History of Louisiana

The history of Louisiana relates to the history of the US state of Louisiana, which was admitted to the Union in 1812 . Part of its historical heritage are the Indian cultures and advanced civilizations that existed between 3400 BC. Chr. And subjugation by Europeans from 1700 n. Chr. Existed in the region of the later Louisiana and several impressive archaeological leaving certificates. The prehistory of the state of Louisiana in the narrower sense includes the phase of French colonial rule between 1700 and 1763, to which Louisiana owes its name and a number of remnants of French culture and language, as well as a short phase of Spanish colonial rule between 1763 and 1800, during which the French element evolved through immigration the former French Canada . A three-year French colonial interlude followed before the USA bought the entire French colony of Louisiana , of which today's Louisiana was only a small part, in the so-called Louisiana Purchase from France.

The dark chapter of slavery determined the history of the Afro-American part of the population of Louisiana - and thus half of the population - from the French colonial era to the American Civil War 1860-1865, which the state of Louisiana on the side , regardless of changing colonial masters or the status as a US state of the defeated Confederate States of America . The struggle for the civil rights of Afro-Americans, whom z. B. the right to vote was withheld, the civil rights activists in Louisiana led victorious particularly in the 1950s to 1960s.

The Native American history of Louisiana did not end with the destruction of the civilizations that existed before the arrival of Europeans, but continued as a history of displacement, adaptation and resistance of a population group that now makes up just 0.6% of the total population of the state.

Indian early history

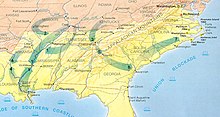

In the archaeological occupied last 6000 years developed in the area of today's Louisianna some Indian cultures, their distribution is often over both sides of the Mississippi Valley and into the neighboring state of Mississippi stretched into it. Basically, they were related to major developments in Indian cultures throughout the south and southeast of the USA, which in turn had certain connections to the cultures of the northern Mississippi and Ohio valleys (e.g. the Hopewell culture ) as well as pre-Columbian Central America .

Archaic period

In Louisianna there are several of the earliest so-called mounds , large pyramidal, semicircular or snake-shaped embankments , as the most impressive evidence of the Archaic Period of the North American Indians . The oldest mounds and thus the oldest known structures in North America are located in Louisiana. The central archaic mound systems include Watson Brake and Frenchman's Bend near what is now Monroe (Louisiana) . They are dated to an age of around 5500-5000 years. Most famous is the Poverty Point complex at the end of the Archaic Period. The culture he named spanned parts of Louisiana and the neighboring states. It probably had its peak around 1500 BC. BC, making it one of the oldest or even the oldest complex civilizations in the USA.

Woodland period

The Woodland Period that followed the Archaic Period lasted in much of Louisiana from about 1000 BC. until 1000 AD and differed from the previous one in the greater spread of ceramics and the increasing sedentariness and use of agriculture. Although the focus of the period was still on the nomadic way of life of hunters and gatherers , semi-permanent settlements also emerged. In its middle phase, the Hopewell culture developed north of Louisiana , which also had a great influence on the cultures of Louisiana.

Mississippi period

The Mississippi culture , which originated on the northern Mississippi, influenced various cultures of Louisiana, particularly the Plaquemine culture between about AD 1200 and 1400 and the Caddo culture . The cultivation of maize spread. As the only Indian culture north of Mexico , the Mississippi culture built fortified cities, the social structure was strongly hierarchical and parallels to the society of the Aztecs of Mesoamerica are obvious.

First European-Indian contacts

In 1528, Pánfilo de Narváez, the first European to reach the mouth of the Mississippi. In 1542, Hernando de Soto's expedition went through the north and west of Louisiana, met the Caddo and Tunica there and followed the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico .

Upon their arrival in Louisiana lived some Indian peoples, such as the Atakapa , Appalousa , Acolapissa , Tangipahoa , Chitimacha , Washa , Chawasha , Yagenechito belonging to the Choctaw belonging Bayougoula , Quinipissa , Mougoulacha also to the Choctaw belonging Houma , Okelousa to Avoyel and Taensa , Tunica , Koroa , Caddo , Adai , Natchitoches , Yatasi , Nakasa , Doustioni and Quachita belonging to the Natchez , some of which have left traces in the form of place names, e.g. the tunica, tangipahoa or the natchitoches.

The Spanish conquistadors did not find the easy fortune they had hoped for, as others had found before and after them in Mexico or Peru . They were therefore not interested in permanent colonization or the establishment of bases in Louisiana.

Colonial phases

French colonization from 1682

In 1682 Robert Cavelier de La Salle reached Louisiana and the mouth of the largest river in North America, coming from the north over the Mississippi. It started in the French colony of New France , which up to this point comprised roughly what is now the French-speaking part of Canada . He took possession of the vast area between the Great Lakes and the Gulf of Mexico for France and named it Louisiana in honor of the French King Louis XIV . This indirectly gave him the name of what would later become the state of Louisiana, which only covers a fraction of the area of the French colony of Louisiana that is now emerging .

In 1699, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville founded Fort Maurepas near today's Biloxi as the first French base on the southern Mississippi in what is now the state of Mississippi . Founded in 1714, Natchitoches became Louisiana’s first permanent European settlement. In 1718, today's New Orleans was founded by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville under the name La Nouvelle-Orléans ("The French Orleans", in honor of Philip II, Duke of Orléans ) . After Mobile ( Alabama ) and Biloxi ( Mississippi ), New Orleans became the capital of Louisiana in 1722.

Early slavery

The Scottish-born French finance minister and head of the Mississippi company, John Law , made the far-reaching decision in 1717 to import black slaves into Louisiana to promote the plantation economy there. They were used for work on the tobacco plantations that are now being created . In 1719 the first ships with slaves reached New Orleans. From 1719 to 1753 6000 slaves from Africa were brought to the colony, whose legal status, like in the other French possessions, was regulated by the Code Noir .

Indian resistance

Very soon the French colonizers encountered resistance from the native Indians. In particular against the Natchez Indians they waged four wars from 1710 until the end of their rule in 1763. The bloodiest of these wars was the 1729 Natchez Uprising , in which the Natchez and their allies destroyed Fort Rosalie , France , killing over 200 colonists - including the entire adult male population - and capturing more than 300 women, children and slaves. The Natchez were often split into a French-friendly and an anti-French part. The background of these armed conflicts were mostly the expulsions of Indians by the French who wanted to use an area for tobacco cultivation. The conflicts spread to other Indian peoples such as the Chickasaw , but took place mainly outside of today's Louisiana in neighboring Mississippi. Often the Indians were supported by the black slaves of the French.

A succession of other wars between the French and Indians outside of modern Louisiana became decisive for the country's future. The so-called French and Indian War 1756–1763 took place between the British and French and the Indians allied with them mainly in the Great Lakes area and ended with the defeat of the French and the sale of their Louisiana colony to the Spanish in 1763.

Spanish interlude and French immigration

In 1762 the French gave up all their colonial ambitions in North America and promised their colony Louisiana to Spain in the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau . In Paris Peace of 1763 this change of power was confirmed. In the almost four decades of Spanish rule over Louisiana that followed, the French element of this area was reinforced by two waves of immigration. In the 1760s the so-called Acadians came to Louisiana. The Acadians were French who originally settled in Canadian Acadia , which had become British as early as 1713. From 1750 onwards there were uprisings sponsored by France, which ended in 1755 with the extensive expulsion of the French from Acadia. After often years of wandering, a large number of these refugees came to Louisiana, now in Spain. They formed the core of today's French-speaking population group in Louisiana, the Cajuns . Joseph Broussard was the leader of the first group of Acadians to arrive in Louisiana: after being imprisoned by the British in Acadia, he was given permission to relocate with a group of 200 people to the British Caribbean island of Dominica , from where they finally emigrated to Louisiana in 1765 .

The outbreak of the French Revolution brought another group of French to Louisiana with royalist -minded refugees from the 1780s .

Germans also settled in Louisiana, Spain. From 1768 they arrived in what was then the Côte des Allemands , now known as the German Coast , and soon adopted the French language, thereby strengthening the country's French element.

The Spanish immigration consisted predominantly of the settlers from the Canary Islands , called Isleños , who came to Louisiana between 1778 and 1783.

The free as well as the unfree non-Indian population grew considerably during the Spanish period. 1763 lived between New Orleans and Pointe Coupee (north of Baton Rouge ) 3654 free and 4598 slaves. According to the 1800 Census, there were 19,852 free slaves - now including West Florida - and 24,264 slaves in lower Louisiana, which roughly comprised the present-day states of Louisiana, Mississippi and Arkansas . Even if this information is not as exact as it sounds, it does show that black slaves were already in the majority here at this time and had a strong influence on the local culture.

French again and Louisiana Purchase

On October 1st, 1800 Spain and Napoleon Bonaparte's France signed the quietly prepared Third Treaty of San Ildefonso . Spain, dependent on France, gave Louisiana back to France. Napoleon associated it with ambitions to rebuild a great French colonial empire in North America. However, he already failed in the attempt to recapture the rebellious, formerly French Caribbean island of Haiti , on which the former slaves had achieved their freedom and independence a few years earlier through the Haitian Revolution . This defeat led Napoleon to bury his American plans and sell Louisiana to the young United States of America .

American Louisiana

The Louisiana Purchase and the Setting of Louisiana's Boundaries

The Louisiana Purchase , the purchase of the French colony of Louisiana, was the largest property purchase in history. The land purchased covered more than a quarter of what is now the United States, a multiple of the state of Louisiana, and doubled the territory of the United States at the time.

Originally, President Thomas Jefferson only planned to purchase the city of New Orleans from France. The Americans had had the “right to settle” here since 1795 and the Spanish had permission to use the city's port. The sale to the French made him fear that these rights were being jeopardized. It was only in Paris that the American negotiators who were supposed to negotiate the purchase of New Orleans received the offer to buy the entire colony of Louisiana and accepted this offer.

Now revenge itself, however, that the handing over of Louisiana by the Spaniards to the French was not based on an exact definition of the borders of Louisiana. A disagreement arose between the US and Spain over the boundaries of the purchased area. According to the Spaniards, Louisiana consisted roughly of the north of today's Louisiana and a narrow strip in the middle of the state, as well as the western half of the modern states of Arkansas and Missouri. According to the Spanish representation, almost half of today's state of Louisiana would not be included in the purchase and both its southeast and southwest would be Spanish. The United States, on the other hand, considered all of present-day Louisiana to be theirs. They were also divided about West Florida , a strip of land between the Mississippi and Perdido rivers .

After a revolt in West Florida, the United States annexed the area in 1810 and divided it between the present-day US states Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida, thus defining the eastern border of Louisiana.

The western border of Louisiana was already disputed between the French and the Spanish, by buying Louisiana, the United States inherited the conflict. In 1805, after unsuccessful negotiations, Spain broke diplomatic relations with the United States and between October 1805 and October 1806 there were small skirmishes in the disputed area around the Sabine River . There were also rumors that both sides were gathering troops near the disputed area. To defuse tensions, it was agreed to regard the disputed region as a neutral area, which resulted in the Sabine Free State in western Louisiana , also known as the Neutral Ground , Neutral Strip , Neutral Territory or No Man's Land of Louisiana . The agreement between the two states stipulated that the neutral area was forbidden for soldiers as well as for settlers. Settlers on both sides did not obey this ban, however, and the lawless area attracted deserters, political refugees, adventurers and a wide variety of criminals. In 1810 and 1812 the two governments jointly sent military expeditions to the area to drive out the outlaws.

It was not until the Adams-Onís Treaty, ratified by the USA in 1821, that the controversial issues in the West were settled through a mixture of exchange of territory and purchase by the USA. The borders of Louisiana, which are still valid today, were thus defined in the west as the border between the USA and the then Spanish Texas.

New Orleans Territory

The territories acquired by the Louisiana Purchase were not given the status of states, but of "territories" ( organized incorporated territories ) of the USA. They were recognized as state territory of the USA ("incorporated") and with a government recognized by law of the US Congress ("organic act") as legal representative, they were considered "organized". The Orleans Territory , forerunner of the later state of Louisiana, was created on October 1, 1804 by the Organic Act of March 26, 1804 and divided into 12 counties by the Territorial Parliament on April 10, 1805.

William Charles Cole Claiborne became governor of the Territory and remained so between 1804 and 1812, the entire time the Territory was in existence.

In 1811 there was the largest slave revolt in US history in the New Orleans Territory not far from the capital New Orleans ; the German Coast Uprising . Up to 500 slaves rose on the German Coast 40 miles from New Orleans and marched within 20 miles of the city. It took all of the territory's military might to suppress the uprising.

Admission into the Union and development up to civil war

On April 30, 1812, the Orleans Territory was incorporated into the United States under the name Louisiana as the 18th state. To avoid confusion, the Louisiana Territory to the north was renamed Missouri Territory in June of the same year .

In the British-American War 1812-1814, Louisiana became a theater of war. Even after the official end of the war, the Battle of New Orleans took place in January 1815 , in which the Americans defeated the British invading forces. Only shortly afterwards did both sides find out about the peace agreement.

Louisiana's capital, New Orleans, experienced a significant economic boom and became the USA's most important port for the export of cotton and sugar . In 1840 New Orleans had the largest slave market in the United States, was - in relation to the white population - one of the wealthiest cities in the country and the third largest city in the United States.

As a result of the Indian resettlement , Louisiana experienced an economic boom in the 1830s . This was also promoted by the debt-financed expansion of the transport routes. In 1840, Louisiana’s national debt had risen significantly. Louisiana declared national bankruptcy in the wake of the economic crisis of 1837 1840 and only partially serviced its government bonds .

In 1849 Baton Rouge became the capital of Louisiana for several years.

At 18,647, Louisiana had the largest number of free blacks of any US state immediately before the Civil War. Most of them lived in the southern half of the country, particularly New Orleans, and many of them were middle class and educated.

According to the 1860 census, 331,726 people were enslaved. With that almost 47% of the state population were 708,002 slaves.

The construction and expansion of the dyke system was a crucial prerequisite for Louisiana's economic progress, in particular for the expansion of the areas for the export products sugar and cotton. In 1860, in Louisiana 1,190 km of levees along the Mississippi and a further 720 km at its tributaries were mostly built by hand.

Louisiana in the Civil War

When the American Civil War broke out in 1861, the interests of those in power in the state were clear. Louisiana's economy was based on slave labor. After the election of Abraham Lincoln as President, it declared its exit from the Union on January 26, 1861 and immediately joined the Confederate States of America . This made Louisiana one of the six founding states of the Confederation. The Union states' strategy of dividing the southern states in half by occupying the Mississippi Valley led to an early conquest of the state of Louisiana. In the second year of the war, on April 25, 1862, New Orleans was taken by the troops of the north, and the capital of Confederate Louisiana was then moved to Shreveport . In 1865 the Confederate States capitulated.

Reconstruction and denial of civil rights for blacks

Like the other states of the defeated Confederation, Louisiana was placed under military administration and declared, together with Texas, as Military District 5 under the authority of Major General Philip H. Sheridan . Then began the reconstruction phase , the reshaping of the conquered South according to the ideas of the North, in particular the implementation of the liberation of slaves and the civil rights of the black population, the removal of the supporters of the Confederation from political offices and the drafting of a new constitution for the state. Resistance to the transformation was put down militarily.

Three years later on July 9, 1868, Louisiana was re-admitted to the Union.

In 1874 the White League was formed in Louisiana , a racist organization comparable to the Ku Klux Klan . Later that year the Battle of Liberty Place broke out in New Orleans , in which 5,000 White League members fought with 3,500 Louisiana police officers and members of the Louisiana militia to obtain the ousting of the governor. Only through the deployment of soldiers from the north was the Union able to take power in the city again.

From the 1880s onwards, the leading Democratic Party in the whole of the south achieved the de facto denial of the right to vote for the black population, who made up about half of the total population. A new constitution that came into force in 1898 introduced requirements for the right to vote, such as a tax on registration as a voter, proof of place of residence and tests of writing skills, which led directly to the exclusion of large numbers of blacks. While 130,334 blacks and roughly the same number of whites were registered as voters in 1896, there were only a good 5,000 registered black voters in the entire state in 1900 and 730 in 1910. The so-called grandfather rights ensured that whites were exempt from discriminatory provisions such as the literacy test . The white democrats exercised an undisputed absolute rule well into the 20th century.

In 1923, Louisiana introduced universal “white” primaries , excluding African-Americans from the only crucial state-level election process under the circumstances of the de facto one-party state.

This persistent discrimination and the economic situation led between 1910 and 1930 to the first Great Migration ("Great Migration Movement") of African Americans from Louisiana and other southern states to the north or California (see History of the African American ).

The time of the Great Depression of the 1930s saw Louisiana under the leadership of the populist governor Huey Pierce Long , who maintained an extremely autocratic style of government and was murdered in 1935. His ideas of overcoming the economic crisis went beyond President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Deal .

He saw to it that the poll tax , one of the elements that prevented blacks from exercising their right to vote, was abolished , but the “white” primaries continued until 1944 and were eventually abolished by the US Supreme Court .

In 1948, just 1% of Louisiana's black population managed to get their vote.

Fight for civil rights

New ways were found to deny the black population the right to vote. Although civil rights movements worked hard to register black voters in New Orleans and the southern parish of Louisiana, where there was a long tradition of free, colored citizens, the percentage rose to only 5% between 1948 and 1952. By 1964 that number rose to 32%. However, the percentage of blacks registered as voters varied greatly: from 93.8% in Evangeline Parish to only 1.7% in Tensas Parish .

The ongoing discrimination led to a second major migration of blacks from Louisiana north and west, with the result that in 1960 the proportion of African Americans here had fallen to 32%.

The black civil rights movement enforced decisive anti-discrimination laws with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voters Act of 1965, and by 1968 nearly 59% of the eligible Louisiana black population were registered as voters. Today this proportion is around 70%, which is higher than the corresponding proportion in any other country in the south. In 1967 Louisiana was one of the last US states to be forced by the Supreme Court to change the prohibition on mixed marriage .

Hurricane Katrina

A turning point in the history of Louisiana in this millennium is Hurricane Katrina , which in 2005 broke the levees on Lake Pontchartrain and flooded the city of New Orleans. The natural disaster with 1,800 deaths developed into a scandal here, the victims were mostly black, assistance was partially omitted after allegedly helicopters had been shot at by survivors, an unknown number of the dead were victims of white vigilante groups and the racist background of media reports and failure to provide assistance the state was evident. In 2008 there were still 120,000 former residents of New Orleans, mostly black, scattered across the United States, some in emergency shelters.

literature

- Sophie White: Wild Frenchmen and Frenchified Indians. Material Culture and Race in Colonial Louisiana , University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

- Bennett H. Wall & John C. Rodrigue [Eds.]: Louisiana: A History. Wiley-Blackwell, 6th edition 2014. ISBN 978-1-118-61929-2 (Paperback)

Remarks

- ↑ factfinder.census.gov ( Memento of November 13, 2007 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Saunders, Joe W .; Almond, Rolfe D .; Sampson, C. Garth; Allen, Charles M .; Allen, E. Thurman; Bush, Daniel A .; Feathers, James K .; Gremillion, Kristen J. et al. (2005), "Watson Brake, a Middle Archaic Mound Complex in Northeast Louisiana," American Antiquity 70 (4): 631-668

- ^ Jon L. Gibson: "Poverty Point: The First Complex Mississippi Culture" ( Memento December 7, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), 2001, Delta Blues, accessed Oct 26, 2009

- ↑ texasbeyondhistory.net

- Jump up ↑ Sturdevent, William C. (1967): Early Indian Tribes, Cultures, and Linguistic Stocks , Smithsonian Institution Map (Eastern United States).

- ↑ explorenatchitoches.com ( Memento of the original from April 21, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo, Africans in Colonial Louisiana , p61

- ↑ quoted from: en: Louisiana (New France)

- ^ Charles F. Lawson: Archaeological Examination of Electromagnetic Features: An Example from the French Dwelling Site, a Late Eighteenth Century Plantation Site in Natchez, Adams County, Mississippi , 7.

- ↑ CA Pincombe and EW Larracy, Resurgo: The History of Moncton, Volume 1 , 1990, Moncton, p. 30th

- ↑ Andreas Hübner: The Côte des Allemands. A History of Migration in 18th Century Louisiana . transcript, Bielefeld 2017, ISBN 978-3-8376-4006-9 .

- ↑ Isleños - Erbe und Kultur (English) ( Memento of the original from May 7, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Hall, Africans in Colonial Louisiana , p. 279.

- ↑ "The Neutral Ground" chronology ( memento of the original from March 15, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , at Louisiana Places

- ^ "The Cabildo," at the Louisiana State Museum web site

- ↑ "Texas 1806" ( memento of the original from June 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Texas Archeological Society

- ↑ Nathan A. Buman, To Kill Whites: The 1811 Louisiana Slave Insurrection ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 505 kB), Louisiana State University, Aug 2008, p. 58, accessed 8 Dec 2008

- ^ Walter Johnson, Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market , Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999, p.2

- ↑ Historical Census Browser, 1860 US Census, University of Virginia ( Memento of the original from October 11, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed 31 Oct 2007

- ↑ Historical Census Browser, 1860 US Census, University of Virginia ( Memento of the original from October 11, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed October 31, 2007

- ^ The New York Times , Louisiana: The Levee System of the State, 10/08/1874 , accessed November 13, 2007

- ↑ Nicholas Lemann, `` Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War, '' New York, Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 2006, pp.76-77.

- ↑ Richard H. Pildes, Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon, Constitutional Commentary, Vol.17, 2000, p.12-13, Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- ↑ Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary , Vol. 17, p.12 , Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- ↑ Debo P. Adegbile, “Voting Rights in Louisiana: 1982-2006,” March 2006, pp. 6–7 ( Memento of the original from June 26, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed 19 Mar 2008

- ↑ Debo P. Adegbile, “Voting Rights in Louisiana: 1982-2006,” March 2006, p. 7 ( Memento of the original from June 26, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed 19 Mar 2008

- ↑ Debo P. Adegbile, Voting Rights in Louisiana: 1982-2006, March 2006, p. 7 ( Memento of the original from June 26, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed 19 March 2008

- ↑ Historical Census Browser, 1860 US Census, University of Virginia ( Memento of the original from October 11, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed 15 Mar 2008

- ^ Edward Blum and Abigail Thernstrom, Executive Summary of the Bullock-Gaddie Expert Report on Louisiana, Feb. 10, 2006, American Enterprise Institute, p. 1 ( Memento of the original from April 17, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed 19 March 2008