Austria-Hungary's South Tyrol offensive 1916

South Tyrol offensive 1916

| date | May 15 to June 16, 1916 |

|---|---|

| place | Border area Trentino - Veneto between the Adige Valley and Valsugana |

| output | Offensive fails |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf (Chief of Staff) |

Luigi Cadorna (Chief of Staff) |

| Troop strength | |

| 192 ½ battalions of 1056 guns |

98 battalions of 575 guns plus army reserves |

| losses | |

|

44,000 men, including 5,000 dead, 23,000 wounded, 14,000 sick, 2,000 prisoners |

73,142 men, including 5,764 dead, 24,423 wounded, 42,955 missing and prisoners |

1915

1st Isonzo - 2nd Isonzo - 3rd Isonzo - 4th Isonzo - Lavarone (1915-1916)

1916

5th Isonzo - South Tyrol offensive - 6th Isonzo - Doberdò - 7. Isonzo - 8. Isonzo - 9th Isonzo -

First Dolomites Offensive - Second Dolomites offensive -

Avalanche disaster

1917

10th Isonzo - Ortigara - 11th Isonzo - 12th Isonzo - Pozzuolo - Monte Grappa

1918

Piave - San Matteo - Vittorio Veneto

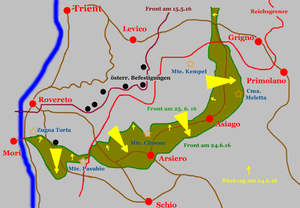

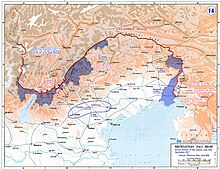

The South Tyrol offensive (also May offensive or spring offensive ) was an offensive operation of the Austro-Hungarian army in the First World War on the front against Italy . The offensive with the main thrust over the seven municipalities began on May 15, 1916. The purpose was to try to advance in the direction of Padua - Venice , to encircle the Italian forces east of the Piave and thus to neutralize or at least relieve the heavily pressed Isonzo front . The latter succeeded, if only temporarily.

Starting position

Even before Italy entered the war on May 23, 1915, the Austro-Hungarian High Command was forced, due to a lack of defensive forces, not to leave the front line at the imperial border, but to take it back on a shortened line. In the area of the seven municipalities, the entire Vallarsa with the unfinished fortress of Valmorbia , the Monte Pasubio , the Passo Pian delle Fugazze and almost the entire Terragnola valley with the Passo della Borcola were given up and the front was moved here to the line south of Rovereto , Monte Ghello, Northern edge of the Terragonaltal, Finocchio, Serrada plant and further along the fortification line to the Vezzena post , from there descending into the Valsugana near Novaledo .

On May 24th, the first massive Italian attacks began with artillery and later also with infantry against the fortress bar on the high plateau of Folgaria / Lavarone. In particular in the Lavarone section with the three fortifications Lusern , Verle and Vezzena, several intensive attempts were made to break through, which were supported by the k. u. k. Troops of the second contingent ( Landsturm , Standschützen , March battalions ) could only be turned away with great difficulty.

Instead of strengthening this section of the front and letting the Italians keep running against it with very high losses, it was believed that this danger had to be averted by a counterattack. Strengthened by the victories in Russian Poland , against Serbia and the defensive successes on the Isonzo, the Austro-Hungarian military leadership saw the time for a decisive blow against Italy as given. A success of this operation would have neutralized Italy, which at that time could not have counted on allied aid to any significant extent and which alone would not have been able to compensate for these losses, and Austrian troops would have been released for the fight on the western front - like it was originally planned by the allies' strategic concept. Such an approach against Italy could only succeed with German support, which is why the Austro-Hungarian Chief of Staff Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf presented his plans to the German Supreme Army Command in the winter of 1915 and asked for support. The German chief of staff, Erich von Falkenhayn , did not see himself in a position to do this, however, as he was already in the middle of the preparations for the attack on Verdun and believed that he would not be able to release any troops. The animosities between the two chiefs of the general staff led to open resentment and, in the case of Conrad von Hötzendorf, to the view that one then had to go through it alone (which has already met with various rejection at the level of the brigade and division commanders , as the situation here was assessed more realistically ). Only the withdrawal of some strong Austro-Hungarian units from the joint eastern and south-western front and their replacement by troops of the second category or by Bulgarian units could be achieved at the German high command. At the highest command level, however, it was hoped to beat Italy alone.

Planning

In mid-February 1916, the first planning and preparations began. At the headquarters of the Army High Command (AOK) in Teschen , an exchange plan for the detachment of combat troops from the east was drawn up and implemented. Affected by this were the army groups on the Eastern Front, as well as the 5th Army (on the Isonzo) and in Carinthia standing 10th Army . The command of the Southwest Front in Marburg under Colonel General Archduke Eugen was in charge of the overall operation . To lead the main thrust, an 11th Army was rebuilt under the command of the Regional Defense Commander of Tyrol, Colonel General Dankl . The areas from the Ortler to Lake Garda , the Fassa and Pustertal and the Dolomite fronts that were separated from the attack area remained under the command of the National Defense Command, which was led by the former commander of the disbanded XIV Corps, General of the Infantry Roth .

The 3rd Army (Colonel General Kövess ) to be brought up from the Balkans was designated as a reserve , which should , if necessary, push into the attack wedge and expand it. The first wave of attacks consisted of the following associations:

- III. Corps (Commander General of the Infantry Krautwald von Annau ) with the 22nd Landwehr Infantry Division and the 6th and 28th Infantry Division

- InfRgt No. 96 - InfRgt No. 87 - InfRgt No. 47 - LdwInfRgt No. 37 - Feldjäger Baon No. 7 - Feldjäger Baon No. 22 - Feldjäger Baon No. 24 - Feldjäger Baon No. 11 - kk LandesschtzRgt No. I - kk LandesschtzRgt No. II - kk LandesschtzRgt No. III - Bosnian-Herzegovinian InfRgt No. 2 (39 infantry battalions in total )

- VIII. Corps (Commander Feldmarschalleutnant von Scheuchenstuel ) with the 57th and 59th Infantry Divisions

- InfRgt No. 92 - InfRgt No. 93 - InfRgt No. 90 - InfRgt No. 52 - InfRgt No. 48 - Bosnian-Herzegovinian InfRgt No. 1 - Bosnian-Herzegovinian InfRgt No. 3 (in total 20 infantry battalions)

- XX. Corps (Commander Field Marshal Lieutenant Archduke - Heir to the Throne Karl ) with the 3rd and 8th Infantry Troop Divisions

- Kaiserjäger Rgt No. 1 - Kaiserjäger Rgt No. 2 - Kaiserjäger Rgt No. 3 - Kaiserjäger Rgt No. 4 - InfRgt No. 21 - InfRgt No. 7 - InfRgt No. 14 - InfRgt No. 50 - InfRgt No. 59 (total 32 infantry battalions)

- XVII. Corps (Commander General of Infantry Křitek ) with the 18th and 48th Infantry Troop Divisions, as well as the 181st Infantry Brigade (a total of 26 infantry battalions)

(The XVII. Corps did not originally belong to the 1st meeting, but to the 3rd Army and thus one of the following units. The 3rd Army did not intervene until May 20th.) However, the 18th ITD ( Infantry Regiment No. . 73 and Landwehr Infantry Regiment No. 3) already deployed in Valsugana in advance and the 48th ITD involved in the attack operations on the right wing.)

A total of 14 infantry troop divisions and 64 artillery batteries, some of the heaviest caliber, were deployed (with the second meeting). (Due to the constant shifting of individual units, this battle order was weakened within a very short time and after a few days no longer corresponded to the original arrangement.)

The operation was carried out with great precision and in what was believed to be the greatest possible secrecy. However, it was possible to keep the details of the intended attack a secret from the enemy intelligence services until the end, by not letting anything go in the own troops down to the individual command posts, since the infiltration of the military offices with spies of the opposite side was to be assumed certain . The command of the Southwest Front was sworn to the utmost silence, and the troop shifts were declared with a new offensive against Russia. It was not until the end of March that the army commanders learned of the General Staff's intentions, with the War Office being the last to be informed. The heavy and heaviest artillery was transported to the operational areas under the guise of re-arming the Trento fortress and the relocation of the command staff from Marburg to Bolzano was disguised as relocation to Ljubljana .

March

The entry of the transport trains with troops and supplies into the Adige Valley on the already overloaded railway lines took place on adventurous detours for camouflage reasons. The trains from Russian Poland , Galicia , southern Serbia and Montenegro went to Trieste , then up the Isonzo , through Carniola , Styria and Carinthia, and then ran from Spittal an der Drau towards Franzensfeste . Other trains were through Slovakia , and Upper Austria , via Schwarzach-St. Veit, Wörgl and Innsbruck over the Brenner Pass . In Franzensfeste, the southern railway transported the trains rolling in from the eastern and southwestern fronts to Bozen and the unloading stations of Matarello, Calliano and Rovereto in the Adige Valley, as well as to Pergine , Caldonazzo and Levico in the Sugan Valley ( Val Sugana ). Due to the narrow terrain, the troops had to be distributed to the higher valleys until shortly before the attack date.

The march to the staging area took place from the Adige Valley for troops and train via the Serrada plant , via Folgaria and Vattaro to the plateau of Lavarone , while for the units from the Val Sugana only the road to Monte Rover and a path through the Valle Pisciavacca to Were available. All this was done in the hope not to attract the attention of the opponent. To what extent this has been successful remains to be seen; In particular, several Austrian defectors (General Capello mentions at least four in his memoirs Noti di Guerra , published in 1927 , including a master builder who pretended to be an engineer ) brought information about this to the opposing side. After rumors surfaced there, grotesquely enough, a number of Italian soldiers that could not be determined immediately left the Austrians. It was this to be members of the 63rd, 64th, 79th and 80th Infantry - Regiment and the Alpini battalions Val Leogra and Vicenza of the 6th Alpini Regiment.

Italian measures

After the Comando Supremo had recognized the overall situation with the threat behind its Isonzo forces, a study for the case of an Austro-Hungarian major offensive in the spring was drawn up from the north on January 28, 1916. The two leaders of the Italian armies on the South Tyrolean front immediately began to request reinforcements several times from Chief of Staff Cadorna in Udine . However, this refused any kind of troop relocation, as he the measures of the k. u. k. Army High Command only viewed it as a deception. Nonetheless, he ordered the further expansion of the defensive lines and gave permission to straighten the front. Highly exposed positions were given up and withdrawn.

The Italian position system existing in the attack section was regarded by the Italians as almost impenetrable due to the three-fold staggering and its depth. In addition there were the flanking fortifications and groups of works Forte Monte Verena , Forte Campolongo and (the, however, still unfinished) Forte Campomolon in the first line, Forte Monte Enna , Forte Monte Maso and Forte Casa Ratti in the second and third line. Since the middle of March, attempts have been made to disrupt the Austrian preparations for attack through local operations. However, major activities have so far been prevented by the extremely snowy winter. The general plan provided for an offensive operation by the V (IT) Corps in the Adige Valley, whose thrust was aimed via Rovereto and Vattaro at Lake Caldonazzo , while the III (IT) Corps was to fight its way on both sides of Lake Garda, take Riva and advance to Judiciary . These operations, which began on April 7th and 8th, collapsed on the same day. At the same time, preparations for the demolition of the Col di Lana began. When the signs began to intensify from March onwards, the Italian Army Command decided on March 22nd to take comprehensive operational measures. Extensive reinforcements were assigned to the Tyrolean Front and detailed orders for attack were given to the V (it) Corps for the area of Val Sugana. From the beginning of April the 15th (it) Infantry Division began attacking the Austro-Hungarian positions in the area of St. Osvaldo - Monte Broi. To fend off these attacks, the k. u. k. Army Command deployed the 18th Infantry Division belonging to 3rd Army, although this was originally intended to be avoided. Due to the fierceness of the fighting in this sector, General Cadorna felt obliged to visit this sector in person and announced that the main thrust of the Austro-Hungarian attack would probably be expected here.

Groups of the kuk associations

According to the original plans, the staging areas and targets of the 11th Army were distributed as follows:

Right wing:

- VIII. Corps from the staging area Rovereto - Moietto - Monte Finochio with attack direction Vallarsa (Brandtal) on Monte Zugna (1772 m), Col Santo (2112 m), Borcola pass (Passo della Borcola 1207 m) and Passo Pian delle Fugazze. The extended mission of the advance with a pincer movement to the left as far as Thiene was taken into account by an additional division (the 48th ITD of the XVII. Corps).

Center:

- XX. Corps in the center from the Lavarone area (Chiesa - Lusern) with the main direction of attack over the plateau of the Seven Municipalities and through the Val d'Astico to Arsiero and Thiene.

- III. Corps to the left of it from the area Lusern - Passo di Vezzena - Pizzo di Levico with the main attack direction at Monte Kempel and Monte Cima de Portule past through the Val d'Assa towards Asiago .

Left wing:

- XVII. Corps with 18th ITD from Borgo (Valsugana) - Castelnuoveo and Scurelle through the Valsugana southwards towards Passo Grigno and Primolano.

After the Austro-Hungarian leadership had gained new insights into the deployment of the Italian units, it was believed that the least resistance was to be expected in Vallarsa. For this reason the VIII. Corps deployed here was strengthened to 41 battalions of infantry, the XX. Corps ultimately had 32 battalions of infantry. The III. Corps should initially remain in its starting position and only after reaching the Monte Toraro (1817 m) and the Spitz Tonezza (1496 m) through the XX. Corps intervene in addition and from the height of Passo Vezzena roll up the ridge of the Cima Mandriolo (2049 m) with its artillery masses and then advance further south through the Val d 'Assa. Depending on the development of the situation, the 18th ITD of the 3rd Army already deployed in Val Sugana should continue to attack there or be pulled up to the heights.

The Italian defenses

The permanent defensive positions in the attack area had already been set up as a counterpart to the Austro-Hungarian forts in peace and were called Fortezza Agno-Assa during the neutrality phase from August 1914 to May 1915. From May 24, 1915 the system was renamed Sbarramento Agno-Assa and divided into three sectors:

I.Sector Schio : from Forte Monte Maso via Forte Enna, Battery Monte Rione and Battery Aralta to Paso Coletto Grande.

II. Arsiero sector: From Cornolò and Battery San Rocco to the batteries around Monte Toraro and Forte Campomolon.

III. Asiago sector: From Forte Casa Ratti with all positions on the left side of the Astico to Valsugana .

After the strengthening of the facilities continued to be built after the start of the war (naturally only field positions were built) the k. u. k. Evidence bureau for the planned start of the offensive provide evidence of the following barriers:

- Line Monte Civillina - Forte Monte Enna - Monte Rione - Priafora ridge - southern part of the Tonezza plateau - Forte Casa Ratti - Forte Punta Corbin - along the southern edge of the Val d'Assa to Caserma Interrotto and the Tagliata Val d'Assa - northwards to Monte Kempel with the subsequent steep drop into the Valsugana

- Line Passo Pian delle Fugazze - Forte Monte Maso and the Tagliata Bariola

- Line Monte Toraro - Monte Campomolon with the unfinished Forte Campomolon - to the eastern edge of the Tonezza plateau

- Line Forte Campolongo - Forte Monte Verena with associated battery positions Verenetta and Rossapoan

In addition, the heavily fortified Monte Zugna on the ridge between the Vallarsa and the Adige Valley, the Monte Corno (today Monte Corno Battisti) north of the Valle di Foxi, the Col Santo northeast of it, and as the cornerstone of the entire front section of the Corno di Pasubio came as key positions (also called Monte Pasubio). The unfinished Valmorbia tank factory in Vallarsa, which was abandoned by the Austrians when the front was withdrawn in 1915 and occupied by the Italians, must also be mentioned. It was now called Forte Pozzacchio, but had no long-range combat value and was only suitable for infantry close-range defense.

Groups of Italian associations

On May 15, 1916, the attackers faced units of the 1st Italian Army , commanded by Pecori Giraldi . General Pecori Giraldi had only taken over from General Roberto Brusati a week earlier on May 8, 1916 , after the Austro-Hungarian offensive plans had become more than obvious and Brusati had been removed from his office by Chief of Staff Cadorna. Brusati was accused of neglecting the defensive tasks assigned to the 1st Army of Cadorna and of having set up insufficient defensive positions that would not have withstood a decided enemy onslaught.

On May 15, the 1st Army was subordinate to the following units in the attack area:

- 37th Infantry Division, lined up on the far right Austro-Hungarian attack section between the Adige Valley and the orographic left side of the valley of Vallarsa, Monte Zugna, with 22 small and 11 medium-caliber guns. The division was subordinate to the Taro Infantry Brigade (207th and 208th InfRgt) and 3 battalions of Territorial Militia.

- 5th Army Corps under the command of General Gaetano Zoppi lined up from the orographically right side of the valley of Vallarsa to the northern edge of the plateau of the seven municipalities.

Subordinate to the V Army Corps:

- Barrier Agno - Posina in the Pasubio area, under the command of General Pasquale Oro with the Roma Infantry Brigade (79th and 80th InfRgt), the Alpini Battalions Monte Berico and Val Leogra and the 8th and 44th Regiment of the Territorial Militia ( a total of seven battalions);

- 35th Infantry Division on the Folgaria plateau to the orographic left bank of the Val d'Astico under the command of General Felice De Chaurand with the infantry brigades Ancona (69th and 70th InfRgt), Cagliari (63rd and 64th Infantry Division). InfRgt), the Alpini Battalion Vicenza as well as three battalions of territorial militia and three battalions of financial guards ;

- 34th Infantry Division from the right bank of the Val d'Astico to the northern edge of the plateau of the Seven Municipalities under the command of General Alessandro Angeli with the Infantry Brigades Ivrea (161st and 162nd InfRgt), Salerno (89th and 90th Infantry Division) InfRgt) and Lambro (205th and 206th InfRgt), with the Alpini Battalion Monte Adamello and two regiments of Territorial Militia (45th and 46th Reg. With 8 battalions in total).

The Brenta-Cismon barrier operated between the Brenta River and the Torrente Cismon on the left wing of the attack, under the command of General Donato Etna . The infantry brigades Venezia (83rd and 84th InfRgt), Jonio (221st and 223rd InfRgt) and Siena (31st and 32nd InfRgt) were available. He also had the six Alpini battalions Monrosa, Intra, Feltre, Val Cismon, Monte Pavone and Val Brenta as well as three and a half battalions of territorial militia and a battalion of financial guards.

The 9th Infantry Division in the area of Santorso , Schio, Malo under General Maurizio Gonzaga and the 10th Infantry Division between Bassano del Grappa and Primolano and the 5th Field Artillery Regiment were available as army reserves.

On May 20, in view of Austria's initial successes and the increasing risk of a breakthrough, Cadorna had the 5th Army under General Pietro Frugoni deployed . These troops, composed of reserve units and hurriedly drawn from the Isonzo front and from Albania , were positioned in the lowlands between Vicenza and Treviso . This gave the Italians another 5th Army Corps with 10 divisions and around 180,000 men as reserves.

weather condition

The exceptionally snowy winter prevented compliance with the original attack dates, which had to be postponed again and again. Attempts to get over the snow cover soon proved futile due to the onset of foehn weather. The men lined up with full equipment sank down to their hips and only came forward at a snail's pace, an attack against developed positions was completely out of the question. New attempts were made every day, the height of the snow was measured and any change noted, but no change occurred. Until mid-May, depressions of up to four meters in snow were not uncommon.

Start of attack

Due to the unfavorable weather conditions, the attacking troops were doomed to inaction on a large scale. This time was used for extensive enemy reconnaissance. Aircraft recordings, deserters and the bringing in of prisoners by ship patrols allowed a precise assessment of the opposing positions. Signs of Italian preparations for an attack in the Val Sugana caused the commanding General Dankl to set the start of the attack on May 17, 1916. When this date became known to the Army High Command in Teschen, Dankl was informed that the order to attack might have to be brought forward and that the troops would have to be ready four days after receipt of the instruction.

In the meantime, the German General August von Cramon, as the representative of the Supreme German Army Command, had expressed their grave concerns about the planned offensive among the Austrians. Falkenhayn would have preferred if the Austro-Hungarian units had been deployed in France , since in his opinion this offensive had little prospect of success. As expected, Conrad von Hötzendorf rejects this request, as the preparations have already progressed so far that it is no longer possible to cancel.

On May 13, 1916, the attack orders for May 15, 1916 at 6:00 a.m. were given. At this point the barrage began from 369 guns, including 120 of the caliber 24-42 cm. The Italian fortifications Forte Monte Verena, the neighboring Forte Campoluongo and the still unfinished Forte Campomolon (in the latter four 28 cm howitzers were posted in the open position) had already been fought intensely by artillery in June 1915 and were only used for infantry defense the situation. Nevertheless, they were again under the heaviest fire and this time were completely destroyed. As predetermined, the artillery of the III. Corps not in their own attack section, but in that of XX. Corps. The front of the Italian 35th Infantry Division, about six kilometers wide, was affected, and especially the position of the Ancona Brigade. At 9 a.m., the so-called extermination shooting followed and at 10 a.m. the order to attack the infantry. Shortly afterwards, the first Austro-Hungarian troops of the I./III under Captain Oreste Caldini penetrated the Italian trenches on the Malga Pioverna. Although the element of surprise had been wasted, the trenches could be overrun almost anywhere in the first onslaught. After the initial gains in terrain, however, the resistance stiffened, and reserves that were rapidly dwindling made progress more and more difficult. When Italian reaction units were withdrawn from the Isonzo front and relocated to the distressed sections (the Italian leadership had meanwhile recognized that there would be no support from Germany and that the front on the Isonzo could therefore be temporarily thinned out) and the much underestimated stocks Ammunition, which forced the Austrian artillery to reduce shelling on the Italian front, as well as general supply difficulties, the offensive finally came to a standstill on June 15.

Attack successes

Right attack section

The VIII. Corps conquered the ridge with the Zugna Torta (1,257 m), the Monte Zugna (1,864 m), the Coni (1,772 m) and the Cima Mezzana as well as the Vallarsa on its right wing. This wing pushed past Monte Pasubio to the right. The center conquered the Col Santo (2,112 m), the Monte Corno (now called Monte Corno Battisti) and finally got stuck on the Corno di Pasubio (also called Monte Pasubio). The left wing could push past Monte Pasubio on the left and reach the Posina, Monte Priafora and Monte Aralta line. To secure the flanks, units of the Standschützen and the 11th Infantry Brigade advanced downstream via Mori in the Adige Valley .

Middle attack section

The middle section of the attack collided with the XX. and the III. Corps over the plateau of the seven municipalities over the Italian fortifications Forte Monte Verena and Forte Campolongo, already destroyed by the artillery, (on the evening of 16 May the 1st regiment of the Tyrolean Kaiserjäger reached the imperial border near the Pinoverna ridge) conquered the Monte Cimone ( Infantry Regiment No. 14 ) and the small towns of Asiago (Asiago Basin) and Arsiero, however, could only advance within one line to just before the two villages. The fortifications Caserma Interrotto and Forte Casa Ratti could be taken without a fight in this section . In the latter case, a dispute broke out between the 14th sapper battalion and the 50th infantry regiment about who was the first to enter the fort. The AOK then decided in favor of the sappers. On June 1, the Monte Cengio was stormed, the troops and stood on the edge of the Venetian plain, whose access was only blocked by the massif of Monte Paù.

Left attack section

Here the Austro-Hungarian troops met with parts of the III. Corps and the XVII. Corps through the Valsugana and the adjacent heights to the east and south-east, conquering Monte Kempel (2,295 m), Monte Colambaretta di Portule (2,046 m) and the entire mountain ridge up to Monte Meletta, and then in Valsugana about four kilometers from Grigno having to stop.

Suspension of the offensive and withdrawal of the front

Despite all further attempts, it was no longer possible to advance beyond the positions that had already been reached, since the supply of material and food had reached a difficulty that was almost impossible to overcome. The bad weather conditions (wet and cold) did the rest.

Another limited attack attempt on June 16 failed. On June 18, the order to withdraw was issued. The reason for this was the Brusilov offensive started by Russia on June 4th , the catastrophic effects of which on the Austro-Hungarian eastern front could only be absorbed with troops from the South Tyrolean region. From the night of June 24th to June 25th, the front was therefore moved back a strip of about three to four kilometers (line Mattasone - Valmorbia - Pasubio - Borcolapass - Monte Cimone - Casteletto - Roana - Monte Interrotto) to positions that were easier to defend - Cima Dieci - Civaron - Salubio - Setole). Only Monte Pasubio and Monte Cimone were not given up and from then on sat like a thorn in the Italian front. The Italian counter-offensive that began on June 26th and lasted until July 8th did not bring any measurable gains in terrain.

Final consideration

Like many other actions by the Austro-Hungarian armed forces, this one was also shaped by three factors: too little - too indecisive - too weak . As usual, there were tactical and strategic errors at the AOK and the Army Group , quarrels between the two agencies on the one hand and the armies and corps on the other, which ultimately led to the blame on each other after the offensive failed. One of the points of criticism was the five days with which the III. Corps, to whose artillery in support of the XX. To deploy the corps and thus grant the corps commander, Archduke Karl, a brilliant victory. Also that the two armies (11th and 3rd) did not advance one after the other as planned, but the 3rd Army suddenly developed alongside the 11th Army and attacked almost simultaneously. The need for artillery ammunition, the shortage of which contributed to the failure of the offensive, as well as the transport problems of supplies were not given sufficient consideration. Because of the difficult terrain, they got bigger the further south one went. It became almost impossible to supply the soldiers who persevered in the cold and wet with warm or even sufficient food, which led to a disproportionately high loss of food due to stomach and intestinal diseases (on Monte Spini, the transport of the food containers to the foremost trenches takes five to six hours - on top of that the approach routes were under artillery fire). The main cause of the action, which was doomed to failure from the outset, is considered to be the serious mistake of the management to try to carry out the operation against their better judgment without German support. One acted here (not for the first time) literally according to the motto: somehow it will work out . In addition, there was the refusal of the German Supreme Army Command to make troops available for this project, since these troops had been designated for the battle of Verdun, which was given priority.

Strongly weakened by the withdrawal of the troops to repel the Brusilov offensive and due to the adverse circumstances that had arisen in the meantime, further penetration into the Venetian lowlands seemed unrealistic. An advance to Venice without German support would hardly have been possible anyway.

literature

- Maximilian Lauer: Our Rainer in World War 1914/18 . Salzburg 1919.

- Ministero della Guerra - Stato Maggiore Centrale - Ufficio Storico (ed.): Guerra Italo - Austriaca 1915-18. Le medaglie d'oro. Volume secondo - 1916 , Rome 1926.

- Robert Mimra: Battery 4 . Bergland Buchverlag, Graz 1930.

- Austrian Federal Ministry and War Archives (Ed.): Austria-Hungary's Last War 1914–1918. Fourth volume. The war year 1916. First part . Publishing house of the military science reports, Vienna 1933.

- Ministero della Guerra - Comando del Corpo di Stato Maggiore - Ufficio Storico (ed.): L'Esercito Italiano nella Grande Guerra (1915-1918). Volume III - Tomo 2 ° (narrazione), Le operazioni del 1916. Offensiva Austriaca e controffensiva Italiana nel Trentino - Contemporanee operazioni sul resto del fronte (Maggio - Luglio 1916) , Rome 1936.

- Ernst Wißhaupt: The Tyrolean Kaiserjäger in the World War 1914–1918 Volume II. Göth, Vienna 1936.

- Fritz Weber : Alpine War . Artur Kollitsch Verlag, Klagenfurt 1939.

- Fritz Weber: The end of an army . Verlag Franz Eher Successor Munich 1940.

- Anton Graf Bossi-Fedrigotti : Kaiserjäger - Fame and End . Leopold Stocker Verlag , Graz 1977, ISBN 3-7020-0263-4 .

- Adolf Paulus: The 1st World War in the picture . R. Löwit Verlag, Wiesbaden 1979.

- Anton Wagner: The First World War. A look back . Troop service paperback, Carl Ueberreuther, Heidelberg – Vienna 1981.

- Hans Jürgen Pantenius: Conrad von Hötzendorf's idea of attack against Italy. A contribution to coalition warfare in the First World War (Part II), Böhlau, Cologne 1984, ISBN 3-412-03983-7 .

- Helmut Golowitsch: And the enemy comes in to the country ... . Book Service South Tyrol, Nuremberg 1985, ISBN 3-923995-05-9 .

- Hans Magenschab : The grandfathers' war 1914–1918 . Verlag der Österreichische Staatsdruckerei, Vienna 1988, ISBN 3-7046-0115-2 .

- Heinz von Lichem : War in the Alps . Athesia Verlag, Bozen; Weltbild, Augsburg 1992, ISBN 3-89350-545-8 .

- Walther Schaumann : From the Ortler to the Adriatic. Dall'Ortles all'Adriatico. The southwest front in pictures. Immagini del fronte italo-austriaco 1915–1918 . Mayer, Klosterneuburg – Vienna 1993.

- Viktor Schemfil: The Pasubio Fights 1916–1918 . Verlag Buchdienst Südtirol, Nuremberg 1994 (reprint from 1936), ISBN 3-923995-03-2 .

- Erwin A. Grestenberger: K. u. K. Fortifications in Tyrol and Carinthia 1860–1918 . Mittler & Sohn, Vienna 2000, ISBN 3-8132-0747-1 .

- Robert Striffler: The mine war on Monte Cimone . Verlag Buchdienst Südtirol, Nuremberg 2001, ISBN 3-923995-21-0 .

- Rest-Ortner-Ilmig: The emperor's rock in the 1st World War. Uniforms and equipment of the Austro-Hungarian Army from 1914 to 1918 . Verlag Militaria, Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-9501642-0-0 .

- Wachtler-Giacomel-Obwegs: Dolomites . 2 volumes, Athesia Verlag Bozen 2003/2004, ISBN 88-87272-44-1 .

- Robert Striffler: From Fort Maso to Porta Manazzo: History of the construction and war of the Italian forts and batteries 1883-1916 . Book Service South Tyrol, Nuremberg 2004, ISBN 3-923995-24-5 .

- Leonardo Malatesta: Altipiani di fuoco. La strafexpedition austriaca del maggio - giugno 1916 Istrit, Treviso 2009, ISBN 978-88-96032-12-1 .

- Hans Dieter Hübner : On the way in historical footsteps Volume 1. Hikes and excursions on the focal points of the Austro-Hungarian South Tyrol offensive in 1916. Volume 1: Around the Pasubio. Books on demand; Edition: 1 (May 18, 2013), ISBN 978-3-8391-5723-7 .

- Hans Dieter Hübner: On the way in historical footsteps Volume 2: Hikes and excursions on the main focuses of the Austro-Hungarian South Tyrol offensive in 1916. On the plateaus of Folgaria and Fiorentini, in the Laghi Basin and in the Posina Valley, Books on Demand; Edition: 1 (August 13, 2013), ISBN 978-3-7322-1393-1 .

- Gerhard Artl: The "punitive expedition": Austria-Hungary's South Tyrol offensive 1916 . Verlag A. Weger, Brixen 2015, ISBN 978-88-6563-127-0 .

- Compass Carta Touristica Trento-Lévico-Lavarone No. 75

- Compass Carta Touristica Rovereto-Monte Pasubio No. 101

Web links

- Austro-Hungarian World War II Diary (1919), Volume II (1916–1918): The fight against Italy

References & comments

- ^ Anton Wagner: The First World War. A look back . Troop service pocket book, Carl Ueberreuther, Heidelberg – Vienna 1981 p. 153.

- ↑ Leonardo Malatesta: Altipiani di fuoco. La strafexpedition austriaca del maggio - giugno 1916 p. 93.

- ↑ a b Leonardo Malatesta: Altipiani di fuoco. La strafexpedition austriaca del maggio - giugno 1916 p. 184.

- ↑ Viktor Schemfil: The Pasubio Fights , p. 10.

- ↑ Austria-Hungary's last war . Volume IV, p. 198.

- ↑ from 1917: State Rifle Division

- ↑ However, writing of the kuk Militäradministratur to 1918 since the spelling reform of 1996 as Field Marshal Lieutenant referred

- ↑ E. Wisshaupt: The Tyrolean Imperial Hunters in World War 1914-1918 . Volume II, p. 152 ff.

- ↑ Austria-Hungary's Last War, Volume IV, p. 198.

- ↑ Austria-Hungary's Last War, Volume IV, p. 227.

- ↑ LEINGG Volume II Annex 36.

- ↑ Leonardo Malatesta: Altipiani di fuoco. La strafexpedition austriaca del maggio - Giugno 1916 pp. 65–89.

- ↑ Leonardo Malatesta: Altipiani di fuoco. La strafexpedition austriaca del maggio - giugno 1916 pp. 91–93.

- ↑ La battaglia degli altipiani. In: esercito.difesa.it. Retrieved July 26, 2018 (Italian).

- ↑ La “Punitive Expedition” contro l'Italia 15 maggio - 16 giugno 1916. In: ana.it. Retrieved July 26, 2018 (Italian).

- ↑ there was talk of the snowiest winter in living memory

- ↑ Austria-Hungary's Last War, Volume IV, pp. 194 ff.

- ^ Anton Graf Bossi Fedrigotti: Kaiserjäger - Fame and End . Graz 1977, p. 270.

- ↑ Schiarini: L'Armata del Trentino 1915-1919 . Pp. 103-104.

- ↑ Robert Striffler: The mine war on Monte Cimone. Series of publications on contemporary history in Tyrol . Volume II, p. 38.

- ↑ Fritz Weber: The end of an army . Munich 1940, p. 63 ff.

- ^ Anton Graf Bossi-Fedrigotti: Kaiserjäger - Fame and End . Graz 1977, p. 321.

- ↑ Viktor Schemfil: The Pasubio fights series of publications on contemporary history of Tyrol, Volume 4 Nuremberg, no year, p. 26.

- ↑ Robert Striffler: The mine war on Monte Cimone. Series of publications on contemporary history of Tyrol Volume 12, Nuremberg 2001, p. 13.