Battle of Bouvines

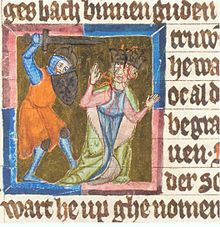

Depiction of the equestrian battle between King Philip II Augustus and Emperor Otto IV in Bouvines. Late medieval miniature from the Grandes Chroniques de France (Paris Bibliothèque nationale de France, Ms. fr. 2813, fol. 253v).

| date | July 27, 1214 |

|---|---|

| place | Southeast of Lille, France; at Bouvines in Flanders |

| output | French victory |

| consequences | Philip thwarted England's hopes for reconquests north of the Loire. Otto IV lost his empire to the Staufer Friedrich II . |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

English , Guelphs, Flemings |

|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 7,000-8,000 men | 8,000-9,000 men |

| losses | |

|

less than 1,000 men, only a few knights |

probably more than 1,000, including 170 knights; numerous prisoners |

The Battle of Bouvines took place on July 27, 1214 near the village of Bouvines between Lille and Tournai . At that time the place belonged to the county of Flanders , but is now located in the French department of the North of the Hauts-de-France region .

In this battle an army of the French King Philip II August and an Anglo- Welf army under the leadership of Emperor Otto IV faced each other. It ended with a victory for Philip II.

causes

France versus Plantagenet

The conflict between the King of France and the King of England was less of a national conflict between France and England than of the French kingship ( Capetians ) and its vassals from the House of Plantagenet . Its cause is ultimately the collapse of the Carolingian kingship and the change of dynasty to the Capetians from the 9th to 10th centuries. During this time, the West Franconian empire split into a large number of de facto sovereign feudal principalities, among which the kings as lords of the Île-de-France were just one of many. Their superior position to the princes was only supported by the feudal state idea , in that the king stood at the top of the feudal pyramid and the princes were subject to him as feudal vassals. In fact, however, many of these princes were so powerful that they at most formally recognized the sovereignty of the kings and ultimately pursued an independent policy, which in case of doubt could also be directed against the king himself. This situation was exacerbated when in 1066 the Duke of Normandy undertook his conquest of Britain and was crowned King of England. The resulting "Anglo-Norman Empire" questioned the continued cohesion of the French feudal association for the first time, as Normandy, one of its largest principalities, threatened to slip away from it.

This situation came to a head in the middle of the 12th century when the Plantagenets from Anjou took over the " Anglo-Norman Empire " and expanded it into the so-called " Angevin Empire " with the acquisition of the Principality of Aquitaine . They thus ruled the entire west and south of France and at the same time, as kings of England, were the overlords of the British island, while the French kingship threatened to collapse in their shadow. King Philip II of France opposed this threatening development and tried to smash the power of the Plantagenets by trying to use their intra-dynastic conflicts to his advantage. He was always militarily inferior to his main rival Richard the Lionheart , and it wasn't until his unexpected death in 1199 that the decisive turning point was brought about. Richard's younger brother, Johann Ohneland , failed to maintain his authority over his own vassals. At the same time, Philip II was able to use feudal means against him after Johann had violated the provisions of French feudal law on several occasions. In 1202 King Philip II declared it forfeited by a court ruling for all of its territories in France and successfully implemented this decision militarily by 1204.

The Angevin empire was smashed, and at the same time Philip II was able to expand the French kingship into the sole legislative and ruling power in his kingdom. This development was called into question again with the events leading up to the battle in 1214.

The German controversy for the throne

In the German throne controversy triggered by the double election of Philip of Swabia and Otto IV , all the decisive powers of Western Europe were involved. The Plantagenet Johann Ohneland was seen as an ally of his Guelph nephew Otto von Braunschweig, through whose kingship in Germany he was able to embrace France. This in turn made King Philip II an ally of his Hohenstaufen namesake, with whose help he hoped to avoid being clasped. Despite the pope's preference for the Guelph, the Franco-Staufer cause seemed to prevail after Philip of Swabia's several military successes, until the Staufer was assassinated in Bamberg in 1208 . That seemed to be the decision. Several Hohenstaufen partisans in Germany now recognized Otto IV as the rightful king. He moved to Rome in 1209 to receive the imperial crown from the Pope.

However, the subsequent actions of Emperor Otto IV led to another change in the situation, as he conquered southern Italy immediately after his coronation and thus resumed the Staufer Italian policy. This forced Pope Innocent III. to rethink his attitude towards the Guelph, whom he excommunicated in 1210. The Pope made contact with King Philip II of France, who took the opportunity to escape the threatening embrace of his kingdom. Together they supported the refuse movements of Staufer-minded princes in Germany who elected the young Sicilian King Friedrich II von Hohenstaufen as king in Nuremberg in 1211 . Emperor Otto IV then returned to Germany to restore his authority. But only a year later Friedrich himself set foot on German soil in Constance , and in November 1212 the Franco-Staufer alliance was renewed in Vaucouleurs .

In April 1213, King Philip II decided to take offensive action against John Ohneland, who had been banned by the Pope, and gathered an army in Boulogne to risk an invasion of England. However, the attack had to be canceled after John submitted to the Pope. Instead, Philip moved against Flanders , whose Count Ferrand and Count Rainald von Boulogne ( Renaud de Dammartin ) had risen against him. Both counts were forced to flee to England, where they paid homage to Johann Ohneland in the spring of 1214 and thus committed felony (high treason) in relation to the King of France . Johann Ohneland, on the other hand, saw in this apostasy an opportunity to regain his lost possessions on the mainland through an offensive action against Philip II.

The way to Bouvines

With his nephew, Emperor Otto IV, Johann arranged a combined attack on France, which was to finally destroy the Capetian kingdom and thus bring the decision in France and Germany in favor of their cause. Their original plan was a two-way attack. In the spring Johann landed with an army on the coast of the Saintonge , marched through the Poitou , conquered the Breton Nantes and then advanced into the Anjou . This was intended to lure Philip away from Paris to the southwest in order to enable Otto to invade the northeast (Flanders) and to conquer Paris. The plan seemed to be successful at first, because Philip rushed to meet Johann's invasion in February 1214. Otto's army was not ready in time; Philip learned of Otto's impending invasion, left his army in the care of his son Prince Ludwig , returned to Paris and organized the formation of a second army with which he wanted to march against the emperor.

At the beginning of July 1214 Otto had finally concentrated his army in the imperial palace of Aachen and began his march to Flanders. On July 12th he reached Nivelles , where on July 21st he was joined by the contingents of the Counts of Flanders and Boulogne, as well as an English contingent under the Count of Salisbury . At this time, however, Johann had already suffered a heavy defeat against Prince Ludwig at Roche-aux-Moines on July 2, 1214 and had to retreat to the south, where he was prevented from advancing further.

On July 23rd Philip had finished his armor and started his march to Flanders from Péronne . On July 25, he crossed the bridge over the Marque near Bouvines and camped on its right bank. Philip was already on enemy territory, because the greater part of Flanders and his count were against him. On July 26th Philipp was able to move into Tournai after a short fight . Emperor Otto, who had meanwhile reached Valenciennes , became aware of the French army and, on the morning of July 27th, reached Mortagne, only six miles south of Tournai . Philip wanted to go over to the attack immediately, but was changed by his advisors to a retreat to Lille , which should remain open to them the way to the French heartland.

In order to still be able to reach the refuge of Lille, Philip would have had to lead his army a second time over the Bouvines Bridge, as it was the only way for miles to cross the wide marshy river valley of the Marque, which separates two plateaus. Philip found himself in a precarious position that day, as his infantry were already on the left bank of the Marque, but not the cavalry, which put him in a disadvantageous position in the event of a surprise attack. Then the Vice Count of Melun and the Bishop of Senlis with a division of light cavalry and crossbowmen set off from the army on a reconnaissance campaign. About three miles away they spotted the emperor's army, whereupon the bishop hurriedly warned the king of the danger. The majority of the barons did not let that change their mind, however, because they believed the emperor would move to Tournai first. In the meantime, however, the emperor had reached the position of Vice Count von Melun, who immediately threw himself into the fight and thereby stopped Otto's further advance. Due to the noise of the fighting, the rest of the French army was now convinced of the imminent danger. Philip ordered his infantry to quickly turn back and prepare the army for battle. Otto, who was thus deprived of the element of surprise, had his army stop and take up line-up over the entire plain between Bouvines and Tournai.

At noon on July 27, 1214, the two armies faced each other on a 1.5 km wide front. It was a Sunday, a sacred church convention, on which the “truce of God” (Sunday peace) had been in effect for almost 200 years. The shedding of blood was prohibited on such a day, as was sexual intercourse and trafficking. In such cases, clergy dignitaries were empowered to pronounce excommunication against the peace breakers. The English chronicler Roger of Wendover reported that the Earl of Boulogne advised his allies not to fight that day, lest they be guilty of defiling the day with human murder and bloodshed. The emperor is said to have agreed with him, but ultimately allowed himself to be carried away by the blasphemous Hugues de Boves .

March

The King of France led around 1,300 knights and as many mounted servants, as well as a little more than 4,000 fighters on foot. The Roman-German emperor's cavalry was only slightly stronger, but he had a clear preponderance of foot soldiers. A total of about 4,000 mounted men and about 12,000 foot soldiers stood in the field between Bouvines and Tournai.

The army of the French king

The composition of the knighthood led by the King of France was regionally homogeneous. The knights came mainly from the northern French regions of Picardy , Laonnois , Burgundy and Champagne . The majority of the knighthood of the Île-de-France was on the Albigensian Crusade, which was taking place at the same time . Normandy probably only made a small contingent, only two knights were named. This province belonged to the Plantagenets until 1204, which is why little trust was placed in the allegiance of their knights. The Knights of Anjou and Touraine were still involved with Prince Ludwig in the battles against Johann Ohneland, sometimes even allied with him or adopting a wait-and-see neutral stance.

The infantry was made up of the militias of 16 communes in Picardy and Laonnois, 15 of which are known by name: Noyon , Amiens , Soissons , Beauvais , Arras , Montdidier , Montreuil , Hesdin , Corbie , Roye , Compiègne , Bruyères, Cerny , Grandelain and Vailly.

The army of the Roman-German emperor

Emperor Otto IV led mainly Saxon and Lower Lorraine knights, corresponding to the regions of the empire from which his most loyal followers came. A large part of his army was provided by his allies. The Count of Flanders, who had defected the French king, led Flemish knights and communal militias into the field. He was also joined by a number of knights from the Artois , a former Flemish province that had fallen to the French Crown Prince after a few inheritance disputes. Other renegade French knights and Brabanzon mercenaries fought under Rainald I. von Dammartin . The Earl of Salisbury led a contingent of English knights.

equipment

The armies on both sides were composed of cavalry contingents as well as large detachments of foot soldiers. The latter were clearly over-represented on both sides, but due to their light equipment they were of little military value. The events on the field of Bouvines were determined by the armored cavalry, which is why this battle is one of the classic knight battles of the Middle Ages.

The quality of the equipment differed depending on the level and ability of the mounted fighters, because not every mounted man at Bouvines was a knight. Especially at the turn of the 12th to the 13th century, when knighthood began to establish itself in a stable social class, to whose preservation an appropriate financial basis was necessary, fewer and fewer members of the small nobility could afford the necessary conditions for being awarded the sword leadership and there went before so when lesser nobility to go into battle. The costly developments in weapons technology of this time have additionally promoted this change in the social position of the knight. The king's standard-bearer, Galon de Montigny, is said to have been such a poor knight that he had to pledge all of his possessions in order to be able to afford armor suitable for the battle. The mail shirt (Brünne), made of iron rings or plates, was the most common protection of the cavalry. The wealthy knights and barons at Bouvines were already able to protect themselves with metal arm and trousers that reached over wrists and ankles. The head was protected by the cylindrically shaped helmet , which completely covered the face and only had small openings for sight and breathing. On the other hand, noblemen and less wealthy knights still wore outdated nasal helmets . Since the identity of most of the knights could hardly be made out on the battlefield, the coat of arms served the knight for his own recognition as well as for the opponent. Applied to light fabric, the coat of arms was stretched over a V-shaped shield , and it was not uncommon for it to be damaged or even torn completely in the first collision with the enemy. The armament of the knights consisted of a sword , knife and mace for close combat in addition to the lance as a thrust weapon. The Bishop of Beauvais is said to have only fought with a club, as his clergy forbade him to carry knightly weapons.

The infantry hardly had adequate protection. It wore simple leather skirts, high gaiters and iron caps at best. Despite its minor importance for the course of the battle, the common fighter on foot therefore made up the bulk of the fallen. The only significant weapon he possessed were the hook-and- tipped pikes used to pull the knights from their horses. These weapons were therefore regarded as unknightly, accordingly they were only used by the enemy in the battle report described by the chaplain of the French king, although the use of such weapons on the French side is likely. A later German chronicle from the Swabian Abbey of Ursberg only accused the French of using these weapons.

Order of battle

The French army was formed in the usual three slaughterhouses: in the center stood the king with the lily banner and the knights of his household, whose unofficial leader was the battle-hardened Guillaume des Barres ( La Barrois ). With the Count von Bar, there was only one representative of the high nobility at his side, because he was still too young (that is, unmarried). The knights stood here in the front row, while the foot troops of the communal militias with the Oriflamme were positioned behind them. The left wing, made up of the few knights from Île-de-France and Normandy led by their royal cousin Count Robert II of Dreux . On the right wing stood the knights from Burgundy and Champagne under Duke Odo III. of Burgundy .

The army of the Anglo-Guelph allies was also formed: in the center, Emperor Otto with his Saxon knights and foot servants, plus the contingents of the Lower Lorraine princes. On his left wing stood the Flemish knights and militiamen under their count. On the right English and French knights under the Counts of Boulogne and Salisbury, plus the Brabant Zones.

From the traditions, account books, lists of prisoners and the lists of those who stood as guarantors for ransom money, about 300 people who took part in this battle could be identified by name. With four exceptions, all were of at least knightly status and only about a dozen appear in the traditions of contemporary chroniclers for the course of the battle in a greater light.

| position | France | Imperial | position | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| left wing |

|

|

right wing | |

| center |

|

|

center | |

| right wing |

|

|

left wing | |

| Other participants | ||||

|

|

|

|||

The battle

Opening the fight

The fight began with an "unsporting behavior" of the French on their right wing. Without the knowledge of the king, the bishop of Senlis led 150 mounted servants against the ranks of Flemings who felt it was unworthy not to be challenged by knights and therefore initially held their positions. The attack had no particular effect, but after it had been repulsed, as expected, some Flemish knights rushed into hand-to-hand combat with French knights. Eustache de Maldeghem was the first knight of this battle to be killed, Gautier de Ghistelles and Jean Buridan the first to be captured by the French.

Then the open fight began after the entire right wing of the French had rushed into the fight. The horse under the saddle was killed for the Duke of Burgundy, he fought on with a new one. Other knights, who did the same, continued the fight on foot.

Attack by French infantry

In the center the fight was started by the French infantry, who repositioned themselves from behind the line in front of the row of the king and then began to advance against the row of the emperor. However, the common fighters were quickly repulsed by the Saxon knights of the emperor and with great losses to the line of the king. When the royal knights recognized the danger for their master, they formed a protective wall in front of him under the guidance of Guillaume des Barres to fend off the counterattack of the Germans ( furor Teutonicus ). Nevertheless, the Saxon infantry managed to find loopholes in the scuffle that was now developing and penetrated as far as King Philip. With lances and pickaxes, they managed to pull the king off his horse. But before they could kill him, several royal knights intervened and killed the Saxons.

After King Philip was back in the saddle, a battle developed between his knights and those of the emperor. Étienne de Longchamps was killed next to the king when a knife pierced his head through the slits in his helmet.

The king as a goal

The strategy of the emperor and his allies was to direct the force of their attack directly on King Philip in order to force a quick decision. According to Briton, they also accepted the king's death. Count Rainald von Boulogne accordingly oriented the thrust of his wing towards the center of the enemy. He managed to get as far as the king and threaten him, but was thrown back by a royal knight. Another action by Rainald against the king failed because of his counterpart, the Count of Dreux, who pushed his wing between him and the royal center. The Count of Boulogne then formed a double wall with his footmen and mercenaries, withdrawing several times to recover from the exertions of the battle, only to be able to throw himself freshly into battle afterwards.

The Count of Flanders is captured

Following the Count of Boulogne, Count Ferrand of Flanders also tried to throw his wing directly at the French center, but was ultimately prevented from doing so by the Duke of Burgundy. After the fight on this wing was for some time mainly characterized by duels between the knights, the Duke of Burgundy let his knights attack the Count of Flanders, whose immediate entourage was increasingly worn out. The Duke was almost killed by Arnaud d'Audenarde with a targeted knife cut into the viewing slits of his helmet.

Ultimately, the knights from Burgundy and Champagne won the upper hand. The Marshal of the Count of Flanders, Hellin de Wavrin, was captured, killed by the brothers of the same name, de Gavre the Younger. Count Ferrand himself was wounded several times and ultimately had to surrender from exhaustion. The Flemish knights then fled or oriented themselves to the battles in the center. The left wing of the imperial army gradually dissolved.

Decision in the center

The knights of King Philip managed to fight their way up to the rank of the emperor, thereby compelling him to take part in the battle. The knight Pierre de Mauvoisin was able to seize the reins of the emperor, but failed to pull him out of the fray. Finally Girard la Truie ( the pig ) stabbed Otto in the chest with a knife. The blow was intercepted by the emperor's armor, however, and la Truie tried a second. However, it hit the eye of the rearing horse of the emperor, which went through and then collapsed dead. When Otto tried to get on his second horse, he was harassed by Guillaume des Barres, who tried to grab his neck twice. His Saxon knights, however, were able to protect him from the enemy and throw La Barrois from his horse.

In the meantime, the knights Barthélemy de Roye and Guillaume de Garlande had decided to pull King Philip out of the battle to take him to a safe place in the back rows. Surrounded by Saxon warriors, Guillaume des Barres was rescued from his predicament by Thomas de Saint-Valéry, who stormed the battlefield with 50 knights.

Although Emperor Otto was back on horseback and his knights continued to hold the ranks, he decided to leave the battlefield. Medieval chroniclers rated this act differently. While almost all French reports unanimously spoke of escape, this was either kept secret in English and German chronicles, especially from the Saxon-Welf area, or presented as a forced retreat after the French had waged a devious and unknightly fight in clearly superior numbers . Both the reports of the victors and the vanquished are tendentious, but the emperor seems to have actually been in mortal danger when he left the battlefield. Otto was brought to safety by his body knights. They left behind the golden supply wagon, which was destroyed by the French, and the standard with the imperial eagle, which was captured with broken wings.

Last fights

On the side of the Imperialists, the Count of Boulogne held the longest fighting on his right wing. When the emperor and most of his knights had already fled, he withdrew with six remaining knights into his ring wall, which he defended like a castle. But in the end his men were killed by the overwhelming force of the French, he himself was buried under the body of his horse after it had been fatally wounded. A French servant tore his helmet off his head and wounded his face. The Flemish knight Arnaud d'Audenarde tried to free him from his position, but was captured. Several French knights such as Jean de Nesle fought over the capture of the Count of Boulogne, but he finally surrendered to the Bishop of Senlis, who had meanwhile reached the point. The Earl of Salisbury, a half-brother of King John Ohneland, surrendered to the Bishop of Beauvais.

After the emperor's escape, only a division of the Brabanzonen remained on the battlefield, forming a narrow wall. King Philip commissioned Thomas de Saint-Valéry and his 50 knights to fight them, which quickly succeeded without suffering further losses.

After the battle

The French army marched back to Paris on the evening of July 27th. In the battle it could capture five counts and at least twenty-five banner masters of the enemy. Among them were the Counts Rainald von Boulogne and Ferrand von Flanders, who had committed felony to the King of France with their homage to John Ohneland . According to the legal norms in force at that time, King Philip II could have sentenced them to death and executed them, but he pardoned them and only sentenced them to indefinite imprisonment, which they had to spend in chains. The English Earl of Salisbury was given by the Bishop of Beauvais to the Earl of Dreux, so that he could exchange him with Johann Ohneland for his son Robert Gasteblé , who had been captured in Nantes. The rest of the captured knights had to buy their way out by paying ransom.

According to Wilhelm Brito's report, the march back turned out to be a single triumphal procession. In every village the army passed, it was solemnly received by the population and the king cheered. The captured Counts of Boulogne and Flanders were treated with abuse by the people. To commemorate the victory, the king founded the Abbaye de la Victoire near Senlis , to which he immediately donated part of the booty. He notarized that everlasting thanks for victory should be sung in the abbey. At the gates of Paris, the army was received by representatives of the citizenry, the clergy and the student body and then led into the city.

consequences

Staufer and Germany

After the defeat, Emperor Otto IV fled to Cologne and then retired to his home in Braunschweig . There he died in May 1218, lonely and largely deprived of power, because already after the Battle of Bouvines the majority of German sovereigns recognized the Hohenstaufen Frederick II as their king. After Otto IV's death, the Guelf party did not raise any further pretenders and also recognized the Staufer. The German controversy for the throne was thus decided in their favor.

King Frederick II, however, who was also crowned emperor in Rome in 1220, viewed his native Sicilian kingdom as the mainstay of his power and therefore saw Italy as the focus of his politics. In order to accommodate the German princes who had supported him, but also to take account of the circumstances of his political action, he renounced important rulership rights in Germany in the years to come. In the confoederatio cum principibus ecclesiasticis (alliance with the princes of the church) of 1220, he first assigned the clergymen and in the statutum in favorem principum (statute in favor of the princes) of 1232 to the secular lords important rules (i.e. royal rights), such as striking of coins or the jurisdiction. If Frederick's father, Emperor Heinrich VI., Was still striving to establish a strong hereditary kingship in Germany, this actually meant a weakening of the central royal power in favor of the sovereign power of the German princes. The German federalism , which shapes the constitution of this country to this day, found its beginning.

Plantagenets and England

After the news of the defeat of his nephew had reached him, King Johann Ohneland asked King Philip II to start negotiations on an armistice through the intermediary of the Vice Count of Thouars . Johann was stuck at Roche-aux-Moines in the Poitou since his own defeat and was constantly persecuted by Prince Ludwig. The emperor's defeat took away his last chance to end the campaign against France successfully. On September 18, 1214, in the armistice agreed in Chinon , he had to confirm the provisions of the Thouars armistice, which had already been concluded in 1204 , according to which he had to renounce all French territories of his family north of the Loire.

Then he traveled back to England. There he was confronted with a widespread revolt by his barons, which had been sparked by the material and personal burdens of their class for the dynastic policy of their king in France. In 1215, Johann at Runnymede was forced to sign the Magna Carta Liberatum (the great charter of freedom), in which he had to give the barons far-reaching freedoms and political say.

The Battle of Bouvines not only gave Johann the last opportunity to recapture the family empire ( Angevin Empire ) that had been defeated in 1204 , it also set in motion a constitutional development that would influence the further course of English history. In addition to the Anglo-Norman kingship founded by William the Conqueror in 1066, the higher authority of the assembly of the crown vassals, to which the king had to commit himself to present his policy for discussion, now appeared. This laid the foundations of English parliamentarianism , which not least had a significant influence on America and mainland Europe.

Another consequence of the battle, also decisive for England, was the gradual development of an island national consciousness. As a result of the battle, the island's aristocracy, who mainly came from France, and not least the royal family themselves, lost their families' ancestral estates and thus their ideal ties to the homeland of their ancestors. They were forced to integrate into the Anglo-Saxon population, which they had ruled for almost 150 years, and adopted an independent English mentality.

Capetians and France

In France, the Battle of Bouvines favored an opposite development. Even before the battle, King Philip II was engaged throughout his reign to enforce the power of the crown against the great vassals of his kingdom. With the smashing of the Angevin Empire in 1204, he finally helped this endeavor to break through. With the victory at Bouvines, King Philip defended what he had achieved up to then and repelled the last serious attempt by the Plantagenets to recapture their lost family empire. The following disputes Johann Ohneland and his son, Heinrich III. , with their English barons undermined any further attempt. But it was not until the Peace of Paris in 1259 that Henry III. willing to contractually recognize the facts created at Bouvines.

The victory at Bouvines allowed Philip II and his successors to establish a royal supreme power over all regions of their kingdom, which with the crown had its only valid legal and political basis of legitimation. The centralism still prevailing in France today was thus helped to achieve a decisive breakthrough. From then on the power of the feudal princes was gradually restricted; even in Philip's time none of the dukes or counts was powerful enough to be able to afford enmity against the crown. The high medieval feudalism, which had shaped France for almost 300 years, came to an end soon and in the further course of the 13th century was increasingly to give way to a monarchical idea that already had an early absolutist character under Philip IV the Handsome (1285-1314) .

At the same time, the battle marked a fundamental change in the previous relationship between France and the Roman-German Empire. The idea of recognizing the highest secular authority of the Christian world in the Roman emperor was moved further and further away. Instead, the King of France now claimed a position equal to that of the Roman Emperor with regard to the dynastic and legal inheritance of the Carolingians . The very fact that the German controversy for the throne was decided by French weapons reinforced Philip II's attitude. He made this clear symbolically by sending the captured standard of the imperial eagle with its broken wings to his ally Friedrich II. A clergyman from the Petersberg monastery near Halle reported this scene with the comment: "Since that time, the name of the Germans was disregarded by the Gauls." But even before the battle, Philip, with the confirmation of the Pope, had a claim to supremacy by the Roman Empire over France denied (see: Decretals Per Venerabilem ).

swell

There are a total of four contemporary accounts of the battle. The largest is that of the French king's chaplain, Wilhelm Brito , who himself was an eyewitness to the battle. Brito wrote two descriptions of the battle, once in the Gesta Philippi Augusti des Rigord , which he continued, and a second time in his own Verschronik Philippidos , which he began immediately after the battle. However, only the report of the Gesta is regarded by the specialist science (see Duby) as an objective description of the events, while the Philippide serves more to glorify King Philip II and takes on clearly exaggerated and legendary features.

Also shortly after the battle, the monks of Marchiennes Abbey put the events together in a report ( De Pugna Bovinis. ). It was published in the 19th century by Georg Waitz in the Monumenta Germaniae Historica . There is also a Flandria Generosa from the Cistercian Abbey of Clairmarais near Saint-Omer , which concludes with the battle, as well as a history of the bishops of Liège written in 1250 by the monk Aegidius from Orval Abbey , which contains a report of the battle, based on an original from 1219.

The report by the anonymous chronicler of Béthune is suitable for supplementing and correcting Brito's account . He was in the service of Baron Robert VII. De Béthune , who narrowly escaped captivity in the battle, and began on his behalf in 1220 with the writing of a royal chronicle ( Chronique des rois de France ), which dates to 1217 . The Anonymous described the course of the battle mainly from the perspective of the Flemish knights. The most important English account of the battle was provided by the monk Roger von Wendover in his world history, Flores historiarum , written between 1219 and 1225 .

The earliest known written note on the battle was left by Queen Ingeborg , the outcast wife of King Philip. In the Ingeborg Psalter she wrote in a marginal note on August 6, 1214:

“Sexto kalendas augusti, anno Domini M ° CC ° quarto decimo, veinqui Phelippe, li rois de France, en bataille, le roi Othon et le conte de Flandres et le conte de Boloigrie et plusors autres barons."

"[...] Philip, the King of France, won the victory over King Otto and the Count of Flanders and the Count of Boulogne and several barons in a battle."

Usually only intercessions and thanksgiving were noted in a psalter.

reception

Shortly after the battle, this event began to be of great national importance in the perception of French contemporaries. Contributing to this was the participation of the northern French communal militias in the struggle and the resulting feeling among ordinary citizens that they had as much part in the defense of the kingdom as the princes and knights. The Sunday of Bouvines is today in the national memory of the French as one of the “Trente journées qui ont fait la France”, one of the thirty days on which France was founded, and thus one of the fixed points in the emergence of a French national consciousness.

The myth

A national myth quickly developed around the battle . It all started with the writing of La Philippide by royal chaplain Wilhelm Brito. With this hymn of praise for the reign of King Philip II August Brito wanted to set a literary monument for himself and his king. The work, begun immediately after the battle and completed in 1224, comprises 12 chants and nearly 10,000 verses. The battle of Bouvines alone takes up the last three cantos and, as a divine judgment with the liturgy of a judicial duel, forms the climax of an eternal crusade in which good prevails over evil. Brito lets the king appear as the eternal avenger of God, as the helper of the crusaders and the church, while at the same time the supporters of the heretics (Johann Ohneland) and the banished emissaries of the devil (Emperor Otto IV) are condemned.

In addition to exaggerating the king, Brito was the first author to undertake a comprehensive transfiguration of the French people, whom he wanted to see clearly separated from other peoples in terms of their ethos and descent and elevated above them. As early as the 7th century, Fredegar gave the French a descent from the Trojans . Brito took up this by letting King Philip, dressed in the robes of Aeneas , speak to the "descendants of the Trojans" on the day of the battle. In the battle, the “sons of Gaul” fighting nobly on horseback face the dark “Teutons” who fight like servants on foot. Brito also no longer wanted to count the Flemings, who at least belonged to the French kingdom, to the French, as they finally speak a German dialect. He referred to the knights of King Johann Ohneland as "sons of England", provided that they actually came from the island. But those who came from the French mainland, from the Angevin country complex, were also "Gauls" for him. In the enemy's camp, Brito only recognized the Count of Boulogne as the "child of French parents", since he was also from France and was lured from the right path by evil spirits. The battle itself finally proved that the Germans "are really inferior to the French, ... and that French courage to fight always defeats German violence." The author does not let the king fight for a dynastic inheritance or for the mere overthrow of heretics, but rather for the fate of an entire nation. Accordingly, victory is not celebrated as a result of an act by a ruler like Caesar or a city like Rome , but by the entire “body of the kingdom”. This means that in every castle, in every city and in all regions of the country, including in the Angevin parts that were still held by the Plantagenets, the population celebrated the victory as an act of arms by their people. In this description Brito for a brief moment also dropped every class barrier that divided the social order of the Middle Ages into fighters, peasants and prayers, in which he lets them all celebrate in "scarlet splendor" ( purple ).

Bouvines remained vividly remembered in France throughout the 13th century. New descriptions of the battle were written, which, even more than the Philippid did, convey the true course of events in a distorted and exaggerated manner. For example, the monk Richer von Senones reported in the second half of the century that Emperor Otto IV had carried over 25,000 knights and 80,000 foot servants with him, ultimately losing 30,000 men through battle and captivity. On the French side, on the other hand, only a knight and a mounted servant would have lost their lives. Furthermore, the victory was solely due to the miraculous power of the Oriflamme and its bearer, Galon de Montigny. According to the Franciscan brother Thomas from Tuscany, who wrote in 1278, the French fought against a tenfold superiority. The anonymous Ménestrel of Reims and Philippe Mouskes wrote similarly embellished stories .

Before 1250, 42 verses in French describing the battle were carved in the arch of the Porte Sainte-Nicolas in Arras. The gate is thus one of the first public memorials to refer to the battle. Before the verses were completely weathered in the 17th century, they were partially copied once in 1611 by the local pastor Ferry de Locre and once in full by the lawyer Antoine de Mol in 1616. King Louis IX the saint had the church of Sainte-Catherine-du-Val-des-Écoliers built in Paris , in memory of his father, his grandfather and the victory they both had at Bouvines.

The battle outside France

In England, despite the associated defeat of King John Ohneland, the battle was largely viewed positively. The mostly religious chroniclers recognized Philip's victory here, which is not surprising since their own king had been banned a few years earlier and had forcibly appropriated the monastery and church treasures of his country. In a concluding overview, Matthäus Paris , who had continued Wendover's work with his Chronica Majora , described the battle as one of the few “notable events” that, as far as he knew, had occurred in the last fifty years. However, some English reports tried to belittle the French victory. The story of William Marschall ( L'Histoire de Guillaume le Maréchal ), for example, emphasized the cunning and cowardice of the French and presented the Count of Salisbury as the only real hero of the battle.

In Germany most of the comments on the battle appeared in the Lorraine region, which was influenced by the events in neighboring France and Flanders due to its border location at the time. In addition, several reports appeared in the Saxon area, the center of Emperor Otto's power, which naturally provide a version of the events that is contrary to the French reports. So there is nothing to be learned about an escape of the emperor. Also, the emperor and his knights would have had to fight honorable and outnumbered against cunning French who only won the victory because they had set a trap for the emperor. From the fragments of a chronicle of the princes of Braunschweig it can be deduced that Emperor Otto was a true prince of peace who was challenged to battle by the French against his will.

In Italy the battle was mentioned in only four contemporary accounts, including once by the monks of Montecassino , who had dealt with the politics of Emperor Frederick II. In France south of the Loire it was mentioned only three times, in Catalonia only once in a chronicle of the Abbey of Ripoll . The attention of the people of these regions was rather the battles of Las Navas de Tolosa and Muret .

memory

With the start of the Hundred Years War in the first half of the 14th century, memories of the Battle of Bouvines gradually began to fade. The victory of their king over an emperor remained in the general consciousness of the French people, but the current defeats at Crécy and Poitiers brought a new enemy image to the fore with the English, while good relations were maintained with the German emperors. Furthermore, the fame of Bouvines from the veneration of saints King Louis IX. and finally dwarfed by the great triumphs of Bertrand du Guesclin and Joan of Arc over the English. In the 17th century, Bouvines attracted little interest from historians. Mézeray described the battle on nine pages in his work published in 1643; Guillaume Marcel sketched it in broad outline in 1686. Both are loosely based on Brito's report from the Gesta .

It was not until the July Monarchy (1830–1848) that the memory of Bouvines found a real revival. Determined by the emerging romanticism and by the fact that the advocates of the bourgeois kingdom were able to draw numerous arguments from the battle reports. Guizot described King Philip II as the first French king who gave the monarchy the "character of an understanding benevolent, aimed at improving social conditions". He later emphasized the importance of the communal militias for the battle, which, with a "force far superior to the feudal army", made victory a "work of the king and the people" as a result of the "unification of all classes". For the anti-clerical Michelet, on the other hand, the battle “did not seem to have been a remarkable affair”, since it only strengthened the alliance between throne and altar. For him it was a victory of bigotry and manorial oppression. Before these two, however, Augustin Thierry , with whom Guizot largely agreed, had called for the traditional testimonies to be subjected to a systematic criticism in order to separate historical distortions from chronological truth. In 1845 an archaeological congress began to draw up plans for the construction of a monument at the slaughter site. The six-meter-high obelisk , which is still standing today, was erected in 1863 and only contains the number 1214 as an inscription. The aim was to take into account the well-being of the Flemings living in France, since they were seen as the real losers of the battle even more than the Germans.

This changed after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71. Once again the German Kaiser became the main enemy of the French and the commemoration of the Battle of Bouvines was taken over by nationalist propaganda, in which it was seen as the second manifestation of French patriotism after the Battle of Alesia . In the school books of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the battle was described as a victory of the French people over the feudal system, which until then had had disastrous influences on national consciousness. Ernest Lavisse described the battle in his Cours published in 1894 as the "first national victory". In 1901 Blanchet and Périard reaffirmed the decisive role of the municipalities in the victory and in 1903 Calvet stated that Bouvines was "the first victory over the Germans". In Germany itself, the battle was used as an example of Franco-German hereditary enmity .

1903 ordered Pope Leo XIII. the transfer of relics of Saints Fulgentius and Saturnia to the church of Bouvines. In June 1914 it was decided to build a national monument on the battlefield, which should contain a monumental equestrian statue of King Philip II. The aim was to emulate the Germans who erected the Monument to the Battle of the Nations the previous year . The project finally failed a few weeks later after the outbreak of the First World War . After the Second World War , Bouvines lost its meaning as a symbol of nationalist thought in the face of the emerging European movement and reconciliation with Germany . It disappeared completely in French school books, the battle was only briefly mentioned in the school textbooks.

literature

- Dominique Barthélemy: La bataille de Bouvines. Histoire et legends. Perrin, Paris 2018, ISBN 978-2-262-06531-7 .

- Alexander Cartellieri : Philip II August, King of France. Volume 4, Part 2: Bouvines and the End of Government. (1207-1223). Dyk, Leipzig 1922, p. 448 ff.

- Georges Duby : Le Dimanche de Bouvines (= Trente journées qui ont fait la France. Vol. 5). Gallimard, Paris 1973 (German: Der Sonntag von Bouvines. (The day on which France came into being). Wagenbach, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-8031-3608-3 ).

- Pierre Monnet , Claudia Zey : (Ed.) Bouvines 1214-2014. Histoire et mémoire d'une bataille - A battle between history and memory. Winkler, Bochum 2016, ISBN 3-89911-253-9 .

Web links

- Report by Wilhelm Brito from the Gesta Philippi Augusti (English)

- The chants X. to XII. from the Philippide of Wilhelm Brito (English)

- Report by Roger of Wendover from the Flores Historiarum (English)

- Report by Anonymus von Béthune from the Chronique des rois (English)

Remarks

- ↑ The alliance agreement is dated June 29, 1198. See Léopold Delisle (Ed.): Catalog des actes de Philippe Auguste. Durand, Paris 1856, p. 127, no.535 .

- ↑ The Treaty of Vaucouleurs is dated November 19, 1212. See Léopold Delisle (ed.): Catalog des actes de Philippe Auguste. Durand, Paris 1856, p. 320, no.1408 .

- ↑ For the numbers of troop strengths see Jan F. Verbruggen: De Krijgskunst in West-Europa in de Middeleeuwen. (IXe tot begin XIVe eeuw) (= Negotiating van de Koninklijke Academie voor Wetenschappen, Letteren en Schone Kunsten van Belgie. Class of letters. No. 20, ISSN 0770-1047 ). Paleis der Academiën, Brussels 1954.

- ^ Karl Schnith : Bouvines, battle of (1214) . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 2, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1983, ISBN 3-7608-8902-6 , Sp. 522 f.

- ^ Wilhelm Brito: De Gestis Philippi Augusti. In: Recueil des Historiens des Gaules et de la France (RHGF). Volume 17: Michel-Jean-Joseph Brial: Monumens des règnes de Philippe-Auguste et de Louis VIII, depuis l'an MCLXXX jusqu'en MCCXXVI. Livraison 1. Nouvelle édition, publiée sous la direction de Léopold Delisle. Palmé, Paris 1878, pp. 95-101 .

- ↑ Georg Waitz (ed.): De Pugna Bovinis. In: Georg Waitz (Ed.): Ex rerum Francogallicarum scriptoribus. Ex historiis auctorum Flandrensium Francogallica lingua scriptis (= Monumenta Germaniae Historica. 1: Scriptores. 5: Scriptores (in Folio). Vol. 26, ISSN 0343-2157 ). Hahn, Hannover 1882, pp. 390–393 .

- ^ Extrait d'une chronique française des rois de France par un Anonyme de Béthune. In: Recueil des historiens des Gaules et de la France (RHGF). Volume 24: Léopold Delisle: Les enquêtes administratives du règne de Saint Louis et la chronique de l'anonyme de Béthune. Part 2. Imprimerie Nationale, Paris 1904, pp. 767-770.

- ^ Roger of Wendover's Flowers of History. Comprising the History of England from the Descent of the Saxons to 1235. Formerly ascribed to Matthew Paris. Translated from the Latin by John A. Giles. Volume 2. Henry G. Bohn, London 1849, pp. 298-302 .

- ↑ Georg Waitz (Ed.): Richeri Gesta Senoniensis ecclesiae Liber III. In: Georg Waitz (Ed.): Gesta saec. XIII (= Monumenta Germaniae Historica. 1: Scriptores. 5: Scriptores (in Folio). Vol. 25). Hahn, Hanover 1880, Cap. 14-16, pp. 293-296 ; Richer was wrong here, since Galon de Montigny actually carried the royal lily banner.

- ↑ Both transcriptions were reissued by Victor Le Clerc in 1856 and can be read today in the Histoire littéraire de la France (vol. XXIII, pp. 433–436).

- ^ François-Eude de Mézeray: Histoire de France depuis Faramond jusqu'à maintenat (3 volumes, 1643); Guillaume Marcel: Histoire des origines et des progrès de la monarchie française suivant l'ordre des temps (4 volumes, Paris, 1686)

- ^ François Guizot: Cours d'histoire moderne (1840)

- ^ François Guizot: L'Histoire de la France (1883)

- ^ Augustin Thierry: Lettres sur l'histoire de France (1827)

- ↑ D. Blanchet, J. Périard: Cours d'histoire à l'usage de l'enseignement primaire (1903) ; C. Calvet: Cours (1903)

Coordinates: 50 ° 35 ′ 0 ″ N , 3 ° 13 ′ 30 ″ E