las Flores Estancia , remained, however, as a clause in Echeandía's proclamation allowed the conversion to pueblos , i.e. villages. One estimate indicates that at the time of the confiscations alone the mission stations had 80,000 inhabitants, while other sources indicate that the population of the entire state had fallen to around 100,000 by 1840 - among other things because of the diseases already mentioned and because of the practice of the Franciscans, to put many women in the monastery or to restrict the offspring through birth control. In addition, however, the change in diet and the culture shock with the strong physical and psychological violence that the white immigrants used - especially during the subsequent gold rush - caused high death rates.

Pío Pico , the last Mexican governor of Alta California, discovered when he took office that the money to administer his province was scarce. He applied to parliament to let or sell the lands and farms belonging to the missions. The churches and the houses of the priests were not sold. It was hoped that the money raised would be able to finance the mission centers, but this only partially succeeded. After the secularization, the headquarters of the Franciscan Missions of Padre Presidente - that was the title of the head of the mission stations - Narciso Durán was moved to Santa Barbara. All essential writings about that time were also taken away, so that around 3,000 original writings from the earliest settlement period in California are kept in the Santa Barbara Mission. The library now serves important historical studies. The Santa Barbara Mission is the only one that has been continuously inhabited and managed by Franciscans since then.

Later, the secularization and the changes that went with it were heavily criticized in some cases. The lands were sold too cheaply or for profane purposes and the baptized Indians were scattered in the countryside and exposed to hunger.

“Disestablishment - a polite term for robbery - by Mexico (rather than by native Californians misrepresenting the Mexican government) in 1834, which was the death blow of the mission system. The lands were confiscated; the buildings were sold for beggarly sums, and often for beggarly purposes. The Indian converts were scattered and starved out; the noble buildings were pillaged for their tiles and adobes ... "

After the founding of the state

With the confiscation of the mission stations between 1834 and 1838, the approximately 15,000 neophytes lost the protection of the missions, along with their herds and all other movable property. With the formation of the US state of California, they also lost their right to land.

In May 1846, American settlers declared California's independence, and in September 1850 California became the thirty-first state as a result of the Mexican-American War . The Washington Congress passed a law on September 30, 1850, which allowed the President to negotiate treaties with various Indian tribes. By 1852 such contracts had been concluded with 402 Indian chiefs - these represented about a third to half of the Indians in California. As early as 1851, at the request of the Californian Senator William M. Gwin, the so-called " Public Land Commission " was set up to investigate the claims of the Mexican and Spanish settlers on the land in the following years. This had meanwhile been occupied in many places by the gold prospectors who had immigrated en masse during the gold rush . However, the conditions for being able to assert the claims were extremely high and the procedures very time-consuming and costly, so that many claimants either no longer experienced the return or were unable to pay the court costs to the end.

The Church was relatively successful in these processes. Archbishop Joseph Sadoc Alemany gave the missions back a large part of their lands. In 1875 some Indian reservations were also declared. The number of " missionary Indians " had fallen to around 3,000 by 1879, according to a commissioner.

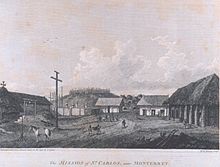

Structure and architecture of the missions

In addition to the presidios (forts) and the pueblos (villages), the misiónes were the third instrument with which the Spaniards expanded their borders and administered their colonies. The missions included Asistencias , small religious centers, outside of the missions, in which mass was occasionally held but where no priests of their own lived. Such asistencias were also established where there was a good chance of converting many Indians to Christianity. The mission stations had to be designed for self-sufficiency, since the procurement of supplies was not possible in a useful time at that time. The next colonial bases in Mexico were several months away from California and the ships of that time had only a small transport capacity. Therefore the monks had to rely on the help of immigrants or converted Indians.

When starting a new mission, there was a lot of bureaucracy that took months, sometimes years. Once the construction site was determined, simple huts were built for the missionaries and soldiers. The place had to be supplied with water, provide enough wood as building material and for fire, and provide space for livestock to graze. First, the location of the church, the mission's most important building, was determined. The houses of the priests, soldiers and servants, the refectory , workshops, the kitchen, warehouses and other buildings were mostly laid out around the patio . This was mostly laid out roughly square and was also used for festivities and ceremonies. In the event of danger, it also served as a retreat. A massive wall was erected on the outside and a covered colonnade was built on the inside. A bell tower or a wall of bells was always part of the mission.

The lack of imported building materials and the lack of skilled construction workers significantly influenced the architecture of the mission centers. Furthermore, the architecture was significantly influenced by the Spanish architecture of the time. The missionaries also lacked measuring instruments, which is why the layout of the facilities is often not arranged in an exact square. The buildings consist mainly of only five building materials: mud bricks , ceramic tiles , wood, stones and bricks . These were obtained near the construction sites. Lumber from large trees was relatively rare in the area, so that some of this had to be brought in from far away, which explains the often very small dimensions of the rooms. Stone was used wherever possible. However, due to a lack of knowledge, sandstone was used, which is easier to work with than other building materials but also less durable. Mud and dirt served as the mortar, as there was no lime available.

Brick bricks, in contrast to mud bricks, are burned , which gives them a significantly longer lifespan. Most of the fired brick buildings stood long after those made of mud bricks had turned to rubble.

The houses were initially covered with straw . After around 1790, bricks were also used. In addition to the obvious advantage of lower fire risk, these also resulted in an improvement in the service life of the walls, as they held tight and did not become damp inside.

Life in the missions

The main task of the missionaries was clear: to turn the Indians from their "free, undisciplined" life into civilized members of the community. A total of 146 Franciscans , all priests and most of them born in Spain, served in the missions in California between 1769 and 1845. 67 missionaries were killed, two of them, Luís Jayme and Andrés Quintana , as martyrs . At least Quintana was not insignificantly involved in his fate. Allegedly he tried to use scourges with steel ends against "his" workers. According to the rules of the Franciscan order, two priests lived in each mission and formed the convent . They were assigned five to six soldiers under the direction of a corporal. He was the overseer of the worldly affairs of the missions, based on the instructions of the Fathers.

Life in the various stations differed slightly, but many things were very similar everywhere. After an Indian was baptized , he became a neophyte . During this time, the baptized were taught the basics of Christianity and the Christian faith. Often the Indians were lured to a baptism out of pure curiosity or out of the conviction to participate in the trade. Many found, however, that through baptism they had committed themselves and their freedom to the missionaries. For the fathers, a baptized Indian was no longer free to move around the country, but had to do his work under the strict supervision of the brothers and overseers in the mission. The priests drove them to daily mass and work. Indians who did not report to work for a few days were wanted and, if they were caught, punished. In 1806, 20,355 Indians joined the missions, the highest number during the missionary period. This was exceeded again in 1824 with 21,066.

The young Indian women had to live in the so-called monjerío (women's monastery), where they were supervised and trained by a trustworthy Indian guide. They were only allowed to leave the convent when they had been "won" by an Indian and were ready for the wedding . Before the wedding, the potential partners were only allowed to get to know each other through a barred window, according to a Spanish custom. After the wedding, the woman moved from the mission quarters to one of the huts provided for families. These "women's monasteries" were seen by the priests as a necessity, as women had to be protected from men. The cramped conditions and precarious sanitary conditions led to the rapid spread of diseases and to a considerably increased mortality among women. This led to the fact that the Indian men asked the priests to conquer and subjugate further villages in order to obtain women for them. By December 31, 1832, the peak of the development of the missions, the priests had performed a total of 87,787 baptisms, held 24,529 weddings and registered 63,793 deaths.

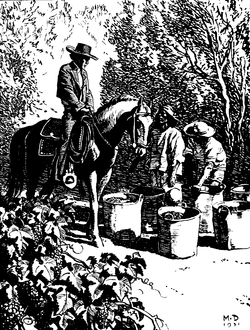

Bells played an essential role in the daily life of the missions. They were rung to call people to dinner and worship and to encourage them to work. Bells were also rung at births and funerals. The novices were told exactly when they had to ring which bells. The daily routine began at sunrise with early mass and prayer, followed by lessons in the Roman Catholic faith . After a generous breakfast from Atole - according to the standard at the time - the daily tasks were assigned. Tailoring, knitting, weaving, embroidery, washing and cooking were the main jobs of the women. Stronger women had to grind flour or carry clay bricks (weighing 25 kg) to the construction sites. The men's tasks were varied: the missionaries taught them plowing, sowing, irrigation, tending and harvesting in the fields. They also learned how to build houses from adobe bricks, tanning leather, shearing sheep, processing wool, the art of rope making, painting and other crafts.

The working day lasted six hours, interrupted by lunch at around 11:00 a.m. and a two-hour siesta . It was concluded with evening prayer, the rosary , dinner, and social activities. There were around 90 festival days each year to celebrate religious or civil festivals, these were non-working days. Despite this very progressive division of labor, even from today's perspective, the missions were a kind of slave camp. It was actually the intention of the Spanish missionaries to train and civilize the Indians and then to leave the mission and move on when it had become independent. But that didn't work because the missionaries tried to impose knowledge and a religion on the Indians that they could not understand. So the missionaries had no choice but to lead the Indians very strictly and precisely. Strangers visiting the missions reported the missionaries' excessive control of the Indians. Whether the hopelessly outnumbered whites and their isolation was hardly an alternative. No wages were paid to the Indians because they were not considered free workers. This enabled the missions to finance themselves and even generate a surplus. This was given to the (Spanish or European) settlers outside of the missions as support, who had more trouble economically, as they could not resort to "slave labor".

More recently there has been extensive debate about the actual treatment of Indians during the Spanish Missions in California. Many claim that the missions in California were directly responsible for the population decline among the locals. In particular, the intention of the Spanish Crown is also unclear. Were the missions really designed to spread the faith? Or just as a (disguised) border post? Did you want to promote conversion with the missions or did you want to protect the center of the colony in Mexico with the outposts and keep the Indians under control?

“The missionaries of California were by-and-large well-meaning, devoted men… [whose] attitudes toward the Indians ranged from genuine (if paternalistic) affection to wrathful disgust. They were ill-equipped — nor did most truly desire — to understand complex and radically different Native American customs. Using European standards, they condemned the Indians for living in a "wilderness," for worshiping false gods or no God at all, and for having no written laws, standing armies, forts, or churches. "

Agriculture and handicrafts in the mission stations

The missions should become self-sufficient in the shortest possible time. The most important industry in the missions was therefore agriculture . Among the cereals planted, barley , maize and wheat were the most important. The grain was dried and made into flour with stone mills . Even today, California is known for the great variety of fruit trees . The only "native" fruits in California were wild berries on bushes. The Spaniards had brought many seeds from Europe to California, which in turn had been imported from Asia to Europe. These included oranges , grapes , apples , peaches and a few more. The grapes were also pressed and fermented to make the wine needed for Holy Mass . Wine was also important for trade. The first grapes of the "Mission" variety (originating from the Criolla grande ) were planted in San Juan Capistrano in 1779. In 1783 it became the first wine to be produced in Alta California.

The San Gabriel Arcángel Mission unconsciously became the origin of the very important citrus industry in California today . The first significant citrus plantations were established here in 1804. However, their commercial potential was not discovered until 1841. Olives were first grown in the San Diego de Alcalá Mission. The coveted olive oil was extracted from it using large stone wheels . Father Serra also planted tobacco plantations in Carmel in 1774 , which was soon taken over to other mission stations. This was received very positively by the locals. They had urged Serra to give them Spanish tobacco.

It was also the mission of the missions to supply the Spanish forts (or presidios ) with food and handicrafts so that they could do their job. There was constant disagreement between the missions and the soldiers about the amount of grain, clothing, or fabric they each had to deliver. At times the missions were barely able to deliver the required quantities, especially when the harvest was poor due to drought or when shipments from overseas did not arrive. The amount of goods delivered was meticulously documented and sent to the Father-Presidente every year.

Cattle breeding also played an essential role in the missions. In 1832, at the height of the missions, the livestock of all 21 stations was given as follows:

- 151,180 cattle ;

- 137,969 sheep ;

- 14,522 horses ;

- 1,575 mules or donkeys ;

- 1,711 goats and

- 1,164 pigs

All of these animals were originally brought from Mexico. It took many locals to tend the herds, which soon earned them a very good reputation as cattle keepers. Due to the suitable climate in California, the animals reproduced much faster than expected, which means that the pastures became larger and larger. But the breeding success also had a downside: The uncontrolled growth of the cattle herds put a considerable strain on the pasture land and the animals destroyed the Indians' fields and their own crops. The Spaniards recognized the problem and at times sent out groups to kill escaped or runaway cattle. The mission kitchens and bakeries prepared thousands of meals every day. In addition to the meat, the animals were also processed into raw materials. Candles, soap and grease were extracted from the sebum . The wool of the sheep was made into clothes and the skin of the animals into leather.

Furthermore, the professions worth mentioning also include carpenters and builders for the houses, as well as the workers at the kilns for the bricks and the carpenters for the interior fittings. Ceramic pots and dishes were also made in the workshops of the missions.

Before the missionary work by the Spaniards, only bones, shells, stones and wood were known to the Indians as building materials, tools and weapons (only in pottery had some Indian societies created works on a par with European art). The missionaries found that they first had to teach the Indians the sense of handicraft and industry, because from the point of view of the locals, work, especially for the men, was something degrading. As a result, the missionaries established schools in which knowledge about agriculture, handicrafts and livestock was taught. This worked quite well under the supervision of the missionaries, and after 1811 the mission stations were not only self-sufficient but also the backbone of all military and civil life in California. The foundry in San Juan Capistrano was the first of its kind in California and brought the Iron Age (in Europe between about 1200 BC and 450 BC) to the New World. The iron obtained became an important commercial product and was central to the armament of the Spanish forts.

No description of the missions would be complete without mentioning the very extensive irrigation systems. So-called zanjas ( aqueducts ) made of stones led the water sometimes over miles from a river or a spring to the stations. Large cisterns were built into which the water was fed via a complex pipe system. The water was also used as an energy source, for example in mills. The water was filtered through coal and sand for drinking water treatment .

The missions in present-day California (USA)

founding

Before 1754, the Spanish Crown was responsible for granting land donations. But because of the great distances and the difficult lines of communication, the task and power to forgive land was entrusted to the viceroys of New Spain. New missions with the associated land could thus arise more quickly. The 21 missions were built along the Camino Real, the “Royal Route”, which was named in honor of King Charles III. Today it is mostly US Route 101. The first mission was established in 1767 by Father Junípero Serra, OFM, who had previously received control of the missions in Baja California led by the Jesuits up until then with some of his confreres .

In 1784, Father Pedro Estévan Tápis pursued a plan to establish a mission in the Channel Islands of California . Santa Catalina Island or Santa Cruz Island (known as Limú by the indigenous population) were favored as a possible location to proselytize the indigenous people who do not live on the mainland. In order to curb the smuggling trade, a location on an offshore island was also considered by the missionaries. In the following year, Governor José Joaquín de Arrillaga was also inclined to the plan, but the outbreak of an epidemic ( measles ), which fell victim to around 200 indigenous people, and the lack of arable land and the necessary water on the Channel Islands made it impossible to establish itself a mission. In September 1821, Father Mariano Payeras visited the missions of California in his capacity as " Comisario Prefecto " and visited Cañada de Santa Ysabel . He drew up a plan for a chain of missions on the mainland. Santa Ysabel should serve as the "central" mission of California. But this plan was not implemented either.

Even if Junípero Serra died in 1784, the establishment of the missions did not end until 1823. Further plans that existed for the establishment of missions were abandoned. For example, the establishment of the Santa Rosa Mission in 1827, since the risk of Russian penetration on the Pacific coast was no longer classified as relevant. At the height of the missions in Alta California, they controlled about 1/6 of the area. Two settlements, Mission Puerto de Purísima Concepción and Mission San Pedro y San Pablo de Bicuñer , which were founded on the California side of the Colorado River , were under the authority of the missions in Arizona .

Maintenance & restoration of the missions

No other historical building structures have received such great interest in the United States. California has the highest number of restored missions in the USA and one reason for this is, among other things, the “young” history of the missions in California in contrast to Florida, for example. In the coastal region of California, the Missions are the best-studied archaeological and historical buildings. Some quirks are listed below:

- all missions are owned by the Catholic Church , with the exception of the La Purísima Concepción Mission and the San Francisco Solano Mission, which are maintained as State Historic Parks by the California Department of Parks and Recreation.

- Seven missions are National Historic Landmarks , fourteen missions are listed on the National Register of Historic Places , and all missions are listed as California Historical Landmarks because of their historical, architectural, and archaeological significance .

- Four missions are directed under the direct leadership of the Franciscans : San Antonio de Padua, Santa Barbara, San Miguel Arcángel, and San Luis Rey de Francia.

- Four missions (San Diego de Alcalá, San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo, San Francisco de Asís, and San Juan Capistrano ) were elevated to the status of Basilicae Minores by the Holy See for their cultural, historical, architectural and archaeological importance.

Due to the artistic equipment of the missions, be it in the devotional and / or didactic area, there was no reason for the "mission residents" to depict their surroundings in pictures. But visitors to the missions found them strange. During the 1850s, a number of artists found employment as draftsmen and constructors needed for expeditions to explore the Pacific coast and the California-Mexico border. In this context, a large number of lithographs of the missions were created, which were recorded in the expedition records.

The American illustrator Henry Chapman Ford visited each of the 21 missions in 1875 and developed a collection of portfolios of water and oil paints and etchings that is historically relevant to this day. His descriptions of the missions were partly responsible for the fact that the public became more and more interested in the Spanish heritage, and thus also in a restoration of the missions. In the last quarter of the 19th century a large number of articles on the missions appeared in national journals as well as the first monographs. As a result, another large number of paintings etc. appeared again.

An increasing popularity and romanticization of the missions and mission history goes back to Helen Hunt Jackson 's novella Ramona from 1884. Even Charles Fletcher Lummis , William Randolph Hearst , and other members of the "Landmarks Club of Southern California," which were aimed to restore three of the southern missions at the beginning of the 20th century, were influential. San Juan Capistrano, San Diego de Alcalá, and San Fernando; the Pala Asistencia was also restored in the process. In this context, Lummis wrote in 1885:

In ten years from now — unless our intelligence shall awaken at once — there will remain of these noble piles nothing but a few indeterminable heaps of adobe. We shall deserve and shall have the contempt of all thoughtful people if we suffer our noble missions to fall.

Knowing that enormous efforts would have to be made immediately to prevent further destruction of the missions, Lummis continues:

It is no exaggeration to say that human power could not have restored these four missions had there been a five year delay in the attempt.

In his 1911 three-hour play The Mission Play, author John S. McGroarty points to the final destruction in 1847 (the play describes the California missions from their founding in 1769 to secularization in 1834).

Today the missions have been restored in their integrity and structure in various forms. In general, the mission site, along with the church and the convento ( convent ) has been preserved. In some cases (for example, San Rafael, Santa Cruz, and Soledad) these are replicas of buildings that were rebuilt at or near the historic site. Other missions have remained relatively intact and have been left in the original location.

A remarkable example of an intact mission complex is the now threatened San Miguel Arcángel Mission: the interior walls of the chapel, which were artistically worked out by the Salinan , an indigenous group under the supervision of the last Spanish diplomat Esteban Munras , have been in existence since 2003 no longer accessible to the public (the reason for this is the earthquake of 2003 ). Many missions were restored and even rebuilt in connection with their chapels.

The missions in California have become part of the historical “awareness” and interest that can be seen in the many tourists who visit the missions every year. For this reason, President George W. Bush signed the "California Mission Preservation Act" on November 30, 2004, which gave it the character of a law. Over a five-year period, the California Missions Foundation received $ 10 million under this law to secure the physical restoration, security, and conservation of the mission buildings and works of art for the future. There has also been an attempt to amend the California constitution so that state funds could be used for the restoration.

El Camino Real

In order to ensure and facilitate rapid communication, among other things, the missions were set up around 48 kilometers from each other. This distance corresponded to a day's ride or a three-day walk. Overall, El Camino Real ("the royal road"), on which the missions are located, has a length of about 966 kilometers. Father Lasuén is considered to be the “idea generator” of this concept when he advocated the establishment of “path stations” in 1798, so that travelers could find a relatively safe and comfortable resting place. The priests use yellow plants to mark the road. The transport of heavy goods and "bulk goods" took place by sea.

Geographical location of the missions (from north to south)

- Mission San Francisco Solano , in Sonoma

- Mission San Rafael Arcángel , in San Rafael

- Mission San Francisco de Asís (Mission Dolores), in San Francisco

- Mission San José , in Fremont

- Mission Santa Clara de Asís , in Santa Clara

- Mission Santa Cruz , in Santa Cruz

- Mission San Juan Bautista , in San Juan Bautista

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo , south of Carmel

- Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad , south of Soledad

- Mission San Antonio de Padua , northwest of Jolon

- Mission San Miguel Arcángel , in San Miguel

- Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa , in San Luis Obispo

- Mission La Purísima Concepción , northeast of Lompoc

- Mission Santa Inés , in Solvang

- Santa Barbara Mission , in Santa Barbara

- Mission San Buenaventura , in Ventura

- Mission San Fernando Rey de España , in Mission Hills

- Mission San Gabriel Arcángel , in San Gabriel

- Mission San Juan Capistrano , in San Juan Capistrano

- Mission San Luis Rey de Francia , in Oceanside

- Mission San Diego de Alcalá , in San Diego

The founding dates of the Alta California missions

- Mission San Diego de Alcalá founded in 1769

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo founded in 1770

- Mission San Antonio de Padua founded in 1771

- Mission San Gabriel Arcángel founded in 1771

- Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa founded in 1772

- Mission San Francisco de Asís (Mission Dolores) founded in 1776

- Mission San Juan Capistrano founded in 1776

- Mission Santa Clara de Asís founded in 1777

- Mission San Buenaventura founded in 1782

- Mission Santa Barbara founded in 1786

- Mission La Purísima Concepción founded in 1787

- Mission Santa Cruz founded in 1791

- Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad founded in 1791

- Mission San José founded in 1797

- Mission San Juan Bautista founded in 1797

- Mission San Miguel Arcángel founded in 1797

- Mission San Fernando Rey de España founded in 1797

- Mission San Luis Rey de Francia founded in 1798

- Mission Santa Inés founded in 1804

- Mission San Rafael Arcángel founded in 1817 - originally planned as an asistencia for the Mission San Francisco de Asís

- Mission San Francisco Solano founded in 1823 - originally planned as an asistencia for the Mission San Rafael Arcángel

The Asistencias (geographically from north to south)

- San Pedro y San Pablo Asistencia , founded in Pacifica in 1786

- Santa Margarita de Cortona Asistencia , founded in 1787 in Santa Margarita

- Nuestra Señora Reina de los Angeles Asistencia , founded in Los Angeles in 1784

- Santa Ysabel Asistencia , founded in Santa Ysabel in 1818

- San Antonio de Pala Asistencia (Pala Mission), founded in 1816 in eastern San Diego County

The estancias (geographically from north to south)

- San Bernardino de Sena Estancia , founded in Redlands in 1819

- Santa Ana Estancia , founded in Costa Mesa in 1817

- Las Flores Estancia (Las Flores Asistencia), founded in Camp Pendleton in 1823

Headquarters of the missions in Alta California

- Mission San Diego de Alcalá (1769–1771)

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo (1771-1815)

- Mission La Purísima Concepción * (1815–1819)

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo (1819-1824)

- Mission San José * (1824-1827)

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo (1827-1830)

- Mission San José * (1830–1833)

- Santa Barbara Mission (1833–1846)

* Father Payeras and Father Narcisco Durán remained in their respective missions as chief administrators of the Alta Californias missions, so that these are de facto the main administrative headquarters. It was not until 1833 that the Santa Barbara Mission was appointed as the main administrative seat to which all mission documents were brought.

Order Chair of the Missions in Alta California

- Father Junípero Serra (1769–1784)

- Father Francisco Palóu ( Chairman pro tempore ) (1784–1785)

- Father Fermín Francisco de Lasuén (1785–1803)

- Father Pedro Estévan Tápis (1803-1812)

- Father José Francisco de Paula Señan (1812–1815)

- Father Mariano Payéras (1815-1820)

- Father José Francisco de Paula Señan (1820–1823)

- Father Vicente Francisco de Sarría (1823-1824)

- Father Narciso Durán (1824-1827)

- Father José Bernardo Sánchez (1827–1831)

- Father Narciso Durán (1831–1838)

- Father José Joaquin Jimeno (1838–1844)

- Father Narciso Durán (1844–1846)

The title of "Padre Presidente" was the chairman of all Catholic missions in California. He was appointed to the College of San Fernando de Mexico until 1812 . Afterwards he was called “Prefecto Comisario” (“Leading Prefect”) and he was appointed by the responsible Franciscan commissioner in Spain. After 1831, two different people were appointed for Upper California and Lower California.

The military up to the annexation of Alta California by the USA

During the Spanish colonial period and the subsequent affiliation to Mexico, four presidios strategically located on the California coast took over the protection of the missions and civilian settlements in Alta California. Each of the garrisons ( comandancias ) served as the base for the respective military operations in a particular area. Although the Presidios operated relatively independently of one another, there was a constant connection between the Presidios solely through the missions and their communication channels. The following presidios existed:

- El Presidio Real de San Diego , founded July 16, 1769 - responsible for protecting the San Diego de Alcalá, San Luis Rey, San Juan Capistrano, and San Gabriel missions

- El Presidio Real de Santa Bárbara , founded on April 12, 1782 - responsible for the protection of the missions San Fernando, San Buenaventura, Santa Barbara, Santa Inés and La Purísima, and the civilian settlement of El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles del Río de Porciúncula

- El Presidio Real de San Carlos de Monterey ( El Castillo ), founded on June 3, 1770 - responsible for the protection of the San Luis Obispo, San Miguel, San Antonio, Soledad, San Carlos, and San Juan Bautista missions and the civilian settlement of Villa Branciforte [Santa Cruz] ;

- El Presidio Real de San Francisco , founded on December 17, 1776. - responsible for the protection of the missions San José, Santa Clara, San Francisco, San Rafael, Solano and the civilian settlement of El Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe [San Jose] .

The El Presidio de Sonoma , or the "Sonoma Barracks" ("Barracks of Sonoma") was only founded after Mexico's independence from Spain in 1836 by Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo (the "Commandante-General of the northern border of Alta California"). This foundation was based on the Mexican strategy to prevent further Russian penetration on the California coast. The Sonoma Presidio was expanded to become the headquarters of the Mexican Army in California, while the other presidios were abandoned and fell into disrepair over time.

For decades there were disputes over competence between the military on the one hand and the missionaries on the other. The origin of these disputes can be traced back to Junipero Serra and Pedro Fages , who was governor of Alta California from 1770 to 1774. Pedro Fages saw the Presidios and the associated garrisons as a purely military institution that should serve to protect California from other European powers, and not like Serra that they should submit to the missionaries. Despite all the disputes, there was a mutual dependence: the missions provided food and the garrisons in return protection and were responsible for punitive expeditions against volatile neophytes. The soldiers were needed primarily to carry out punishments. Nevertheless, Engelhardt describes impressively that it was precisely the soldiers whose personal social background did not agree with the mission statement.

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ Saunders & Chase, p. 65.

- ↑ Today Franciscans mostly wear brown cassocks ; Kelsey, p. 18.

- ↑ Leffingwell, p. 10: " Antonio de la Ascensión surveyed the area and concluded that the land was fertile, the fish plentiful, and gold abundant ."

- ^ Morrison, p. 214.

- ↑ Rawls, p. 6.

- ↑ Kroeber 1925, p. VI .: " In the matter of population, too, the effect of Caucasian contact cannot be wholly slighted, since all statistics date from a late period. The disintegration of native numbers and native culture have proceeded hand in hand, but in very different rations according to locality. The determination of populational strength before the arrival of whites is, on the other hand, of considerable significance toward the understanding of Indian culture, on account of the close relations which are manifest between type of culture and density of population . "

- ↑ Chapman, p. 383: “ … there may have been about 133,000 [native inhabitants] in what is now the state as a whole, and 70,000 in or near the conquered area. The missions included only the Indians of given localities, though it is true that they were situated on the best lands and in the most populous centers. Even in the vicinity of the missions, there were some unconverted groups, however . "

- ↑ Engelhardt 1922, p. 258.

- ↑ Leffingwell, p. 25.

- ↑ Engelhardt 1922, p. 258: Today the site (at 33 ° 25 '41.58 "N, 177 ° 36' 34.92" W at Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton in San Diego County ) is more generally called La Cañada de los Bautismos , literally “The Gorge of Baptisms ”or simply Los Christianitos “ the little Christians ”and is a California Historical Landmark # 562 .

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, p. 76.

- ↑ d. H. should be handed over to non-religious clergy, cf. Clergy .

- ↑ Robinson, p. 28.

- ↑ a b c Engelhardt 1908, pages 3-18: “ [They created the need for]… a class of horsemen scarcely surpassed anywhere. "

- ↑ Bennett 1897a, p. 13.

- ↑ Milliken, pp. 172f. u. 193.

- ↑ Kelsey, p. 4.

- ↑ Nordlander, p. 10.

- ↑ Young, p. 102.

- ↑ Hittell, p. 499: “… it [Mission San Francisco Solano] was quite frequently known as the mission of Sonoma. From the beginning it was rather a military than a religious establishment — a sort of outpost or barrier, first against the Russians and afterwards against the Americans; but still a large adobe church was built and Indians were baptized. "

- ↑ Hittell, p. 499: “By that time, it was found that the Russians were not such undesirable neighbors as in 1817 it was thought they might become… the Russian scare, for the time being at least was over; and as for the old enthusiasm for new spiritual conquests, there was none left. "

- ↑ Bennett 1897b, p. 154: “Up to 1817 the 'spiritual conquest' of California had been confined to the territory south of San Francisco bay. And this, it might be said, was as far as possible under the mission system. There had been a few years prior to that time certain alarming incursions of the Russians, which distressed Spain, and it was ordered that missions be started across the bay . "

- ↑ Chapman, pp. 254-255: “… the Russians and the English were by no means the only foreign peoples who threatened Spain's domination of the Pacific coast. The Indians and the Chinese had their opportunity before Spain appeared upon the scene. The Japanese were at one time a potential peril, and the Portuguese and Dutch voyagers occasionally gave Spain concern. The French for many years were the most dangerous enemy of all, but with their disappearance from North America in 1763, as a result of their defeat in the Seven Years' War, they were no longer a menace. The people of the United States were eventually to become the most powerful outstanding element. "

- ↑ Robinson, p. 29: The Spanish cortes , or legislature, issued a decree in 1813 for at least partial secularization affecting all missions in America that was to apply to all outposts which had been operating for ten years or more; however, the decree was never enforced in California.

- ↑ Engelhardt 1922, p. 80.

- ↑ Bancroft, vol. i, pp. 100-101: The motives behind the issuance of Echeandía's premature decree had more to do with the his desire to appease " ... some prominent Californians who had already had their eyes on the mission lands ... " than they did with concerns regarding the welfare of the natives.

- ↑ Stern and Miller, pp. 51–52: Catholic historian Zephyrin Engelhardt referred to Echeandía as " ... an avowed enemy of the religious orders ."

- ↑ Forbes, p. 201: In 1831, the number of Indians under missionary control in all of Upper California stood at 18,683; garrison soldiers, free settlers, and "other classes" totaled 4,342.

- ↑ Kelsey, p. 21: Settlers made numerous false claims in order to diminish the natives' stature: " The Indians are by nature slovenly and indolent ," stated one newcomer. " They have unfeelingly appropriated the region ," claimed another.

- ↑ Engelhard 1922, p. 223.

- ↑ Yenne, pp. 18-19.

- ↑ Engelhardt 1922, p. 114

- ↑ Yenne, p. 83 and P. 93.

- ↑ Robinson, p. 42.

- ↑ Cook, p. 200: When assessing the relative importance of the various sources of the native population decline in California, including Old World epidemic diseases, violence, nutritional changes, and cultural shock, it is clear that declines tended to be steepest in the areas directly affected by the missions and the Gold Rush . " The first (factor) was the food supply ... The second factor was disease ... A third factor, which strongly intensified the effect of the other two, was the social and physical disruption visited upon the Indian. He was driven from his home by the thousands, starved, beaten, raped, and murdered with impunity. He was not only given no assistance in the struggle against foreign diseases, but was prevented from adopting even the most elementary measures to secure his food, clothing, and shelter. The utter devastation caused by the white man was literally incredible, and not until the population figures are examined does the extent of the havoc become evident . "

- ↑ James, p. 215.

- ↑ Engelhardt 1922, p. 248.

- ↑ Robinson, p. 14.

- ↑ Robinson, pp. 31-32: The area shown is that stated in the Corrected Reports of Spanish and Mexican Grants in California Complete to February 25, 1886 as a supplement to the Official Report of 1883-1884. Patents for each mission were issued to Archbishop Joseph Sadoc Alemany based on his claim filed with the Public Land Commission on February 19, 1853.

- ↑ Rawls, pp. 112-113.

- ^ Newcomb, Rexford: The Franciscan Mission Architecture of Alta California . Dover Publications, Inc., New York, NY, 1973, ISBN 0-486-21740-X , p. 15.

- ↑ Harley

- ↑ Ruscin, p. 61.

- ^ Johnson, P., ed .: The California Missions . Lane Book Company, Menlo Park, CA, 1964.

- ↑ Ruscin, p. 12.

- ↑ Paddison, page 48th

- ↑ Chapman, pp. 310-311: “ Latter-day historians have been altogether too prone to regard the hostility to the Spaniards on the part of the California Indians as a matter of small consequence, since no disaster in fact ever happened… On the other hand the San Diego plot involved untold thousands of Indians, being virtually a national uprising, and owing to the distance from New Spain to and the extreme difficulty of maintaining communications a victory for the Indians would have ended Spanish settlement in Alta California . "As it turned out, " ... the position of the Spaniards was strengthened by the San Diego outbreak, for the Indians felt from that time forth that it was impossible to throw out their conquerors ." See also Quechan .

- ↑ Engelhardt 1922, p. 12: Not all Indian peoples were hostile to the Spaniards; Engelhardt portrayed the Indians in the San Juan Capistrano Mission, where there was never a corresponding uproar, but wrote that they were unusually peaceful and docile / docile . Father Juan Crespí , who accompanied the expedition in 1769, described the first encounter with the local residents as follows: “ They came unarmed and with a gentleness which has no name they brought their poor seeds to us as gifts… The locality itself and the docility of the Indians invited the establishment of a mission for them . "

- ↑ Rawls, pp. 14-16.

- ^ Leffingwell, Randy: California Missions and Presidios: The History & Beauty of the Spanish Missions . Voyageur Press, Inc., Stillwater, MN, 2005, ISBN 0-89658-492-5 , p. 132.

- ↑ Chapman, p. 383: “ Over the hills of the Coast Range, in the valleys of the Sacramento and San Joaquin , north of San Francisco Bay , and in the Sierra Nevadas of the south there were untold thousands whom the mission system never reached ... they were as if in a world apart from the narrow strip of coast which was all there was of the Spanish California . "

- ↑ Paddison, p 130

- ^ Newcomb, pp. Viii.

- ^ Krell, p. 316.

- ↑ Engelhardt 1922, p. 30.

- ↑ Bennett 1897b, p. 156: “ The system had singularly failed in its purposes. It was the design of the Spanish government to have the missions educate, elevate, civilize, the Indians into citizens. When this was done, citizenship should be extended them and the missions should be dissolved as having served their purpose ... [instead] the priests returned them projects of conversion, schemes of faith, which they never comprehended ... He [the Indian] became a slave ; the mission was a plantation; the friar was a taskmaster . "

- ↑ Bennett 1897b, p. 158: " In 1825 Governor Argüello wrote that the slavery of the Indians at the missions was bestial ... Governor Figueroa declared that the missions were 'entrenchments of monastic despotism' ... "

- ↑ Bennett 1897b, p. 160: " The fathers claimed all the land in California in trust for the Indians, yet the Indians received no visible benefit from the trust ."

- ↑ Bennett 1897b, p. 158: " It cannot be said that the mission system made the Indians more able to sustain themselves in civilization than it had found them ... Upon the whole it may be said that this mission experiment was a failure ."

- ↑ Lippy, p. 47: “ A matter of debate in reflecting on the role of Spanish missions concerns the degree to which the Spanish colonial regimes regarded the work of the priests as a legitimate religious enterprise and the degree to which it was viewed as a 'frontier institution,' part of a colonial defense program. That is, were Spanish motives based on a desire to promote conversion or on a desire to have religious missions serve as a buffer to protect the main colonial settlements and an aid in controlling the Indians? "

- ↑ Bennett 1897a, p. 10: The missions in effect served as “ … the citadels of the theocracy which was planted in California by Spain, under which its wild inhabitants were subjected, which stood as their guardians, civil and religious, and whose duty it was to elevate them and make them acceptable as citizens and Spanish subjects ... it remained for the Spanish priests to undertake to preserve the Indian and seek to make his existence compatible with higher civilization . "

- ↑ Paddison, p xiv

- ^ Thompson A., p. 341.

- ↑ Bean and Lawson, p. 37: " Serra's decision to plant tobacco at the missions was prompted by the fact that from San Diego to Monterey the natives invariably begged him for Spanish tobacco ."

- ^ Krell, p. 316: December 31, 1832.

- ↑ Engelhardt 1922, p. 211.

- ↑ Capron, p. 3.

- ↑ Bancroft, pp. 33-34.

- ↑ Hittell, p. 499: “ By that time, it was found that the Russians were not such undesireable neighbors as in 1817 it was thought they might become… the Russian scare, for the time being at least was over; and as for the old enthusiasm for new spiritual conquests, there was none left . "

- ^ Father Fermín Francisco de Lasuén took up Serra's work and established nine more mission sites, from 1786 through 1798; others established the last three compounds, along with at least five asistencias .

- ↑ Young, p. 17.

- ↑ Robinson, p. 25.

- ↑ Morrison, p. 214: That the buildings in the California mission chain are in large part intact is due in no small measure to their relatively recent construction; Mission San Diego de Alcalá was founded more than two centuries after the establishment of the Mission of Nombre de Dios in St. Augustine, Florida in 1565 and 170 years following the founding of Mission San Gabriel del Yunque in present-day Santa Fe, New Mexico in 1598.

- ↑ Listing of National Historic Landmarks by State: California. National Park Service , accessed August 3, 2019.

- ↑ Young, p. 18.

- ^ Stern & Miller, p. 85.

- ↑ Stern & Neuerburg, p. 95.

- ↑ Thompson, Mark, pp. 185–186: In the words of Charles Lummis, the historic structures " ... were falling to ruin with frightful rapidity, their roofs being breached or gone, the adobe walls melting under the winter rains ."

- ↑ "Past Campaigns"

- ↑ Stern & Miller, p. 60.

- ↑ California Missions Preservation Act (PDF; 143 kB)

- ↑ Coronado & Ignatin.

- ↑ Yenne, p. 132; Bennett 1897b, p. 152: “ With the ten missions first established, the occupation of Alta California may be said to have been completed… They were, however, at wide distances apart, and for the sake of mutual protection and accessibility, as well as for the better conducting of the work of spiritual subjugation of all the Indians, it was necessary that the intervening spaces be settled by additional missions. It was accordingly ordered by the Mexican viceroy, the Marquis de Branciforte , that five new missions should be established, to be placed on lines of travel as near as might be between the existing missions ... "

- ↑ Markham, p. 79; Riesenberg, p. 260.

- ↑ Yenne, pp. 18–19: In 1833 Figueroa replaced the padres at all of the settlements north of Mission San Antonio de Padua with Mexcian-born Franciscan priests from the College of Guadalupe de Zacatecas . In response, Father-Presidente Narciso Durán transferred the headquarters of the Alta California Mission System to Mission Santa Bárbara, where they remained until 1846.

- ^ Yenne, p. 186.

- ↑ Ruscin, p. 196.

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, p. 228.

- ↑ Leffingwell, p. 22.

- ↑ Forbes, p. 202: In 1831 the garrison consisted of 796 soldiers who were responsible for the protection and control of 6465 neophythes.

- ↑ Leffingwell, p. 68.

- ↑ Forbes, p. 202: In 1831 the garrison consisted of 613 soldiers who were responsible for the protection and control of 3292 neophythes. The number of residents of El Pueblo de los Ángeles consisted of 1388 people.

- ↑ Leffingwell, p. 119.

- ↑ Forbes, p. 202: In 1831 the garrison consisted of 708 soldiers who were responsible for the protection and control of 3305 neophythms. The number of Villa Branciforte consisted of 130 people.

- ↑ Leffingwell, p. 154.

- ↑ Forbes, p. 202: In 1831 the garrison consisted of 371 soldiers who were responsible for the protection and control of 5,433 neophytes. The number of El Pueblo de San José consisted of 524 people.

- ↑ Leffingwell, p. 170.

- ↑ Paddison, p. 23

- ↑ Bennett 1897a, p. 20: " ... Junípero had insisted in California that the military should be subservient to the priests, that the conquest was spiritual, not temporal ... "

- ↑ Engelhardt 1922, pp. 8-10: “ Recruited from the scum of society in Mexico, frequently convicts and jailbirds, it is not surprising that the mission guards, leather-jacket soldiers, as they were called, should be guilty of ... crimes at nearly all the missions… In truth, the guards counted among the worst obstacles to missionary progress. The wonder is that the missionaries nevertheless succeeded so well in attracting converts . "

literature

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe: History of California. Volume I-VII. (1801-1890) . San Francisco, CA: The History Company 1886-1890. [1]

- Bean, Lowell John & Harry Lawton (Eds.): Native Californians: A Theoretical Retrospective . Banning, CA: Ballena Press 1976.

- Bennett, John E .: Should the California Missions Be Preserved? Part I . In: Overland Monthly, vol. 29: 169 (1897a), pp. 9-24. [2]

- Bennett, John E .: Should the California Missions Be Preserved? - Part II . In: Overland Monthly, vol. 29: 170 (1897b), pp. 150-161. [3]

- Capron, Elisha Smith: History of California from its Discovery to the Present Time . Cleveland, OH: Jewett & Company 1854.

- Chapman, Charles E .: A History of California: The Spanish Period . New York: The MacMillan Company 1921. [4]

- Cook, Sherburne F .: The Population of the California Indians, 1769-1970 . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press 1976. ISBN 0-520-02923-2

- Coronado, Michael & Heather Ignatin: Plan would open Prop. 40 funds to missions . In: The Orange County Register (June 5, 2006), accessed October 5, 2009. [5]

- Crespí, Juan: A Description of Distant Roads: Original Journals of the First Expedition into California, 1796-1770 . San Diego, CA: SDSU Press 2001. ISBN 1-879691-64-7

- Engelhardt, Zephyrin, OFM: The Missions and Missionaries of California, Volume One . San Francisco, CA: The James H. Barry Co. 1908.

- Engelhardt, Zephyrin, OFM: San Diego Mission . San Francisco, CA: James H. Barry Company 1920.

- Engelhardt, Zephyrin, OFM: San Juan Capistrano Mission . Los Angeles, CA: Standard Printing Co. 1922.

- Forbes, Alexander: California: A History of Upper and Lower California. From their first discovery to the present time . New York: Arno Press 1973. ISBN 0-405-04972-2

- Geiger, Maynard J., OFM: Franciscan Missionaries in Hispanic California, 1769-1848: A Biographical Dictionary . San Marino, CA: Huntington Library 1969.

- Hittell, Theodore H .: History of California, Volume I . San Francisco, CA: Stone & Company 1898. [6]

- James, George Wharton: The Old Franciscan Missions of California . Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co. Inc. 1913. [7] [8]

- Jones, Terry L. & Kathryn A. Klar (Eds.): California Prehistory: Colonization, Culture, and Complexity . Landham, MD: Altimira Press 2007. ISBN 0-7591-0872-2

- Kelsey, H .: Mission San Juan Capistrano: A Pocket History . Altadena, CA: Interdisciplinary Research 1993. ISBN 0-9785881-0-X

- Krell, Dorothy (Ed.): The California Missions: A Pictorial History . Menlo Park, CA: Sunset Publishing Corporation 1979. ISBN 0-376-05172-8

- Kroeber, Alfred L .: A Mission Record of the California Indians . In: American Archeology and Ethnology, vol. 8: 1 (1908), pp. 1-27. [9]

- Kroeber, Alfred L .: Handbook of the Indians of California . Washington: Govt. Print. Off. 1925. (Reprint: 2 vol., Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Pub Co 2007. ISBN 1-4286-4492-X and ISBN 1-4286-4493-8 )

- Leffingwell, Randy: California Missions and Presidios: The History & Beauty of the Spanish Missions . Stillwater, MN: Voyageur Press 2005. ISBN 0-89658-492-5

- Markham, Edwin: California the Wonderful: Her Romantic History, Her Picturesque People, Her Wild Shores . New York: Hearst's International Library Company 1914.

- McKanna, Clare Vernon: Race and Homicide in Nineteenth-Century California . Reno, NV: University of Nevada Press 2002. ISBN 0-87417-515-1

- Milliken, Randall: A Time of Little Choice: The Disintegration of Tribal Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area 1769-1910 . Menlo Park, CA: Ballena Press 1995. ISBN 0-87919-132-5

- Moorhead, Max L .: The Presidio: Bastion of The Spanish Borderlands . Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press 1991. ISBN 0-8061-2317-6

- Morrison, Hugh: Early American Architecture: From the First Colonial Settlements to the National Period . New York: Dover Publications 1987. ISBN 0-486-25492-5

- Newcomb, Rexford: The Franciscan Mission Architecture of Alta California . New York: Dover Publications 1973. ISBN 0-486-21740-X

- Nordlander, David J .: For God & Tsar: A Brief History of Russian America 1741-1867 . Anchorage, AK: Alaska Natural History Association 1994. ISBN 0-930931-15-7

- Paddison, Joshua (Ed.): A World Transformed: Firsthand Accounts of California Before the Gold Rush . Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books 1999. ISBN 1-890771-13-9

- Rawls, James J .: Indians of California: The Changing Image . Norman, OK: Univ. of Oklahoma Press 1986. ISBN 0-8061-2020-7

- Rawls, James J .: California: An Interpretive History . 9th ed., New York: McGraw-Hill 2006. ISBN 0-07-353464-1

- Robinson, William W .: Land in California: the story of mission lands, ranchos, squatters, mining claims, railroad grants, land scrip, homesteads . Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press 1979. ISBN 0-520-03875-4

- Robinson, WW: Panorama: A Picture History of Southern California . Los Angeles, CA: Anderson, Ritchie & Simon 1953.

- Ruscin, Terry: Mission Memoirs: A Collection of Photographs, Sketches & Reflections of California's Past . San Diego, CA: Sunbelt Publications 1999. ISBN 0-932653-30-8

- Saunders, Charles Francis & J. Smeaton Chase: The California Padres and Their Missions . Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin 1915. (Reprint: Cambridge Scholars Publishing 2009. ISBN 0-217-32491-6 ) [10]

- Stern, Jean & Gerald J. Miller: Romance of the Bells: The California Missions in Art . Irvine, CA: The Irvine Museum 1995. ISBN 0-9635468-5-6

- Thompson, Mark: American Character: The Curious Life of Charles Fletcher Lummis and the Rediscovery of the Southwest . New York: Arcade Publishing 2001. ISBN 1-55970-550-7

- Yenne, Bill: The Missions of California . San Diego, CA .: Thunder Bay Press 2004. ISBN 1-59223-319-8

Web links

- California Historical Society

- California Mission Studies Association

- Web de Anza: Spanish Exploration and Colonization of "Alta California" 1774-1776

- California Missions in The Catholic Encyclopedia

- The Journal of San Diego History

- Matrimonial Investigation records of the San Gabriel Mission in Claremont Colleges Digital Library

- The San Diego Founders Trail , 2001-2008. Official website