autism

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| F84.0 | Early childhood autism |

| F84.1 | Atypical autism |

| F84.5 | Asperger syndrome |

| F84.9 | Unspecified profound developmental disorder |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

Autism (from ancient Greek autós "self") is a pervasive developmental disorder that is diagnosed as an autism spectrum disorder . This usually occurs before the age of three and can show up in one or more of three areas:

- Problems with mutual social interaction and exchange (such as understanding and building relationships)

- Abnormalities in linguistic and non-verbal communication ( e.g. eye contact and body language )

- limited interests with repetitive, stereotypical behavior

Because of their limitations, many autistic people need help and support, sometimes for life. Autism is independent of the development of intelligence , but intellectual disability is one of the frequent additional restrictions. Despite extensive research, there is currently no generally accepted explanation of the causes of autistic disorders.

In the current ICD-10 classification system , a distinction is made between different forms of autism ( e.g. early childhood , atypical autism and Asperger's syndrome ). The DSM-5 and the ICD-11 (valid from 2022), on the other hand, no longer contain any subtypes and only speak of a general autism spectrum disorder (ASS; English autism spectrum disorder , ASD for short ). The reason for this change was the increasing knowledge in science that a clear delimitation of subtypes is not (yet) possible - and instead one should assume a smooth transition between mild and stronger forms of autism.

Main symptoms

The ICD-10 defines the following:

“This group of disorders is characterized by qualitative deviations in mutual social interactions and communication patterns and by a restricted, stereotypical, repetitive repertoire of interests and activities. These qualitative abnormalities are a fundamental functional characteristic of the affected child in all situations. "

history

To the subject

The Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler coined the term autism around 1911 as part of his research on schizophrenia . Initially, he only referred to this disease and wanted to describe one of its basic symptoms - the withdrawal into an inner world of thought. Bleuler understood autism to be "the detachment from reality together with the relative or absolute predominance of inner life." (Original quote)

Sigmund Freud took over the terms “autism” and “autistic” from Bleuler and roughly equated them with “ narcissism ” or “narcissistic” - as opposed to “social”. The meaning of the term changed over time from “living in one's own world of thoughts and ideas” to “self-centeredness” in a general sense.

Diagnosis emergence

Hans Asperger and Leo Kanner then took up the term autism (see historical literature ), possibly independently of one another. However, they no longer saw it as just a single symptom (like Bleuler), but tried to grasp an entire disorder of its own. They differentiated people with schizophrenia, who actively withdraw into their inner being, from those who live in a state of inner seclusion from birth . The latter now defined the term “autism”.

Kanner defined the term “autism” narrowly, which essentially corresponded to what is now known as early childhood autism (hence: Kanner syndrome ). His point of view achieved international recognition and became the basis for further autism research. Asperger's publications, on the other hand, described “autism” somewhat differently and were initially barely noticed internationally. This was partly due to the overlap with the Second World War and partly to the fact that Asperger published in German and his texts were not translated into English for decades. Hans Asperger himself called the syndrome he described "autistic psychopathy". The English psychiatrist Lorna Wing (see historical literature ) continued his work in the 1980s and first used the term Asperger's Syndrome . Asperger's research did not gain international fame in specialist circles until 1990.

Old subtypes

In the German-speaking countries, three types of diagnosis of autism are common:

- The early childhood autism (including autistic disorder called). The most noticeable features besides the behavioral deviations are: due to the early occurrence, severely restricted language development; motor impairments only with further disabilities; often mentally handicapped.

- Depending on the mental capabilities, early childhood autism is further divided into Low, Intermediate and High Functioning Autism (LFA, IFA and HFA). In the English-speaking world, LFA refers to the early childhood autism associated with intellectual disabilities, and HFA refers to those with a normal or above-average level of intelligence. The distinction between HFA and the Asperger's syndrome listed below has not yet been clarified, which is why the terms are sometimes used synonymously .

- The atypical autism not met all the diagnostic criteria of childhood autism, or only becomes apparent after the age of three. As a sub-form of early childhood autism, it is differentiated diagnostically from Asperger's syndrome.

- The Asperger's syndrome - also outdated autistic psychopathy or schizoid psychopathy in childhood (1926) - differs from other subtypes especially by the time her age-appropriate language development and correct from a formal point of language. In the ICD-10 and DSM-IV , age-appropriate language development is a diagnostic criterion - whereas according to Gillberg & Gillberg, delayed language development is a possible diagnostic criterion. People with Asperger's Syndrome often have poor motor skills .

In DSM-5 (2013) and ICD-11 (2018), all individual categories were grouped under autism spectrum disorders (ASD) . The reason for this was that the researchers today assumed that it was less a question of qualitatively different diseases than a continuum of very mild to severe forms of a developmental disorder that began in early childhood. In terms of symptoms, a distinction is made between deficits in two categories: First, social interaction and communication are disrupted (for example, eye contact, the ability to communicate or build relationships are weak). Second, repetitive behaviors and fixed interests and behaviors are hallmarks of autistic disorders.

| early childhood autism (LFA and HFA) | Asperger's Syndrome (AS) | |

| first abnormalities | from 10th to 12th Month of life | from 4 years of age |

| Eye contact | seldom, fleeting | seldom, fleeting |

| language | in half of the cases the lack of language development; Otherwise delayed language development, often echolalia in the beginning , exchange of pronouns | early development of a grammatically and stylistically superior language, often a pedantic style of speech, problems understanding metaphors and irony |

| intelligence | mainly categorized as intellectual disability (LFA), partly normal to high intelligence (HFA -> AS) | normal to high intelligence, partly gifted |

| Motor skills | No abnormalities that can be traced back to autism. | often motor disorders, clumsiness, coordination disorders |

Early childhood autism

The three most important areas affected in early childhood autism are:

Social interaction

A qualitative impairment of social interaction is sometimes already evident in the first months of life due to a lack of contact with parents, especially with the mother. Many children with early childhood autism do not reach out to their mother to be lifted. They do not smile back when smiled at and do not make proper eye contact with their parents.

Recent research suggests that both cognitive and emotional empathy are impaired in people with autism. Children with early childhood autism also show a strong object-relatedness, which is often limited to a certain type of object. Your attention is focused on a few things, such as faucets, door handles, joints between stone slabs or checkered paper, which attract you very strongly, so that everything else becomes secondary and is ignored or hardly noticed. Often they find a normally unusual systematics in objects (for example sorting the individual parts of a toy train according to size and color) or application (for example, their only interest in a toy car is to keep turning the wheels).

communication

About every second child with early childhood autism does not develop spoken language. In the others, language development is delayed. The development of spoken language often takes place over a long phase of echolalia , some of the affected people do not get beyond this phase. In childhood, the pronouns are often exchanged (pronominal inversion). They speak of others as "I" and of themselves as "you" or in the third person. This quirk usually improves with development. In addition, there are often problems with yes / no answers, what is said is instead confirmed by repetition. There are also problems with semantics: word creations ( neologisms ) occur frequently. Some people with early childhood autism also cling to certain formulations ( perseveration ). The impairment of pragmatics is most pronounced : When communicating with other people, autistic people have difficulty understanding what is said beyond the precise meaning of the word, and reading between the lines. Her voice often sounds monotonous (lack of prosody ).

The problems in communication manifest themselves in difficult contact with the outside world and with other people. Some autistic people hardly seem to notice the outside world and communicate with their environment in their own very individual way. This is why autistic children used to be called shell children or hedgehog children . The visual and auditory perceptions are often unusually intense. Therefore, there is sometimes the assumption that shutdown functions in the brain as self-protection would reduce possible overstimulation . Autistic people have a different need for body contact. On the one hand, some people make direct and sometimes socially inappropriate contact with strangers, on the other hand, every touch can be unpleasant for them due to the over-sensitivity of their sense of touch .

With this in mind, understanding communication with an autistic person is difficult. Emotions are often misinterpreted or not understood at all. These possible problems must be taken into account when making contact and require great empathy and imagination.

Repetitive and stereotypical behavior patterns

Changes in their environment (such as moving furniture or another way to school) worry and unsettle some autistic people. Sometimes those affected panic when objects are no longer in their usual place or in a certain arrangement, or they are completely upset by an unannounced visit or a spontaneous change of location. Actions are usually ritualized, and deviations from these rituals lead to chaos in the head, because autistic people usually have no alternative strategies in the event of unexpected changes in situations or processes.

The following repetitive (repetitive) stereotypes - so-called stimming - can occur in severely autistic people :

- Jaktationen (swings with the head or upper body),

- walking around in circles or twisting fingers,

- Touch surfaces

- Occasionally also self-injurious behavior, such as gnawing fingers bloody, biting nails beyond the nail bed, banging the head, hitting the head with the hand, scratching oneself, biting or other things. This self-injurious behavior leaves more or less visible traces such as bite marks, scars and scabbed wounds on the skin.

- Such self-harming behaviors are not to be confused with consciously self-harming behavior , which is typically used to reduce tension (e.g. through burns or scratches on the forearm) or - less often - emerges from suicidal tendencies and then shows a different (suicidal) injury pattern.

Repetitive behaviors are calming for all people (like dolls or teddy bears in small children that are taken everywhere) and may be more indicative of severe stress than autism itself, which begs the question of why autistic people tend to experience too much stress. Positive effects of repetitive behavior are used, for example, in yoga , and there are also adapted yoga classes that take autistic characteristics into account.

Highly functional autism

If all symptoms of early childhood autism appear together with normal intelligence (an IQ of more than 70), one speaks of high-functioning autism (HFA). The delayed speech development is particularly important diagnostically here. Compared to Asperger's syndrome, the motor skills are usually significantly better.

Often, due to the delay in language development, low-functional early childhood autism (LFA) is diagnosed first. However, normal language development can then take place later, at which a functional level comparable to Asperger's syndrome is achieved. As adults, many autistic HFAs cannot be distinguished from autistic Asperger's, but mostly the autistic symptoms remain much more pronounced than in Asperger's syndrome. The language does not necessarily have to develop, many non-speaking HFA autistic people can still live independently and learn to express themselves in writing. Internet-based forms of communication help these people in particular to significantly improve their quality of life.

Atypical autism

Atypical autism differs from early childhood autism in that children after the age of three show autistic behavior (atypical age of onset) or do not show all symptoms (atypical symptoms).

Autistic children with an atypical age of onset show the symptoms of early childhood autism, which does not manifest itself in them until they are three years old.

Autistic children with atypical symptoms display abnormalities that are typical of early childhood autism, but do not fully meet the diagnostic criteria for early childhood autism. The symptoms can manifest themselves both before and after the age of three.

In the psychiatric diagnostic manual ( DSM-IV ), which is used especially in the USA, there is no diagnosis of “atypical autism”; instead, “profound developmental disorder - no other description” (PDD-NOS) is used as the diagnosis. Colloquially, PDD-NOS is often incorrectly referred to as “profound developmental disorder (PDD)”, which only describes the diagnostic category but is not itself a diagnosis.

When atypical autism occurs together with significant intellectual retardation, it is sometimes referred to as "intellectual retardation with autistic features". However, recent research suggests that the assumption of intellectual disability in autistic people is falsified with the Wechsler IQ test , and that autistic people do up to 30 points better on the Ravens matrix test, which indicates not less but different intelligence.

Asperger syndrome

Asperger's syndrome (AS), named after the Austrian physician Hans Asperger, is considered a mild form of autism and manifests itself around the age of four. Although many behaviors make heavy demands on the social network of those affected, especially that of close friends and family , there are not only negative aspects of Asperger's Syndrome. There are numerous reports of the simultaneous occurrence of above-average intelligence or island talents . Lighter cases of Asperger's syndrome in English colloquially "Little Professor Syndrome", " Geek Syndrome" or " Nerd called Syndrome".

Social interaction

One of the most serious problems for people with Asperger's Syndrome is the impairment of social interaction behavior, especially in two areas: on the one hand, in a restricted ability to establish informal relationships with other people, and on the other hand, restrictions on non-verbal communication .

Children and adolescents with Asperger's Syndrome often lack the desire to establish relationships with their peers. This desire usually only arises in their adolescence , but then they usually lack the ability to do so.

The impairments in the area of non-verbal communication concern both the understanding of other people's non-verbal messages and the sending of one's own non-verbal signals. In some cases, this also includes adjusting the pitch and volume of your own language.

Social interaction proves to be particularly problematic, as people with Asperger's Syndrome have no obvious external signs of disability. It can happen that the difficulties of people with Asperger's Syndrome are perceived as a deliberate provocation, when this is not the case. If, for example, a person only responds to a question put to them in silence, this is often interpreted as stubbornness and rudeness.

In everyday life, the difficult social interaction makes itself felt in many ways. People with Asperger's Syndrome have difficulty making or maintaining eye contact with other people. You avoid body contact such as shaking hands. You are insecure when it comes to having conversations with others, especially when it comes to rather trivial small talk . People with Asperger's Syndrome do not intuitively understand social rules that others intuitively master, but have to learn them first. As a result, people with Asperger's Syndrome often have no friends or fewer friends. At school, for example, they prefer to be on their own during breaks because they have little knowledge of how other students interact with each other. In class, they are usually much better in the written than the oral area. In their training and at work, the technical area usually does not cause them any difficulties, only small talk with colleagues or contact with customers. Telephoning can also cause problems. Oral exams or lectures can be major hurdles in teaching and studying. Since contact and teamwork are just as important as professional aptitude in all areas of the job market, people with Asperger's Syndrome have problems finding a suitable job at all. Many are self-employed, but they can hardly assert themselves in the event of problems with customers. In a workshop for disabled people , however, they would be completely under-challenged.

Most people with Asperger's Syndrome are able to maintain a facade through their high acting skills, so that their problems are not immediately visible at first glance, but show through in personal contact, for example in an interview . Outwardly, people with Asperger's Syndrome are considered extremely shy, but that's not the real problem. Shy people understand the social rules but do not dare to apply them. People with Asperger's Syndrome would dare to use it, but do not understand it and therefore have problems dealing with it. The ability for cognitive empathy (empathy) is not at all or only weakly developed. With regard to affective empathy (compassion) towards others, a review article from 2013 showed inconsistent results: less than 50% of the studies showed a reduction in emotional perception.

People with Asperger's Syndrome can hardly put themselves in other people's shoes and read their moods or feelings from external signs. In general, they find it difficult to read between the lines and understand non-literal meanings of expressions or phrases. They are offensive because they do not understand the non-verbal signals that are obvious to other people. Since it is usually difficult for them to name and express feelings, it often happens that others misinterpret this as a lack of personal interest. They can also get into dangerous situations, as they are often unable to correctly interpret external signs that indicate an impending danger - for example from fraudsters or violent criminals.

Stereotypical patterns of behavior and special interests

People with Asperger's Syndrome show repetitive and stereotypical behavior patterns in their way of life and in their interests. The life of people with Asperger's Syndrome is determined by well-developed routines. If they are disturbed in these, they can be significantly impaired. In their interests, people with Asperger's Syndrome are sometimes limited to one area in which they usually have enormous specialist knowledge. What is unusual is the extent to which they devote themselves to their area of interest; They are usually difficult to inspire for areas other than their own. Since people with Asperger's Syndrome can usually think logically, their areas of interest are often in the mathematical and scientific field; the entire humanities palette, but also other areas are possible.

Ritualized and stereotypical thinking and perception

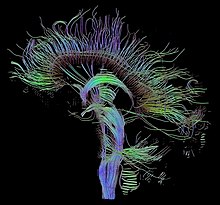

In addition to motor schemes, stereotypes and repetitive speech acts, ritualized actions can also include repetitive and stereotypical forms of thinking and perception. These consist in the concentration on a few special interests, which are pursued with great intensity. The intensive development of such special interests can lead to the development of special skills, which may be more or less pronounced (to be distinguished from island talents ). This is where neural fields and networks of high local connectivity emerge, which, however, are only weakly connected to other areas through global connectivity in the brain.

Island talent

The interests of autistic people are often focused on specific areas. However, some have exceptional skills in such a field, for example in mental arithmetic, drawing, music or memory. One then speaks of an " island talent ". Those who have them are also called savants . About 50 percent of the islanders are autistic. Conversely, only a small proportion of autistic people are gifted on islands.

Diagnosis and classification

According to the data of 178 patients diagnosed only in adulthood (period 2005–2009) at the Cologne special clinic specializing in autism, the first diagnosis was made at an average age of 34 years.

When diagnosing it, it is important to note that the individual symptoms are not autism-specific, as similar characteristics also occur in other disorders. Rather, it is only the combination of several of these symptoms that is specific to autism. H. the constellation of symptoms.

According to ICD-10

Autism is listed in the fifth chapter of the ICD-10 as a pervasive developmental disorder . It is subdivided under the key F84 as follows:

- F84.0: autism; also referred to as: early childhood autism, infantile psychosis, infantile autism, Kanner syndrome, childhood psychosis

- F84.1: atypical autism; also known as: Atypical psychosis in childhood

- F84.10: autism with atypical age of onset

- F84.11: Autism with atypical symptoms

- F84.12: Autism with atypical age of onset and atypical symptoms

- F84.5: Asperger's Syndrome; Also referred to as: Autistic Psychopathy, Childhood Schizoid Disorder

The alternative names mentioned above are out of date, but can still be found in the ICD-10 today. The revised version of the ICD-11 is expected in 2018.

According to DSM-5

The DSM-5 (the American classification of mental disorders ) summarizes all forms of autism in the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) . The diagnostic criteria of ASA are divided into five areas (A – E):

- A) Persistent deficits in social communication and interaction across different contexts. These manifest themselves in the following current or past fulfilled characteristics:

- Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity (e.g. unusual social rapprochement; lack of normal mutual conversation, reduced exchange of interests, feelings and affects )

- Deficits in non-verbal communication behavior used in social interactions (e.g. less or no eye contact or body language; deficits in the understanding and use of gestures up to a complete lack of facial expressions and non-verbal communication)

- Deficits in establishing, maintaining and understanding relationships (e.g. difficulties in adapting one's own behavior to different social contexts, in exchanging ideas in role-playing games or making friends)

- B) Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities that manifest themselves in at least two of the following currently or past fulfilled characteristics:

- Stereotypical or repetitive motor movements; stereotypical or repetitive use of objects or language (e.g. echolalia , lining up toys, moving objects back and forth, idiosyncratic language use)

- Clinging to the same, inflexible clinging to routines or ritualized patterns (e.g. extreme discomfort with small changes, difficulties with transitions, rigid thought patterns or greeting rituals, need to walk the same path every day)

- Highly limited, fixed interests that are abnormal in their intensity or content (e.g. strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects, extremely circumscribed or persevering interests)

- Hyper or hyporeactivity to sensory stimuli or unusual interest in environmental stimuli (e.g., apparent indifference to pain or temperature, negative reaction to specific sounds or surfaces, excessive smelling or touching objects)

- C) Symptoms must be present in early childhood, but can only fully manifest when social demands exceed limited possibilities. (In later phases of life, they can also be masked by learned strategies.)

- D) Symptoms must cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, professional, or other important functional areas.

- E) Symptoms cannot be better explained by Intellectual Impairment or General Developmental Delay. Intellectual impairment and autism spectrum disorder often coexist. In order to be able to make the diagnoses of Autism Spectrum Disorder and Intellectual Impairment together, social communication skills should be below the level expected based on general development.

Based on the impairments in social communication and restricted, repetitive behavioral patterns, the current severity is determined:

- Severity 3: "very extensive support required"

- Severity 2: "extensive support required"

- Severity 1: "Assistance Required"

DSM 5 expressly points out that people with a confirmed DSM-IV diagnosis of an autistic disorder, Asperger's syndrome or unspecified profound developmental disorder should be diagnosed with ASD. In the case of clear social communication deficits, which otherwise do not meet the criteria of the autism spectrum disorder, the diagnosis of social communication disorder should be considered.

Differential diagnosis

Autistic behaviors can also occur with other syndromes and mental illnesses. Autism must therefore be distinguished from these:

- ADHD

- The attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder is from Asperger's syndrome is difficult to distinguish if the attention deficit disorder with no accompanying impulsivity and hyperactivity occurs and there are additional current through them social deficits. In Asperger's Syndrome, however, the impairments in social and emotional exchange, the special interests and the detail-oriented style of perception are more pronounced. Conversely, severe disorganization with erratic thinking and action can often be observed in ADHD, which is not typical for autism.

- Angelman Syndrome

- The Angelman Syndrome is superficially very similar to the early childhood autism. However, it represents a change on the 15th chromosome and can be proven genetically .

- Attachment disorder

- When attachment disorder that is language skills - unlike the atypical and childhood autism - intact. A differentiation from highly functional autism and Asperger's Syndrome can be difficult in individual cases. The anamnesis plays an important role here. Neuropsychological tests are another basis for clear differentiation. However, autism is not an attachment disorder, and autistic people are not disturbed in their emotional attachment, even if their relationships may be atypical.

- Borderline personality disorder

- Some authors see parallels to borderline personality disorder , especially in women , in which the ability to empathize is also impaired and non-verbal signals are more difficult to recognize. Unlike autistic patients, however, borderline patients rarely have special interests or show particularly rational thinking; Autistic people, on the other hand, do not suffer from the pronounced mood swings that are usually found in borderliners.

- Fragile X Syndrome

- The fragile X syndrome is triggered by a genetic defect that can be clearly detected with appropriate analysis methods and differentiated from autism.

- Heller syndrome

- The Heller's syndrome is one such ASS to the pervasive developmental disorders according to ICD-10. It causes a general loss of interest in the environment, stereotypes and motor mannerisms. The social behavior is similar to that of an autistic person.

- Hearing impairment

- A hearing impairment may at first glance also ( hearing loss or deafness are confused in children with autism) because the child does not respond to loud noises or speech and because the language development delays . A hearing test or hearing screening (regularly carried out in children before starting school ) provides clarity.

- Autism-like behavior

- Autistic behavior in the case of psychological hospitalism , child abuse and neglect differs from autism in that it occurs primarily from birth. Typical behaviors in autistic people are not triggered by improper parenting, lack of love, abuse, or neglect. In those cases, the autistic behavior disappears again when the external circumstances improve, whereas autism is incurable.

- anorexia

- In anorexia (anorexia nervosa) rigid eating habits and can social isolation occur occasionally reminiscent of high-functioning autism or Asperger syndrome. The main differentiator to autism is that in anorexia, both symptoms appear only for a limited time and disappear again after the cause has been rectified. However, as early as 1994, Gillberg found in an epidemiological study that 6 out of 51 cases of anorexia nervosa in early adulthood had Asperger's syndrome.

- Mutism

- In contrast to autism, mutism is more related to social anxiety and manifests itself exclusively as a communication disorder , not as a developmental disorder (as is the case with autism). A distinction is made between total mutism (the patient does not speak at all despite the functional ability to speak ) and selective or elective mutism (use of language depends on people and situations).

- Rett Syndrome

- The Rett Syndrome is one such ASS to the pervasive developmental disorders according to ICD-10. It occurs almost exclusively in women; typical symptoms are autistic behavior and disorders of the coordination of movements ( ataxia ).

- Schizoid Personality Disorder (SPS)

- Differentiating between highly functional autism and Asperger's syndrome and schizoid personality disorder can be difficult in individual cases. Because some people with Asperger's Syndrome (up to 26%) also meet the criteria for schizoid PS. Social communication (facial expressions, gestures, eye contact, etc.) can be conspicuous with both diagnoses. In contrast to atypical and early childhood autism, however, there is no intellectual disorder in schizoid personality disorder. That is why the anamnesis is important, because autism has always existed since childhood. Another distinguishing feature is the pronounced flattening of affect in schizoid people. They also (in contrast to autism) usually show normal emotionality and inconspicuous social behavior up to puberty. It is also different that schizoid people often appear reserved, withdrawn and closed (or even “secretive”) and tend to be reluctant to talk about themselves. So you try to avoid self-disclosure .

- In contrast, many people with mild autism are often very open-hearted, honest, direct, and occasionally unintentionally intrusive. Those affected are often only slightly afraid of giving others an insight into their inner workings. This can be seen in the very open and (sometimes naive) personal portrayal in the many autobiographies of autistic people and in public interviews. As an adult, you often want friends and acquaintances. However, because of their difficulty in perceiving complex feelings in the other person or in reacting to them appropriately, they are often only able to form friendships to a limited extent.

- schizophrenia

- Schizophrenia differs mainly in the occurrence of hallucinations, delusions and ego disorders that do not occur in autism. In contrast to schizophrenia simplex , autism or Asperger's syndrome has existed since childhood.

- Dumbness, aphasia

- Dumbness , aphasia or some other form of speech development delay can at first glance simulate autistic behavior in children because the linguistic utterances are missing. However, normal social behavior distinguishes mute from autism or Asperger's syndrome.

- Urbach-Wiethe syndrome

- The Urbach-Wiethe syndrome is a very rare neurological disorder that leads to skin changes, changes in the mucous membrane ( hoarseness ) and difficulties in communication and social behavior . Sufferers have trouble interpreting other people's expressions and following conversations . The skin and mucous membrane changes that occur at the same time enable a differentiation from autism. A genetic test can provide clarity.

- Obsessive-compulsive illness

- People who suffer from compulsive acts are generally not affected by social and communication skills. In contrast to people with obsessive-compulsive disorder, autistic people do not experience their routines as being imposed against their will, but create security for them and they feel comfortable with them ( ego synton ). However, some people with Asperger's Syndrome also meet the criteria for compulsive personality disorder ; a differential diagnosis is normally also possible here.

Accompanying disturbances

Various accompanying ( comorbid ) physical and mental illnesses can occur together with autism :

- The attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) must not only be distinguished from autism, but can also occur in addition to autism.

- Depression , psychoses , phobias , post-traumatic stress disorder , obsessive-compulsive disorder , eating disorders , sleep disorders : if the autistic disorder remains undetected and untreated for a long time, various additional disorders can spread like a fan. This is why early diagnosis is so important.

- Epilepsy describes a clinical picture with at least two recurring spontaneous seizures that were not caused by a previous recognizable cause.

- Prosopagnosia (facial blindness): Difficulty recognizing faces. Some people with autism perceive people and faces as objects. Recent research has found that some people with autism process the visual information when looking at people and faces in a part of the brain that is actually responsible for perceiving objects. They then lack the intuitive ability to recognize faces in a fraction of a second and to assign them to events.

- The Tourette's syndrome is a mental disorder characterized by the occurrence of tics is characterized.

- Tuberous sclerosis is a genetic disease that is associated with malformations and tumors of the brain, skin changes and mostly benign tumors in other organ systems. Clinically, it is often characterized by epileptic seizures and cognitive disabilities.

frequency

An analysis of 11,091 interviews from 2014 by the National Center for Health Statistics of the USA found a frequency ( lifetime prevalence ) of ASD of 2.24% in the age group 3–17 years, 3.29% in boys and 1.15% in girls .

A 2015 overview showed that the numbers on the gender distribution varied greatly due to methodological difficulties. The male-female ratio is at least 2: 1 to 3: 1, which indicates a biological factor in this question.

The number of autism cases seems to have risen sharply in the past few decades. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in the United States reported a 57% increase in autism cases (between 2002 and 2006). In 2006, 1 in 110 children aged 8 years had autism. Although better and earlier diagnostics play a role, according to the CDC it cannot be ruled out that part of the increase is due to an actual increase in cases.

However, autism is not only present as a disease in the population, but also as a personality trait lying on a continuum . Various characteristics are associated with this personality trait, for example poorer social skills and increased attention to detail.

There used to be a suspicion that environmental toxins or vaccine additives could promote the development of autism. As of 2017, the latter is considered refuted and the former as insufficiently researched.

The following factors have played a role in the recent increase in the number of cases:

- Attending kindergartens more often and getting children to start school earlier increases the chance that autism will be discovered.

- Today, parents pay more attention to whether their children are developing “normally”. In the past, a child was often only brought to the doctor when it was noticeably late in learning to speak.

- The definition of autism has been broadened so that more children are diagnosed as autistic.

- In the past, autism was often classified under childhood schizophrenia or attention deficit / hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Consequences and prognosis

Autism can significantly impair personality development , job opportunities and social contacts. The long-term course of a disorder from the autism spectrum depends on the individual characteristics of the individual patient. The cause of autism cannot be treated because it is not known. Only supportive treatment is possible in individual symptom areas .

On the other hand, many of the difficulties that autistic people report can be avoided or reduced by adapting their environment. For example, some report a pain sensation for certain sound frequencies . Such people are much better off in a low-stimulus environment. Finding or creating an autism-friendly environment is therefore an essential goal.

Communication training for autistic people as well as their friends and relatives can be helpful for everyone involved and is offered and scientifically developed by the National Autistic Society in Great Britain , for example . An increasing number of schools, colleges and employers especially for autistic people demonstrate the success of allowing autistic people to live in an autism-friendly environment.

According to the (German) law for severely disabled people, the autistic syndromes belong to the group of mental disabilities . According to the principles of the Health Care Ordinance , the degree of disability is 10 to 100, depending on the extent of the social adjustment difficulties.

In early childhood and atypical autism, an improvement in the symptom picture usually remains within narrow limits. About 10–15% of people with early childhood autism achieve an independent lifestyle in adulthood . The rest usually require intensive, lifelong care and sheltered accommodation .

There are still no studies on the long-term course of Asperger's syndrome. Hans Asperger himself assumed a positive long-term course. As a rule, people with Asperger's Syndrome learn in the course of their development to compensate for their problems to a greater or lesser extent, depending on their level of intellectual ability. British autism expert Tony Attwood compares the development process of people with Asperger's Syndrome to creating a puzzle: over time, they get the pieces of the puzzle together and see the whole picture. This is how they can solve the puzzle (or riddle) of social behavior. After all, people with Asperger's Syndrome can reach a status in which their disorder is no longer noticeable in everyday life.

There are a number of books on autistic people. The neurologist Oliver Sacks and psychologist Torey Hayden have published books about their patients with autism and their ways of life. Among the books written by autistic people, the works of the American animal scientist Temple Grandin , the Australian writer and artist Donna Williams , the American educationalist Liane Holliday Willey and the German writer and filmmaker Axel Brauns are particularly well-known.

School, training, job

Which school is suitable for people with autism depends on the intelligence , language development and degree of autism in the individual. If intelligence and language development are normal, children with autism can attend regular school. Otherwise, attending a special school can be considered. However, many people with autism are only diagnosed after leaving school.

With regard to training and occupation, the individual's level of development must also be taken into account. If intelligence and language development are normal, regular studies or regular vocational training can be completed. Otherwise, a job in a workshop for disabled people may be an option. In any case, it is important for the integration and self-esteem of autistic people to be able to pursue an activity that corresponds to their individual skills and interests .

On the one hand, entering into regular working life can be problematic, as many autistic people cannot meet the high social demands of today's working world . According to a study published by Rehadat in 2004, only about ten percent of autistic young people are able to meet the requirements of vocational training, since “in addition to the achieved cognitive performance level, the psychopathological abnormalities are decisive for the ability to train”, which means patience and possibly a longer phase of professional preparation required so that a rejection of young people who are in principle capable of training is avoided. Understanding supervisors and colleagues are essential for people with autism. Regulated work processes, clear tasks, manageable social contacts , clear communication and the avoidance of polite phrases, which can lead to misunderstandings, are also important.

On the other hand, people with autism syndrome and the partial performance levels associated with it (" island talent ") are in some cases particularly well suited for certain professions or activities, e.g. B. in computer science , etc. Many autistic people also meet the requirements for a course of study due to their cognitive performance, which can, however, be protracted due to the non-fixed structure. Sometimes there are special mediation agencies: In an ecological worldview it is important that very different people who live together in an " ecosystem " (in the case of humans, a socio-economic ecosystem) find suitable niches in which they can get along well. Finding or creating an environment suitable for autism, for example specialized schools, is therefore an essential goal. There are centers in the USA that provide adult autistic jobs, possibly in combination with assisted living. The Danish temporary employment agency Specialisterne demonstrates the success of placing autistic people in an autism-friendly environment. The right job for autistic people that takes into account the specific characteristics of the autistic person can be more difficult to find, but it can also be very fulfilling. There are hardly any specialized career counseling for the autism spectrum, since the integration offices are responsible for autistic people in Germany. The Danish company plans to mediate in database management or programming in other countries as well . a. in which often specially gifted people with autism can even be better than others. In this way, a phenomenal number memory can be used - always without a noisy open-plan office and with moderate working hours, etc. At the end of 2011, the Auticon company was founded in Berlin . She has specialized in using the often enormous talents of people with Asperger's autism, for example in the quality control of software. The Israeli armed forces prefer to use autistic people when evaluating aerial photos.

The British psychologist Attwood writes about the diagnosis of slightly autistic adults that they sometimes get along well if they have found a suitable job, but in the case of crises - for example through unemployment - from their knowledge of Asperger's Syndrome to cope with crises can benefit.

treatment

Based on the individual development, a plan is drawn up in which the type of treatment for individual symptoms is determined and coordinated with one another. In accordance with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities ), a suitable environment should be created in which all parties involved learn how to best take into account the characteristics of the child. In the case of children, the entire environment (parents, families, kindergarten, school) is included in the treatment plan. In many places, offers for adults are only just being established.

The UK's National Autistic Society has published an overview of applications, therapies and interventions . A selection of treatment methods is briefly presented below.

A comprehensive overview from 2013 by the Freiburg Autism Study Group is available for treatment in adults. The systematic evaluation of treatment attempts in older adolescents and adults is (as of 2017) - in contrast to the situation with children - still unsatisfactory, which was attributed to the historically later attention when recording these age groups.

Behavior therapy

The behavioral therapy is in the autism therapy the most scientifically validated form of therapy. A comprehensive study from 2014 is available on the active factors of behavior therapy in autimus. The aim is, on the one hand, to break down disruptive and inappropriate behaviors such as excessive stereotypes or (auto) aggressive behavior and, on the other hand, to develop social and communicative skills. In principle, the procedure is such that desired behavior is consistently and recognizable rewarded ( positive reinforcement ). Behavioral therapies can either be holistic or target individual symptoms.

The Applied Behavior Analysis ( Applied Behavior Analysis , ABA) is a holistic therapy that has demonstrated in the 1960s by Ivar Lovaas was developed. This form of therapy is geared towards early intervention. First of all, a system is used to determine which skills and functions the child already has and which not. Based on this, special programs are created that are intended to enable the child to learn the missing functions. The parents are involved in the therapy. ABA's procedures are essentially based on operant conditioning methods . The main components are a reward for correct behavior and cancellation for incorrect behavior. Learning attempts and successes as well as desired behavior are reinforced as directly as possible, with primary (innate) reinforcers (such as food) and secondary (learned) reinforcers (such as toys) being used to reward desired behavior. In the 1980s, ABA was further developed by Jack Michael, Mark Sundberg and James Partington, by including the teaching of language skills. There are currently only two institutes in the Federal Republic of Germany that offer this therapy.

Another holistic educational support concept is TEACCH (Treatment and Education of Autistic and related Communication-handicapped Children), which is aimed at both children and adults with autism. TEACCH aims to improve the quality of life of people with autism and to guide them to find their way around in everyday life. Central assumptions of the concept are that learning processes can be initiated through structuring and visualization in people with autistic characteristics.

Parent training

Parents of autistic children have been shown to experience significantly more stress than parents of children with other deviations or disabilities. Reducing the stress of the parents shows significant improvements in the behavior of their autistic children. There is strong evidence of a relationship between parents' stress levels and their children's behavioral problems, regardless of the severity of autism. The children's behavior problems do not show up, but also when the parents are under increased stress. The National Autistic Society developed the “NAS EarlyBird” program, a three-month training program for parents to prepare them effectively for the subject of autism.

Medication

The drug treatment of accompanying symptoms such as anxiety , depression , aggressiveness or compulsions with antidepressants (such as SSRIs ), atypical neuroleptics or benzodiazepines can be a component in the overall treatment plan . However, it requires special caution and careful observation, because it is not uncommon for them to aggravate the symptoms instead of alleviating them when used incorrectly.

Particular caution should be exercised when administering stimulants such as those prescribed for hyperactivity ( ADHD ), as they can intensify the latter even further in the presence of autism and the frequently occurring hypersensitivity to stimuli of the sensory organs. The effectiveness of methylphenidate is reduced in autistic people (approx. 50 instead of 75 percent of patients), undesirable side effects such as B. Irritability or difficulty sleeping. It should also be noted that over-stimulus sensitivity can occur independently of autism. A specific reference to autism is not mentioned in the package insert for individual stimulants.

Complementary measures

Possible supplementary methods include music , art and massage therapy, as well as riding and dolphin therapy or the use of therapy robots ( Keepon ) or echolocation sounds ( Dolphin Space ). You can increase the quality of life by having a positive effect on mood, balance and contact skills. In 2008, for example, a comprehensive science journalistic report about two autistic children of their own - with a dog.

Procedure without proof of effectiveness

Other known measures are restraint therapy , assisted communication and daily life therapy. These measures "are either extremely controversial and implausible in the context of the treatment of autism, or their assumptions and promises have been largely refuted by scientific research".

- The restraint therapy was developed in 1984 by the American child psychologist Martha Welch and distributed in the German-speaking area by Jirina Prekop . The starting point for this therapy is the assumption, which does not correspond to the current state of autism research, that autism is an emotional disorder that is caused by negative influences in early childhood. The affected child was unable to build up basic trust . In the very controversial restraint therapy, the resistance to closeness and body contact is broken by holding the child and thus the basic trust is subsequently developed. Concerning the restraint therapy “is not only the sometimes extremely dramatic and almost violent approach, but also the thesis on which the concept is more or less based that the child could not acquire the early basic trust. This is often interpreted by parents in terms of personal guilt for their autistic child ”.

- In the assisted communication method , the person with autism (assisted person) uses a communication aid (letter board, communication board, computer keyboard, etc. ) with physical assistance from an assisting person (supporter ). This joint operation creates a text, the authorship of which is attributed to the supported person. The supporters are introduced to supported communication in seminars. Criticism of the method can ignite. a. because it was possible to prove in blind tests that the supporter unconsciously and unintentionally influenced the writer, so that the supporter and not the supported person is the author of the text.

- The Daily Life Therapy was the first time in 1964 Japan applied. It is based on the basic hypothesis that a high level of anxiety in people with autism can be eliminated through physical exertion. Physical exertion leads to an increased release of endorphins , which have a pain-relieving or pain-suppressing ( analgesic ) effect.

Furthermore, there are various "biologically based" therapy methods - such as treatment with the intestinal hormone secretin - using high doses of vitamins and minerals or with special diets. Here, too, evidence of effectiveness is lacking, so that these measures are not recommended.

Suitable environment

Since the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities ) came into force , at least in Germany, an additional offer for children has been created to create a suitable environment so that disability is reduced by regulating the barriers. Developmental deficits can be partially compensated for if the children are treated well and in an environment that offers familiarity, tranquility, manageability and predictability. Whether additional medication should be prescribed here is discussed critically in the context of the debate about neurodiversity and handled differently.

Possible causes of autism

Possible causes or triggers of autism are now being researched in different areas of science. Today, however, the claims, still held up until the 1960s, that autism is caused by a cold mother (the so-called “ refrigerator mother ”), by loveless upbringing, lack of care or psychological trauma, are considered refuted .

Biological explanations

The biological causes of the entire spectrum of autism are developmental deviations in the development and growth of the brain. According to the current state of research, both anatomy and function, and in particular the formation of certain nerve connections ( connectome ), have changed. The subject of research is the possible causes of these deviations, which primarily - but not exclusively - affect embryonic development . In addition to special inherited genetic conditions, all factors that influence the work of the genes in critical time windows ( teratology ) come into question .

Genetic factors

The genetic causes of the full range of the autism spectrum have proven to be extremely diverse and highly complex. In an overview from 2011, 103 genes and 44 gene locations ( gene loci ) were already identified as candidates for participation, and it was assumed that the numbers would continue to rise sharply. It is generally assumed that the immense combination possibilities of many genetic deviations are the cause of the great diversity and breadth of the autism spectrum.

Since around 2010 it has become increasingly clear that, in addition to the hereditary changes that have been known for a long time, submicroscopic changes in chromosomes play a key role in autism , namely the copy number variations . First and foremost, it is a question of gene duplication or deletion . They arise during the formation of egg cells from the mother or from the father's sperm cells ( meiosis ). That is, they are created anew (de novo) . However, if a child receives such a deviation from a parent, it can pass it on, with a 50% chance. As a result, it is possible that a deviation that contributes to autism only occurs once in a child and is not inherited, or that it affects several family members in different generations. In the latter case, the impact ( penetrance and expressivity ) of such a genetic deviation can vary greatly from person to person (0–100%). Identical twins usually both have an autism spectrum disorder. Exceptions to this are attributed to environmental factors and epigenetic influences. Modern analysis methods ( DNA chip technology ) allow the determination of genetic deviations (analysis of the karyotype ) that lead to the manifestation of the spectrum disorder, whereby the involvement of family members is often helpful or even necessary. The results can then form the basis of genetic counseling .

Mirror neurons

Up until 2013, there was conflicting evidence to support the hypothesis that mirror neuron systems may not be adequately functional in people with autism. A meta-analysis from 2013 found that there was little to support the hypothesis and that the data was more compatible with the assumption that the descending (top-down) modulation of social responses is atypical in autism.

Deviations in the digestive tract

Although digestive disorders in connection with ASA have often been described, there are no reliable data to date (November 2015) on a possible correlation or even a possible causal relationship - neither in one direction nor in the other.

Masculinization of the brain

The theory that masculinization of the brain ( Extreme Male Brain Theory ) due to high testosterone levels in the womb could be a risk factor for ASA was specifically investigated in recent studies, but could not be confirmed.

Atypical connectivity

In 2004, a group of researchers led by Marcel Just and Nancy Minshew at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh (USA) discovered the appearance of changed connectivity (large-scale information flow ) in the brain in the group data of 17 test subjects from the Asperger's range of the autism spectrum. Compared to the control group, functional brain scans ( fMRI ) showed both areas of increased and decreased activity and a reduced synchronization of the activity patterns of different brain areas. Based on these results, the authors developed the first time the theory of sub connectivity (underconnectivity) for the explanation of autism spectrum.

The results were confirmed, expanded and refined relatively quickly in further studies, and the concept of sub-connectivity was further developed accordingly. With regard to other theories, it was not presented as a counter-model, but as an overarching general model. In the years that followed, the number of studies of connectivity in the autism spectrum skyrocketed.

In addition to more global sub-connectivity , more local over- connectivity was often found. The latter, however - based on knowledge of early childhood brain development in autism - is understood more as over-specialization and not as an increase in effectiveness. To accommodate both phenomena, the concept is now called atypical connectivity . It is becoming apparent (as of July 2015) that it is establishing itself as a consensus model in research. This also applies when considering the Asperger's part of the autism spectrum in isolation. The atypical connectivity present in the autism spectrum is understood as the cause of the particular behavior observed here, such as in the recording of connections between things, people, feelings and situations.

Environmental and possible combined factors

While the hypothesis that adding thiomersal to vaccines could increase the risk of ASA has been refuted many times (see the following section), the possible influence of other - environmental - increased intake of mercury on the ASA risk is still controversial due to contradicting test results . A 2011 study by Swinburne University in the Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health based on a survey of the grandchildren of survivors of "Rosa Disease" ( Infantile Acrodynia , a brain stem cephalopathy likely to be caused by mercury intoxication with skin and multiple organ symptoms Infants) suggests that a combination of genetic and environmental factors can indeed play a role in the development of autistic symptoms, but only in children with an (innate) preposition for mercury hypersensitivity. The study points out, however, that the autism diagnoses in this study were not confirmed. For further research into a possible connection between autism and mercury poisoning in comparably high amounts, further research into "Rosa Disease" is required. In the 50s, mercury was administered in substantial quantities against childhood diseases, this form of acrodynia has practically disappeared since then. The study apparently neither examined the affected persons themselves nor showed any transferability between acrodynia and other mercury exposure.

Psychoanalytic explanatory approach

The psychoanalyst Bernd Nissen suspected that projective identification as a defense mechanism is involved in the development of autistic disorders . It is assumed in the model that in the early childhood phase of development the hope for a containing object was given up, which can have various causes in the life story. Through psychological encapsulation, self and object relationships are avoided as a result. For protection, a child withdraws his attention from the world in favor of self-generated sensations that are easily predictable and avoid excessive demands that would involve the risk of a dissolution of the personality.

Refuted explanations

Damage caused by incorrect vaccination / vaccines

The rumor keeps cropping up that autism could be caused by vaccinations against mumps , measles or rubella (MMR), whereby an organic mercury compound contained in the vaccine , the preservative thimerosal , is suspected as the triggering substance. Such reports lack "any scientific basis, so the frequency of autism does not differ in vaccinated and unvaccinated children." The connection between vaccines containing thiomersal and autism has meanwhile been refuted by various studies. Regardless of this, vaccines today usually no longer contain thimerosal. As expected, there was no subsequent decrease in the number of new cases - a further weakening of the “autism-through-vaccination” hypothesis .

The belief that autism is a result of vaccine damage was based on a 1998 publication by Andrew Wakefield in The Lancet . In 2004, it was revealed that, prior to the release, Wakefield had received £ 55,000 in third-party funding from attorneys representing parents of autism-affected children . They looked for links between autism and vaccination to sue vaccine manufacturers. The money was not known to either the co-authors or the magazine. Thereupon ten of the thirteen authors of the article resigned from it. In January 2010, the UK General Medical Council ruled that Wakefield had used “unethical research methods” and that its findings were presented in “dishonest” and “irresponsible” ways. The Lancet then withdrew Wakefield's publication entirely. As a result, he was also banned from working in Great Britain in May 2010 .

In September 2006, the American Food and Drug Administration rejected a connection between autism and vaccines as unfounded, and numerous scientific and medical institutions followed this assessment.

Auties and Aspies

The manifestations of autism cover a wide spectrum. Many people with autism want no "cure" because they do not autism as a disease, but as a normal part of their self- regard. Many adults with milder autism have learned to cope with their environment. Instead of being pathologized, they often only want tolerance and acceptance from their fellow human beings. They also do not see autism as something separate from them, but as an integral part of their personality.

The Australian artist and Kanner autist Donna Williams has suggested the term auties in this context , which either refers specifically to people with Kanner autism or generally to all people on the autism spectrum. Williams founded the Autism Network International (ANI) together with Kathy Lissner Grant and Jim Sinclair in 1992 and is considered a co-initiator of the neurodiversity movement . The term aspies for people with Asperger's syndrome comes from the US educational scientist and Asperger's autist Liane Holliday Willey . In their essay The Discovery of Aspie, psychologists Tony Attwood and Carol Gray focus on positive traits in people with Asperger's Syndrome. The terms Auties and Aspies were adopted by many self-help organizations of people on the autism spectrum.

In order to express the desire of many autistic people for acceptance by their fellow human beings, some have been celebrating Autistic Pride Day on June 18 every year since 2005 . The word autism rights movement - " Neurodiversity " (neurodiversity) - brings the idea expressed that an atypical neurological development corresponds to a normal human difference that also deserve acceptance as any other (physiological or other) human variant.

Autism research

In the basic research was in visual perception one over sharp angle attention of autistic noted that in his sharpness ( sharpness thick) with the severity of autistic symptoms correlated , as well as an increased sensitivity to visual fine contrasts.

Clinical observations by Uta Frith (2003) made it clear that people with autism often have considerable difficulties in understanding linguistic utterances appropriately in the given linguistic situation (context). Results from Melanie Eberhardt and Christoph Michael Müller indicated that an autism concept, a detail-oriented processing of language, can explain many peculiarities of speech understanding of autistic people.

Current results of international autism research are presented at the Scientific Conference Autism Spectrum (WTAS), which has taken place annually since 2007 . With the founding of the Scientific Society for Autism Spectrum (WGAS) in 2008, this conference is also its main organ.

The University Center Autism Spectrum (UZAS) in Freiburg is a special research center in German-speaking countries .

Autism and disability

Accessibility

A UN study recognizes the cultural peculiarity of autistic people to form barrier-free online communities as equivalent within the framework of human rights: “Here, the concept of community should not be necessarily limited to a geographic and physical location: some persons with autism have found that support provided online may be more effective, in certain cases, than support received in person. "

Autistic people in Germany have the right to barrier-free telex communication. This can, for example, be taken from a decision of the Federal Social Court of November 14, 2013, which was fought for by the self-help of autistic people for autistic people .

Severe disability

Degree of disability : “The criteria of the definitions of the ICD 10-GM version 2011 must be met. Comorbid mental disorders are to be considered separately. A disability only exists from the beginning of the impairment of participation. A general determination of the GdS after a certain age is not possible.

For profound developmental disorders (especially early childhood autism, atypical autism, Asperger's syndrome)

- without social adjustment difficulties the GdS is 10–20,

- with slight social adjustment difficulties the GdS is 30-40,

- with medium social adjustment difficulties the GdS is 50-70,

- with severe social adjustment difficulties, the GdS is 80–100.

Social adjustment difficulties exist in particular if the ability to integrate into areas of life (such as standard kindergarten, standard school, general labor market, public life, domestic life) is not given without special support or support (for example through integration assistance) or if those affected require supervision over and above the appropriate age. Moderate social adjustment difficulties are particularly prevalent when integration into areas of life is not possible without comprehensive support (e.g. an integration assistant as integration aid). There are severe social adjustment difficulties in particular when integration into areas of life is not possible even with comprehensive support. "

Helplessness : "In the case of profound developmental disorders, which in themselves cause a GdS of at least 50, and in the case of other equally severe behavioral and emotional disorders that begin in childhood with long-lasting, considerable difficulties in classifying, helplessness is generally to be assumed up to the age of 18."

The aforementioned regulations have been in effect since December 23, 2010 and November 5, 2011

Before 2010/2011, autistic people in Germany were automatically classified as severely disabled persons with a degree of disability (GdB) between 50 and 100 according to the earlier indications for medical expert work (AHG) in social compensation law and according to the severely disabled person law Part 2 SGB IX Assumed helplessness to children up to at least 16 years of age .

Autism in the media

Documentation

- My world has a thousand puzzles - the life and thinking of highly gifted autistic people - Documentation as part of the ZDF program 37 Grad , episode 572, Germany 2007, directed by Chiara Sambucchi.

-

Autistic - Documentary by Wolfram Seeger for WDR and 3sat about the Bucken house in Velbert , a privately organized home in which 13 adult autistic people live. Germany 2009 (90 min.).

- Alternative short version: The strange son - In the house of the autistic - u. a. Broadcast as part of the WDR series Menschen closely , 2009 (44 min.).

- Expedition into the brain - 3-part scientific documentary about savants and autistic people with savant abilities, Arte and Radio Bremen , TR-Verlagsunion, 2006, ISBN 3-8058-3772-0 (DVD, German / English, approx. 156 min.).

- Programs of the WDR television magazine Quarks & Co :

- Autism - when thinking makes you lonely. 2006.

- What's different about Nicole? Encounter with an autistic woman. 2008.

- What is autism - Series as part of the school television program Planet Schule des SWR and WDR television

- The Boy With The Incredible Brain - Report on Daniel Tammet as part of the British TV series Extraordinary People. 2005 (English).

- When change is scary. Short film, Germany 2012, director: Christian Landrebe (7 min.)

- Help with Autism? The role of bacteria - Documentation by Marion Gruner and Christopher Sumpton about scientists who are looking for evidence of the cause of the disorder in the human intestinal flora. Canada 2012, Arte (52 min.).

- Ines Schipperges: Autism Series: All eight episodes. In: SZ-Magazin, March 28, 2018. Awarded the DGPPN Media Prize for Science Journalism in the Society category.

Films The following is a list of movies that treat autism as a central theme:

- The Accountant (with Ben Affleck )

- The Mercury Puzzle (with Miko Hughes )

- Rain Man (with Dustin Hoffman )

- Nobody hears the scream (with Bradley Pierce )

- Ben X (with Greg Timmermans )

- Her name is Sabine (with Sabine Bonnaire )

- You are not walking alone (film about the life of Temple Grandin , with Claire Danes )

- My Name Is Khan (with Shah Rukh Khan )

- The cold sky

- Mozart and the Whale (Original title: Mozart and the Whale )

- There Are No Feelings In Space (2011)

- Jimmie (2008)

- Matthijs' rules (Original title: De regels van Matthijs ) (2012)

TV Shows

- Aapki Antara (India, 2009)

- Commissioner Beck - The Boy in the Glass Ball (Sweden, 2001)

- Die Brücke - Transit in den Tod (Sweden / Denmark, 2011; German as ZDF co-production)

- The Good Doctor (United States, 2017)

Radio

- Thomas Gaevert : "I couldn't figure it out" - report from the world of autism. Production: Südwestrundfunk 2005 - 25 minutes; First broadcast: September 21, 2005 on SWR2

literature

Current guidelines

- AWMF - Guideline Autism Spectrum Disorders in Children, Adolescents and Adults, Part 1: Diagnostics. German Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy , as of 2016 ( awmf.org ; valid from 2016 to 2021).

Works of historical importance

- Hans Asperger : The mentally abnormal child. In: Wiener Klinische Wochenzeitschrift. Vol. 51, 1938, ISSN 0043-5325 , pp. 1314-1317.

- Hans Asperger : The "Autistic Psychopaths" in Childhood. In: Archives for Psychiatry and Nervous Diseases. Volume 117, 1944, pp. 73-136. doi: 10.1007 / bf01837709 ( autismus-biberach.com [PDF; 197 kB]).

- Leo Kanner : Autistic disturbances of affective contact. In: Nervous Child. 1943, Vol. 2, pp. 217-250.

- Lorna Wing : Asperger's syndrome. A clinical account. In: Psychological medicine. Volume 11, H. 1, February 1981, ISSN 0033-2917 , pp. 115-129, PMID 7208735 (scientific publication in which the term “Asperger's Syndrome” is used for the first time).

Neurobiology of the autism spectrum

- JO Maximo, EJ Cadena, RK Kana: The implications of brain connectivity in the neuropsychology of autism. In: Neuropsychology review. Volume 24, number 1, March 2014, pp. 16–31, doi: 10.1007 / s11065-014-9250-0 , PMID 24496901 , PMC 4059500 (free full text) (review).

- RA Müller, P. Shih, B. Keehn, JR Deyoe, KM Leyden, DK Shukla: Underconnected, but how? A survey of functional connectivity MRI studies in autism spectrum disorders. In: Cerebral cortex (New York, NY 1991). Volume 21, number 10, October 2011, pp. 2233-2243, doi: 10.1093 / cercor / bhq296 , PMID 21378114 , PMC 3169656 (free full text) (review).

Introductory and advisory literature

- Tony Attwood: Asperger's Syndrome. How you and your child seize all opportunities: the successful practical handbook for parents and therapists. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-8304-3219-4 (English original 1998).

- Vera Bernard-Opitz: Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASS): A practical handbook for therapists, parents and teachers. 3rd, revised. and exp. Edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2015, ISBN 978-3-17-022465-0 .

- Anne Häussler: The TEACCH approach to promoting people with autism - introduction to theory and practice. 5th, improved and enlarged edition. Borgmann, Dortmund 2016, ISBN 978-3-8080-0771-6 .

- Inge Kamp-Becker, Sven Bölte: Autism. 2nd Edition. Reinhardt, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-8252-4153-7 .

- Joan Matthews and James Williams: I'm special! Autism and Asperger's. The self-help book for children and their parents. Trias, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-89373-668-9 .

- Fritz Poustka et al. a .: Guide to autistic disorders. Information for those affected, parents, teachers and educators. Hogrefe, Göttingen u. a. 2004, ISBN 3-8017-1633-3 .

- Christine Preißmann : Autism and Health: Recognizing Special Features - Overcoming Hurdles - Promoting Resources. W. Kohlhammer, 2017, ISBN 978-3-17-032027-7

- Helmut Remschmidt : Autism. Manifestations, causes, aids ( Beck series. Volume 2147). 5th updated edition. Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-57680-5 , urn : nbn: de: 101: 1-201304119594 .

- Brita Schirmer: Parents Guide to Autism. How your child experiences the world. Promote effectively with targeted therapies. Mastering difficult everyday situations. Trias, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-8304-3331-X .

- Judith Sinzig: Early Childhood Autism. Springer-Verlag, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-642-13070-0 ; doi: 10.1007 / 978-3-642-13071-7 .

- Kristin Snippe: Autism. Ways in the language. Schulz-Kirchner-Verlag, Idstein 2013, ISBN 978-3-8248-0999-8 .

- Peter Vermeulen: That's the title: About autistic thinking. Bosch & Suykerbuyk, Arnhem 2009, ISBN 978-90-79122-03-5 .

- Siegfried Walter: Autism. Appearance, causes and treatment options. Persen, Horneburg 2001, ISBN 3-89358-809-4 .

- Michaela Weiß: Autism. A comparison of therapies. A handbook for therapists and parents. Edition Marhold, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-89166-997-6 .

Web links

- Michael Cundall: Autism. In: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Without date (English).

- Database: Autism Data. National Autistic Society (articles, books, videos, and other materials on autism).

- Video of Amazing Things Happen: Amazing things happen on YouTube, May 11, 2017 (5:30 minutes, English).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Guideline on Autism Spectrum Disorders in Children, Adolescents and Adults, Part 1: Diagnostics. Long version p. 14f . See A.2.2 Classification of Autism Spectrum Disorders and A.2.3 Autism Spectrum Disorders as a dimensional disorder. Status 2016, Working Group of Scientific Medical Societies .

- ↑ a b c ICD-11 Implementation Version - who.int, accessed June 2018.

- ↑ DIMDI entry.Retrieved September 17, 2019

- ↑ a b Uwe Henrik Peters (2007): Dictionary of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology. 6th edition. Fischer at Elsevier, ISBN 978-3-437-15061-6 . See Autism (page 58) .

- ^ Sigmund Freud: mass psychology and ego analysis. In: GW. XIII, p. 73 f.

- ↑ Anna M. Ehret, Matthias Berking: DSM-IV and DSM-5: What has actually changed? In: behavior therapy. 23, 2013, pp. 258–266, doi: 10.1159 / 000356537 (free full text).

- ↑ a b DSM-5 Autism Spectrum Disorder, 299.00 (F84.0), Diagnostic Criteria. In: autismspeaks.org, accessed December 3, 2015.

- Jump up ↑ S. Tordjman, MP Celume, L. Denis, T. Motillon, G. Keromnes: Reframing schizophrenia and autism as bodily self-consciousness disorders leading to a deficit of theory of mind and empathy with social communication impairments. In: Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. Volume 103, 08 2019, pp. 401-413, doi : 10.1016 / j.neubiorev.2019.04.007 , PMID 31029711 (review).

- ^ Root (pseudonym): autism. ( Memento of November 21, 2011 in the Internet Archive ). In: Behindertenecke.de. September 5, 2006, accessed March 5, 2020.

- ↑ Book summary ( memento of October 17, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) on Dion E. Betts and Stacey W. Betts: Yoga for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. A Step-by-Step Guide for Parents and Caregivers. 2006, ISBN 1-84310-817-8 . In: jkp.com, accessed January 28, 2020.

- ↑ The expression was coined in 1971 by an American research team: MK DeMyer, DW Churchill, W. Pontius, KM Gilkey: A comparison of five diagnostic systems for childhood schizophrenia and infantile autism. In: Journal of autism and childhood schizophrenia. Volume 1, Number 2, April-June 1971, pp. 175-189, PMID 5172391 . Reviewed in: MK DeMyer, JN Hingtgen, RK Jackson: Infantile autism reviewed: a decade of research. In: Schizophrenia bulletin. Volume 7, Number 3, 1981, pp. 388-451, PMID 6116276 , (free full text) (review).

- ↑ M. Dawson, I. Soulières, MA Gernsbacher, L. Mottron: The level and nature of autistic intelligence. In: Psychological science. Volume 18, number 8, August 2007, pp. 657-662, doi: 10.1111 / j.1467-9280.2007.01954.x , PMID 17680932 , PMC 4287210 (free full text).

- ^ C. Kasari, N. Brady, C. Lord, H. Tager-Flusberg: Assessing the minimally verbal school-aged child with autism spectrum disorder. In: Autism research. Official journal of the International Society for Autism Research. Volume 6, number 6, December 2013, pp. 479-493, doi: 10.1002 / aur.1334 , PMID 24353165 , PMC 4139180 (free full text) (review).