Sweden in the time of the Kalmar Union

Sweden in the time of the Kalmar Union ( Swedish Sverige under Kalmarunionens tid ) deals with Swedish history between the years 1389 and 1523, when Sweden , Denmark and Norway first united on a political level and then, a few years later, created the Kalmar Union .

In practice, the unification of the Nordic countries was already completed in 1389. However, this act only became official in 1397 when the Kalmar Union was founded. The Union should act as a counterweight to the North German Hanseatic League . A constantly recurring reason for controversy was the struggle for the distribution of power between the center of the Union and the imperial councils in the three countries. The struggle for power between Denmark and Sweden ensured that Scania and Götaland in particular were repeatedly devastated by troops.

Margarethe I.

From 1389, Sweden entered into a personal union and from the summer of 1397 a real union with Denmark and Norway . Through the Recess of Nyköping in 1396, the Imperial Council (a grouping of ecclesiastical and secular rulers) and Princess Margaret I had agreed on the terms and on June 17, 1397 Margaret I's great-nephew, Erik VII , became at the castle Kalmar crowned the Union King . 67 nobles from the three countries were present. At the coronation , Erik VII was only 15 years old. As his guardian Margaret I continued the business of government. Two original documents from the coronation are still preserved today: the Union letter and the coronation letter.

In the Union letter it was made clear that after the death of Erik VII the Union should have only one king who should be elected by all rich people. Each of the empires should be governed according to its own laws. Externally, however, the Union would function as a unit. Should a war break out, each country would help the other. There are different views as to how the Union letter is to be interpreted. Contrary to the custom at the time, the Union letter was written on paper and not on parchment . Some historians argue that the draft of the Union letter was never ratified by all participants , including the history professor Erik Lönroth .

Gotland was ruled by Erik von Mecklenburg . He used the island as a base for his pirates . After Erik von Mecklenburg's sudden death on July 26, 1397, his widow , Sophie von Pommern-Wolgast , was ordered by Sven Sture to take over his business. The activities were directed against both Union and Hanseatic ships. After the Teutonic Order had made peace with Poland-Lithuania , in March 1398 they equipped a fleet consisting of 84 ships and a crew of 4,000 and conquered the island. In November 1403 Margaret I made an attempt to retake Gotland, but failed. In 1408 the Teutonic Order gave up the island in exchange for 9,000 English nobles .

War in Schleswig-Holstein

Margaret I continued her attempt to bind Holstein closer to Denmark after Count Gerhard VI. von Holstein died in 1404. With several clever moves she got control of large parts of Schleswig . In June 1410 the war broke out and Erik VII managed to gather troops from Sweden and Denmark. This went without much military progress for both sides and in the autumn of 1412 Margaret I traveled to Schleswig and succeeded in negotiating an armistice of five years. On October 24, 1412, she received homage from the population of the city of Flensburg . She died of the plague just four days later .

In 1416, Erik VII continued the war with Schleswig. The fight against Holstein was not very successful. In June 1424 the Roman-German King Sigismund ruled against the Count of Holstein that they had lost their rights to Schleswig. From this time on, this should belong to the Danish Empire. To celebrate this decision, Erik VII decided to go on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem . This trip should last 20 months. During his absence, Philippa of England took over the reign.

King Erik VII made several attempts to hinder trade in the Hanseatic League. These measures included the construction of Kronborg Castle at the narrowest point of the Øresund and a multiplication of the previous tariffs . When King Erik VII continued his fight against Holstein in the summer of 1426, several Hanseatic cities agreed on a blockade. Several members of the Swedish aristocracy took part in the clashes and in the winter of 1426 the Swedish Imperial Council promised to send 300 knights and riflemen. In July 1427 there was a sea battle in the Øresund . The battle was won by the Union, and when a merchant fleet of 36 Hansa ships sailed into the Oresund the next day, they were easy prey. When the Hanseatic League attacked Copenhagen again in 1428, the Danish-Swedish fleet in the harbor was destroyed. A new Danish-Swedish fleet was defeated by the Hanseatic League in a sea battle at Dänholm off Rügen the following year . Militarily, however, neither side could make greater progress. In 1429 the Dutch and Prussian Hanseatic cities broke the blockade and after the fall of the Danish city of Flensburg in 1431, peace negotiations began.

Domestic political crisis

Both Margaret I and Erik VII had promised to follow Magnus Eriksson's land law, which stipulated that the castle district should be cherished by "native Swedish men". Sources still preserved today say that both Margaret I and Erik VII entrusted the management to trustworthy people. These included: The Danes Peder Ryning and Lage Röd , the Italian (actually Croatian) Giovanni Franco (" Johann Vale "), the Germans Henrik Styke , Hans Kröpelin and Ida Königsmarck from the Mecklenburg family . These people were loyal to the royal family. Even more so than the church, the aristocracy or the Swedish Imperial Council.

The first internal political crisis of King Erik VII was the riot that began in June 1434 in Bergslagen near Västerås Castle . There were several causes of discontent, but the Swedish aristocracy turned a deaf ear to these reasons. The insurgents were able to take control of several Swedish castles, but the most important ones were and remained in the hands of the king. These included Stockholm Castle and Kalmar Castle . In the autumn of 1435, Erik VII was forced to post only Swedes in most of the castles. He also promised to seek the opinion of the Reichsrat before taking any new decisions. In 1436, Charles VIII and Christer Nilsson were appointed imperial court men in Sweden. In Bergslagen, the unrest continued under the leader Erik Puke , known as the Pukefehde . This could finally be seized and was executed in February 1437 . In Västergötland , Närke , Dalarna and Värmland , too , the peasants had instigated revolts. But these were brutally suppressed. In the spring of 1436 the imperial council met in Strängnäs and it was decided that the farmers were forbidden to carry weapons. This only applied to ting negotiations and markets.

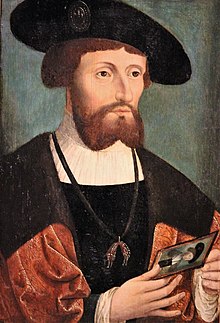

Christoph of Bavaria (Christoph III.)

King Erik VII tried to get Duke Bogislaw of Pomerania to succeed him, but this venture met with opposition from both the Swedish and Danish Councils. In autumn 1438 Karl Knutsson (Bonde) was elected imperial administrator in Sweden, while the Danish imperial council deposed Erik VII on June 23, 1439 and in his place Erik's nephew, Christoph III. , elected to the Danish imperial administrator. On September 29, 1439, the Swedish Imperial Council also declared Erik VII to be deposed.

Christoph von Bayern was elected King of Denmark on April 9, 1440 in Viborg . However, the Swedish Imperial Council made it a condition that the king had to make a government declaration in the form of a royal declaration. This had a great influence on the Reichsrat. On September 13, 1440, Kristofer of Bavaria was elected King of Sweden at Mora Stenar . Karl Knutsson (Bonde) was appointed Drost and received the entire bishopric of Turku , with the exception of Åland as a fief and Öland as a pawn . A few weeks later, King Christopher III changed. his opinion and Karl Knutsson had to be content with Viborg Castle . Christoph's Land Law was ratified on May 2, 1442 . In this it was stipulated that only Swedish citizens could be entrusted with the royal castles and that only Swedes could become members of the Imperial Council.

The deposed King Erik III. had made Visborg Castle on Visby his headquarters. From there he led a fleet of pirates. In the summer of 1446 the Gotland area was conquered by Swedish troops. Negotiations between Christoph III. and the former King Erik VII led to an armistice of 18 months. In 1447 the cousin of Erik VII Bogislaw von Pomerania died and it could be assumed that Erik VII was ready to take over Gotland and thus to inherit the Duchy of Pomerania-Stolp . This was prepared at the end of 1447. King Christoph III. spent Christmas in Helsingborg when he was on his way to the meeting of the Imperial Council in Jönköping . During the holidays he became seriously ill and died on January 5, 1448 at Kärnan Castle .

Christian I. and Karl Knutsson (Bonde)

When the news of the king's death reached the waiting Reichstag in Jönköping, the two brothers Bengt Jönsson Oxenstierna and Nils Jönsson Oxenstierna were appointed imperial administrators. A meeting of the estates was called in Stockholm for the end of May 1448 . On May 23, Karl Knutsson (Bonde) arrived there at the head of a large armed force. The exact circumstances of the next few weeks are largely unknown, but it is clear that the eligible voters elected Karl Knutsson on June 20, 1448 as King of Sweden. On June 28th he was worshiped on the stone of Mora and the following day he was crowned in Uppsala Cathedral.

In Denmark, on September 1, 1448, the 22-year-old Count Christian I was appointed King of Denmark by the Danish Imperial Council. He acted very quickly and offered Erik VII three Danish castles as a fief , including an annual maintenance of 10,000 guilders , in exchange with Visborg's castle. The Danish fleet rushed to Gotland and Erik VII left the command to Olof Axelsson Tott . The Danish troops succeeded in conquering Visby in the summer of 1448 and then forced the Swedish troops to leave the island.

In the middle of summer 1448 Christian I was elected King of Norway by the Norwegian Imperial Council. A minority in the Reichstag would have preferred Karl Knutsson as king. The latter attacked Norway via Värmland and was then crowned King of Norway in Nidaros Cathedral on November 20, 1449. Norway was controlled by the troops I. Christian, including the bailiff on the Akershus Fortress , Hartvig Krummedige . Karl Knutsson's siege of Akerhus was soon abandoned and representatives from both sides met on May 1, 1450 in Halmstad . At the Halmstad meeting it was agreed that when a king dies, the imperial councils of all countries will sit down and, if possible, agree that the last survivor will be the Union king. Karl Knutsson was forced to give up Norway and on July 29th Christian I was crowned King of Norway in Nidaros Cathedral.

King Christian I then began to recruit mercenary troops . In January 1452, King Karl Knutsson had managed to assemble a large army. These gathered at Markaryd to attack Skåne . The Karlschronik reports that there were around 4,000 knights , but this is probably a huge exaggeration. There you will also find information about 20 guns and mobile field artillery. This is the oldest such information in a Swedish war. The Swedish troops moved south and destroyed Helsingborg . They then moved on to Lund . King Karl Knutsson summoned a thing , but the people of Skåne preferred King Christian I. The Swedish attack turned into a plundering campaign . The cities of Lund and Vä were destroyed and Åhus was burned . On February 27th, King Karl Knutsson was back in Sweden.

In the early summer of 1452, King Christian I gathered troops near Halland . The Swedish nobility, who commanded the castles in Västergötland and Småland , only participated with a symbolic contingent. When the troops passed Jönköping , they were inflicted casualties by a peasant army in North Småland. The war ended with a two-year armistice. Several of the Swedish men who had insufficiently participated in the war were sentenced to death by Karl Knutsson. But many of them escaped judgment by fleeing to Denmark.

In 1455 the war started anew, as it Karl Knutsson Marshal Tord Karlsson Bonde succeeded, Dana Borg , south of Värnamo to storm. Karl Knutsson's position weakened, but solely through his own actions. His support among the peasants and the aristocracy waned during the war effort, the import tariffs created dissatisfaction among the citizens in the cities and his plans for expropriations aroused unrest in the church. The Archbishop Jöns Bengtsson Oxenstierna put himself at the head of the rebellion. After a battle near Strängnäs , Karl Knutsson fled to Stockholm. On the night of September 24, 1457 he left Sweden and fled to Danzig . A few weeks later, the archbishop and Erik Axelsson Tott were elected imperial administrators. On June 23rd Christian I was elected king in Stockholm by an electoral assembly and on July 2nd he received homage on the stone of Mora Stenar. The following day he was crowned in Uppsala Cathedral.

The imperial councils of all three countries met in January 1459 in Skara . There King Christian I was promised by the Norwegian and Danish Imperial Councils that his son John I would succeed the throne. This decision was confirmed by the Swedish Imperial Council at a meeting in Uppsala. This was confirmed again at a formal ceremony in Stockholm.

The Schleswig question remained topical, however. In 1448 Christian I had promised Denmark and Schleswig that they would never be united under the same ruler. When in December 1459 Count Adolf III. died childless, Christian I was appointed Count of Holstein and Duke in Schleswig. With that he had achieved what King Erik VII had tried with great effort, but which he never succeeded. The price for this, however, was astronomical. A total of 123,000 guilders, which corresponded to about 30,700 marks or six tons of silver, were to be paid by the entire Union. All farmers and rural residents were asked to pay one mark according to the value at that time.

The high level of taxes in Sweden created resistance. In 1463 a special tax was introduced. Every taxable farmer (Skattebonde) should pay 12 and every other rural dweller six ore. As the farmers in Uppland protested violently, Archbishop Jöns Bengtsson declared that the tax must be abolished. When Christian I returned to Stockholm, he imprisoned the archbishop and sent him to Denmark. The farmers from Uppland now moved to Stockholm and set up camp near Norrmalm . Under the direction of Marshal Ture Tureson , the farmers were attacked by experienced troops and the battle of Helgeandsholmen broke out .

King Christian then received the subsequent approval of the Imperial Council for the archbishop's arrest. In January 1464, the Bishop of Linköping Kettil Karlsson (Vasa) initiated a riot. In February the bishop was made captain and the insurgents marched on Stockholm and began a siege . The troops of King Christian I marched quickly to Småland, Östergötland and Sörmland and came to Stockholm on March 25th. In the meantime the insurgents had withdrawn to Västerås , in the battle at Haraker's Church . There the king's cavalry defeated the lightly armed peasants. The Sturechronik reports on the fighting in the following words:

" Dalakarla ropadhe slaa och skiuth / saa motte han fly aff skoghen wth / och sadhe 'Mik tykker dala är her för stark "

( German The guys from Dalarna called, hit and shoot / so they had to flee into the vast forest / and said: I think Dala is too strong here ). "

King Christian I was forced to turn back to Stockholm, which was still under siege. During the riot, Karl Knutsson was asked to return from Danzig. This followed the request on August 9th and returned with a fleet and recruited mercenaries. The citizens of Stockholm elected him king, but he soon found out that he lacked the support of the aristocracy and that of the Oxenstierna family . A dispute quickly broke out between Karl Knutsson's troops and those of the archbishop. Thanks to Karl Knutsson on January 30th.

In the following year two groups fought for power, on the one hand the Oxenstierna and the Tott . It was the latter group who asked Karl Knutsson on September 21, 1467 to come back and become King of Sweden. At the end of 1468 a dispute broke out again between Swedish and Danish troops in Småland and Västergötland. In the summer, Axevalla Castle , held by Danes, fell and was razed to the ground. Thereafter there were negotiations in Lübeck , in which the representative of Karl Knutssons claimed Schonen, Blekinge , Halland and Gotland.

In the autumn of 1469 there was another riot in Sweden. This was led by Erik Karlsson (Valla) . The riot was mainly directed against Kral Knutsson and the influential sons of the Tott family. This was successful at the beginning, but was knocked down by Sten Sture the Elder and Hans Åkesson (Tott) . Sten Sture also succeeded in inflicting a defeat on Christian I's troops at Öresten . The fighting calmed down more and more in the spring of 1470 and on May 15th Karl Knutsson died in Stockholm Castle .

Sten Sture the elder

On his deathbed Karl Knutsson left his castle to the son of his half-sister, Sten Sture, who was appointed Reich Administrator by the Reichsrat. The disputes between Christian I and his opponents in Sweden were resolved on April 9, 1471 by an agreement. It was agreed that they would meet again in the middle of the summer to clarify questions about the future of the Union.

On July 18, 1471, King Christian I and his fleet unexpectedly came to Stockholm and another Danish-Swedish war began. During this time Sten Sture traveled through Svealand to gather supporters for his fight against Christian I. But Christian I also gathered supporters and was celebrated by the peasantry in Uppland as the Swedish king. Both sides assembled a peasant army and moved to Stockholm under arms. On October 10, 1471, the warring troops met and the battle at Brunkeberg broke out . In the end, Christian I was forced to retreat to his ships and raise anchor.

For the winner Sten Sture and for his main supporters from the Tott family, this also meant that the inhabitants of several countries came into their hands. The lords of the castle Erik Karlsson (Vasa) , Ture Turesson and Magnus Gren lost their fiefdoms , but kept their seats in the Imperial Council.

In the summer of 1472, Swedish and Danish delegations met in Kalmar . On July 2nd, an agreement was signed with the aim of normalizing relations between the two countries. The confiscated goods were to be returned, including those of the Tott brothers, who had supported Sten Sture in his fight against Christian I. The agreement also included freedom of movement across national borders, that outlaws could no longer hide in other countries and also, albeit vaguely, that they wanted to help each other in the event of war.

During new negotiations in the summer of 1476, the Swedish delegation raised the question of whether Christian I should remain King of Sweden. At a meeting of the imperial councils in Strängnäs in the summer of 1477, however, this was rejected.

The question of the future of the Union became topical again when Christian I died in the spring of 1481 and his son Johann I (Hans) , who was appointed heir to the throne in 1459 by the Swedish Imperial Council and the citizens of the larger cities, now came on the power should come. In new negotiations between Denmark, Sweden and Norway in Halmstad in the summer of 1482, John I was elected king over Denmark and Norway. At a meeting in Kalmar on September 7, 1483, the Recess of Kalmar , John I was also appointed King of Sweden. This should come into effect a year later. For this purpose, John I should go to Kalmar, where he should be made king. The reason why King John I did not appear in Kalmar is unknown. However, it may be that the conditions that were imposed seemed too harsh to him and that he felt that he was being repressed by the Imperial Council. The Swedish Imperial Council met the following year in Kalmar, confirmed the union and that all three countries should have a common king.

In the 1480s there were peasant revolts in Västergötaland for several years. The peasants refused to pay taxes, sent despatches and planned a siege of Öresten's castle. The causes and the further course of the uprising are unknown, but the judge Västergötlands Lindorm Björnsson (Vinge) sentenced six people to death.

In 1463, John I signed a trade agreement with the Russian Tsar Ivan III. Trade with Denmark should be increased to the detriment of the Hanseatic League. Sweden was also included in the agreement because John I promised to let the Russian-Swedish border run according to the Treaty of Nöteborg . In the autumn of 1495, Russian troops began to lay siege to the Swedish fortress of Vyborg . The lord of the Vyborg castle, Knut Posse , ordered every fifth Finnish peasant to take up arms. In Stockholm, Sten Sture began gathering troops around him, but they didn't leave Sweden until late autumn. Sten Sture came to Åland on November 30, 1463 . On the same day, the Russian troops began their attack. Probably one of the oldest reports of this battle speaks of the bang in Vyborg . Knut Posse let the Russian troops conquer a tower of his fortress. When the tower was filled with enemies, he blew it up. Thereupon the attack failed and the Russians ended the siege. Sten Sture appointed Svante Sture as the new lord of the castle, and the latter had his troops shipped across the Gulf of Finland to Ingermanland . There he stormed the city of Ivangorod and looted it completely. On March 3, Russia and Sweden signed a new six-year armistice.

The opposition to Sten Sture increased. The critics said that he had not done enough to strengthen the defense on the eastern border. Svante Nilsson moved to the opposition camp when he learned that Sten Sture wanted to take him back for the costs incurred in the looting campaign in Ingermanland. The leader of the counter-movement was Archbishop Jakob Ulfsson . He had a different view of the freedoms of the church than Sten Sture. Sten Sture now tried to get support from the farmers north of the Mälaren . In June he had the archbishop's estate taken by German mercenaries and besieged his Almarestäket castle . The archbishop responded by excommunicating Sten Sture .

King John I gathered troops and this enabled him to besiege Stockholm's castle . Johann I had also built a navy that Sweden had previously lacked. A peasant army that Sten Sture had supported was defeated by Saxon mercenary troops on September 26th at the Battle of Rotebro . It was now important to both parties to resolve the dispute through negotiation. On October 6th, an agreement was reached between John I, Sten Sture and the Imperial Council, which recognized John I as King of Sweden under the terms of the Kalmar recession. Sten Sture was immobilized with several fiefs. On November 25th, John I was formally elected king in Stockholm and not, as was customary, in Mora Stenar. The Imperial Council also determined that Johann I's eldest son, Christian II , should be his deputy. This was formally confirmed in a royal agreement in May 1499.

The king was also given the right to appoint foreigners as bailiffs in certain cases . Many of them treated the farmers badly, which in turn led to criticism of the king. In 1501, the opposition ensured that the Imperial Council was informed of the agreement between John I and Russia from 1493. The Reichsrat calmed the dispute by withdrawing Johann I's right to appoint foreigners as bailiffs. The king wanted to refuse this, but the Imperial Council had created a fait accompli.

On August 1, 1501, seven members of the Imperial Council declared that the king had broken the promises he had made at the Recess of Kalmar and that they were now entitled to revolt against the king. The insurgents were able to take control of the most important castles with the exception of Kalmar and Borgholm . On April 9, Christina von Sachsen was forced to take over the castle from the rebels. Three days later, on April 12th, the Danish fleet landed in Stockholm, but it was already too late. In November 1501 Sten Sture was again proclaimed imperial administrator.

The Swedes now attacked North Halland and Blekinge, and in March 1503 they began a siege of Kalmar Castle. Christina von Sachsen was now a prisoner of war, but in late autumn 1503 she was handed over to Danish representatives in a ceremony. Sten Sture himself chaired this ceremony. On the way back to Jönköping, Sten Sture suddenly fell ill and died on December 14, 1503. Sten Sture's closest confidante, Hemming Gadh , kept the news of Sten Sture's death secret and secretly transferred his body to Stockholm, where he kept it in the Sankt Nikolai Church hid. When the imperial council met again in mid-January 1504, Svante Sture was elected imperial administrator without opposition.

Svante (Nilsson) Stubborn

Svante Sture based his power partly on the peasantry and the mine owners and partly on the merchants of Stockholm. King John I was never formally deposed as king and still had power over Kalmar Castle. Further negotiations between Denmark and Sweden came to the conclusion that the castle should be taken over by the noble Nils Gädda . A one-year truce was decided and they met again in Kalmar in the middle of the summer of 1505.

A year later, Johann I returned with a fleet of 60 ships and a crew of 3,200. Members of the Danish and Norwegian Imperial Councils also came to Kalmar. When it became clear that Svante Nilsson had not sent any representatives, John I put together a court of 24 Danish and Norwegian councilors who accused Svante Nilsson and the seven Swedish councilors of treason. They were sentenced to death and their property was confiscated . The sentence was later by the German-Roman Emperor Maximilian I confirmed. The court also sentenced citizens of Kalmar to death for helping out when the city was conquered by the Swedes in 1502. This later went down in history as the Kalmar Bloodbath .

King John I gave Svante Nilsson a choice between two options. Either he recognized John I as king and his son Christian II as heir to the throne, or he should pay an annual tribute in order to recognize the sovereignty of John I. Svante Nilsson could not accept either of the alternatives. The Danish fleet in the Baltic Sea maintained its blockade and made forays ashore. The cities of Borgå , Åbo and Öregrund , among others , fell victim to the flames. Kastelholm in Åland was conquered by Søren Norby . In retaliation, the Swedes launched a raid against Halland and Skåne. The siege of Kalmar Castle began under the direction of Hemming Gadh.

Although Kalmar Castle was besieged for several years, there was no significant progress to record. The trade blockade against Sweden became more and more onerous and in the summer of 1509 the parties met in Copenhagen and concluded a peace agreement on the condition that Sweden had to pay an annual tribute of 13,000 marks. The peace agreement immediately led to internal tensions in the Swedish Imperial Council. Svante Nilsson, Hemming Gadh and some councilors wanted to continue the fight, but others, especially the bishops, were in favor of keeping peace. Sweden united with Lübeck to form an alliance against Denmark. With the help of warships from Lübeck, Denmark prevented supplies from being sent to Kalmar and Borgholm Castle. Kalmar Castle fell in August 1510 and Borgholm Castle was captured in November.

With the help of Scottish mercenaries, Danish troops led by heir Christian II attacked Västergötland in January 1511. The Danish attackers looted, among other things, the cathedral of Skara and demanded oaths of loyalty. Following this, the Danish armed forces moved from Västergötaland to Finnveden and from there to the south. Svante Nilsson has been severely criticized for his failures in defense. The opposition demanded his resignation. The latter refused to do so until a meeting of the estates also called for resignation. For this reason, the Imperial Council convened a new assembly of estates in Arboga in January 1512.

Sten Sture the younger

At the beginning of the new year, Svante Nilsson died of a stroke , and the Reichsrat elected the judge of Uppland, Erik Trolle, as the new administrator. Svante Nilsson's 19-year-old son, Sten Svantesson , quickly took control of his father's castles and managed to postpone the Reichstag resolution until peace negotiations with Denmark were concluded. During this time he traveled through the country and had himself confirmed as imperial administrator by various farmers' assemblies, just as others had done before him. During this time he also changed his name to Sten Sture (the Younger) as a reference to Sten Sture the Elder, but to whom he was not related. On July 23, 1512, Sten Sture the Younger was elected imperial administrator by the self-government party. She was supported by the prelates, who were terrified by Christian II's rule in Norway.

The 80-year-old Archbishop Jakob Ulvsson resigned in 1514. He proposed Erik Trolle's 26-year-old son Gustav Trolle as his successor . Gustav Trolle was in Rome at the time and Pope Leo X granted him many perks. Among other things, his protection for the Archbishop's castle Almarestäket and the surrounding lands. In addition, Gustav Trolle was given the right to impose an interdict on whoever denied this right, and to maintain a force of 400 men, including absolution for anything this force could do.

When Gustav Trolle made his way from Rome to Sweden, he learned that Sten Sture was staying in the area of Almarestäket Castle. Gustav Trolle claimed the area because it had been left to the archbishop for eternity, while Sten Sture was of the opinion that the land belonged to him and that he could pass it on as a fief. Sten Sture suspected the archbishop of having participated in a conspiracy in 1516. In the autumn of 1516, the lord of the castle was captured at Nyköpings Castle Sten Kristiernsson (Oxenstierna) together with Vogt Bengt Laurensson and the judges Erik Trolle , Nils Bosson (Grip) and Peder Turesson (Bielke) .

At the same time, Sten Sture began a siege of Almarestäket Castle. He was of the opinion that Gustav Trolle had neither taken an oath as Reichsverweser nor an oath as Reichsrat that he had given the oath of allegiance to another and meant Christian II and that Gustav Trolle was a traitor. In fact, Trolle had asked Christian II for help and put Sten Sture under its spell. In the summer of 1517 a Danish fleet landed outside Stockholm, but it was defeated in the Battle of Vädla . At a meeting of the estates in Arboga in early 1517, Sten Sture was given the mandate to continue to besiege Almarestäket Castle. When an imperial assembly was held in Stockholm, Gustav Trolle was accused of high treason and the assembly decided to demolish Almarestäket Castle . The archbishop was forced to surrender and was imprisoned at Västerås Castle. Shortly afterwards came the indulgence dealer and papal legate Arcimboldi , whom the followers of Sture wanted to win over to crown him king. Arcimboldi confirmed the abdication of Trolles against the transfer of the archbishopric. He handed over the archdiocese's estates to the state. The Catholic Church was thus discredited.

Christian II

King Johann I died in 1513. As already mentioned, his son Christian II had been appointed as his successor in 1499. From 1507 to 1513 Christian II was governor in Norway. There he led a tough policy against people who stood up for the freedoms of the church or who did not represent the interests of Norway. There he had found a mistress, Dyveke Sigbritsdatter . She and her mother followed Christian II to Copenhagen, and her mother in particular gained great political influence there. In 1515 Christian II married the 14-year-old Isabella of Austria , a granddaughter of the German-Roman emperor Maximilian I. In the summer of 1518 a fleet of 80 Danish ships, manned by several thousand soldiers, anchored outside Stockholm. The Danes set up camp near Södermalm . On July 27th, the armed forces met there in the Battle of Brännkyrka . The result was a victory for the Swedes, but the war was not yet decided. In the fall, a personal meeting between Christian II and Sten Sture was prepared in Österhanninge . The Danes handed over six hostages to guarantee the safety of Christian II. These included Hemming Gadh , Olof Ryning , Jöran Siggesson (Sparre) , Lars Siggesson (Sparre) , Bengt Nilsson (Färla) and Gustav Eriksson (Vasa) . Instead of meeting, they were forced to board a ship and the Danish fleet returned to Copenhagen.

Christian II began to prepare a campaign against Sweden. Gustav Trolle managed to get a bull of excommunication against Sten Sture, the Archbishop of Lund and the Bishop of Roskilde . This was to be equated with an interdict which forbade holding church services in Sweden. The campaign against Sweden was thus also a Christian duty. In January 1520 Karl Knutsson (Tre Rosor) took over the leadership of the Danish troops in Västergötaland and they were able to rebuild the fortress Älvsborg . The Borgholm Castle was taken and a short time later the city of Kalmar was under Danish control. Sten Sture moved to Västergötaland himself to take part in the defense. The Danes quickly retreated north across the Ätran valley . On January 19, Sten Sture tried to stop the attack at the northern end of Åsunden near Ulricehamn .

The Swedish troops consisted mainly of locally recruited fighters, while the Danish forces were experienced mercenaries. The end was that the Swedes were defeated in the battle of Bogesund (battle on the ice of Åsundes). A bullet from a light cannon struck Sten Sture's leg and severed it below the knee. The Danish armed forces continued to move north, arriving in Arborga on February 7th and Västerås a few days later . At this point Sten Sture had already died a little outside of Strängnäs.

Sten's widow Christina Gyllenstierna ruled Stockholm Castle and wanted to continue the fight. But many imperial councils pleaded for peace to be made, especially against the background that the Danish mercenaries were in the Mälar valley. On March 6th, representatives of the Danes and the Swedish Imperial Council met and agreed that Christian II should be proclaimed King of Sweden. However, only under the conditions that there is a general amnesty and that the Imperial Council receives the influence that was agreed in the Kalmar Recess. But the stubborn faction was still very influential and raised a peasant army from Västmanland and Dalarna. In the Easter period they met the Danish troops outside Uppsala and the Long Battle took place on Friday . The mercenary troops succeeded in driving the peasants to flight. The Danish troops came to Stockholm and began to besiege Stockholm Castle. During the summer several castles fell into the hands of the Danes and in September the Stockholm Palace was taken over after Christian II had promised an amnesty for Christina Gyllenstierna and her supporters. The amnesty also applied to those who were involved in the dispute with Gustav Trolle and the question about Almarestäket. For this Christian II could. Move on September 7 in Stockholm on 4 November, he was in the St. Nicholas Church for Erbkönig crowned. This was followed by the Stockholm bloodbath.

literature

- Dick Harrison: Uppror och allianser. Politiskt våld i 1400-talets svenska bondesamhallen . Ed .: Historiska institutions. Lund 1997, ISBN 91-85057-37-1 (Swedish).

- Dick Harrison: Sveriges historia medeltiden . Ed .: Liber. Stockholm 2002, ISBN 91-47-05115-9 (Swedish).

- Lars-Olof Larsson (historian): Kalmarunionens tid . Ed .: Prisma. Stockholm 1997, ISBN 91-518-4217-3 (Swedish).

- Poul Georg Lindhardt: Church history of Scandinavia . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1983, ISBN 3-525-55390-0 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 72-87.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 84-87.

- ↑ Erik Lönnroth: Sverige och Kalmarunionen 1397-1457 . Akademiförlaget, Göteborg 1969, ISBN 9968-06-108-5 , p. 45 (Swedish).

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 91-94.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 97-99.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 166-170.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 170-174.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 159-165.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 190-243.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 244-249.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 250-258.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 261-262.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 265-270.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, p. 270.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 270-271.

- ↑ Harrison: Uppror och allianser. Politiskt våld i 1400-talets svenska bondesamhallen. P. 329.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 272-277.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 277-280.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 280-281.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 284-287.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, p. 288.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 289-290.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 292-294.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 295-298.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 298-303.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 306-315.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 315-316.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 320-321.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 321-325.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, p. 329.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 335-336.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 338-339.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 343-346.

- ↑ Harrison: Uppror och allianser. Politiskt våld i 1400-talets svenska bondesamhallen. Pp. 60-61.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 358-362, p. 378.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 376-378.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 378-383.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 382-386.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 389-390.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 397-398.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 399-400.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 400-401.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 401-402.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, p. 414.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 414-415.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 416-417.

- ^ A b c Lindhardt: Church history of Scandinavia. P. 26.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, p. 422.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 423-424.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 424-426.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 426-431.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 432-434.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 434-436.

- ^ Larsson: Kalmarunionens tid. 1997, pp. 437-439.