Christina (Sweden)

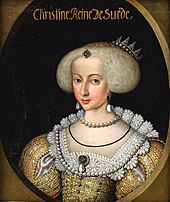

Christina of Sweden (actually Kristina , after her conversion to Catholicism Maria Alexandra ) (* 7 December July / 17 December 1626 greg. In Stockholm ; † 19 April 1689 in Rome ), second daughter of the Swedish King Gustav II Adolf (1594–1632) and his wife Maria Eleonora von Brandenburg (1599–1655), was Queen of Sweden from 1632 to 1654 .

Life

Male upbringing

Christina was five years old when her father died in the Battle of Lützen in 1632 . She came to power under the tutelage of her mother Maria Eleonora and lived with her mother until 1636. At the father's request, she was trained like a crown prince and, from 1635, prepared for the office of king. She learned to ride and hunt, cared little for her looks and spent the nights studying. Because the mother was considered depressed and irresponsible, the Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna took over the guardianship from 1636 and Christina then lived with her aunt Katharina Wasa and her husband Johann Kasimir von Pfalz-Zweibrücken . She apparently had a brief love affair with their son Karl Gustav , who later became her successor on the Swedish throne under the name Karl X.

In 1644 Christina took over the government at the age of eighteen - and from now on of age; the coronation was postponed because of the Torstensson War. Until then, Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna (1583–1654) had reigned. Christina used the support of Johann Kasimir von Pfalz-Zweibrücken and his two sons Karl Gustav and Adolf Johann, with whom she had grown up, to free herself from the tutelage of Oxenstierna. In 1647 she appointed Karl Gustav generalissimo of the Swedish troops in Germany and at the same time signaled her intention to marry him.

During their reign, Jämtland was won, but Königsberg was unsuccessfully occupied. Johan Axelsson Oxenstierna and Johan Adler Salvius acquired Western Pomerania , Rügen and Bremen-Verden for Sweden in the Treaty of Osnabrück in 1648 . Their intervention accelerated the Peace of Westphalia and thus the end of the Thirty Years War .

Pageantry, art and science

During her reign she ran a sumptuous court, one of the most lavish in Europe. Although this made a strong impression on their contemporaries and thus increased their reputation, it also placed heavy financial burdens on Sweden. In order to remedy the situation, she sent the financial specialist Johan Palmstruch to Sweden. In October 1649 she sent René Descartes from Holland, with whom she had corresponded from 1647. From December 1649 she received him, who preferred to be in bed until noon, at 5 a.m. for talks. Descartes died on February 11, 1650 in the house of the French ambassador Pierre Chanut .

Christina bought and built libraries and had a collection of coins and paintings. Her art collection was not just created using conventional methods. In 1648, she ordered or approved the Prague art theft and captured a. a. large parts of the art collection of Emperor Rudolf II , including over 760 paintings, 270 statues, 30,000 coins, 300 scientific instruments and 600 crystals . One of her favorite projects was the University of Uppsala , which she generously equipped with buildings and books such as the Codex Gigas and De laudibus sanctae crucis , including the looted art of Hans Christoph von Königsmarck from the Thirty Years War (from the library of the University of Würzburg or the Lyceum Hosianum in Braunsberg). She supported scholars who dealt with religion, church fathers or ancient languages. For example, Johannes Freinsheim , Cornelius Tollius , Nikolaes Heinsius the Elder , Claude Saumaise , Pierre Daniel Huet , Gabriel Naudé and Samuel Bochart frequented Sweden's court during their time.

Christina was very fond of the theater . The influence of foreign artists on Swedish theater culture gained some significance during her reign. A French ballet group under the direction of Antoine de Beaulieu was hired for Christina's court from 1638. In 1647 the violin player Pierre Verdier came to Stockholm. An ensemble of Italian musicians at Christina's court until 1654 included the composer and guitarist Angelo Michele Bartolotti . In 1652 Vincenzo Albrici was invited to perform at the Bollhuset with an Italian opera group and in 1653 Ariana Nozeman with a Dutch theater group . The French singer Anne Chabanceau de La Barre was appointed by her court singer (Hovsångerska) . She continued to maintain the Royal Court Orchestra (Kungliga Hovkapellet) , which had been in different sizes since King Gustav Wasa . The poet Georg Stiernhielm wrote the play Den fångne Cupido eller Laviancu de Diane for her , in which she herself appeared as the goddess Diana . Also Joost van den Vondel wrote poems for and about them.

Abdication and conversion to Catholicism

Their abdication is preceded by a long history. As early as 1650 there was unrest in parliament. In 1651 the Queen declared that she needed peace and quiet and that the country needed a strong leader. As early as 1651, shortly after her official coronation on October 20, 1650, Christina had declared her intention, but was persuaded by Oxenstierna to refrain from doing so. Another reason for this was that she was supposed to marry her cousin , Elector Friedrich Wilhelm von Brandenburg , but on principle refused to marry.

In May 1652 the Jesuit general Goswin Nickel and Fabio Chigi , who later became Pope Alexander VII, were informed that Christina wanted to convert to Catholicism. Since then, some Jesuits like Gottfried Franken , who taught Christina mathematics, had worked towards a conversion. Christina has now accepted to continue her reign on the condition that she will never be asked to marry again. She lost much of her popularity within a few weeks when Arnold Johan Messenius , who accused her of serious misconduct and called her a Jezebel , was executed .

Instead of ruling, she spent most of her time with her foreign friends in the ballroom (on Sunday evenings) and in the theater. She was encouraged in this by the doctor Pierre Bourdelot , whom she had invited to Stockholm and who recommended that she work and read less and live more for pleasure. Her mother and Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie didn't have much faith in Bourdelot and tried to counteract it. De la Gardie was then sidelined and her mother banished to Gripsholm Castle . In 1653 Christina founded the military order of Amaranten , of which she appointed Antonio Pimentel de Prado to be its first knight . All members had to promise not to (re) marry. However, Christina received increasing public criticism for her lavish policies. Within ten years she had appointed seventeen new counts, 46 barons and 428 members of the lower nobility, and in order to provide them with sufficient allowances, she had sold or mortgaged crown property. In February 1654, she informed the Imperial Council and the Swedish State Council for the second time about her intention to resign and abdicate. Oxenstierna replied that she would regret her decision within a few months. Their proposals were discussed in May. She had asked for 200,000 riksdalers a year, instead she was offered Swedish imperial loans. It was financially secured by income from Norrköping , the islands of Gotland , Öland and Ösel , goods in Swedish Mecklenburg and Swedish Pomerania . Their debts were taken over by the state treasury.

At the Reichstag in Uppsala Castle on June 16, 1654, the abdication certificate was read out and her successor was determined. She left the Swedish crown to her cousin Karl Gustav von Zweibrücken-Kleeburg, the new King Karl X. Gustav (1654–1660).

Shortly afterwards, because of the Northern War , she fled to Antwerp via Münster and Utrecht under the cover name Graf von Dohna . Christina had already packed valuable books, paintings, statues and tapestries from her Tre Kronor castle and sent them on some ships. In Antwerp she was visited by Hannibal Sehested , Leopold Wilhelm of Austria , who invited her to Brussels, and the jealous and insulted Louis II. De Bourbon, prince de Condé . On December 24, 1654 , she converted , initially for political reasons under secrecy, in Brussels in front of witnesses and friends, including Antonio Pimentel and Raimondo Montecuccoli . After nine months she traveled to Innsbruck , where on November 3, 1655, she publicly converted to Catholicism in the Innsbruck Court Church . She was looked after by the papal envoy Lukas Holste . The event was celebrated with great effort. In the evening, the opera Argia by Antonio Cesti was performed in her honor . Her host Ferdinand Karl (Austria-Tyrol) , however, seemed to have been happy when she left.

Much has been discussed about the reasons for the conversion. It is assumed that her conversion was to be seen as a protest against the strict Protestant upbringing, or that she was fascinated by the cultural flowering of Catholic countries in the baroque era, or even that the stubborn ex-queen herself as a Catholic in Italy, which she loved its warm climate would be able to move more freely. The conversion was a triumph for the forces of the Counter-Reformation in Europe, after all she was the daughter of Gustav Adolf, the Protestant hero in the Thirty Years' War.

Rome

From December 1655 she took up residence in the Palazzo Farnese in Rome. Stefano Gradi celebrated her arrival with a welcome speech in Latin. After her confirmation by Pope Alexander VII , she took the name Maria Alexandra , but signed her correspondence with the name "Christina Alexandra". She negotiated unsuccessfully about the crown of Naples with the Spanish, then secretly with Cardinal Mazarin ; but he wanted the crown for France after Christina's death. The details were laid down on a trip to France by Christina in 1656. The plan was betrayed, however, and Christina had the presumed traitor from her entourage, the head stable master Margrave Giovanni Monaldeschi , killed in Fontainebleau Castle on November 10, 1657. The circumstances of the act - she no longer had any royal rights - so outraged the French that she had to leave the country as a persona non grata and was ostracized by society in Rome for a long time. In July 1659 (or 1663?) She moved to Trastevere in the Palazzo Riario, on top of the Janiculus . Carlo Ambrogio Lonati was their concertmaster there, Lelio Colista lutenist, Loreto Vittori was one of their singers.

Christina traveled to Sweden two more times: in 1660, when the abdication was renegotiated after the death of Karl X. Gustav, and in 1667, when she was banned from onward travel and (until the coronation of a new king) from future entry because she was accompanied by a Catholic priest. From 1666 to 1668 she was in Hamburg to take care of the administration of her Swedish property with Abraham Senior Teixeira and his son. She had not given up her political ambitions completely, not least for financial reasons, so she speculated on the crown of Poland in 1668 .

She devoted herself entirely to art and opened the Teatro Tor di nona on January 8, 1671 , the city's first public theater, where, contrary to what was customary at the time, women also played or sang. The whole of Rome was enthusiastic about this innovation, but as early as 1676 this theater was opened on the instructions of the new Pope Innocent XI. closed. Christina was a lover of baroque music and probably played the violin herself. She commissioned compositions from Alessandro Stradella and Bernardo Pasquini . Giacomo Carissimi and Alessandro Scarlatti (1680–1683) became their Kapellmeister. Arcangelo Corelli dedicated his Opus 1 to her and played in Rome in 1685 on the occasion of the coronation of Jacob II (England) .

With the formalities of her new denomination, however, she did not take it too seriously - she was not a “prayer sister”, she said in response to reproaches that she rarely went to confession. She had good contacts with Miguel de Molinos , a Spanish mystic who did not value the sacraments and who was sentenced to perpetual imprisonment in 1687. Christina campaigned for religious tolerance , condemned the persecution of Protestants under Louis XIV . and in 1686 took the Jews in Rome under their personal protection.

She died in Rome on April 19, 1689 and was buried in the Vatican Grottoes in St. Peter's Basilica . Its Latin title on the Epitaph of Carlo Fontana is: CHRISTINA ALEXANDRA D (EI) G (Ratia) SÜC (ORUM) GOTH (ORUM) Vandalorum REGINA (German: Christina Alexandra, the grace of God Queen of Sweden, the Goths and Vandals ).

She appointed her confidante, Cardinal Decio Azzolini , as heir and administrator of the estate, who died seven weeks after her. The Pope later acquired parts of the precious library as well as its letters and documents. Most of them were sold scattered across Europe to cover their debts.

Pallas of the North

After her death, the Accademia dell'Arcadia , which she proposed , was formally founded. Christina was often referred to as “ Pallas ” or “ Semiramis of the North”. But there were also many other stories and rumors. Christina had little femininity in her demeanor. She had a deep voice, mostly just walked and dressed as a man in pants and boots and had her hair cut like a man. She had a distinct preference for erotic art, literature and authors like Pietro Aretino . When she was 22 years old, she knew the Ars amatoria and some of the epigrams by Marcus Valerius Martialis by heart. It was sometimes assumed that she was lesbian or bisexual . In particular, her affection for her lady-in-waiting Ebba Sparre (1626–1662), which lasted from 1644 to 1662, is documented in contemporary sources, for example in her correspondence. On the other hand, one suspected a love affair with her close confidante Cardinal Decio Azzolini , who therefore had to answer several times before the Pope. In her youth she raved about Count Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie, who took advantage of this to further his diplomatic career and then married a close friend of Christina's. She refused to marry all her life - the very idea of being dependent on a man aroused her violent dislike.

reception

The composer Count Friedrich Wilhelm von Redern dedicated his only opera Christina, Queen of Sweden (1820) to her. In 1849 Jacopo Foroni's opera Cristina, regina di Svezia was premiered at Mindre Teatern in Stockholm . August Strindberg wrote the drama Kristina about her in 1901 . The Queen's Mirror by Nina Blazon is a youth novel about the story of Kristina. The Queen Christinen House in Zeven was named after her.

Monuments

Modern statue in Zeven

Portraits

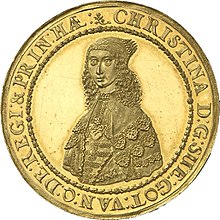

Other well-known portraits include:

- An engraving by Robert Nanteuil from 1654.

- A painting by the Dutch van Dyck student David Beck (1621–1656) from 1650 in the Finnish National Museum . Beck followed Christina to Brussels and seems to have been used by Christina for diplomatic missions, but to have been poisoned in The Hague.

- Engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar .

- A rare gold coin pictured (crowned bust, 6 ducats, 1644), which was auctioned in March 2011 for the record sum of 260,000 euros.

filming

- Queen Christine (US, 1933), with Greta Garbo directed by Rouben Mamoulian

- Christina - Between Throne and Love (The Abdication) (GB, 1974), with Liv Ullmann directed by Anthony Harvey

- Drottning Christina (Sweden, 1981), with Lena Nyman directed by Björn Melander

- Christina Wasa - Die wilde Königin (Documentary, Germany, 2013) directed by Wilfried Hauke

- The Girl King (Finland, Germany (Bavaria), Canada (Québec), Sweden, 2015) directed by Mika Kaurismäki

Works

Christina had her letters to Descartes published and posthumously her maxims. German editions are:

- Historical curiosities of Queen Christina of Sweden , publisher Johan Arckenholtz , Amsterdam and Leipzig, four volumes 1751–1760 books.google.com (works, also in French Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire de Christine de Suède , four volumes 1751–1760)

- Memoirs, Aphorisms , Munich, Winkler 1967 (editor Anni Carlson)

- Thoughts on religion and life , Düsseldorf, Schwann, 1930 (editor Hermann Joseph Schmidt)

- Collected works - autobiography, aphorisms, historical writings , Hamburg, Autorverlag Maeger 1995 (with 130 restored facsimile pages of the Arckenholtz edition 1751/2)

Correspondence with Descartes, among others:

- Lettres choisis by Christine reine de Suede , 1760, and Lettres Secrets , Geneva 1761.

literature

Non-fiction

- Veronica Buckley: Christina, Queen of Sweden. The restless life of an eccentric ("Christina, queen of Sweden"). Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-8218-4557-0 .

- Jörg-Peter Findeisen: Christina of Sweden. Legend through centuries. Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 3-7973-0514-1 .

- Hans Emil Friis: Queen Christine of Sweden, 1626–1689: A picture of life ("Dronning Christina af Sverrig"). Publisher H. Meyer, Leipzig 1899.

- Ulrich Hermans (Ed.): Christina, Queen of Sweden. Catalog of the exhibition in the Kulturhistorisches Museum Osnabrück, October 23, 1997 - March 1, 1998. Edition Rasch, Bramsche 1997, ISBN 3-932147-32-4 .

- Verena von der Heyden-Rynsch: Christina von Schweden. The enigmatic monarch. Piper, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-492-23383-X .

- Else Hocks: Christine Alexandra Queen of Sweden. Verlag Hegner, Leipzig 1936.

- Franz Schauerte : Christina - Queen of Sweden (dissertation), Herder, Freiburg 1880.

- Sven Stolpe: Queen Christine of Sweden ("Drottning Kristina"). Knecht Publishing House, Frankfurt am Main 1962.

- Veronica Biermann: From the art of abdicating. Representative strategies of Queen Christina of Sweden . Böhlau Verlag, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2012, ISBN 978-3-412-20790-8 .

- Per Sandin (Red.): Images by Kristina . Livrustkammaren, Stockholm 2013, ISBN 978-91-87594-50-2 .

Special literature

- Hanns-Peter Mederer: German musicians at Swedish residences in the 17th century. In: Concerto. Volume 6 (2004), p. 32 f.

- Katrin Losleben: Music, power, patronage: promoting culture as political action in early modern Rome using the example of Christina of Sweden (1626–1689). Verlag Dohr, Cologne 2012, ISBN 978-3-936655-96-4 .

- Laure Wyss : Leave before the sea freezes over. Fragments related to Queen Christina of Sweden. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1994, ISBN 3-85791-228-6 .

- Daniela Williams, " Joseph Eckhel (1737-1798) and the coin collection of Queen Christina of Sweden in Rome ", Journal of the History of Collections 31 (2019) .

Fiction

- August Strindberg : Queen Christine. Play in 4 acts . Ruetten & Loening, Potsdam 1953.

- Mary Lavater-Sloman : One Fate. The life of Queen Christine of Sweden. Novel . Artemis-Verlag, Zurich 1967.

- Sigrid Grabner : The rebel. Queen Christine of Sweden; historical novel . Ullstein, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-548-23711-8 .

- Gloria Kaiser : The Amazon of Rome. The adventurous life of Christina of Sweden . Verlag Seifert, Vienna 2005, ISBN 3-902406-18-6 .

- Nina Blazon : The Queen's Mirror . Ravensburger Buchverlag, 2006, ISBN 3-473-35257-8 .

- Katrin Burseg : The Pope's rebel . edition fredebold, 2010, ISBN 978-3-939674-29-0 .

Web links

- Publications by and about Christina im VD 17 .

- Literature by and about Christina in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Christina in the German Digital Library

- John J. Conley: Kristina Wasa (1626-1689). In: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Biography at Fembio

- Short biography with links to other biographies of Koniarek and Schreiber

- Queen Christine Society V.

- English-language website for her (also for the Garbo film) by Tracy Marks

- Five quotes from Christina at nur.zitate.com

- Sabine König, Anne-K. Young: Christina of Sweden . In: lespress , January 2003, p. 38 f.

- Joachim Grage : Exposures: The dubious family of Christina of Sweden in biography . In: Women's Biography. Biographies and portraits , edited by Christian von Zimmermann, Nina von Zimmermann (Mannheim Contributions to Linguistics and Literature Studies, Volume 63), Tübingen 2005

Individual evidence

- ↑ Svenskt biografiskt lexikon , Volume 21, Stockholm 1975–1977, pp. 573–580. Christina . In: Theodor Westrin (Ed.): Nordisk familjebok konversationslexikon och realencyklopedi . 2nd Edition. tape 14 : Kikarskten – Kroman . Nordisk familjeboks förlag, Stockholm 1911, Sp. 1416-1428 (Swedish, runeberg.org ).

- ↑ CV Wedgwood: The 30 Years War . Paul List Verlag Munich 1967, p. 364, ISBN 3-517-09017-4

- ↑ Documentation of the Vatican: Treaty to Renounce the Throne ( Memento of February 24, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Walter F. Kalina: Ferdinand III. and the fine arts. A contribution to the cultural history of the 17th century. Dissertation. University of Vienna, 2003, p. 231 f.

- ↑ Klas Åke Heed: Ny svensk teaterhistoria. Teater före 1800. Gidlunds förlag, 2007.

- ^ Julie Anne Sadie: Companion to Baroque Music. (on-line)

- ↑ James Tyler: A Guide to Playing the Baroque Guitar. Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 2011, ISBN 978-0-253-22289-3 , p. 70.

- ↑ Jochen Becker: "Deas supereminet omneis": to Vondel's poems on Christina of Sweden and the fine arts . In: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art , 1972-1973, pp. 177-208

- ↑ Queen Christina of Sweden stayed incognito in 1654 in Königstrasse on the website of the city of Minden. Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- ^ Günter Schwabe: Nickel, Goswin. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 19, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-428-00200-8 , pp. 198 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ^ Leopold von Ranke : The ecclesiastical and political history of the popes of Rome… Volume 3. (online)

- ↑ tercios.org

- ↑ Documentation of the Vatican: Treaty to Renounce the Throne ( Memento of February 24, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Arne Danielsson: Sébastien Bourdon's equestrian portrait of queen Christina of Sweden - Addressed to “his Catholic Majesty” Philip IV. In: Konsthistorisk Tidskrift / Journal of Art History. 58, 1989, pp. 95-108. doi: 10.1080 / 00233608908604229 .

- ↑ Character traits, principles and statements of Queen Christine of Sweden

- ↑ Notable Members of the Dohna Family. on: ostpreussen.net

- ^ F. De Caprio: L'entrata in incognito di Cristina di Svezia in Vaticano: cerimoniali e simboli . In: Settentrione NS 30 (2018) 187–211.

- ↑ The sword pierced her lover's throat

- ^ Iain Fenlon: Early Music History: Studies in Medieval and Early Modern Music. (on-line)

- ^ At the opening, Scipione affricano by Francesco Cavalli was performed; further works by Antonio Sartorio and Giovanni Maria Pagliardi.

- ↑ wiki.ccarh.org

- ↑ indianapublicmedia.org

- ^ Lorenzo Bianconi: Music in the seventeenth century. (on-line)

- ↑ Katrin Losleben: Kristina of Sweden. In: Beatrix Borchard (Ed.): Music mediation and gender research: Lexicon and multimedia presentations. University of Music and Theater Hamburg, 2003 ff. Status from June 15, 2006. (online) ( Memento of the original from August 30, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ; Retrieved on: October 8, 2011

- ↑ Queen Christina: Treasures in the convoy . In: Der Spiegel . No. 32 , 1966 ( online ).

- ↑ Christina's engraving of Nanteuil

- ↑ An engraving for this painting from 1729: Christina, Svecorum, Gothorum et Vandalorum Regina . ( Digitized version )

- ^ Johan Arckenholtz (1695–1777), Finnish historian and librarian

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Gustav II Adolf |

Queen of Sweden 1632–1654 |

Charles X. Gustav |

| New title created |

Duchess of Bremen-Verden 1648–1654 |

Charles X. Gustav |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Christina |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Kristina; Maria Alexandra |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Queen of Sweden |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 17, 1626 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Stockholm |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 19, 1689 |

| Place of death | Rome |