Algernon Sidney

Algernon Sidney (born January 14 / January 15, 1623 in Baynard's Castle, London , † December 7, 1683 in London) was an English politician , a political philosopher and an opponent of Charles II of England . With his opus Reflections on Forms of Government he influenced John Locke and the American Declaration of Independence and the American Constitution .

Life

Algernon Sidney was born in Baynard's Castle in London in 1623 as the second son of Robert Sidney, 2nd Earl of Leicester .

Under the reign of Charles I (1625–1649)

origin

His parents came from old English noble families. His mother Dorothy was a Percy. Her family, the Earls of Northumberland, were known for their deep understanding of honor and martial arts - and for their rebellion against kings. In "Richard II." And "Henry IV." Describes William Shakespeare Henry de Percy , who overthrew a king and fought against another.

The Sidney side of the family was more educated and learned. Best known is his great-uncle Sir Philip Sidney , who was a poet and favorite at the court of Queen Elizabeth I and who died 37 years before the birth of Algernon Sidney. Algernon Sidney admired him. He emulated him in his thirst for knowledge as much as in the fighting spirit with which his great-uncle lost his life in the battle of Zuphten .

Childhood and youth

Algernon Sidney spent his early childhood in Penshurst, which was the family seat in Kent . His father was a diplomat and a scholar in his field. Its extensive library contained thousands of books on philosophy , politics , history, and religion, both ancient and contemporary. The Earl of Leicester taught his children himself. He took his two sons with him when he had to move to Rendsburg in 1632 as the English ambassador to the court of King Christian IV of Denmark . The Thirty Years' War was already raging on the European mainland , in which Denmark and Sweden fought for supremacy in the Baltic region . Both sons also came to Paris in May 1636 when their father was there at the court of King Louis XIII. of France had to represent English interests. In France , his father had a deep friendship with the Dutch lawyer and famous political philosopher Hugo Grotius , who was the Swedish ambassador to the French court. In his notes and reports, the Earl presented his views as being equivalent to those of other political thinkers. Many years later it was reported that Algernon named Sidney Grotius' On the Law of War and Peace " as the most important of all books that dealt with political theory.

Algernon Sidney and his brother

At the court in France, Algernon Sidney developed quickly and was popular in society. His mother wrote in a letter to her husband dated November 10, 1636 that “she hears only good things about him [Algernon Sidney] from everyone who comes from there [Paris], from his excessive understanding and as much as from his amiable Essence ”( George Van Santvord :). In his life there was always a question of a fundamental nature as to whether people are entitled to rule by virtue of their firstborn or by God's grace. Later he should argue that the claim to power must be acquired through merit and not through birth and that this can most likely be achieved in a republic. His older brother Phillip, the future Earl of Leicester, was said to be "stupid, lazy and depraved" , while Algernon was described as "witty, energetic and honorable" . Her father later tried to make up for the difference by disinheriting Algernon's brother on important points and giving as much as possible to his second eldest son.

The English Civil War

In 1641 the Irish rose up under the leadership of Rory O'More and conquered Dublin . Algernon Sidney went to war with his brother Philip, who had to lead his father's cavalry regiment for the Earl, in October 1641, while her father was taking up the post of English envoy in Rome. In the fight against the insurgents, Algernon Sidney distinguished himself several times for bravery in front of the enemy. He received his father's lieutenant patent, followed by other awards, and returned to England as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland with his brother in August 1643 , where he was surprised by the English civil war that had now broken out between King Charles I of England and Parliament. In Lancashire both received the king's order to join him at Oxford .

Parliament learned of this, had them both "detained for their protection" and taken to London. In London it took little effort to convince Algernon Sidney to join the army of Parliament. The king thought the matter a pre-arranged game and was convinced of their betrayal, since in his opinion they should have resisted and fled. In this situation it was easy for Algernon Sidney to take the side of Parliament, especially since Parliament granted him £ 2,000 to pay off his debts. In this civil war he now belonged to the supporters of parliament, known as "Roundheads" or round heads, who fought against the supporters of the king, the so-called "Cavaliers" . Already on May 10, 1644 he was appointed captain of the cavalry, which was under the Earl of Manchester. A short time later he was promoted to lieutenant colonel. In one of the decisive battles at Marston Moor on July 2, 1644, he moved to the head of his regiment and was seriously wounded. He was only able to save himself from capture with difficulty. An eyewitness reported that "Colonel Sidney at the head of the cavalry regiment of my Lord Manchester led the attack with such bravery and with many wounds emerged from it the true badges of his honor." On April 2, 1645 he received the supreme command of a cavalry regiment, which belonged to Oliver Cromwell's division in General Thomas Fairfax's army.

On May 10, 1645, Algernon Sidney became governor of Chichester in southern England. Oliver Cromwell defeated the royalist troops at the Battle of Naseby on June 14, 1645. It was the final decisive battle. In September the King's Highland Partisans were defeated by the Scottish Army, and Charles I surrendered to the Scottish Army on May 5, 1646. In the meantime, Algernon Sidney had been a member of Parliament since December 1645, which initially sat in Cardiff in south-west England.

In July 1646, Algernon Sidney went to Ireland , where his brother was Lord Lieutenant, and was appointed Lieutenant General of the Cavalry and Governor of Dublin . From 1648 to 1651 he was Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports .

Affair with Lucy Walter

In the midst of the Civil War, twenty-five year old Algernon Sidney met the beautiful, exciting, but simple Lucy Walter . She was only seventeen and was just being introduced into London society after her noble family had lost all their belongings in taking the king's side. Lucy Walter became his mistress . The affair lasted a year before she became his brother Robert's lover.

In the Commonwealth (1649-1660)

Parliamentary work

On May 7, 1647, Algernon Sidney received thanks from the House of Commons for his good service in Ireland and was subsequently appointed Governor of Dover . After a series of setbacks, King Charles I fled to join the Scottish army. In June 1647, however, he was extradited to the English Parliament because he did not want to join the Presbyterian Church . In London, the parliamentary groups and Oliver Cromwell tried to come to an agreement with King Charles I on state reform. Charles I tacted, played individual groups against each other and made promises to get the Presbyterian Scots to rise again against the English Parliament. Oliver Cromwell put down the rebellion and took King Charles I prisoner on the Isle of Wight . He and his followers, the so-called Independents , forced the English parliament to pass a law that regarded further negotiations with Charles I as high treason. During this time, Algernon Sidney was in opposition to the Presbyterian Party and on the side of the Independents, but criticized Oliver Cromwell and his supporters when they ousted the more moderate MPs from parliament. The remaining MPs, the so-called "rump parliament", set up a court that was supposed to judge the king and was appointed to the Algernon Sidney. On January 20, 1649, the trial began at Westminster Hall . Charles I denied the court any legality and refused to comment on the indictment. Algernon Sidney had doubts about the legality of the trial as much as about the impartiality of the court, especially since the trial was driven by Oliver Cromwell and his supporters.

He only took part in the proceedings of the court on January 13, 15 and 19, 1649. However, on the day of the vote - it was January 27, 1649 - he did not appear and refused to sign the execution record. King Charles I was nevertheless found guilty and beheaded on January 30, 1649 in Whitehall , London. Algernon Sidney would later describe his execution as "the most just and intrepid act ever undertaken in England or anywhere else".

On May 15, 1649, Algernon Sidney was a member of the committee to regulate the succession and future parliamentary elections. In March 1651 he lost his governorship of Dover , presumably because of a quarrel with his officers. After that, Sidney, who was still a member of parliament, went to The Hague for four months .

His youngest brother Robert stayed there, who now had an affair with Lucy Walter and, as a royalist, had followed the heir to the throne, Charles II, into exile in The Hague. In 1648 Charles II tried in vain to rush to the aid of his father and the Scots who were allied with him with a fleet. Charles II met Lucy Walter through Robert Sidney, who soon became his first known mistress. Their son, James Scott , who was born on April 9, 1649, was accepted by Charles II without hesitation as his son. He later became Duke of Monmouth and would play a crucial role in the lives of Charles II and Algernon Sidney. All that is known about Algernon Sydney's stay in The Hague is that he had an argument with Lord Oxford at the game and that a duel between mutual friends could only be averted with difficulty.

In August 1651, Algernon Sidney returned to England and has since taken an active part in parliamentary work. On September 3, the Battle of Worcester took place , in which Oliver Cromwell was able to defeat Charles II and his Scottish army. The extent to which Algernon Sidney in The Hague had learned about the plans and preparations for the invasion of Charles II and reported about them cannot be historically proven; in any case, Parliament elected him to the Council of State on November 25, 1651 with great sympathy. In the State Council he opposed all plans of Oliver Cromwell, who tried several times to dissolve parliament in the struggle for his politics. When Oliver Cromwell finally dissolved the rump parliament by force in April 1653, he withdrew to his estates in Penshurst mainly to arrange family matters and viewed the rule of Oliver Cromwell as tyranny .

Retreat to his goods

In 1654 he traveled to The Hague and visited the Dutch ambassador Beverningk, whom he had met in London. It was through him that Sidney became close friends with Johan de Witt , who as a pensioner of Holland largely determined the policy of the United Netherlands from 1653 and ended the first Anglo-Dutch naval war in 1654 with the Westminster Peace Agreement . After his return, Algernon Sidney stayed away from all politics and wrote his first work "Von der Liebe" , although it is unknown what events in his life triggered this topic. Oliver Cromwell died in London on September 3, 1658. His son and successor, Richard Cromwell , as lord protector was unable to maintain the position of power his father had won.

End of the republic and on the way as an English diplomat

In April 1659, the English army deposed him, dissolved the protectorate and restored the rump parliament . In May, Algernon Sidney resumed his parliamentary seat and was again on the Council of State, where he endeavored to put military power below civil power again. While the restoration of the Stuarts in England was slowly spreading, the parliament commissioned him in June 1659 to lead a delegation from abroad, which according to English ideas should mediate the peace between the King of Sweden and the King of Denmark in the " First Northern War " . At that time, the Danes controlled the two sides of the strait that connected the Atlantic Ocean with the Baltic Sea . They imposed exceptionally high taxes on ships that had to pass this strait. The Treaty of Copenhagen of June 16, 1660 ultimately provided that Sweden had full control of its side of the waterway and the Baltic Sea was freely open to all nations except during times of war. As a token of his appreciation, he returned richly gifted from Sweden to Copenhagen on June 28, 1660 , from where he settled in Hamburg to await the events in England.

During the reign of Charles II (1660–1685)

Exile during the Restoration

England had changed in the short time he was away. The parliament, to which Algernon Sidney belonged, had dissolved itself in March 1660. In April, Charles II had an amnesty for his anti-royalist opponents, religious tolerance and his consent to a constitutional monarchy announced from his exile and was proclaimed King of England on May 8, 1660 by the new parliament . Algernon Sidney was ready to follow Parliament as authority and obey the King. But the king demanded more, that he should condemn all his own deeds committed in the republic and ask the king for forgiveness. He couldn't bring himself to take this step.

“When I recall all of my deeds from the Civil War, I cannot find a single one of them that I could consider a violation of justice or honor; this is my strength and - I thank God - so far I enjoy clearer thoughts. If I were to lose it through bad and unworthy submission, acknowledge it as a mistake, ask for forgiveness or the like, from that moment on I would be the most wretched person among the living and the contempt of all people ”

Charles II himself broke his word after his coronation. Despite assurances of impunity, he cruelly executed those who signed his father's death sentence. He also had Oliver Cromwell's body removed from the grave and executed posthumously . Scottish nonconformists and the Presbyterians were persecuted despite his promise to practice religious tolerance.

Although his family were royalists with the exception of himself and his eldest brother, the king's mother arranged that Lord Leiceister no longer had his regular seat next to her at court. Friends, including General George Monck , on no account warned Algernon Sidney to return to England now. As he wrote in a letter to his father, he was to roam the world for seventeen years "as a tramp, abandoned by my friends, poor and known only as a shabby member of a ruined splinter party" .

Period in Italy (1660–1663)

From Hamburg he traveled across Germany via Venice to Rome , where he arrived in November 1660 and, despite his attitudes, was received with great respect and attention by cardinals. In the summer of 1661 he moved to Frascati , where the nephew of the last Pope, Prince Pamfili, gave him accommodation in his Villa de Belvedere and he devoted himself to his studies. Tired of seclusion in Frascati for two years, he wanted to return to political life to vigorously restore the English Republic through writings and conspiracies.

Stopover in Switzerland in 1663

In the summer of 1663 he traveled to Bern , Switzerland , to meet other English republicans in exile. They had all fought in the former army of Oliver Cromwells and were led in Switzerland by his friend General Edmund Ludlow. Like Sidney, he had sat in the rump parliament, but signed the acts of execution against Charles I. An armed uprising against the English monarchy was just as much considered as offering its military services to foreign rulers. In the guest book of the Calvinist Academy in Geneva he signed the following words:

“Sit sanguinis ultor justorum

May there be an avenger of the blood of the righteous!”

Invasion plans (1663-1665)

In September 1663 he traveled on to Brussels , where the famous portrait was created that the painter Justus van Egmont made and now hangs in Penshurst. For his father's sake, he took the advice of Culpepper, a friend of his father's, and offered the English court to join a troop of tried and tested Republican soldiers in the imperial service of Leopold I , who was just being harassed by the Turks . The English court, however, mistrusted him and rejected his request.

In truth, however, he was anxious to prepare a Dutch invasion of England, which he wanted to join with his exile troops. Over the next few months he lived in various German cities and wrote on his “Court Maxims, Discussed and Refelled” . This work, which was an imaginary dialogue between an English monarchist and a republican, was directed against the absolutism of Charles II and was an equally violent call for resistance against the king.

Johan de Witt, who determined the policy of the Dutch Republic and with whom he was friends, could not convince of the need for a Dutch invasion of England. When the second Anglo-Dutch War broke out in 1665 , Charles II sent ten men to Augsburg to carry out an attack on him, which Algernon Sidney only escaped because he was back in The Hague. Again he tried to force the Netherlands to invade England. But it was in vain. After initial success, Charles II had to experience the disgrace during the war that the Dutch fleet penetrated the Thames , burned many English ships and towed the Royal Charles , the flagship of the Royal Navy, to Holland.

Disappointed by the Netherlands, Algernon Sidney traveled to Paris to offer Louis XIV of France an armed uprising in England for a payment of 100,000 kroner. Louis XIV was interested in a weak England, which was not to form an overpowering alliance with other European states against France when it claimed possession of the Netherlands two years later. He gave Sidney Algernon a small sum with the prospect of a larger sum if he could only show "that he was really capable of the things he promised" . Disputes among the exiles, which particularly arose over the imperious nature of Sidney, let the project fail again.

Exile in Languedoc (1665–1677)

Louis XIV granted Algernon Sidney the right to come under his protection and to settle in Languedoc, where he would spend eleven years of his life. In Languedoc he lived as an aristocrat and was known as "Le Compte de Sidney" . There are indications that he had an illegitimate daughter there in the south of France. In August 1670 he appeared again at court in Paris. Louis XIV granted him a pension after Henry Bennet, the Earl of Arlington, had campaigned for the English court to agree. However, King Charles II made it a condition that Algernon Sidney had to return to Languedoc.

Return to England

When his father became seriously ill at the old age of 83 and he felt his end was approaching, he wished to see his son Algernon again. Through his grandson, the Earl of Sunderland and pages of the king, he asked the king to pardon his son and allow him to return. Charles II allowed him to return on condition that he should remain politically quiet. In August 1677, Algernon Sidney returned to his homeland after 17 years and was able to see his father, who died peacefully a few months later on November 2nd. In his will he bequeathed him £ 5,100 and a portion of the annual income from the lands. He also decreed that Algernon and Henry Sidney should execute his will. His older brother contested his inheritance and complained. It took several years in court for the dispute to turn out in favor of Algernon Sidney. A debt to Lord Strangford from his time in Italy, believed to have been settled for a long time, brought him into the debt tower from April to August 1678, until he was able to be released by a judge's order.

England had changed in the seventeen years she had been away. There was a general, essentially unfounded fear of a Catholic Counter-Reformation . Charles II, in his penchant for absolutism, favored his brother Jacob, who had openly converted to the Catholic faith in 1672, as his heir to the throne and brought Parliament against him, which had previously been devoted to him, but now favored his illegitimate, Protestant son Duke of Monmouth. The Earl of Shaftesbury , longtime confidante and chancellor of the king's treasury, also fell away from him in 1672 and became his greatest adversary at the head of parliament. 1678 appeared the seedy Titus Oates . His oath to have uncovered a Catholic conspiracy (" Popish Plot ") to pursue the murder of Charles II in order to make his younger Catholic brother Jacob king, sparked a national hysteria that lasted until 1681 and in the course of which around 35 Catholics innocently lost their lives. Right at the beginning, in December 1678, the House of Commons arrested five Lords from the House of Lords and threw them into the Tower of London .

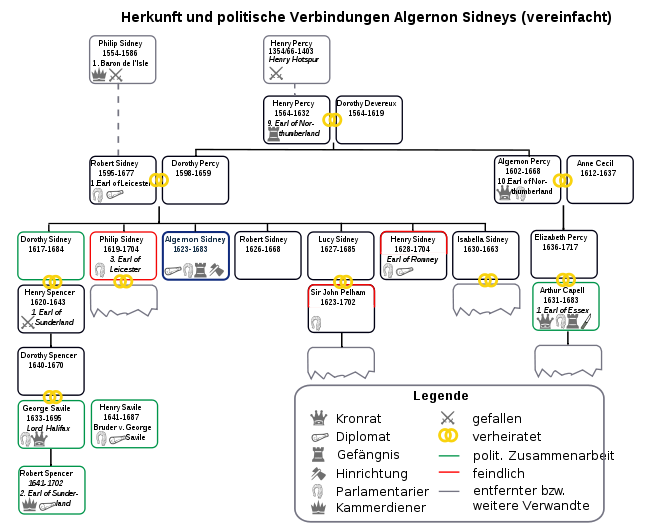

During this turbulent time, Algernon Sidney soon became deeply drawn into politics, especially since he had no doubts about the authenticity of the Popish plot and many in his family were involved in politics. His cousin Arthur Capell, 1st Earl of Essex , his niece's husband George Saville , Lord Halifax, his nephew, Robert Spencer , the Earl of Sunderland and his brother-in-law Sir John Pelham were members of Parliament (see graphic below). His younger brother Henry and his niece's brother-in-law, Henry Savile, were English ambassadors abroad. During this time the country party formed the Whig Party with a huge party apparatus.

When his Chancellor of the Exchequer Thomas Osborne, Earl of Danby for the king came into the line of fire of the parliaments, Charles II unceremoniously dissolved the parliaments in January 1679 to save him. He convened the new parliament for March 16, 1679 in the hope that the next election would bring him a more docile House of Commons.

William Penn , son of a wealthy admiral and leader of the Quakers , was enthusiastic about Sidney's republican beliefs and worked with him on the plan to realize full religious freedom in England. With his support, Sidney applied for a lower house seat for the Quaker community of Guilford, Surrey . It was supposed to be the first of five campaigns in three elections.

The election campaign for the third parliament

| Parliaments in the reign of Charles II | |||||||

| No. | convened | choice | gathered | dissolved | Meetings | Seats | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | March 16, 1660 | 1660 | Apr 25, 1660 | Dec 29, 1660 | 1 | 84 | Convention Parliament |

| 2nd | Feb. 18, 1661 | 1661 | May 8, 1661 | Jan. 24, 1679 | 16 | 83 | Cavalier Parliament |

| 3rd | Jan 25, 1679 | 1679 | March 6, 1679 | July 12, 1679 | 2 | 82 | Habeas Corpus Parliament |

| 4th | July 24, 1679 | 1680 | Oct 21, 1680 | Jan. 18, 1681 | 1 | 81 | Bill of Exclusion Parliament |

| 5th | Jan. 20, 1681 | 1681 | March 21, 1681 | March 28, 1681 | 1 | 80 | Oxford Parliament |

The election seemed very promising at first, until it was brought to Algernon Sidney that the opposing party admitted that he was not eligible because he was not a suitor. In order to avoid being excluded from the election, he turned to the mayor with a request that he be declared Free of the City of Guilford as soon as possible. The mayor promised to discuss the matter with the city elders and to inform Algernon Sidney in good time about the date of the parliamentary elections. The mayor called for early elections the next day, March 1, 1679, which was also market day. The result was when Algernon Sidney presented himself for election, he had to answer “no” to the polling officer when he was asked whether he was a suitor and he was declared ineligible for election in front of the assembled house regardless of the majority of the votes. In the ensuing turmoil and protests, the election was held nonetheless. Some of Sidney's voters were ridiculed and exposed, other votes for Sidney were disregarded as they allegedly mispronounced the name. William Penn, who wanted to support Algernon Sidney as defense attorney, was called in and slandered as a Jesuit by the polling officer and thus suspected of the Popish plot against which there would be ten-by-ten oaths. The mayor then kicked him out and forbade him to appear on behalf of Sidney's party.

The third parliament

The outcome of the Guildford election was clear from the start. The English court had successfully prevented Algernon Sidney from taking the seat in the House of Commons on March 6, 1679. Sidney's petition was forwarded by the House of Commons on March 28, 1679 to the Committee on Privileges and Elections for comment, the report of which was not yet available by the adjournment on May 27. Encouraged by William Penn not to give up hope, he had to be content with the role of observer of the court and parliament for the time being. His two nephews, the Earl of Halifax and the Earl of Sunderland, and his cousin, the Earl of Essex, had now risen to the rank of minister.

It turned out differently than Charles II had hoped. The Committee for Privileges of the House of Commons decided to simply continue the impeachment and lawsuit proceedings against Lord Danby for high treason despite the fact that Parliament had since been dissolved. The House of Commons refused to merely ban a proposal from the House of Lords, Lord Danby. In a Bill of Attainder , the House of Commons had Lord Danby thrown into the Tower of London . The king pardoned him, but the House of Commons invalidated the pardon on May 5th. On May 12th, the debate began, the Habeas Corpus Act to protect citizens from arbitrary arrest was passed while the five Lords from the House of Lords were still in the "Tower of London" . Charles II was most annoyed that the House of Commons tried in a so-called Bill of Exclusion to exclude his brother Jakob, who had publicly professed his Catholic faith since 1669, from the line of succession. On May 27, he adjourned the parliament indefinitely, to dissolve it entirely on July 12, 1679 and to call new elections again.

Algernon Sidney ran for the seat of Parliament for Amersham in Buckinghamshire as well as for that in Bramber in Sussex , in whose parishes there were also many Quakers. With William Penn, he approached his election campaigns more carefully at the end of July this time. Sidney Algernon won the election in Amersham, which took place a few weeks earlier than in Bramber. A completely surprising and unexpected application for Bramber was someone who at that time was still a long way from Bramber, the English ambassador to The Hague in the Netherlands and whose administrator Spencer initially started the election campaign without him - his youngest brother Henry, that of his brother-in-law Sir John Pelham was assisted. Sidney was extremely angry about it, especially since Henry won the election just as surprisingly. The tense relationship with his eldest brother was now joined by his youngest brother and his brother-in-law, John Pelham. Relations with his nephews and his cousin, Lord Essex, became all the more important to him.

Although the elections for the fourth parliament were concluded on all sides, Charles II announced that parliament would be adjourned until January 26, 1680. In a letter to Henry Savile dated October 26, Algernon Sidney wrote:

"I am not even in a position to make a guess as to whether or not Parliament will meet on January 26th, and although I have considered all the circumstances, I am unsure whether I will be part of it or not - it is ( with Roger Hill) a double re-election; and nothing can be considered certain until the question that arises from all of this has been decided. "

So Algernon Sidney decided in November 1679 to travel to Paris for a short time, where his nephew, the Earl of Sunderland, stayed for a short time on a special mission. While Sidney was in Paris, the Earl of Shaftesbury managed to mobilize 150,000 people who marched through London on the occasion of the coronation day of the Protestant Queen Elizabeth I on November 17th and burned a giant Pope doll in protest against the Popish Plot .

After his return to London, Sidney waited for the political situation. On January 26, 1680, the newly elected parliament met briefly, only to hear Charles II's speech, in which he announced that parliament would be adjourned until April 15. Obviously, Charles II wanted to wait until the angry mood against the Popish plot and the attacks on Catholics subsided. The leader of the Whigs, the Earl of Shaftesbury, on the other hand, fueled fear with opinion-making in newspapers and pamphlets. It was a development that began with the conservative Roger L'Estrange , who directed a number of press media in the spirit of the monarchy. Over 1450 pamphlets were created during this time. The Earl of Shaftesbury not only successfully adopted this new form of agitation, but also kept lists of his supporters and opponents, who frequently changed camps. In 1680 London developed into a republican island within the monarchy, so to speak.

In the midst of the struggle for domination opinion of the posthumously published book burst "Patriarcha, or the Natural Power of Kings (The Patriarchate or the natural rights of the king)" by Robert Filmer in, already 30 years had died earlier. The content, however, was explosive to the Whigs, as it justified absolutism as the most natural form of government in the world since its creation and called upon subjects to silent submission. Sidney, who had written for his own purposes as well as for the Whigs pamphlets, felt so challenged by this book that he resumed his stalled work "Reflections on Forms of Government". Step by step he refuted Robert Filmer and used the topics to express his own views. Work on this work would drag on until his untimely death. Even the philosopher John Locke felt compelled to go into "Patriarcha" in detail for years after Sidney .

France's role in English politics

During this time, but also well before that, there was a third person who eagerly and successfully stirred up the fire on both sides in England. It was Louis XIV, King of France, who through his French ambassador at the English court Paul Barillion sent money to both sides and set up intrigues. In his three attempts to conquer the Netherlands, Louis XIV wanted to prevent an overpowering European alliance against France in this way. He benefited from the fact that Charles II could not raise taxes without the consent of his parliament and was therefore susceptible to French wishes. However, France was hated by the English. It had driven England from the European continent two hundred years earlier in the Hundred Years War . It had staged a bloody massacre among its Protestants, the so-called Huguenots , on Bartholomew's Night in 1572 . Louis XIV had also chased the last surviving Huguenots out of France, which was now exclusively Catholic and was regarded by the English as the refuge of a Catholic conspiracy that was only waiting for an opportunity to bloody through the Catholic Counter-Reformation in England. Charles II had therefore asked his then Chancellor of the Exchequer, the Earl of Danby, to conduct secret negotiations with France in 1678 in order to receive three times the previous annual support from France, the so-called subsidies , namely now £ 300,000 .

The Earl of Danby was just as hated to Louis XIV as the English Whigs - Louis XIV. Because he had always worked against France, the Whigs because he was not only a conservative, staunch monarchist, but also used his office to use his influence and wealth and to pursue all religions on both sides of the Anglican Church. Half a year later, the French ambassador Paul Barillion briefed Ralph Montagu and Algernon Sidney of the earl's English secret negotiations with France. Sidney then took on the task of disseminating the information about his cousin and nephews in the Whigs' party, while Montagu published it in newspapers and elsewhere, sparking a storm of indignation that brought the king to the Tower for his Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Earl of Danby of London brought. Algernon Sidney received Barillion money only twice in total. His honor has been questioned by some on the matter, not least Sir Winston Churchill . In Sidney's defense, however, it must be said that he only accepted the money if the obligations associated with it were consistent with his convictions.

The fourth parliament

On April 15, 1680, when Parliament was due to meet, Charles II postponed it again. This was repeated five more times until he had to bow to the pressure. The anti-Catholic mood had not died down, as Charles II had hoped. The Earl of Shaftesbury knew how to keep them at their peak. Further suspicions and even more daring allegations had been added. On October 29, 1680, the House of Commons unanimously passed a note in which it declared its allegiance to the King, but suggested, in the interests of the country and the Protestant faith, to investigate and prosecute all the findings and evidence of a Papist conspiracy so far collected by the House of Commons punish. The king took the note personally the next day and one day later promised to forward the documents to a committee formed in the House of Lords for careful examination. The lower house, becoming more radical from election to election, began on November 2nd to exclude Charles II's Catholic brother, the Duke of York , from the line of succession. In a so-called Bill of Exclusion , which was passed by the House of Commons on November 8, 1680, his banishment from England was demanded. His return or political activity abroad with the aim of becoming King of England should be punished as high treason . Charles II pretended to be willing to compromise and sent his brother Jacob, also for his safety, first to Brussels and later to Scotland , which was still independent at the time. The House of Lords rejected the Bill of Exclusion on October 15 with a narrow majority .

The House of Commons next dealt with the case of the five Catholic Lords who had been in the Tower of London since late October 1679 and who were charged with participating in the Popish Plot . The oldest among them was William Howard , Lord Stafford. Some sources report that he was certain of his innocence and pressed for a speedy trial. Other sources, however, claim that he was decrepit and threatened to die before the trial. In any case, he was solemnly tried in the House of Lords, chaired by Sir William Jones, which lasted from November 30th to December 7th. By 55 votes to 31, Lord Stafford was found guilty of the Popish Plot and sentenced to death by hanging and quartering. The king exercised his sovereignty and converted the sentence into death by the ax, whereupon a dispute arose between the House of Commons and the king over the manner of carrying out the death sentence. On December 23, the House of Commons finally agreed to have Lord Stafford executed by the ax only. At the age of 66, Lord Stafford was beheaded on December 29, 1680 on Tower Hill.

On January 4, 1681, Charles II also rejected the Bill of Exclusion passed by the House of Commons , whereupon the tone tightened in the House of Commons on January 7. Four members close to the king, including Lord Halifax, were accused of having incorrectly advised the king to reject the Bill of Exclusion , to be supporters of the Catholic Counter-Reformation and thus a danger to the king and kingdom. The next day in the House of Commons seemed like an ordinary day. January 10, however, began with a sharp resolution by the House of Commons, which declared any adjournment of the House of Commons as high treason against the King, Kingdom and Protestantism and declared every supporter of it as supporters of France and recipient of French bribes. The king's brother was held responsible in a resolution of the House of Commons that his rival in the line of succession, the Duke of Monmouth, had had to leave the House of Lords. Another resolution declared the great fire in London of 1666 to be the work of Catholic counter-reformers . Charles II then asserted his sovereign rights and adjourned the House of Commons in order to dissolve it again on January 18, 1681.

Political cooperation in one's own family clan

The fifth parliament

Charles II completely changed his strategy. He no longer supported the Dissenters to split the Anglican Church, but now the Tories, who had always been loyal to the king. He called the next parliament for March 21st in Oxford , which was quieter than London and a stronghold of the Tories . He made the parliamentarians an obligation to appear completely unarmed.

Algernon Sidney, with the help of William Penn, again ran for the parliamentary seats of Amersham and Bramber. His youngest brother Henry no longer ran for Bramber and was again the English ambassador to The Hague. The election in Amersham took place on January 29th, which Roger Hill won with 40 and Algernon Sidney with 37 votes. On the other hand, Sidney lost the election in Bramber to the local gentry.

The House of Commons, to which most of the Whigs nevertheless appeared armed for their own safety, met on March 21, 1681. At the opening, Charles II declared in his speech that Parliament should for the time being ignore the question of the succession to the throne, otherwise it would dissolve it immediately. On March 24, both Algernon Sidney and Sir Robert Hill filed petitions about the Amersham election , which in turn were forwarded to the Election Privileges Committee for comment . The impeachment and indictment proceedings against Lord Danby revived and were sent to the House of Lords. When, on March 28, the House of Commons wanted to pass a bill again, contrary to the warning, in which the Duke of York was to be excluded from the line of succession, Charles II immediately dissolved Parliament.

In a published statement, the king justified the dissolution of the last two parliaments and indicated that he intended to rule without parliaments in the future. The Whigs' response came in the "Just and simple defense of the proceedings in the last two parliaments," which the Anglican Bishop called "one of the best-written papers of the time," and which was written by none other than Algernon Sidney.

Charles II used the fact that some Whigs had appeared armed at Oxford as an excuse to have them arrested and ruthlessly pursued. The Whigs so accused were acquitted in court, but some were intimidated.

In order to manipulate the allocation of public offices in city administrations and parliamentary elections, he had the city's charter submitted to him. In cities whose cards had expired or could no longer be found, he withdrew them and had his own issued. By 1685, 56 licensees had been exchanged in this way.

William Penn and Lord Howard of Escrick

In March 1681, Charles II had already transferred English land in North America to William Penn and thus settled an old debt of £ 15,000 that William Penn had inherited from his father. In honor of his father, William Penn named this country Pennsylvania and worked on a draft constitution which he discussed with Algernon Sidney. In October 1681, Algernon Sidney found Penn's Frame of Government to be "worse than the Turks" and "not worth enduring or living under" . William Penn was deeply offended and the friendship broke over it.

Algernon Sidney helped another friend in need. William Lord Howard of Escrick was thrown into the debt tower in 1681 because he could not pay his debts. Algernon Sidney put the money in front of him to be released. Lord Howard of Escrick, like Sidney, had been a member of the rump Parliament in the Commonwealth . His reputation wasn't entirely perfect. He was the only member of parliament who was expelled from parliament for corruption. In 1679, Lord Howard of Escrick was able to produce papers entitling him to join the House of Lords. It was Lord Howard of Escrick who introduced Algernon Sidney to the possible heir to the throne, Duke of Monmouth. Algernon Sidney behaved rather dismissively. As a Republican, he was suspicious of any heir to the throne.

Whig persecutions

In July 1681, Charles II continued his repressive measures and had Lord Shaftesbury thrown into the Tower of London. A hastily constructed charge of treason did not stand up to scrutiny in the trial of Lord Shaftesbury on November 24, 1681. He was released.

The national hysteria surrounding the Popish Plot began to subside and the mood turned against the Whigs. Without Parliament, the Whigs were deprived of their platform, and there was no hope that it would ever be convened again under the reign of Charles II. The Whigs were unwilling to surrender their power and influence without a fight. In order to escape the persecution of Charles II, they met in secret and discussed the difficult political situation. Rumors of conspiracies and subversions made the rounds.

Rye House Conspiracy

Some of this group met in 1682 at Rye House in Hoddesdon , Hertfordshire . It was a day's march southeast of London and belonged to Richard Rumbold, known as the Republican. According to their plan, a force of a hundred armed men would hide on the premises of the house. They were supposed to ambush the king and his brother on their way home when they returned to London from the annual Newmarket horse race and murder both of them. According to the Pitaval , Lord Shaftesbury did not want to wait that long and instead started a riot in London. However, when he believed his plans had been discovered prematurely, he fled to the Netherlands in late 1682.

The Rye House conspirators continued their project and expected the ride of the king and his brother to London on April 1, 1683. In Newmarket, however, a great fire broke out on March 22, 1683, which destroyed half the city. The races were canceled and the King and Duke returned to London early. The Rye House conspiracy had failed.

Already at the end of April Algernon Sidney received the tip from the Earl of Clare that his arrest was inevitable. On June 12, 1683, a co-conspirator, Josiah Keeling, did not withstand the pressure that the conspiracy could be exposed and betrayed it. Arrest warrants against Attorney West and Richard Rumbold were issued on June 20th. A few days later, both of them presented themselves in the hope of receiving discounts as key witnesses . Other co-conspirators and the Duke of Monmouth fled abroad. That was the reason to write out arrest warrants for high treason over the next few days and to throw the suspects in the Tower of London . The first ran on Algernon Sidney on June 25th, Lord Russell on June 26th, Lord Hampden and Lord Howard of Escrick on July 9th, and Lord Essex on July 10th. Algernon Sidney and Lord Russell refused to flee.

arrest

“In mid-June, the city was full of rumors of a conspiracy that was betrayed by Keeling and a little later by West. Some people fled. […] My name could be heard in every coffeehouse, and various messages were passed to me that I should certainly be arrested too […], but knew no reason why I should hide and decided not to to do [...] although early in the morning of June 26th I was told that the Duke of Monmouth was in hiding and Colonel Rumsey had surrendered. That bothered me little, so that I spent the mornings studying or chatting with friends who had come just to see me. And while I was at table a messenger came and arrested me in the king's name. "

Lord Howard of Escrick tried to avoid arrest by hiding in the fireplace. He was discovered and thrown into the Tower of London. Algernon Sidney's cousin, Lord Essex, came to the Tower on July 12, 1683 and was found dead in his cell the next morning with his throat cut. On the same day the trial of Lord Russell for high treason began under the presidency of Judge Sir Francis Pemberton. Rumsey and West testified that Lord Russell had attended two meetings. The actual main witness was William Lord Howard of Escrick, who could only report this from hearsay, as Lord Russell pointed out. Lord Russell was sentenced to death by hanging and subsequent quartering for high treason on July 14, 1683. The king softened the sentence by death with the ax. Several attempts to obtain a pardon from the king were unsuccessful. On July 21, 1683, Lord Russell was executed.

The process

The process against Algernon Sidney turned out to be difficult. At the end of July, Sidney was brought before the King and State Council and interrogated. He stated that he knew how to defend himself well if they had any evidence against him, but that he was unwilling to support any suspicions of theirs by testifying. The interrogation was very brief that way. More weeks passed, and Algernon Sidney thought this was a good sign, suggesting that the evidence so far was inadequate for trial. During his time in prison, his brother Henry Sidney visited him, who "treated him with great respect and prudence and brought good news from all people". His brother, the Earl of Leicester, with whom he had great differences over an annual payment of £ 2,000 , did not visit him, but sent him £ 1,000 as a deposit because he could no longer bear the scolding for it. In the last week of October, Charles II pushed the matter forward to bring Sidney to justice. The working paper “Mr. Sheperd's Handwriting Review " October 21st was an early warning. It compared the handwriting of Algernon Sidney with that of a paper that was found during a search of his cell and belonged to Sidney's "reflections" . On November 7, 1683 he was tried under the chairmanship of Lord Chief Justice George Jeffreys in the Kings Bench Court. Jeffreys was notorious for serving the king, bowing the law and pressuring the jury. The exclusion parliament had severely reprimanded his behavior in response to a complaint. At the trial of Lord Russell he was noticeable for his indomitable toughness and was promoted to chief justice on September 29, while Sir Francis Pemberton , who showed respect for Lord Russell, was removed from office. Sidney criticized the composition of the jury, which had been created illegally through manipulation , and he complained that he had been denied a copy of the indictment.

The only witness who testified against Sidney was the Lord Howard of Escrick whom Sidney had freed from the debt tower. Sidney cited numerous witnesses who questioned the integrity of Lord Howard of Escrick. According to the law, at least two witnesses should have sworn the open attempt at high treason . Jeffreys, however, allowed the negotiations to continue without citing a second witness. Sidney raised this issue several times, but each time was severely reprimanded and received evasive answers. Distraught and confused, Sidney lost the initiative and left the negotiations to Jeffreys, who at the end cited the paper found during the search as a makeshift second witness . The paper found contained only considerations about forms of government of a general nature. Jeffreys now tried to deduce high treason from some passages of the paper and, with his newly established legal principle "Scribere est agere ", to evaluate this as an "open act of high treason" . In legal history this was something completely new in several ways. Among other things, it was new that an author should be sentenced for a work that was not intended for printing. On November 21, 1683, Sidney was found guilty of high treason after an hour and a half deliberation with the jury and then sentenced to death by hanging and then quartered .

The trial and the verdict caused a stir and caused waves of indignation, so that Charles II decided to wait until the excitement subsided before the execution . The Duke of Monmouth, the illegitimate son of Charles II, emerged from hiding and was reconciled with his father. On November 25 put Lord Halifax a petition one with the king at the Sidney pointed to the irregularities during the procedure and asked for re-examination of his accusation. But the Duke of York, who dominated the State Council, had already decided Sidney's fate, and Jeffreys furiously declared that either he or Sidney would die. On November 26th, Sidney was brought before the Revision Committee , in which Jeffreys was also represented. From his point of view, Sidney could hardly explain the procedural errors, since he was repeatedly interrupted by Jeffreys or withdrawn from him. “I have to call on God and the world. I was not heard, ” was one of his last submissions before his revision was rejected and he was returned to the Tower. A second petition to Charles II was also rejected. Algernon Sidney began in his cell to write his "Apology - In the day of his death" .

execution

It took a long hesitation to sign the file of Algernon Sidney's execution, and the execution by the ax, which omitted the other atrocities, was softened. On December 7, 1683, the sheriffs took him out of his cell and led him to a scaffold that had been erected on Tower Hill and was covered with black cloth instead of straw. When he reached the top of the scaffold calmly and composed, he said: “I have made my peace with God and have nothing to say to people; but this paper is about what I have to say, ” and gave the paper to the sheriff. Sidney took off his hat and coat and prayed briefly. He gave his executioner a tip and put his head calmly on the scaffold. When asked whether he would like to get up and stand up again, he replied laconically: “Not until the day of judgment . Strike . ” His head fell with one stroke and was shown to the silent crowd around the scaffold before his remains were handed over to his youngest brother's two servants in a black coffin at the direction of the State Secretary. The next day he was buried with his ancestors at Penshurst.

| Algernon Sidney fills this tomb | Algernon Sidney animates this grave | |

| To atheist, for disclaiming Rome | As an atheist, he rejected Rome | |

| A Rebel bold, for striving still. | An intrepid rebel who in all cases | |

| To keep the law above the will | It dared to put the law above the will | |

| Crimes, damned by church-government! | An offense for church and government | |

| Ah! whither must his ghost be sent? | Oh! Where will his mind go now? | |

| Of heaven it cannot despair, | In heaven he doesn't need to try | |

| If holy Pope be turnkey there: | The holy Pope is up there behind the doors | |

| And hell ne'er it will entertain | He does not want to be admitted to hell either | |

| For there is all tyrannic reign! | It is tyranny that pervades there | |

| Where goes it then? Where 't ought to go | Where is he going then? Where should he go | |

| Where pope nor devil have to do | Where there is neither Pope nor devil | |

| Author unknown | ||

| Poem widely used after the execution |

Development of England after the execution

The condemnation of Sidney was widely considered to be one of the cruellest and most tyrannical acts of the reign of Charles II. Even the trials of Henry Vane , Lord Russell and Hampden - insofar as they can be compared - did not attain the cold-bloodedness and malevolence of Sydney. Contrary to what Charles II had hoped, Algernon Sidney and Lord William did not fall into oblivion, but became folk heroes who innocently gave their lives. A few months later, a report on Sidney's trial was printed in 1684. However, this previously ran through the hands of Jeffreys, who made some changes and deletions.

Another year later, Charles II died of urine poisoning ( uremia ). He was followed to the throne by his brother James II, who made George Jeffreys his Lord Chancellor and had the Duke of Monmouth executed after the latter rose against him. Across the country, Jacob pursued pro-Catholic and anti-Protestant policies. In 1688, after only three years in office, Jacob II was driven out by the Glorious Revolution of 1688, which elevated the Protestant William of Orange and his wife Maria II, a daughter of Jacob, to the royal throne. The first official act of Wilhelm III. was to fully rehabilitate Algernon Sidney and Lord William Russell with all honors.

Sidney's work, Considerations on Forms of Government , appeared posthumously in 1698 in several editions (among others. Ed. J. Toland 1698, original title: "Discourses concerning Governments") and also influenced the American Declaration of Independence of 1776. In 1772, almost 90 years after his death, Sidney fell into the Headlines when the historian Sir John Darymple discovered in his work "Memoirs of Great Britain and Ireland" that Sidney had received funds from the French side. Darymple relied on papers found in the depot des Affaires Etrangères in Versailles . In the last decade of the 18th century, a few years after the French Revolution , the general interest in Algernon Sidney was so great that his grave was opened and his remains were found to be very well preserved.

character

In the mirror of his contemporaries

During the war, an eyewitness described Sidney as brave. His many wounds were "the true badge of his honor." . Whitelock, Member of Parliament, found the following words for Sidney in 1659: "I know only too well his overriding character and its extent" . Charles II presented Sidney to the French minister Colbert as a man "who cannot be far from England, where his dangerous feelings paired with great ability and courage can do much harm" . The French ambassador to England Barillion reported to Louis XIV about Sidney: “Mr. Algernon Sidney is a man of great beliefs and very far-reaching plans for a republic. He is the man in England who I think has the greatest understanding of politics; he has significant ties with the rest of the Republican Party; and in my opinion no one is more capable of doing (us) a service. " John Evelyn wrote in 1683: " A man of great courage, great sanity and great ability, which he showed at his trial and in his execution ". And the Archbishop Dr. Gilbert Burnett characterized Sidney: “He was a man of particularly extraordinary courage; a steadfast man to the point of tenacity; sincere, but of a rough and impetuous disposition that could not stand contradiction. [...] He stood by all republican principles and as such was an opponent of everything that looked like a monarchy that made him slide into deep opposition to Cromwell, when he made himself lord protector. He had studied the forms of government of the past in all their ramifications in a way that I do not know of any other person. "

Anecdotes

Dissolution of parliament in 1653

On April 20, 1653, Oliver Cromwell surrounded the House of Commons with the intention of finally dissolving it. Most MPs bowed to the pressure. The Speaker of Parliament and Sidney, who sat to his right, resisted. The speaker was forcibly dragged away by his robe. It was Sidney's turn. He did not comply with two requests to leave. Twice Oliver Cromwell had to order his General Harrisson: "Take him away." It was only when Sidney had been grabbed by the shoulder left and right and serious intentions were made that he reluctantly went outside.

Execution of the King

An English minister who was in Copenhagen in 1659 said to Sidney: “I think you were neither one of the judges of the last king nor guilty of his death,” to which Sidney replied: “Guilty, what do you mean by this debt? Why wasn't it just the most just and courageous act ever taken in England or anywhere else? "

Desirability of Louis XIV.

While hunting together, the horse of Algernon Sidney caught the attention of Louis XIV, and he had him ask about the price of the horse. To Louis XIV's surprise, however, Sidney refuses. Louis XIV, who is not used to contradictions, sets a sum and wants to confiscate the horse. Upon hearing this, Sidney draws his pistol and shoots his horse with the words: “This horse was born a free creature, served a free man, and is not to be chastened by the king's slaves. "

meaning

It is not easy to describe Algernon Sidney's ideas. He influenced the ideas of the American revolutionary theorists. He is less radical than Niccolò Machiavelli , less individualistic than John Locke , less cynical than Bernard Mandeville , more liberal and more democratic than Plato and Aristotle . Freedom and righteousness, "liberty and virtue" , were important values in his conception of an ideal government. Along with Niccolò Machiavelli and Adam Ferguson, Algernon Sidney is one of the few political philosophers who endeavored to think of a pluralistic and conflict-ridden republic.

American constitution

Sidney's influence on the North American colonies

John and Samuel Adams , George Mason , James Madison, and Benjamin Franklin all recognized Sidney's influence on American politics. A group from Virginia founded a university in 1776 and named it in honor of Algernon Sidney and Hampden Hampden-Sydney College. And in 1825, as the founder of the University of Virginia , Thomas Jefferson made the following statement:

“It is determined that the Assembly here present believes that, for the general principles of freedom and human rights, both in nature and in society, the doctrines of Locke in his work, On True Nature, Extent and the purpose of bourgeois government 'and the doctrines of Sidney in His Discourses on Government are considered by our fellow citizens and by the United States to be universal. "

Sidney's influence endured. Massachusetts adopted its motto in 1775: "Ense petit placidam sub libertate quietem" . His most widely reproduced quote appeared in Benjamin Franklin 's Poor Richard's Almanack : "God helps those who help themselves . " American opponents of slavery such as William Lloyd Garrison quoted another line: “What is wrong is not law; and what is not law should not be obeyed. ” One of the American Constitutional Fathers gave Algernon Sidney the title of Patriot of All .

Sidney's popularity fell sharply in the 19th century. The considerations were out of print in America between 1805 and 1979. His compatriots remembered his collaboration with foreign leaders; Winston Churchill, however, called him invincible . The Catholic Lord Acton called it "absurd to trace a political line back to Algernon Sidney, who was an agent paid by the French king."

philosophy

Sidney and Filmer's "Patriarcha"

Filmer's "Patriarcha" in the 1680 edition read by Algernon Sidney was divided into three chapters:

- From the first kings who were heads of their families

- It is against nature when the people rule or choose their ruler

- The positive rights do not violate the natural and paternal power of kings

Algernon Sidney's answer is accordingly divided into three chapters, which have no headings. He argues as follows:

- Paternal violence is fundamentally different from political violence.

- The people elect the government by virtue of their natural right to freedom , and such a government, with its strong popular participation, is the best.

- Kings submit to the law, which in England means parliament .

Sidney took filmmaker argument sarcastically as follows together: God "is responsible for ensuring that some are born with a crown on his head and all with the saddle of the Kings on the back" . Sidney, Tyrell and John Locke, on the other hand, believe that "people are naturally free" . Freedom is "a gift from God and nature" . However, “people cannot live in the freedom God has given them. The freedom of the individual is restricted by the freedom of the other; and because all are equal, no one gives way to the other unless it is everyone's choice. This is the basis of all righteous rule . ” Not birth but free choice determines the rightful rulers of men.

But freedom is an ambiguous term for Sidney. On the one hand, it means the complete absence of rule: “Freedom is the exclusive independence from the will of another.” But “freedom without rule” is, however, not desirable, “it contradicts every government and the good that people want for themselves, their children and friends ” .

Sidney alludes to the different understandings of freedom when he speaks of the fact that "he who is guided by his passions and madnesses is a slave to his lusts and vices" . Following Aristotle , Sidney calls people who are incapable of self-control "slaves of nature" . In this sense, it is freedom that follows reason, not passion. Freedom in the broader sense of reason means a certain amount of self-control . Freedom requires virtue to support it , and more importantly, people need virtues if they are to become masters of themselves. In order to attain pure freedom, a government will reward virtue and punish vice . "When public security is ensured, freedom and property are protected, justice is exercised, virtues are favored, vices are suppressed, and the true interests of the nation are achieved, then the government's mission is accomplished," wrote Sidney.

Of course, it is in the interests of the government and it is common sense to protect people in their natural freedom as much as necessary. Under normal circumstances the government provides for the families and their subsistence, but the people should be left to their own devices. The government therefore protects the people's right to “land, prosperity , life and freedom” . The government is formed when the people agree to give up their natural freedom. The inhabitants of a state undertake to obey their rulers on the condition that they rule until the goal for which the government was formed has been achieved. Each government should therefore be limited in time until this goal is achieved. The role of government is determined by the law of nature , which for Sidney means something simple: The laws of governance arise from common sense, with which one ponders the nature of man. From Sidney's point of view, the laws of nature teach us, among other things, that human beings are born free, that fathers must be obeyed, that injuries are avoided and, if they do happen, punished, that the best suited should rule and that the individual is not the slave his passions should be. “Nothing but the mere and certain dictation of reason can be applied in a general way to all human beings as the law of their nature, and those who best understand this dictate will ensure the prosperity of all human beings and their descendants obeyed all regulations equally. ” Under a just government that relies on the consent of the governed and whose duties are regulated by natural law and the treaty, the people also have the right to overthrow the government if it violates the rules. This right to revolution is the most controversial part of Sidney's theory of the state. It was ridiculed at his trial and led directly to his sentencing and execution.

Since all human beings are subject to passions and are prone to self-interest, the well-being of the people is best protected by government law. In a passage that John Adams liked to quote, Sidney says that the law is “the avoidance of desires and fears, cravings and anger. This dispassionate thinking and verbal reason show a measure of divine perfection ” . In Sidney's strict interpretation, the term "law" rules out that this serves the own interests of the rulers. Because "everything that is not just is not a law, and what is not a law should not be obeyed either" .

Not surprisingly, of the various forms of government, the monarchy comes last for Sidney. However, it is not always clear which form of government is the best according to its principles. It seems that the people themselves may agree to whatever form of government they enjoy. In any case, it is clear that in his remarks, Sidney preferred a partially to fully democratic government. It must be in harmony with the freedom that man has by nature and which offers him the best opportunities to receive the equivalent value for his merits. Prudence ensures that political constitutions adapt to a certain extent to the individual circumstances of a people. Rome was so corrupt that "it the best man who was found was impossible to establish freedom in the city again" . But Sidney was no relativist; the principles of governance have timeless validity for him, only their applications differ from time to time. Sidney was a staunch opponent of hereditary monarchies, because they not only restrict freedom, but also because they do not adequately appreciate the personal merits of the ruler. Unlike other thinkers, who also based their political ideas on the natural freedom of man, Sidney adopted the principle from Plato and Aristotle that the more deserving should rule. “Detur digniori [give it to the more worthy] is the voice of nature; all of their mostly sacred laws were perverted if that principle was not obeyed by the ordinances of governments throughout [history of] mankind ” . In agreement with Aristotle, Sidney even took the position that a godlike and virtuous prince who represented the common good had the right to rule even without the consent of the governed. "If such a man is found, he is by nature king" . But continuing to follow Aristotle, Sidney goes on to say that no such being can be found among imperfect humans. This makes the otherwise aristocratic thinking Aristotle briefly appear as a teacher of republicanism.

Sidney and Locke in comparison

John Locke wrote "On Government" at the same time as Sidney wrote his "Reflections on Government" . Although Locke's work is more widely known, a comparison between the two works is fruitful.

While some historians have attributed Locke to the emerging civil or liberal tradition of natural rights, Sidney is said to be more of the tradition of "classical republicanism" derived from Machiavelli and his predecessors. Other historians note that Sidney does not stand up to this pattern comparison and that Sidney is even more of a man of the natural rights of the social contract than Locke. Both stand for an electoral government. Both claim that natural freedom is shaped by natural law . Both are in favor of limited government and the right of the people to oppose unjust government. Both are ardent representatives of freedom. Sidney and Locke are as much " Republicans " as they are " Liberals " .

Regardless of these similarities, there are differences that are significant. Sidney is closer to the Greek and Roman classics than Locke. It is characteristic that Sidney often leads the classics while Locke rarely does. However, most of the Greek and Roman philosophers are not true "classical republicans" in the sense of Niccolò Machiavelli . Your political ideas begin or end with the individual human being, who does not represent an isolated entity, but a being who, by virtue of its human nature, strives for a life that is in harmony with a purpose. What now follows are individual illustrations of the range of differences between Sidney and Locke.

While both advocate a government based on mutual consent, Sidney is just as insistent that the people of higher rank should rule, and he defends a people's government that puts in place such powerful people. For Sidney, as for the classical thinkers, one of the government's duties is to promote virtues and eliminate vices. This does not apply to Locke.

It is characteristic of Sidney that he never invokes a pre-civilizational "state of nature" , as Locke does, even when civilization reverts to a state of war. According to Locke, in this natural state man is in poverty , danger, or insecurity. It becomes political by subjugating nature, not by following it. Reason, according to Locke, is the means by which man subjugates and conquers nature by building a government and a capitalist industry. For Sidney, reason is already in human nature, as he keeps repeating. Sidney refers to the natural state of Thomas Hobbes - the war everyone against everyone - an " epidemic of madness" into which people fall back when the world is forsaken by God. Man is born free, but Sidney does not believe that it is natural for man to live without laws. Without adopting Aristotle's way of thinking , Sidney goes on to imagine humans as an inherently political, rational living being.

Sidney's law of nature goes beyond the reasons for self-preservation and includes various virtues that enable a reasonable life. This draft continues the tradition of natural law by leaning on the classical thinkers. Locke's doctrine of a law of nature breaks tradition by basing it on the fundamental rights to life and liberty of every individual. At the center of Locke's moral world is not man's destiny, but man himself or man's independence. On this point he follows Hobbes.

Sidney and Locke rate the trade very differently. For Locke, trade is of fundamental importance, as it enables man to escape the shortage of goods to which he would be at the mercy of an untamed nature. Sidney also sees the goal of any state policy in achieving prosperity , but only because it contributes to a nation's fighting power; otherwise, he rejects making money as a source of corruption .

Sidney never questions the father's right to rule over the family. Locke, on the other hand, speaks of respect, but not obedience to the father and mother . For Sidney, civil society is an association of fathers as heads of families. Locke's more radical individualism calls into question the traditional family, which is based on values other than natural factors such as masculinity or femininity.

All in all, Locke's thoughts, though expressed with great caution, are far more radical and modern in terms of their terms than Sidney's. Sidney's republicanism still adheres to an outlook on life that is recognizable in the classical and medieval tradition of political philosophy.

Sidney's ideas about representation and parliament

In “Considerations on Forms of Government” Sidney takes the view that the MPs elected to parliament do not represent the interests of their constituency, but those of their nation. The parliament is therefore not a composition of the sometimes conflicting individual interests of the constituencies, but a council of men who strive solely for the common good of the nation and should therefore be independent of the individual interests of their constituency. For Sidney, the nation is an indivisible whole. In addition, in his opinion, individual MPs are entitled to represent the interests of the nation externally and within the framework of parliamentary work. Thomas Hobbes and later Abbé Sieyès , William Blackstone , Edmund Burke and William Paley also share this view .

Quotes

The references refer to the considerations on forms of government published in Leipzig in 1793 with partially revised translation of quotations.

“Manus haec inimica tyrannis, Ense petit placidam sub libertate quietem.

This hand, an enemy of tyrants, calls for peaceful peace in freedom with the sword ”

"God helps those who help themselves."

"A liar must have a good memory."

“When vice and moral corruption rule, freedom cannot exist. But if virtue has the preponderance, then arbitrary violence cannot arise in the first place. "

"Freedom cannot be preserved if the people allow themselves to be bribed."

“Fruits are always of the same nature as the seeds and roots from which they come, and trees are known for the fruits that they bear: just as a person can only breed one person and cattle only cattle, the tree is primarily recognizable on the fruits. Just as a person begets only one person and cattle only one cattle, in the society of men a government is constituted on the basis of justice. "

gallery

Sidney's works

English

- Literature by and about Algernon Sidney

- Algernon Sidney: Court Maxims, Discussed and Refelled. unpublished

- Algernon Sidney: Discourses concerning government. London 1698 u. more often ; German, Leipzig 1794;

- Algernon Sidney: Discourses. ed. John Toland, 1698.

- Algernon Sidney: Discourses Concerning Government. the original heading God helps those who help themselves - God helps those who help themselves. wearing;

- Algernon Sidney: Apology in the Day of His Death.

- Algernon Sidney: The Administration and the Opposition. Addressed to the Citizens of New Hampshire. Concord, Jacob B. Moore, 1826.

- Algernon Sidney: Discourses Concerning Government. ed. Thomas G. West, Indianapolis 1996, ISBN 0-86597-142-0 .

- Algernon Sidney: Court Maxims ( Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought ). Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-521-46175-8 .

- Algernon Sidney: Discourses on Government. To Which is Added, An Account of the… Reprint, 3 volumes, The Lawbook Exchange, New York, 2002, ISBN 1-58477-209-3 .

German

- Algernon Sidney, Christian Daniel Ehrhard: Algernon Sidney's reflections on forms of government. Leipzig 1793, Weygand

literature

English

- George W. Meadley: Memoirs of Algernon Sidney . London, Cradock and Joy 1813.

- Alex. Charles Ewald: The Life and Times of the Hon. Algernon Sidney. 1622-1683 . 2 vols., Tinsley Brothers, London 1873.

- Gertrude M. Ireland Blackburne: Algernon Sidney. A review . Kegan Paul - Trench, London 1885.

- James R. Jones: The First Whigs. The Politics of the Exclusion Crisis 1678-1683 . Oxford University Press, London [u. a.] 1961.

- James Conniff: Reason and History in Early Whig Thought. The Case of Algernon Sidney . In: Journal of the History of Ideas. Volume 43, 1982, ISSN 0022-5037 , pp. 397-416.

- Blair Wordon: The Commonwealth Kidney of Algernon Sidney . In: The Journal of British Studies / The Historical Journal. Volume 24, 1985, No. 1, ISSN 0018-246X , pp. 1-40.

- JGA Pocock : England's Cato. The virtues and fortunes of Algernon Sidney . In: The Historical Journal. Volume 37, 1994, No. 4, ISSN 0018-246X , pp. 915-935.

- John Carswell: The porcupine. The life of Algernon Sidney . John Murray, London 1989, ISBN 0-7195-4684-2 .

- Jonathan Scott: Algernon Sidney and the Restoration Crisis. 1677-1683 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge [u. a.] 1991, ISBN 0-521-35291-6 .

- Alan Craig Houston: Algernon Sidney and the Republican Heritage in England and America . Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1991, ISBN 0-691-07860-2 .

- Scott A. Nelson: The Discourses of Algernon Sidney . Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press, Rutherford [et al. a.] 1993, ISBN 0-8386-3438-9 .

- George Van Santvoord: Life Of Algernon Sidney. With Sketches Of Some Of His Contemporaries And Extracts From His Correspondence And Political Writings . Gardners Books, Eastbourne 2007, ISBN 978-0-548-15105-1 .

German

- Sidney, 2) Algernon . In: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon . 6th edition. Volume 18, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1909, pp. 428–429 .

- Sidney, 2) Algernon . In: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon . 4th edition. Volume 14, Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1885–1892, p. 939.

- Christoph Martin Wieland : CM Wieland's Complete Works . Volumes 35-36. GJ Göschen, 1858, p. 38 ( full text (p. 38) in the Google book search).

Web links

English

- William F. Campbell: Professor Classical Republicans: Whigs and Tories. Louisiana State University

- Why did the Whigs fail with Charles II's exclusion from the throne?

- Sample chapter (PDF)

- Prepared, not given speech before his execution

- Algernon Sidney in the Online Library of Liberty

German

- Willibald Alexis : The new Pitaval. William Lord Russell in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Legal philosophy and understanding of the state in the 17th and 18th centuries

- Illustration by Georg Melchior Kraus Algernon Sidney in the German Mercury of 1778

- Understanding the representative form of government ( Memento of March 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

Documents

Individual evidence

- ↑ Life Of Algernon Sidney: With Sketches Of Some Of His Contemporaries And Extracts From His Correspondence And Political Writings. Kessinger Publishing , 2007, ISBN 978-1-4304-4449-7 , p. 22

- ↑ a b c d e Algernon Sidney: Discourses Concerning Government , ed. Thomas G. West, Indianapolis 1996, ISBN 0-86597-142-0 , p. 6.

- ^ A b Jonathan Scott: Algernon Sidney and the Restoration Crisis, 1677-1683. Cambridge University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-521-35291-6 , pp. 90 f.

- ↑ a b c George Van Santvord: Life Of Algernon Sidney: With Sketches Of Some Of His Contemporaries And Extracts From His Correspondence And Political Writings. Kessinger Publishing, 2007, ISBN 978-1-4304-4449-7 , p. 32.

- ↑ George Van Santvord: Life Of Algernon Sidney: With Sketches Of Some Of His Contemporaries And Extracts From His Correspondence And Political Writings. Kessinger Publishing, 2007, ISBN 978-1-4304-4449-7 , p. 132.

- ↑ George Van Santvord: Life Of Algernon Sidney: With Sketches Of Some Of His Contemporaries And Extracts From His Correspondence And Political Writings. Kessinger Publishing, 2007, ISBN 978-1-4304-4449-7 , p. 152.

- ↑ Chris Baker: Algernon Sidney: Forgotten Founding Father libertyhaven.com ( Memento of September 4, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) and George Van Santvord: Life Of Algernon Sidney: With Sketches Of Some Of His Contemporaries And Extracts From His Correspondence And Political Writings. Kessinger Publishing, 2007, ISBN 978-1-4304-4449-7 , p. 176.

- ↑ Algernon Sidney: Life, Memoirs, etc. of Algernon Sydney. DI Katon, London, 1794, p. 55.

- ↑ Algernon Sidney: Life, Memoirs, etc. of Algernon Sydney. DI Katon, London, 1794, p. 150.

- ↑ Sidney, Algernon . In: Encyclopædia Britannica . 11th edition. tape 25 : Shuválov - Subliminal Self . London 1911, p. 40 (English, full text [ Wikisource ]).

- ↑ Algernon Sidney Brief insight into family history and financial circumstances

- ↑ Jonathan Scott: Algernon Sidney and the Restoration Crisis, 1677-1683. Cambridge University Press, 1991, p. 100.

- ↑ Jonathan Scott: Algernon Sidney and the Restoration Crisis, 1677-1683. Cambridge University Press, 1991, pp. 161 f.

- ↑ Jonathan Scott: Algernon Sidney and the Restoration Crisis, 1677-1683. Cambridge University Press, 1991, p. 18.

- ^ Journal of the House of Commons , Volume 9: 1667-1687. 1802, p. 635.

- ↑ They are now in the Cambridge University Library - see Jonathan Scott: Algernon Sidney and the Restoration Crisis, 1677–1683. Cambridge University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-521-35291-6 , p. 21.

- ↑ Jan Bruners: British History 1625 to 1685. P. 35. (PDF; 299 kB)

- ^ Journal of the House of Commons , Volume 9: 1667-1687. 1802, p. 642 f.

- ^ Journal of the House of Lords. Volume 13: 1675-1681. 1771, pp. 665-671.

- ^ Journal of the House of Commons , Volume 9: 1667-1687. 1802, pp. 687-692.

- ^ Journal of the House of Commons , Volume 9: 1667-1687. 1802, p. 701 f.