Comic

Comic [ ˈkɒmɪk ] is a term for the representation of a process or a story in a sequence of images. Usually the pictures are drawn and combined with text. The comic medium combines aspects of literature and the visual arts , with the comic being an independent art form and a corresponding field of research. There are also similarities with the film . “Sequential art” is also used as a genre-neutral term, while regional forms of comics are sometimes referred to with their own terms such as Manga or Manhwa .

Characteristics and techniques typical of comics, but which do not necessarily have to be used, are speech and thought bubbles, panels and onomatopoeia . These are also used in other media, especially when text and the sequence of images are combined, as in picture books and illustrated stories, in caricatures or cartoons . The demarcation to these closely related arts is blurred.

definition

In the 1990s, a definition of comics established itself as an independent form of communication independent of content, target group and implementation. In 1993, Scott McCloud defined comics as " pictorial or other signs arranged in spatial sequences that convey information and / or create an aesthetic effect on the viewer". He takes up Will Eisner's definition of comics as sequential art. In the German-speaking world, the medium defined by McCloud is also generally referred to as “picture history” and the comic has been its modern form since the 19th century. Dietrich Grünewald speaks of a superordinate "principle of picture history", the modern form of which is the comic with the design elements developed around 1900. Andreas Platthaus calls the comic the “most advanced form” in visual history. As with McCloud, the comic or picture story is defined as an independent medium that tells through image sequences. Eckart Sackmann defines the comic with direct reference to McCloud as “a narrative in at least two still pictures”. However, with some definitions it is unclear whether individual, narrative images that depict an event without showing the before and after are also included in the comic. Even a representation that formally consists of only one picture can contain several sequences - for example with several speech balloons or more than one action in one picture that cannot take place at the same time.

Earlier definitions of comics related, among other things, to formal aspects such as continuation as short picture strips or appearing in booklet form, a framed sequence of pictures and the use of speech bubbles. In addition, content-related criteria were used, such as a constant and non-aging personal inventory or the orientation towards a young target group, or the design in style and technology. These definitions as well as the understanding of comics as an exclusive mass medium or mass drawing goods were rejected in favor of the current definition in the 1990s at the latest.

Illustrations , caricatures or cartoons can also be comics or part of such. The delimitation, especially with single images, remains blurred. In the case of picture books and illustrated stories, in contrast to comics, the images only play a supporting role in conveying the action. However, the transition is fluid here too.

Etymology and conceptual history

The term comic comes from English , where as an adjective it generally means "funny", "funny", "droll". In the 18th century, "Comic Print" referred to joke drawings and thus appeared for the first time in the field of today's importance. In the 19th century, the adjective was used as part of the name for magazines that contained picture jokes, picture history and texts. By the 20th century, the term "comic strip" came up for appearing in newspapers, short picture stories into strips (Engl. Strip ) tell arranged images. In the decades that followed, the meaning of the word expanded to include the newly created forms of comics and completely broke away from the meaning of the adjective "comic". After the Second World War , the term also came to Europe and initially competed in Germany with “Bildgeschichte”, which was supposed to distinguish higher quality German comic works from licensed foreign comics. Finally, “Comic” also caught on in the German-speaking world.

Due to their shape, comic strips also shaped the French term “Bande dessinée” and the Chinese “Lien-Huan Hua” (chain pictures). The frequently used means of the speech bubble led to the Italian term Fumetti ("puff of smoke") for comics. In Japan, " Manga " ( 漫画 , "spontaneous image") is used, which originally referred to sketchy woodcuts.

history

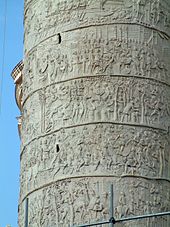

The origins of the comic go back to antiquity . In the tomb of Menna, for example, from 3400 years ago, there are paintings depicting the harvest and processing of grain in a sequence of images. This sequence of images in particular reads in a zigzag from bottom to top. In the scene of the weighing of the heart in the Hunefer papyrus (approx. 1300 BC) the sequences of images are supplemented with dialogue text. However, Egyptian hieroglyphs themselves do not represent a pre-form of the comic, as these, despite their imagery for sounds, do not represent objects. Other examples of early forms of storytelling are the Trajan Column and Japanese ink paintings .

In America, narratives were reproduced in sequential image sequences just as early. An example of this art was discovered by Hernán Cortés in 1519 and tells of the life of a pre-Columbian ruler in 1049. The images are supplemented with explanatory characters. In Europe, the Bayeux Tapestry was created in France in the High Middle Ages and depicts the conquest of England by the Normans in 1066. Here, too, text and images are combined. Many representations in churches of this time, such as altarpieces or windows, have a comic-like character. At that time they conveyed stories to particularly illiterate social classes. The Vienna Genesis , a Byzantine manuscript from the 6th century, is one of these works. In many cases, the speech bubble in the form of banners is anticipated. In Japan, monks have been drawing sequences of pictures on rolls of paper since the 12th century, often with Shinto motifs. Booklets with comic or folk stories were distributed well into the 19th century. At the same time, the term manga , which today stands for comics, was coined in Japan . The work of the woodcut artist Katsushika Hokusai is best known from this period .

After the invention of the printing press in Europe, prints of stories of martyrs found widespread use among the population. Later the drawings became finer and the text was left out again, as in the common prints. So with William Hogarth , who among other things created A Harlot's Progress . These stories consisted of a few pictures that were hung in a row in galleries and later sold together as an engraving. The pictures were rich in detail and the contents of the stories were socially critical. Friedrich Schiller , too, created a picture story with Avantures of the New Telemach , which again used text and integrated it into scrolls as in the Middle Ages.

From the end of the 18th century many forms of comics were found in British jokes and caricature journals such as Punch , mostly short and focused on humor. The term comic originates from this time . McCloud describes Rodolphe Töpffer as the father of modern comics . He used panel frames and stylized, cartoon-like drawings and combined text and images for the first time in the mid-19th century . The stories had a cheerful, satirical character and were also noted by Johann Wolfgang Goethe with the words If he chose a less frivolous subject in the future and pulled himself together a little more, he would do things that were beyond all concepts . The picture sheets popular in the 19th century also often contained comics, including Wilhelm Busch's picture stories .

In the United States, in the late 19th century, short comic strips were published in newspapers that usually took up half a page and were already called comics . Yellow Kid by Richard Felton Outcault from 1896 is considered by some to be the first modern comic, but does not yet have a narrative moment. Rudolph Dirks brought one such in with his Wilhelm Busch-inspired series The Katzenjammer Kids in 1897. Another important comic of that time was Ally Sloper's Half Holiday by Charles H. Ross Andreas Platthaus sees George Herriman's comic strip Krazy Kat, which appeared in 1913, as a greater revolution than in previous works, because Herriman created the comic's own genre Funny Animal and developed new ones Stylistic devices. In Europe, too, there were caricature magazines at the beginning of the 20th century, but there were hardly any sequential comics. Caricature magazines were also established in Japan and the speech bubble stylistic device was adopted from America. Kitazawa Rakuten and Okamoto Ippei are considered to be the first professional Japanese illustrators to create comic strips in Japan instead of the caricatures that were already widespread.

In Europe, another form of comics developed in France and Belgium, the comic book , in which longer stories were printed in continuation. An important representative was Hergé , who created Tintin in 1929 and established the Ligne claire style . In America too, longer stories were soon published in supplements in the Sunday papers. Hal Foster's Tarzan made this type of publication popular. Prince Eisenherz followed in 1937, and for the first time in a long time the integration of texts and speech bubbles was dispensed with. Similarly, the characters of Walt Disney developed from gag strips to longer adventure stories. This happened to Mickey Mouse in the 1930s by Floyd Gottfredson , and to Donald Duck in the 1940s by Carl Barks . After the invention of Superman by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster in 1938, a superhero boom broke out in the USA . This focused on the target group of children and young people and helped the comic book to break through.

During the Second World War , especially in America and Japan, comics were ideologized. With the rise of superhero comics in the USA, it increasingly happened that the work of the author and the illustrator were separated. This was done primarily to make work on the notebooks more efficient. In America, the illustrator Jack Kirby and the author Stan Lee were among the artists who shaped the Golden Age of superheroes in the 1940s and the Silver Age in the 1960s. In the 1950s, the Comics Code led to the closure of many small publishers and the dominance of superhero comics in the United States. In Europe, too, the division of labor became more frequent.

In the GDR, the term comic was considered too western. So the idea arose in the GDR to create something of their own in the tradition of Wilhelm Busch and Heinrich Zille , which could be countered with the “trash” from the West. In 1955, Atze and Mosaik, the first comic books appeared in the GDR. Mosaik became the figurehead of GDR comics .

During the 1980s there was a brief return of the generalists who wrote and sketched the stories. In the 1990s, the US and France reverted to the division. This development has led to the fact that the authors receive more attention and that the illustrators, especially in America, are selected by these authors. At the same time, underground comics began to develop in America in the 1960s around artists such as Robert Crumb and Gilbert Shelton , who devoted himself to the medium as a political forum. One of the most important representatives is Art Spiegelman , who created Mouse - The Story of a Survivor in the 1980s .

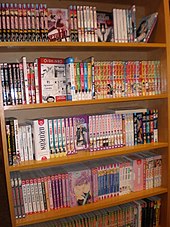

In Japan, the comic re-developed after World War II. The artist Osamu Tezuka , who among other things created Astro Boy , had a great influence on the further development of the manga in the post-war period. The comic found widespread circulation in Japan in all walks of life and from the 1960s and 1970s also reached many female readers. There were also more female draftsmen, including the group of 24 . From the 1980s, especially in the 90s, manga became popular outside of Japan, including well-known series such as Sailor Moon and Dragonball .

From the 1990s graphic novels gained in importance, such as autobiographical works such as Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis , Joe Sacco's reports on Palestine or the travel reports of Guy Delisle . Since Charley Parker's first webcomic , Argon Zark , appeared in 1995 , the Internet has also been used by numerous comic producers to publish and advertise their works, and serves comic readers and comic makers to exchange ideas.

Forms of comic

Comic strip

The comic strip (from the English comic strip , strip = strip) includes as a term both the daily strips ("day strips ") and the Sunday pages ("Sunday strips" or Sunday pages). The origin of comic strips can be found in the American Sunday newspapers, where they initially filled an entire page. The first comic strip is Hogan's Alley , later known as The Yellow Kid , by Richard Felton Outcault , which was created in 1894. From the turn of the century, comic strips were also distributed in newspapers in other English-speaking countries, in continental Europe not until the 1920s. They never found a distribution like in the USA.

In 1903 the first weekday daily strip appeared on the sports pages of the Chicago American , from 1912 onwards a continuous series was printed for the first time. The day trip, which was limited to black and white from the start, should also be economical in terms of space. Since it was only supposed to cover one bar, the length was limited to three or four images, which usually ended with a punch line. To this day it has been preserved that the comic strip has a fixed length that should go over one long side. Often certain motifs are varied and thus new perspectives are gained. Long-term changes are only made in absolutely exceptional cases, usually the introduction of new minor characters. In the Gasoline Alley series, the characters even age. If the stories appear daily, they are often used to determine a kind of story arc over the course of a week, which is followed by a new one in the next week.

That is why the practice increasingly prevailed that the Sunday pages had to function independently of the story arc, as there was a readership base exclusively for the Sunday newspapers who did not know the previous stories, and the Sunday strips were partly sold separately.

Due to the economic constraints involved in printing the strips, there were increasingly severe restrictions on the formal options during the Second World War. In addition, the newspaper strips lost their popularity and importance due to increasing competition from other media. Since the 1940s, the comic strip has not changed much in terms of form or content. Notable exceptions are Walt Kelly's Pogo , Peanuts by Charles M. Schulz and Bill Watterson's Calvin and Hobbes . The political comic strip Doonesbury , like Pogo , was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1975 . After expanding the content to include socially critical topics and formal experiments in the 1960s, the following artists moved within the existing conventions.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, newspaper strips have also been published collectively in book editions. By 1909, 70 such reprints had appeared. Even today, many current or historical comic strips are reprinted in other formats.

Booklet and book formats

In the 1930s, comic books were distributed in the United States in magazine form. In 1933, the Eastern Color Printing Company published a comic book in a form still in use today, which was folded from a printed sheet onto 16 pages and bound. The number of pages is usually 32, 48 or 64. Initially, the booklets were distributed by companies as promotional gifts for their customers, filled with collections of comic strips. Soon the booklets were sold directly as regular publications by publishers and filled with their own productions. The booklets Detective Comics (1937) and Action Comics (1938) from the Detective Comics publishing house were the first significant representatives, and the start of Action Comics was also associated with the first appearance of Superman . Because of their format, they were called comic books in the USA and have been the common form of distribution in many countries since the late 1940s.

After the Second World War, in some cases as early as the 1930s, the magazine format came to Europe and was distributed in the form of comic magazines such as Mickey Mouse magazine. The magazine combines various contributions from different authors and illustrators, which it adopts more often as sequels, and possibly supplements them with editorial contributions. A distinction must be made between magazines such as Yps aimed at young people , in which imported series such as Lucky Luke and Asterix and Obelix can be found alongside German articles and whose presentation has the character of a magazine, from collections aimed at adults such as Schwermetall or U-Comix . The most important Franco-Belgian comics magazines include Spirou (since 1938), Tintin (1946–1988) and Pilote (1959–1989).

Fix und Foxi by Rolf Kauka , one of the most successful comic series from German production, was published as a comic magazine from 1953. However, it no longer has any major economic relevance. In eastern Germany , their own comic magazines were called picture magazines or picture stories to distinguish them from western comics. The mosaic with its amusing, apolitical adventure storiesparticularly shaped thecomic landscape there. The mosaic of Hannes Hegen with Digedags was in 1955 in East Berlin founded. The comic magazine was latercontinuedwith the Abrafaxen . The mosaic still appears as a monthly issue with a circulation of around 100,000 copies in 2009, which no other magazine has with German comics. There are now hardly any successful magazines in Germany and comics are mainly published in book and album formats.

In Japan, Manga Shōnen was published in 1947, the first pure comic magazine, which was soon followed by others. In doing so, the company developed its own formats with up to 1000 pages, especially in comparison to the European magazine. At the height of sales in 1996, there were 265 magazines and nearly 1.6 billion copies a year. The most important magazine, Shōnen Jump , had a circulation of 6 million per week. The sales figures have been falling since the mid-1990s.

In addition to the comic books, the album and the paperback also prevailed. Comical albums appeared in France and Belgium from the 1930s. In them, the comics published in magazines are collected and printed as a complete story. Due to the use of 16-up printed sheets, their scope is usually 48 or 64 pages. In contrast to notebooks, they are bound like books, from which they stand out due to their format, usually A4 or larger. They are particularly common in Europe. Since there have been fewer comic magazines, comics in Europe are mostly published directly as albums without preprint. Well-known comics published in album form are Tintin and Yakari . In the 1950s and 1960s, Walter Lehning Verlag brought the Piccolo format from Italy to Germany. The 20 Pfennig booklets were sold successfully with the Hansrudi Waschers comics and shaped the German comic of the time.

Comic publications in book formats emerged in the 1960s and came to Germany with the publications of Eric Losfeld. The Funny Paperback Books , launched in 1967, are still published today. From the 1970s, the publishers Ehapa and Condor also established superheroes in paperback format, including Superman and Spider-Man . There were also humorous series in this format, such as Hägar . In Japan, as a counterpart to the European album, the book for the comprehensive publication of series established itself. The tankōbon formats that arose were also used in the West for the publication of manga in the 1990s. With Hugo Pratt in Europe and Will Eisner in the USA, stories were created as graphic novels for the first time from the 1970s , which were published in a similar way to novels , independent of fixed formats . The term "graphic novel" itself was initially only used by Eisner and only caught on much later. The increasing number of graphic novels are usually published in hard or soft cover book editions. Comics series that originally appeared in individual issues, such as From Hell or Watchmen , are collected in book form and referred to as graphic novels.

Comics creation

techniques

Most comics were and are created using graphic techniques , especially as drawings in pencil or ink . It is also customary to first draw preliminary drawings with pencil or other easily removable pens and then do a final drawing with Indian ink. As a supplement to this, the use of grid foils or prefabricated foils printed with image motifs is sometimes widespread. In addition to drawing with pen and ink, all other graphics and painting techniques as well as photography for the production of comics are possible and used, for example in photo novels . By the 19th century, when modern comics also established the techniques commonly used today, there was already a wide range of artistic processes for picture stories. For example, painting in oil and prints with engravings, frescoes, embroidery or windows made of colored glass. Comics were also created with relief and full plastic. Since the 1990s, production using electronic means such as the drawing board, which is often similar in appearance to traditional drawing, has become more widespread. In addition, with the exclusively electronic drawing, new styles and techniques emerged. 3D comics are a special form .

The decisive factor in the choice of technology was often that the images were reproduced using printing processes. Therefore works with graphics that consist of solid lines dominate. For colored images, surface colors or halftone colors from four-color printing are usually added to the printing process . With the spread of scanners and computers for reproduction and the internet as a means of dissemination, the possibilities for draftsmen to use and develop other means and techniques have increased significantly.

Artists and production processes

For a long time in America and Europe, the comic industry was almost exclusively composed of white, straight men. However, little was known about most artists in the first half of the 20th century. This enabled members of minorities to avoid prejudice. It was not until the 1970s that women and social minorities began to appear as authors and draftsmen. This often went hand in hand with the establishment of its own organizations, such as the Wimmen's Comicx Collective or the Afrocentric publishing house in the United States.

Up until the 19th century, comics and picture stories were almost exclusively made by individual artists. Through the publication of the comics in newspapers and previously in similar mass print media, the artists were more and more often working for a publishing house in the 19th century. Their product was still individual and series were discontinued if the artist did not continue them himself. At the beginning of the 20th century, there were more collaborations between draftsmen and authors who worked together on a series on behalf of a publisher. Increasingly series were also continued with other artists. In large publishers such as Marvel Comics or among the publishers of Disney Comics , style specifications have become established that are intended to enable a uniform appearance of series, even if the participants are changed. Nevertheless, there are artists in this environment who stand out and shape with their style. In contrast, comic studios developed that are more independent of publishers. Sometimes these are dominated by a single artist or simply exist to support the work of an artist. Such a constellation can be found, for example, at Hergé and is widespread in Japan. Based on the concept of auteur film coined by the directors of the Nouvelle Vague , the concept of auteur comic was also created , which, in contrast to conventional mainstream comics , which are based on the division of labor, is not a commissioned work, but rather as an expression of a personal artistic and literary signature that is continuously carried through the entire work of an author draws, arises. Depending on how they work - alone, in a team or directly for a publisher - the individual contributor has more or less leeway, which also affects the quality of the work.

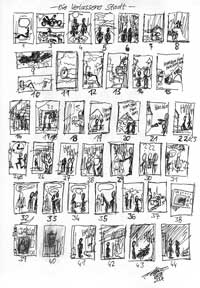

Both with publishers and studios of individual artists, the work is usually divided between several people. The writing of the scenario, the preparation of page layouts, the drawing of the pages, the indenting of pencil drawings and the setting of text can be carried out by different people. The production of parts of the picture such as drawing figures and background, setting hatching and grid foil and coloring can be distributed among several participants.

Distribution channels

Popular lithographs, early comics, and picture stories were sold in Germany by rag collectors who carried them with them. Later comics were distributed almost exclusively through newspapers in North America and Europe until the 1930s. With the comic books, a remittend system came up in the USA , in which the comics were sold via newspaper kiosks . Unsold copies were returned to the publisher or were destroyed at the publisher's expense. From the 1960s, pure comic shops were able to establish themselves and with them the “ Direct Market ”, in which the publisher sells books directly to the shop. Newly created formats such as the comic album or comic book were also brought to their customers in this way.

With the development of electronic commerce from the 1990s, direct sales from the publisher or directly from the artist to the reader increased, including the sale of digital instead of printed comics. This offers the advantage of lower production costs, which, together with the large reach for all sellers and marketing via social networks, leads to greater opportunities for smaller providers such as self-publishers and small publishers.

Legal Aspects

The handling of copyrights and rights of use to comics has been controversial throughout the history of the medium. The success of William Hogarth's picture stories led to them being copied by others. To protect the author, the English Parliament therefore passed the Engraver's Act in 1734 . Artists who create their works themselves and alone hold the rights to these works and can decide on their publication. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, new conflicts arose as more and more people were involved in a single comic, according to the editor or various artists and authors. This led, among other things, to the fact that the rights of a series were divided between a publisher and the artist or that the authors received little payment compared to the proceeds of the publisher. In the course of the 20th century, contracts were established between all parties involved, which led to a clear legal position.

Design language

In addition to a wide range of techniques, comics have developed their own formal language , as the medium is particularly dependent on pictorial symbols. These are used to clarify states of mind or to make non-objective elements of the events shown visible. Exaggerated but actually occurring “symptoms” such as drops of sweat or tears, or entirely metaphorical symbols are used. The speech bubble is particularly widespread as a symbolic representation of invisible language and at the same time a means of integrating text. For the symbolic representation of movement, especially “speed lines” are used, which trace the path of what is moved, or a schematic representation of several phases of movement. A wide range has developed in comics, especially when using various stroke, line and hatching forms as an expressionist means of conveying emotions. The font and size of text are used very much like the stroke. The use of colors, if any, is handled very differently. Since the mostly used two-dimensional colorations emphasize the contours and thus make the picture appear static and make it difficult for the reader to identify, the color composition is also of great importance for telling the story and the effect of the characters.

In addition to the actual symbols, the characters and the depicted scenery are often simplified, stylized or exaggerated. Different levels of the image, such as figures and backgrounds, but also different figures, can be abstracted to different degrees. There is a broad spectrum of content or formal abstraction , from photographic or photo-realistic representations to largely abstract forms or pure pictorial symbols. The stylized, cartoon-like representation of the characters involved is particularly important, as it enables the reader to easily identify with these characters. Different degrees of stylization can also influence the reader's identification and liking in this way. According to Scott McCloud, it is common in many styles, such as the Ligne claire or Manga , to combine strongly stylized figures and a more realistic background in order to allow the reader to "safely enter a world of sensual stimuli" behind the mask of a figure. He calls this the "masking effect". This can also be used flexibly, so that changing the type of representation of a figure or an object also leads to a different perception of it. The stylization and exaggeration of features of the figures also serves to characterize and distinguish them for the reader. The use of physical stereotypes arouses or deliberately breaks the reader's expectations.

Graphic storytelling

The way in which the content of the story is divided into images, which excerpts and perspectives the author chooses and how the panels are arranged is central to storytelling with comics . Eckart Sackmann calls the three principles of narration in comics the continuous, integrating and separating, referring to the art historian Franz Wickhoff . In the first, the events are lined up without separation ( e.g. Trajan's Column ), the integrating principle combines the temporally staggered scenes in one large picture ( e.g. picture arches or Viennese Genesis ). The separating principle that prevails in modern comics divides the processes into successive images. From the differences in content between successive panels, the reader draws conclusions about the events by induction , even without showing every moment. Depending on the proximity or distance of the images, the reader is given different degrees of scope for interpretation. Scott McCloud arranges the panel transitions into six categories: From moment to moment, from action to action (with the object viewed remaining the same), from object to object, from scene to scene, from aspect to aspect and finally the change of image without any logical reference. He notes that categories 2 to 4 are particularly often used for narratives, while the last category is completely unsuitable for narration. The extent to which certain categories are used varies widely depending on the narrative style. There is a significant difference between Western comics up to the 1990s and manga, in which categories 1 and 5 are used significantly more. Dietrich Grünewald , on the other hand, defines only two types of arrangements: the “close” and the “wide sequence”. While the first depicts actions and processes and has primarily shaped comics since the end of the 19th century, the second is limited to clearly more distant, selected stations of an event. To combine these with one another requires a more attentive consideration of the individual picture; Until the modern comic, this was the predominant narrative style. The panel transitions influence both the perception of movement and which aspects of the action or the represented are particularly perceived by the reader, as well as the time felt by the reader and the flow of reading.

The layout of the pages is also important for the perception of time and movement. Movement, and with it time, is also represented by symbols. The use of text, especially the language spoken by characters, also affects the impression of time told . The use of various panel forms and functions also serves to narrate. The use of “ establishing shots ” or a “ splash panel ”, which introduce a scene or a new place of action, is widespread. These are also an application of partially or completely borderless panels. The selection of the image section and the displayed moment of movement influences the flow of reading insofar as the choice of the “fertile moment”, i.e. the suitable pose, supports the illusion of movement and thus induction.

The integration of text in the comic takes place via speech bubbles as well as the placement of words, especially onomatopoeia and inflectives , directly in the picture or below the picture. Text and image can work together in different ways: complement or reinforce each other in terms of content, both convey the same content or be without direct reference. Likewise, a picture can be a mere illustration of the text or it can only be a supplement to the picture.

On the one hand, the reader of the comic perceives the overall picture of a page, a comic strip or an individually presented panel as a unit. This is followed by consideration of the individual panels, the partial content of the images and the texts, usually guided by the page layout and image structure. Both consecutive as well as simultaneous, abstract and vivid perception take place. The often symbolic representations are interpreted by the reader and placed in a context that is known to him, and the events presented and their meaning are actively constructed from them. On the basis of Erwin Panowsky's work, Dietrich Grünewald names four content- related levels of visual history. The first level, “pre-iconographic”, is that of the represented forms, Grünewald also calls this the “staging”, ie the selection and arrangement of the forms as well as the images and panels on the page. The second, " iconographic " level includes the meaning of the forms as symbols, allegories, etc. A. The “ iconological ” third level is that of the actual meaning and content of the work, as it emerges from the context of their time and the artistic work of the Creator. He sees a fourth level in the picture history as a mirror of the time in which it was created and in what it says about its artist, its genre or its social context.

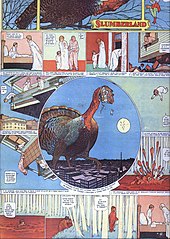

Content aspects

The comic as an art form and medium is not tied to any genre. Nevertheless, certain genres are particularly widespread within comics or have their origin in it. Series such as Krazy Kat created a genre of its own in the form of the “ Funny Animal ” comic strip at the beginning of the 20th century , which was later also used in animated films. The humorous comics that have emerged since then are commonly referred to as Funnys . In addition, stories from the everyday life of the readers or about realistic or fantastic journeys were primarily distributed. The American adventure comics of the 1930s, together with the film of the time, shaped crime and pirate stories, westerns and science fiction . At the same time, the semifunny was created as an intermediate form of funny and adventure comic . With the superhero , a comic genre of its own emerged in the USA at the end of the 1930s, which later found itself in film and television in particular. The briefly extensive emergence of comics with horror - and particularly violence-oriented crime thriller topics, mainly published by the publisher EC Comics , was ended by the Comics Code at the beginning of the 1950s.

In addition to humorous newspaper strips, a tradition of somewhat longer adventure stories has developed in European comics, of which Hergé and Jijé are the most important early representatives . In Japan, with the development of the modern manga, a large number of genres emerged that are peculiar to the medium and later also established themselves in anime . Some important genres, such as Shōnen and Shōjo , categorize not according to the subject of the work, but according to target group, in this case boys and girls. A female readership was also addressed, to an extent not previously achieved by the comic medium.

After comics with romantic stories, which were traditionally aimed at girls, had almost completely disappeared in Western comics, female cartoonists and comics for a female audience could only slowly gain acceptance from the 1970s. At the same time, underground comics with artists such as Robert Crumb and Art Spiegelman became an expression of the counterculture in the USA. As in Japan, more and more works with political and historical topics, later also biographical works and reports, were published and the graphic novel or Gekiga developed as a collective term for such comics.

Up until the 19th century, comics primarily took up the everyday life of their audience in a funny or satirical way, conveying historical events or religious topics. With modern comics, works with an entertainment function or political intention were also accompanied by knowledge-imparting non-fiction comics and comic journalism .

Another important genre of comics is the erotic comic. The whole range of erotic representations is represented; from romantic, transfigured stories to sensually stimulating works to pornographic content with depictions of various sexual practices. Important representatives of the genre are Eric Stanton , Milo Manara and Erich von Götha , but also the German draftsman Toni Greis .

Relationship and differences to other media

Movie

The reader of a comic combines the contents of the individual panels into one event. So that this works as well as possible, techniques are used that are similar to those found in film art . The individual panels show setting sizes such as long or half-close , it is switched between different perspectives. Almost all the techniques of film art have their counterparts in comics, whereby in the comic the variable panel frame makes it even easier to change the section than in the film . In many comics , the Establishing Shot is equivalent to an “opening panel” or a splash panel that shows the scenery.

The close relationship is also evident in the creation of storyboards during the production phase of a film, which outline the course of the film and, in particular, the camera position in a comic, and serve as inspiration or template for the director and cameraman . The textual draft of a comic, written by the author , is called a " script " and serves as the basis for the draftsman's work. While the “information gaps” given by the Gutter structure in the ( sketchy ) film storyboard can be neglected and closed in the later product through cinematic means, they require greater attention from comic book authors so that the final product can be read by the readership fluently is guaranteed.

In contrast to the film, however, the comic requires filling in the gaps between the panels. After all, unlike in the film where both a change of perspective by panning and / or zoom as well as movements of people and objects within a setting can be taught, it can in the comic within a panel, possibly by moving lines , the other in movement pattern superimposed images or panel are indicated in the panel . There is inevitably an information gap between the panels that is generally larger than that between the setting and the setting. The comic book reader is therefore more challenged than the film viewer through independent thinking - “ induction ”; see. Induction (film) - to construct a dynamic process from static images. In this way, and also because of the generally lower number of people involved in a work, the relationship between author and consumer is more intimate and active in comics than in film. Another difference is the reading or viewing speed and the order in which the images are captured. In the film this is given, the comic reader, on the other hand, freely determines this, but can be guided by the artist. The same applies to the content of the individual images, the perception of which in a film is guided by the depth of field and restricted to a simultaneous action. In comics, on the other hand, all parts of the picture are usually shown in focus and there is the option of showing two parallel actions, for example comments from characters in the background, in one picture.

The strongest relationship between the media film and comic is shown in the photo comic , since the individual images on the comic page are not drawn, but produced with a camera, as in a film.

literature

Similar to the presentation of the plot in purely word-based literary forms , the active participation of the reader is required in comics. In contrast to pure text literature, the mental cinema is usually more visually pronounced when reading comics, the use of pictorial means is the most significant difference between comics and text literature. By using pictorial symbols, the comic appears more directly to the reader than the narrative voice of prose. The author can also show a personal style not only through the choice of words, but also in the pictures. Scott McCloud cites the need to create text cohesion through graphic means as an important criterion for comics. Because of this criterion, comics are a form of literature from a literary perspective , although without prejudice to this they represent an art form in their own right from an art historical perspective .

theatre

In the meaning of striking poses, symbols and stylized figures, comics have similarities with theater, especially with paper theater . In both media, the recipient should recognize the characters through highlighted features, in the face or the costume, in order to be able to follow the action. Known patterns and prejudices are addressed through stereotypes, which make it easier to understand the story or serve narrative tricks. The representation of the place of action through a simple but concise background or a stage design is important in both media. Some of the theater's techniques to convey spatial depth and three-dimensionality, such as the superimposition of characters from paper theater, the escape perspectives of Renaissance theater or the rise of the stage floor towards the rear, were adapted from comics. While in the theater, however, and to a limited extent also in the paper theater, movement can be represented directly, the comic is dependent on the use of symbols and the illustration of several phases of movement. It is similar with sounds and language. In comics, on the other hand, it is easier to depict parallel actions and jumps in time and place.

Visual arts

Since the comic uses the means of the visual arts to depict the plot, there are some overlaps between the two art forms. In both of these, the choice of image detail, perspective and the depicted moment or pose is important. The correctly chosen “fertile moment” makes a picture look more lively and convincing and supports the flow of reading in comics. Methods of representing movement that Futurist artists explored later found use in comics.

public perception

In the early days of modern comics, the medium was seen as entertainment for the whole family. Serious artists like Lyonel Feininger also dealt with the comic and Pablo Picasso was enthusiastic about the Krazy Kat strip . Only with the restriction of the strips to simple gags and the establishment of television as the predominant family entertainment medium, the perception of comics in the USA changed.

Increasingly, comics were accused of exerting a brutal influence on young readers that led to a superficial, clichéd perception of their environment. An article by Sterling North , in which attention was first drawn to the alleged danger of comics, initiated a nationwide campaign against comics in 1940 in the United States. The climax were efforts in America in the 1950s to ban horror and crime comics such as Tales from the Crypt by the publisher EC Comics . In 1954 the psychiatrist Fredric Wertham published his influential book Seduction of the Innocent , in which he sought to demonstrate the harmful effects of crime and horror comics on children and young people. According to a study from 2012, many of the research results in Wertham's book were deliberately manipulated or even invented by the author; In its time, however, it was widely received and had a lasting effect on the production and understanding of comics. Senate hearings followed on the problem of comics, which did not lead to a general ban on comics, but to the introduction of the Comics Code , a self-censorship of the comic industry. The obligations laid down here, such as the prohibition on making criminals appear sympathetic in any way and their actions understandable, led to a narrative flattening of the comics. For a long time, the perception of comics in the English-speaking world was limited to genres such as the superhero comic or funny animal. In Germany in the 1950s there was a similar, so-called “dirt-and-trash” campaign. In this comics were categorized as the cause of ignorance and dumbing down of young people, as "poison", "addictive opium" and "popular epidemic". At the height of the campaign, comics were burned and buried with publicity. The demands of the critics were similar to those in the United States, including a general ban on comics. However, this was not fulfilled, the Federal Court of Justice demanded a specific examination of the individual representation. The newly established Federal Testing Office for writings harmful to young people ultimately indexed significantly fewer works than the critics had requested. As in the USA, a voluntary self-regulation (FSS) was founded in Germany, which checked comics for moral violations and violence and provided them with a seal of approval. There were similar initiatives and developments in other European countries. As a result, comics, especially in Germany, have been the epitome of junk literature since the early 1950s . According to Bernd Dolle-Weinkauff's opinion in 1990, the long-term consequence was not the suppression of comics, but the deterrence of authors, draftsmen and publishers with high quality standards, so that “the production of trash [...] was strongly encouraged”.

The perception of comics was shared in the aftermath of the “dirt and trash” campaign - series of images from Dürer to Masereel were recognized as high culture , as were some works of early modern comics, including Wilhelm Busch . The works of the 20th century, which were disseminated as mass media, were seen as entertaining, inferior art. This has weakened since the 1970s, as on the one hand popular culture is generally being devalued less and less and influenced recognized high art, on the other hand works such as Art Spiegelman's Mouse - The Story of a Survivor have changed the public perception of comics. Since then, for example, comics have also been reviewed in feature pages . In the 4/1987 edition of the Swiss Youth Writings Works, the headline was an article From Trash to School Aids by Claudia Scherrer. With the words "The medium of comics has become so socially acceptable that even the Swiss youth publication SJW has included picture stories in its program - although" [sic] "the SJW was founded to protect young people against junk literature" it also recommended works by other publishers . Comics have also been relevant to teaching in Germany and Austria since the 1970s, both as a subject in German, art or social studies classes and as a teaching aid in other subjects.

Criticism of the content of comics since the 1960s often refers to repetitive, only slightly varied motifs, as are particularly common in the adventure genres (western, science fiction, fantasy). The reader is offered a simple world in which he can identify with the good and achieve a (partial) victory with it. It is countered that the attraction for the reader lies precisely in the fact that he can break out of his complex but unexperienced everyday world in stories with such motifs. The older fairy tales offer a comparable approach and appeal to the adventure genres. Repetitive topics and structures would provide an easy introduction to conversational reading. After all, the reader prefers stories that do not deviate too far from his expectations, which forces artists and publishers who want to reach a broad readership to a certain degree of conformity. However, this has a similar effect on other popular culture media, such as film and television. Nevertheless, the motives evolve and participate in social changes. This can be seen, for example, in the development of superhero comics, which over time have also included topics such as equality and social commitment. In terms of content, there was also criticism of comics, especially Disney stories in the 1970s , in which the conveyance of imperialist, capitalist or other ideology was suspected. However, there were also contradicting interpretations, so the figure of Dagobert Duck can be read as a belittling of capitalism, but also as satire with the means of exaggeration. Both with the reader's escape from everyday life into a fantasy world, in which negative effects on the life and perception of the reader are assumed, as well as the fear of ideology, the view of the respective comic works depends primarily on which ability to Distancing and interpretation are trusted to the reader. In addition, there are many comics that often do not achieve a great deal of awareness, but in terms of content move beyond the criticized motifs and clichés.

In the USA in particular, there were repeated disputes and lawsuits over comics that were pornographic or viewed as such, since comics were perceived as purely children's literature. In Germany, legal measures such as the confiscation of comics remained the exception; courts generally gave artistic freedom a higher priority than protection of minors, even in comics. In lexical works, comics were mostly judged disparagingly. The Brockhaus Encyclopedia, in its 19th edition, Vol. 4 (1987), found that most of the series can be characterized as trivial mass drawing, as “entertainment aimed at consumption, determined by repetitions, by clichés and short-term distraction for its readers of their everyday problems ”. But there is also a comic offering that is committed to artistic quality.

Comic research

Scientific writings on comics appeared from the 1940s onwards, but were often one-sided and undifferentiated critical of the medium and did not deal with the functions and aspects of comics. In the USA, Martin Sheridan's Comics and Their Creators appeared in 1942, the first book devoted to comics. This was followed by occupations with the history of comics and the first writings that were supposed to systematically develop the scope of published works. At first, comics received little scientific attention in Germany because of the “filth and trash” campaign of the 1950s. In certain circles of literary studies, the comic was accused of language impoverishment, which should be proven by the more frequent use of incomplete sentences and slang expressions in comics compared to youth literature. It was misunderstood that the text in most comics consists almost exclusively of dialogues and has a function that is more comparable to cinema and theater than literature. The criticism of language impoverishment can also be described as outdated and ahistorical for the reason that the use of colloquial and vulgar language in literature has long ceased to be a quality criterion.

A more serious, cultural-scientific occupation began in France in the 1960s, beginning with the establishment of the Center d'Études des Littératures d'Expression Graphique (CELEG) in 1962. The volume of publications increased, in addition to history, genres, genres, examines individual works and artists. Lexical works on comics appeared, first exhibitions took place and museums were founded. Soon this also happened in other European countries, North America and Japan. Over time, the first courses in comics came into being. The more extensive academic study of comics began in the United States in the 1970s and was initially limited to sociological aspects. Under the influence of the 1968 movement , the comic was initially viewed from the perspective of the mass medium or mass drawing goods and defined as such. Sociological and media-critical considerations were therefore initially predominant, later also psychological considerations were added, such as the investigation of the effects of depictions of violence on children. Even after this more restricted definition was rejected in favor of the current one by the 1990s at the latest, the consideration of these aspects remains an important part of comic research and theory. Investigations into storytelling with comics initially took place using methods that were developed for text literature and adapted for comics. In Berlin, the Comic Strip Interest Group (INCOS) was the first German association to promote comic research. In 1981 he was followed by the association for comics , cartoon, illustration and animation (ICOM), which organized events in its early years, including 1984 with the Erlangen comic salon, the most important German event on comics and supports comic research. The COMIC! Yearbook, which has been appearing since 2000 as the successor to the association's own specialist magazine, contains interviews and articles on the structure and development of the medium. In 2007 the Society for Comic Research was founded. Since the 1970s, specialist magazines and fanzines on comics have also been published in German-speaking countries , including Comixene , Comic Forum and RRAAH! . Since then, museums have also shown exhibitions on comics and the systematic recording of German works began. In the GDR, on the other hand, there was only little scientific study of comics, which was also focused on the distinction between “capitalist comics” and “socialist visual history”, i.e. the productions of the socialist countries.

Together with the first research into comics, the discussion began in the 1970s as to whether comics were an art form in their own right. In the 1990s, comics were increasingly recognized as art and the forms and semiotics of comics were examined, for which narrative theories of comics were also developed. Empirical studies of reading behavior have also taken place since then, but often motivated by the publishers and with methods that are questioned. The Laboratory for Graphic Literature (ArGL), founded in 1992 at the University of Hamburg , established itself in university research, and symposia and conferences are held sporadically.

See also

literature

- Bernd Dolle-Weinkauff: Comics. History of a popular form of literature in Germany since 1945. Beltz-Verlag, Weinheim 1990, ISBN 3-407-56521-6 .

- Will Eisner : Comics & Sequential Art. Principles & Practice of the World's Most Popular Art Form! Poorhouse Press, Tamarac FL 1985, ISBN 0-9614728-1-2 .

- Wolfgang J. Fuchs, Reinhold C. Reitberger : Comics. Anatomy of a mass medium. (39th – 43rd thousand). Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1977, ISBN 3-499-11594-8 .

- Dietrich Grünewald: Comics . Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 2000, ISBN 3-484-37108-0 .

- Harald Havas , Gerhard Habarta (ed.): Comic worlds. History and structure of the ninth art. Edition Comic Forum 1992, ISBN 3-900390-61-4 .

- Burkhard Ihme (Ed.): COMIC! Yearbook. Interest association Comic eV ICOM, Stuttgart (published annually since 2000), ISSN 0945-926X

- Alex Jakubowski (author), Sandra Mann (photos): The art of collecting comics , edition Lammerhuber, Baden, June 2015, ISBN 978-3-901753-80-0 . - 15 comic collectors from Germany, Mallorca, Austria give an insight into their treasures.

- Andreas C. Knigge : Everything about comics. Europa Verlag, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-203-79115-3 .

- Andreas C. Knigge: Comics. From mass paper to multimedia adventure. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1996, ISBN 3-499-16519-8 .

- Scott McCloud: Read Comics Right . (The invisible art). 5th edition, modified new edition. Carlsen, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-551-74817-9 .

- Eckart Sackmann (Ed.): German comic research. comicplus +, Hildesheim and Leipzig 2004–2014 (published annually), ZDB -ID 2297283-3

- Achim Schnurrer , Riccardo Rinaldi : The Art of Comics. Edition Aleph, Heroldsbach 1985, ISBN 3-923102-05-4 .

Web links

- Link catalog on the subject of comics and caricatures at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- Lambiek Comiclopedia , database of comic artists and authors (English)

- Grand Comic Book Database (GCD) , comic book database (English)

- German comic guide

- ICOM - The Association of Comics eV , association of artists, publishers and readers

- Audio interview with Dietrich Grünewald, Chairman of the Society for Comic Research

Individual evidence

- ↑ Scott McCloud: Read Comics Correctly. Carlsen, 1994. pp. 12-17.

- ^ Will Eisner: Comics and Sequential Art . WWNorton, New York 2008. pp. Xi f.

- ↑ a b c d e f Eckart Sackmann : Comic. Annotated definition in German Comic Research , 2010. Hildesheim 2009. pp. 6–9.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Grünewald, 2000, pp. 3-15.

- ^ Andreas Platthaus : United in comics - A story of picture history . Insel taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig, 2000. pp. 12–14.

- ↑ a b c Scott McCloud: Reading comics correctly . Cape. 4th

- ^ Alfred Pleuß: Picture stories and comics. Basic information and references for parents, educators, librarians , p. 1. Bad Honnef 1983.

- ↑ Brockhaus Vol. 2, 1978, p. 597.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Grünewald, 2000, chap. 3.

- ↑ Frederik L. Schodt: Dreamland Japan - Writings on Modern Manga . Stone Bridge Press, 1996/2011, p. 34.

- ↑ a b Pleuß 1983, p. 3.

- ↑ a b c d e f Scott McCloud: Reading comics correctly . Pp. 18-27.

- ↑ Andreas Platthaus: United in the comic . Pp. 15-17.

- ↑ Stephan Köhn: Japan's Visual Turn in the Edo period . In: German Film Institute - DIF / German Film Museum & Museum of Applied Arts (Ed.): Ga-netchû! The Manga Anime Syndrome . Henschel Verlag, 2008. p. 43.

- ↑ F. Schiller, Avanturen des neue Telemach online at Goethezeitportal.de.

- ↑ a b Andreas Platthaus: United in the comic . P. 25 f.

- ↑ Bernd Dolle-Weinkauf: Comic . In: Harald Fricke (Hrsg.), Klaus Frubmüller (Hrsg.), Klaus Weimar (Hrsg.): Reallexikon der deutschen Literaturwissenschaft . Walter de Gruyter, 1997, p. 313 ( excerpt (Google) )

- ↑ Roger Sabin: Ally Sloper: The First Comics Superstar? ( Memento from May 28, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (Link from archive version) In: Image & Narrative . No. 7, 2003.

- ↑ Andreas Platthaus: United in the comic . P. 27 ff.

- ↑ Frederik L. Schodt and Osamu Tezuka (preface): Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics . Kodansha America, 1983. p. 42.

- ↑ Andreas Platthaus: United in the comic . Pp. 65-74, 155-166.

- ↑ Andreas Platthaus: United in the comic . Pp. 137 f., 167-193, 172-176.

- ^ Paul Gravett: Manga - Sixty Years of Japanese Comics . Egmont Manga & Anime, 2006. pp. 154-156.

- ^ Andreas C. Knigge: Foreword. In: Paul Gravett (ed.) And Andreas C. Knigge (transl.): 1001 comics that you should read before life is over . Zurich 2012, Edition Olms. P. 7.

- ↑ Knigge: Comics , 1996, pp. 15 ff., 176 ff.

- ↑ Knigge: Comics , 1996, p. 92 ff.

- ↑ a b Knigge: Comics , 1996, p. 110 ff.

- ↑ a b Knigge: Comics , 1996, p. 330 f.

- ↑ Advertising and Selling , No. 39, September 24, 2009, p. 85.

- ↑ Knigge: Comics , 1996, 242.

- ^ Frederik L. Schodt: Dreamland Japan. Writings On Modern Manga . Stone Bridge Press, Berkeley 2002. pp. 81 ff.

- ↑ Knigge: Comics , 1996, p. 221 f.

- ↑ Scott McCloud: Read Comics Correctly. P. 30.

- ^ A b McCloud: Making Comics , pp. 184-207.

- ↑ a b Scott McCloud: Reinventing Comics , chap. 4th

- ↑ a b c d Grünewald, 2000, chapter 5.

- ^ Carl Rosenkranz: On the history of German literature . Königsberg 1836. p. 248 f. Quoted from Grünewald, 2000, Chapter 5.

- ↑ Scott McCloud: Reinventing Comics , chap. 2.

- ↑ Scott McCloud: Reinventing Comics , chap. 6th

- ↑ a b Scott McCloud: Reading Comics Correctly , chap. 5.

- ↑ Scott McCloud: Reading Comics Correctly , chap. 8th.

- ↑ Scott McCloud: Reading Comics Correctly , chap. 2.

- ↑ Scott McCloud: Making Comics , chap. 2.

- ↑ a b Scott McCloud: Reading Comics Correctly , chap. 3.

- ↑ a b Scott McCloud: Making Comics , chap. 4th

- ↑ Scott McCloud: Reading Comics Correctly , chap. 6th

- ↑ Knigge: Comics, 1996. pp. 112-144.

- ↑ Knigge: Comics, 1996. pp. 179-187.

- ↑ Tom Pilcher : Erotic Comics. The best of two centuries. With 400 colored illustrations . Knesebeck Verlag, Munich 2010.

- ↑ a b Scott McCloud: Reinventing Comics , chap. 1.

- ↑ Burkhard Ihme: Montage in the comic . In Comic Info 1 + 2/1993.

- ↑ Carol L. Tilley: Seducing the Innocent: “Fredric Wertham and the Falsifications that Helped Condemn Comics”, in: Information & Culture: A Journal of History , Vol. 47, No. 2. Cf. also: Dave Iitzkoff: “Scholar Finds Flaws in Work by Archenemy of Comics ” , in: New York Times , February 19, 2013.

- ↑ a b c d Scott McCloud: Reinventing Comics ; Cape. 3.

- ↑ after Grünewald, 2000, chap. 7.1; therein reference to Wolfgang J. Fuchs / Reinhold Reitberger: Comics-Handbuch . Reinbek, 1978, pp. 142ff., 157, 186ff .; Bernd Dolle-Weinkauff: The science of dirt and trash. Youth literature research and comics in the Federal Republic . In: Martin Compart / Andreas C. Knigge (Hrsg.): Comic-Jahrbuch 1986 . Frankfurt / M. 1985. pp. 96 ff., 115 .; Andreas C. Knigge: To be continued. Comic culture in Germany. Frankfurt / M. 1986. pp. 173ff .; Broder-Heinrich Christiansen: Young people endangered by comics? The work of the Federal Inspectorate for Writings Harmful to Young People in the 1950s . Master's thesis Göttingen 1980.

- ↑ Grünewald, 2000, chap. 7.2.

- ↑ Andreas C. Knigge : Recommended Comics. In: Andreas C. Knigge (Ed.): Comic Jahrbuch 1987 , Ullstein, Frankfurt / M., Berlin 1987, p. 186 ISBN 3-548-36534-5 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Grunewald, 2000, chap. 6th

- ↑ Grünewald, 2000, chap. 7.3. In it reference to Alfred Clemens Baumgärtner: The world of adventure comics . Bochum, 1971. pp. 21f .; Bruno Bettelheim: Children need fairy tales . Munich, 1980. pp. 14f .; Michael Hoffmann: What children “learn” from Mickey Mouse comics. In Westermanns Pedagogical Contributions 10/1970 .; David Kunzle: Carl Barks. Dagobert and Donald Duck. Frankfurt / M., 1990. p. 14 .; Gert Ueding: Kitsch rhetoric . In Jochen Schulte-Sasse (Hrsg.): Literarischer Kitsch . Tübingen, 1979. p. 66 .; Thomas Hausmanninger : Superman. A comic series and its ethos . Frankfurt am Main 1989 .; Dagmar v. Doetichem, Klaus Hartung : On the subject of violence in the superhero comics . Berlin 1974, p. 94 ff.

- ↑ after Grünewald, 2000, chap. 7.1; therein reference to Rraah! 35/96, p. 24f .; Achim Schnurrer and a .: Comic: Censored . Vol. 1. Sonneberg, 1996; Lexicon of Comics . 21. Erg. Lief. 1997. p. 20.

- ↑ Brockhaus Encyclopedia : in 24 vol., 19th completely revised edition, vol. 4 Bro-Cos, Mannheim 1987, Brockhaus.

- ↑ Achim Schnurrer (Ed.), Comic Zensiert , Volume 1, Verlag Edition Kunst der Comics , Sonneberg 1996, p. 23.