Penrhyn Castle

Penrhyn Castle is a Norman castle- style country castle in the northern Welsh parish of Llandygai , Gwynedd , about two kilometers east of central Bangor . Its roots lie in a medieval permanent home of the Griffith family, which was replaced by a new building in the style of the Scottish Baronials in the second half of the 18th century by Richard Pennant, 1st Baron Penrhyn . After George Hay Dawkins inherited the property, he had the existing building replaced between 1821/1822 and 1837 by the current system based on designs by the architect Thomas Hopper , whereby the old structure was integrated into the new building. Since then, the system has only been slightly changed and is considered to be Hopper's masterpiece.

The castle stands since 3 March 1966 as Listed Building of stage I under monument protection , with outbuildings such as the monumental entrance gate or the ruin of the former castle chapel is a listed building separately. The castle park and garden are also under monument protection with level II *. The main country estate in Wales, the complex is a fine example of the early 19th century neo-Norman style that was only popular for a short time. With its enormous dimensions and approximately four hectares of floor space, Penrhyn is the largest castle building in the British Isles after Windsor Castle .

history

middle Ages

In the 13th century Goronwy ap Ednyfed received from the Prince of Gwynedd about 500 acres (over 200 hectares ) of land, which was already colloquially called Penrhyn ( Welsh for promontory). The property was divided among his descendants before Gwilym ap Gruffyd (later spelled Griffith) reunited the property in one hand around 1380/1390 by marrying Morfudd. Previously, either Tudor ap Goronwy or his son Goronwy ap Tudor had built a first permanent house on the property. Gwilym ap Gruffyd joined Owain Glyndŵr's rebellion against the English king in 1402 , with the consequence that he had to submit to Henry IV in 1406 and all his goods were confiscated . However, he managed to buy back his possessions in November 1407. Later he not only acquired the confiscated land from 27 other rebels, but from 1410 onwards he also systematically bought additional land. The old core property was now officially called Penrhyn. The house the family was first mentioned in a lease agreement in 1413, and in 1438 a permit was his attachment ( English license to crenellate granted). This was no longer given to Gwilym ap Gruffyd, but to his son from his second marriage, Gwilym Fycham. He had succeeded his father in 1431 and added further lands to the property by purchasing them. Penrhyn passed through his son to grandson William Griffith, who had his family resident renewed. William was inherited by his son Edward, who left three daughters from his marriage to Jane Puleston of Bersham on his untimely death on March 11, 1540. Edward's younger brother Rhys claimed the inheritance as the closest male relative and argued over it with his nieces' families. A court finally ruled in 1542 that Griffith's holdings should be divided: all land in Anglesey went to Edward's daughters, while Penrhyn belonged to Rhys from now on. Like his father, he made changes to the house. When he died on July 30, 1580, he was followed by Piers (also written as Pyrs), the eldest son from his third marriage. At the time, however, he was only 12 years old and could not take over his inheritance until 1591. In the following year Piers pawned part of the property, and further pledges followed until 1616. That year he was detained in London's Fleet Prison at the instigation of his father-in-law, Sir Thomas Mostyn . The reason for this was high debts due to his marriage contract. Only a little later, Penrhyn came completely to Jevan Lloyd of Iâl, who had previously acquired many parts of the property. He sold Penrhyn in 1622 to John Williams , Lord Keeper of the Great Seal and later Archbishop of York .

Property of the Griffith and Pennant families

John was a distant relative of the Griffith of Penrhyn family, being a descendant of Gwilym ap Gruffyd's younger brother Robin. It is known that he planned to rebuild the old house, but no documents exist on whether this project was actually carried out. At his death in 1650 he bequeathed Penrhyn along with other estates to his nephew Griffith Williams, who was appointed baronet by Oliver Cromwell in 1658 . This was lifted after the Cromwell era, but King Charles II renewed this appointment in 1661. Via Griffith's son Robert, the property was passed on to his son John, after whose childless death in 1682 his brother Griffith, the 4th baronet, inherited it. But Griffith also had no heirs, so the title of baronet went to Hugh Williams of Marl, Griffith Williams' third son, while Penrhyn went to his sister Frances. She left the property to her two sisters Gwen and Anne in 1714. Gwen's granddaughter Anne Yonge sold her stake in 1767 to Edward Pennant, the wealthy owner of sugar plantations in Jamaica . His two sons, John and Henry, began buying back land that had previously belonged to Penrhyn. John's son and heir Richard Pennant had married Ann Susannah Warburton on December 6, 1765. She was the granddaughter of Anne Williams, who married Sir Thomas Warburton of Winnington Hall . She was also the heir to General Hugh Warburton, who owned the other half of Penrhyn. After the death of father, uncle and father-in-law, ¾ of the Penrhyn estates were reunited in the hands of Richard Pennant. He finally bought the rest of the quarter from the Yonge family in 1785. Richard and his wife did not live in the old Williams family home, but lived in Winnington Hall near Northwich . Instead, Richard's brother Samuel used it as a residence. Richard had it rebuilt and modernized for him in the style of the Scottish Baronial based on designs by Samuel Wyatt . The medieval predecessor building was integrated into the new building made of yellow bricks . The hall became a vestibule and the house received another wing with living rooms. In addition, the old chapel was torn down stone by stone and rebuilt at its present location in the park . The stables were also given a new location. The old stables were demolished and new brick stables were built north of the house. There was also an imposing entrance building on the edge of the park, which had the shape of a triumphal arch . The renovation work was finished before 1780. Around 1800 Pennant, who had been promoted to Baron Penrhyn in 1783 , had the building changed again. When he died in Winnington in 1808, there had been no children from his marriage and so after the death of his widow in 1816 his property went to the grandson of Richard's sister, George Hay Dawkins.

Expansion in neo-Norman style

The new owner added the coat of arms and the name of the Pennant family to his own and was called Hawkins-Pennant from then on. He had the out-of-date Penrhyn house rebuilt according to designs by architect Thomas Hopper in the neo-Norman style, a trend in neo-Gothic style. Hopper had already built two castles of this style in Ireland: Shane's Castle in County Antrim and Gosford Castle in County Armagh . William Baxter was in charge of all work. As early as 1819, the lord of the castle had the castle park enclosed with a new surrounding wall, but construction work on the house did not begin until 1821/1822. The exact start of construction is not known, but when Hermann von Pückler-Muskau visited the property in 1828, work is said to have been in progress for seven years. 1826 were Great Hall ( English Grand Hall and Great Hall ), the library tower ( English Library Tower ) and the Oak Tower ( English Oak Tower completed). The work on the masonry of the keep and the other important towers also seem to have been completed. Construction on the large entrance gallery began in 1829; its massive oak entrance door was not installed until 1835. The stables built under Richard Pennant were renewed and expanded between August 1831 and June 1833. During the years of renovation, the lord's family lived in a simple house near Colwyn , but they moved into their new domicile while the construction work was still ongoing. By 1837, not only had all the buildings been completed and furnished, but the castle park was also enlarged to the north and large parts of it were replanted, including many exotic plants. A lot of slate was used for all work in and on the buildings , because George Hay Dawkins-Pennant owned a very lucrative slate quarry near Bethesda, seven kilometers away . The cost of the new building is said to have been £ 150,000. When the client died in 1840, Juliana Isabella Mary, his eldest daughter from his marriage to Sophia Mary Maude in 1807, inherited Penrhyn Castle. She had been married to Edward Douglas since 1833 and brought the extensive property to his family. Edward Douglas also added the coat of arms and the name Pennant to his own after the inheritance. After the untimely death of his wife in April 1842, he married Maria Louisa Fitzroy, daughter of Henry FitzRoy, 5th Duke of Grafton , in 1846 . The family lived on Penrhyn for only a small part of the year, spending most of their time in Wicken Park and their London townhouse, Mortimer House on Halkin Street. In October 1859 Edward and his wife received a distinguished visit to their country estate: Queen Victoria and her husband Albert stayed in Penrhyn for a few days. A slate bed weighing tons, which can still be seen in the palace today, was purchased for the queen especially for this occasion. The children of the hosts had to be accommodated in the Hotel Penrhyn Arms in Bangor for the duration of the distinguished visit in order to have enough space in the castle for the accommodation of the court. During her stay, the monarch planted a giant sequoia on the meadow west of the complex , which is called the Queen’s Tree and is still there today.

By the middle of the 20th century

Edward Douglas-Pennant, for whom the title of Baron Penrhyn was newly created in 1866, bequeathed the castle to his son George Douglas-Pennant, 2nd Baron Penrhyn, on his death on March 31, 1886, via whom it was passed on to Edward Douglas in March 1907. Pennant, 3rd Baron Penrhyn, came. At that time, Penrhyn was hardly used by the family. A hunting party stayed in the buildings very rarely, and the number of servants was reduced to a minimum. At the weddings, 44 domestic servants were employed at Penrhyn Castle. It was not until Edward's son Hugh Douglas-Pennant, 4th Baron Penrhyn, came into his heir in 1927 that the castle was regularly used again. He made it his main residence with his wife Sybil, daughter of the 3rd Viscount Hardinge , and gave lavish house parties there on the weekends in the 1920s and 1930s. The couple also made some changes and modernizations. The neon-Norman style furniture specially designed for the castle was replaced by modern furniture and the building was supplied with electricity. In the garden, plant the so-called carried Rhododendron reasonably ( English Rhododendron Walk ) and the transformation of the terraced Walled Gardens by the hostess. During the Second World War , the plant served as the main location of the Daimler Motor Company from 1940 to 1945 . The National Gallery was during the war years at times some paintings of Old Masters in Penrhyn store, because the castle was one of the few buildings in the kingdom, whose doors were large enough to Anthony van Dyck's equestrian portrait of Charles I of England (the largest painting in the collection ). On his childless death in 1949, Hugh bequeathed the property to his niece, Janet Marcia Rose Harper, while the title of Baron Penrhyn went to a second uncle. In accordance with her uncle's testamentary provisions, the new lady of the castle and her husband John Charles Harper took the surname and coat of arms of the Douglas-Pennant family. However, the two only lived in the castle for a few months in 1949 before moving into the former gardener's house in the kitchen garden. In 1959 they had this enlarged by adding two side wings.

Todays use

In 1951, the castle building and 40,000 acres (more than 16,000 hectares ) of land came to the state as compensation for a tax payment, which subsequently transferred it to the National Trust. The parkland belonging to the property - like the valuable collection of paintings in the castle - still belongs to the Douglas-Pennant family, who still live in the former gardener's house, known as Penrhyn House . The National Trust opened the facility to the public in 1952. Many rooms of the castle can be viewed with their original furnishings. This also includes the extensive collection of paintings, mainly compiled by Edward Gordon Douglas-Pennant, which earned the castle the nickname Gallery of North Wales . It includes works by Rembrandt , Aert van der Neer , David Teniers the Younger , Thomas Gainsborough , Allan Ramsay , Antonio de Pereda , Canaletto , Clarkson Stanfield and Carl Haag . In addition, three different museums are housed in the castle. On the upper floor of the horse stable an exhibition informs about the history of the property and the current measures for its maintenance. In the doll museum, which is set up in the Keep on the floor of the former children's room, you can see dolls and dollhouses from the 19th and 20th centuries. The Penrhyn Castle Railway Museum has been located on the west and south sides of the stable area since 1965 . It shows old locomotives that were used in freight transport in the 19th century, including the fully restored Fire Queen , one of the first steam-powered locomotives on the Padarn Railway .

description

location

The castle stands on a hill north of Llandygai between Snowdonia National Park in the south and the Menai Strait in the north. On the opposite side of the strait on the island of Anglesey, the ruins of Beaumaris Castle are just four kilometers away . With Conwy Castle in the Northeast and Caernarfon Castle in southwest two other major Welsh castles are within only 19 kilometers.

architecture

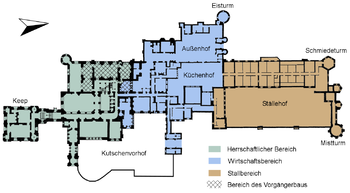

The castle is an elongated ensemble of buildings measuring 182.88 meters in a north-south direction. Its silhouette is determined by eleven towers, numerous tourelles and battlements that are typical of the neo-Gothic style. The architecture of the complex is similar to Raglan Castle . Its masonry is made from local quarry stone with layers of brick clad with dark gray limestone from Penmon , also known as Anglesey marble . The 70 roofs of the ensemble cover an area of around 0.4 hectares. There are three different lock areas. The southern part, including the keep, is taken up by the stately rooms and parade rooms . The middle section of the ensemble consists of the 150-meter-long utility area with utility buildings and rooms for the staff. It takes up more floor space than the stately rooms. The economic area is followed by the more than 200 meter long Ställehof ( English Stables Court ) to the north , which in addition to the spacious horse stables accommodated other utility rooms .

Manorial area

The visitor approaches the castle from the north and reached by a gatehouse, which was once the main gate of the previous building, the coach atrial ( English Carriage Forecourt ). This lays like a barbican in front of the east facade of the manorial rooms and has machicolations on the east and north sides. Its surface consists partly of lawn and partly of gravel . A one meter high stone parapet surrounds the courtyard. From there, the manorial area can be entered through a massive portal with the coats of arms of the Dawkins and Pennant families. On the west side of the manorial rooms, in the library area, the 18th century house is integrated into the current building. An unchanged basement with barrel vaults and a stair tower still used as such are evidence of this. In the very south of this area is the square, four-story keep, modeled on the tower of Hedingham Castle . Its edge length is 62 feet (approx. 18.9 meters) with a height of 37.8 meters. Four square corner towers sit at the corners of its top floor. Inside were the private apartments of the owner family.

Economic sector

A transition rule rooms with the kitchen courtyard were ( English Kitchen Court ) connected. This area includes dining rooms for the servants, kitchens, pantries, accommodations for the female servants, a coal cellar, storage rooms for dishes and household linen as well as a bakery, a scullery and a laundry. From Küchenhof was Bailey ( English Outer Court ) with its own gatehouse, soup kitchen, brewery and the massive ice tower ( English Ice Tower ) with machicolations reach. The latter got its name from its use as an ice cellar, which continued into the early 20th century . In winter, ice was fetched from the flooded banks of the Afon Ogwen and stored in a room in this tower. This room has a conical shape and with a total of 7.5 meters takes up the height of the basement and ground floor. Its diameter is three meters on the ground floor, while it is only one meter on the floor in the basement. Food may have been stored in the room above the ice cellar in the past.

Stable yard

The northernmost part of the castle is the so-called Ställehof , around which stalls for up to 36 horses, the coach house and former accommodation for male servants are grouped. Access to this area was provided on the north side by a gate flanked by two towers, above whose archway a clock from 1795 hangs. The two northern corners of this area are marked by the hexagonal forge tower ( English Smithy Tower ) and the manure tower ( English Dung Tower ) with its crowd watch tower . In the western stables there were two rows of stable boxes, a saddle room , storage rooms and accommodation for the grooms. The upper floor used to be the granary and the room for the coachman. Today there is an exhibition on the history of the castle.

inside rooms

A lot of stucco and richly carved stone and wood elements were used for the interior design based on Thomas Hopper's designs . The furnishing was done in the eclectic style as a mixture of Norman, Baroque , Oriental and East Asian influences. Much of the furniture and even carpets were made especially for Penrhyn Castle by local craftsmen in neo-Norman style. In the 1920s they were relegated to the granary by their owners at the time. When the National Trust took over the facility, he put it back in its original location.

Behind the massive entrance door of the castle portal is a long corridor with a vaulted ceiling, which, thanks to its design, gives the impression of a cloister. He could be illuminated with lamps made of bronze in the form of wolf heads, which stand on stone pedestals. Initially they were operated with oil, later with gas, before electricity was installed in the castle in 1927/1928. The long corridor leads to the Great Hall , which, with three floors, takes up the entire height of this part of the castle. In terms of size, it is more like a covered courtyard than a room. It is the link between the living rooms in the Keep, the reception rooms of the castle and the utility area. The stained glass windows were made by Thomas Willement , the leading glass painter in the kingdom at the time . They show signs of the zodiac and representations of the months, as was customary in medieval books of hours . The great hall and the adjoining rooms could be heated by a hot air system. The construction required for this was one of the first of its kind on the British Isles. Both on the ground floor and from a gallery at the level of the first floor, a corridor leads from the hall to the keep in the south with the private living rooms for the owner family. The two top floors of the tower could only be reached via spiral stairs in the corner towers. One of them was for the service staff. In all four floors of this tower is an apartment with living room / lounge ( English sitting room ), dressing room , bedroom, small anteroom and bathroom. The castle's most famous piece of furniture is in one of the bedrooms: a bed made from slate based on a design by Thomas Hopper that weighs over a ton . Other pieces of equipment include the wallpaper by William Morris and a fireplace made of red marble from the island of Mona .

The library is to the west of the Great Hall . It is divided into two halves by a wooden arcade with four flat arches. The arches used to be intricately sculpted, but this decoration was removed in the 1930s. The arches found their counterpart in the richly carved stucco ceiling with representations of the coat of arms of the castle owners, starting with the Dawkins family to the Pennant families. Heraldic representations in the form of the coats of arms of royal and aristocratic Welsh families can also be found in the large stained glass windows of the room . They may have been made by the glass painter David Evans of Shrewsbury. With its furniture, oak paneling and four chimneys made of polished Penmon limestone, the room conveys the atmosphere of a gentleman's club. The library's bookcases are shaped like ancient temples . They include two rare and valuable books that came to the National Trust in 2002 to replace tax payments. These are, on the one hand, the book Ruins of Palmyra by Robert Woods , published in 1753, and, on the other hand, Charles Wilson's Ordonance Survey of Jerusalem , a work published in 1865 with early photos of the Ottoman Jerusalem . The drawing room next to the library , a kind of living room, is characterized by its vaulted ceiling with 2000 stucco and golden painted Maltese crosses . Its stained glass windows with coats of arms are by David Evans of Shrewsbury. The wall covering made of silk lampas is no longer original, but was remade in 1985 based on a piece of the original covering that was still preserved. From the Drawing Room , the so-called is Ebony Room ( english Ebony Room ) distance. It takes its name from its furniture, which is either made entirely of ebony or has a veneer made from this material. The fireplace made of black and polished limestone goes well with this. In contrast to the neighboring room, both the wall covering from around 1830 and the curtains from 1695 to 1712 are part of the castle's original furnishings. A narrow spiral staircase next to the entrance door of this room leads to the mezzanine floor above . It is a relic of the house that stood at this point in the Middle Ages and was integrated into a more modern new building before 1780. The fabric of this new building is now in the ebony room , the adjoining drawing room and half of the library. They are grouped around the monumental main staircase, which was built for a total of ten years. Two different types of stone were used for its construction: oolithic limestone for the banisters and gray sandstone for the lavishly ornamented columns , posts and arches. The room is illuminated by an octagonal skylight with a window shaped like a flower.

The parade rooms on the second floor can be reached from the main staircase. There the visitor can see furniture, which mostly comes from the 1830s, as well as silk wallpaper in the Chinese style from the late 18th century. Visitors can also take the stairwell to get to today's castle chapel on the first floor. The chapel has floor tiles , which presumably originate from its previous building, the remains of which can be seen in the park today. The gallery was reserved for the noble family, while the servants on the ground floor took part in the services. The colorful chapel windows from around 1833 are attributed to David Evans of Shrewsbury. Also on the first floor is a bedroom called the Lower India Room , the name of which comes from its hand-painted fabric wallpaper made of Chinese silk . It probably dates from around 1800. The fireplace in this room is painted in color to match the basic color of the wallpaper.

The two dining rooms of the palace to the east can be reached via a colonnade separated from the Great Hall by columns . The larger of the two was used as a dining room for festive occasions and when guests were present, but was also intended as a gallery from the start . That is why numerous works from the castle's collection of paintings can be seen there. The room has a richly carved ceiling and a black marble fireplace made by Richard Westmacott . The stencil painting of the walls had been removed in the first quarter of the 20th century and was not restored until 1974. The smaller dining room, called the breakfast room, was used when only the owner family came together to eat. It owes its current appearance to a restoration between 1984 and 1985.

Castle park and garden

National Trust owned palace gardens and gardens take up 60 acres (24.3 hectares). This includes a landscaped garden with extensive lawns, wooded areas, a terrace garden and the former kitchen garden of the castle. The area called Penrhyn Park , which is completely surrounded by a seven- mile long wall, also includes extensive parkland, consisting of forest and meadows, owned by the Douglas-Pennant family. The majority of forests are used for forestry today. The Avon Ogwen flows through the castle park.

The basic structure of today's garden is based on the garden that was laid out in the late 18th century under Samuel Wyatt and changed and expanded in Victorian times . Nothing is left of the medieval garden. Access to the park is provided by a gate building called the Grand Lodge at the southern end of the area. This has a rich ornamentation and four watch towers with parapets. The arched gate can be locked by a double-leaf wooden door. A one kilometer long driveway leads uphill from the gate to the castle. On a meadow in the northeastern area of the area is a small pond that was created between 1889 and 1914 to attract wild ducks. The lawn to the west of the palace was traditionally used for symbolic tree planting. In addition to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, the Romanian Queen Elisabeth zu Wied also planted a tree there.

On the western edge of this meadow is the walled garden with three levels that are connected by stairs. It was conceived as a formal flower garden in the second half of the 19th century and thus continued an old tradition on Penrhyn, because there was a formal garden near the castle as early as 1768, but the majority of the new, spacious farm buildings gave way to the Wyatt renovation have to. Named after the garden, because it on three sides by a wall ( English wall is framed) brick. Earlier also stood at the fourth (western) side of the wall, but this was still in the 19th century or in transforming the local level to a bog garden ( English bog garden ) resigned. The course of the stream, which at the time bordered the swamp garden instead of the wall, has now dried up and can only be seen as a small depression in the terrain. The garden can be entered through an iron gate in the east corner. There are further entrances in the north-east and north-west wall. Sybil Hardinge, Lady Penrhyn, redesigned the garden in 1928. She retained the formal character of the garden, but changed its design. On the top level, she replaced the diamond-shaped flowerbeds with boxwood borders between the gravel paths with other geometric beds with water lily ponds and fountains . In addition, she had the central loggia built on this level. Although the Walled Garden was partially used as a vegetable garden during World War II, the current plant population on all three levels still dates from Lady Penrhyn's time. The middle terrace is designed with a lawn area with trees and bushes. An iron pergola overgrown with scarlet fuchsias stands on the wall on the third level . Other plants found in the garden are palm trees , ginkgos , climbing jasmine and kiwis .

The six acres (2.4 hectares) large former kitchen garden is no longer used as such. It is located north of the castle building and is surrounded on all sides by walls up to five meters high, some of which are overgrown with wild vines and ivy . In the second half of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, this garden, under the direction of head gardener Walter Speed, was known throughout the kingdom for the quality and variety of the fruits and vegetables grown. Today part of the garden is used by the Penrhyn-based forestry company as a tree nursery for conifers. Other parts serve as a private garden for the residents of the surrounding houses, for example the former laundry, a quarry stone building with a slate roof, which is now used as a house for three parties. The southern part of the kitchen garden is now the private garden of Penrhyn House , the former gardener's house of the castle on the southeast corner of the garden. Its numerous greenhouses have all disappeared today, because they were demolished after the Second World War, but the house for their heating system is still there. Since the kitchen garden no longer serves as a kitchen garden , no useful plants can be found there. Only a few old fruit trees, such as morello cherries , have stood the test of time.

The ruins of the former palace chapel stand between the kitchen garden and the walled garden . Only remnants of the northern and eastern walls of the small church are preserved. Each has a late 15th century window. Five plaques hanging on the walls from the 1920s to 1940s commemorate dogs from the owner family.

literature

- Cadw (Ed.): Penrhyn Castle. Description of the garden from the Cadw Parks and Gardens Register. Cadw, o. O o. J. ( PDF ; 182 kB).

- Sybilla Jane Flower: The stately homes of Britain. Personally introduced by the owners. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York 1982, ISBN 0-03-002843-4 , pp. 188-197.

- Mark Girouard: Historic Houses of Great Britain. Peerage Books, London 1984, ISBN 0-907408-83-4 , pp. 172-178.

- Linda Greeves: Houses of the National Trust. National Trust Books, London 2008, ISBN 978-19054-0066-9 , pp. 248-250.

- Douglas B. Hague: Penrhyn Castle . In: The Archaeological Journal. Volume 132, 1975, ISSN 0066-5983 , pp. 296-298.

- Douglas B. Hague: Penrhyn Castle . In: Caernarvonshire Historical Society (ed.): Transactions of the Caernarvonshire Historical Society. Volume 20, 1959, pp. 27-45.

- Richard Haslam: Penrhyn Castle, Gwynedd. Part 1 and 2. In: Country Life . No. 181 and 182, 1987, ISSN 0045-8856 , pp. 108-113 and 74-79.

- Christopher Hussey: Late Georgian, 1800-1840 (= English Country Houses. Volume 3). Antique Collectors' Club, Woodbridge 1988, ISBN 1-85149-032-9 , pp. 181-192.

- RCAHMW: An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments of Caernarvonshire. Volume 3: West. HMSO, London 1964, pp. 123-26 ( digitized version ).

- The National Trust (Ed.): Penrhyn Castle. The National Trust, Swindon 2004, ISBN 1-84359-116-2 .

Web links

- Entry for Penrhyn Castle on British Listed Buildings Online (English)

- Entry for Penrhyn Castle in the database of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales (RCAHMW )

- Entry for the castle gardens of Penrhyn Castle in the database of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales (RCAHMW )

- Virtual tour of Penrhyn Castle (English)

- Videos about the castle: Video1 , Video2 (English), Video 3

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Entry for Penrhyn Castle on British Listed Buildings Online , accessed May 28, 2015.

- ↑ a b c d Cadw: Penrhyn Castle. no year, p. 1.

- ↑ David Ross: Penrhyn Castle , accessed June 10, 2015.

- ^ M. Girouard: Historic Houses of Great Britain. 1984, p. 173.

- ^ The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 5.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Penrhyn Castle Papers at Bangor University ( Memento of the original from June 10, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Accessed May 29, 2015.

- ↑ a b c d C. Hussey: Late Georgian, 1800–1840. 1988, p. 181.

- ↑ RCAHMW: An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments of Caernarvonshire. 1964, p. 123.

- ↑ RCAHMW: An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments of Caernarvonshire. 1964, p. 126.

- ^ The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 6.

- ^ A b c The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 7.

- ^ The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 8.

- ^ The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 10.

- ↑ Cadw: Penrhyn Castle. no year, p. 4.

- ↑ a b c d Cadw: Penrhyn Castle. no year, p. 2.

- ^ The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 22.

- ↑ a b S. J. Flower: The stately homes of Britain. Personally introduced by the owners. 1982, p. 192.

- ^ A b The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 23.

- ^ A b c The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 42.

- ↑ 5 things you didnʼt know about stunning Penrhyn Castle , accessed June 8, 2015.

- ^ The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 29.

- ^ The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 57.

- ^ SJ Flower: The stately homes of Britain. Personally introduced by the owners. 1982, p. 195.

- ^ The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 71.

- ^ The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 34.

- ↑ Cadw: Penrhyn Castle. no year, p. 8.

- ^ The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 35.

- ^ The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 88.

- ^ A b The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 27.

- ↑ a b C. Hussey: Late Georgian, 1800-1840. 1988, p. 189.

- ↑ a b Cadw: Penrhyn Castle. no year, p. 10.

- ^ C. Hussey: Late Georgian, 1800-1840. 1988, p. 188.

- ↑ Entry for the ice tower of Penrhyn Castle in the database of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales (RCAHMW) ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Accessed June 9, 2015.

- ^ A b The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 74.

- ^ The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 26.

- ^ M. Girouard: Historic Houses of Great Britain. 1984, p. 178.

- ^ A b The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 45.

- ^ Mark Purcell: Some Whiffs of Orientalism in North Wales. In: The National Trust (Ed.): Arts, Buildings & Collections Bulletin. April 2011, p. 5 ( PDF ( Memento of the original from June 10, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this note .; 1 MB ).

- ^ The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 48.

- ^ The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 51.

- ↑ Penrhyn Castle on snowdoniaguide.com , accessed June 10, 2015.

- ^ The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 60.

- ^ The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 58.

- ^ A b The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 62.

- ^ The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 66.

- ↑ Penrhyn Castle on the National Trust website , accessed June 9, 2015.

- ↑ Country Homes: Penrhyn Castle. In: Country Life Illustrated. No. 40, 1897, ISSN 0045-8856 , p. 378.

- ↑ Ruprecht Rümler: The gardens of castles in the UK. In: Castles and Palaces. Vol. 29, No. 2, 1988, ISSN 0007-6201 , p. 97.

- ^ The National Trust: Penrhyn Castle. 2004, p. 82.

- ↑ Cadw: Penrhyn Castle. n.d., p. 12.

- ↑ Cadw: Penrhyn Castle. n.d., p. 13.

- ↑ Cadw: Penrhyn Castle. undated, p. 5.

- ↑ Cadw: Penrhyn Castle. no year, p. 3.

- ↑ Cadw: Penrhyn Castle. no year, p. 14.

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales (RCAHMW): An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments of Caernarvonshire. Volume 1: East. HMSO, London 1956, p. 105 ( digitized version ).

Coordinates: 53 ° 13 '33 " N , 4 ° 5' 41" W.