History of cartography

The history of cartography and cartography deals with the methods, procedures and results of the mapping in historical terms.

Definitions

History of cartography

The actual history of cartography considers the following topics in detail:

- Development of the technical processes of card production and card reproduction.

- Development of cartographic sign language, map design, map projections and map usage .

- Biographical aspects of the individual cartographers .

- Formation of cartographic schools, training traditions, institutions and organizations.

- Creation of map collections .

- Collection and documentation of the cartographic literature.

The history of cartography is a strongly interdisciplinary field of work closely related to other sciences such as the history of science , historical geography , the history of discovery , cultural history , art history , polygraphy , book history , publishing , libraries , archives , globe studies and surveying . In this sense, the history of cartography is not part of cartography, but is now a separate subject of the basic historical sciences .

Card history

In a broader sense, the history of cartography also includes map history , which researches and describes the creation and fate of individual maps or map series . In professional practice and in general linguistic usage, the two subject areas are often not clearly separated.

The map history deals with the following topics:

- Creation and development of individual maps and map series.

- Description of the history of map-related representations such as globes and panoramas .

In contrast to the history of cartography, research into individual maps is not carried out on a university level. However, dealing with the history of cartography requires precise knowledge of the history of maps and vice versa, so that neither of the two areas can be worked on and viewed in isolation.

Relationship to historical geography

Historical geography , which tries to develop past worldviews from cartographic sources, is not part of the history of cartography . Historical geography is based on research into the history of cartography and map history. For example, the most accurate possible dating and source criticism of an old map is the task of map history, without which a reliable interpretation and use of this map by historical geography is not possible.

Development of cartography and maps

The history of cartography encompasses all ages, all cultural spaces, all reproduction and printing processes, a wide variety of map types and the biographies of thousands of cartographers.

It is now assumed that maps must have been created at an early stage of humanity. These maps have not been preserved, as they may have been drawings in the sand or orally passed on, formalized descriptions of spatial conditions. Such maps, which of course require a broad definition of the term "map", were documented among the natives of Australia in the 20th century .

prehistory

In Ukrainian Meschyritsch (Kaniw) there was an engraving on a piece of mammoth ivory. It could represent the huts of the residential area and then be the oldest known map. The Paleolithic site is estimated to be around 13,000 BC. Dated.

From the time of prehistory one has almost only guesses and scant information about maps of the most primitive kind, of which almost no traces have been preserved. The oldest cartographic representation so far was found in 1963 in Çatalhöyük, Turkey, during the excavations of a Neolithic settlement. The wall painting shows the settlement around 6200 BC. With its houses and the double peak of the Hasan Dağı volcano .

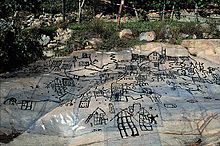

Around 1500 BC In today's Italy near Capo di Ponte in Val Camonica numerous petroglyphs were created . One of them shows a map of a place as well as animals and people on 4.16 × 2.30 m.

Early history

Diverse cartographic evidence has been preserved from ancient Mesopotamia . The oldest map representation is a clay tablet from the Akkadian city of Nuzi (today's Jorgan Tepe, southwest of Kirkuk in Iraq ). It dates from between 2340 and 2200 BC. On the 7 × 7 cm large clay tablet mountains, rivers and cities of northern Mesopotamia are drawn. The earth swims as a round disc in the ocean. In Babylonia around 1500 BC. A map of Nippur on a 21 × 18 cm clay tablet showing the city gate, various buildings and the Euphrates and inscribed in Sumerian cuneiform . The so-called Babylonian world map , a cuneiform tablet from the 6th century BC , is also very well known . Chr.

All high cultures developed maps. From Egypt is from about 1300 BC. A map of the Nubian gold mine fields on papyrus . It represents the basin east of Koptos with a main street and the temple of Amun .

Antiquity

Significantly more cartographic evidence is known from antiquity than from early history. But even these are no longer all preserved, but in some cases only indirectly proven in stories or biographies of individual scholars.

In the first place are the results from the Greek culture area. For example, Anaximander is said to have been around 541 BC. Have drawn a map of the world that has not survived. Hekataios of Miletus used this around 500 BC. For his records and other work. Among other things, he wrote the first geographically and historically exact travelogue (Periegesis) of the earth known to him. At the same time, Herodotus gave a detailed description of how to draw a map of the world in detail. The boundaries of its world horizon are Northern Europe ( Hyperborea ), the Caspian Sea , West Indies and in the south the Sahel zone . This corresponds roughly to the picture of Hecataeus. - At the turn of the century, Strabo designed a work with his 17-volume geography that not least contained a map of the world. Strabon has already specifically addressed numerous uncertainties in the information incorporated due to the source situation.

In a nutshell, the scientific preoccupation with the earth image can be traced back to two Greeks who worked at the famous library in Alexandria. On the one hand, shortly before 200 BC it succeeded. Chr. Eratosthenes of Cyrene to calculate the circumference of the earth based on the angle of the sun's rays. For this it was necessary to assume that the earth had the shape of a sphere. On the other hand, the worldview of Claudius Ptolemy should prove to be formative for the subsequent epochs . Ptolemy took over the view of the spherical shape of the earth around 150 AD and at the same time placed the earth in the center of the universe. However, based on Poseidonios , his work assumed a circumference of the earth that was much too small. Earth and country maps can already be found in the oldest surviving manuscripts of his Geographike Hyphegesis . The core of the work, however, was a directory of around 8000 positions with the attributes latitude and longitude (comparable to the coordinate directories in modern atlases).

Only a few cartographic documents have survived from Roman antiquity, including the Forma Urbis Romae and the cadastral plans of Orange . Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa had in 13 BC When the Porticus Vipsania was built, a map of the world engraved in marble was added by Pliny in his Naturalis historia as the basis of his geography. Only copies or reconstructions of this map have survived.

In addition, the Tabula Peutingeriana has been preserved, a street map of the Roman Empire unnaturally distorted from west to east with details of the military stations and distances in miles . The ancient original is lost, a copy made around the year 400 shows the conditions around 50 AD. The route map of Dura Europos found in 1923 was created between 230 and 235 and is considered to be the oldest original road map in Europe.

middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, three completely independent card traditions emerged, namely (in the chronological order of their development): Mappae mundi, portolan cards, Ptolemy cards.

Mappae mundi

European cartography at the beginning of the Middle Ages was a significant step backwards compared to the high level of knowledge of antiquity. The ancient knowledge was maintained in the Islamic world, whose cartography and mathematics would later become groundbreaking for European cartography of the Renaissance . In Europe, however, the cartographic knowledge of antiquity was largely lost. The first maps of the Middle Ages were religious representations that were not about an exact mapping of the world in the scientific sense. The oldest surviving mappae mundi date from the 8th century. They and their successors up to the 15th century were mostly made by monks and were illustrations for theological and general educational works that were copied over and over again.

The Mappae mundi can be divided into several groups according to their shape:

- The largest and best-known group is formed by the cycle maps (also called TO maps). The central location of Jerusalem in the always round map was important for this type. The upper half usually occupied Asia, while the lower left quarter was reserved for Europe and the lower right quarter for Africa. This type of card is therefore also called TO cards because its basic structure looks like a T within an O. Usually these cards are only about four to six inches in diameter. These include, in particular, the maps from the Etymologiae of Isidore of Seville and from Macrobius' commentary on Somnium Scipionis . A few TO cards, on the other hand, are exceptionally large and have a diameter of up to 3.5 m. These giant maps include the Ebstorf world map (approx. 1235) and the Hereford map (approx. 1270).

- Another group of Mappae mundi is named after Beatus von Liébana . The Beatus cards are oval in shape and slightly more decorated in terms of content than the TO cards, but without denying their Christian character. Another creator of oval Mappae mundi is Ranulph Higden .

- Last but not least, there are numerous mixed forms and independent cards that are not related to other Mappae mundi. Worth mentioning here are the world map by Andreas Walsperger (1448/49) and the world map by Fra Mauro (1459). Also noteworthy is the Tabula Rogeriana , a map of the world by the Spanish-Arabic scholar al-Idrisi , which he made in Sicily around 1150 for King Roger .

Postage cards

A portolan (ital. Portolano , derived from lat. Portus "harbor") was originally a book with nautical information such as landmarks, lighthouses, currents and port conditions. Its use is documented for the first time in 1285. In contrast, the cartographic representations are called postage cards . They are distinguished by certain characteristics: They are very precise, only the coastal outlines and the names of the port locations are entered, they are covered by a network of lines crossing each other in compass roses, they often have graphical scales . Usually the skin of a sheep or a cattle was used as a symbol carrier, which gives the portolan cards a characteristic shape. The most common are porto cards of the Mediterranean. Examples of this map category are the first map of this type, the Pisan map (last quarter of the 13th century) and the so-called Catalan World Atlas (1375).

The art of postage card making was cultivated in Venice, Genoa, Lisbon, Mallorca and other places. Towards the end of the Middle Ages, thanks to the new discoveries, not only portolan maps of the Mediterranean were made, but also real world maps in portolan style. Examples of this later period are the map by Piri Reis (1513) and the large portolan map by Diego Ribero (1529).

Ptolemy cards

In the 14th century a Greek manuscript of the geography of Claudius Ptolemy , probably more than a thousand years old, reached Italy from Constantinople and was translated into Latin there. In a very short time, copies were made of it, which enjoyed great popularity. Ptolemy himself had only drawn a few rough sketches, but his work contains written instructions and extensive tables for creating maps. The maps created on this basis - world maps and numerous detailed maps - are called Ptolemy maps . With them the work of Ptolemy was supplemented over the centuries. After 1450, Ptolemy's atlases were enormously distributed through the printing press , around 1300 years after Ptolemy.

The Ptolemy maps were seen as a significant achievement compared to the Mappae mundi common in Europe, since the authority of Ptolemy was beyond question and his coordinates were not in doubt. Numerous information given by Ptolemy was incorrect, and the maps based on them were by no means more precise than the postage maps (which, however, did not show any land areas).

It was not until the increase in global seafaring around 1500 and a new, critical way of working by cartographers that a change was made towards more realism in cartography. The cosmographers began to insert new maps (so-called tabulae novae ) in the appendix to Ptolemy's geography , but without leaving out the old maps. Ptolemy's atlases from the 16th century are therefore an impressive testimony to the change in the worldview at the end of the Middle Ages. Even Christopher Columbus was in possession of Ptolemy atlas. One of the most famous cosmographers was Sebastian Münster .

The globe of the Nuremberg scholar Martin Behaim from 1492, also called Martin Behaim's Erdapfel , can be seen as the keystone of this period, as the continents America and Australia are still missing on it.

16th and 17th centuries

From the 16th century onwards, the advances in cartography were already very noticeable. Gradually the emancipation of Ptolemy takes place, the adaptation of certain map projections , the replacement of fabulous and hypothetical animal representations on the white spots in Asia and Africa with the results of new discoveries.

World maps

In 1507, Martin Waldseemüller and Matthias Ringmann published a globe and an epochal world map as well as an “Introduction to Cosmography”. The continent name America is found on the map for the first time , which was formed from the first name of the Italian researcher and geographer Amerigo Vespucci at the urging of Ringmann - other sources name Waldseemüller . With his reports, which appeared from 1503 under the title Mundus Novus , he in turn provided a solid foundation for the geography of South America. As additional sources, a large number of Portolani in particular have been incorporated into the work that goes far beyond that as a basis.

The authoritative world map, however, was that of Gerhard Mercator from 1569, which appeared under the title Nova et aucta orbis terræ descriptio ad usum navigantium emendate accomodata . It is the first world map that is conformal . To this day, nautical charts are usually published in the image named after their developer, the Mercator projection .

Atlases

With the enormous increase in geographical knowledge of ever larger parts of the world, the spread of printing and the emergence of a rich and educated bourgeoisie, the need arose to publish maps of all regions in a standardized format. Abraham Ortelius was the first to recognize the economic potential and published the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum in 1570 . This work can be regarded as the first earth atlas . However, Gerhard Mercator was the first to use the term “atlas” for a book with maps. This work, epochal in every respect, was published in 1595 under the title Atlas sive Cosmographicae meditationes de fabrica mundi et fabricati figura .

Subsequently, the Dutch cartographers and publishers were authoritative, including Jodocus Hondius , Johannes Janssonius and Willem Janszoon Blaeu . Atlas production was actually developed into an industry. The eleven-volume Atlas Maior by Joan Blaeu , first published in 1662 , was one of the most elaborate and expensive European atlases of all. The copper plates were often inherited or, after the death of a cartographer, were auctioned off to new owners. Most of the time, the plates were used again and again for prints over the decades, so that they were worn out and outdated over time. As a result, the Dutch atlases were no longer competitive from the 18th century; French and German cartographers filled the gap in the market.

Maps

Exact maps were required for contested areas. A 1528 printed in Ingolstadt Hungary map was the World Documentary Heritage of UNESCO added: " tabula hungariae ". It was designed by Lazarus Secretarius and improved by his teacher Georg Tannstetter and provided with a scale.

Other card types

In the early modern era, other types of maps and map-related representations were also developed, the practical use of which particularly pleased travelers and traders. The travel map as the forerunner of the road atlas , the mileage disc as an early form of the distance table , the city map and the bird's eye view , the city view from a bird's eye view are emphasized. These special cartographic products served the needs of modern merchants who were traveling all over Europe and had to orientate themselves in foreign countries. This opened up additional earning opportunities for printers and cartographic publishers. So-called inspection cards were also presented to the court, either on behalf of one of the disputing parties or the court itself.

18th century

The production of maps and atlases, like printing, had become a trade. Cartographers such as Guillaume Delisle and Jacques-Nicolas Bellin in France, Johann Baptist Homann and his heirs in Nuremberg and Matthäus Seutter in Augsburg were particularly innovative in the 18th century . However, like their Dutch colleagues in the previous century, they too succumbed to the negligence of repeatedly reprinting their maps without updates, so that after years or decades there was no longer any question of current maps.

In the long term, all private cartographers were overwhelmed with the uniform topographical recording and the mapping of entire countries on a larger scale. Ordinary atlas maps were no longer sufficient for the military in particular, so that first in France and - following its example - in other countries the state began to finance the mapping of the national territory, and from around the end of the 18th century even employed cartographers as civil servants. With Jacques and César François Cassini de Thury , who completed the great triangulation of France and the large map series based on it from 1750 to 1793 , the time of precise topographical land surveys in the modern sense finally began .

At that time, however, really precise land surveys were limited to flatter stretches of land, while the high mountains were only shown schematically. Only the innovative activity of the first two farmer cartographers from Tyrol, the self-taught mountain farmers Peter Anich and Blasius Hueber , overcame this deficiency with the work on the Atlas Tyrolensis (1760–1774). The following innovations contributed to this: suitable triangulation on nearby mountain peaks, easily portable measuring tables and visors, graphic analysis only in the office, own methods of mountain projection and incidence of light from the south or west. For the first time, she and the later farmer cartographers also depicted glacier and alpine regions precisely.

19th century

Official topographic maps

The 19th century is actually the century of the great land recordings. By then, numerous states had been mapped topographically, but the results were not printed as maps. That changed around 1800. In the German-speaking area, the Prussian New Admission , the Franzisco-Josephinische Landesaufnahme in Austria and the Dufour map in Switzerland can be named as examples. The Dufour map became the model for numerous map series of other areas, as its representation of the terrain by means of shaded hatches with an illumination direction from the northwest was considered very clear. For these early official map series, the dominant reproduction technique was copper engraving .

From the middle of the 19th century it also became common to print cards in multiple colors. The reproduction technique used for this was lithography , invented in 1798 , which had an extremely beneficial effect on the clarity and cost of map production , especially with geological maps . One of the first color-printed topographic maps was the topographic map of the canton of Zurich , then the Swiss Siegfried map and the topographic maps of Baden and Württemberg. Although the three last-mentioned works are called Topographical Atlas , in today's parlance they are not atlases but maps .

Private mapping

Of course, the above-mentioned developments did not remain without influence on the private industry. Numerous so-called geographical institutes such as those in Gotha , Weimar and Leipzig issued maps. Justus Perthes' geographical institute in Gotha was in the lead for a long time , where the geographer August Petermann published the journal Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen from 1855 onwards. It quickly became the most important German-language specialist journal in geography, in which all the important geographical discoveries of the 19th and 20th centuries were published. It contained current maps in every issue, showing a hitherto unknown high criticism of the sources.

Germany became a leader in atlas cartography in the 19th century . From 1817, Adolf Stieler's hand atlas was published by Perthes in Gotha, followed by Andree's general hand atlas at Velhagen & Klasing in Bielefeld, Meyer's large hand atlas at the Bibliographical Institute in Hildburghausen (later in Leipzig) and Westermann's school atlases in Braunschweig. Other publishers of large atlases that are still active today are Bartholomew in Edinburgh, De Agostini in Novara, Freytag-Berndt & Artaria in Vienna and Rand McNally in Chicago.

The problem of terrain mapping can be seen as one of the main cartographic themes of the 19th century. Although the contour line (in the form of a contour line) was invented as early as the 17th century, it did not appear regularly on maps until around 200 years later. The contour line was precise, but not particularly clear. Therefore, especially in Switzerland and Austria, new possibilities were sought and finally found in the first half of the 20th century in various types of oblique light shading .

Sea representations on world maps

Under the influence of the systematic mapping of coastlines by state survey expeditions and the increasing research interest in the oceans, the representation of the oceans on world maps changed in the 19th century. The previously largely empty areas were increasingly filled with information, for example, on currents , ice drift , whale bottoms , seagrass fields or ship and telegraph connections. The world maps enriched in this way popularized the then new understanding of the earth as a systematically coherent whole for which the oceans played a unifying function, not a dividing one, and thus acted as media of globalization .

20th century

International cooperation

Proposed in principle by Albrecht Penck in 1891 , the specifications for an international world map 1: 1 million were established in 1913 . The project made good progress in the first half of the century, but suffered a major setback as a result of the Second World War. In 1953 the UN took over the project. Although it has since been discontinued and has never been finished, the map series still covers all of the major land areas on earth. Its importance lies above all in the worldwide attempt to standardize maps and to process them jointly by institutions of numerous countries.

The development of cartography into an academic discipline was heralded with the work Die Kartenwissenschaft (1921–1925) by Max Eckert-Greifendorff . In 1925, the world's first institute for cartography was founded at the ETH Zurich by Eduard Imhof . In 1959 Imhof was also the spiritus rector and the first president of the International Cartographic Association .

Change in conventional card technology

As a result of the needs of the military during the two world wars, many cartographic innovations were developed. On the one hand, this included new types of maps such as maps of the positions of the enemy (and one's own defense lines), which had to meet the requirements of the artillery and had to be updated quickly. From the 1920s onwards, aerial photographs were taken and these were then stereophotogrammetrically evaluated.

On the other hand, the Second World War in particular marks a turning point in map technology . From around the 1930s onwards, experimentation was carried out everywhere with new or modified variants for reproducing maps. But the extraordinary need for cards during the Second World War triggered a real innovation surge. In order to speed up the production processes, the German Wehrmacht , for example, replaced the cartographic techniques (copperplate engraving or lithography) that had been used until then in favor of the original production on transparent foils. Astralon in particular, a polyvinyl chloride character carrier invented in 1938, quickly established itself in private cartographic publishers after the war.

Layer engraving on glass was invented by the Dutch in Indonesia as early as 1912 . The process was then used sporadically in the USA and Sweden, whereupon it was first introduced on a broad basis in 1953 in the Federal Topography for the production of the national map of Switzerland . This made the process widely known and distributed worldwide under license until the 1980s.

Introduction of digital cartography

From the 1960s onwards, the computer was still cautiously used in cartography and by the 1990s at the latest it replaced all conventional map techniques practically universally. The job description changed from the mainly manual, and depending on the point of view, even artistic activity radically to a very technical, albeit less varied, work in front of the screen.

The availability of satellite images obtained by spy and earth observation satellites , which began almost at the same time as the introduction of computer technology , further accelerated the change in cartography. For areas that are difficult to access or contested, or in the event of disasters, maps are requested and updated at ever shorter intervals. Geographic information systems , which mostly combine remote sensing data and mapped data, have been widespread in Europe and the USA since the 1990s.

21st century

The still young century saw the establishment of route planners on CD-ROM and as online services as well as GPS navigation systems on a broad basis , which are reflected in many commercial products. Today, more interactive maps are created on the Internet every day than have been printed cumulatively in past centuries.

The development of mobile end devices, mostly navigation devices with graphic displays, are currently the focus of numerous research at cartographic institutes. However, research on virtual reality or augmented reality is also represented in cartography today, but is increasingly being carried out by non-cartographic software companies due to the technical or financial input required. Google Earth is currently the benchmark for 3D map display for home use on standard PCs .

Development of the history of cartography

Serious research into the history of individual maps and map series began at the beginning of the 19th century. With the advent of lithography it became possible to produce reproductions of old maps in a rational way. In this respect, the Portuguese Manoel Francisco de Santarém (1839) and the Finnish-Swedish researcher Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld did well with the works Facsimile-atlas to the early history of cartography (1889) and Periplus (1897).

After the First World War, the exiled Russian Leo Bagrow began to grapple with the historical roots of cartography. From 1935 until his death in 1957, he founded and directed the magazine Imago Mundi , which still appears annually in English and is one of the most influential magazines in the field. In the German-speaking countries, the magazine for map history Cartographica Helvetica has been published every six months since 1990 .

In 1964, the first International Conference on the History of Cartography (ICHC) took place in London. This has been held in odd years since 1967 and, with around 200 participants, is one of the most important events in the field (8th ICHC Berlin 1979, 16th ICHC Vienna 1995, 22nd ICHC Bern 2007). The lectures in the ICHC series are not systematically published. The Cartography History Colloquium was established in German-speaking countries from 1982 under the aegis of Wolfgang Scharfe , and has since been held in even years with around 120 participants. These lectures will be published in conference proceedings.

The lexicon on the history of cartography , which was published in 1986 by Ingrid Kretschmer , Johannes Dörflinger and Franz Wawrik , is still fundamental . The knowledge of the subject is dealt with in articles that are arranged alphabetically and contain a maximum of five pages. The conception of the work The history of cartography , which was founded in 1987 in the USA by John Brian Harley and David Woodward and has not yet been completed, is different . The articles in this encyclopedia are arranged by subject and sometimes comprise several hundred pages.

The specialist literature on individual aspects of cartography and map history is now unmanageable. Since the 1990s, there has also been a noticeable boom in popular science books on the subject.

Related topics

literature

Trade journals

- Cartographica Helvetica . Specialized magazine for map history . Cartographica Helvetica, Murten 1990 ff. [Every six months]. ISSN 1015-8480

- Imago Mundi. Journal on the history of cartography . Imago Mundi Ltd., Berlin [now: London] 1935 ff. [Annually].

- Kartographische Nachrichten 1951 ff. [6 issues per year].

Lexicons

- JB Harley, David Woodward (Eds.): The history of cartography . University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1987 ff. [English; 6 volumes published so far], online edition of the first three volumes

- Ingrid Kretschmer et al. (Ed.): Lexicon on the history of cartography. From the beginning to the First World War . Vienna: Deuticke, 1986. ( Cartography and its peripheral areas , Volume C). ISBN 3-7005-4562-2

- Werner Stams: history of cartography . In: Bollmann, Jürgen; Koch, Wolf Günther (ed.): Lexicon of cartography and geomatics . Volume 2. Spectrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg 2002, ISBN 3-8274-1056-8 , pp. 4-11.

- Helen M. Wallis: Cartographical innovations. An international handbook of mapping terms to 1900 . Map Collector Publications, [Tring] [1987], ISBN 0-906430-04-6 .

Monographs

- Leo Bagrow, RA Skelton: Master of Cartography . 6th edition. Gebrüder Mann, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-7861-1732-2 .

- Peter Barber: The Book of Cards. Milestones in cartography from three millennia . Primus, Darmstadt 2006, ISBN 3-89678-299-1 .

- PDA Harvey: The history of topographical maps. Symbols, pictures and surveys . Thames & Hudson, London 1980.

- Ivan Kupčík: Old Maps. From antiquity to the end of the 19th century. Translated into German by Anna Urbanová. Artia Publishing House, Prague 1980.

- Vitalis Pantenburg : The portrait of the earth. History of cartography. Stuttgart 1970 (= Kosmos Library , 266).

- John Pickles: A History of Spaces: Cartographic Reason, Mapping, and the Geo-coded World. Routledge, 2003.

- Gerald Sammet: The measured planet. Picture atlas on the history of cartography . GEO published by Gruner + Jahr, Hamburg 1990, ISBN 3-570-03471-2 .

- Ute Schneider : The power of cards. A history of cartography from the Middle Ages to the present day . 2nd edition, Primus, Darmstadt 2006, ISBN 3-89678-292-4 .

- Traudl Seifert: The card as a work of art. Decorative maps from the Middle Ages and modern times (exhibition catalogs / Bayerische Staatsbibliothek; 19). Uhl, Unterschneidheim 1979, ISBN 3-921503-55-8 .

- Michael Bischoff , Vera Lüpkes, Rolf Schönlau (eds.): Weltvermessers. The golden age of cartography (exhibition catalog / Weser Renaissance Museum Schloss Brake 2015). Sandstein, Dresden 2015, ISBN 3-95498-180-7 .

Web links

- Meta page on the history of cartography [structured, professionally supervised collection of links; English]

Single receipts

- ^ Porticus Vipsania . In: Samuel Ball Platner, Thomas Ashby: A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome . Oxford University Press, London 1929, p. 430 ( online ).

- ↑ Pliny, Naturalis Historia 3.17.

- ↑ Tristan Thielmann: Source Code of Orientation. A design by Leon Battista Alberti. In: Sabiene Autsch, Sara Hornäk (Ed.): Spaces in Art. Artistic, art and media studies designs. transcript Verlag, Bielefeld 2010, ISBN 978-3-8376-1595-1 , pp. 231–250, here: p. 235.

- ↑ This map of Hungary is kept in the Széchényi National Library in Budapest. The printing privilege granted to Tannstetter (with the humanist name Collimitius ) can be seen at the bottom left .

- ↑ So assessed by Eugen Oberhummer , Franz von Wieser (Ed.): Wolfgang Lazius. Maps of the Austrian lands and the Kingdom of Hungary from the years 1545–1563 . Innsbruck 1906, p. 39.

- ↑ Wolfgang Struck, Iris Schröder , Felix Schürmann, Elena Stirtz: Maps of the seas. A world creation. Corso, Wiesbaden 2020, ISBN 978-3-7374-0763-2 .