Western calligraphy

Western calligraphy ( Greek κάλλος kállos "beauty" or καλός kalós "beautiful", "good" and graphics ) describes the calligraphy in Latin , Greek or Cyrillic letters and represents an independent art form. It had its heyday in the High Middle Ages , as a There was a high demand for Bible copies and is still practiced today as a relaxing hobby or on special occasions. In Europe and North America, calligraphy is mostly done with a ribbon nib, a pen with a broad tip.

The history of calligraphy is inextricably linked with the development of writing . Calligraphy does not only mean writing with a brush or pen , but also the artistic engraving of texts in wood, stone or metal. In the Middle Ages it flourished in Europe , which, in addition to the strong activity of Christian monasteries, was connected with the establishment of the first universities and the resulting need for books. With the advent of book printing, master scribes handed down the art of writing different font styles by hand. Nowadays the art of writing tends to lead a shadowy existence alongside the other art forms, but examples of excellent and innovative handwritten font design can always be found.

Tools and aids

Traditional writing implements

Described substances

In ancient times and well into the Middle Ages , papyrus was the measure of all things. Documents were recorded on it, manuscripts were written and religious texts immortalized. The sheet made from papyrus pulp was usually written on only one side and stored as a scroll . Skilful production made it possible to roll rolls well over 20 meters.

This unwieldy type of storage was replaced by the codex from the first century , which essentially corresponds to today's book form. The more easily foldable parchment that slowly took the place of the papyrus encouraged this new shape. Its origin can be traced back to the 3rd century BC, to the Greek Pergamon , from which the name is also derived. While the new writing material was soon used for manuscripts , it was only used hesitantly for documents. It was only under Benedict VIII at the beginning of the 11th century that the Vatican switched from papyrus to parchment.

This negative behavior was repeated with the introduction of the paper . The writing material, which was probably invented in ancient China , found its way to Europe via Arabia and Spain , where the Moors introduced it in the 11th century. In Germany, the register book of the canon and dean of Passau Albert Behaim, begun in 1246, is considered the first paper manuscript. Like parchment before it, paper was for a long time banned as a carrier for documents. According to the Padua Statute of 1236, paper documents had no legal force. In the later centuries the use of paper itself led to the suppression of certain fonts, such as Textura , which are not particularly suitable for paper, in favor of Bastarda .

Pens and nibs

The Egyptians used reed springs to put hieratic writing on papyrus. The hieroglyphs carved in the stone have a significantly different shape. The same can be seen with the Greeks and Romans. The completion of a capitalis monumentalis comes from the tools of the stonemasons. The scribes, on the other hand, used a stylus (lat. Stilus ) for wax tablets or sharpened reeds (lat. Calamus ), in the tip of which a gap was cut to facilitate the flow of ink. From the 6th or 7th century bird feathers, especially goose quills , appeared as writing implements. The brush as a writing instrument was rarely used, for example for golden lettering or elaborate initials . A sharp knife was very important in order to be able to sharpen the writing implements, the tips of which quickly became blunt or frayed, if necessary. The scribes always had a sharp knife, the rasorium , ready for mending small spelling mistakes , with which they could scrape off the corresponding parts of the parchment. With the introduction of the cheap, but not very resistant paper, this soon became superfluous.

The hardening of the goose quill

Goose feathers (goose quills) are hardened before they can be used for writing. The so-called "pulling" of the feathers requires some practice. Hardening is done by heating the feather either in hot sand or in hot ash, or by moving the keel back and forth over a strong heat source (not an open fire) until it is evenly softened. If the heat is too strong or too low, the keel will not get the necessary hardness afterwards and will splinter and develop "teeth" when it is cut. Then the top skin of the keel is scraped off evenly on all sides with the help of a knife on a soft surface. The keel must then be pressed back into its original round shape while it is still warm. The easiest way to do this is to pull the keel through a soft cloth several times. If it is prepared in this way, it can finally be cut. For successful writing with a goose quill, the writing pad had to be inclined between 40 and 60% so that the ink did not flow out of the pen too quickly.

Modern pens and papers

Nowadays goose feathers are only used for special tasks, e.g. B. particularly fine lines are used. They were replaced by steel springs. Modern broad or ribbon tension nibs have a small ink tank on the top, which allows you to write several words without having to pick up ink again. The most widespread in Europe are manufactured by the Brause company and are available in different line widths from 0.5 mm to 5 mm.

If the font should have a special character, modern calligraphers also resort to brushes or construct the font with a ruler and pencil. There are also special calligraphy fountain pens that have a wide tip. They usually do not achieve the typeface of a steel nib and are more expensive to buy. Owing to the ink cartridges, frequent refilling of ink is not necessary. In addition, a wide range of pens, rollerball pens, special round and copperplate nibs is available from specialist retailers.

Writing and handicraft shops offer inks and inks of sufficiently good quality for most calligraphic needs. In addition to colored inks, gold leaf is also easy to get. Today, paper is mostly used as a writing material. Papyrus and parchment are available to order, but at prices that do not justify a normal calligraphic project. In addition, paper is more manageable in many cases and can be used in a variety of ways thanks to the different possible colors and structures.

history

In the course of history, new writing implements and writing materials, political and cultural changes and technical progress have repeatedly led to challenges that have influenced the development of calligraphy and calligraphic techniques and scripts.

These developments continue to have an impact today, as modern calligraphic works are inspired by historical models and these models thus become the starting point for today's calligraphic work.

The following historical overview shows the influence of the respective epochs on the development of today's western calligraphy. For the scientific picture of the history of Latin script cf. the article Latin Paleography .

Calligraphy in ancient times

Even in ancient Egypt , particularly important documents were written in the more beautiful hieratic hieroglyphs , while the much more practical demotic script was used in everyday correspondence . With the invention of the reed pen and papyrus , it was possible to quickly create, copy and distribute documents and scrolls . This also increased the need for skilled scribes who designed the scrolls both legibly and artistically.

At the beginning of the first millennium BC, a new era began with the development of the Phoenician alphabet . Merchants and traders spread it all over the Mediterranean, and soon afterwards the Greeks created an alphabet based on this model, which in its basic form is still used today.

From this, in turn, the Etruscans developed their own and from it the Latin alphabet , which the Romans adopted, and that, with a few exceptions (these are the letters H, K, Y and Z and the newer letters J, U and W taken from the Greek ), corresponds to our current script. It had already matured in the time of Cicero and Caesar and was perfected in the form of the Capitalis monumentalis , a font for buildings and triumphal arches created by stone masons . You can see the latter today on the remains, for example in the Roman Forum , especially on the Trajan Column . The Romans only knew and used today's capital letters , the lower case letters only developed in the course of the early Middle Ages .

It was also the Romans who developed today's book form. For quick writing, they developed wax tablets ( tabellae or codices ) that could be written on with a stylus and then erased with the flat back. Two or three of these tablets were bound together and thus formed the basis for so-called codices bound from parchment .

The middle age

Historical overview

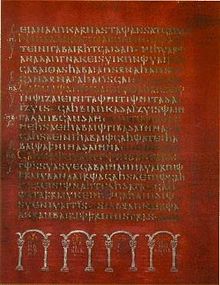

Early Christianity promoted the development of the art of writing through a high demand for elaborate copies of the Bible and other sacred texts. In monasteries all over Europe, the wills were copied on the basis of the Latin script. Some particularly important pieces were written on purple-stained parchment with gold or silver ink. In the large area where the Latin script was used after the collapse of the Roman Empire , very different writing styles developed. By 800 this phenomenon was so advanced that even people with good writing skills had difficulty reading texts from other regions. Therefore, Charlemagne appointed his court theologian Alcuin of York, the abbot of St. Martin in Tours, to develop a script that was easy to read and that was to be used throughout the Carolingian Empire. This Carolingian minuscule was used until the 11th century.

Before that, a large number of fonts had already developed. The most important, the uncial , had been used in North Africa since the 2nd century and from there found its way to Europe via the remains of the Roman Empire. She experienced influences of different currents, so that, among other things, the so-called semi - uncial developed, which is already clearly reminiscent of our lowercase letters . Irish and Scottish monks took up uncials and semi-uncials and developed the insular scripts or Celtic Hand from them . The name already reveals that Celtic influences and traditions of the writers also flowed into this. In the second half of the 7th century, the Book of Kells , which is now famous for its lavish decorations and is a tourist attraction in Dublin's Trinity College , was the first highlight of Christian book art .

From the 11th century the broken or Gothic scripts emerged (analogous to the architectural style of the time, the Gothic ). This font style, also known under the name Textura , is related to the high prices for writing material at the time. Due to the dense shape of the letters, a lot of text could be accommodated in a small space. Another phenomenon of this scarcity of raw materials are the so-called palimpsests . These are old documents that have been "recycled" by medieval scribes. The old writings were scraped off and the parchment was rewritten. As a result, as paradoxical as it may sound, many ancient writings have been preserved. Because instead of simply throwing away the old books, they have been rewritten and kept until today. In the meantime, however, the old text remains can be reconstructed using chemical methods or examinations under UV light .

While the whole of Europe was writing more and more angular, Italian writers opposed this trend in writing, at least in part. They created a more rounded form of Gothic script called the rotunda . It was easier to read and therefore was preferred in liturgical books that were read from during the service.

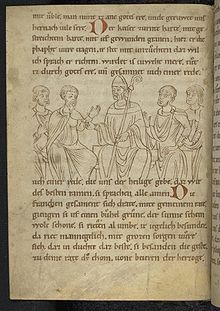

In the Middle Ages found Illumination and calligraphy another heyday. Magnificent manuscripts were produced in the monasteries for ecclesiastical and, in aristocratic circles, private use, embellished with miniatures and initials .

In addition to the broken fonts, officials and merchants developed cursive fonts that , as so-called bastard fonts, met calligraphic requirements. The name identifies them as “not pure teaching”, although they have been written at the highest level (e.g. Bourguignonne ).

Design of a medieval codex

In a medieval office, the principle of division of labor already prevailed to a certain degree of perfection. In order to be able to supply the magnificent manuscripts for the great needs of the churches and monasteries, the scribes concentrated only on the text. The works began without a title page, only with an introductory formula, mostly incipit (lat. "Here begins"). Before writing the pages were using a bone folder liniiert or the lines defined by small holes. This had the advantage that they were congruent on the front and back. Experienced writers could copy many a book in just a month.

The "Rubricator" followed the scribe. He wrote the chapter headings in red (Latin ruber ) ink and marked the first letters with red or blue lines. The word “ rubric ” is derived from this work .

Only then did the illuminator paint the pages with the artistic miniatures or initials. He used brushes made from the tail hair of squirrels and watercolors made from color pigments bound with gum arabic or egg white. Each color of a miniature has its own story. For example, ultramarine blue was extracted from crushed lapis lazuli that was shipped over the ocean (ultra marine) . The bright red often came from cinnabar (mercury sulfide), which was called minium in the Middle Ages and thus gave the miniatures their name. So originally it has nothing to do with their size.

Important writing rooms of the Middle Ages

Manuscripts and miniatures were made in many places in the Middle Ages. However, monasteries had the opportunity to create particularly excellent works. Some important places in the German-speaking area were the monasteries Aachen , Seeon and St. Gallen in Carolingian times and Mittelzell in Reichenau, Trier , Echternach , Cologne , Fulda , Minden , Hildesheim , Magdeburg and the monastery Sankt Emmeram in Regensburg in the high Middle Ages .

When investigating scientists in many archives of the Middle Ages such. In the course of the past 100 years, for example in the Arezzo cathedral archives or monastery holdings, a number of valuable manuscripts and documents have been found to be forgeries that were supposed to legally secure territorial claims or donations. 60% of all royal documents of the Merovingian era were forged by monasteries, at the end of the 1990s Mark Mersiowsky checked the 474 documents received by Ludwig the Pious and sorted out 54 diplomas as forgeries, some of which were quite clumsy, but often also deceptively real documents which were almost perfect in the writing and manufacture of the seal, together with the string suspension: “With the stroke of a pen, monasteries attested to customs privileges. They sacked huge estates, granted tax exemption or immunity. If the nobility contested their possession, they countered with parchments with imperial seals dangling from them. ”Among the most creative forgers were Wibald von Stablo , head of the Saxon imperial abbey of Corvey , Petrus Diaconus , librarian from the Montecassino monastery , and finally Guido von Vienne , who ran it thanks to his inflection of truth even when Pope brought Kalixt II to the highest dignity in 1119. However, everything was surpassed by the so-called Constantinian donation of the 8th century. This document, supposedly dating from the 4th century, was intended to secure extensive areas of worldly property for the church and to manifest the Pope's claim to power over the emperor.

In addition, manuscripts were also commissioned by private individuals in monasteries or from independent artists. In the name of rich noblemen and traders, expensive and famous works were created, e.g. As the Book of Hours Très Riches Heures of the Duke of Berry .

The increase in the demand for books after the founding of the first universities encouraged the creation of private writing rooms. They dedicated themselves specifically to the textbooks that the students needed, but also to devotional writings for private individuals. The professors' new works, which had to be reproduced, ensured their turnover. Even the monasteries of the late Middle Ages hired freelance scribes and trained non-monks. As a result, the quality of the books often decreased as their number increased. Richard de Bury, Bishop of Durham , wrote about this in the 14th century, the monks devoted themselves more to emptying the beakers than to writing codices.

With the advent of humanism and inexpensive paper as a writing material, contemporaries began to copy works themselves. This encouraged resourceful dealers to have large numbers of contemporary literature books copied cheaply by many writers and to sell them to middle-class customers. Their reputation was rather dubious in the circles of educated citizens.

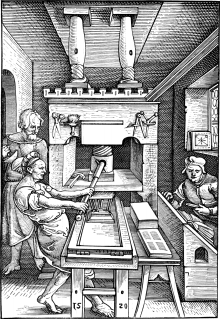

Book printing as a challenge

After the invention of printing with movable letters by Johann Gutenberg in the 15th century handwritten and hand-decorated books lost steadily in importance. The beauty of the painted and illuminated pages was given up in favor of the cost-effective production of a large edition, which the new technology allowed. However, many texts still had to be written by hand. These manuscripts certainly had an influence on the development of the letter forms for the printers' letters. In Italian calligraphy at the time of the Renaissance, the Antiqua and the humanistic cursive , fonts that are still in use today, emerged.

In Germany, the broken script was also used in the printing industry. In the form of Fraktur and Schwabacher , which developed from the Bastard scripts and the Textura, they were used until the 1940s.

The time of codices and miniatures ended in the 16th century. Book printing is also slowly gaining ground in the illustration of expensive works, and even Spanish and Flemish artists are turning to large-scale painting.

Modern western calligraphy

The art form calligraphy

At the end of the 19th century, calligraphy was rediscovered by William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement and made available to a wider class of people. Many famous typeface artists such as Edward Johnston , who developed the Foundational Hand and the London Underground's font , the Johnston Sans , and Eric Gill were influenced by Morris. In Germany, Rudolf Koch further developed Fraktur and Schwabacher at the beginning of the 20th century.

Two important contemporary type artists are Arthur Baker and Hermann Zapf . Fonts developed by them can also be found on many computers today; B. Baker Signet or ITC Zapf Book.

In everyday life

Since handwritten forms of communication have become rare, calligraphy is mostly only used for special occasions such as addressing wedding invitations and important announcements. “Computers, e-mail, but also telephones and cell phones: all these useful facilities will probably contribute to the fact that those beautiful, meticulous manuscripts that can be admired in the archives will be produced less often in the future than in previous centuries. Nevertheless, there is still no reason to believe that writing with your own hand will be completely lost in the foreseeable future. Observation teaches that the so-called 'obsolete' or 'obsolete' very often persists - even if not necessarily in its original function. ”By concentrating on text and work, the stress of everyday life can be switched off and a calm emotional state can be achieved. A quote from Andreas Schenk reflects this fact: "The calm of this work fills the whole being with a comprehensive satisfaction, where time and space, for a short time as if wiped away, no longer bother us nor burden us".

The most common fonts that are used in calligraphy today are advanced forms of the uncials , which are particularly used in modern churches, the Textura , the Fraktur and the Humanistic Italic .

Learn calligraphy

There are two main ways to discover calligraphy for yourself. On the one hand, autodidactically , by experimenting yourself or learning from a textbook (→ lit. ). The second option are calligraphy courses from different providers. Evangelical and Catholic educational institutions as well as some adult education centers offer courses in calligraphy in which you can learn at least the basic techniques.

In contrast to many other art forms, all you need to get started is a broad pen and ink. However, other techniques always present more challenges. The inclination of the nib or variations in the writing angle between the base line and the nib are not self-evident even for an experienced writer. And in order to ensure the uniformity of the letters in a large work, he has to remain focused and be able to write with routine.

Calligraphic fonts

Since the Egyptians one can distinguish between two font styles: straight and italic fonts. Fonts in particular were used in official texts and religious manuscripts, while italics were mostly formed from these by writing faster. This resulted in typefaces for daily correspondence that were quick and practical, but often lost legibility. With the beginning of book printing, this division changed. Script and italics were used in the printed text, while handwriting developed its own scripts, for example the copperplate , our Latin script or, in 19th century Germany, the German Kurrent script .

Within the Latin script continues to distinguish between writings (only capital letters capitals called or capital letters) are made, such as the Roman square capitals or uncials , the writings, the only (also lowercase cursive called) are, like the Carolingian minuscule , and fonts that consist of uppercase and lowercase letters, such as the Antiqua or Fraktur . The latter were not used until the 8th century, when scribes began to specially mark the first letters of the manuscripts.

Development of calligraphic fonts

The following table provides an overview of the origin and use of important calligraphic fonts. The column “affects” describes which fonts were influenced by the respective style. Explained the guy behind the name, whether it is a a font in uppercase, lowercase, just writing (with upper and lower case), italic or cursive writing is. The indication of the centuries is an approximate value, as the scripts have prevailed at different speeds in different regions of Europe.

| Century | Font (type) | example | affects |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10th v. Chr. | Phoenician (capital letters) | Greek , Hebrew , Arabic | |

| 10th v. Chr. | Greek (capital letters) | Etruscan , Old Italian scripts | |

| 8th v. Chr. | Etruscan (capital letters) | Latin | |

| 6th v. Chr. | Latin (capital letters) | Capitalis | |

| 1st v. Chr. | Capitalis (capitals) |

|

Uncials , Antiqua (capital letters), Humanistic italics (capital letters) |

| 2. | Uncial (capitals) | Insular fonts , semi-uncials , Lombard capital letters | |

| 5. | Semi-uncial (capitals) | Insular writings , Carolingian minuscule | |

| 8th. | Carolingian minuscule (minuscule) | Textura , Rotunda , Antiqua (minuscules), Humanistic cursive (minuscules), | |

| Insular fonts (uppercase and lowercase) | |||

| 11-15 | Textura (straight) | Schwabacher , Fraktur , bastard fonts | |

| Bastard fonts (italics) | Schwabacher , Fraktur | ||

| Rotunda (straight) | Antiqua | ||

| Lombard capital letters (capitals) | Antiqua | ||

| 14.-17. | Schwabacher (straight) | German current script , Fraktur | |

| Antiqua (straight) | Modern font | ||

| Humanistic italics (italics) | Modern font , copperplate , Latin script | ||

| Fracture (straight) | German current script | ||

| 16. | Copperplate or English cursive (cursive) | Latin script | |

| 20th | Modern fonts |

|

See also

To calligraphy

- Calligraphy : Overview (Category: Calligraphy )

- Arabic calligraphy : Calligraphy in Islam

- Chinese calligraphy

- Shodō : the way of writing in Japan

- Book illumination

History of writing

- Paleography and the history of writing : evolution of our alphabet

Fonts

- Antiquity to early Middle Ages: Capitalis , Uncials , Carolingian minuscules

- Broken fonts : Textura , Rotunda , Fraktur , Schwabacher , Deutsche Kurrentschrift

- Renaissance to Modern: Antiqua , Humanistic Italic , Copperplate

literature

Text and learning books

- Christine Hartmann: Calligraphy . Bassermann, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-8094-1564-2 .

- Julius de Goede: Calligraphy for beginners . Knaur, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-426-66843-2 .

- Julius de Goede: The most beautiful calligraphic alphabets . Knaur, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-426-64104-6 .

- Calligraphy . area verlag, Erftstadt 2004, ISBN 3-89996-130-7 .

- David Harris: The Art of Writing . Urania, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-363-00974-7 .

- David Harris: The Great Handbook of Calligraphy, 100 alphabets with detailed instructions . Weltbild, Augsburg 2003, ISBN 3-8289-2460-3 .

- Bruce Robertson: Intensive Writing and Calligraphy Course . Augustus Verlag, Augsburg 1999, ISBN 3-8043-0646-2 .

- Judy Kastin: 100 Great Calligraphy Tips . Quarto, London 1996, ISBN 0-7134-7949-3 .

- Timothy Noad: The Art of Illuminated Letters . Headline, London 1995, ISBN 0-7472-1112-4 .

- Hans Maierhofer: Calligraphy - from form to letter . Urania, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-332-01952-0 .

- Hans Maierhofer: 7-day beginner's program in calligraphy . Urania, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-332-01866-3 .

- Andres Schenk: Calligraphy - The silent art of wielding a pen . AT Verlag, Aarau 1991, ISBN 3-85502-375-1 .

Books on calligraphy and writing

- Giulia Bologna: manuscripts and miniatures . Weltbild, Augsburg 1995, ISBN 3-86047-112-0 .

- Carl Faulmann : The Book of Scripture . Weltbild, Augsburg 2004, ISBN 3-8289-0799-7 .

- Georges Jean: The History of Writing . Ravensburger Buchverlag, Ravensburg 1991, ISBN 3-473-51018-1 .

- Albert Kapr : Font Art, History, Anatomy and Beauty of the Latin Letters. Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1996, ISBN 3-364-00624-5 .

- Josef Kirmeier (Hrsg.): The art of writing: Medieval book illumination from the Seeon monastery. House of History, Augsburg 1994, ISBN 3-927233-35-8 .

- Sigrid Krämer, Michael Bernhard: Manuscript heritage of the German Middle Ages. Beck, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-406-34812-2 (= medieval library catalogs in Germany and Switzerland ).

- Andrea Rapp, Michael Embach (ed.): Reconstruction and indexing of medieval libraries: New forms of manuscript presentation. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-05-004320-3 .

Web links

- Kallipos.de : Extensive calligraphy page with instructions, alphabet templates and text examples as well as an online pen museum

- Kalligraphie.de : German-language portal for calligraphy

- Schreibereien.de : Portal for calligraphy with a calligraphy forum

- Fontart.de of the calligrapher Hans Maierhofer

- Ars Scribendi : International Society for the Promotion of Literature and Writing Art

- Manuscript "portal" of the library of the Germanisches Nationalmuseum

- Scriptorium - Book Production in the Middle Ages - www.ub.uni-heidelberg.de ( Memento from October 22, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Photo gallery and explanation of the production of papyrus

- ↑ Codicology: Writing materials. In: http://kulturschnitte.de . Retrieved February 19, 2019 .

- ^ Harry Bresslau : Papyrus and parchment in the papal chancellery up to the middle of the 11th century. In: Communications from the Institute for Austrian Historical Research . Volume 9, 1888, pp. 1-33 (accessed via De Gruyter Online); Leo Santifaller : Contributions to the history of writing materials in the Middle Ages with special consideration of the papal chancellery (= communications from the Institute for Austrian Historical Research. Supplementary volume 16). Volume 1: Investigations. Böhlau, Graz et al. 1953.

- ↑ Margarete Rehm: Information and communication in the past and present. ( Memento of the original from August 24, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. On: ib.hu-berlin.de

- ↑ Chronology of book and library history. In: http://www.bib-bvb.de . Bayerische Beamtenfachhochschule - Department of Archives and Libraries, September 1999, archived from the original on February 6, 2006 ; accessed on February 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Codicology: Writing materials. In: http://kulturschnitte.de . Retrieved February 18, 2019 .

- ↑ Capitalis Monumentalis. In: typolexikon.de .

- ↑ Goose Quill. On: kalligraphie.com .

- ↑ Different image and result examples of different spring types ( Memento of the original from August 28, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Examples of tension springs

- ↑ Writing instructions for band tension springs

- ↑ Hasnain Kazim: Fountain pen manufacturer: Savior of handwriting. In: Spiegel Online. July 6, 2008, accessed February 18, 2019 .

- ^ Viktor Thiel: Paper production and paper trade mainly in the German lands from the earliest times to the beginning of the 19th century. A blueprint. In: Archival Journal. 41 / Third Part 8, 1932, pp. 106–151. (PDF, 4,326 KB)

- ↑ a b Josef Kirmeier (ed.): The art of writing: Medieval book illumination from the Seeon monastery. House of History, Augsburg 1994, ISBN 3-927233-35-8 .

- ↑ Peter Ochsenbein: The St. Gallen Monastery in the Middle Ages . Theiss 1999, ISBN 3-8062-1378-X .

- ↑ swissinfo.ch: Unesco World Heritage in Switzerland - St. Gallen Monastery: Books as medicine for the mind

- ^ Gabriele Häussermann: Life and work of the Baden court painter Georg Otto Eduard Saal (1817 - 1870). (PDF, 3.0 MB) Dissertation. Albert Ludwig University, Freiburg i. Br. 2004.

- ^ The scriptorium

- ^ Arnold Angenendt: Willibrord, Echternach and the Lower Rhine. New observations on old questions. Calendar for the Klever Land - To the year 1968. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Kleve 1967, p. 22ff.

- ↑ Kaiser Gospels, Codex Aureus Escorialensis. Echternach 1045/46 ( Memento of the original dated August 29, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Christiane Hoffmanns: Faith and Knowledge in the Middle Ages: The high art of book making . To the exhibition of the Diozesanmusuems Köln for the cathedral anniversary . In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt . 95 (42), pp. A-2646 / B-2254 / C-2118.

- ↑ Joachim M. Plotzek: The History of Cologne Cathedral Library . ( Memento of the original from February 20, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Belief and Knowledge in the Middle Ages. Catalog book for the exhibition. Munich 1998, pp. 15-64.

- ^ Eduard Krieg: Rabanus Maurus - The most learned abbot from Fulda and Praeceptor Germaniae. ( Memento of the original from July 14, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Kurt Pfister: The medieval book illumination of the west . Holbein Verlag, Munich 1922, full text edition on archive.org.

- ^ Library of the Art Museum Monastery of Our Dear Women , Magdeburg

- ↑ On the challenge of the closed tradition: Martin Germann (curator of the Bibliotheca Bongarsiana, Burgerbibliothek Bern): Why medieval book collections should be preserved intact. 2006.

- ↑ Horst Fuhrmann : Influence and distribution of the pseudoisidoric forgeries. From their emergence to modern times . Writings of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica Vol. 24, 1972/74.

- ^ Forgeries in the Middle Ages. International Congress of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica Munich, 16.-19. September 1986. 5 text volumes and 1 register volume , Munich 1988/1990, ISBN 3-7752-5155-3 (writings of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica. Vol. 33)

- ↑ Cf. Mark Mersiowsky: The document in the Carolingian era. Originals, document practice and political communication. Writings of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica Vol. 60, 2010, ISBN 978-3-7752-5760-0 .

- ^ Matthias Schulz: Vertigo in the scriptorium . In: Der Spiegel . No. 29, July 13, 1998.

- ↑ Erich Wenneker : Western calligraphy. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 13, Bautz, Herzberg 1998, ISBN 3-88309-072-7 , Sp. 1029-1034.

- ↑ Erich Caspar : Petrus Diaconus and the Monte Cassinenser forgeries. A contribution to the history of Italian intellectual life in the Middle Ages. Springer, Berlin 1909.

- ^ Beate Schilling: Guido von Vienne - Kalixt II. Hahn-Verlag, Hanover 1998.

- ^ Horst Fuhrmann : Donation of Constantine and Occidental Empire . In: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages . (DA) 22 (1966), p. 63 ff.

- ^ Raymond Cazelles , Johannes Rathofer: The book of hours of the Duc de Berry. Les Tres Riches Heures. VMA-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1996, ISBN 3-928127-31-4 .

- ^ Johanna Christine Gummlich: The exhibition ars vivendi - ARS MORIENDI. The art to live. The art of dying in the Diözesanmuseum Cologne . In: From the second-hand bookshop . tape 4/2002 , 2002, p. A 216 - A 219 ( archive.org [accessed February 19, 2019]).

- Jump up ↑ Richard Bury, Ernest Chester Thomas: The Philobiblon of Richard de Bury, bishop of Durham, treasurer and chancellor of Edward III. BiblioBazaar, 2009, ISBN 978-1-116-90416-1 .

- ↑ Elizabeth L. Eisenstein: The printing press. Vienna / New York 1997; (Abstract).

- ↑ Lotte Kurras: Norica: Nuremberg manuscripts of the early modern times . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1983.

- ↑ Representation of the development of Antiqua with type examples

- ↑ Günter Schuler: A man against time? William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement ; (PDF, 174 kB).

- ^ The Arts and Crafts Home: Movement Histories

- ^ The Legacy of Edward Johnston - The Edward Johnston Foundation

- ↑ Rudolf Koch: A memorial for the writing master. (No longer available online.) In: moorstation.org. Archived from the original on October 26, 2015 ; accessed on February 18, 2019 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Wilhelm Hermann Lange, Martin Hermersdorf: Rudolf Koch, a German writing master. Heintze & Blanckertz, Berlin 1938.

- ↑ Biographical sketch of Arthur Baker (English).

- ↑ Zapf's autobiography at Linotype (PDF)

- ↑ Font weights of Zapf's fonts at Linotype ( Memento of the original from November 19, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Iris Mainka: I email, therefore I am. In: The time . May 8, 2008.

- ↑ Johannes Burkhardt , Christine Werkstetter (ed.): Communication and media in the early modern times. ( Historical magazine Vol. 41. Supplement) Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2005, p. 413: "Almost all known major correspondence from the period 1500-1800 used the [handwritten] letter as a news medium".

- ↑ Hermann Schlösser: The uncertain fate of handwriting in the age of the computer. Manual or digital? In: Wiener Zeitung . June 24, 2005 (accessed November 6, 2013).

- ^ Homepage of the Basel calligrapher Andreas Schenk

- ↑ Examples of images for the Humanistic Italic ( Memento of the original from June 8, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Example: Calligraphy Center Bernese Oberland

- ↑ http://www.vhs-saulheim.de/kurse/Kaligrafie.html

- ↑ Calligraphy: The Humanist Cursive - a time-honored and yet so contemporary script ( Memento of the original from December 11, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ As a textbook for German Kurrent, Sütterlin script and Offenbach script ; Harald Suss: German script. Learn to read and write. Verlag Droemer Knaur, 2002, ISBN 3-426-66753-3 .