Lady's mantle

| Lady's mantle | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

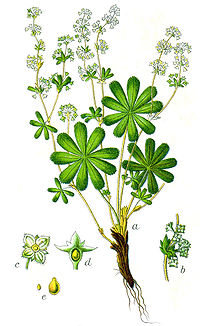

Common lady's mantle ( Alchemilla vulgaris ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Alchemilla | ||||||||||||

| L. |

Lady's mantle ( Alchemilla ) is a plant genus within the family of the rose family (Rosaceae). The species are widespread in the Old World in Europe , Asia and Africa and thrive primarily in the mountains. Very hairy forms are also known as silver mantles. They are herbaceous to shrub-shaped plants, their flowers are small, inconspicuous and have no petals . Reproduction takes place predominantly, almost exclusively in the European species, agamosperm (via asexual seed formation). Of the approximately 1000 species, around 300 are native to Europe. In Europe the species were used as folk medicinal plants. Some species make good fodder, very few are cultivated as ornamental plants.

description

Appearance and indument

The lady's mantle species are deciduous dwarf or subshrubs or perennial herbaceous plants . The shoot axes are above ground, sometimes partially lignified. Their branching is monopodial . The main axis is lying, forms adventitious roots and is covered with petiole and minor leaf remnants. At the top of the main axis there is a base sheet rosette. The vegetative parts of the plant above ground are often hairy. The hairs ( trichomes ) are always unbranched and mostly straight; Glandular hairs are very rare ( indument ).

root

The main roots are replaced by adventitious roots relatively soon after germination . The strength of the rooting depends on the degree of moisture in the subsoil, but it also varies depending on the section . In the Alpinae section , which consists of crevice inhabitants , the shoot axis only forms roots at greater intervals, while the Erectae and Ultravulgares sections have strong roots. In the Pentaphylleae section , the roots are tightly tufted.

Stem axis

In the upright, tropical shrubs, the axes (with the exception of the inflorescence) are usually all the same. The thickening of the marrow cylinder in the lying basic axis, which occurs in the European species, but also in many tropical species, as well as the differentiation into long and short shoots is a derived feature. The upright (orthotropic) growth is considered to be the original growth form, the seedlings also of the creeping species usually grow upright in the first year. Adult plants also form individual, short, upright side shoots. These are poorly nourished due to the low rooting and die off when dry .

leaves

The leaves are divided into a petiole and a leaf blade. The leaf blades are lobed to fingered and toothed on the edge. In the bud , the leaves are folded several times, each leaf lobe individually, creating a fan. The pleated fan can often be recognized by unfolded leaves. The stipules can be fused with the petiole and on the opposite side of the stem axis, this is always the case with the Central European species. The stipules thus form a tute . The fusion of the stipules with one another is never complete, the open part between the lobes is called the incision. As a third form of intergrowth, the two stipules can be intergrown above the petiole, this is referred to as auricle are intergrown or free .

The following leaf features are considered to be original within the genus: a short, runny leaf stalk with collateral vascular bundles , a small number of leaf lobes and leaf teeth, a shallow depth of division and short teeth.

In lady 's mantle, the stipules act as bud scales : They protect the vegetation cone and young axes. There are two taxonomically relevant bud types: in the first type, the young leaf blade is surrounded by its own tute; in the second type, the resulting leaf is only surrounded by the tute of the next older leaf, its leaf blade is always outside its own tute. In addition to the adhesions described above, there is another variant of protection: the stipules dry up quickly in some sections and form a multi-layered, perennial insulating layer (tunic) around the young axes.

The leaves have water fissures ( passive hydathodes ) at the end of the leaf lobes . Liquid water is separated from these during the night ( guttation ).

inflorescence

The inflorescence axes are formed laterally. Arm- flowered pleiochasia are considered to be the original form of the inflorescence . From these lines of development led on the one hand to larger inflorescences, on the other hand to impoverished inflorescences, sometimes only one or two flowered. The whole inflorescence is a closed thyrse , which, however, can have different effects depending on the arrangement: panicle-like , grape- , double- grape -like etc. It is composed of different numbers of members (two to ten), depending on the section. In the tropical shrubs, the lower partial inflorescences are more pronounced ( basiton ), as in the Alpinae and Pentaphylleae sections . Inflorescences in the Erectae section are broad, relatively short and spiral-shaped , while those in the Ultravulgares section are rather racemose and narrow.

blossoms

The flowers are small and green or yellowish in color. Comparatively large flowers are considered original. Within a plant, the larger flowers are on the lower, arm-flowered inflorescences, the smaller ones on the rich-flowered stems. The upper limit for the flower diameter is usually five to six millimeters, with section erectae at seven millimeters. The flowers are four-fold, five-fold terminal flowers occur regularly in the Ultravulgares and Pentaphylleae sections . Three or two-fold flowers can also appear on the terminal branches of inflorescences.

The flower cup is an intergrowth of the sepals and is often referred to as a sepal cup. It is cylindrical, bell-shaped or jug-shaped. The sepals that remain free are usually referred to as "sepals" in the literature. Thereby, a slight adhesion of the sepals is always accompanied by long free sepals. This is considered an original feature. The (seldom missing) outer calyx is not interpreted as a stipule formation in lady's mantle, but as a protuberance of the sepals. Petals are missing. A discus follows inward, secreting nectar from several columns of juice , which emerges in elongated portions.

The four stamens stand within the disc on a gap (alternating) to the sepals. They are interpreted as transformed petals , which is supported by various atavistic forms. The original stamen circles have therefore disappeared. The pollen is tricolporate (three germinal furrows / pores), the outline is triangular in polar view.

A few clans of the genus have several free carpels (up to ten). There are two carpels in several African sections. The Eurasian species have only one carpel, rarely have individual flowers two. The stylus stands upright, the stigma can be hooked or spoon-shaped on one side.

fruit

The fruits are solitary nuts (the term achenes would be more correct for flowers with only one carpel , but is practically not used for lady's mantle). Several species have a beak. The nut is completely or partially enclosed by the thin and dry flower cup when ripe.

Chromosomes and ingredients

The chromosomes in Alchemilla are very small and numerous, which makes many figures uncertain. The lowest confirmed chromosome number in Central Europe is 2n = 96. Alchemilla fissa has the highest number in Central Europe with 2n = 152. Alchemilla faeroensis has 2n = 182–224. For the African Alchemilla johnstonii (section Geraniifoliae ) 2n = 32 was determined. The basic chromosome number is often given as x = 8. All European species today are highly polyploid .

The plants are rich in tannins . In addition, other bitter substances and essential oils were detected. The seeds are rich in fatty oils . Calcium oxalate drusen are found in all parts of the plant .

ecology

Alchemilla species grow as Chamaephytes or Hemicryptophytes .

Flower ecology

The flowers are proterandric (formerly male). They are open day and night. A display device is not developed, only in the erectae section with dense, yellow inflorescence one is present. Insects are attracted by the cheese- or horse-apple- like smell of the flowers. The visitors are similar to those of umbellifers (Apiaceae), but much less numerous. Bugs , lacewings , diptera , hymenoptera and beetles have been observed as flower visitors in the low-lying areas, while in the mountains it is predominantly flies visiting manure .

Reproduction

The vast majority of the species, almost all of them in Central Europe, reproduce asexually by forming their seeds without fertilization, i.e. agamosperm . Due to the high number of ploidies, their meiosis does not proceed normally.

When pollen is formed, there are meiosis disorders: the tetrad divisions are not carried out, or the pollen grains are abnormally shaped, empty or at least not capable of germination. In some species, such as Alchemilla lapeyrousii , the anthers already wither . The anthers usually do not open well and the pollen forms a lumpy mass.

The embryo sac arises without meiosis ( apospor ) from the diploid (= sporophytic ) cells of the nucellus . The egg cell is therefore also diploid and develops into an embryo without fertilization (diploid parthenogenesis ). The embryo can also arise from other cells of the embryo sac or the nucellus. In some species there is also polyembryony (several embryos in one seed). The endosperm also develops without the usual double fertilization. The apogamous embryos have already been found in the flower buds of several species, so that cross-pollination is excluded.

In African species there is often normally developed pollen, but even here there is already apomictic embryo sac development. Almost all Central European species reproduce agamosperm. Examples of native, sexually reproducing species are Alchemilla pentaphyllea and a few species of the species group Alchemilla hoppeana agg.

Spread

The whole fruiting blossoms serve as spreading units ( diaspores ). The ripe nuts stay in the goblet until it weathers. The sepals and hairy parts of the flower serve to ensure that the diaspore adheres to the fur of animals ( epizoochory ). Wet fruits also stick to shoes and animal hooves. For rock-dwelling species even common ravens are given as distributors.

Phenology

The Alchemilla species do not really hibernate, species of the Alpinae section often overwinter with fully developed leaves, and Caucasian species often form leaves as early as January. The inflorescences are often not formed in the same vegetation period ( sylleptic ) as the bracts from whose axils they arise. Usually they arise in the next growing season (opistholeptic). The axes of the inflorescences then arise below the leaf rosette. The sylleptic flower formation usually takes place in autumn, in Central Europe the flowering is then often interrupted by winter or postponed to spring at all. In mild winters, species can continue to bloom in winter. The species behave like short-day plants : they create the inflorescences in the short day, cannot bloom in the short day due to the low temperatures and therefore postpone blooming in the warmer long day. During the long day only vegetative side shoots are formed.

Diseases and Herbivores

Often occur at Alchemilla TYPES virus diseases , which are transmitted by sucking insects. Of importance are rust fungi of the genus Trachyspora , which can also cause the plants to die, and in Africa the rust fungus Joerstadia . The powdery mildew Sphaerotheca aphanis particularly affects species with soft leaves.

The only known flowering plant parasitic on Alchemilla is Quendel silk ( Cuscuta epithymum ).

Among herbivores , bladder feet , cicadas , aphids and caterpillars are worth mentioning. Owl caterpillars (Noctuidae) cause plants to die by eating their roots.

distribution

The genus Alchemilla is almost exclusively found in the Old World and especially in the mountains. In the Himalayas only a few species are represented. In the north of Eurasia it also occurs in the plain. It is absent in arid regions. The mountains of East Africa represent a center of diversity in terms of growth forms and kinship groups. In the temperate areas there is a center in the Middle East, which should be home to around 500 species. In the area north of the Caucasus around 60 species occur, in Siberia 40 and in Central Asia around 20. In Japan one species is endemic . In the Carpathians there are around 70 species (40 endemic), in the Alps 150, on the Iberian Peninsula around 50. Four species reach as far as Arctic North America ( Greenland , Labrador , Newfoundland ), a species related to European clans grows in the Atlas . In the north the area extends up to the 70th parallel, in the Alps the genus rises up to 3200 m, in the Elburs Mountains up to 3760 m. Several Central European species, particularly Alchemilla xanthochlora , have been introduced to North America, New Zealand, and Australia.

In Central Europe, have areas that have remained unglaciated during the last ice age, the highest species richness: southern Jura , Savoie , Lower Valais , Friborg Limestone Alps , valleys where (Wallis), Aosta Valley , Hohe Tauern , the Dolomites and Styrian Prealps . Most endemics are found in these areas. The highest number of species in Europe is reached on the Gemmialp in Valais, where around 50 species occur on two square kilometers.

Site conditions

The Alchemilla species require a good water supply, lots of light and protection from snow in winter or mild winters. The seeds are frost and light germs. Mycorrhiza was observed in the shrubby species . The high alpine species reproduce mainly vegetatively , as the fruits do not ripen in most years.

Lady's mantle often form mass deposits on fertilized meadows. These fast-growing species are well tolerated by walking and, with a good water supply, can quickly utilize the available nitrogen. This means that they are quite competitive on these locations, especially on poultry pastures.

Systematics

The genus Alchemilla is placed within the family of the rose family (Rosaceae) in the subfamily Rosoideae and in the tribe Potentilleae. Within this it is sometimes placed in a separate subtribe Alchemillinae together with the genera Lachemilla and Aphanes . Some authors have listed these three genera as sub-genera of Alchemilla , and some have just put Lachemilla alternately to one of the other two genera.

System of the overall genre

The system of the overall genre is largely based on the work of Werner Rothmaler from the 1930s. He divided the genus into seven sections based on morphological features . In 2004, Notov and Kusnetzova raised some of Rothmaler's subsections to sections, so that there are now ten sections according to this system. Except for the last two sections, which are Eurasian, all are limited to the tropics and subtropics:

- Section Subcuneatifoliae

- Geraniifoliae section

- Section Grandifoliae

- Longicaules section

- Section Villosae (Rothm.) Notov

- Section Pedatae (= Rothmaler's subsections Pedatae and Cryptanthae )

- Section Schizophyllae (Rothm.) Notov

- Section Parvifoliae

- Section Brevicaules Rothm.

- Chirophyllum subsection

- Subsection Heliodrosum

- Subsection Calycanthum

- Section Pentaphylleae Buser ex Camus

Systematics of the European clans

At least for the European genres there is a more modern system from Sigurd Fröhner , which has replaced the two sections Brevicaules and Pentaphylleae in the sense of Rothmaler. In Eurasia there are four main groups of alchemils, which have the rank of independent sections. The four main groups are characterized by complexes of characteristics (which are identified with the first letter of the section):

- Section Erectae (E): They are tall semi-shrubs with a long-lived basic axis. The stipules are fused on the petiole. The flower cup is short and the sepals and outer sepals long.

- Ultravulgares section (U): They are medium-sized subshrubs with a short-lived basic axis. The stipules are not fused with the petiole. The flower cup is long, the sepals short, the outer sepals even shorter.

- Section Alpinae (A): They are silky, hairy dwarf shrubs with a long-lived main axis. The stipules are membranous, fused to each other on the petiole and opposite. The leaves are deeply divided, the inflorescences are coiled , the outer calyx is small.

- Section Pentaphylleae (P): They are bald or slightly stiff-haired subshrubs to perennials with a short-lived main axis. The stipules are thick and hardly overgrown. The leaves are divided to the base and roughly toothed. The flowers are in sham umbels. The outer cup is small or absent.

All European species are believed to be of ancient hybridogenic origin. This results from morphological, anatomical, embryological, ecological and chorological data. This process has long been completed, at least since the period before the last ice age. For example, there are no known post-glacial endemics. In addition, all of the morphological conceivable parent species of the individual hybrid species are highly polyploid and apomictic, so they cannot be the parents. Due to the apomixis as a genetic barrier, the individual species are effectively separated from one another if they grow together with closely related species in the same location.

More common than these main groups are species with mixed characteristics. These are secondary, hybridogenic clans . They therefore have the characteristics of two or three of the main groups. 13 of the theoretically possible 15 feature complexes have also been implemented and Fröhner also lists them in the range of sections (the feature complexes from the main groups in brackets). The assignment of the species follows Fröhner (1995), with changes to the section assignment and new species from Fischer (2008) being adopted (for species of the sections with their own article, see there):

- Section Erectae (E)

- Section Alchemilla (EU) (Species previously to Alchemilla vulgaris agg. )

- Section Coriaceae (EUP) (species earlier to Alchemilla vulgaris agg.)

- Section Calycinae (EP) (species formerly to Alchemilla fissa agg.)

- Slashed lady's mantle ( Alchemilla fissa Günther & Schummel )

- Julisch lady 's mantle ( Alchemilla venosula Buser ) (including Alchemilla gracillima Rothm. )

- Section Decumbentes (UP) (species formerly to Alchemilla vulgaris agg.)

- Lying lady's mantle ( Alchemilla decumbens buser )

- Long-eyed lady's mantle ( Alchemilla flaccida buser )

- West Tyrolean lady's mantle ( Alchemilla hirtipes Buser )

- Rotscheidiger lady 's mantle ( Alchemilla rubristipula buser )

- Thin lady's mantle ( Alchemilla tenuis Buser )

- Section Ultravulgares (U) (species formerly to Alchemilla vulgaris agg.)

- Section Plicatae (UAP) (species formerly part of Alchemilla vulgaris agg., Part of Alchemilla hybrida agg.)

- Pubescentes Section (WP)

- Paiches lady's mantle ( Alchemilla paicheana (Buser) Rothm. )

- Splendentes Section (EUA)

- Deceptive lady's mantle ( Alchemilla fallax buser )

- St. Gingolph lady 's mantle ( Alchemilla gingolphiana S.E. Fröhner )

- Shimmering lady's mantle ( Alchemilla splendens Christ )

- Flabellatae Section (EAP)

- Spitz Bloom lady's mantle ( Alchemilla acutata Buser )

- Bona lady's mantle ( Alchemilla bonae S.E. Fröhner )

- Carniola lady's mantle ( Alchemilla carniolica (Paulin) Fritsch )

- Fan lady's mantle ( Alchemilla flabellata Buser )

- Swiss lady's mantle ( Alchemilla helvetica Brügger )

- Unterwalliser lady 's mantle ( Alchemilla infravallesia (Buser) Rothm. )

- Jaquet's lady 's mantle ( Alchemilla jaquetiana Buser )

- Kerner's lady's mantle ( Alchemilla kerneri Rothm. )

- Matrei lady 's mantle ( Alchemilla matreiensis S.E. Fröhner )

- Radiant lady 's mantle ( Alchemilla radiisecta Buser )

- Section Glaciales (AP) (species formerly mainly to Alchemilla vulgaris agg.)

- Section Alpinae (A) (species formerly part of Alchemilla vulgaris agg., Part of Alchemilla conjuncta agg.)

- Section Pentaphylleae (P) with only one species:

- Snow Lady's Mantle ( Alchemilla pentaphyllea L. )

The traditional division of the whole-leaf species according to their hairiness into several series ( Glabrae, Subglabrae, Splendentes, Hirsuta, Hteropodae, Pubescentes ) has been replaced by the above structure. The subdivision into groups of species (such as Alchemilla vulgaris agg.) Was also given up and their species were assigned to the above sections. The sections indicate the species groups from which their species come.

Molecular Phylogenetics

DNA sequence analyzes of 100 species of the three genera Alchemilla , Lachemilla and Aphanes , which included all sections, showed that Lachemilla and Aphanes are monophyletic, i.e. natural relatives. However, Alchemilla fell into two clades . The relationships are shown in the following cladogram :

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Afromilla clade |

|||||||||||||

|

|

The species of the genus Alchemilla are divided into the Eurasian species (Eualchemilla clade) and the African species (Afromilla clade). The Eualchemilla clade is divided into two subclades, the Lobed clade with species with lobed leaves and the Dissected clade with predominantly species with divided leaves. Within these groups there was no longer any breakdown into further clades.

The genus Alchemilla in the classical sense is thus paraphyletic . Gehrke et al. a. (2008) propose to incorporate Aphanoides and Lachemilla into Alchemilla . They consider the separation of Alchemilla in two genera to be inappropriate due to the lack of morphological separating features. According to Gehrke, maintaining the subtribe Alchemillinae is not appropriate, since this would make the Subtribus Fragariinae paraphyletic.

use

The whole-leaved Alchemilla species make good forage. They are also eaten fresh by cattle, less often by poultry. The alpine dwarf shrubs, on the other hand, are considered pasture weeds, as they often form mass populations and are only eaten by sheep and goats, not by other cattle.

In folk medicine , the types are used to treat wounds, bleeding, gynecological diseases, ulcers, abdominal pain, kidney stones, headaches and other ailments. All Central European species are used as folk medicinal plants and as cult or magic plants. Popularly, women's coats only differentiate between the (hairy) “silver coat” or “Alpen-Sinau” and the rather bald “lady's coat”.

Hairy Alchemilla species are used as ornamental plants in rock gardens and parks . Examples are Alchemilla mollis , which can easily degenerate into a weed, Alchemilla speciosa and Alchemilla conjuncta (often referred to as Alchemilla splendens ).

Names and common names

The name Alchemilla is derived from the term alchemy and was first used in 1485 in the Garden of Health . It means something like little alchemist . The alchemists used the guttation drops on the leaves for their experiments.

The German common name "Frauenmantel" refers to the similarity of the pleated leaves with the mantle on medieval depictions of Mary . In Nassau and the Bohemian Forest it is also called “Liebfrauenmantel”. Alchemilla alpina and similar species are called "Silbermänteli", "Silberchrut" or similar. Names like “Zugmantel” (in Silesia ), “Krausemäntelchen” (Upper Harz) and “Röckli” (Switzerland) refer to the pleated leaves . Names such as “Hiadl” (Bohemian Forest), “Dächrut” (Switzerland) or “Regendächle” (Swabia) allude to the shape of the leaf. The guttation drops led to the name "Sinau" (from Sinn-Tau = Immertau), "Taublatt", "Taubecher" etc. These drops were also compared with the blood drops of Jesus crucified or the tears of Mary. The leaves are also compared to goose feet and lion feet. According to their location on pastures, they are also referred to as "pig rose" ( East Prussia ) and "goose green". Their use as a medicinal plant was reflected in names such as "Ohmkraut", "Wundwurz" (Carinthia), "Motherwort", "Milk herb", "Frauentrost", "Aller Fraue Heil" and "Allerfrauenheil".

Botanical history

The genus Alchemilla was established by Carl von Linné in his work Species Plantarum in 1753 . As the first non-European species, Thunberg discovered Alchemilla capensis in 1792 ( first description 1823). The first to make classifications within the genera was Robert Buser in 1892, who also first described many European species. The system that is still most widespread today was developed by Werner Rothmaler in the 1930s, who refined Buser's system. In the 1990s, Sigurd Fröhner completely revised the structure of the European species for the "Flora of Central Europe" and "Flora Iberica" and developed the section structure shown above. In 2004, Notov and Kusnetzova revised the structure of the African sections. In 2008 the first molecular phylogenetics by Gehrke u. a. published.

history

The leontopodium or pedeleonis of Dioscurides , Pliny (both 1st century) and Pseudo-Apuleius (4th century) was interpreted as a lady's mantle by the garden of health in the 15th century and by the fathers of botany in the 16th century. The following healing effects and characteristics of the leontopodium were stated by the ancient and late ancient authors:

- acts as a love spell (Dioscurides),

- evokes crazy dreams (Pliny),

- is used to treat tumors (Dioscurides),

- pulls out penetrated objects (Pliny).

As synaw , the lady 's mantle was for the first time safely tangible in the late medieval book of the distilled waters of Gabriel von Lebenstein . Lebenstein recommended the internal use of the distillate from the lady's mantle for those who “spoke inside”.

In the Mainz Garden of Health of 1485, the chapter alchemilla synauwe was illustrated for the first time with a lifelike depiction of the woman's coat. It was here that the Latin name alchemilla appeared for the first time .

In his small distilling book from 1500 Hieronymus Brunschwig named the following applications for the distillate from the whole plant (root and herb):

- externally to extinguish "bad heat" in wounds,

- placed with a cloth on the breasts of women so that they become "strong and straight",

- inwardly for "broken lüt".

The fathers of botany ( Brunfels , Bock and Fuchs ) adopted these recommendations for use in their herbal books.

From the 16th to the 19th centuries, however, lady's mantle was only used in folk medicine.

In 1986, Commission E of the former Federal Health Office published a (positive) monograph on lady's mantle herb, in which “slight unspecific diarrheal diseases” are given as an indication . There is a (zero) monograph on Alpine women's mantle herb from 1992; there is no evidence of its effectiveness in the claimed areas of application (as a diuretic, anticonvulsant, cardiac support agent, in women’s disease). However, the application does not pose a risk.

Historical illustrations

Pseudo-Apuleius Leiden 6th century

Vitus outlet 1479

Garden of Health 1485

Otto Brunfels 1532

Leonhart Fuchs 1543

Hieronymus Bock 1546

supporting documents

Unless specified under individual evidence, the article is based on the following documents:

- Sigurd Fröhner: Alchemilla . In: Hans. J. Conert et al. (Ed.): Gustav Hegi. Illustrated flora of Central Europe. Volume 4 Part 2B: Spermatophyta: Angiospermae: Dicotyledones 2 (3). Rosaceae 2 . Blackwell 1995, pp. 13-242. ISBN 3-8263-2533-8

- B. Gehrke, C. Bräuchler, K. Romoleroux, M. Lundberg, G. Heubl, T. Eriksson: Molecular phylogenetics of Alchemilla, Aphanes and Lachemilla (Rosaceae) inferred from plastid and nuclear intron and spacer DNA sequences, with comments on generic classification. In: Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution , Volume 47, 2008, pp. 1030-1044. doi : 10.1016 / j.ympev.2008.03.004 ( online ) (Molecular Phylogenetics)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Alexander A. Notov, Tatyana V. Kusnetzova: Architectural units, axiality and their taxonomic implications in Alchemillinae. In: Wulfenia , Volume 11, 2004, pp. 85-130. ISSN 1561-882X

- ↑ B. Gehrke, C. Bräuchler, K. Romoleroux, M. Lundberg, G. Heubl, T. Eriksson: Molecular phylogenetics of Alchemilla, Aphanes and Lachemilla (Rosaceae) inferred from plastid and nuclear intron and spacer DNA sequences, with comments on generic classification . Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, Volume 47, 2008, pp. 1030-1044. doi : 10.1016 / j.ympev.2008.03.004

- ^ A b Manfred A. Fischer, Karl Oswald, Wolfgang Adler: Excursion flora for Austria, Liechtenstein and South Tyrol . 3rd, improved edition. Province of Upper Austria, Biology Center of the Upper Austrian State Museums, Linz 2008, ISBN 978-3-85474-187-9 , p. 489 .

- ^ S. Fröhner: Alchemilla , 1995, p. 33.

- ↑ Pedanios Dioscurides : 1st century, De Medicinali Materia libri quinque. Translation. Julius Berendes . Pedanius Dioscurides' medicine theory in 5 books. Enke, Stuttgart 1902, pp. 436–437 (Book IV, Chapter 129): leontopodion (digitized version )

- ↑ Pliny : Naturalis historia . Book XXVI, Chapter XXXIV (§ 52): leontopodion. Online edition Chicago (digitized version) ; Translation Külb: (digitized version )

- ↑ Pseudo-Apuleius 4th century print 1481, chapter 7: Herba pedeleonis digitized

- ^ Ernst Howald and Henry E. Sigerist : Antonii Musae De herba vettonica, Liber Pseudo-Apulei herbarius, Anonymi De taxone liber, Sexti Placiti Liber medicinae ex animalibus. , Teubner, Leipzig 1927 (= Corpus medicorum latinorum , Vol. IV)

- ↑ Howald - Sigerist 1927 (digitized version)

- ↑ Kai Brodersen : Apuleius, Heilkräuterbuch / Herbarius , Latin and German. Marix, Wiesbaden 2015. ISBN 978-3-7374-0999-5

- ↑ Gabriel von Lebenstein , 14th / 15th century. On the distilled waters. Clm 5905, Bavarian, 2nd half of the 15th century. Sheet 55v: Synaw water has the virtue, whoever speaks necessarily, trinck synaw water is what he has in the (digitized version ) (Gerhard Eis, Hans J. Vermeer 1965, 68– 69)

- ↑ Cpg 545, Nuremberg 1474, sheet 106r-v: Synaw water for use Item Synaw water is good when it is easy to break whoever is supposed to drink in the morning and in the evening He may also drink his pleasure and a cloth drunk on top of it and outside too placed where the pruch is and to be pounded and stuck so it heals ahead young lewt or newe bruch Vnd whether ymant yn ÿm a little too vallent het the drink be it heals to the wounds Item such a wonder is the boiling synaw water jn wine and wash the wounds do with vnd lay a wolves from a lay judge who open up with a pawmöl vnd drink the water in the evening and in the morning So it heals from the ground up in a short time you should be but not drink alveg it makes you the derm to sampled (digitalized)

- ↑ Gerhard Eis: Gabriel von Lebenstein's treatise "From the distilled waters". In: Sudhoffs Archiv 35 (1942), pp. 141–159. (Edition)

- ↑ Gart der Gesundheit . Mainz 1485, chapter 32: alchimilla synauwe digitized

- ↑ Hieronymus Brunschwig : Small distilling book . Strasbourg 1500, sheet 104r digitized

- ^ Otto Brunfels : Contrafeyt Kreüterbuch. Strasbourg 1532, p. 182: Synnaw or our Frawen mantel digitized version

- ↑ Hieronymus Bock : New Kreütter book. Strasbourg 1539, Book I, Chapter 174: Synaw digitized

- ^ Leonhart Fuchs : New Kreütterbuch. Strasbourg 1543, chapter 234: Synaw digitized

- ↑ Jacobus Theodorus : Neuw Kreuterbuch. Nicolaus Basseus, Franckfurt am Mayn 1588, pp. 308–312: Sinnaw (digitized version )

- ↑ Nicolas Lémery : Dictionnaire universel des drogues simples. Laurent d'Houry, Paris 1699, p. 21: Alchimilla (digitized) . Translation. Complete material lexicon. Initially drafted in French, but now after the third edition, which has been enlarged by a large [...] edition, translated into high German / By Christoph Friedrich Richtern, [...]. : Johann Friedrich Braun, Leipzig 1721, Sp. 31–32: Alchimilla (digitized version )

- ^ William Cullen : A treatise of the materia medica. Charles Elliot, Edinburgh 1789, Volume II, p. 32 (digitized version) . German. Samuel Hahnemann . Schwickert, Leipzig 1790, Volume II, p. 39 (digitized version)

- ↑ Monograph of Commission E online .

- ↑ Monograph of Commission E online .