Óscar Romero

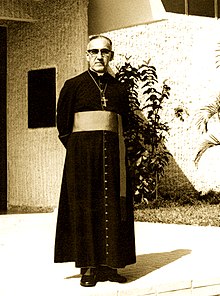

Óscar Arnulfo Romero y Galdámez (born August 15, 1917 in Ciudad Barrios , El Salvador , † March 24, 1980 in San Salvador ) was Archbishop of San Salvador . He stood up for social justice and political reforms in his country and stood in opposition to the military dictatorship in El Salvador at the time. He is considered one of the most prominent advocates of liberation theology .

Romero was shot and killed by a soldier charged with the murder by the Fuerza Armada de El Salvador during a mass he was celebrating in a hospital chapel in San Salvador . His death marked the beginning of the civil war in El Salvador .

On May 23, 2015 Pope Francis Óscar Romero beatified in San Salvador and canonized in Rome on October 14, 2018 .

Live and act

Childhood and studies

Romero was born in 1917 in a small mountain town on the eastern border with Honduras and grew up in modest circumstances. His parents were Santos Romero and Guadalupe de Jesús Galdámez. He had six siblings: the older brother Gustavo and the younger Zaída, Rómulo († 1939), Mamerto, Arnoldo and Gaspar. Arminta died in childbirth. He also had at least one illegitimate sister.

At the age of 13, he entered the San Miguel Seminary as a boarding school student . He began his theology studies in 1937 at the Jesuit seminary in San Salvador . That year his father died. He finished his studies on the instructions of his bishop at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome , where he obtained his degree in theology cum laude in 1941 and received the sacrament of ordination on April 4, 1942 .

In 1943 Romero broke off his doctoral studies in ascetic theology on Christian perfection in the various classes after Luis de la Puente in Rome. He returned to El Salvador in August 1943, again at the request of his bishop. Because he was traveling on an Italian ship, he and his companion Valladares were arrested and interned in Cuba. At the instigation of some Redemptorist Fathers , their onward journey via Mexico to El Salvador was approved, where they received a public reception.

Return and ordination

In the following years he worked as a pastor and editor of church magazines in San Miguel. He became a sought-after preacher far beyond the city. In the late 1960s, virtually all lay movements centered on his parish at San Miguel Cathedral . His work was mainly controversial among Freemasons and Protestants .

On April 4, 1967, he received the title of Monsignor and was soon called General Secretary of the National Bishops' Conference . He therefore left San Miguel and went to San Salvador, having celebrated his last mass on September 1, 1967. On April 25, 1970 Pope Paul VI appointed him . as titular bishop of Tambeae and auxiliary bishop in the Archdiocese of San Salvador . He received the episcopal ordination on June 21, 1970 by the then Apostolic Nuncio in El Salvador and Guatemala, Archbishop Girolamo Prigione ; Co- consecrators were the Archbishop of San Salvador Luis Chávez y González and Bishop Arturo Rivera y Damas . In San Salvador, Bishop Romero ran a conservative newspaper.

Appointment as archbishop

On October 15, 1974, he was appointed Bishop of the Diocese of Santiago de Maria and on February 3, 1977, Archbishop of San Salvador, succeeding Luis Chávez y González. Romero was considered one of the preferred candidates of the conservatives and oligarchs when he was appointed . In the clergy, however, who would have preferred his successor Arturo Rivera y Damas , his appointment was controversial.

His appointment was preceded by a violent internal political conflict over agrarian reform . A commission convened by parliament had drafted reform proposals for a more social redistribution of goods in oligarchically organized agriculture. The commission was dissolved by decree by Mario Molina . As a result of Romero's appointment, there were several attacks on priests. Some were expelled from the country , some under the influence of torture . Attacks on ecclesiastical printing works and houses continued. A controversial election took place on February 20, 1977; triggered by repression at the ballot boxes, a general strike threatened .

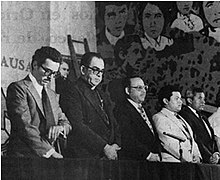

The requirements of the Second Vatican Council , d. H. The guidelines, which were also confirmed by the 2nd General Assembly of the Latin American Episcopate in Medellín , also created an area of conflict in church politics. According to them, the “Church sees itself as a people of God and identifies itself with the sufferings and hopes of the people, especially the oppressed. [...] For this reason, the Church is also destined to turn as a subversive institution against a social order based on injustice, exploitation and oppression. ”The bishops in El Salvador were on the question of how far they should incorporate these liberation theological paradigms into theirs To take over pastoral practice, split into the camp around Romero and Rivera on the one hand and the camp around Walter Antonio Álvarez and Bishop Pedro Arnoldo Aparicio on the other .

Archdiocese under Romero

On Monday, February 28, 1977, security forces and the military shot at a march of demonstrators in the Plaza de la Libertad against the election, which had been fraudulent a week ago and up to 50,000 people had gathered. According to official reports, six and eight people respectively died; according to other estimates, there were up to three hundred fatalities.

The reprisals against the clergy did not decrease. Romero describes the shooting of his friend Jesuit Father Rutilio Grande as a key experience . As a result, he refused to attend official events. In particular, his absence from the inauguration of the Salvadoran President and President of the military party Carlos Humberto Romero was resented by the oligarchs. Instead of attending the inauguration ceremony, he read his second pastoral letter at the same time , where, among other things, he wrote an “awakening self-understanding of the people as a community of faith and life, which is called to accept their own history in a process of redemption that begins with theirs own liberation should begin ”stated. Rivera y Damas, then Bishop of Santiago de María , helped spread the word. This step contributed significantly to Romero's acceptance among the clergy.

On Labor Day , which fell on a Sunday in 1977, another demonstration was bloody broken up. On November 25, the government passed a “Law for the Protection and Maintenance of Public Order”, legalizing much of its reprisals. The law was severely condemned in the country and internationally. Towards the end of the year Romero was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize for his work for human rights and against impunity for evildoers . 118 British MPs were among the nearly 1,000 signatories. His supporters realized that such statements would strengthen his position and, if necessary, protect his life. In early 1978 he received an honorary doctorate from the US University of Georgetown .

Meanwhile, state repression increased steadily and increasingly concentrated on rural areas and the advocacy of campesinos . According to the archbishopric, there were around 1,063 political prisoners , 147 murders by the security forces and 23 " desaparecidos " by the end of 1978 . The OAS confirmed these numbers. In a homily dated April 30, 1978, Romero denounced the Supreme Court's negligence and negligence in prosecuting the crimes. The latter responded by asking the bishop to name “horse and rider”. Instead of naming names - for which he could have been legally prosecuted - he argued with the passivity of the judiciary in the face of state violence in recent years and placed it in a moral context of a human rights position . The Tribunal did not answer.

Increasing politicization

In mid-1978 the Church was preparing for the conference of bishops in Puebla, Mexico, which followed the conference in Medellín . The Salvadoran Conference elected Marco René Revelo as its delegate. In general, there was a general fear among the so-called liberation theologians (including Romero) that the positions reached in Medellín, that the church should be guided by the suffering and life of the people, would again be put up for discussion. Due to the death of John Paul I , who should have chaired the conference, it was postponed from October to January 1979 and opened by John Paul II . Romero used this time to write his third pastoral letter with Rivera. In it he looked in detail at the struggles for freedom of the peasant unions, the possibilities for the people to organize themselves into a liberation movement, and the question of how far the use of force against the military dictatorship could be justified. Other bishops had previously disapproved of the work of the left-wing peasant organizations. At the same time as the pastoral letter was published, Romero and Rivera distanced themselves from their work. The state media hyped this incident into a political division of the church.

The three main theses of the pastoral letter were:

- The church message is religious; but from their mandate result “mandate, light and strength to help the human community to build and consolidate according to divine law ”. It is the genuine mandate of the church to support the congregations and to build them up. Because the word of God contains concrete postulates, it should not only be spoken but also lived. In particular, this could result in political engagement.

- The church does not elect a political organization against another, but it uses the means given to it to "establish and strengthen human community according to divine law".

- The church is supposed to illuminate attempts of the organization towards liberation with a Christian hope for holistic liberation. “It has a truly spiritual dimension; its goal is salvation and bliss in God and calls for a conversion of heart and spirit. It is not satisfied with simply changing structures. It rules out violence because it considers it 'unchristian', 'unevangelical', ineffective and incompatible with the dignity of the people. "

In Puebla itself, Romero kept a low profile. Bishop Pedro Arnoldo Aparicio publicly attacked his reports on the crimes of the Salvadoran state, to which Romero did not respond. This and other incidents led - up to the Pope - to several attempts at arbitration, which were also successful after the intervention of Cardinal Sebastiano Baggio . Despite all previous skepticism, Romero assessed the results from Puebla as positive, but criticized the sometimes distorting reporting, which excluded the demand for a more equitable distribution of wealth.

While Romero was in Rome for the beatification of Francisco Coll in May 1979 , government forces arrested five leading members of the Bloque Popular Revolucionario (People's Revolutionary Bloc - BPR). In response, the organization occupied consulates from various embassies as well as Romero's cathedral . The violent attempt to disband the cathedral occupation, in which 20 people were shot, was filmed by international journalists and went around the world on May 8th. In his first sermon after his return to El Salvador, which he held near the Plaza de la Libertad because of the ongoing occupation , Romero showed solidarity with the BPR demands. The occupations lasted and expanded throughout the month of May. Many occupiers were violently assaulted. In total there were around two hundred dead and disappeared, and there were a comparable number in the following month.

Coup of October 15, 1979

A Junta Revolucionaria de Gobierno young officers seized power on October 15. The coup was planned well in advance. In the run-up to this, Romero's position was scrutinized from many sides, including by US diplomats. The junta appointed a handful of civilians who enjoyed Romero's trust to government offices. That was one of the main reasons why he accompanied the change critically, but primarily as a warning to be prudent and patient; an attitude that not all organizations followed. He lost credibility significantly when it became apparent that the junta would not be able to control the continued violence of the security forces. This crisis culminated on December 17th in a hostile occupation of the church buildings by the Ligas Populares 28 de Febrero (LP-28), founded on the occasion of the massacre of February 28 in the Plaza de la Libertad . At the same time, right-wing officers reasserted the power of the military . A movement led by Colonel José Guillermo García brought about a restructuring of the army, which practically amounted to a counter-coup before the junta cabinet was officially appointed . The civilian members tried to break García's position of power with an ultimatum to the High Court of Justice , but were unsuccessful and resigned after Romero's likewise unsuccessful attempt at mediation.

While the Christian Democrats subsequently tried to persuade qualified personalities to form a government, the three largest left movements (FAPU, BPR and LP-28) joined forces on January 11, 1980. Others followed. On January 22nd, a mass uprising broke out in the capital (the date was supposed to commemorate the victims of the peasant uprising in 1932), which was shot down by snipers. Romero left El Salvador to speak to the Pope in Rome on January 30th and then to accept an honorary doctorate from the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in Belgium on February 2nd .

Last days

Upon his return, Romero found the situation in El Salvador practically unchanged. As a new project he tried to prevent the USA from granting military aid again. To this end, he wrote a letter to this effect to President Jimmy Carter in agreement with his ward . The Vatican State Secretariat was very concerned about this process. On March 14, 1980, the new US Ambassador to El Salvador, Robert E. White , presented Romero with a positive response from Cyrus Vance , US Secretary of State ( Carter's cabinet ).

Romero's sermons have long been broadcast across the country and beyond. When right-wing extremist groups bombed the church radio station, this contributed to its spreading through other Latin American radio stations. In February 1980 Romero mentioned death threats against himself for the first time in his sermons, from which he had received serious threats since his appointment. Miguel d'Escoto Brockmann , then Nicaragua's Foreign Minister and also a priest, offered him asylum in his country, in which the Somoza dictatorship had just been successfully overthrown . Romero refused on the grounds that he could not leave his people alone and accepted the risk of the moment.

assassination

Course of events and perpetrators

Romero was shot by a sniper in front of the altar on March 24, 1980 after a sermon in the hospital chapel of the Divina Providencia (German: Divine Providence ). Major Roberto D'Aubuisson Arrieta , who trained in the US-run School of the Americas , was deputy chief of intelligence and mastermind behind the murder of Romero and the death squads in El Salvador.

The Comisión de la Verdad para El Salvador came to the following conclusion in a later investigation:

- Former Major Roberto D'Aubuisson Arrieta gave the order to assassinate the archbishop and gave precise instructions to members of his security staff, acting as a ' death squad ', to organize and oversee the conduct of the murder.

- The captains Álvaro Saravia and Eduardo Avila took an active part in the planning and execution of the assassination, as did Fernando Sagrera and Mario Molina.

- Amado Antonio Garay, driver of the former Captain Saravia, was assigned to drive the shooter to the chapel. Garay was an immediate witness when the shooter dropped a single .22 caliber high-speed bullet from a four-door red Volkswagen in an attempt to kill the archbishop.

- Walter Antonio "Musa" Alvarez was involved with Saravia in paying the "fee" for the assassin.

- The failed assassination attempt against the judge Atilio Ramírez Amaya was an action that was intended to counteract the clarification of the events.

- The Supreme Court took an active role in preventing Saravia's expulsion from the United States and subsequent arrest, adopting a stance of impunity in the planning and execution of the murder.

background

The political murders of the death squads were intended to prevent a possible revolution by eliminating the intellectual elite and capable leaders of the resistance (see “ Dirty War ”). Since the leaders of the resistance mostly came from the middle class, but the majority of them were campesinos, i.e. mostly landless peasants, its top should be broken. This tactic was suggested by US military advisors and planned for the Civil War. So were u. a. Dropped by helicopters from notes over San Salvador with the slogan "Be a patriot - kill a priest". Óscar Romero said in his last sermon on March 23, 1980:

“No soldier is forced to obey an order that violates the law of God. No one is subject to an amoral law. It is time you rediscovered your conscience and held it higher than the commands of sin. The Church, defender of divine rights and God's justice, of human dignity and of person, cannot remain silent in the face of these great atrocities. We urge the government to recognize the futility of reforms born of the blood of the people. In the name of God and in the name of this suffering people, whose complaints rise louder to heaven every day, I ask you, I ask you, I command you in the name of God: Stop the repression ! "

Political Consequences

The murder of Óscar Romero sparked a civil war in El Salvador that claimed more than 75,000 lives, including 70,000 civilians, over 12 years. Already at Romero's funeral, which was attended by around a million people, there was a massacre with 40 fatalities among the participants.

Some eyewitnesses disappeared without a trace , others, such as B. the investigating judge of the murder case, who fled to Nicaragua after attempting murder , were intimidated or fled abroad.

Work-up

At the beginning of the 1990s, the Comisión de la Verdad para El Salvador and the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights (organ of the OAS ) conducted independent investigations into the course of events and the background to the murder of Oscar Romero. They came to a similar conclusion. On March 20, 1993, five days after the report was published, the parliament in El Salvador issued an internationally highly controversial general amnesty for all crimes related to the civil war that were committed before 1992.

On September 23, 2004, Álvaro Saravia, head of D'Aubuisson's security staff and death squad commander, was found guilty in absentia in a civil trial in California as one of the masterminds of the murder of Romero by Judge Oliver Wanger. It was the first international time that anyone had been convicted in the Romero case.

Arrest warrant for murder suspects

On October 26, 2018, the arrest warrant was issued for the fugitive murder suspect Álvaro Rafael Saravia , who had been arrested in Miami in 1987 and extradited to El Salvador. In the previous year, the 1993 Amnesty Act was repealed and a retrial was ordered in the Romero murder case.

Honors

Religious honors

On March 24, 1994, the process of beatification according to Roman Catholic canon law began for Óscar Romero. The Episcopal Church in the USA tentatively added it to their Calendar of Saints for the period 2006–2009 . He has also been listed as a martyr for March 24th in the liturgical calendar of the Catholic Diocese of Old Catholics in Germany since the early 1990s . The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America still has it (2013) for March 24th on their calendar. In February 2008 the Vatican announced that in the process of beatification Romero had doubts about the motives for his murder, so that the process would take longer than planned. Curia Cardinal José Saraiva Martins , Prefect of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints , explained that the motive for the murder must be “hatred of the faith” (odium fidei) and not only political or social reasons. For elevation to martyrdom every aspect of the circumstances of the martyrdom must be clarified. In August 2014 Pope Francis declared that he had “unblocked” the process of canonization. On January 9, 2015, the Theological Council of the Vatican Congregation for Canonization recognized martyrdom. Pope Francis confirmed this on February 3, 2015. The beatification took place on May 23, 2015 in San Salvador. On October 14, 2018, Óscar Romero was canonized by Pope Francis.

On the west facade of Westminster Abbey , a statue of Romero was placed among the "martyrs of the 20th century". In the Basilica of San Bartolomeo all'Isola , the memorial of the martyrs of the 20th century maintained by the Community of Sant'Egidio , you will find Romero's missal. In 1980 Romero was awarded the Peace Prize of the Swiss Ecumenical Alliance for Action .

Maximilian Kolbe , Manche Masemola , Janani Luwum , Grand Duchess Elisabeth of Russia , Martin Luther King , Óscar Romero , Dietrich Bonhoeffer , Esther John , Lucian Tapiedi and Wang Zhiming .

Civil honors

Since 1970 he has been Ciudadano Ilustre (honorary citizen) of the municipality of Ciudad Barrios (1970) and since 2000 Hijo Meritísimo (esteemed son) of the Parliament of El Salvador.

The international airport of San Salvador was named in 2014 by Óscar Romero. In 2015 an asteroid was named after him: (13703) Romero .

Academic honors

- Georgetown University , USA (1978).

- Université catholique de Louvain , Belgium (1980, before his death).

- Universidad de El Salvador , El Salvador (1980, after his death).

- Universidad Centroamericana “José Simeón Cañas” (UCA), El Salvador.

Aftermath

From the 1980s to the present day, a number of institutions and initiatives have named themselves after Oscar Romero.

Oscar Romero houses

The institutions that have given themselves the name “Oscar Romero House” since 1980 or that have been newly founded as such, realize their commitment in different ways.

The Oscar-Romero-Haus (Bonn) is a self-managed dormitory for students and trainees founded by Martin Huthmann , which also houses various initiatives.

The Oscar Romero parish center in Gersthofen was built in 1998 and founded a support association in 2002, which maintains contact with the people in El Salvador and distributes donations. The Bishop Oscar Romero House in Hanover was a youth education center of the Hildesheim diocese ; it was closed in 2004.

The RomeroHaus Luzern was founded in 1986 by the Bethlehem Mission Immensee . As a conference center, it promotes solidarity between continents and cultures, between religions and churches, between politics and business, between women and men. The Hotel RomeroHaus has 13 guest rooms with a total of 34 beds. The Oscar Romero House in Oldenburg is connected as a dormitory to the Catholic University Community in Oldenburg and was rebuilt in 2003/2004.

The Oscar Romero House for single male homeless people, Viersen is aimed at people with particular social difficulties. It is sponsored by an association that works with the Caritas Association of the Aachen diocese .

The Oscar Romero house in Walsum , built in 1996, is the community center of the Catholic Church. Parish of St. Dionysius in Duisburg-Walsum.

It can be assumed that, besides Germany and Switzerland, there are even more Oscar Romero houses in other countries (see e.g. the Romero House in Toronto ) and especially in Latin America.

Initiatives

The Christian Initiative Romero (CIR), founded in 1981, is a registered, non-profit association with headquarters in Münster and further offices in Berlin and Nuremberg . The donation volume averages 500,000 euros per year. The focus of the work is the support of around 90 grassroots movements and organizations mainly in Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras as well as campaign and educational work in Germany. It is about respect for human rights, the strengthening of civil society, the self-determination of women, the rights of the indigenous population, decent working conditions and sustainable agriculture. Examples of the campaigns supported and partly initiated by the CIR are the Campaign for Clean Clothes (CCC), the Corporate Accountability - Network for Corporate Responsibility, the Campaign "Women Votes Against Violence" and the ProNATs (Pro los Niños y Adolecentes Trabajadores - For the working children and young people).

The Catholic Men's Movement in Austria (KMBÖ) has been awarding a € 10,000 Romero Prize since 1980 . In addition, there is the “ Oscar Romero Prize ” in Germany , which has been awarded by the Friends of the Oscar Romero House in Bonn since 2003 and is endowed with € 1,000. By awarding these prizes, the socio-political and social commitment of the respective award winner is recognized and strengthened.

In March 2010, on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the murder of Oscar Romero, there were numerous cities in Germany, Austria and Switzerland (including Bayreuth , Berlin, Bonn, Frankfurt am Main , Hamburg , Innsbruck , Koblenz , Königswinter , Lucerne, Papenburg , St. Pölten ) Events on Romero's topicality, the theology of liberation and the political situation in Latin America.

Movies

- Oscar Romero - Death of an Archbishop. Documentary by Rena and Thomas Güfer, 2003.

- The Franco-German feature film SAS Malko - Commissioned by Raoul Coutard for the Pentagon begins with the assassination of Romero. In the German version, the film takes place in the fictional country of Santo Domingo .

- In the film Salvador by Oliver Stone , the director portrayed El Salvador, which was torn by civil war. The film is largely based on real events and deals, among other things, with the events surrounding the murder of Romero. Stone vehemently attacked the US policy on Central America. In the absence of US funding, the film was financed with English capital.

- 1986: Recording and broadcast of the Berliner Compagnie's play Oscar Romero by WDR. It was performed over 300 times in theaters and churches in German-speaking countries.

- The film Romero by John Duigan with Raúl Juliá in the leading role created an artistic monument for the bishop in 1989.

- El Salvador - The archbishop is subversive . A historical documentary by the Swiss journalists Otto C. Honegger and Oswald Iten. They accompanied Archbishop Romero in 1979 and describe his commitment to peace and justice. Five months after the film was broadcast, Romero was murdered.

Works

- Don't be silent. From the stooge of power to the advocate of the poor . Texts in German first edition. Edited by Jesús Delgado. Camino, Stuttgart 2015, ISBN 978-3-460-50000-6 .

Audio book

- Oscar Romero - "But there is a voice that is strength and breath ..." An audio book by Peter Bürger, Onomato-Verlag 2018, total playing time 78 min., ISBN 978-3-944891-67-5 .

literature

- Berne Ayalá: La Bitácora de Caín. Letras Prohibidas, San Salvador 2006.

- Brigitte Becker (ed.): Oscar Arnulfo Romero: Martyrs for the People of God (Preface: Norbert Greinacher, translated from Spanish and English by Brigitte Becker). In: Representatives of Liberation Theology. Walter , Olten / Freiburg im Breisgau 1986, ISBN 3-530-70301-X .

- James R. Brockman: Óscar Romero. A biography. (Translated from the American original Romero by Maria-Antonia Fonseca-Visscher van Gaasbeek) Paulus, Freiburg (Switzerland) 1990, ISBN 3-7228-0240-7 .

- Peter Bürger : Oscar Romero, the synodal church and abysses of clericalism. On the 40th anniversary of the death of the witness from El Salvador. BoD, Norderstedt 2020. ISBN 978-3-7504-9377-3

- Wolfgang Max Burggraf: San Romero de America. In: Festschrift “Where spinners tie colorful nets”. Friends of the Óscar-Romero-Haus, Bonn 1999, ISBN 3-924958-21-1 .

- Markus Ebenhoch: The theologumenon of the “crucified people” as a challenge for contemporary soteriology. In: Religion, Culture, Law. Volume 10, Lang, Frankfurt am Main / Berlin / Bern / Brussels / New York, NY / Oxford / Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-631-55995-6 .

- Horst Gust: Óscar Arnulfo Romero. Advocate of the Poor (biography). In: Christian in the world. Issue 49, Union, Berlin 1980.

- Klaus Hagedorn (Ed.): Óscar Romero: integrated between death and life. 15 years Óscar Romero Foundation in Oldenburg; Texts and documents on Óscar Romero and on the Room of Silence in the Óscar Romero House in Oldenburg. BIS-Verl. the Carl-von-Ossietzky-Univ., Oldenburg 2006, ISBN 978-3-8142-2039-0 .

- María López Vigil: Óscar Romero: a portrait of a thousand pictures (Translator: Michael Lauble). Exodus, Luzern 1999, ISBN 3-905577-35-6 .

- Martin Maier : Óscar Romero: Master of Spirituality. Herder, Freiburg 2001, ISBN 3-451-05072-2 .

- Martin Maier: Óscar Romero. Fighters for Faith and Justice (preface by Jon Sobrino). In: Herder spectrum. Volume 6201, revised and expanded new edition, Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau / Basel 2010, ISBN 978-3-451-06201-8 .

- Martin Maier: Óscar Romero: mística y lucha por la justicia ( transl .: Malena Barro). Herder, Barcelona 2005, ISBN 84-254-2389-9 .

- Johannes Meier : Oscar Arnulfo Romero. The necessary revolution. With a contribution by Jon Sobrino about the martyr of liberation. Forum Political Theology 5.

- Diethelm Meißner: The "Church of the Poor" in El Salvador: a church movement between people's and liberation organizations and the constituted church. (Representation of the historical connections in the period from 1962 to 1992 and the political, social and ecclesiological problems in their environment.) Mission and Ecumenism, Erlangen 2004, ISBN 3-87214-350-6 .

- Roberto Morozzo della Rocca: Primero Dios: Vita di Óscar Romero. Mondadori, Milan 2005.

- Ulrich Nersinger: Assassination attempt on faith, The martyrdom of Óscar A. Romero , Bernardus Verlag Aachen 2015, ISBN 978-3-8107-0232-6

- Jon Sobrino : The Price of Justice. Letters to a murdered friend ( translated from the original Spanish Cartas a Ellacuría by Gerhart Eskuche). In: Ignatian impulses. Volume 25, Echter, Würzburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-429-02945-6 .

- Emil Stehle (Ed.): In my distress. Diary of a martyr bishop. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1993, ISBN 3-451-23095-X .

- Daniel Heinz: Romero y Galdámez, Oscar Arnulfo. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 8, Bautz, Herzberg 1994, ISBN 3-88309-053-0 , Sp. 637-640.

- Michael Sievernich SJ: San Romero de América . Editorial, Voices of the Times, Issue 3, 2015

- Christian Weisner, Friedhelm Meyer, Peter Bürger (eds.): Commemorates the canonization of Oscar Romero by the poor. BoD, Norderstedt 2018, ISBN 978-3-7460-7979-0

Web links

- Literature by and about Óscar Romero in the catalog of the German National Library

- Romero's tomb in the Cathedral of San Salvador

- Beatification website

- Ecumenical call for May 1, 2011: “Commemorate the canonization of the martyr San Oscar Romero”

- Óscar Romero in the television documentary "Political Murders" on 3sat

- Óscar Romero - a sign of contradiction

- Dossier on Oscar Romero in Latin America

- Audio sample for the audio book "Oscar Romero"

- Oscar Romero and the Church of the Poor. On the 40th anniversary of the death of the witness from El Salvador. Free digital special volume of edition pace 2020. With contributions and a. by Norbert Arntz, Peter Bürger, Christian Initiative Romero (CIR), Andreas Hugentobler, Willi Knecht, Martin Maier SJ, Stefan Silber and Paul Gerhard Schoenborn. Download option here

- Óscar Romero in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints

- Entry on Óscar Romero on catholic-hierarchy.org

Notes and wording

- ↑ The Vatican previously tried to stop the honor, probably to avoid diplomatic tensions, or at the urging of the envoy of the Salvadoran government. As a result, he was offered an honor from Loyola University Chicago , which he turned down. He suspected US diplomats of having initiated the honor to arrange a meeting to negotiate with General Carlos Humberto Romero , who was supposed to be in town at the same time.

- ↑ Unión de Trabajadores del Campo (UTC), Federación Cristiana de Campesinos Salvadoreños (FECCAS), Frente de Agricultores de la Región Oriental (FARO). UTC and FECCAS merged in 1975 to form FECCAS-UTC.

- ↑ Article 42 of the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World of the Second Vatican Council has the same wording.

- ↑ In November 1979, the USA supplied the country with gas masks and bulletproof vests valued at approximately US $ 200,000.

-

↑ Original document at the United Nations ( Memento of September 20, 2008 in the Internet Archive ), pp. 132-138 (PDF; 2.96 MB)

El 24 de marzo de 1980 el Arzobispo de San Salvador, Monseñor Oscar Arnulfo Romero y Galdámez, fue asesinado cuando oficiaba la misa en la Capilla del Hospital de la Divina Providencia.

La Comisión concluye lo siguiente:- El ex-Mayor Roberto D'Aubuisson Arrieta dio la orden de asesinar al Arzobispo y dio instrucciones precisas a miembros de su entorno de seguridad, actuando como «escuadrón de la muerte», de organizar y supervisar la ejecución del asesinato.

- Los capitanes Alvaro Saravia y Eduardo Avila tuvieron una participación activa en la planificación y conducta del asesinato, así como Fernando Sagrera y Mario Molina.

- Amado Antonio Garay, motorista del ex-Capitán Saravia, for asignado para transportar al tirador a la Capilla. El señor Garay fue testigo de excepción cuando, desde un Volkswagen rojo de cuatro puertas, el tirador disparó una sola bala caliber .22 de alta velocidad para matar al Arzobispo.

- Walter Antonio “Musa” Alvarez, junto con el ex-Capitán Saravia, tuvo que ver con la cancelación de los “honorarios” del author material del asesinato.

- El fallido intento de asesinato contra el Juez Atilio Ramírez Amaya fue una acción deliberada para desestimular el esclarecimiento de los hechos.

- La Corte Suprema asumió un rol activo que resultó en impedir la extradición desde los Estados Unidos, y el posterior encarcelamiento en El Salvador del ex-Capitán Saravia. Con ello se asignaba, entre otras cosas, la impunidad respecto de la autoría intelectual del asesinato.

-

↑ (Text in italics not translated): Yo quisiera hacer un llamamiento, de manera especial, a los hombres del ejército. Y en concrete, a las bases de la Guardia Nacional, de la policía, de los cuarteles. […] Hermanos, but de nuestro mismo pueblo. Matan a sus mismos hermanos campesinos. Y ante una orden de matar que dé un hombre, debe prevalecer la ley de Dios que dice: «No matar». Ningún soldado está obligado a obedecer una order against la Ley de Dios. Una ley inmoral, nadie tiene que cumplirla. Ya es tiempo de que recuperen su conciencia, y que obedezcan antes a su conciencia que a la orden del pecado. La Iglesia, defensora de los derechos de Dios, de la Ley de Dios, de la dignidad humana, de la persona, no puede quedarse callada ante tanta abominación. Queremos que el gobierno tome en serio que de nada sirven las reformas si van teñidas con tanta sangre. En nombre de Dios y en nombre de este sufrido pueblo, cuyos lamentos suben hasta el cielo cada día más tumultuosos, les suplico, les ruego, les ordeno en nombre de Dios: Cese lareprión.

Original speech on Youtube (excerpt).

Individual evidence

- ↑ badische-zeitung.de , comments , May 22, 2015, Gerhard Kiefer: Murdered in the fight against poverty and exploitation (May 25, 2015)

- ^ A b Solemn ceremony in San Salvador: Óscar Romero beatified - tagesschau.de. In: tagesschau.de. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015 ; accessed on May 23, 2015 .

- ^ Documents of the II. And III. General assembly of the Latin American episcopate in Medellín and Puebla : Secretariat of the German Bishops' Conference , Bonn 1968/1979.

- ↑ Estudios Centroamericanos (ECA): Comunicados del Arzobispo de San Salvador a raíz de la muerte de Padre Rutilio Grande (1977). 341, 254-257.

- ^ Estudios Centroamericanos (ECA): Reporte de la Comisión internacional de Juristas sobre la “Ley de defensa y garantía del orden público” (1978). 359, 779-786.

- ^ Secretaría de Comunicación Social del Arzobispado de San Salvador: Informe sobre lareprión en El salvador (December 12, 1979). Boletín informativo 10.

- ↑ Estudios Centroamericanos (ECA): La OEA y los derechos humanos en El Salvador (1979). 363-364, 53-54.

- ^ Estudios Centroamericanos (ECA): Las Homilías del Monseñor Romero y el Poder judicial en El Salvador (1978). 355, 330-332.

- ^ Text published in Estudios Centroamericanos (ECA): Monseñor Óscar A. Romero: Su Pensamiento. Vol. IV., Pp. 243-248; and in: La Voz de los sin Voz. Pp. 405-410; there is a recording of the sermon.

-

↑ Documentation ( Memento of the original from February 17, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on the canonical process website (requires Adobe Flash ).

An English translation of the four pastoral letters is available in Voice of the Voiceless: The Four Pastoral Letters and Other Statements (1985). Orbis Books, ISBN 978-0-88344-525-9 .

- ↑ James R. Brockman: Oscar Romero: A Biography. Freiburg Switzerland 1990, ISBN 978-3-7228-0240-4 , p. 188 f .

- ↑ letter D'Escoto of 15 February and letter Romeros February 27 1980th

- ↑ De la Locura a la Esperanza: la guerra de los Doce Años en El Salvador (extract) - Report of the Comisión de la Verdad para El Salvador

- ↑ Tomás Calvo Buezas: El gigante dormido: El poder Hispano en los Estados Unidos. Los Libros de la Catarata, 2006, ISBN 978-84-8319-284-9 , p. 54.

- ↑ No prosecution for Jesuit murderers. Despite an Interpol arrest warrant, El Salvador refuses to extradite soldiers wanted by the Spanish judiciary. In: The Standard . September 13, 2011.

- ↑ Óscar Romero's last sermon on March 23, 1980, Cathedral of San Salvador , original speech on Youtube (excerpt)

- ↑ Consideraciones sobre la Comisión de la Verdad ( en ) in the annual report on the human rights situation in El Salvador.

- ^ Entry in the American encyclopedia Judgepadia ( Memento of October 5, 2009 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Documents ( memento of July 11, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) on the case at the Center for Justice and Accountability .

- ↑ Did he shoot Romero? Arrest warrant for murder suspects. kath.net from October 26, 2018

- ^ Episcopal Church: Saints added to calendar . 75th General Convention, March 13-21 June 2006.

- ↑ Saints, veneration of saints. ( Memento from January 27, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) In: Alt-Katholisch. Catholic diocese of the old Catholics in Germany.

- ↑ The belated canonization of Óscar Romero. In: NZZ , October 13, 2018, title of the print edition

- ^ Martyrdom recognized by Archbishop Oscar Romero. ( Memento from January 9, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) In: kathisch.de .

- ^ Promulgazione di Decreti della Congregazione delle Cause dei Santi. In: Daily Bulletin. Holy See Press Office , February 3, 2015, accessed February 3, 2015 (Italian).

- ^ Michael Sievernich SJ: San Romero de América. Editorial, Voices of the Times, Issue 3, 2015

- ↑ October 14, 2018

- ^ Memories kept in the Basilica. ( Memento of January 21, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) In: Website of the Basilica di San Bartolomeo all'Isola.

- ↑ Aeropuerto Internacional será como nombrado "Monseñor Óscar Arnulfo Romero." In: elsalvador.com (El Diario de Hoy). January 16, 2014.

- ↑ Where spinners tie colorful nets - 25 years of the Oscar-Romero-Haus Bonn . Friends of the Oscar-Romero-Haus e. V. (Ed.), Information Center Latin America (ila), Bonn 1998

- ↑ pg-gersthofen.de

- ↑ Diocese of Hildesheim: New Structures for a Changed World (October 15, 2003)

- ↑ comundo.org ( Memento from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ comundo.org ( Memento from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ oscar-romero-haus-oldenburg.de

- ↑ psychosoziales-adressbuch-kreisviersen.de

- ↑ www.dionysius-walsum.de

- ↑ romerohouse.org

- ↑ ci-romero.de ( Memento from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ ci-romero.de

- ↑ romerohausbonn.wordpress.com

- ^ Josef Senft: The challenge of liberation . Report on the Bonn Oscar Romero Days from March 14 to 24, 2010.

- ↑ Political Murders (6). Oscar Romero - Death of an Archbishop. In: 3sat.de. October 7, 2004.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Luis Chavez y Gonzalez |

Archbishop of San Salvador 1977–1980 |

Arturo Rivera y Damas |

| Francisco José Castro y Ramírez |

Bishop of Santiago de María 1974–1977 |

Arturo Rivera y Damas |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Romero, Óscar |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Romero y Galdámez, Óscar Arnulfo |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Salvadoran Roman Catholic bishop, saint |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 15, 1917 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Ciudad Barrios |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 24, 1980 |

| Place of death | San Salvador |