Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany

| Basic data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany |

| Short title: | Basic Law |

| Abbreviation: | GG |

| Type: | federal Constitution |

| Scope: | Federal Republic of Germany |

| Legal matter: | Constitutional law |

| References : | 100-1 |

| Issued on: | May 23, 1949 ( Federal Law Gazette p. 1 ) |

| Entry into force on: | May 24, 1949, midnight |

| Last change by: |

Art. 1 G of September 29, 2020 ( Federal Law Gazette I p. 2048 ) |

| Effective date of the last change: |

October 8, 2020 (Art. 2 G of September 29, 2020) |

| GESTA : | D069 |

| Weblink: | Full text of the Basic Law |

| Please note the note on the applicable legal version. | |

The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany of May 23, 1949 (short German Basic Law ; generally abbreviated GG , more rarely also GrundG ) is the constitution of Germany .

The Parliamentary Council , which met in Bonn from September 1948 to June 1949 , drafted and approved the Basic Law on behalf of the three Western occupying powers . It was adopted by all German state parliaments in the three western zones with the exception of the Bavarian one. A referendum did not exist thus. This and the renunciation of the designation as a “constitution” should emphasize the provisional character of the Basic Law and the Federal Republic of Germany that was founded with it. The Parliamentary Council was of the opinion that the German Reich continued to exist and that a new constitution for the entire state could therefore only be adopted by all Germans or their elected representatives. Because the Germans in the Soviet occupation zone (SBZ) and in Saarland were prevented from participating, a "Basic Law" was to be created for a transitional period as a "provisional partial constitution of West Germany ": The original preamble raised the will of the German people for national and state unity emerged. The Saarland became part of the Federal Republic on January 1, 1957 and thus came under the scope of the Basic Law. With the reunification of Germany on October 3, 1990, it became the constitution of the entire German people (→ preamble ).

The Basic Law fulfills the criteria of a substantive constitutional concept from the start by making a basic decision about the form of the political existence of the country: democracy , republic , welfare state , federal state as well as essential principles of the rule of law . In addition to these basic decisions, it regulates the state organization , secures individual freedoms and establishes an objective system of values .

Based on the experience of the unjust National Socialist state, the fundamental rights enshrined in the Basic Law are of particular importance . They bind all state authority as directly applicable law ( Art. 1 Para. 3). As a result of their constitutive definition, the fundamental rights are not just mere state objectives ; rather, as a rule, there is no need for a judicial authority to exercise them, and legislation , executive power and jurisdiction are bound by them. From this derives the principle that the fundamental rights are primarily to be understood as the citizen's defensive rights against the state, while they also embody an objective system of values that is a fundamental constitutional decision for all areas of law. The social and political structure of the state-constituted society is thus constitutionally established.

As an independent constitutional body, the Federal Constitutional Court preserves the function of fundamental rights, the political and state-organizational system and develops them further. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany in its current form stipulates a perpetuated and legitimized state constitution. It can only be replaced by the people adopting a new constitution ( Art. 146 ).

etymology

The German word Basic Law first appeared in the 17th century and is considered by linguists as a loan translation or Germanization of the term lex fundamentalis coined in the Latin legal language ; “Basic Law” therefore means the “fundamental [state] law ”.

All other laws that do not have constitutional status are also referred to as simple law.

History of origin

Between the end of the war and the London Six Power Conference

Even before the London Six Power Conference , the Allies asked politically active Germans in the occupation zones to think about a new state structure for Germany. On June 12, 1947 , the British military governor , Sir Brian Robertson , called on the zone advisory council set up in his occupation zone to comment on the structure of a post-war German state . While the intention of the SPD to create a strong central instance still seemed relatively promising in this zone of occupation , in southern Germany, with its strong federalist traditions in Bavaria , Württemberg and Baden, the view that the national socialist unitary state would prefer to return to the traditional German division into To introduce countries with statehood and independence. The term "Federal Republic of Germany" was first used by the French occupation authorities in Württemberg-Hohenzollern in May 1947.

While the state representatives were able to participate relatively strongly in the constitutional discourse, the leadership of the parties remained largely without influence, especially since they were not yet able to be constituted across Germany and were thus eliminated as state-related interest groups. Nevertheless, in 1947 and 1948 there was already a clear difference between the Union, which in April 1948 presented its “Principles for a German Federal Constitution” with a strongly federalist character, and the SPD, which in 1947 condemned all separatism with its Nuremberg guidelines the "imperial unity" absolutely wanted to preserve.

London Six Powers Conference

The conference held in London in February and March and from April to June 1948 between the three Western occupying powers France , the United Kingdom and the United States of America and three direct neighbors of Germany, the Netherlands , Belgium and Luxembourg , dealt intensively with the political Reorganization of the occupation areas in West Germany. Because of the beginning of the Cold War, the victorious powers met without the Soviet Union for the first time .

The three occupying powers initially pursued quite different interests: While the centrally organized United Kingdom had no preferences regarding the question of “central government or federalism?”, But rather aimed at unifying the Trizone with the Soviet-occupied zone as smoothly as possible , the United States pleaded for it a German federal state consisting only of the Trizone. For the French, on the other hand, the main objective was to weaken every German state as clearly as possible: Accordingly, they advocated the longest possible occupation without the establishment of a state and the inclusion of the Saarland in the French state association. However, since they could not prevail with the position of preventing a state from being established, the French advocated a federal state structure with international control of the coal and steel industry .

Finally, the final communiqué of the conference contained the call to the Germans in the western countries to build a federal state . However, this federal West German state should not be an obstacle to a later agreement with the Soviet Union on the German question .

This decision was only confirmed by France after massive pressure from the other two allies and an extremely tight vote (297: 289) in the National Assembly .

Frankfurt documents

After the London resolutions had been received rather negatively in Germany , the Frankfurt documents presented to the Prime Minister on July 1, 1948 were to be kept in a tone more friendly to Germany. In addition to the announcement of an occupation statute, the most important of the three documents, Document No. I, contained the authorization for the Prime Minister to convene an assembly that was to work out a democratic constitution with basic rights and a federal structure . This then had to be approved by the military governors. The military governors wanted to avoid the impression of dictating the German constitutional principles ; they also failed to give the Prime Minister a deadline to reply to the documents. Only the latest date for the meeting of the constituent assembly was set: September 1, 1948.

With Document No. II, the Prime Ministers were asked to review the national borders and, depending on the outcome, to make proposals to change them; Document No. III contained the points on which the military governors wanted to continue to determine. They should flow into an occupation statute, which should be put into effect at the same time as the constitutional law.

Koblenz resolutions

The days after the Frankfurt documents were handed over were characterized by great activity in the state governments and state parliaments . From July 8 to July 10, 1948, the West German heads of government met at the Knight's Fall in Koblenz in the French occupation zone. The invitation from the East German Prime Minister was no longer considered. In their "Koblenz Resolutions", the Prime Ministers declared the acceptance of the Frankfurt documents. At the same time, however, they turned against the creation of a West German state, as this would cement the division of Germany . The occupation statute was also rejected in its proposed form.

The military governors reacted angrily to the Koblenz resolutions because, in their opinion, they were presumptuous in attempting to override the London and Frankfurt documents. The French military governor Marie-Pierre Kœnig had secretly encouraged German politicians to object. In particular, the US military governor Lucius D. Clay blamed the prime ministers for the fact that the French were now calling for a revision of the London resolutions that would be detrimental to the Germans. In a further meeting on July 20, 1948, the Prime Minister was made aware of the negative consequences of insisting on the Koblenz resolutions. Although a constitution and not a provisional basic law was to be drawn up, the prime ministers finally agreed to the demands of the military governors.

At a prime ministerial conference at Niederwald Castle , the state leaders adhered to the Koblenz resolutions as a recommendation and to the designation “Basic Law” in order to emphasize its provisional character, despite their acceptance of the London resolutions . Furthermore, it was not a “constituent assembly”, but a parliamentary council , elected by the (West) German state parliaments and ratification of the Basic Law by the state parliaments and not - as the military governors wanted - decided by referendum. The reason for this was that German sovereignty had not yet been sufficiently restored and the prerequisites for an all-German constitution had also not been met. The military governors accepted this.

Constitutional Convention on Herrenchiemsee

The constitutional convention on Herrenchiemsee took place from August 10 to 23, 1948. It should consist more of administrators than politicians. Party political considerations should be left out. However, the state parliaments of the American and French occupation zones did not adhere to these recommendations. Although it was not clear whether the members of the Convention should provide a complete draft of a Basic Law or just an overview, important points emerged in the discussion, some of which were finally implemented in the Basic Law. These include a strong federal government , the introduction of a neutral head of state who, compared to the Weimar constitution, was essentially deprived of power, the extensive exclusion of referendums and a preliminary form of the later eternity clause . The design of the country representation was already controversial; it should remain so throughout the deliberations of the Parliamentary Council.

The groundbreaking preparatory work of the Convention had a considerable influence on the draft constitution of the Parliamentary Council. At the same time, the Herrenchiemsee Convention was the last major opportunity for the Prime Minister to influence the Basic Law.

Parliamentary Council

Work of the council

The Parliamentary Council drew up the new constitution on the basis of the principles of a federal and democratic constitutional state developed within two weeks by the Constitutional Convention. Principle of the members of the Parliamentary Council was the so-called "Constitution in short form", namely that Bonn is not Weimar was and the Constitution should receive a provisional time and space character. A constitution for Germany should only be defined as a constitution that was created and legitimized in the whole of Germany in a democratic way. Reunification was laid down in the preamble of the Basic Law as a constitutional goal (→ reunification requirement ) and regulated in Article 23 (which has since been repealed) . However, the vote on a constitution in accordance with Art. 146 that came into question in the event of reunification did not take place in view of the "accession of the German Democratic Republic to the scope of the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany". In the reason for not accepting a constitutional complaint (only marginally related to this question) , the Second Senate of the Federal Constitutional Court stated on October 12, 1993: “Article 146 of the Basic Law also does not establish an individual right which is subject to constitutional complaints (Article 93 (1) No. 4a of the Basic Law) . "

The members of this body (65 in total) were often referred to as the "fathers of the Basic Law"; Only later was it remembered that the four “ mothers of the Basic Law ”, Elisabeth Selbert , Friederike Nadig , Helene Wessel and Helene Weber were involved . Against fierce opposition, Elisabeth Selbert had enforced the equality of men and women ( Art. 3, Para. 2).

The members of the Parliamentary Council were elected by the West German state parliaments according to the proportion of the population and the strength of the state parliament groups. North Rhine-Westphalia sent 17, Bavaria 13, Lower Saxony nine, Hesse six, and the other states between five and one member. Of the 65 members, 27 belonged to the CDU or CSU and 27 others to the SPD , the FDP sent five members, the (national-conservative and federalist-oriented) German party , the (Catholic) center and the (communist) KPD two members each. The stalemate between the major parties prevented one of them from stamping the Basic Law and forced an agreement on the essential issues. The voting behavior of the smaller parliamentary groups was also decisive for the content and the acceptance of individual sections.

Approval and ratification of the Basic Law

After sometimes heated debates about the lessons to be learned from the failure of the Weimar Republic , the Third Reich and the Second World War , the draft of the Basic Law was approved on May 8, 1949 by the Parliamentary Council , which had been meeting in Bonn since September 1948, adopted with 53 votes to 12. The votes against came from members of the CSU, the German Party, the Center Party and the KPD. The anniversary of the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht was deliberately chosen as the date , which is why Adenauer forced the vote shortly before midnight. On May 12, 1949, the draft was approved by the military governors of the British, French and American occupation zones, albeit with a few reservations. According to Art. 144, Paragraph 1, the draft had to be adopted by the people's representatives in two thirds of the German states in which it was initially to apply. Between May 18th and 21st it was put to a vote in the state parliaments. A total of 10 state parliaments adopted the Basic Law.

Only the Bavarian state parliament voted in a session on the night of 19 to 20 May 1949 with 101 to 63 votes with nine abstentions against the Basic Law (seven of the 180 MPs were absent or excused). The proposal for rejection came from the state government . In contrast to the SPD and FDP, the CSU, which had a majority in the Bavarian state parliament, rejected the Basic Law. She feared too much influence from the federal government and called for a stronger federal character, for example equal rights for the Federal Council in legislation . The binding nature of the Basic Law for the Free State of Bavaria in the event that two thirds of the federal states would ratify the Basic Law was accepted in a separate resolution with 97 of 180 votes, 70 abstentions and six votes against.

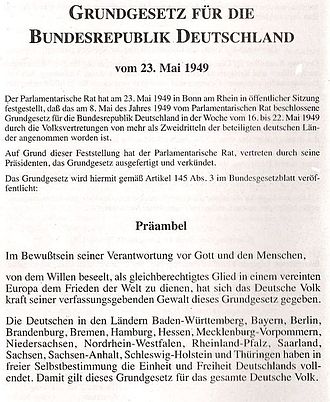

The Basic Law was drafted and promulgated on May 23, 1949 in a solemn session of the Parliamentary Council by the President and the Vice-Presidents ( Art. 145, Paragraph 1). The constitution was initially signed by 63 of the 65 voting members of the Parliamentary Council, i.e. by all but the two negative Communist MPs. Then the West Berlin deputies who were not entitled to vote , the prime ministers and state parliament presidents of the eleven West German states and finally Otto Suhr and Ernst Reuter as head of the city council and mayor of Greater Berlin signed .

“Today, May 23, 1949, a new chapter begins in the eventful history of our people: Today the Federal Republic of Germany will enter history. Anyone who has consciously experienced the years since 1933 thinks with a moved heart that the new Germany is emerging today. "

According to Art. 145 Paragraph 2, it came into force at the end of this day; the point in time is sometimes referred to as May 23, midnight, and others as May 24, 12 midnight. The Federal Republic of Germany was thus founded. This event is recorded in the initial formula .

The Basic Law was published in accordance with Art. 145 Paragraph 3 in Number 1 of the Federal Law Gazette. The original document ("original of the Basic Law") is kept in the Bundestag . The Basic Law also applied in and for Berlin ( West ), but only to the extent that measures by the occupying powers did not restrict its application. Their reservation made it impossible for federal bodies to exercise direct state power over Berlin.

On October 3, 2016, the first signed version of the Basic Law with all the accompanying files for a total of approx. 30,000 pages, including transcripts of the discussions and debates of the Parliamentary Council, the federal states, but also the Allied Powers, was microfilmed in the Central Recovery Site of the Federal Republic of Germany , the Barbarastollen , stored by the Federal Office for Civil Protection and Disaster Relief .

content

General

The Basic Law consists of the preamble , the standardization of fundamental rights (Articles 1–19) and the so-called rights equivalent to fundamental rights ( Article 20, Paragraph 4, Article 33 , Article 38 , Article 101 , Article 103 and Article 104 ) as well as the large complex of state organization law .

The division is made into articles instead of paragraphs .

These are a federal constitution , in addition to its existing state constitutions . The states have their own state quality and, despite belonging to the federal government , have in some cases considerable responsibilities, for example in civil service law , in the public service and in the school system.

Fundamental rights

In the section "Basic Rights" ( Art. 1 to Art. 19 ), the Basic Law specifies the rights that every person ( human rights or everyone's rights ) and especially every citizen (including civil rights or German rights ) has against those who exercise sovereignty . Also legal persons , as far as fundamental rights are applicable to them, carriers of fundamental rights. The basic rights of the Basic Law are essentially designed as the rights of the holder of the basic rights to defend themselves against actions by sovereign holders, but they also have a third-party effect on the legal relationship between persons. In this function, they give the holder of fundamental rights a claim against the state to have an impairment of the legal interest protected by the fundamental right in question removed. Under certain circumstances, other fundamental rights also lay claim to benefits from the state, be it through participation in existing state arrangements (participation rights, derivative performance rights, procedural rights) or the creation of new state arrangements (original performance rights).

The affected citizen can file a complaint about the constitutional complaint that the state must ensure that legal interests fall within the scope of protection of fundamental rights ( Art. 93 (1), 4a). Local self-government is also structured in a manner similar to that of fundamental rights ( Art. 28 Para. 2). The municipalities can also assert this right via the municipal constitutional complaint (Art. 93 Para. 1, 4b).

State organization law

Principles

The state organization law is divided into the list of general principles ( Art. 20 to Art. 29 , Art. 34 ), the internal organization law of the Federal Republic of Germany ( Art. 38 to Art. 69 ), which delimits the competences of the individual federal organs, and in the regulations on the relationship between the Federation and the Länder, which standardize the federal association's competence according to the principle of limited individual authorization ( Art. 30 to Art. 32 , Art. 35 to Art. 37 , Art. 70 ff.). Individual state organization law provisions can also be found in the section “Fundamental rights”.

In the section “The federal government and the states” the most important state principles are named: democracy, republic, welfare state, federal state (→ federalism ) as well as legality of state organs and separation of powers (→ rule of law ). The principles laid down in Article 1 ( human dignity ) and Article 20 , i.e. the core of the basic state order and fundamental rights, must not be changed in their essence by the power to amend the constitution ( Article 79, Paragraph 3; so-called eternity clause ).

Competencies of the federal bodies

The following sections define the competences of the individual federal state organs. As a constitutional bodies of the Federation of are German Bundestag , the Bundesrat , the Joint Committee , the Federal President , the Federal Assembly , the Federal Government , the Conciliation Committee and the Federal Constitutional Court listed.

The Bundestag and Bundesrat are called upon to legislate at the federal level. The Bundesrat is not an organ of the Länder, but a federal body in which representatives of the governments of the Länder sit. The representatives of the federal states have to cast their votes uniformly. Federal laws are passed by the Bundestag and forwarded to the Bundesrat immediately. For the further procedure, a distinction is made between objection laws and consent laws . In the case of objection laws, the Bundesrat can request the convening of the mediation committee, which consists of members of the Bundestag and Bundesrat who are not bound by instructions, within three weeks. If the mediation committee proposes a change, the Bundestag has to pass a resolution again. If the Federal Council agrees to the law or if it fails to submit an application to convene the mediation committee in due time, the law comes into force. If the mediation process has ended and the Bundestag has passed a new resolution in the event of a change in the legislative resolution by the mediation committee, the Bundesrat can lodge an objection within two weeks. If the objection is lodged by the Bundesrat in due time, the Bundestag can reject the objection. If the Federal Council waives an objection or if it withdraws it, the law has come into effect. In the case of consent laws , the procedure is different. Approval laws exist primarily for federal provisions on the establishment of state authorities and the administrative procedure for the implementation of federal laws as separate affairs of the states; in the case of federal laws in which the states have to bear a quarter of the expenditure or more; in the case of federal laws on taxes, the revenue of which goes partly to the federal states or the municipalities. If the Federal Council approves the law with a majority of its votes, it is passed. Otherwise the Federal Council can convene the mediation committee. In the case of consent laws, the Federal Government and the Bundestag can also demand that the Mediation Committee be convened. If the mediation committee makes a proposal to amend the legislative resolution, the Bundestag has to pass another resolution. The Federal Council can then refuse or allow this decision. If the mediation committee is not convened or if it does not make a proposal to amend the legislative resolution, the Federal Council must vote on the law within a reasonable period of time.

The federal government, together with the Bundestag, is responsible for state management and also for the implementation of certain federal laws by federal authorities . The Federal President is the head of state. He essentially performs representational tasks. The extent to which the Federal President has the authority to examine when drafting federal laws is controversial. It is often assumed that he has to check the correctness of the formation of laws (formal examination competence).

In its area of application, the Basic Law takes precedence over all laws and other national legal sources . The Federal Constitutional Court monitors compliance and interpretation . The constitutional judges decide v. a. about disputes between federal bodies, about disputes between states and the federal government. It examines the compatibility of state law and federal law, both in specific court proceedings and in the abstract at the request of the Bundestag, the federal government or a state government. It decides on constitutional complaints from citizens and societies as well as on complaints from municipalities regarding the violation of their municipal right to self-government.

The Joint Committee is the federal legislative body in the event of a defense .

Association competence of the federal government

The federal association's competence vis-à-vis the federal states follows the principle of limited individual authorization. In principle, the states are responsible for legislation and law enforcement, insofar as the Basic Law has not transferred responsibility to the federal government. In principle, the federal states also exercise jurisdiction, unless the federal government itself is the judge under the Basic Law. In case of doubt, they are therefore authorized to act sovereignly. The competence of the federal government is structured very differently in the areas of legislation, law enforcement and case law. In Art. 71 and Art. 73 are shown competence titles that authorize the federal government exclusively for the legislation. The Art. 72 , Art. 74 grant the federal government a preferential legislative power (from the Basic Law misleading competing legislation called); if the federal government does not make use of these rights, the states can legislate there.

Even with law enforcement, the federal government is only responsible on the basis of special authorization. The Art. 87 ff. Basic Law but have the federal government considerably less expertise in this area than in the area of legislation. The states therefore often implement federal laws as separate affairs. The federal government is the enforcement of federal laws by the states pertaining to legal supervisory authority. The Federal Council then has to determine such a violation of the law.

Essential differences to the Weimar constitution

The Basic Law, ratified in 1949, was a political reaction to the structural weaknesses of the Weimar Constitution of 1919, which had allowed democracy to be replaced by the Führer principle with the Enabling Act and conformity in the “Third Reich” .

In contrast to the Weimar Imperial Constitution, the basic rights under the Basic Law are not simply determinations of the objectives of the state , but directly applicable law for the state authorities committed to human dignity ( Article 1 ). The fundamental rights are at the beginning of the constitutional text and have a prominent importance both as subjective civil rights and in their function of an objective value decision of the state. Their essence must not be touched. The principle of Article 1, which defines this binding, must not be changed (eternity clause).

Parliament has a central role to play in safeguarding democracy. As the only constitutional body with direct democratic legitimacy, the Bundestag exercises significant influence on the composition of the other bodies. The primacy of legislative powers is expressed in several constitutional provisions. With regard to Weimar, the possibility of an emergency ordinance is excluded. Insofar as the government wishes to issue statutory provisions ( ordinances ), the content, purpose and extent must have been determined in advance in a parliamentary law ( Art. 80 ). Parliamentary laws can only be rejected by a decision of the Federal Constitutional Court ( Art. 100 ).

The head of state is no longer a “ substitute emperor ”, but with the exception of a few powers (such as the execution of laws and the associated right of examination or the federal pardon) limited to representation. In contrast to the Reich President , the Federal President is dependent on appropriate parliamentary majorities when appointing the head of government and dissolving the Bundestag. The position of the government vis-à-vis the head of state has been strengthened. The federal government is now only dependent on the Bundestag, instead of, like the Reich government under the Weimar Constitution, both on the Reich President and on the Reichstag. The federal government can only be overthrown by a constructive vote of no confidence , i.e. the election of a new chancellor. This ensures more stability than “in Weimar”, where right-wing and left-wing radicals could unite to vote out a chancellor without agreeing on a common candidate. In the Weimar Republic it was also possible to withdraw trust from individual ministers.

In some cases, the decisions of the Federal Constitutional Court have the force of law ( Section 31 (2 ) BVerfGG ). In practice, however, judgments are more likely to be formulated in such a way that the respective competent bodies have to change parts of a law complained about up to a more or less precisely measured period in accordance with the judgment. The Weimar Constitution did not provide for a court with such power. The amendment of the Basic Law, regulated in Art. 79 , is only possible under more stringent conditions than those applied to amendments to the Imperial Constitution. If the Basic Law is changed, the changed article must be specified explicitly. The Weimar Constitution could also be changed implicitly with every law that achieved a two-thirds majority . According to Article 79, Paragraph 3, the principles of Article 1 and Article 20 as well as elements of federal statehood may not be abolished (although federal states can be amalgamated , their general abolition is not possible). According to the separation of powers laid down in Article 20, for example, an “ enabling law ” such as that of 1933, which abolished the constitutional guarantees of fundamental rights, is not possible.

Parties are now protected by the party privilege in Art. 21 and can therefore only be prohibited by a decision of the Federal Constitutional Court. The Basic Law assigns them the task of forming the political will of the people , but requires that their internal order conforms to democratic principles .

Through the Bundesrat , the federal states are very much involved in the legislative process compared to the Reichsrat, given the large area of laws that require approval. The Reichsrat only had a suspensive veto right on legal issues. This involvement of the Federal Council is meanwhile subject to multiple criticism in the context of the federalism debate.

The Weimar Constitution contributed to the fact that the Reichswehr became a “state within the state”, also because it was subject to the Reich President, but not to parliamentary control. The Basic Law subordinates the Bundeswehr to the Defense Minister in the event of peace and to the Federal Chancellor in the event of defense .

Plebiscitary elements (such as plebiscites and referendums ) that entitle the people, as in the Weimar Republic, to introduce and pass laws, do not exist in the Basic Law at the federal level . Only in the case of a reorganization of the federal territory and in the case of the adoption of a constitution does the people decide directly. Since when the Federal Republic of Germany was founded, there was fear of misuse of these instruments by both communist and fascist forces in the still young and unstable democracy, the Parliamentary Council initially refrained from further elaboration. The expansion of direct democratic elements at a later point in time was never excluded by this, but only carried out by none of the subsequent federal governments.

Development of the Basic Law since 1949

overview

When the Parliamentary Council passed the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949 , the name “Basic Law” made clear the temporary nature of the constitutional text. The Basic Law should apply as a provisional arrangement until the division of Germany comes to an end. Then it was to be replaced by a constitution that the citizens of Germany would give themselves in free self-determination . In state practice, however, this usage of language by no means implies a provisional character, as the example of other constitutions, for example in the Scandinavian region or for the Netherlands , shows. The fact that the Basic Law “for”, not the Basic Law “of” the Federal Republic of Germany, is also a common use of the term.

In the 40 years of constitutional practice in the Federal Republic of Germany, the Basic Law has proven to be a successful model, so that the need to reconstitute the reunified Germany could by no means exceed the need for continuity, or a constitution that was freely adopted by the German people is not desired. Apart from a few minor changes, the Basic Law was retained in its tried and tested form. The Basic Law was changed by the Unification Treaty , for example in the preamble or Article 146.

The Basic Law has been amended around 60 times since it was issued on May 23, 1949. In 1949 it consisted of the preamble and 146 articles. By repealing articles (ex .: Art. 74a and 75 ), but also inserting new ones (ex .: Art. 53a , Art. 91d , Art. 120a GG,…) there were already 191 articles in 2010. There was no new publication, so the original count has been retained and the Basic Law still ends with Art. 146 . Art. 45d is the first and so far only article with an official title ("Parliamentary Control Committee").

The Basic Law underwent significant changes through the reintroduction of compulsory military service and the creation of the Bundeswehr in 1956, with which the so-called military constitution was implemented. Another major reform was the so-called emergency constitution (especially Art. 115a to Art. 115l ) passed in 1968 by the then grand coalition of CDU / CSU and SPD , which was politically very controversial. In 1969 the financial constitution was also reformed ( Art. 104a to Art. 115 ).

After German reunification, reform efforts came to a conclusion with marginal changes in 1994, which was sometimes perceived as disappointing (so-called constitutional reform 1994 ). However, as far as the parties have come to an agreement, the proven Basic Law should be adhered to as far as possible. A referendum on the Basic Law, which is valid for all of Germany (and is no longer provisional), was rejected by a majority, although this was called for with the argument that the Basic Law should be more firmly anchored, especially in East Germany . Also, the repeatedly requested inclusion of plebiscitary elements such as the people's legislation , which is now provided for in all state constitutions , did not take place .

A federal and state federalism commission , which in 2004 negotiated a new configuration of the legislative competences and the approval powers of the Federal Council, failed due to differences in education policy. After the formation of the grand coalition, the modified proposals for federalism reform entered parliamentary deliberations.

Further changes:

- In 1992 membership in the European Union was revised ( Art. 23 GG).

- In 1994 (and 2002) environmental and animal protection were included as state objective provisions in Article 20a of the Basic Law.

- The most politically controversial issues in 1993 were the restriction of the basic right to asylum and in 1998 the restriction of the inviolability of the home with the so-called large eavesdropping ( Article 13 Paragraphs 3 to 6 of the Basic Law, confirmed by the Federal Constitutional Court in 2004 as constitutional).

- In 2006 the federalism reform was passed with numerous changes to the legislative competence.

- In the course of the economic crisis in 2009 and the Federalism Reform II , the unbundling of the financial constitution was pushed further.

Amending laws

The constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany can only be changed by laws that meet the special requirements of Article 79 of the Basic Law; Constitutional laws are therefore always consenting laws. According to Article 79.2 of the Basic Law, a qualified majority of two thirds of the members of the Bundestag and two thirds of the votes of the Bundesrat is required. The high quorum makes constitutional changes much more difficult because weak or random majorities cannot make effective decisions. Certain constitutional principles and structural principles such as the direct binding effect of the fundamental rights , the federal structure or the democratic form of rule are expressly excluded from an amendment according to Article 79.3 of the Basic Law. The Basic Law is considered to be one of the most frequently amended constitutions in the world.

| No. | Changing law | Issued on | Federal Law Gazette | Changed articles | Type of Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Criminal Law Amendment Act | August 30, 1951 | Federal Law Gazette I pp. 739, 747 | 143 | canceled |

| 2 | Law to insert an Article 120a into the Basic Law | August 14, 1952 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 445 | 120a | inserted |

| 3 | Law amending Article 107 of the Basic Law | April 20, 1953 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 130 | 107 | changed |

| 4th | Supplementary Act | March 26, 1954 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 45 | 73, 79 | changed |

| 142a | inserted | ||||

| 5 | Second law amending Article 107 of the Basic Law | December 25, 1954 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 517 | 107 | changed |

| 6th | Financial Constitution Act | December 23, 1955 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 817 | 106, 107 | changed |

| 7th | Supplementary Act | March 19, 1956 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 111 | 1, 12, 36, 49, 60, 96, 137 | changed |

| 17a, 45a, 45b, 59a, 65a, 87a, 87b, 96a, 143 | inserted | ||||

| 8th | Law amending and supplementing Article 106 of the Basic Law | December 24, 1956 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1077 | 106 | changed |

| 9 | Law to insert Art. 135a into the Basic Law | October 22, 1957 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1745 | 135a | inserted |

| 10 | Supplementary Act | December 23, 1959 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 813 | 74 | changed |

| 87c | inserted | ||||

| 11 | Law to insert an article on air traffic administration into the Basic Law | February 6, 1961 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 65 | 87d | inserted |

| 12th | Twelfth law amending the Basic Law | March 6, 1961 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 141 | 96a | changed |

| 96 | changed | ||||

| 13th | Thirteenth law amending the Basic Law | June 16, 1965 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 513 | 74 | changed |

| 14th | Fourteenth law amending the Basic Law | July 30, 1965 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 649 | 120 | changed |

| 15th | Fifteenth law amending the Basic Law | June 8, 1967 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 581 | 109 | changed |

| 16 | Sixteenth law amending the Basic Law | June 18, 1968 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 657 | 92, 95, 96a, 99, 100; 96a turns 96 | changed |

| 96 aF | canceled | ||||

| 17th | Seventeenth law to supplement the Basic Law | June 24, 1968 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 709 | 9-12, 19, 20, 35, 73, 87a, 91 | changed |

| 12a, 53a, 80a, 115a-l | inserted | ||||

| 59a, 65a para. 2, 142a, 143 | canceled | ||||

| 18th | Eighteenth law amending the Basic Law (Articles 76 and 77) | 15th November 1968 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1177 | 76, 77 | changed |

| 19th | Nineteenth law amending the Basic Law | 29th January 1969 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 97 | 93, 94 | changed |

| 20th | Twentieth law amending the Basic Law | May 12, 1969 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 357 | 109, 110, 112-115 | changed |

| 21 | Twenty-first law amending the Basic Law (Financial Reform Act) | May 12, 1969 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 359 | 105-108, 115c, 115k | changed |

| 91a, 91b, 104a | inserted | ||||

| 22nd | Twenty-second law amending the Basic Law | May 12, 1969 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 363 | 74, 75, 96 | changed |

| 23 | Twenty-third law amending the Basic Law | 17th July 1969 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 817 | 76 | changed |

| 24 | Twenty-fourth law amending the Basic Law | July 28, 1969 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 985 | 120 | changed |

| 25th | Twenty-fifth law amending the Basic Law | 19th August 1969 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1241 | 29 | changed |

| 26th | Twenty-sixth law amending the Basic Law | 26th August 1969 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1357 | 96 | changed |

| 27 | Twenty-seventh law amending the Basic Law | July 31, 1970 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1161 | 38, 91a | changed |

| 28 | Twenty-eighth law amending the Basic Law | March 18, 1971 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 206 | 75, 98 | changed |

| 74a | inserted | ||||

| 29 | Twenty-ninth law amending the Basic Law | March 18, 1971 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 207 | 74 | changed |

| 30th | Thirtieth law amending the Basic Law | April 12, 1972 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 593 | 74 | changed |

| 31 | Thirty-first law amending the Basic Law | July 28, 1972 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1305 | 35, 73, 74, 87 | changed |

| 32 | Thirty-second law amending the Basic Law | 15th July 1975 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1901 | 45c | inserted |

| 33 | Thirty-third law amending the Basic Law | 23rd August 1976 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 2381 | 29, 39, 45a | changed |

| 45, 49 | canceled | ||||

| 34 | Thirty-fourth law amending the Basic Law | 23rd August 1976 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 2383 | 74 | changed |

| 35 | Thirty-fifth law amending the Basic Law | December 21, 1983 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1481 | 21 | changed |

| 36 | Unification Agreement | September 23, 1990 | Federal Law Gazette II pp. 885, 890 | Preamble, 51, 135a, 146 | changed |

| 143 | inserted | ||||

| 23 | canceled | ||||

| 37 | Amending law | July 14, 1992 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1254 | 87d | changed |

| 38 | Amending law | December 21, 1992 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 2086 | 24, 28, 50, 52, 88, 115e | changed |

| 23, 45 | inserted | ||||

| 39 | Law amending the Basic Law | June 28, 1993 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1002 | 16, 18 | changed |

| 16a | inserted | ||||

| 40 | Amending law | December 20, 1993 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 2089 | 173, 74, 80, 87 | changed |

| 87e, 106a, 143a | inserted | ||||

| 41 | Amending law | August 30, 1994 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 2245 | 73, 80, 87 | changed |

| 87f, 143b | inserted | ||||

| 42 | Amending law | October 27, 1994 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 3146 | 3, 28, 29, 72, 74-77, 80, 87, 93 | changed |

| 20a, 118a, 125a | inserted | ||||

| 43 | Amending law | November 3, 1995 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1492 | 106 | changed |

| 44 | Amending law | October 20, 1997 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 2470 | 28, 106 | changed |

| 45 | Amending law | March 26, 1998 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 610 | 13th | changed |

| 46 | Amending law | July 16, 1998 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1822 | 39 | changed |

| 47 | Amending law | November 29, 2000 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1633 | 16 | changed |

| 48 | Amending law | December 19, 2000 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1755 | 12a | changed |

| 49 | Law amending the Basic Law (Article 108) | November 26, 2001 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 3219 | 108 | changed |

| 50 | Law amending the Basic Law (state goal of animal welfare ) | July 26, 2002 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 2862 | 20a | changed |

| 51 | Law amending the Basic Law (Article 96) | July 26, 2002 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 2863 | 96 | changed |

| 52 | Law amending the Basic Law amendments |

August 28, 2006 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 2034 | 22, 23, 33, 52, 72, 73, 74, 84, 85, 87c, 91a, 91b, 93, 98, 104a, 105, 107, 109, 125a | changed |

| 104b, 125b, 125c, 143c | inserted | ||||

| 74a, 75 | canceled | ||||

| 53 | Law amending the Basic Law (Art. 23, 45 and 93) Changes |

October 8, 2008 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1926 | 45, 93 | changed |

| 23 para. 1a | inserted | ||||

| 54 | Law amending the Basic Law (Articles 106, 106 b, 107, 108) Amendments March 26, 2009 , July 1, 2009 |

March 19, 2009 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 606 | 106, 107, 108 | changed |

| 106b | inserted | ||||

| 55 | Law amending the Basic Law (Art. 45d) Changes |

July 17, 2009 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1977 | 45d | inserted |

| 56 | Law amending the Basic Law (Art. 87d) Changes |

July 29, 2009 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 2247 | 87d | changed |

| 57 | Law amending the Basic Law (Art. 91c, 91d, 104b, 109, 109a, 115, 143d) Changes |

July 29, 2009 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 2248 | 104b, 109, 115 | changed |

| 91c, 91d, 109a, 143d | inserted | ||||

| 58 | Law amending the Basic Law (Article 91e) amendments |

July 21, 2010 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 944 | 91e | inserted |

| 59 | Law amending the Basic Law (Article 93) amendments |

July 11, 2012 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1478 | 93 | changed |

| 60 | Law amending the Basic Law (Article 91b) amendments |

December 23, 2014 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 2438 | 91b | changed |

| 61 | Law amending the Basic Law (Article 21) amendments |

July 13, 2017 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 2346 | 21 | changed |

| 62 | Law amending the Basic Law (Articles 90, 91c, 104b, 104c, 107, 108, 109a, 114, 125c, 143d, 143e, 143f, 143g) amendments |

July 13, 2017 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 2347 | 90, 91c, 104b, 107, 108, 109a, 114, 125c, 143d | changed |

| 104c, 143e, 143f, 143g | inserted | ||||

| 63 | Law amending the Basic Law (Articles 104b, 104c, 104d, 125c, 143e) amendments |

March 28, 2019 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 404 | 104b, 104c, 125c, 143e | changed |

| 104d | inserted | ||||

| 64 | Law amending the Basic Law (Articles 72, 105 and 125b) amendments |

15th November 2019 | Federal Law Gazette I p. 1546 | 72, 105 and 125b | changed |

Validity period

According to Article 146 of the Basic Law, the Basic Law loses its validity on the day on which a constitution comes into force that has been freely decided by the German people . However, the Basic Law does not contain a call to adopt such a constitution. The original text of the preamble assigned the Basic Law to the task of "giving state life a new order for a transitional period" until 1990 . The preamble of the old version was concluded with the sentence "The entire German people are called upon to complete the unity and freedom of Germany in free self-determination."

In the reformulation as a result of the Unification Treaty of 1990, it has now been simplified and stated without restrictions that “the German people have given themselves this Basic Law by virtue of their constituent powers”. “The Germans in the federal states [list of federal states] have completed the unity and freedom of Germany through free self-determination. This Basic Law thus applies to the entire German people. "

In Article 146, the Unification Treaty added the subordinate clause “which will apply to the entire German people after the completion of the unity and freedom of Germany” to clarify that the article will continue to apply after the establishment of German unity.

The text passages of this Basic Law article are occasionally interpreted as meaning that only a directly - i.e. plebiscitary - adopted constitution fulfills the constitutional program of the Basic Law and the provisional status continues to exist. However, the majority in political science and law do not see this as a democratic deficit, because the principle of representative democracy , which is ultimately applied here, is not inadequate in terms of quality and democracy theory, but a gradual and systematic basic decision. The old version of the Basic Law also spoke of a free decision by the people - as a contrast to the political lack of freedom of the Germans in the GDR - but never of a direct decision. Therefore, special plebiscitary requirements cannot be derived from this. The German people always spoke freely and continuously through the constitution-amending legislature from 1990-94; it “found a valid, dignified and respected constitution in the Basic Law, under which it can lead a free, liberal, democratic life in a social and federal constitutional state”. Rather, Article 146, which was left in place, does not rule out a constitutional reform with the repeal of the Basic Law, but neither does it require it.

It is only apparently a contradiction that this all-German constitution continues to be called the “Basic Law”. The Basic Law not only fulfills all the functions of a constitution and has already established itself as such in the course of the history of the Federal Republic , but also meets the legitimacy requirements of a constitution. The retention of the original name Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany has historical reasons and can also be interpreted as respect for the work of the Parliamentary Council. At the moment, therefore, the statement on constitutional legislation is simplified: The Basic Law is the constitution.

Spatial scope

After the restoration of German unity, the Basic Law was changed:

- The preamble now states that the Basic Law applies to the entire German people, thus formally repealing the reunification requirement.

- The previous Art. 23 ( old version) , which kept the scope of the Basic Law open for “other parts of Germany”, has been dropped.

- Art. 146 makes it clear that Germany's unity is complete.

It follows that with Germany within the current borders the scope of the Basic Law has been finally determined and the Federal Republic of Germany does not have territorial claims .

Meaning and criticism

The Basic Law is an example of the successful re-democratization of a country. This applies in particular to the establishment of the Federal Constitutional Court , which has decisively shaped the interpretation and reality of the constitution with its case law . The Federal Constitutional Court with its far-reaching powers was unprecedented in 1949, as was the central importance of the principle of human dignity . In the meantime, both elements have been exported to other constitutions.

However, it is often pointed out that the development of a stable democracy in Germany can be traced back less to the concrete conception of the Basic Law and more to the economic prosperity of the post-war period. It is countered, however, that the economic strength of (West) Germany could not have developed without stable legal and political conditions. This includes in particular social peace, which was achieved through the welfare state law and the constitutional anchoring of trade unions and employers' associations ( Art. 9, Paragraph 3).

It is hardly disputed that the constitutional structure of the Basic Law based on the interlinking and control of powers has so far proven its worth. Often, however, federalism , i.e. the Federal Council's blocking options , is seen as an obstacle to the implementation of important reform projects. The Basic Law would de facto lead to a consensus democracy .

Participation in the formulation

See also

- List of articles of the Basic Law

- List of comments on the Basic Law

- Political system of Germany

- October Constitution

- International law clause

- Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union

- The setting of the Basic Law: right harmonious

- Artistic film adaptation of the Basic Law: GG 19 - Germany in 19 articles

literature

- 60 years of the Basic Law (= From Politics and Contemporary History 18-19). April 27, 2009 ( PDF ; 3.2 MiB).

- 70 years of the Basic Law as a special section in: Süddeutsche Zeitung , weekend edition from 4./5. May 2019, No. 103, pp. 45–62.

- Uwe Andersen, Wichard Woyke (Hrsg.): Concise dictionary of the political system of the Federal Republic of Germany. 5th, revised and updated edition, Leske + Budrich, Opladen 2003, ISBN 3-8100-3670-6 .

- Karl Dietrich Bracher : The German Basic Law as a Document of Historical-Political Experience. In: Hedwig Kopetz / Joseph Marko / Klaus Poier (eds.): Sociocultural change in the constitutional state. Phenomena of Political Transformation. Festschrift for Josef Mantl on his 65th birthday. Vol. 1. Böhlau Verlag, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2004, ISBN 3-205-77211-3 , pp. 759-779.

- Carl Creifelds (abbreviation): Legal dictionary. Edited by Klaus Weber , 17th edition, Beck, Munich 2002, keyword “Basic Law (GG)”, p. 623 f.

- Christian Bommarius : The Basic Law. A biography. Rowohlt, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-87134-563-0 .

- Joachim Detjen: The value system of the Basic Law. VS Verlag, Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-531-16733-6 .

- Christof Gramm, Stefan Ulrich Pieper: Basic Law: Citizens Comment. Nomos Verlag, Baden-Baden 2008, ISBN 978-3-8329-2978-7 .

- Peter Häberle : The Basic Law between constitutional law and constitutional politics. Selected studies on comparative constitutional theory in Europe. Nomos, Baden-Baden 1996, ISBN 3-7890-4005-3 .

- Peter Häberle: The Basic Law of the Letters. The constitutional state in the (distorting) mirror of beautiful literature. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 1983, ISBN 3-7890-0886-9 .

- Konrad Hesse : Fundamentals of the constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany , 20th edition, CF Müller Verlag, Heidelberg 1999, ISBN 3-8114-7499-5 .

- Axel Hopfauf: Introduction to the Basic Law. In: Hans Hofmann / Axel Hopfauf (ed.): Commentary on the Basic Law. 12th edition, Carl Heymanns Verlag, Cologne 2011, ISBN 978-3-452-27076-4 .

- Hans D. Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany. Comment. 11th edition, Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-60941-1 .

- Albert Krölls : The Basic Law - a reason to celebrate? A polemic against constitutional patriotism. VSA, Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-89965-342-7 .

- Peter Schade: Basic Law with commentary. 8th edition, Walhalla-Fachverlag, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-8029-7176-1 .

- Maximilian Steinbeis , Marion Detjen, Stephan Detjen : The Germans and the Basic Law. History and Limits of the Constitution. Pantheon, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-570-55084-7 .

- Klaus Stern : The Basic Law in a European Constitutional Comparison. Lecture given to the Berlin Legal Society on May 26, 1999 , de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2000, ISBN 3-11-016824-3 .

- Jochen Roose: The living constitution. Fundamental rights from the point of view of the population: value, implementation, limits. Konrad Adenauer Foundation , Berlin 2019 ( PDF; 1.6 MB ).

Web links

Different versions of the Basic Law

- Text of the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany in the current version, website of the Federal Ministry of Justice / juris

- The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany , Federal Law Gazette 1949 No. 1 p. 1, issued in Bonn on May 23, 1949. With an introduction by Udo Wengst

- Federal government (REGIERUNGonline): All-German constitution: Basic law for the Federal Republic of Germany

- Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany of May 23, 1949. Historical-synoptic edition. 1949–2009 - all versions since the entry into force with period of validity and synopsis (lexetius.com)

- Discover our constitution! , Open Data Movement (with timeline of changes to the Basic Law in connection with important events in German history)

- The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany , can be ordered from the Federal Agency for Civic Education and a link to download (Basic Law in Turkish and Arabic)

- German Bundestag (undated): Basic Law amendments (with information on the formal and substantive changes to the Basic Law and references to statistics on Basic Law amendments, Basic Law amending laws, amended Basic Law articles, unapproved draft amendments and joint bodies or commissions of the Bundestag and Bundesrat to reform the Basic Law; last accessed: April 19, 2018)

Historical speeches on the Basic Law

- Carlo Schmid at the second session of the Parliamentary Council on September 8, 1948. In: The Parliamentary Council 1948–1949, Files and Minutes, Volume 9: Plenary , edited by Wolfram Weber. Munich 1996, pp. 20 - 45 , spd.de (PDF) . Audio recording on YouTube (1 h 57 min)

- Navid Kermani : Speech by Dr. Navid Kermani at the ceremony "65 years of the Basic Law" ( Memento from May 27, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), May 23, 2014

Explanations on the Basic Law (selection)

- Horst Dreier : The Basic Law - a constitution on demand? , in: From Politics and Contemporary History No. 18/2009 of April 27, 2009

- Hauke Möller : The people's constituent power and the barriers to constitutional revision: An investigation into Article 79 Paragraph 3 of the Basic Law and the constituent power according to the Basic Law. dissertation.de, Berlin 2004 (also: Universität Hamburg, Diss., 2004, PDF; 831 KiB)

- Basic Law in the information portal on political education

- Hans Vorländer : Why Germany's constitution is called the Basic Law , September 1, 2008

- Knut Ipsen : Basic Law - Constitution / Constitutional Reform , in: Concise Dictionary of the Political System of the Federal Republic of Germany , 2013, website of the Federal Agency for Civic Education

- Basic Law and Parliamentary Council , dossier on the website of the Federal Agency for Civic Education (images provided by the House of History )

- Central Council of Muslims in Germany , Muhammad Sameer Murtaza : The Basic Law in (Migrations) -Vordergrund , islam.de, accessed on June 28, 2017. Explanation for a target audience with a migrant, especially Muslim background.

Remarks

- ↑ Art. 145, Paragraph 2: “This Basic Law comes into force at the end of the day of its promulgation.” See also section “ Approval and ratification of the Basic Law ”.

- ↑ BVerfG, 2 BvE 2/08 of June 30, 2009, paragraph no. 218 ; cf. the designation of the Basic Law as a “German constitution” in 2 BvR 1481/04 of October 14, 2004, paragraph nos. 33, 35 or “our federal constitution” in BVerfGE 16, 64 (79) .

- ^ Paul Kirchhof , Charlotte Kreuter-Kirchhof: Constitutional and administrative law of the Federal Republic of Germany. With European law. 51st, revised and expanded edition, CF Müller, Heidelberg 2012, accompanying word.

- ↑ a b Maunz / Dürig-Scholz, Commentary on the Basic Law , Art. 23, Rn. 71 ff.

- ↑ See Lüth judgment .

- ↑ BVerfG, judgment of the First Senate of January 15, 1958 - 1 BvR 400/51 - BVerfGE 7, 198 - Lüth, 1st principle.

- ↑ See Wiktionary: perpetuate .

- ↑ Klaus Stern , The State Law of the Federal Republic of Germany - Volume V , CH Beck, Munich 2000, p. 1969, 1973 .

- ↑ Cf. Manfred G. Schmidt , The political system of the Federal Republic of Germany , CH Beck, Munich 2011, chap. 1 .

- ↑ Gerhard Köbler : German Etymological Legal Dictionary , p. 170 ( PDF; 195 kB ); Entry Basic Law. In: Jacob Grimm , Wilhelm Grimm (Hrsg.): German dictionary . tape 9 : Greander gymnastics - (IV, 1st section, part 6). S. Hirzel, Leipzig 1935 ( woerterbuchnetz.de ).

- ↑ Cf. Christian Starck , Where does the law come from? , Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2015, pp. 78 , 132; Josef Isensee , On the style of the constitution. A typological study of the language, subject matter and meaning of the constitutional law. Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen / Wiesbaden 1999, p. 39 f.

- ↑ For details, see Axel Hopfauf, in: Schmidt-Bleibtreu / Hofmann / Hopfauf, Commentary on the Basic Law , 12th edition 2011, introduction, marginal number 18.

- ↑ For details see Hopfauf, in: Schmidt-Bleibtreu / Hofmann / Hopfauf, Commentary on the Basic Law , 12th edition 2011, introduction, marginal number 19.

- ↑ Hopfauf, in: Schmidt-Bleibtreu / Hofmann / Hopfauf, Commentary on the Basic Law , 12th edition 2011, introduction, margin no. 20.

- ↑ For details, see Hopfauf, in: Schmidt-Bleibtreu / Hofmann / Hopfauf, Commentary on the Basic Law , 12th edition 2011, introduction, paras. 19-21.

- ↑ See also the report on the Constitutional Convention on Herrenchiemsee, in: German Bundestag and Federal Archives (ed.): The Parliamentary Council 1948–1949. Files and protocols , Vol. II: The Constitutional Convention on Herrenchiemsee , Boppard am Rhein 1981, ISBN 3-7646-1671-7 , p. 507.

- ↑ The current version contains norms on the relationship with the EU .

- ↑ For the common designation "Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany" instead of "for" see the announcement of the letter of the President of the People's Chamber of the German Democratic Republic of August 25, 1990 and the decision of the People's Chamber of August 23, 1990 on the accession of the German Democratic Republic on the area of application of the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany (B. of September 19, 1990, Federal Law Gazette I, p. 2057 ; effective from September 28, 1990)

- ↑ BVerfGE 89, 155 (180) - Maastricht

- ↑ Hopfauf, in: Schmidt-Bleibtreu / Hofmann / Hopfauf, Commentary on the Basic Law , 12th edition 2011, introduction, margin no. 22.

- ↑ For details see Hopfauf, in: Schmidt-Bleibtreu / Hofmann / Hopfauf, Commentary on the Basic Law , 12th edition 2011, introduction, marginal 37.

- ↑ Five minutes past twelve . In: Der Spiegel . No. 20 , 1949 ( online ).

- ↑ Letter of approval from the military governors of the British, French and American occupation zones on the Basic Law of May 12, 1949 ( Memento of February 22, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), on: verfassungen.de

- ↑ Why Bavaria rejected the Basic Law , Deutschlandfunk , contribution from May 20, 1999.

- ↑ Bavarian State Parliament: 110th session on May 19 and 20, 1949 (shorthand report; PDF; 15.1 MB)

- ↑ Observations - The Parliamentary Council 1948/49: Signature , Foundation House of the History of the Federal Republic of Germany , accessed on April 22, 2018.

- ↑ Otto Langels: The Parliamentary Council announced the Basic Law. In: Calendar sheet (broadcast on DLF ). May 23, 2019, accessed May 23, 2019 .

-

↑ Othmar Jauernig , When did the Basic Law come into force? , JuristenZeitung 1989, p. 615;

Peter Michael Huber , in: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law - Commentary , CH Beck, Art. 145 Rn. 5;

Dieter C. Umbach, in: ders./Thomas Clemens (Ed.): Basic Law. Employee commentary and manual , Volume II, Heidelberg 2002, Art. 145 Rn. 23 ff. -

↑ Ingo von Münch , Die Zeit im Recht , NJW 2000, p. 1 ff., Here p. 3.

Cf. but also Ingo von Münch / Ute Mager , Staatsrecht I. Staatsorganisationsrecht taking into account the references to European law , 7., completely revised Edition 2009, Rn. 36, Note 16 : “The question of whether the Basic Law came into force on May 23rd at midnight [...] or on May 24th at midnight [...] is st. [controversial], but of no practical importance. " - ^ German Bundestag - Basic Law

- ↑ Cf. Jutta Limbach , Roman Herzog , Dieter Grimm : The German Constitution: Reproduction of the originals from 1849, 1871, 1919 and the Basic Law from 1949 , ed. and introduced by Jutta Limbach, CH Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-44884-4 , p. 252 .

- ↑ The German Basic Law on microfilm. 500 years secured for posterity. Federal Office for Civil Protection and Disaster Assistance, accessed on October 4, 2016 .

- ↑ For other constitutions, see the list of basic laws , and for simple laws such as the Water Act for Baden-Württemberg, etc .; but also the preamble to the old version of the Basic Law (sentence 1, last half-sentence): "[...] this Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany adopted by virtue of its constituent power ."

- ↑ Ursula Münch : 1990: Basic Law or New Constitution? (October 1, 2018, first published on September 1, 2008), Federal Agency for Civic Education / bpb.

- ↑ 60 Years of the Basic Law - Facts and Figures Scientific Services of the German Bundestag , 2009 (evaluation from 144/09).

- ↑ Changes to the Basic Law since 1949 - content, date, voting results and text comparison (PDF; 1 MB), Scientific Services of the German Bundestag. Completion of work: November 18, 2009 (updated version from 144/09).

- ↑ U. a. Art. 12a, 17a, 45a – c, 65a, 87a – c.

- ↑ Cf. Kunig, in: v. Münch , Basic Law Commentary, Preamble, Rn. 34 f.

- ↑ Now regulated in Art. 16a GG.

- ↑ 1996 confirmed as constitutional by the BVerfG.

- ↑ Christoph Degenhart , Staatsrecht I, Staatsorganisationsrecht , 30th edition, 2014, Rn. 242 .

- ^ Thomas Ellwein : Constitution and Administration. In: Martin Broszat (Ed.): Caesuras after 1945. Essays on the periodization of German post-war history (= series of the quarterly books for contemporary history , vol. 61). Oldenbourg, Munich 1990, ISBN 978-3-486-70319-1 , p. 47 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ a b Synopsis Preamble GG, lexetius.com

- ↑ It is controversial whether the spelling “constitutional” is grammatically correct. In the opinion of many, it should correctly read “constitutional” (without a so-called fugue-s ), which is also supported by the advice center of the Duden editorial team. The Society for German Language, however, considers both spellings to be justifiable, which is why a petition calling for the spelling to be changed was rejected. Response of the Petitions Committee to a petition directed against the removal of the joint ; see also Spiegel Online: Bundestag must correct decades-old grammatical errors in the Basic Law ; Message dated October 2, 2004.

- ↑ Quoted from Klaus Stern, Staatsrecht , Vol. V, 2000, p. 1973.

- ↑ Regarding Art. 146 GG new version, see Stern, Staatsrecht V , § 135 III 8 Abs. Γγ (p. 1971): “[...] In political practice, after almost a decade of validity, the provision has been reduced to an authorization with no follow-up effect. Despite extensive scientific treatment in the commentary literature , because of its 'irritation volume' it is viewed as an ultimately functionless norm over which development has progressed. [...] It is better to paint them. "

- ↑ "The Basic Law is thus the legitimized constitution of reunified Germany ." Quoted from Klaus Stern, Das Staatsrecht der Bundesoline Republik Deutschland - Volume V , CH Beck, Munich 2000, p. 1969 . See also ibid., § 135 III 8 section β (pp. 1971–1973 mzN) on the alleged legitimation deficit (with further evidence) that the so-called birth defect theory has (in the meantime) become untenable, as well as that the accusation that the Basic Law is liable the taint lack referendum on, "[o] n constitutional legal arguments [...] are not supported [could]: [... the] provisional ( 'provisional') [...] was [...] just with reunification on 3 October 1990 unequivocally their end. This remedied this only deficit with regard to a full constitution. [... The Basic Law] could and wanted to become the constituent permanent order according to its own understanding [...]. In the event of accession, however, a referendum was not planned. ”The Joint Constitutional Commission set up by the first all-German Bundestag and Bundesrat refrained from either a new constitution or a total revision or a referendum in 1994.

- ↑ More on this Knut Ipsen in: Ulrich Beyerlin et al. (Ed.): Law between upheaval and preservation. Festschrift for Rudolf Bernhardt (= contributions to foreign public law and international law , vol. 120). Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg / New York 1995, p. 1043 f. , Chap. I.1 (“Constitutional limitation of the territorial scope of application”).

- ↑ See also: Dieter Gosewinkel : Copyright: Basic Law. In: Zeit Online . May 25, 2019. Retrieved May 26, 2019 .