Johann I (Brandenburg)

Johann I (* around 1213; † after June 3, 1266 ) was together with his brother Otto III from 1220 until his death . the pious , Margrave of the Mark Brandenburg .

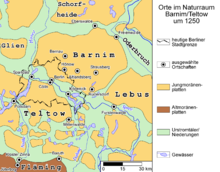

The reign of the two Ascanian margraves was characterized by the extensive land development to the east, which included the last parts of the Teltow and Barnims , the Uckermark , the Stargard region , the Lebus region and the first parts east of the Oder in the Neumark . They were able to sustainably consolidate the domestic political importance and position of the Mark Brandenburg in the Holy Roman Empire , which was expressed, among other things, in the fact that Johann's brother Otto was a candidate for the occupation of the royal throne in the empire in 1256. They also founded various cities and made a special contribution to the development of the two Berlin founding cities, Cölln and Berlin . They expanded the neighboring Ascanian castle in Spandau into their preferred residence.

Even before her death, they shared the mark in the course of Erbregelungen in the Johannine and Otto Linie and donated in 1258 under the name Mariensee the Cistercian - Kloster Chorin because the traditional askanische grave lay Lehnin remained with the Ottonian line. After the Ottonians died out in 1317, the two parts of the country came together again under Johann's grandson Waldemar .

Life

Time of guardianship

Johann was the older son of Albrecht II of Brandenburg from the Ascanians and Mathilde (Mechthild) from Lausitz, daughter of Count Konrad II von Groitzsch from a side branch of the Wettins .

Since both Johann and his two years younger brother Otto were minors when their father died in 1220, Emperor Friedrich II transferred the feudal guardianship to Archbishop Albrecht I of Magdeburg ; the guardianship exercised Count Heinrich I von Anhalt , the older brother Duke Albrecht I of Saxony and cousin Albrechts II. As the sons of Duke Bernhard of Saxony, both were the closest relatives on his father's side, with Heinrich having the older rights.

In 1221 the mother, Countess Mathilde, bought the feudal guardianship from the Magdeburg Archbishop against 1900 Mark Magdeburg silver and then ruled together with Heinrich I instead of their sons. When the Archbishop of Magdeburg traveled to Emperor Friedrich II in Italy soon afterwards, Duke of Saxony Albrecht tried to take advantage of the situation, which led to a falling out with his brother Heinrich I. The Saxon attacks prompted Mechthild's brother-in-law, Count Heinrich I of Braunschweig-Lüneburg, to intervene. Frederick II, an uncle on his mother's side, prevented an open feud and called on the Saxon-Anhalt brothers to keep the peace.

Probably since the death of their mother in 1225, the brothers exercised the feudal rule over the Mark Brandenburg together; at this point in time they were probably between the ages of twelve (Johann I) and ten (Otto III). In 1231 they are said to have received the sword line in the Neustadt Brandenburg - this year is considered to be the official beginning of their reign.

Domestic politics

After the death of Count Heinrich von Braunschweig-Lüneburg (1227), the brothers supported his nephew, their brother-in-law Otto the child , who was only able to assert himself against Hohenstaufen claims and his own ministerials by force of arms. In 1229 there was a feud with the former feudal guardian Archbishop Albrecht, which was peacefully ended. Like their previous adversaries and defenders, they appeared at the Reichstag in Mainz in 1235, where the Peace of Mainz was proclaimed.

After the disputes over the royal rule of Conrad IV and Heinrich Raspes , they declared their recognition to King Wilhelm of Holland in 1251 ; In 1257 they exercised the Brandenburg Kurrecht for the first time in the election of Alfonso X of Castile. 1256 was Otto III. (also: Otto the Pious) one of the contenders for royal dignity. Although he did not become king, the candidacy expresses the increased domestic political importance that the Mark, founded in 1157 by Albrecht the Bear , had gained under the reign of the brothers. In the first few years the mark was hardly perceived as an independent principality, but in the 1230s / 1240s it was finally given the office of Reich treasurer. The participation of the margraves in the election of the German head of the empire was considered indispensable since the middle of the 13th century.

Land expansion

Together with his brother, Johann I expanded the area of the margraviate and developed market towns or castle locations such as Spandau , Cölln , Berlin , and Prenzlau into central locations or cities. This also included Frankfurt / Oder , which Johann I elevated to the status of city in 1253 after sending a locator .

Teltow War and Treaty of Landin

The last parts of the Barnims and the southern Uckermark up to the Welse came to the Mark Brandenburg in 1230/1245. On June 20, 1236, in the Treaty of Kremmen , the two margraves acquired the land of Stargard together with the owner and Wustrow from Duke Wartislaw III. from Pomerania. In the same year, 1236, the Ascanians began building Stargard Castle to secure their northernmost parts of the country .

Although it is located close to Berlin-Cölln and is now a part of Berlin, the former headquarters of the Sprewanen, the Slavic Koepenick Castle ( Copnic = island town ) at the confluence of the Spree and Dahme rivers , did not come through until 1245 after a seven-year battle for the Barnim and the Teltow against the Meißner Wettin under the Ascanian rule. After this Teltow War , the Wettin fortress in Mittenwalde was also owned by the margraves, who subsequently expanded their rule further east. In 1249 the Ascanian possessions reached the Oder with parts of the Lebus region .

When in 1250 the Pomeranian dukes had ceded the northern Uckermark ( Terra uckra ) to the Welse, Randow and Löcknitz in an exchange for half of the Wolgast region to the Ascanians in the Treaty of Landin , Johann I. and Otto III. The basis for the German settlement of the Terra trans Oderam was finally created. In this exchange they benefited from the marriage policy , because Johann’s first wife Sophia, the daughter of King Waldemar II of Denmark , had brought half of Wolgast into the marriage as a dowry in 1230 . The Landin Treaty of 1250 is considered the Uckermark to be born.

Neumark and Stabilization Policy

In the first third of the 13th century, German settlers were recruited by Duke Leszek I to settle what would later become Neumark . With his death in 1227, the Polish central power finally fell into disrepair, which gave the Margrave Brothers the opportunity to expand eastwards. By acquiring land, they crossed the Oder and expanded their domain further east to the Drage River and north to the Persante River . In 1257, Margrave Johann I. founded Landsberg as a river crossing on the Warthe shortly before the previous pass near Zantoch in order to deduct the considerable income from long-distance trade (customs, fees from market operations and the right to defeat) from this Polish place (based on the parallel example of Berlin as a counter-foundation to Köpenick ). In 1261 the margraves of the Knights Templar bought the town of Soldin , which developed into the power center of the Neumark .

To stabilize the new parts of the country, the two margraves resorted to the tried and tested Ascanian means of founding monasteries and settlements. As early as 1230, they supported the founding of the Cistercian monastery Paradies by the Polish Count Nicolaus Bronisius near Międzyrzecz ( Meseritz ) as a filiation of Lehnin. The connection with the Polish count served to secure the border against Pomerania and prepared the economic takeover of this part of the Neumarkt. For example, the later aristocratic family Sydow came to the new market as settlers . In the west of today's Polish West Pomeranian Voivodeship , they enfeoffed the von Jagow family with the small town of Zehden .

Stefan Warnatsch sums up the development of the country and the Ascanians' push towards the Baltic Sea , the middle Oder and the Uckermark as follows: “ The great success of the expansion of the rule in the 13th century was primarily due to the great-grandchildren Albrecht the Bear [...]. In terms of space and concept, they went much further than their predecessors in their concept of rule. "According to Lutz Partenheimer, " the Ascanians [around 1250] had pushed their Magdeburg, Wettin, Mecklenburg, Pomeranian, Polish and smaller competitors back on all fronts. “However, Johann I. and Otto III. the strategically important connection to the Baltic Sea, which they wanted to reach by bypassing Pomerania along the Oder and later through the Neumark, did not establish.

Development of the Berlin area

The development of the Berlin area is closely linked to the politics of the two margraves. While the two founding cities of Berlin (Cölln and Berlin) are relatively late foundings from around 1230/1240 (more recent analyzes 1170/1200, see below), today's Berlin town centers Spandau and Köpenick already existed as ramparts in Slavic times (around 720) and thus naturally had a greater strategic and political importance than the merchant branches in Berlin and Cölln, which only emerged from around 1170. The border between the Slavic tribes of the Heveller and Sprewanen ran through the middle of today's Berlin for a long time. As the eastern outpost of the Heveller under Pribislaw-Heinrich, Spandau was already connected to the Mark around 1130, albeit only very indirectly, through a contract of inheritance (which only became due in 1150) between Albrecht the Bear and Pribislaw-Heinrich , while Köpenick was not finally added until 1245.

Spandau residence

After a battle on Plauer See near their Brandenburg an der Havel residence , which they lost in 1229 to troops of the Archbishop of Magdeburg, their former feudal guardian, the margraves had to flee to their Spandau castle because the Brandenburgers had to flee because of the Magdeburgers who were immediately following refused to open the city gates. In the following years the brothers made Spandau - next to Tangermünde in the Altmark - their preferred residence. So between 1232 and 1266 there are seventeen documented stays in Spandau alone, more than at any other place.

Already before or shortly after his victory against Jaxa (probably Jaxa von Köpenick ) in 1157, Albrecht the Bear had very probably had the Slavic facility on the Burgwallinsel expanded to secure the border to the east. Towards the end of the century, the Askanians probably relocated their castle around a kilometer north to the area of today's Spandau Citadel because of the rising water table . Proof of an Ascanian castle can be considered certain for 1197. Johann I and his brother expanded the facility and promoted the civitas (city rights since 1232 at the latest) with many measures, including the richly endowed foundation of the Benedictine St. Mary's nunnery in 1239. Nonnendammallee , one of the oldest streets in Berlin and as Nonnendamm already in the 13th century part of a trade route , reminds of the monastery.

Expansion of Cölln and Berlin

For the areas of the neighboring towns of Berlin and Cölln, which are separated by the Spree , according to the current state of research, there is not the slightest indication of a city-like Slavic settlement, contrary to what is stated . Only in the Slavic-German transition period did the Berlin ford gain in importance through the largely swampy Berlin glacial valley , when Johann I and Otto III. the Teltow and Barnim plateaus, which had previously been sparsely populated in the Berlin area, were settled with Slavs from the area and German immigrants.

According to Adriaan von Müller , the strategic importance of Cölln and Berlin and the reason for the founding was very likely to form and secure a counterpoint to the Wettin trading hub Köpenick with its own trade routes to the north and east. The wide ford across two or even three river arms could best be protected with two fortified neighboring settlements. The north-western Teltow was secured by the margraves by the settlement of the Templar Order , who protected the new trade route from the Halle area through a chain of villages with today's Berlin districts Marienfelde , Mariendorf , Rixdorf and Tempelhof . After the Wettins had been defeated in the Teltow War in 1245 and Köpenick had become Ascanic, Köpenick's importance steadily declined, while Berlin and Cölln assumed an increasingly central position in the trading network of the new areas.

For Winfried Schich, it is largely certain “ that Berlin and Cölln owed their development as urban settlements to the structural changes in this area during the period of the high medieval state expansion, which on the one hand led to a densification of rural settlement and on the other hand resulted in a reorganization of long-distance trade routes. […] During the reign of the Margraves Johann I and Otto III. [... /] the dilluvial plateaus of the Teltow and Barnim with their heavy and comparatively fertile soils were settled according to plan and taken under the plow. “In the first settlement phase, on the other hand, the areas of the lowlands and bodies of water with their lighter soils were preferred places of settlement.

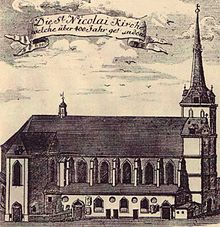

According to the Chronica Marchionum Brandenburgensium from 1280, Johann I and Otto III. Berlin and other places built ( exstruxerunt ). Since they took up their margrave office in 1225, the period around 1230 has been considered the founding period of Berlin. More recent archaeological research has shown traces of settlement of a presumed market town for both core parts of Berlin as early as the end of the 12th century. After 90 graves have been uncovered on the oldest building in Berlin, the Nikolaikirche with foundation walls from 1220/30, there are also dates to the last quarter of the 12th century. The two margraves cannot therefore be regarded as the founding fathers of Berlin, but they played a decisive role in the expansion of the city and privileged the expansion ( extructio loci ) by 1240 at the latest.

In addition to the transfer of the Brandenburg law (including customs exemptions, free exercise of trade and commerce, hereditary property rights), above all the privilege of defeat in favor of the twin cities, which was issued by the two margraves and which made a decisive contribution to the economic situation of Berlin-Cölln The cities of Spandau and Köpenick. This included measures such as the transfer of the Mirica , the Cöllnische Heide , with all rights of use to the citizens of Cölln. The connection between the margraves and Berlin is expressed not least in the choice of their confessor Hermann von Langele. Hermann was the first member of the Berlin Franciscan Convent known by name and appears as a witness in a document issued by the Margraves in Spandau in 1257.

Distribution of inheritance and offspring

The common rule of the margraves ended in 1258/60; a clever division of the rulers and continued consensual policy prevented the margraviate from falling apart. The preparations for the reorganization had probably already started in 1250 after the final acquisition of the Uckermark, but at the latest in 1255 after the marriage of Johann I to Jutta (Brigitte), a daughter of Duke Albrecht I of Saxony-Wittenberg .

Johannine and Ottonian lines

Chorin Monastery - burial place and power politics

The marriage policy and the division of sovereignty in 1258 led to the joint foundation of the Mariensee Monastery on a former island in Lake Parstein on the northeastern edge of today's Barnim district for the Johannine line, as the Lehnin family monastery was to remain with the Ottonian line. The construction of the monastery began in 1258 by monks from Lehnin. Even before completion, it was relocated around eight kilometers to the southwest in 1273 with the new name Kloster Chorin . After his death in 1266, Johann I was buried in the new Mariensee monastery and after 1273 he was reburied in Chorin. Johann I is said to have ordered the relocation of the monastery in the year of his death and to have given the planned Chorin monastery rich donations, including the village of Parstein , on his deathbed . His sons later confirmed these donations for the salvation of their father's soul and for their own at the same time.

As with all Ascanian monasteries, economic and power-political considerations played an important role in addition to the pastoral aspects. Because to the west of the monastery there was a Slavic ring wall on the island in Lake Parstein , which Johann I and his brother very likely used as a tower castle against the Pomeranian rivals. The monastery was supposed to take over central and dominant functions. “ Both the establishment itself and its location in an old regional center 'across' the traffic routes […] in populated areas are the ruler's power-political calculations. "

- For the economic-political aspects of the Ascanian monastery founding see in detail: Kloster Lehnin

Division of the country

The division of the state awarded Johann I and his descendants Stendal with the Altmark , which belonged to the Mark as the cradle of Brandenburg until 1806, as well as the Havelland and the Uckermark, among others , while his brother Otto sat in Brandenburg / Spandau and Salzwedel and the Barnim, the Land Lebus and Land Stargard ruled. The income and the number of vassals were in the foreground in this division, while geographical considerations played only a subordinate role. The successors of Johann I and Otto III. as Margraves of Brandenburg , Otto IV. ( with the arrow ) , Waldemar ( the great ) and Heinrich II., ( the child ) all came from the Johannine line. The sons and grandsons of Otto and the other descendants of Johann also had the title of margrave and in this function - like Johann's sons Johann II. And Conrad I in 1273 as co-signers of the deed to relocate the monastery to Chorin - notarized various businesses, but remained " Co-regents ".

In 1317 the Ottonian line ended with the death of Margrave Ludwig in Spandau, so that the last great Ascanian Margrave Waldemar reunited both lines in the same year. Only three years later the Johannine line died out and in 1320 the Ascanian rule in Brandenburg ended. In 1290 19 margraves of both lines had gathered on a mountain near Rathenow , in 1318 only Waldemar and Heinrich the child were still alive. The last Ascanian in Brandenburg, Heinrich II. The child († 1320), played only an insignificant role in his two "years of reign" as an eleven-year-old in 1319/1320 and was already the plaything of the interests of various houses that were pushing into the power vacuum.

Family, offspring

Johann married

- 1235 (betrothal 1230) Sophia (1217–1247), the daughter of King Waldemar II of Denmark ( house Estridsson ) and Berengarias of Portugal ,

- 1255 Jutta (Brigitte) (? –1266), daughter of Duke Albrecht I of Saxony and Agnes of Austria (1206–1226).

Children with Sophia from Denmark:

- Johann II. (1237 (?) - 1281), co-regent as Margrave of Brandenburg

- Otto IV “with the arrow” (approx. 1238–1308), Margrave of Brandenburg

- Konrad I (approx. 1240–1304), co-regent as Margrave of Brandenburg, father of the last great Brandenburg Ascanian, Margrave Waldemar

- Helene (1241/42 –1304), married to Margrave Dietrich von Landsberg since 1258 , (1242–1285)

- Erich (approx. 1242–1295), Archbishop of Magdeburg 1283–1295

Children with Jutta von Sachsen:

- Agnes (after 1255–1304), married to King Erich V. Glipping of Denmark (1249–1286) since 1273, married to Gerhard II (1254–1312) since 1293, Count von Holstein-Plön between 1290 and 1312

- Heinrich I “without land” (1256–1318), Margrave of Landsberg

- Mechthild (? –Before 1309), married to Duke Bogislaw IV of Pomerania , (1258–1309)

- Albrecht (approx. 1258–1290)

- Hermann (? –1291), since 1290 Bishop of Havelberg

Between 1261 and 1264, John I held the Danish King Erich V prisoner, who married his daughter Agnes in 1273 .

After the death of Otto III. , who had ruled alone in 1266/67, took over Otto "with the arrow", from the Johannine line, as Otto IV , although after Johann II only the second oldest Brandenburg-Ascanian scion, the leadership among his numerous, as co-regents acting brothers and half-brothers and, as the ruling margrave, mainly determined the fate of Brandenburg.

Memorial, poem

Double statue of the brothers in Berlin's Siegesallee

The double statue shown was in the former Siegesallee in the Tiergarten in Berlin , the "splendid boulevard" commissioned by Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1895 with monuments from the history of Brandenburg and Prussia. Between 1895 and 1901, under the direction of Reinhold Begas , 27 sculptors created 32 statues of the Brandenburg and Prussian rulers, each 2.75 m high. Each statue was flanked by two smaller busts depicting people who had played an important role in the life of the respective ruler or in the history of Brandenburg / Prussia.

For monument group 5 , these were the busts of Provost Simeon von Cölln and Marsilius . Simeon is named on October 28, 1237 together with Johann I and Bishop Gernand von Brandenburg as a witness in Cölln's first document. Marsilius was the first proven mayor of Cölln and Berlin and was responsible for both places at the same time.

The choice of the secular and ecclesiastical head of Berlin-Cölln as secondary characters underscores the close ties between the margravial brothers and the city of Berlin, also in the view of history of Reinhold Koser , the historical director of Siegesallee. Koser regarded the founding or expansion of the later capital as the most important merit of the margraves and placed them above the state expansion and the founding of a monastery. He was also impressed by the consensual joint government of the brothers, as presented in the chronicle of 1280. According to Koser's instructions, the sculptor Max Baumbach decided to forego the representation of the land reclamation and the monastery foundation and to make the foundation of Berlin the central theme of the double statue.

Johann I, seated on a stone, has spread the document over his knees that is said to have given Berlin and Cölln city rights. The younger Otto III. stands next to him and points with one arm at the certificate, while the other arm rests on a hunting spear. “ Otto's outstretched arms and lowered head suggest protection and support for the city by the brothers. The fact that the young city founders are portrayed here as mature men seemed to Koser legitimized by the right to artistic freedom. “Two boys could not have adequately expressed the founding act of a future cosmopolitan city from the perspective of the current interpretation of history.

While the overall architecture of the group is in the Romanesque style, according to Uta Lehnert the two bank eagles show forms of the strict Art Nouveau .

poem

The philosopher, poet and philologist Otto Friedrich Gruppe (1804–1876) wrote the following verses about the two margraves:

|

Johann and Otto of Brandenburg Many a bloody picture covers the tables of history, |

Who boldly set foot in Germany towards tomorrow? |

Sources, literature, web links, footnotes

Web links

Footnotes

- ↑ Stefan Warnatsch: History of the Lehnin Monastery ... , p. 62

- ↑ Marca Brandenburgensis brandenburg1260.de

- ↑ a b Lutz Partenheimer: Albrecht the Bear ... , p. 195

- ↑ Uwe Michas: The conquest and settlement ... , p. 41

- ↑ Stefan Warnatsch: History of the Lehnin Monastery ... , p. 26

- ^ Wolfgang Fritze: founding city Berlin. The beginnings of Berlin-Cölln as a research problem. Potsdam 2000 ISBN 3-932981-33-2 . A distinction must be made between the beginning of the settlement around 1170 and the granting of city rights around 1240.

- ↑ Stefan Warnatsch: History of the Lehnin Monastery ... , p. 63

- ↑ Felix Escher: The change in the residence function. ... , p. 161

- ↑ Although it is common historiography, it is not completely certain whether Jaxa, who was fighting with Albrecht the Bear in 1157, and Jaxa von Köpenick were the same person. See Jaxa von Köpenick .

- ↑ Winfried Schich: The emergence of the medieval city of Spandau. ..., p. 63f

- ↑ Nonnendammallee. In: Street name lexicon of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein (near Kaupert )

- ↑ Winfried Schich: The medieval Berlin , ... p. 151.

- ^ Adriaan von Müller: Secured traces ..., p. 114f

- ↑ Winfried Schich: The medieval Berlin , ... p. 157.

- ↑ Winfried Schich: The Middle Ages Berlin , ... S. 142ff, 159.

- ↑ However, according to Schich, the underlying document from 1298, with which co-regent Otto V. ( The Tall One ) confirmed the right to defeat (allegedly) granted by his father and uncle, was in part later forged. Nevertheless, this right should actually be granted by Johann I and Otto III. have been awarded. (Winfried Schich: Medieval Berlin , ... p. 160f)

- ↑ Winfried Schich: The emergence of the medieval city of Spandau. ..., p. 83

- ↑ Stefan Warnatsch: History of the Lehnin Monastery ... , p. 64f

- ↑ Harald Schwillus, Stefan Beier: Cistercians between ... , pp. 11, 16

- ↑ Wolfgang Erdmann: Cistercian Abbey Chorin. ... , p. 10

- ↑ Wolfgang Erdmann: Cistercian Abbey Chorin. ... , p. 7

- ↑ The information on the division of the country is sometimes very contradictory. So it says on the Marca Brandenburgensis about Johann I and Otto III in the chapter Your wives and their children : “ The (older) Ottonian line fell the Stendal area in the Altmark, the Havelland, Teltow and Barnim, parts of the Neumark as well as the cities of Brandenburg (Old town), Berlin and Spandau too. "

- ↑ Uwe Michas: The Conquest and Settlement ... , p. 58

- ↑ Stefan Warnatsch: History of the Lehnin Monastery ... , p. 66

- ↑ October 28 (year 1237) in: Daily facts of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein (at the DHM )

- ↑ Winfried Schich: The medieval Berlin , ... p. 141.

- ↑ Uta Lehnert: The Kaiser and ... , p. 115

- ↑ ibid

- ^ Otto Friedrich Grupe: Johann and Otto von Brandenburg . Reproduced from: Georg Sello (Ed.): Hie gut Brandenburg alleweg! Historical and cultural images from the past of the Mark and from old Berlin up to the death of the Great Elector. Verlag von W. Pauli's Nachf., Berlin 1900, pp. 90f. Spelling according to the original.

Sources, literature

Source collection

- Heinrici de Antwerpe: Can. Brandenburg., Tractatus de urbe Brandenburg ( Memento from February 21, 2013 in the Internet Archive ). New ed. and explained by Georg Sello . In: 22nd annual report of the Altmark Association for Patriotic History and Industry in Salzwedel. Magdeburg 1888, issue 1, pp. 3-35. (Internet publication by Tilo Köhn with transcriptions and translations.)

- Chronica Marchionum Brandenburgensium , ed. G. Sello, FBPrG I , 1888.

Bibliographies

- Schreckbach: Bibliogr. for business der Mark Brandenburg , Vol. 1–5 (Publications of the Potsdam State Archives; Vol. 8 ff.), Böhlau, Cologne 1970–1986.

Secondary literature

- Tilo Köhn (Ed.): Brandenburg, Anhalt and Thuringia in the Middle Ages. Ascanians and Ludovingians building princely territorial rule . Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 1997, ISBN 3-412-02497-X

- Helmut Assing : The early Ascanians and their wives. Kulturstiftung Bernburg, 2002, ISBN 3-9805532-9-9 .

- Wolfgang Erdmann : Cistercian Abbey Chorin. History, architecture, cult and piety, prince claims and self-portrayal, monastic economics and interactions with the medieval environment. With the collaboration of Gisela Gooß, Manfred Krause u. Gunther Nisch. With a detailed bibliography. Koenigstein i. Ts. 1994, ISBN 3-7845-0352-7 (= The Blue Books).

- Felix Escher : The change in the residence function. On the relationship between Spandau and Berlin. The margravial court camp in Ascanian times. In: Wolfgang Ribbe (ed.): Slavic castle, state fortress, industrial center. Studies on the history of the city and district of Spandau. Colloqium-Verlag, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-7678-0593-6 .

- Otto von Heinemann : Johann I, Margrave of Brandenburg . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 14, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1881, pp. 151-153.

- Uta Lehnert: The Kaiser and the Siegesallee. Réclame Royale . Dietrich Reimer Verlag, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-496-01189-0 .

- Uwe Michas: The conquest and settlement of northeast Brandenburg. In the series: Discoveries along the Märkische Eiszeitstraße , Volume 7. Society for the research and promotion of the Märkische Eiszeitstraße (Ed.), Eberswalde 2003, ISSN 0340-3718 .

- Adriaan von Müller : Secured Traces. From the early past of the Mark Brandenburg . Bruno Hessling Verlag, Berlin 1972, ISBN 3-7769-0132-2

- Lutz Partenheimer : Albrecht the Bear - founder of the Mark Brandenburg and the Principality of Anhalt. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2001, ISBN 3-412-16302-3 .

- Jörg Rogge: The Wettins. Thorbecke Verlag, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-7995-0151-7 .

- Winfried Schich : The medieval Berlin (1237-1411) . In: Wolfgang Ribbe (Ed.), Publication of the Historical Commission in Berlin: History of Berlin . 1. Volume, Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-406-31591-7 .

- Winfried Schich: The Development of the Medieval City of Spandau . In: Wolfgang Ribbe (ed.): Slavic castle, state fortress, industrial center. Studies on the history of the city and district of Spandau. Colloqium-Verlag, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-7678-0593-6 .

- Johannes Schultze: Johann I .. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 10, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1974, ISBN 3-428-00191-5 , p. 472 ( digitized version ).

- Oskar Schwebel: The Margraves Johann I and Otto III. In: Richard George (Hrsg.): Hie good Brandenburg all way! Historical and cultural images from the past of the Mark and from old Berlin up to the death of the Great Elector. Verlag von W. Pauli's Nachf., Berlin 1900, digitization

- Harald Schwillus, Stefan Beier: Cistercians between order ideal and sovereigns . More-Verlag, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-87554-321-1 .

- Otto Tschirch : History of the Chur and capital Brandenburg ad Havel. Festschrift for the city's millennium in 1928/29 . 2 volumes. Brandenburg an der Havel 1928; 2nd edition 1936; 3rd edition 1941.

- Stephan Warnatsch: History of the Lehnin Monastery 1180–1542 . Studies on the history, art and culture of the Cistercians, Volume 12.1. Lukas Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-931836-45-2 (also: Berlin, Free University, dissertation, 1999).

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Albrecht II. |

Margrave of Brandenburg 1220–1266 |

Otto III. |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Johann I. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Margrave of the Mark Brandenburg |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1213 |

| DATE OF DEATH | after June 3, 1266 |