Jesuit reduction

As a Jesuit Reduction one of those is Jesuits built settlement for the indigenous population in South America called. Jesuit reductions were a Jesuit missionary work in the period from 1609 to 1767. Hundreds of thousands of members of the indigenous population of South America were brought together in permanent settlements, the reductions (Spanish : reducción , "settlement, settlement"). The Jesuit reductions were often referred to as Jesuit states because they were largely independent of Spanish authorities .

background

The discovery of America at the end of the 15th and beginning of the 16th centuries by the then European great powers Spain ( Juan Díaz de Solís ) and Portugal and the subsequent, gradually cruel conquest (called the Conquista of Latin America ) opened up enormous amounts of new raw material deposits. From the beginning it was intended to subdue the natives by means of the encomienda system in order to be able to exploit the immense mineral resources (especially gold and silver deposits) of the new world .

Because the great power Spain saw itself as a propagator of Christianity on behalf of God, it believed it was entitled to conquer . The conquerors, however, sought riches, souls that could not be converted. The natives were seen less as people than as workers. In contrast, the Dominican and Bishop Bartolomé de Las Casas treated them humanely at the beginning of the 16th century. The Franciscan Luis de Bolaños came to Asunción in 1575 and developed the idea of «reducciones» for the locals to protect them from exploitation.

At a time when slavery was widespread, the invading European entrepreneurs also tried to forcefully recruit indigenous workers. Many locals who resisted were killed. In the 17th century z. B. in the province of Santiago del Estero 80,000 locals, in 1750 there were only 80; 40,000 in the province of Córdoba, 40,000 in 1750. At the same time, the Portuguese and Spanish colonialists endeavored to spread European culture and Christianity .

The Roman Catholic Church had taken the first missionary steps in direct connection with the conquest campaigns of the conquistadors . Already in the period from 1547 to 1582 dioceses were established in Paraguay , Tucumán and Buenos Aires . The earliest preachers of the faith in the subcontinent were traveling preachers as entourage or vanguard of the conquering army units. Their effect was moderate, as the new beliefs mixed with paganism . This missionary work in connection with the violent conquest mostly met with negative and often hostile reactions from the natives, who were now to lose not only their socio-political , economic and cultural independence, but also their religious beliefs.

From these experiences, some colonialists tried to spread the Christian faith in a new way. This was followed by preliminary forms for the later reductions. This already existed in the early days of the colonization of America as a means of better exploiting the Indian labor force in the Antilles . There the reductions were first used in today's Guatemala by Franciscans , Mercedarians , Capuchins , Dominicans and Hieronymites as an instrument of preaching the faith.

State and Church

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the state and the Roman Catholic Church in Portugal and Spain were linked. The respective monarchy determined who was admitted as missionary , the authorities determined the mission method, appointed bishops and church organizations . The missionary penetration of South America could only succeed with the military protection and the material support of the crown. The structural alliance of state, church and missionary organization created serious tensions.

Holy experiment

Shortly after the founding of the Society of Jesus by Ignatius of Loyola (1540), Portugal's King Joâo III asked him to send some priests to the American possessions of the Portuguese crown. This is because the Jesuits attached particular importance to adaptability ("accommodation") and cultural exchange in their missions to spread the faith in order to best meet the human needs of the locals and their dignity . The first Jesuits then set foot on American soil in 1549, but no more than the first missionaries. They were promised to be of great help in promoting peace in order to improve the conversion and education of the local people.

A synod held in 1603 advocated measures against the exploitation of the natives by separating them from Spaniards in order to achieve successful proselytizing. This gave the Jesuits the right to use their reduction system within the Spanish colonial area. This venture was soon admired and later mockingly referred to as the “Holy Experiment”.

After the Jesuits initially only worked among the colonists of South America, from 1576 they took part in the mission among the natives. This began first at Lake Titicaca in the south of Peru , where ideas and models for the Indian mission were developed in order to win over the indigenous population in the lowlands, which are difficult to access, for the gospel . The first experiences were groundbreaking for the integrative missionary work in other parts of the continent, such as in Ecuador , Bolivia and especially from 1588 in Paraguay with the local Guaraní .

The efforts of the Jesuits focused on avoiding the difficulties of the encomienda system such as oppression of the locals with violence, with consequent abhorrence of the religion of the oppressors and their example. The spirit of the reductions therefore corresponded to an anti-colonial experiment and was ultimately not compatible with the goals of the colonial powers - indeed, diametrically opposed to them. This project of the Jesuits, which was initiated by the Spanish King Felipe III. was powerfully supported, provoked a wave of hostility from the colonists. On the other hand, the king issued a number of decrees and allowed financial contributions from the state treasury to legally regulate the problem of the oppression of the natives .

Training centers and first reductions

In addition to the establishment of schools, colleges , high schools and retreats in many areas (e.g. in Santiago del Estero , Asunción , Córdoba (has had a university since 1621), Buenos Aires, Corrientes , Tarija , Salta , San Miguel de Tucumán , Santa Fe , La Rioja ), reductions were also created to protect the locals. The 5th general of the Jesuits, Claudio Acquaviva , insisted on the creation of centers in the most attractive places. This was implemented by the first head of the province of Paraguay, which was founded in 1606, Diego de Torres Bollo , according to a newly decided uniform model of missionary work, so that six years later - after initially only seven - 113 priests were on duty here.

According to a royal cédula real of January 30, 1607, it was forbidden in future to use locals baptized as Christians as serfs . Unbaptized natives were only viewed as inferior "savages". The royal Cédula Magna of March 6, 1609 stipulated even further: "The Indians should be as free as the Spaniards".

With the term “reduction” the basis for a humane, successful missionary work and proclamation of faith was proven: The gathering of the nomadically scattered and self-sufficient natives, who have hitherto been hunters and gatherers , at best occasionally also farming , in common settlements to settle down.

The first reductions were set up in what was then the province of Guayra (today the state of Paraná in Brazil ): in 1609 in Loreto del Pirapó on the Paranapanema river , followed in 1611 by another in San Ignacio Miní . By 1630, another eleven settlements with 10,000 converted to Christianity locals had been built. The Jesuits succeeded in all of this not least because the locals were continually hunted by slave hunters and looters. Large numbers of them fled to the reductions, where they found safe shelter . The territory of the reductions was directly under the jurisdiction of the Crown.

Build up further reductions

As the reductions proved their worth, more were gradually built, so that in the end there were around 100 settlements. The number of residents varied considerably as epidemics raged again and again , which the locals often succumbed to due to a lack of physical resistance .

With the Guaraní in the area of today's Paraguay as well as in today's Argentine provinces Misiones and Corrientes and in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul, 30 Guaraní reductions were created , with a maximum of 140,000 inhabitants in 1732. In the period from 1610 to 1768, over 700,000 locals were baptized as Christians there. In the Chiquitos area in the east of today's Bolivia, 10 Chiquitos reductions were built between 1696 and 1790, with 23,288 residents (4,981 families) in 1765. In the three reductions of the Taruma (between the Guaraní and the Chiquitos in San Joaquin, San Estanislao and Belen) in 1766 3,777 people lived in 803 families. Between 1645 and 1712 there were also reduction-like Jesuit missions in the Amazon in the border area between Peru and Brazil with the Omagua with more than 30 villages, which were last looked after by the Bohemian missionary Samuel Fritz , who had been with the Indians since 1685 as a “medicine man”. With eleven different Indian tribes in the Gran Chaco , fifteen reductions were founded between 1735 and 1767 with over 17,000 inhabitants, of which 5,000 were Christianized. Further reductions were made among the Chiriguanos and Mataguayos in Tucumán and Northern Patagonia (Terra Magallonica) , such as B. Nuestra Señora del Pilar .

Defense of the reductions

The competition felt as a result of the success of the reductions sparked increasing hostility from the conquistadors, civilian traders and entrepreneurs (such as António Raposo Tavares ). Their displeasure resulted in harassment and recurring attacks on the Jesuit reductions. Around 1630 entire villages were attacked and burned down, tens of thousands of locals were either put into slave service or murdered. In vain did the Jesuits seek protection from the Spanish and Portuguese authorities; they didn't want to or couldn't help. Because of these cruel experiences, King Philip IV gave the Jesuits permission to set up an armed militia to defend the reductions. In this way, a well-disciplined Indian army armed with firearms emerged by 1640. This measure was to prove itself in a further attack by the gang members (also called Paulistas ) in 1641 in a defensive battle.

The main strength of the reduction defense was its cavalry . This was often used by the king or governor to defend himself against Paulistas or in disputes with the Portuguese and the English who threatened Buenos Aires. From 1637 to 1735 the defense services of the reductions were also used by the king over 50 times, often with many victims and losses among the locals.

Creation of reductions

The village communities, which were mostly laid out on a hill next to a river, offered between 350 and 7,000 and more locals a common, safe home. The fields for the cultivation of grain, sugar cane, cotton, mate, etc. expanded in a wide area. Handicraft businesses such as B. a brickworks, grain mill, tannery or a stamping mill, etc. Each reduction also had an estancia ( farm ) for the production of vegetable or animal products - often located far away . These courtyards were surrounded by protective ditches or walls, pole or thorn fences, depending on the risk. The first American wine for export was also grown in the Estancia of Jesús María .

The focus of every reduction was the impressive, three-aisled church with a bell tower , carefully and artistically equipped with a crucifix and a statue of the Virgin Mary , shaded by trees. This was flanked on the one hand by the house of the fathers with the school and on the other hand by the cemetery with a pillared hall with a chapel for the dead. The people's house with the storage facilities and the workshops was located next to the fathers' accommodation . There was also a widow's house ( gotiguazu ) and a hospital. Around the imposing church square, the single-storey residential houses of the locals, solidly built from adobe bricks or stones, were arranged in rows . The roofs were all covered with tiles for fire protection reasons. The 4 to 6 living rooms per house for families with 4 to 6 people were approx. 4.5 by 6 meters in size and divided by woven partition walls. A colonnade was attached to the front and back of the houses so that everyone could move around the settlement even when it rained. The roads were often paved too. There was a visitor house on the edge of the village.

In order to enable communication and traffic between the individual reductions, efficient roads and paths were created, often over large distances. The existing waterways were also used: the missionaries had no fewer than 2000 smaller and larger boats in use on the Río Paraná alone , as were about as many on the Río Uruguay with its ports such as z. B. Yapeyu .

Internal organization

As a rule, two Jesuits led a reduction, with one officially representing the Spanish king by law. The Jesuits organized and directed the whole business. They not only worked as pastors, but also as organizers, councilors, judges, doctors, architects, musicians, church and instrument makers, craftsmen, merchants, engineers, etc.

White settlers and mestizos , including government representatives or the bishop, officially had no access to the reductions. The indigenous men could be appointed by their caciques , the traditional clan heads, to a municipal administration based on the Spanish model. Within the reductions there was no money and no private ownership of the means of production.

The missionaries were financially supported by the home state to set up the first reduction; however, successful efforts were made to make the settlements economically independent. In addition, the locals, who were not used to regular work, had to be encouraged to do their daily work. Without the work they would have remained on the level of semi-nomads and thus exposed to the hostility of the Paulists . Thanks to the know-how of the Jesuits and the organized cooperation, the reductions developed into prosperous economic centers.

The land (fields for the locals and the community), the buildings, the cattle herds and all facilities for the reduction were basically the property of the whole village community. Through the fathers, the cultivable agricultural area for the locals was divided up into the caciques, who assigned it to the individual families. The field yields achieved with their own efforts were the unrestricted property of these families, which they could also use for internal bartering. The farm equipment and grazing cattle were borrowed from the community. Nobody was allowed to sell their property or house (called abamba, i.e. own property). These family fields were occasionally swapped with one another. The yields from the community fields were stored in the community stores. Some of these were also used for the poor, sick, widows and orphans , church servants, etc., also as seeds or for barter for other products.

In addition to their household chores, the women were required to help meet the needs of the community with harvesting cotton, spinning yarn, tailoring clothes, and the like. In some reductions, the self-picked cotton could be handed in to a separate spinning mill. The men, who were not assigned a special task, were obliged to work two days a week in community work in the fields or in public buildings. Everyone had to work during the harvest. Playing cards and dice was not allowed. Although the locals were more or less capable of the various tasks, no classes or groups of people were formed among them who could exercise power.

Activities in the reductions

Everyday life - prayer, work and free time - was strictly regulated and was indicated by the chimes of bells. Work (8-hour day), school and food had their time as well as entertainment and dancing. On non-working Sundays and public holidays, church services were celebrated lavishly with music and singing. Boys and girls sat separately in church and received religious instruction every day. Church music was carefully cultivated and the local choirs were often invited to visit Spanish cities. The school teachers were local people trained by fathers. The pupils were mainly children of caciques and other important natives who were trained in reading, writing and arithmetic. In this regard, the reductions were better organized than the Spanish colonies, which aroused envy among colonialists.

The food was prepared by the families. To do this, they needed the produce of their fields, supplemented with other food from the communal stores. In addition, the locals were regularly given the much sought-after meat from the communal slaughterhouses. In order to prevent the locals from devouring the ration of meat in a single day, they were made to make part of the meat into charqui . H. drying it in the sun and then pulverizing it. Special meals prepared in the rectory were given to the sick. The children received morning and evening meals together in the forecourt of the rectory.

Twice a year, each family received the necessary amount of wool and cotton from which the women sewed new clothes. Except for the priests, all the residents of the reductions were dressed in the same way; only the caciques were slightly different. Better quality fabrics such as B. for the altar decorations, had to be imported. Boys married when they were 17, girls when they were 15. The families had an average of 4 children.

Nursing was well organized. Each reduction had up to eight well-trained nurses ( curu zuya ) who reported to the fathers daily. Medicines were generally prepared from local medicinal herbs . But there was also a pharmacy and medical books. Several fathers and lay brothers were medically trained. The Innsbruck- born Jesuit Sigismund Aperger (1678 to 1772) was particularly famous in this regard .

Products of reductions

Each reduction looked for its own path to economic success and focused on certain products. They exchanged these with one another as required and also passed on their knowledge and experience. The Fathers dedicated themselves to agriculture with particular commitment.

The locals were able to satisfy their own needs with the cultivation of cassava ( yuca ), various tubers for food and with a little cotton. The reductions also expanded their capacities for other products and soon surpassed the yields of the Spanish settlements, also in terms of profitability and diversity. In addition to the production of meat and leather, the usual field products such as wheat and rice, etc., tobacco, indigo , sugar cane and especially cotton were cultivated. Various fruits have also been grown with success. Even today, in the wilderness, one can find signs of the great orchards of reductions, especially of orange groves . With viticulture had less success.

One of the most successful export products was the so-called Paraguay tea herba ( mate leaves cut into small pieces, dried). This tea was also the most popular drink in the reductions and thus replaced the intoxicating drinks of the mostly alcohol-dependent locals. After the reductions succeeded in planting this tea in their settlements, this aroused envy among the colonialists. They suppressed this success by all means.

Other natural products such as tropical woods, honey, beeswax, aromatic resins, etc. have been reworked for meaningful use. Attempts were even made to extract pig iron with little effort. A great, lucrative development was achieved with cattle and sheep breeding on the extensive grassy areas of these countries. Some reduction farms had up to 30,000 sheep and over 100,000 cattle. Such numbers exceeded those of the Spanish haciendas . The herds of cattle were periodically enlarged and their breeding improved through the careful selection and breeding of wild cattle. Horses, mules, donkeys and poultry were also raised on a large scale. Fishing and hunting also contributed to the maintenance.

Development of branches of industry

Since the import of goods from overseas was difficult and expensive and there was a great demand for necessary goods, the reduction of the Guaranís in particular began with the training of specialists for sought-after branches of industry. These locals were suitable for almost all manual work. They became master builders, carpenters, bricklayers, brick makers, picture carvers, house painters, painters, joiners, turners, sculptors, stone carvers, iron or goldsmiths, pewter and bell foundries, potters, gilders, instrument and organ builders, arms mechanics, bookbinders and weavers , Dyers, tailors, bakers, butchers, tanners, shoemakers, copiers, calligrapher, cattle breeders, beekeepers etc. Still others were employed in mills for the production of powder, tea or cornmeal. Each branch of the profession had its superior who was in constant contact with the fathers.

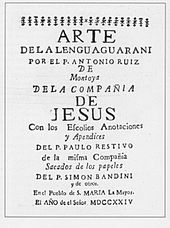

In some reductions such as Corpus, San Miguel, San Xavier, Loreto, Santa Maria la Mayor, book printing shops were set up, where mainly books for liturgy and asceticism were produced. The high degree of commercial development after the end of the 17th century could only be achieved when a larger number of Jesuits from Germany (e.g. Johann Kraus or Joseph Klausner, who introduced the first pewter foundry in the province of Tucuman), Switzerland (e.g. B. Martin Schmid ) and Holland arrived in Paraguay. At that time, arts and crafts were completely neglected in the Spanish colonies.

Cooperation of the reductions

The flourishing exchange of goods took place, even under the reductions themselves, basically without money. This only played a role in centralized foreign trade. Export goods were mainly cotton and mate tea in addition to cattle hides. Taxes were paid to the Spanish crown from the proceeds of the reductions achieved after the demand was met.

Horses were also used for solemn processions or festive occasions. The reduction "Los Santos Apostelos" once had 599 such Caballos del Santo .

Culture transfer

understanding

The Jesuits proselytized in an unconventional way by respecting the thinking of the locals and adapting to their training and living habits. In order to work efficiently with the local people, the missionaries learned their languages. To do this, they wrote dictionaries, translated the Bible and other texts that they printed themselves. In this way the native languages were preserved; in special cases (Guaraní and Chiquito) a common new language emerged from a variety of dialects. The Guaraní language has been preserved in Paraguay as an official language alongside Spanish to this day.

After deducting taxes to the Spaniards, the wealth generated in the reductions was also invested in cultural values such as education, art and magnificent church buildings.

The music state

This term denotes an important component of inculturation . In addition to all the artisanal and rural transfers, the locals were also taught musical values. Singing and making music were accepted with particular enthusiasm and encouraged by the Jesuits. Musical instruments were also built according to European models. A new style of music and new musical notes were also created. Music accompanied the way to work and shaped church services, festivals and celebrations.

The greatest composer and organist was Domenico Zipoli , who left a great deal of work after his work from 1716 to 1726. His sheet music was rediscovered by the architect Hans Roth in old Jesuit churches in Bolivia and edited by P. Piotr Nawrot SVD. The Paraguayan conductor Luis Szarán recently arranged Zipoli's music. The music of the reductions can be heard again today in South American churches and in concerts in Europe.

Success and failure

The reductions were the strongest bulwark of Spanish rule. The fact that the locals received protection from slavery, secure daily routines, community and, especially with the Guaraní, spiritual accompaniment, appears to be the main reason for the great success of these settlements. The superiority of the Jesuits in the organization and smooth functioning of communities and agriculture also contributed to this.

Already at the time of the Jesuit state, believers and unbelievers, intellectuals such as enlighteners, poets and historians were fascinated by the “sacred experiment” of reductions, because it linked religion with the idea of humanity. The socialists of the Enlightenment also saw this experiment as a model source for reforms.

The fundamental endeavor of the Jesuits was the conversion of the locals to Christianity. It was not intended to combine existing tribal structures with the community structures of a European order for a fruitful encounter between two cultures in order to create a model for a future pioneering social or state order. There was no real emancipation approach for the locals. In this way the roles were and remained distributed: the locals remained at the dependent level. Well-intentioned authorities have also declared that the locals had not been trained to be autonomous and that the Jesuits enabled them to remain immature. An exchange in partnership on the same level could not come about.

Paradise lost

Jesuit Reduction, Alta Gracia , Argentina

Front entrance of the Reduction Church in San Javier (Santa Cruz) , Bolivia

Interior of the Jesuit Reduction Church Iglesias de las Misiones , Concepción, Dept. Santa Cruz Department , Bolivia

Restored Jesuit Reduction Church in San Ignacio de Velasco , Bolivia

Church of the Jesuit Reduction Santa Ana de Velasco , Santa Cruz Department, Bolivia

Detail at the church portal San Rafael , Santa Cruz, Bolivia (Jesuit missions of the Chiquitos)

The independence efforts of the local leaders of the so-called Antequera riots ( Usurper Antequera) and the Comuneros uprising in New Granada harassed the Spanish crown as early as 1721 to 1735 and again later. But the locals always remained loyal to King Philip V , which he confirmed by decree on December 28, 1743 at a grand celebration. In contrast to the colonialists, the missionaries took the side of the oppressed indigenous population. The defeated insurgents now concentrated their anger on the Jesuits and the locals living in the reductions.

The colonialists' sinister criticism of the reductions became louder and louder. The European slave traders and landowners were annoyed about the isolation of the natives in the reductions and the strict prohibition of Spaniards from entering the reduction territory. European traders, merchants and local colonial authorities became increasingly jealous of the resounding success of the Jesuits in the reductions. The reductions were based on the assumption that the fathers did not teach the locals the Spanish language for the reason that they could not endanger the secrets of the Jesuits. Wildest rumors and slander were now circulated by the Jesuit opponents. Many untruths were ascribed to the reductions, such as: B. an annual tea export of 4 million pounds or 300,000 locals as workers in the reductions. Likewise, in Europe, fanciful rumors and myths full of lies developed out of stoked hatred and greedy resentment: from the amassing of immense wealth of the Jesuits from colossal trade profits, gold mines in the reductions, large herds of cattle on the farms and rebellion intentions with the help of the Indian armies.

The representatives of the crown took these allegations seriously: As early as 1640 and then also in 1657 by the then rector of the Peruvian National University, Juan Blásquez de Valverde , corresponding investigations were carried out. In both cases, however, the allegations made were refuted: According to official sources, the annual export of tea was only 150,000 pounds, in the best case 150,000 adults and children worked in the reductions. The reproaches persisted, however, so that now the free-thinking ministers of France Étienne-François de Choiseul , of Portugal Sebastião José de Carvalho e Mello and of Spain the Count of Aranda Pedro Abarca agreed to intervene with their kings. The government was forced to order several more investigations.

The treaty of 1750

The difficulties between Spain and Portugal over the border disputes over their American possessions gave the influential Portuguese supporter of enlightened absolutism Sebastião José de Carvalho e Mello - a mortal enemy of the Jesuits - the opportunity to reach an agreement that was in the interests of Portugal and Carvalho e Mello's personal dislike was useful to the Jesuits. The treaty concluded in Madrid on January 25, 1750 included that Spain could keep the controversial colony of San Sacramento at the mouth of the Uruguay, and that in return the seven reductions on the left eastern bank of the Uruguay were ceded to Portugal, i.e. H. about 2/3 of today's province of Rio Grande do Sul and one of the most valuable parts of the La Plata area . It was also agreed that all missionaries and their 30,000 natives living in the reductions would have to leave the reductions immediately with bag and baggage in order to resettle on the right bank of Uruguay. The missionaries and locals concerned only found out about it afterwards.

Robert Southey described this decision, which after 150 years of building up sensible colonial policy or economic viability, was “one of the most tyrannical decrees ever issued by the ruthlessness of a callous government”. He also noted that the then weak King Ferdinand VI. had no idea of the importance of this contract.

The Spanish colony of La Plata was surprised by this treaty and reacted indignantly. Protests by the Viceroy of Peru José de Andonaegui , the royal Real Audiencia of Charcas etc. as well as petitions from the Jesuits were unsuccessful. Therefore, the then superior general of the Jesuits, Ignazio Visconti , reluctantly ordered to obey the contract and to inform the locals accordingly.

From 1754 the name “Reductions” was officially changed to “Doctrinas”. The mission stations were treated as parishes; each parish was headed by a pastor and a vicar, in larger parishes several pastors.

After the relocation order

The locals asked for the action to be postponed and made efforts to obtain a revocation, merely doing their job to counter the allegation of disobedience. Their position was aggravated by the behavior of the Spanish and Portuguese plenipotentiaries, particularly the attitude of the General and King-appointed Executor Luis Altamirano SJ, who treated his friars like rebels, although they advised him to proceed carefully and moderately. Despite objections from the fathers, the locals armed themselves and in 1753 unleashed the so-called "War of the Seven Reductions" in which they were bitterly beaten. The locals who did not surrender fled into the woods to continue fighting, unsuccessfully. The larger number of locals followed the advice of the fathers and moved to the reductions on the right bank of the Uruguay or those on the Paraná . In 1762 11,084 natives lived in 2,497 families in 17 reductions. In 1781, 14,018 locals in 3,052 families had returned to their old homes, because in that year Spain canceled the treaty of 1750 and thereby admitted the mistake made at the time.

The " war of the seven reductions " was now used as the main charge by the Jesuits' fiercest opponents. From an unscrupulous press controlled by Sebastião José de Carvalho e Mello, a flood of slanderous pamphlets, forged documents and fables by the anti-Jesuit party was spread across Europe. Although their unhistorical character has long been established, these publications continue to skew the historical account of this period.

After the Jesuits were expelled from Portugal in 1759 , from France in 1764 and from Spain in 1767 , they suffered the same in the reductions: They were arrested overnight and disembarked for their European homeland. On April 2nd, 1767, the weak and duped King Carlos III signed the decree banning the Jesuits from Spanish property in America. This was the death knell for the Paraguayan reductions.

The eviction of the Reduction residents was carried out by the governor of La Plata Bucarelli using brutal force. The Jesuits humbly submitted to the sad fate, although they could probably have successfully opposed the verdict by force.

Robert Cunninghame Graham writes : “The Jesuits in Paraguay convincingly confirmed their loyalty to the Spanish crown, at least through their conduct in their last public acts. Nothing would have been easier for them than to defy the exhausted troops that Bucarelli had at their disposal in order to build a Jesuit state that would have overwhelmed the last possibilities of the Spanish government. But they renounced resistance and submitted like sheep that are brought to the butcher. ”(Loc. Cit., 267)

At that time the Jesuit Province in Paraguay comprised 564 Jesuits, 12 high schools, 1 university, 1 novitiate, 3 rest homes, 2 headquarters, 57 reductions with 113,716 Christian locals. Saying goodbye to the Jesuits by the locals was painful. They pleaded in vain to be allowed to keep their fathers or to be sure that they would return. They never returned.

The reductions after the expulsion of the Jesuits

A progressive economic decline resulted from these events. At the beginning of the 19th century, the states of Paraguay, Argentina and Brazil formed in many armed conflicts over the definition of the national borders. Many reductions were destroyed in the process, but former reductions or their farms and estates also developed into larger towns such as B. Alta Gracia.

Soon after the eviction, disillusionment spread. Except for the splendid decorations of the churches, from which whole truckloads were transported, and insignificant amounts of money, none of the hoped-for treasures were found. The huge trade profits assumed for the reductions turned out to be false assumptions. The large herds of cattle could not be counted as assets, as no one really owned the widely scattered grazing cattle.

Some reductions were subsequently robbed and destroyed by armed expedition troops, and many residents were sold as slaves. The management of the reductions was entrusted to civil administrators within the framework of the colonial state, the spiritual administration of the reductions was entrusted to the Franciscans and other clergymen. From 1768 the reductions were directed by the Spanish civil administration; Suitable persons were newly appointed for all offices. Local leaders were entrusted with important administrative and military positions.

After the Jesuit expulsion, the Spanish viceroy Bucarelli urged in his instructions to his successor to maintain the system of isolation of the natives in their interests. Attempts were made to keep most of the institutions established by the Jesuits. But the rapid decline of the reductions (the Guaraní Reduction, for example, had 80,881 inhabitants in 1772, only 45,000 in 1796; soon afterwards only a few remains) showed that their earlier economic and political importance was a thing of the past. After the wars of independence and finally the despotic rule of the first republican presidents and dictators Francia and Lopez , the reductions were practically meaningless.

reception

The Jesuit reductions were celebrated for centuries, especially among Catholic circles, as a utopian experiment which, according to many contemporaries, promised “Christian sacrifice” and an enormous progressiveness through a Christian order.

Konrad Haebler writes in the yearbook of historical science 1895: “Whatever one can say about the Jesuit missions, they absolutely deserve the praise that their settlements were the only ones where the locals did not die out, but increased.” Stein - Wappäus : “The memories to the missionaries still live on as a blessing among the Indians, who speak of the rules of the fathers as their golden age ”(loc. cit., 1013). Karl von den Steinen : “The fact is that the expulsion of the Jesuits was a heavy blow for the indigenous people of La Plata and the Amazon region, from which they never recovered.” A scholar from the high school in Cordoba summed up: “The Jesuits led the Reductions - as strange as it seems - not like a business, but more like a utopia: These stupid guys think happiness is preferable to wealth ”.

The reductions today

Church ruins of the Jesuit Reduction São Miguel das Missões , Brazil

The churches built in the locally modified colonial baroque (wooden hall structures) in the reductions have partially fallen apart or in ruins, many of them have been completely renovated by the Swiss Hans Roth SJ from 1972 to 1979 and are still in use.

World heritage

Today mostly only ruins mark the places where the great Christian communities once stood. Others have been restored at great expense. The following churches and reduction facilities are recognized as UNESCO World Heritage .

- Guaraní in Paraguay: La Santísima Trinidad de Paraná and Jesús de Tavarangüe , Santos Cosme y Damián

- Guaraní in Brazil and Argentina : San Ignacio Mini , Santa Ana, Nuestra Señora de Loreto and Santa Maria Mayor (Argentina), ruins of São Miguel das Missões (Brazil)

- Chiquitos in Bolivia: San Javier (Santa Cruz) , Concepción (Santa Cruz) , Santa Ana de Velasco , San Miguel , San Rafael , San José

- Córdoba in Argentina: Jesuit quarter with a baroque church, university, college

Representations

Theater, film

- Play: Fritz Hochwälder's sacred experiment from 1942

- Film: Mission 1986 by Roland Joffé with Robert De Niro and Jeremy Irons based on the drama The Sacred Experiment

literature

- Clovis Lugon: La république comuniste chrétienne des Guaranis (1610–1768). Edition "Ouvrières Économie & Humanisme", Paris 1949.

- Heinrich Boehmer (Ed. Kurt Dietrich Schmidt ): The Jesuits. KF Koehler, Stuttgart 1957.

- Hans-Jürgen Prien: The history of Christianity in Latin America. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1978, ISBN 3-525-55357-9 .

- Peter Strack: Before God, community and guests: functions and changes in traditional festival symbolism. For regional history, Bielefeld 1991, ISBN 3-927085-51-0 .

Specialist literature

- Elman R. Service: Spanish-Guarani Relations in Early Colonial Paraguay. University of Michigan, 1954.

- Wolfgang Reinhard: Guided cultural change in the 17th century. Acculturation in the Jesuit missions as a universal historical problem. In: Historical magazine. 223, 1976, pp. 535-575.

- Philip Caraman: A Paradise Lost. The Jesuit state in Paraguay. Kösel, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-466-42011-3 .

- Felix Becker: The political power of the Jesuits in South America in the 18th century. On the controversy surrounding the "Jesuit King" Nicholas I of Paraguay; with a facsimile of the “Histoire de Nicolas I” (1756). Böhlau, Cologne / Vienna 1980, ISBN 3-412-07279-6 . (= Latin American research . Volume 8, also a dissertation at the University of Cologne 1979 under the title: "King Nicholas I of Paraguay and the Guaranite War" )

- Gerd Kohlhepp : Jesuit Guarani Reductions in North Paraná. In: Paulus Gordan (ed.): For the sake of freedom. A festival for and by Johannes and Karin Schauff. Neske, Pfullingen 1983, ISBN 3-7885-0257-6 , pp. 194-208.

- Peter Claus Hartmann: The Jesuit State in South America 1609–1768. A Christian alternative to colonialism and Marxism. Konrad, Weißenhorn 1994, ISBN 3-87437-349-5 .

- Piotr Nawrot Teaching of Music and the Celebration of Liturgical Events in the Jesuit Reductions . In: Anthropos , Vol. 99, No. 1 (2004), pp. 73-84.

- Rolf Decot (ed.): Expansion and endangerment. American Mission and European Crisis of the Jesuits in the 18th Century. von Zabern, Mainz 2004, ISBN 3-8053-3432-X ; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2009, ISBN 978-3-525-10075-2 . (= Publications of the Institute for European History, Mainz , Supplement 63: Department for Occidental Religious History)

- Goethe-Institut Córdoba (ed.): Para una cultura del entendimiento. Las misiones jesuíticas en Latinoamérica / For a culture of understanding. The Jesuit Mission in Latin America. Goethe-Institut Córdoba, Córdoba 2010, ISBN 978-987-22318-3-5

- Fabian Fechner: On-site decision-making processes. The provincial congregations of the Jesuits in Paraguay (1608–1762) (= Jesuitica. Sources and studies on the history, art and literature of the Society of Jesus in German-speaking countries, vol. 20) Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner 2015. ISBN 978-3-7954-3020-7

- Guillermo Wilde: Religión y poder en las misiones de guaraníes , Buenos Aires 2009. ISBN 9789871256631

Fiction

- Fritz Hochwälder: The sacred experiment. Play. Reclam, Stuttgart 1964. (1971, ISBN 3-15-008100-9 )

- Alfred Döblin: Amazon. Novel trilogy. dtv, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-423-02434-8 . (First edition Amsterdam 1937/1938)

- Drago Jančar: Catherine, the peacock and the Jesuit. Roman, from the Slovenian by Klaus Detlef Olof. Folio, Vienna 2007, ISBN 978-3-85256-374-9

Other sources

- Ruiz de Montoya: Conquista Espiritual. Madrid 1639.

- A. Kobler (ed.): Father Florian Baucke , a Jesuit in Paraguay (1748–1766). According to his own notes. Pustet, Regensburg 1870.

- Nicolás del Techo: Historia de la provincia del Paraguay de la Compañia de Jesús : CEPAG, Asunción 2005, ISBN 9-9925-8953-1 ; ( Reprinted from the Historia Provinciae Paracuaria Societatis Iesu , Liège 1673).

Sound carrier

- CD: Domenico Zipoli, Martin Schmid, Francisco Varayu: Baroque Jesuit music from the primeval forests of South America. Conductor Luis Szarán, Dia-Dienst-Medien Munich T 2008 CD 05146

- CD: Klaus Väthröder SJ (Ed.): Jesuitenmission.de: “Weltweit Klänge 3”, concert by the international youth orchestra of the Jesuit Mission in Nuremberg on November 13, 2008, overall direction Luis Szarán

- CD: Rita Haub: The History of the Jesuits . Darmstadt, Auditorium Maximum, 2010, ISBN 978-3-534-60149-3

See also

- Abolition of the Jesuit order in 1773

- Jesuit reductions of the Guaraní

- Jesuit reductions of the Chiquitos

- List of churches of the Jesuit missions of the Chiquitos

- List of churches of the Jesuit missions of the Chaco

Web links

- Jesuit Mission Germany

- Jesuit reductions in Argentina (Spanish)

- The South American Utopia of the 18th Century (German)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Peter Balleis: Passion for the world. Echter, Würzburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-429-02885-5 , pp. 34, 35, 36.

- ↑ Ulrich Schmidel, a Landsknecht in the service of the Conquistadors. on: kriegsende.de (report by a Landsknecht)

- ^ A b c Hans-Theo Weyhofen: The Jesuit reductions in Latin America. ( Memento from August 8, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Beat Ammann: Social Engineering to Indios in Bolivia. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung. April 2, 2008, Retrieved October 24, 2012

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Reductions of Paraguay. In: The Catholic Encyclopedia. (English)

- ↑ a b c Uwe Schmengler: The Jesuit State of Paraguay: Objective and method of mission. ( Memento from September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The Jesuit Missions - An unforgettable missionary work in the primeval forests of South America 1609–1767. (Brochure)

- ↑ Robert et al. Evamaria Grün (ed. And edit.): The conquest of Peru. Pizarro and other conquistadors 1526–1712. The eyewitness accounts of Celso Gargia, Gaspar de Carvajal and Samuel Fritz. Tübingen 1973, pp. 291–330 (most recently published as a fully, thoroughly, and abridged new edition by Ernst Bartsch and Evamaria Grün (eds.): Stuttgart / Vienna 1996, ISBN 3-522-61330-9 ).

- ↑ a b c d Bernhard Kriegbaum: The Jesuit reductions (1609–1767).

- ↑ a b Bernhard Matuschak: Father Schmid's legacy. In: Wiener Zeitung. April 9, 2004, Retrieved October 24, 2012

- ^ Piotr Nawrot: Domenico Zipoli, 1688-1726. Scoreas. A 30 años del descubrimiento. Fondo Editorial Asociación Pro Arte y Cultura (APAC), Santa Cruz de la Sierra (Bolivia) 2002. 5 volumes, ISBN 99905-1-028-8 , ISBN 99905-1-029-6 , ISBN 99905-1-030-X , ISBN 99905-1-031-8 , ISBN 99905-1-032-6 .

- ↑ Luis Szarán: Jesuit settlements in South America - gloss and decay of musical art . In: Jochen Arnold u. a. (Ed.): Sounds of God. Music as a source and expression of the Christian faith . Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2013, ISBN 978-3-374-03290-7 , pp. 211–220.

- ↑ Julia Urbanek: Mozart instead of cobblestone. In: Wiener Zeitung. January 22, 2011. Retrieved October 24, 2012

- ^ A b Heinrich Krauss, Anton Täubl: Mission and Development of the Jesuit State in Paraguay. Five-part course in the media network; Kösel, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-466-36051-X , pp. 158, 170.

- ↑ Historical Lexicon of Switzerland: Short biography of Martin Schmid

- ↑ UNESCO World Heritage: Jesuit Missions of the Guaraní in Paraguay (English)

- ↑ UNESCO World Heritage: Jesuit Missions of the Guaraní in Brazil and Argentina (English)

- ↑ UNESCO World Heritage: Jesuit Missions of the Chiquitos (English)

- ↑ UNESCO World Heritage: Jesuit Quarter and Reductions (English)

- ↑ Matthias Herndler Presentation: "The Holy Experiment" (PDF; 53 kB)

- ↑ referate.online: The Holy Experiment