Epistemology

The theory of knowledge (also epistemology or gnoseology ) is a main area of philosophy , which encompasses the questions about the prerequisites for knowledge , the emergence of knowledge and other forms of beliefs . It also examines what constitutes certainty and justification and what kind of doubt can objectively exist about what kind of beliefs.

term

Epistemology (from Greek ἐπιστήμη, epistéme - knowledge, knowledge, science and λόγος, lógos - also science, teaching) is a word formation that goes back to the Greek. Some languages use this expression synonymously with epistemology: In English there is, for example, Theory of Knowledge next to Epistemology, in Dutch there is Kennistheorie next to epistemology. A conceptual difference was offered in the 20th century in French philosophy between Théorie de la connaissance and épistémology: The first-mentioned word should therefore rather stand for an analytical examination of the fundamentally existing possibilities of knowledge, the latter for an investigation of epochal knowledge formations, the so-called Epistems , and their Influence on the Conceptualization of the World. The French spelling épistémologie is sometimes used in German to denote special French research. However, these distinctions are hardly maintained any more, the terms are increasingly being used equivalently.

The German word epistemology did not become more common until the middle of the 19th century, when a more practice-oriented, more theory-remote approach to knowledge in the natural sciences split off from the philosophical, more theoretical. In the discussion with Immanuel Kant (namely in the work of Wilhelm Traugott Krug ) the term was pre-formulated at the beginning of the 19th century. Philosophers such as John Locke and David Hume had written their basic works on "human understanding" in the 17th and 18th centuries and saw themselves in a tradition that went back at least to ancient philosophy.

The conceptual formations on gnosis (from ancient Greek γνῶσις, gnosis, knowledge) in modern Greek Γνωσιολογία and Spanish Gnoseología refer back to the philosophical debate of late antiquity (see the chapter Gnostics and Christian late antiquity in more detail ).

Significance as a critical metadiscourse

Epistemological considerations deal in a larger arc with common knowledge, with the philosophy of science , with the neighboring fields of philosophy and with the epistemological discussion itself. The considerations apply less to concrete knowledge than to its classification, depending on whether it is based on sensory perceptions, logical conclusions , model assumptions with trial and error , the knowledge of the truth by revelation and reflection of innate ideas and categories is based, to name here intensively discussed classifications. Concrete stocks of knowledge are often only used as examples in the debates to discuss basic assumptions. Epistemological discussions develop explosive societal power wherever they question statements with a fundamental claim to truth.

Compared to everyday considerations, epistemological considerations often gain a dimension that can hardly be taken seriously at the same time. Wittgenstein addressed this with humor in 1951 in his Thoughts on Certainty (published only after his death in 1969):

“I'm sitting in the garden with a philosopher; he says again and again, 'I know this is a tree', pointing to a tree nearby. A third person comes along and hears it, and I tell him: 'This person is not crazy: we just philosophize.' "

For the epistemologist, unlike in everyday life, it is not the individual questionable fact that is interesting, but the consideration with which a whole range of knowledge can be questioned. The basic assumptions that exist in this area can be addressed more clearly at the same time:

“It would seem ridiculous to me to want to doubt Napoleon's existence ; but if someone doubted the existence of the earth 150 years ago , I might be more willing to sit up and take notice, because now they doubt our entire system of evidence . It seems to me that the system is more secure than security within it. "

The specifically designed problems are called aporias in epistemology . As a rule, after a brief reflection, they prove to be insoluble with human knowledge. Thanks to their simplicity, you can meet them all the more clearly with model solutions, the consequences of which then remain manageable in the subsequent considerations.

Whether one is dreaming or waking is one of the oldest of these problems. The fundamental answers are exciting - such as those of solipsism (from the Latin “solus ipse”, alone yourself), according to which everything that one considers to be perception only takes place in consciousness, is a single dream, and it is unprovable and therefore undecided whether there is anything besides this awareness.

From an everyday perspective , this is a questionable solution, but up to a certain point it is actually assumed: The common logic of everyday life is that the world exists and that people use sensory perception to form an image of it. However, it is known that this image is never really compared to the world. You can compare a photo with what it depicts, but not your own image of the room with it - at best you get new images of the surrounding space all the time. The theory that humans have images of the world is based - from an epistemological point of view - on conclusions from analogy and a model that is built up in the interpretation of human perceptions. You observe other people and suspect that they perceive the world (as you do). When you move, your view changes, similar to the picture in a camera display, when you pan it. It makes sense to assume that one moves in the world and in doing so creates these specific changes in one's own perceptions. Ernst Mach's opening chapter to his book Analysis of Sensations (1900) outlines this as the result of a model with further questions about the rules for models developed by physicists.

With the cited puzzle games, Ludwig Wittgenstein pointed out that individual evaluations of such questions apply in everyday life. The two philosophers preferred to make it clear to the casual passerby that they did not really doubt the existence of trees, but "only philosophized". At the same time, they assumed that the passer-by had two categories for the same doubt, just like them: Either they are philosophizing here, or the doubt is a sign of a loss of reality, as it is sometimes shown by accident victims in acute stress reactions when what happened seems clearly unreal to them. In the case of the accident victim, one accepts the interpretation that what just happened is not true, as a temporary evasive maneuver, known as dissociation . If someone suspects in the long term that his thoughts are being controlled from outside, he is no longer free in his decisions, he hears voices, his world is determined by imaginations, one changes the classification of this view in everyday life. A paranoia may be here. As these examples make clear, culture does not simply provide a simple epistemology - and certainly not a coherent one: in one and the same culture, the feeling of hearing voices in the head, of being controlled in behavior, can be considered pathological classified and recognized as a religious experience. Even here one will again share and appreciate certain religious experiences and pathologize others as religious madness . Everyday logic is precisely not determined by any fundamental epistemology. Even less do we see the perception of reality as simply subjective. You continuously provide information about your own view and perception of situations and intervene responsibly if someone in this environment no longer develops culturally or personally controlled perspectives.

In contrast to everyday thinking, philosophical epistemology unfolds as a “theoretical”, scientific discussion. Considerations made in this second framework do not collide with private perspectives (as they did in Wittgenstein's example with the garden fence). If successful, they collide systematically and potentially explosively with publicly represented points of view. The philosophical discipline celebrates its social explosiveness itself with the technical history, to which the process belongs, which the city of Athens 399 BC. Against the philosopher Socrates . He was accused of attacking the certainties of state and religion with his questioning philosophizing to the detriment of young people. Socrates let himself be executed voluntarily, more willing to submit to a wrong judgment than to make up for an injustice by another, that of his flight from responsibility. A heroism of its own could be celebrated here until later paintings of the nude. Giordano Bruno's execution at the stake in 1600 and Galileo Galileo's “Eppur Si Muove” are similarly handed down as references to the societal explosiveness of epistemological reflection.

The philosophical analysis of knowledge established in public is a tricky one , since epistemology appears with it as a metadiscussion : it questions the foundations of other discussions. In an explosive case, it does this in places where “undoubted truths” are dogmatically proclaimed. In terms of the history of philosophy, the arguments in which epistemologists support public perspectives are just as interesting. The proof of God formulated by the natural sciences of the 17th century effectively not only acts as an underpinning of religion, it indirectly asserts that the religion of revelation remains epistemologically problematic and offers philosophy as a universal alternative.

Thirdly, the limits of epistemology are reflected in the epistemology itself. Wittgenstein's late reflections only raise further questions here. In 1922, in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, he had demonstrated that man, whatever he perceives of the world, can translate into statements about facts. The project was exciting in terms of its completeness; At the same time, it made it clear that statements on morality and causality did not formulate facts, but belonged to a completely different project than that of depicting the world. Wittgenstein occupied himself with the question of the relationship between language and the world in thousands of small observations over the next few decades, which made problem areas recognizable. With the considerations of About Certainty , he finally questioned that epistemology begins where doubt about reality begins. One and the same doubt can gain different status in different "games" (Wittgenstein spoke of " language games " in reference to the fact that people treat each other according to different rules in different situations). One would only know practically how the game of doubt works - differently depending on the type of doubt (the Napoleon example) and differently depending on the situation (about which the philosophers agreed with the passer-by). Read in terms of the history of philosophy, the examples incorporate a thesis of pragmatism (that knowledge proves itself in practical situations). They turned it around: doubt also works in practice. In the history of philosophy, on the other hand, this consideration preceded postmodern theories, according to which there is no closed world view in linguistic exchange.

Field of scientific method and theory reflection

The epistemology gave decisive impulses to the modern sciences, which in turn have played a decisive role in shaping epistemology itself in Europe over the past five hundred years. The epistemological discussions of theoretical physics, biology and mathematics have been particularly influential. A series of works in physics from the late 19th and early 20th centuries marked the upheaval in the own specialist debate in epistemological chapters that preceded the investigations. Heinrich Hertz 's principles of mechanics presented in a new context (1891–1894) and several of Ernst Mach's books show statements that are milestones in the philosophical debate today. In contrast, the method chapters of regular scientific work mostly (without claiming the word epistemology) focus on the justification of work done. They combine methodological reflection (with which experimental set-ups or investigations were attempted, which proof to provide) with a theoretical discussion (which basic assumptions were made). German studies have similarities with scientific studies to define the scope of the findings.

The philosophical debate - this is its own method - usually uses abstractions ; discussions are based on examples. With a view to the examples, one makes prognoses about what reality must be like in order to behave in this way in the investigation. In the interesting case, the theoretical basic assumptions provide research impulses. Arguments are required that they open up to a “ reasonable ” reflection: Anyone who understands the prerequisites of an argument, its premises , in their implications (understands what follows from them for research) should theoretically be able to understand the following considerations in a similar way to a calculation in mathematics with an understanding of the basic arithmetic operations . Epistemology grants authorities and institutions no further power in judging arguments. In practice, discussion participants are required to know who has already carried out a particular argument. The arguments themselves are judged in terms of their logic . Settlements can be rejected if they can be proven to have fundamental consequential problems. The exchange takes place primarily with a view to assumptions. Their consistent analysis aims at the respective ultimate justification, the justification that remains when one questioned each answer on its own assumptions.

The study of epistemology requires a willingness to systematically question assumptions and a historical occupation with the subject. Most debates are only understandable in their explosiveness to outsiders when they know which thoughts have already been played through. Wittgenstein's example of the philosophers in the garden is an anecdote in everyday life . In the field of epistemological considerations, it takes up a question that was also discussed in Plato's and Descartes' allegory of the cave , in order to focus the more detailed question on individual aspects (in the concrete constellation on how doubts work in everyday life and among philosophers and to what extent both areas of the Doubt related). The preoccupation with epistemology as a pool of considerations enables discussion participants to assess what the example is about. At the same time, the history of epistemology, like the history of literature and art , has become the subject of interest in a history of epochal states of mind over the past two centuries.

Debate of historical significance

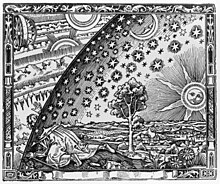

In Western Europe, the history of epistemology gained importance as a yardstick for intellectual and cultural progress in the larger process, with the sciences becoming the central provider of public discussion. In the 1780s, Immanuel Kant noted a decisive breakthrough for the beginning of the modern age: a " Copernican turn " took place with the step towards a heliocentric worldview. The human being had to relocate himself in the universe. Scientific research and modern epistemology would have made the following intellectual breakthroughs possible. The 19th century took over the perspective offered by Kant in the 1780s and pursued competing readings of the epochal achievements and their significance in the history of ideas . The writings of Auguste Comte became influential with their drafts of his three-stage law and his encyclopedic law of human intellectual development from a historical perspective.

The current technical history that caused this is restricted to the western strand of discussion that led to western-style academic life. Asiatic philosophy is sometimes conceded an opposing position, a fundamentally different way of thinking, to which the confrontational argumentative game remained alien and which therefore did not gain comparable dynamics. The conventional western history offerings mostly separate ancient , medieval and modern times as epochs. In fact, regardless of the theories to be recorded, differences in the organization of the debate, in its overall institutional structure, and with them peculiarities of Western development can be discerned.

- Ancient epistemology developed without the framework of international university research (which emerged in the Middle Ages) and without repercussions in the natural sciences (which only became more important in the late 19th century). Most decisive here is a discussion of competing schools, in which aesthetic and ethical arguments played a major role.

- The Middle East and Europe took a separate path with the triumphant advance of Christianity and Islam, two religions which, on a shared historical basis, declared the search for a coherent explanation of the world to be binding. In both cultural areas, international research has been working on the universal integration of knowledge since late antiquity. For Christianity, Augustine is one of the people here who ensured that new thinking took over ancient philosophies.

- The modern age is marked by a clear move away from the Middle Ages formulated in retrospect from 1500 onwards. This was visibly reflected in the shifting of the debate. After 1500, projects of the theologically oriented philosophy of scholasticism found increasing competition from non-theological, scientific, secular research - it not only provided its own attempts to prove the existence of God , but also explanations of nature and historical offers that broke with the Bible. The 19th century intensified the confrontation with the restructuring of the scientific community. The new subjects of the natural, human and social sciences took over essential parts of the former theological field of debate. Since then, epistemology has been continued in them.

- If there was a consensus for the Middle Ages as for the 19th century that epistemology strived for a true and complete knowledge of the world, then in the late 19th and early 20th centuries the perspective was considerably relativized: demands like those of truth were emerging the center of scientific and philosophical epistemology. New demands arose, such as the practical use of knowledge regardless of its truth. Here, projects of evolutionary epistemology (which define knowledge as the continuation of biological adaptation to the environment) agree with cultural-historical explanations that certify knowledge and the theories on which they are based have special benefits in a respective historical argumentation framework.

The main advantage of the historical perspective on epistemology in philosophy studies is that it allows the value of individual positions (as answers and counterproposals) to be grasped more clearly in historical contexts of debate.

A Discourse of the Politically Pluralist City-States: Epistemology in Antiquity

The cultural area of antiquity - the area of the states around the Mediterranean Sea - was decidedly more pluralistic than the occidental one that emerged from it in the first centuries AD. Although it produced a large number of epistemological offers, including a debate which Plato and Aristotle found its written fixation, which continues to the present day, epistemology did not gain any potential in it with which it could serve as a basis for a culture of international scientific progress .

The philosophical project only gained explosive power when, with Christianity and Islam, it became the object of a theological system striving for unity and universal significance, which was expanded on a missionary basis. Here Christianity differed fundamentally from Judaism, whose philosophical debates also had little international impact. Religion was local and individual in the ancient culture. Individual city-states worshiped gods with a local focus, who were believed to have a special bond with the city. Individual religious cults gained supra-regional charisma in trade through the use of mercenaries and the deportation of slaves and established themselves in all the larger places that were connected by the trade network. None of them developed an organizational structure from which a scientific enterprise could have emerged.

Centers of knowledge were well-known libraries like the Library of Alexandria . Otherwise philosophy was practiced in schools, the so-called academies , which in particular met a demand for rhetorical instruction. Here teachers taught argumentative competition as an art. The politics of Athens and Rome took place in public arenas. The political elite trained for them and needed justification options for them that would be obvious to the audience even in a marketplace. Different theorems were defended at the competing academies and answers to opposing ones were sought. For that reason alone, the debates were typically associated with an art of ethical persuasion. The antiquity did not build - formulated in the larger perspective - a system of universities in which knowledge would have been in constant cross-border comparison, although it was technologically superior to the early Middle Ages. There was natural science , but no globally connected research that shared the latest findings and produced a consistent background model of reality. Significantly enough, all of Rome's most famous philosophers were not epistemologists based on the Greek model, but moralists, statesmen and rhetoricians. Rome's technological progress was based on a craft engineering, not on an explosive amalgamation of epistemology, basic research and a centrally represented worldview. The offerings of Greek epistemology, which are still discussed today as basic epistemological options, actually lost their importance before the Middle Ages.

Pre-Socratic philosophy

The epistemologically most exciting area is usually referred to as pre-Socratic philosophy. It comprises several dozen names, of which mostly little more than the locality and one or a few central claims have been passed down that indicate that schools competed against each other in an exchange in which nationally known premises served as trademarks.

In retrospect, some of these positions appear modern, which is mainly due to their rediscovery in the early modern period. Modern philosophy provided itself with representatives of radical thought options. For the early modern scientists, the formulations of a potentially atheistic atomism together with the thesis that the world existed materially without being created were exciting . The far larger range of philosophies to be recorded here seems to be borne by the working of universal harmonies of thoughts through the matter of spiritual substances flowing through. Mathematics and music as the art of numerical proportions play a role in traditional arguments. The achievements in the field of geometry testify to a fascination with evidence processes that take place in a logical space, but obviously apply from this to the visible world.

In retrospect, the various theorems have in common that, even where they are reminiscent of modern particle physics and their modeling, they ultimately do not arise from empirical research in the modern sense. Theoretical considerations gained practical value above all through mathematics, through which they inspired a strongly theoretical engineering science. Thinking about mechanical laws, leverage, power transmission, which is noticeable in Archimedes (287–212 BC), refers to the traditions of a philosophy in which mathematics and epistemology were closely linked.

Plato

The two philosophers of antiquity who had a lasting impact on epistemological thinking a few centuries later are Plato and Aristotle. With Plato's rendering of the conversations, which he ascribed to his teacher Socrates , the fundamental doubt became the starting point for the discussion: although Socrates claimed that he was ultimately only certain of his ignorance - his dialogues, however, constantly led the discussion partners to develop systems in which In the end, the contradictions accumulated so blatantly that it seemed wiser to start from a completely different world: In everyday life one deals with sensual experience. In fact, there would be a much truer world behind this, a world of sane and stable " ideas ".

Under the influence of modern empiricism , the logic of Platonic reflection is not always immediately plausible. The opposite option asserts plausibility: According to it, people derive their ideas of things from intuition and experience. The ideas of things would therefore be more of an abstraction, a look at the essentials. Plato doubts about this in view of this essential and his own plausibility: The idea of what a person is is not really a mixture of the people you saw. Aspects of an idea show up in human thought as soon as there is a more thorough argument. A person remains a person when he is in a coma - so he does not have to show reason; His body can be arbitrarily deformed by a genetic defect - one effectively assumes that people simply have to be conceived and born by people, but here too they are becoming increasingly flexible. Plato refers to this in his dialogues : In the end, people always defend concepts with logical arguments rather than experience, with arguments that gain stability in relation to experience. The question that remains is where the basic concepts are obtained from, with which one thinks about the essentials. Plato's dialogues suggest that an existing reason between people makes it possible to separate reasonable from erroneous ideas. At the same time, his dialogues led to a dualism between a world of ideas and the factually existing world, in which it lags behind the ideals, offers only a random and constantly changing reality, which is so surely encountered with language precisely because language and your own considerations belong more to the realm of concepts and ideas.

Aristotle

While Plato exerted an immense influence on the world of ideas of late antiquity and Christianity, Aristotle was supposed to influence the scientific community in its organizational form much more strongly. This becomes clear if one looks at the kind of textual precipitate of the considerations. Plato offers dialogues, debates in which examples are discussed.

Aristotle, on the other hand, wrote encyclopaedically ordered stocks of knowledge under topics of research, on which one could continue to work at the same moment in increasing knowledge. With physics and metaphysics , Aristotle presented a fundamental scientific differentiation that subjected Platonic thinking about ideas and phenomena of the world to a rational order. He supplemented the other topics of ethics and politics with the area of human inventions of worlds, poetics , and logic as an investigation of the structures of argumentation.

For Aristotle, the question of the justification of the ideal forms remained decisive. His writings provide differentiations, definitions and arguments that support them. The question of perfection is a principle of order - human ideas formulate, according to the premise, implicit thoughts of the perfect object of its kind. The scientifically argued investigation must be able to explain why perfection is to be defined in this way. In this form, Aristotle also ponders why the sphere is the perfect shape and what properties a perfect tragedy must have. The rules of production arise from the explanations. Transfers determine the conclusions, for example when Aristotle concludes from the macrocosm to the microcosm , based on the basic assumption of overarching laws of form.

One can draw lines from Aristotle into the encyclopaedics of the Middle Ages, as well as into the modern natural sciences, which interpret experimental results with their own model assumptions of atoms and molecules. Modern Western Europe owes the reception of Aristotle, which began in the Middle Ages, to cultural contact with Arabia. Islamic scholarship learned from the Aristotelian writings from the 9th century.

Gnosticism and Christian Late Antiquity

The decisive steps in the international controversy, which ultimately gave the epistemology space as a basic project, took place in the exchange between the academic Platonic philosophy of Greece and the religious to sectarian currents of Gnosticism that spread in the southern Mediterranean region, in a controversy into which Finally, from the 2nd century onwards, Christianity interfered, ready to develop its own internationalist philosophical dimension with the detachment from Judaism and to offer the greater synthesis.

The Gnostic currents (from the Greek γνωσις, gnosis, knowledge) took up threads of debate from Greek philosophy, but were also open to religious thinking. The much older Zoroastrianism developed here influence. With the Persian empire it had temporarily become a state-supporting religion; its uniform cult spread across the Mediterranean. Philosophically, the offer to combine monotheism with a fundamental dualistic worldview was attractive . Whatever was observable was to be interpreted in the uniform interpretation offer as a struggle between good and evil, as a process in which the primordial fire separated from darkness, the spiritual triumphed over the physical world, producing knowledge, gnosis, in the separation of the spirit of matter if you wanted to see it philosophically. With the beginning of the cosmos, the opposite poles got mixed up. In every course of the world, knowledge had to break new ground, the spirit had to come together again. The same forces acted in every single observable process, so the offer which gave all natural processes a central principle.

Parts of the Gnostic currents gained greater cohesion in Manichaeism , which spread as a new religion in the Mediterranean region from the 3rd century onwards, before Christianity ousted it. Augustine 's Confessiones (397/98) sketch in an autobiographical retrospective the connecting lines that emerged for the observer in the North African Mediterranean area: At the end of the public discussion events, one could argue between Greek Neo-Platonism , current Manichaeism, various currents of Gnostics and Christianity.

Christianity had indeed developed in a split from Judaism, but in the mission process its claim to be the religion of a single chosen people was transformed into a universal claim: The knowledge of God was promised to all people with Christianity; the final process of the world declaration had just begun. The Messiah, who announced the end of the world, had just appeared with Jesus. With the expansion into the area of the Greek city-states, the new religion took up the current philosophical controversies. This becomes clear with the beginning of the Gospel of John , which was written in Greek at the beginning of the 2nd century - probably in Ephesus - and already in the opening offered a bridge to the Old Testament to God's act of creation and to the current philosophical debate.

| In the beginning was the word | εν αρχη ην ο λογος |

| and the word was with God, | και ο λογος ην προς τον θεον |

| and the word was God. | και θεος ην ο λογος |

| In the beginning it was with God. | ουτος ην εν αρχη προς τον θεον |

| Everything came into being through the word | παντα δι αυτου εγενετο |

| and without the word, nothing came into being. | και χωρις αυτου εγενετο ουδε εν ο γεγονεν |

| There was life in him | εν αυτω ζωη ην |

| and life was the light of men. | και η ζωη ην το φως των ανθρωπων |

| And the light shines in the darkness | και το φως εν τη σκοτια φαινει |

| and the darkness did not grasp it. | και η σκοτια αυτο ου κατελαβεν |

λόγος could stand for God's word, it was at the same moment the word for the primordial fire and reason with which the Roman Stoics , Greek Platonists, Zoroasters, Manichaeans and Gnostics handled, where they built up dualisms between the light of reason and the darkness of the material World. Early Christianity made the offer to Platonism to recognize in God the guarantor of the realm of ideas; In return, it took on a dualistic orientation, a separation of the worldly and the clerical , according to the structure of argument that Augustine finallyperceivedin the Confessiones (397/98) as the great attraction of the new religion: it had the potential to incorporate the philosophies of antiquity the Gnostic view of history and the world. If this succeeds, then beyond the secular states with Christianity a new spiritual community should be prepared, Augustine wrote about this in De civitate Dei (413-426).

In this intellectual triumphal march, Christianity took up thoughts from the entire spectrum of current debates. At the same time, however, it developed an organizational structure in which Rome and the Pope formed the center, and whose councils and controversial canon debates increasingly emitted power to marginalize competing currents. For late antiquity, this predatory competition is as significant as the thinning of the ancient knowledge base. The ancient library landscape became less important, and ancient books were no longer updated with new copies. Monasteries took over the coordination of the intellectual exchange while focusing on the scriptures of Christianity; In the end, exemplary book destruction created a distance from ancient education and led to the result that is now being discussed in science as book losses in late antiquity .

From the 4th century onwards, Christianity developed its own pluralism in a history of schisms and heretic movements , which were countered with councils , debates on the Bible canon and dogmatizations . From now on , negotiations were inherent in the system between the diverging currents . They threatened to split Christianity. The interpretation of individual Bible passages had to formulate central mediation offers. The new network of arguments was to continue into the 18th century - the Reformation movements of modern times developed out of it. The epistemology gained new meaning as a mediating debate, with which the aim was to prove the logic and validity of arguments within a supposedly closed system.

Subfield of theology: epistemology in the Middle Ages

With the end of antiquity, the Islamic and Christian cultural areas developed similar organizational structures in order to solve similar fundamental problems: Both areas defend a uniform monotheistic orientation in which they integrate the writings of Judaism. Both spaces establish religion as universally valid across national borders; this presupposes forms of organization that develop similarly ordered structures in individual states as well as ways of international information exchange that allow standards to be maintained across borders. In the end, antiquity was subject to new, flexible, completely different, comprehensive power structures. The network of monasteries, the standardization of training at monastery schools, the exchange of monks between the monasteries, the establishment of universities, international student travel - all of this became part of a form of organization that had no predecessor in antiquity. The Western Roman Empire expanded it with radiance to Northern Europe, Eastern Roman with influence on the Slavic region, Islam with influence from West Africa to India.

Rule was redefined in the new cultural area. It was no longer based on city-states, but on rulers who unified territories with the help of power structures that were also used supra-regionally. The new system is the nationwide rule that distributes privileges, creates centers of power through the founding of cities, subordinates itself to religion, founds universities and provides the infrastructure for the new universal scholarship.

Uniformity was and is above all an exciting fiction in the new system. It is sought after in theological-philosophical seminars with an effort that produces a growing pluralism of options. The field of epistemology, in its constitution as a research field determined solely by reason, strengthened the hope of an overarching understanding of truth. In Northern Europe and in the Arab world, the Middle Ages became the high time of the integration of ancient philosophy into modern thinking that aimed at unity and universality. Aristotle was commented on and became the core of the philosophical debate.

Centuries later, apologists of the "Enlightenment" were to lament the fall of antiquity and disparagingly use the word " Middle Ages ". From the point of view of time summarized under this term, the opposite can be said: The project of a universal, theologically founded philosophy that unites faith and knowledge created, on the one hand, cathedrals of reflection, encyclopedic buildings of thought of maximum size and at the same time maximum integration of all details. The philosophy of the Middle Ages was permeated by its own aesthetic: “ Subtlety ”, subtlety and complexity of the argument that can only be mastered after a long study, captivates with the works of Thomas Aquinas , Duns Scotus , Wilhelm von Ockhams and Nicolaus Cusanus . The philosophy of the modern age ultimately took over the central objectives of reflection: the theory of a uniform global knowledge taught at universities and produced by the sciences, the search for a final “ world formula ” are not the legacy of antiquity, but of the Middle Ages. The decisive considerations of how to think with closed world systems in a new radicalism began with late medieval philosophy. Occam's razor is one of these principles, the forerunner of the positivist thought movement. The problem of universals with its basic positions of realism , conceptualism and nominalism can be extended from scholasticism to the present. The division of positions, which became decisive for modernity, has its roots in the end in the epoch from which the decided distancing took place in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The Relocation of Theological Debates: Epistemology in the Early Modern Period

Book printing, which spread throughout Europe in the 1470s and 1480s, caused a comprehensive break in tradition in the sciences. Medieval manuscripts of the classical authorities were put to print. The perspective on her works changed with the text-critical editions that could now be worked on. Each of these editions reached criticism in all European scientific locations as an identically reproduced text. Scientific journals established themselves as a new discussion platform from the 17th century onwards and were in turn readable across borders. The construction of faithful editions of the knowledge handed down from antiquity became the first program. The new editions worked on the objectification of the textual tradition and the approximation of the lost original texts and created historical distance. The search for the current state of science became the project of scientific debate in the course of the 17th century. It took into account the scientific journal as a current medium and literary history as a medium directed towards the past (the word literature still stood for the sciences, not for poetry and fiction). In the new scientific market, epistemology succeeded

- to establish philosophy as a denominationally independent, fundamental truth-seeking system of research,

- From the middle of the 17th century onwards, successfully offering themselves to political interest groups who were looking for arguments with which religion could be subordinated to new forms of state organization

- to offer itself as part of the natural sciences, with which it gained new importance from the 1760s in the process of industrialization and from the 1790s in the development of the European nation states.

In retrospect, what was achieved here is considerable: theology was ousted, the sciences were finally restructured in the 19th century from the system in which there was theology, jurisprudence, medicine and philosophy to the new system in which the natural sciences, humanities and social sciences existed and engineering coexisted, fields between which theology disappeared and which all received their own epistemological foundations.

On the other hand, one must not equate the change in retrospect with a change in individual experience. It is true that the Copernican view of the world became debatable in the 16th century . The earth becomes a single planet in it, which orbits the sun in a cosmos in which there are possibly countless such worlds. But the textbooks remained true to the old Ptolemaic worldview even after the discovery. The new model was offered as an additional option; it provided advantages in the calculation of events; it hardly changed the horizon. The epochal turning point, presumed around 1500, arises primarily from the retrospective search that has been carried out today for the first evidence of the discussions; it does not coincide with what one would have experienced when visiting universities around 1700.

In the lecture halls of European universities, theological debates dominated the epistemological questions well into the 18th century. It was not primarily about proofs of God, but about biblical passages that allowed different interpretations - with an interest in core theses that had different meanings for Europe's three denominations. The history of the church became the place of this debate from 1700 onwards. Gottfried Arnold's Unpartey Church and Heretic History , published in 1699, became a milestone with a journey of discovery down to the heretical positions of late antiquity, which now inspired current epistemology. The slow change becomes more understandable when you look at the political confrontations that culminated in the Thirty Years' War and the English Civil War with its result of a parliamentary dictatorship. They all took place under the auspices of the denominational debate, even if they centered on the question of how states would organize the coexistence of their citizens in the future.

Slight deviations from standard opinions were dangerous, especially since the newly forming state institutions of the modern age were initially based on the premise that states gain stability if their citizens held the same views - they made the experience that religious pluralism exposed them to the most massive external political tears. The “free Netherlands” were not so free until the early 18th century that a Baruch Spinoza could have spoken more freely outside the circle of friends, here atheism remained the danger that would destroy the community.

Most of today's historical accounts of epistemological retrospectives to the period between 1500 and 1800 tend to clear up the complex field of debate and write stories in which modern scientific thinking prevailed in a triumphant advance of the Enlightenment . In fact, it was not possible to study science at the universities of the 17th and 18th centuries. Individual research societies, mostly groups of enthusiasts, carried experimental physics, astronomy and mathematics forward into the 19th century. The public smiled at the experiments, Jonathan Swift's satires are typical here. The living conditions only changed more drastically as a result of natural science in the last decades of the 18th century.

The usual retrospectives, which primarily juxtapose a (Franco-German) rationalism, a (dominant English) current of empiricism and a (more German) idealism of Immanuel Kant , have meaning in the larger retrospect, because they form the present structure of thought traditions grew up in the 19th century.

rationalism

The break with scholasticism began in the 17th century with rationalism , a movement that incorporated the scholastic dispute in its argumentation structures and was thus able to overcome it. The most important philosopher of the late 17th and early 18th centuries was René Descartes , whose work on the spectrum of research fields, which was brought down to a common denominator, already called for a wide-ranging discussion. Theologians, mathematicians and natural scientists had to see how they faced his claims after he brought together materialism, reflections on mind and consciousness and a proof of God of philosophical and theological significance in an explosive way. Empiricism developed among the prominent opposing positions in England in the second half of the 17th century . Almost even more important was eclecticism , which became fashionable at the end of the 17th and beginning of the 18th centuries as an answer to strict options: the position that one should use reason to take the middle path of the plausible from the consistent models. At the beginning of the 18th century, eclecticism became the fashion of the elegant, gallant circles who turned to philosophy as a branch of the belles lettres and did not publish it themselves, as did the university lecturers, who shied away from a clear connection to a system, but the systems to Took note and introduced them to their students as different ways of thinking. With eclecticism, a form of pragmatism of its own finally established itself.

René Descartes

Rationalism gained power over scholasticism above all as a philosophy that adopted forms of argumentation from theological debate. Like the scholastics, the rationalists insisted on philosophizing in logical inference that would give ideal definitions clout. The big difference to the scholastics was in dealing with authorities. Thomas Aquinas edited Aristotle - René Descartes instead combined his philosophy with the natural sciences, mathematics and a new materialism . He pleaded for a world that could be accommodated in the Cartesian coordinate system named after him . Man was like a machine. According to Descartes, the nerve cords communicated with the brain through pressure and tension. Authorities no longer had any evidential value in this world.

The arguments which Descartes offered for philosophy compatible with mathematics , geometry, and modern physics argued from the strictest of doubt. Only one fact resisted this: That in the moment of doubt one still thinks and therefore exists: “dubito ergo sum, quod vel idem est, cogito ergo sum”, “I therefore doubt I am, which means something like, I think so am I". Proof of the world and of God could be built on the mere proof of existence as soon as it was assumed that God is the perfect being. Perfection does not allow nonexistence, nor does it allow God to let you stay in a dream. The world one perceives behaves like a material world. If God was brought into play as proven, He guaranteed their existence as the very material world that is perceived.

Thomas Hobbes and his opponent Shaftesbury

From the point of view of modern empirical natural science it is hardly plausible epistemologically to explain how his existence should follow from a definition of God and from it that of the material world. Descartes, on the other hand, could assume that his evidence put the theological debate in an awkward position: the confession of a deceitful and imperfect God was not an option for the denominations over his philosophy. If, on the other hand, you got involved with him, the next moment it was unclear what you were risking. With Thomas Hobbes, on the other hand, church representatives of all denominations found it easy: he allowed himself to be branded as an atheist . His Leviathan of 1651, a theory of the state which, with a sideways glance at the English Civil War, demonstrated that all religion in the well-organized community had to submit to the crown, Hobbes put a long chapter on epistemology in front of Descartes. He was ready to follow Descartes and explain people materialistically. How man acted, egotistically, can be explained from here - neither good nor bad, simply like matter that defends its existence as soon as it realizes that it can lose it. If original sin was no longer necessary to explain human actions, the church could be assigned the task of scarcely keeping these people in fear and terror. If she was looking for another role, she created problems for the community, which has to watch to keep individual interests in check. Hobbes was unacceptable to all parties, but that was precisely why he was influential. If one wanted to represent a different image of man, one had to break with Hobbes and the Church, which assumed a no less crude basic human nature and a pernicious materialism. If you wanted to grant the church a different position in the state, you had to do it openly. Hobbes put forward arguments from which one could only safely move away if one wanted to question the basic assumptions on which state and religion were currently based.

The predicament that is constellated here for representatives of religion becomes clear with Shaftesbury , who at the end ventured the contrary thesis to Hobbes and postulated that the existing world was the best of all possible , since God could only create such a world. According to Shaftesbury, Hobbes and the churches had painted the wrong picture of human nature: man strive for harmony with all of creation. This is not to say that man is currently living according to his nature - he is actually living as Hobbes and the churches observed, selfishly. Precisely this must be explained with epistemology: it could only be the effect of the entire state and church education that tamed people with rewards and punishments in order to gain power here. Good nature is tainted by the current form of exercise of power. The considerations were again rationalistic. They proceeded from premises and inferred reality from them.

Neither the chosen premises nor the " reason " of the epistemological conclusions could not be abandoned without problems - unless it acknowledged the irrationality of belief. That, in turn, was denied in the current debate to all three established denominations, Catholics , Protestants and Reformed , all three of whom took up their own ranks against “enthusiastic” currents such as Pietism and Quietism . If theologians of the three great denominations, however, went into the final proceedings of rationalist philosophy, this foreseeably put them in an awkward position vis-à-vis their self-definition: They represented their denominations as valid according to the revealed religion and drew political claims from this in the states of Europe. The result for the 17th century was an immense penetration of the philosophical debate with objectives of theological discussions - and a discussion in which state organs increasingly made use of philosophical arguments in order to integrate denominations.

The question of freedom of will permeated the landscape of debates as epistemologically inconclusive, with the option of the most massive denominational politics being pursued in its field. The Reformed religion stood among the three denominations solely as a representative of a radical determinism : God had subjected all creation to his plan and predetermined everything that was done. On the European map, this was the religion of the free Netherlands, the Geneva city-state. In all other European countries, Reformed people like the Huguenots of France were a threatened minority. If one did not distance oneself from the rationalist debate, one threatened to open the door to a hidden theologically explosive debate, especially here. In the end, the world of natural laws was with some likelihood more deterministic (hidden Reformed) than Lutheran or Catholic.

Baruch de Spinoza

The extreme positions of rationalistic epistemology were represented by Baruch de Spinoza and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz - Spinoza with a way of thinking that logically questioned the dualism that transcendence presupposed: assuming two separate substances ( God and nature , body and spirit ) , one must postulate that they do not share any property, since otherwise they would be partially identical and therefore not separate. A substance that exists must be able to exist for itself at the same moment. If it needed another substance in order to exist, it violated its definition of an isolatable substance. At the same moment a substance could no longer produce a different type, the produced one would no longer be independent. The existing substance must therefore exist uncreated. It must be infinite - because if it were finite, another substance would have to set the limit for it, which would again bring a dependency into its existence that would go against the concept of substance. Two different substances God and nature, one creative and one created by the latter, could not exist according to these premises. The choice is “either God or nature” - “Deus sive Natura”. Some interpreters see an atheistic tendency in this alternative, which results precisely from the definition of God . For other interpreters there is a pantheistic position in the identification of nature and the real God being .

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Leibniz visited Spinoza in 1676 and argued intensively with Spinoza's monism (the theory of the unity of all matter). In his own philosophical assumptions he assumed a cosmos created from nothing by God. With a look at the smallest units of this cosmos, the " monads ", for whose properties he had logical postulates ready, he caught up with Spinoza again. Every single “monad” differs from all others in the way that it reflects the entire cosmos from its position. All matter consists of particles of this ultimately spiritual component of their existence. Considered as a whole, the world must, according to the previous conclusion, be the best of all possible worlds. From the fact that the planet earth shows deficiencies, it can be concluded at the same moment that there are innumerable other inhabited and far happier planets in the cosmos with which the cosmic overall plan is fulfilled and in which the earth with its objective deficiencies its meaningful ones Take up space for the best of the whole. (See the article Theodicy in more detail .)

One of the paradoxes of rationalistic epistemology was that in the extreme postulates it presupposed the limitation of the human understanding - precisely the understanding that it claimed to conclude. Human perception showed limits, the " mind " proved to be no less limited. “ Reason ”, which was ultimately based on inference, did not have the same limits. It did not belong to anyone, was not tied to any individual, was given in logic and mathematics , the two sciences that alone could allow humans to guess how the cosmos must be structured.

empiricism

From the empiricists' point of view , the rationalists ventured far into areas about which absolutely no knowledge could be obtained. The very different final results they came up with made it doubtful that their evidences would work. If one argued strictly against the rationalists, one could demand to stick to the sensory data and not to venture certain conclusions. As massively as the empiricists criticized the rationalists, they were so close to them on the other side when it came to the natural sciences and dealing with authorities . Descartes and Leibniz were scientists of the new age, they were members of renowned scientific academies who were open to physical experiments and had no counterparts in the Middle Ages.

The essential steps in empiricism - in philosophy, which strictly admitted to reducing all knowledge to sensory perception - took place in England.

This has little to do with the work of the Royal Society , which has become Europe's leading institution for scientific research. Comparably interesting work has been undertaken by experimental groups across Europe. More serious reasons are likely to lie in the specific field of political interest that developed for the philosophers of empiricism in England. Hobbes had already submitted the epistemological debate with a political offer. If the epistemological proof of why man was the way he was and what the community had to be able to do, the state, which relied on this argument, was offered a basis of legitimation that did not render religion useless (Hobbes left they are considered a useful instrument of power), but still subordinated to a higher, more objective, scientific calculation of the state's exercise of power.

Locke and Shaftesbury wrote epistemology, social, moral and state theory in different argumentation structures, one more systematic, the other more concerned with the aesthetics of the argument. Their offers appeared from 1689 onwards in direct confrontation with the Glorious Revolution , the second revolution of the century, which, if successful, would refute Hobbes, who, with a view to the revolution of 1641/42, had claimed that revolutions had to fundamentally destroy a state. Locke and Shaftesbury wrote in the network of party interests that emerged in 1689: While on the continent individual rulers made alliances with individual denominations in attempts to subordinate them, in Great Britain from now on parties made alliances with rulers as well as with the religions represented in the country . Both Locke and Shaftesbury, using empiricism and their social and moral theories, produced epistemology in the interests of the Whigs , who, with an interruption from 1709 to 1714, were to retain power until the late 18th century. If Hobbes had demanded the subordination of all groups to the crown, according to Locke the representatives of empiricism demanded a state that would grant the monarch power as long as he used it in the interests of the citizens, a state that might have a state church in England, who at the same time tolerated the Whigs' most important clientele, the religious dissent. The politically intricate demands presupposed theories that did not start from one of the religious groups. The new socio-political treatises and essays were underpinned epistemologically and empirically with a view to a view that convinced the individual reader in the media - the cognitive ability of the reviewers was addressed with the new lines of argument regardless of religion. Locke was immediately received on the continent, but found significantly little interest here as an independent epistemologist. Shaftesbury came into vogue on the continent in the 1760s and 1770s as the exponent of the sensibility with which a new self-discerning and responsible citizen was challenged whose perspectives new states would accept. Locke became the American Declaration of Independence philosopher in 1776 . The slow reception of empiricism on the continent seems most clearly to do with the fact that continental philosophers up until the time of Jean-Jacques Rousseau relied on achieving far more if they convinced individual rulers. An epistemology, which was mainly offered to parties in the interdenominational controversy, remained of little interest here until the 19th century.

John Locke

The project on which John Locke began with the essay concerning Humane Understanding (1690) was explosive in two places; the author noted them both on the first pages: If he claimed that everything people knew, they knew through sensory perception, then Already at this point he drew the suspicion of atheism, because it wanted to be explained first of all how God should then become the subject of human consciousness. With his insistence on sensory perception as a source of knowledge, Locke also risked a paradox: “The Understanding, like the Eye, whilst it makes us see, and perceive all other things, takes no notice of itself” - human understanding can judge as little as it can comes about how the eye can take a look at its own point of view (on this problem, see the article image in detail ).

In fact, Locke wrote a book that was distinguished from many of the rationalists' drafts by the greatest order, such as the fact that its author hardly got beyond assertions of consistency. The first part wiped all supposedly “innate ideas” off the table. Nothing was innate, otherwise people would have to share ideas - of God, matter, good and evil - worldwide in the field of innate ideas. People see things, receive ideas from them, put their ideas together, abstract from them, have them in memory, develop ideas of causality (wax melts in the heat, moments like this make causality tangible). When people repeat a perception, they are already counting; when they count, all the math has followed . According to Locke, people deal with ideas in a conscious manner and at the same time experience that there is a material outside world and a human consciousness. When people invent something new, they put pictures together to form this new thing and then go to construction. It is as clear to them as the sum of the angles in the triangle that consciousness cannot be produced by matter, since people can finally move images in consciousness even when nothing material corresponds to them. Consciousness must exist forever and uncreated, since it does not need matter. The idea of God could thus be obtained from dealing with perceptions. At the same time it must be left open what follows from a definition of God. However, before they drew conclusions from its definition, people would have already acquired the idea of its existence with things and their reflection.

Locke offered a book that barely led to evidence. Rather, he delivered a plea, according to which it must be conceivable that absolutely everything that preoccupied the human being reached human consciousness just as easily through sensory perception and dealing with it. The structure of his book is striking, from today's perspective, with the shifting of problems: In the first move he banishes all “innate ideas” from consciousness, in the second he rebuilds the world - with a look at how children learn to understand them. In the third step of the argument, he turns to language as the medium in which people formulate knowledge. The fourth book of his "attempt" is for the more complex ideas and science. Long before the “linguistic turn” that epistemology carried out with Wittgenstein in the 20th century, reference is made here to the problem of language in which the formulation of knowledge takes place - and which in turn has a considerable effect on knowledge. Locke called for human consciousness to be investigated and to understand what concepts it was dealing with - one had to examine the perceptual apparatus as well as the traditional language of thought in order to understand why people from different cultures make the world similar in some respects, perceive very differently in others. Locke formulated all of this well before the emergence of perceptual psychology and cultural anthropology . Locke inspired art. Laurence Sternes Tristram Shandy (1759–1767) was supposed to celebrate the essay concerning Humane Understanding with subtle humor as one of the most important books in world literature, since it was here that it was considered for the first time how people think: rather associative, in a chain of ideas that are not always follow the advice of reason. Science was now given a new project: that of constant self-criticism. A new subject in the philosophy of science was needed to counter the ongoing contamination of scientific knowledge by establishing concepts.

David Hume

David Hume, with his moral and epistemological investigations , offered the far more consistent attempt to build on the premises that Locke set and to question the knowledge critically . Where Locke had spoken of “ ideas ” without much differentiation , Hume separated “perceptions” from “ideas” in a forward-looking manner. Where Locke explained that what was perceived enabled one to accept causality, Hume went one step further: At best, one saw that an event A. was followed by an event B. One did not see that causality was involved. Strictly speaking, one would have to state that a sequence of events was observed here. If you go one step further in terms of scientific criticism, this would have consequences for the entire formulation of natural laws: According to Hume, you might at best have seen that so far B. has always followed A. He asked what justified the assumption that this should also be the case in the future. The theory of an ordered universe was a circular conclusion from made perceptions. Otherwise it was at least as possible that the universe was chaotic, that people had observed only a lucky streak of recurring events, so to speak. This does not contradict the fact that animals are set up with their instinct for certain regularities.

According to Hume, the identity of things and people also had to be reconsidered. One could not prove that this is "the same" person whom one met years ago - there is at most a "bundle" of perceptions with which one asserts identity, while other perceptions always speak of differences. That was a massive attack on the remnants of Platonic thought, which assigned a " essence ", a "self" to any object and assumed that one could at least deal with this purer essence in thinking.

Hume ultimately devalued reason with regard to all moral judgments. Reason may advise people to take certain actions with a view to certain goals, but when one sets other goals it advises other actions at the same time. The epistemology project ended on empirical ground not with new certainties, but rather with uncertainties and a very pragmatic approach to them. Logic was not the ultimate premise of dealing with reality. Hume asks whether it was assumed that people acted with free will and why penalties for certain forms of wrongdoing were announced. At best, people acted on a trial basis with a view to desired developments. The premises according to which action is taken were largely unmet. The project of a strict epistemology, as soon as it was carried out thoroughly, was best suited to prove the unprovability of the basic assumptions.

idealism

Idealism can be understood both as a counterposition to empiricism and as a continuation of it. In the extreme case, idealism denies that there is an outside world that can be meaningfully talked about. The empiricists start from the existence of the outside world - from this perceptions should come. The idealists, however, object: You deal with perceptions, not with the outside world. At best one can conclude from the perceptions that there is an outside world. For this conclusion, however, you need ideas and these in turn belong to the subject that evaluates the perception.

George Berkeley

The step into idealism took place on the basis of the English debate from an isolated theological position. George Berkeley was a theologian and in 1734 became Bishop of Cloyne (who worked in Oxford). The fact that Locke had hardly thought clearly - in order to demonstrate this, Berkeley only had to cite the famous predecessor in his essay towards a New Theory of Vision (1709), § 125 with his attempt to derive the triangle Euclidean geometry from perceived triangles. In any case, it was easier to think the options of the triangle first, and then to find them again in perception.

With the Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge (1710), Berkeley put the ax to Locke's explanations point by point: He asks the question of how one knows how human perception comes about - that is, that there is a material external world that exists in creates an image, first on the retina, then in consciousness. He wanted to know if there was ever more than the image in consciousness. Berkeley went one step further towards the knowing subject , following Descartes. A subject, whether you want to call it " Mind, Spirit, Soul or Myself ", the consciousness, the spirit, the soul or myself, you have to admit as soon as you think about it (as a subject).

Descartes' next step to prove the world in its materiality through a definition of God, the theologian omitted: "The table at which I write, I may say that it exists, that is, I see and feel it." Berkeley asked the question but whether one had thought through to the end, if one wanted to deduce from it that it still existed when one left the room and whether such a statement was worthwhile at all. You could say that it is worthwhile because you can send anyone into the room to fetch something from this table - you don't want to say that the table will then begin to exist from scratch. Strictly speaking, according to Berkeley, the only thing that counted again was that the table only occupied someone when and only as much as anyone perceived it. What is with him outside of his being perceived remains open.

|

Because [...] whether non-thinking things exist for themselves (absolutely), regardless of whether someone perceives them, no knowledge at all seems to be able to go there. Their being is being perceived ; nor is it possible for these things to have any existence outside of the particular consciousness or thinking thing that perceives them. |

It is not worthwhile to think about what this table is outside of moments in which it is perceived, because no one perceives it outside of these moments. The external world became obsolete in the same consideration as the assertion of its materiality: if there is an external world independent of human perception, then in precisely this form it never becomes the object of perception. You don't learn anything about them. You can imagine that it exists anyway, but you have the same reasons to think so when it exists as when it doesn't (and you just imagine the outside world). In short, if there were external bodies, it is impossible we should ever come to know it; and if there were not, we might have the very same reasons to think there were that we have now.

It must have seemed unclear at first glance what such a radical position would be for. Berkeley explicitly did not direct them against everyday ideas, but only against the philosophical considerations about matter and three-dimensional space:

|

I am not arguing against the existence of anything we can perceive, whether through the senses or through reflection. That things that I see with my own eyes and touch with my own hands exist, really exist, I do not in the least question. The only thing I deny existence is what philosophers call matter or physical substance. And in doing so, I am not doing the slightest harm to the rest of humanity, who, I dare to say, will not miss this concept for a day. The atheist, however, will miss the vividness of a meaningless word on which to build his unbelief; and the philosophers are likely to miss the grandiose manipulation with which they are now leading a completely insignificant debate. |

Berkeley now asked the question of whether one should therefore say in future that one only eats and drink "ideas" and dress in "ideas". In addition, one should perhaps stop talking about "things" any longer. At least in philosophical considerations, so Berkeley. He also asked whether this was supposed to mean that things were no longer having any effect. It cannot all consist of ideas if one distinguishes between the idea of fire and the real one, which causes burns. Thinking consistently, one has to say, according to Berkeley, that one has different ideas about fire and pain. An idea that you handle as an imagination and an idea that you handle as a "real fire".

Berkeley's reflections on religious matters had consequences. God was much easier to prove at this point than the existence of any other human being. To other people one made assumptions from certain perceptions. The idea of God, on the other hand, remained tied to all perceptions and all ideas, not to any particular perception.

All of this was conceived consequently and irrefutably, but for the contemporaries it was above all an affront to common sense , which, on the other hand, could be elevated to a saving philosophical premise.

Immanuel Kant

Ultimately, Berkeley could hardly differentiate the “idealistic” philosophy he brought into play from solipsism , from the position according to which there is only myself, the perceiving subject with my sensations (which cannot be a non-objective dream).

Following on from David Hume, Immanuel Kant entered the epistemological debate. With Berkeley, he shared the focus on the cognitive subject and on several starting positions - such as the fact that the room itself is not the object of visual perception and only takes on its shape as an imaginary, infinite three-dimensional space in human consciousness. Things in themselves , things as they are for themselves, even if no one perceives them, with all the qualities that no one has perceived in them, people never perceive them. Metaphysics as transcendental philosophy must take care of them. Unlike Berkeley, however, he noted a need to go beyond solipsism: “ Thoughts without content are empty, ideas without concepts are blind. “Pure thinking, for example in mathematics, is enriched by the“ bathos of experience ”(Kant), ie by sensuality. The understanding concepts are not receptive, but productive, that is, in Kantian terminology, "the spontaneity of the concepts", which through its creative function generates the perception when the senses are "affected" (excitation). Sensuality and concepts of understanding thus establish the “transcendental aesthetics” of the critique of pure reason .

In the terminology introduced by Kant, the empiricists insisted that there were only two kinds of judgments: Synthetic judgments a posteriori - judgments that rely on sensory perception that extends a given concept (e.g., "the ball is black" ). In addition, empiricism would like to admit analytical judgments, that is, those in which the predicates are already included in the term (e.g. “The ball is round”).

The question of a scientifically operated metaphysics was under this specification whether there were also synthetic judgments a priori .

Space, time and causality, argued Kant, are not objects of perception, but their condition. One cannot imagine how perceptual processes should run without space, time and causality. As subjects conditioned in this way, humans determine their perceptions a priori. Space and time are the inner perceptions, causality and other categories are the a priori concepts of the understanding, the ideas, on the other hand, are regulative guidelines of reason, which have no effect on perception, since they transcend it ( transcendental dialectic of Critique of Pure Reason ).

The clear demarcation from idealism, as Berkeley had led him to the edge of solipsism in the purely philosophical argument, was provided by Kant in the second edition of the Critique of Pure Reason in 1787 in the chapter "Refuting Idealism".

The argument should meet Descartes' assertion that one can only be certain of one's existence, like Berkeley's doubts about the outside world. " The mere, but empirically determined, awareness of my own existence proves the existence of objects in space outside of me, " said Kant's offer of a "proposition" that could be put in advance of the evidence of the outside world from the consciousness of one's own existence.

The argument went back to the preceding reflection on time. People need something “persistent” for time, time filling through its continued existence, and that cannot lie within themselves “ because my existence in time can first and foremost be determined by this persistence. “You don't know time if something doesn't change, while something else remains stable in the same time independently of you. “ Consequently, the determination of my existence in time is only possible through the existence of real things that I perceive outside of myself. “Kant made three notes to the proof, the first of which noted that he was using his own philosophy here to reflect on its limits. The second remark applied more specifically to the time, which was defined in sequence and precisely not in the persistent. That is not a contradiction - a passage that separates time, matter and the self from one another in the shortest possible space:

“Note 2. With this, all use of experience of our cognitive faculties in determining time is completely in agreement. Not only that we can determine all time only through the change in external relationships (movement) in relation to the persistent in space (e.g. the movement of the sun in relation to the objects of the earth), we have absolutely nothing persistent That which we could subordinate to the concept of a substance, as intuition, as mere matter and even this persistence is not drawn from external experience, but a priori as a necessary condition of all determination of time, and consequently also as determination of the inner sense with regard to our own existence presupposed by the existence of external things. The consciousness of myself in the imagination I is not an intuition at all, but a merely intellectual representation of the self-activity of a thinking subject. Therefore, this ego does not have the least predicate of perception, which, as persistent, could serve as a correlate of determining time in the internal sense: such as, for example, impenetrability of matter, as an empirical perception. "

The proof was not valid in every case, this added the third note, which noted that people can dream naturally and then cannot assign an external world to perception. In this case, however, the question must be asked where the dreamed comes from in its apparent objectivity - " merely through the reproduction of former external perceptions ", he added, and the above evidence applies to these, that they need an outside world. He asks how one can tell whether a certain experience is a dream or whether it goes back to a perception of the external world that has just been made. This can only be said in the larger perspective of all human perceptions, so the extremely pragmatic suffix: “ Whether this or that supposed experience is not mere imagination must be averaged out according to the special provisions of the same and by adhering to the criteria of all real experience . "