Death marches by concentration camp prisoners

The death marches of concentration camp prisoners (sometimes euphemistically called evacuation marches ) are various "evacuation operations" carried out by the SS guards in the final phase of the Second World War . From 1944 the SS dissolved concentration camps close to the front , including z. B. the notorious extermination camp Auschwitz-Birkenau , and forced most of the concentration camp prisoners to march towards the center of the Reich or locked them as passengers in railroad cars for removal . Prisoners who were unable to march were very often shot in large numbers. Many parts of the camp were set on fire by the SS .

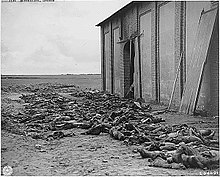

Numerous concentration camp prisoners did not survive the days and weeks of marches or transports: They froze to death, starved or collapsed weakly and were then shot by the SS guards. Individual trains came by chance under attack by the used ground combat fighter pilot of the Allied troops, others remained unserved on alternative routes lie; some death marches ended in a catastrophe like in connection with the sinking of the Cap Arcona or in a massacre like the Isenschnibber field barn in Gardelegen .

term

The term “ death march ” was coined by victims in retrospect and has become a common term in scientific literature. The standard work Encyclopedia of National Socialism defines the death march as a “phenomenon in the Third Reich, especially towards the end of the war, when the prisoners of several concentration camps were evacuated, i. H. were forced in large numbers to march over long distances under unbearable conditions and brutal mistreatment, with a large number of them being murdered by the escort teams. "

On some marches, the survivors were transported on by train. Sometimes the prisoners were picked up by lorries when the camps were cleared or they were immediately put in railroad cars. These transports, which also lasted for days, took place under adverse circumstances and claimed numerous lives, are often referred to as death marches.

The term "evacuation" is often used in connection with the liquidation of the concentration camps. However, this term commonly refers to a rescue operation where people are temporarily moved to a safe place in the face of impending danger. In the case of the "evacuations" mentioned here, the SS prevented the Allied troops from being liberated and caused further deaths with the relentless evacuation. Therefore the terms “evacuation” or “dissolution” of the camps seem more appropriate. The historian Katrin Greiser points out that 'evacuation' is not the language of the perpetrators, but is in use in survivors' texts and is widespread through the German translation of the Nuremberg Trials Protocols (evacuation). Former SS members had spoken of ' evacuation ', 'repatriation', 'relocating', 'sending on transport' or 'rescuing people'.

During most of the death marches, numerous exhausted prisoners were shot by the guards along the way. It was these arbitrary killings in particular that led to the term death march. Diana Gring defines "death march crimes" as "non-stationary Nazi acts of violence in the end of the war that were in connection with the evictions of the concentration camps and that were committed during the marches or at the corresponding stopover points and endpoints of the route." The crimes during this period overall are referred to as end- stage crimes (1944/1945) .

Systematic comparative analyzes are only just beginning. Diana Gring points out the following important common features of the death marches: randomness of the crime scene, heterogeneity of groups of perpetrators and separation of the upper and lower levels of command. Katrin Greiser has worked out that the death marches and transports are to be seen as a continuation of the concentration camp system. Its basic structures continued to function in its last phase and, as has been the case several times since 1933, adapted flexibly.

Chronological order

The forced withdrawal of the German troops from the summer of 1944 onwards led to the concentration camps that had come close to the front, with their numerous satellite camps, being dissolved and evacuated. With the evacuation of the Auschwitz camps in January 1945, the prisoners' death marches began . When the Red Army or the Western Allied troops approached , the prisoners were "evacuated" in marching columns or taken away by train - often in open freight cars. Most recently, in mid-April 1945, the SS forced more than 10,000 prisoners to march from Neuengamme concentration camp .

There are three phases in the evacuation of concentration camps:

In a first phase between August 1944 and mid-January 1945, the camps were largely closed in an orderly manner. Most of the prisoners from the satellite camps were concentrated in the main camp and some were removed weeks before the camp was closed.

This was followed by a period of time until the beginning of April 1945 in which evacuations were increasingly hectic and hardly prepared. Before leaving , the SS guards often murdered the prisoners who were “unable to march”, as well as many mostly German political prisoners who were believed to be able to resist.

In the last phase there were hasty and chaotic marches for which there were hardly any alternative camps as destinations.

Controversial interpretations

The decision-making process for evacuating the camps can not be reconstructed because of the incomplete sources . It is highly doubtful whether a “Führer order” for the “extermination of all prisoners and guards”, which is mentioned in Felix Kersten's memoir , was actually given; Also, allegedly locally issued corresponding extermination orders, which are reported on almost every concentration camp, cannot be substantiated and were not carried out in any concentration camp.

It is possible that Heinrich Himmler issued an order on June 17, 1944 not to simply let the concentration camp inmates fall into the hands of the Allied liberators. The higher SS and police leaders were given the authority to order an " evacuation " in the event of an imminent attack .

Apparently those responsible were following “a policy full of contradictions”. Himmler's “Jewish policy” was changeable and inconsistent in the last months of the war. Himmler himself tried to establish contacts with the Western Allies and therefore held Jewish prisoners hostage for a long time. In March 1945 he sent Oswald Pohl to various camps with the unequivocal task of curbing the mass deaths and, in particular, of sparing remaining Jewish prisoners. On April 15, 1945, a courier reached the leader of an "evacuation march" from Helmbrechts and conveyed Himmler's express order not to kill the Jews. On the other hand, on April 18, 1945 - April 14 is often wrongly mentioned - Himmler issued an order to the Flossenbürg concentration camp , which has not been handed down in the original , under no circumstances to leave the prisoners alive to the US army , since the liberated prisoners in Buchenwald " "behaved horribly towards the civilian population" and posed a danger to the civilian population.

The Hamburg Gauleiter Karl Kaufmann is credited with having concentration camp prisoners removed from the city because he feared that the victorious powers would have ordered severe immediate punishment at the sight of half-starved prisoners. As a “factual event”, the historian Karin Orth pointed out that the SS wanted to keep the concentration camp prisoners in their power until the end: “For whatever purpose - as work slaves who were supposed to build an impregnable fortress for the 'final battle', as a victim of an [...] apocalyptic downfall, as hostages for any negotiations with the Western powers or as a disposition for the expected anti-communist new beginning. "

For Daniel Goldhagen , the death marches represent the conscious continuation of the Holocaust by other means and a well-planned strategy for the annihilation of the Jewish people. Other historians point out that the majority of the evacuees were non-Jewish prisoners and lead the numerous victims to the complete chaos of the last months of the war and the collapse of supplies. The historian Eberhard Kolb comes to the conclusion: Not central orders, but "lower SS charges decided the fate of thousands of prisoners on the death marches." Karin Orth points out the main motives for the unbridled murderous activities of the escort team: "They killed, to speed up their own escape - and because the life of the concentration camp inmates was of no value to them. "

Victim

In many places, especially in East Germany , places where people died on death marches are marked with memorial stones on the streets . These memorials - mostly erected in the immediate post-war period - give no indication of which people were involved.

There are only widely differing estimates of the number of people who died on these death marches. Of the 714,000 concentration camp prisoners registered in December 1944, at least a third probably died by May 1945: through exhausting forced labor, through hunger, cold and exhaustion during the death marches, as well as through targeted killings that were not limited to those who remained weak on foot, through epidemics and malnutrition in overcrowded reception centers or as victims of fighting.

Unless they had been buried immediately, the victims were buried on the orders of the victorious powers after their arrival in cemeteries in the surrounding areas. These mostly anonymous graves often bear plaques or crosses with the inscription "Victim of National Socialism". Usually there is no indication of the reason for death or the exact place of death.

Individual marches

- On April 10, 1945 from Börgermoor and Esterwegen concentration camps . Around 1,100 prisoners had to march to Collinghorst , the survivors reached the Emsland camp Aschendorfermoor on April 11, 1945

- From Celle to Bergen-Belsen , so-called Celle hare hunt

- On April 23, 1945, the Colosseum subcamp in Regensburg with around 400 people was closed. It is estimated that around 50 people survived. They were liberated on May 2nd in Laufen (Salzach) .

- From the Hanover-Stöcken concentration camp to Mieste , from there in several groups to Gardelegen for the massacre in the Isenschnibber field barn

- From Heimkehle

- From Hannover-Ahlem to Bergen-Belsen

- In January 1945, approximately 1,000 women from the satellite camp Grünberg of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp and another 3,000 from other camps, divided into two groups of 2,000 people, first to the camp Christianstadt ( Krzystkowice ) driven. After a three-day stay, they had to continue marching. The route led via Dresden , Freiberg , Chemnitz , Zwickau , Reichenbach , Plauen to a camp in Helmbrechts , Bavaria, where they arrived on March 20, 1945 after almost 500 kilometers. From here they had to march to Volary (see Marsch Helmbrechts)

- From the Helmbrechts satellite camp (over 1,000 women from the Flossenbürg concentration camp ) to occupied Wallern (Volary) (see Langer Gang memorial ; approx. 200 km, from April 13 to May 4, 1945; via Schwarzenbach , Franzensbad , Marienbad )

- From Lieberose concentration camp (near Cottbus, February 1945)

- Massacre in Lüneburg during the evacuation of a satellite camp from Wilhelmshaven to Bergen-Belsen on April 11, 1945 (see memorial in the zoo )

- From the Wöbbelin concentration camp , early May 1945

- From the Schwarzheide subcamp to Theresienstadt, April 18 to May 8, 1945

From Buchenwald concentration camp

- Rail transport and death marches from the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp via Mieste and Letzlingen , ending in the Isenschnibber field barn near Gardelegen. 1,016 concentration camp prisoners, including at least 63 Jews, were murdered. 24 hours before the liberation by the US Army, the prisoners were penned into a stone barn at the end of the death march, where they were killed by fire and hand grenades and the barn set on fire.

- Various subcamps of the Buchenwald concentration camp via Roßleben , Nebra

- From the Leipzig-Abtnaundorf subcamp to Wurzen

- From Buchenwald external command Berga / Elster via Teichwolframsdorf , Gottesgrün , Neumark, Hauptmannsgrün, Irfersgrün, Stangengrün, Obercrinitz, Bärenwalde, Bockau , Sosa , Fällbach (April 18/19, 1945, 7 prisoners shot while escaping), Breitenbrunn / Erzgeb. , Rittersgrün , Gottesgab , Schmiedeberg to Theresienstadt and Manetin near Pilsen

- On April 5, the Buchenwald external command Berga / Elster a. American prisoners of war were driven via Greiz, Mühltroff, Dobareuth, Zedtwitz, Trogen, Rehau, Schirnding, Waldsassen (Kondrau) to the vicinity of Cham, where they reached the American front on April 19.

- From the Neustaßfurt satellite camp , u. a. via Lommatzsch , Wilsdruff , Kurort Hartha , Grillenburg , Klingenberg and Naundorf , to Annaberg-Buchholz (including memorials at the cemeteries in Tharandt and Naundorf)

- From the Markkleeberg subcamp , u. a. via Meißen , Niederau , Dresden , Freital , Tharandt , Höckendorf and Dippoldiswalde , to the Theresienstadt concentration camp (including a memorial at the Tharandt cemetery)

- From the Sonneberg concentration camp external command on April 4, 1945 with 467 concentration camp prisoners on two routes. The larger of them led over the Sonneberg upper town, to the Schusterhieb in Steinach , then over the Rennsteig through Gera area to Bohemian or Czech territory. The rest of the train lost its way on May 7th in Praseles, 50 km from Prague , after the SS men had fled the nearby Red Army . The second route probably led via Friedrichsthal to Bad Elster . 111 prisoners are said to have been liberated there by the Americans.

To the Baltic Sea

- From Königsberg at the end of January 1945 to Palmnicken - The death march ended on January 31 with a massacre of the remaining 3,000 predominantly female prisoners on the Baltic Sea. Only 15 people survived the mass murder .

- Death march Bremen-Blumenthal - Farge - Sandbostel and further: from Neuengamme concentration camp to ships on the Baltic Sea. The death march began on April 9, 1945 with 2,500 to 3,000 prisoners in Farge ; The goal was the Neuengamme main camp. Over 300 dead were buried in Brillit / Rotenburg district alone . Around 10,000 prisoners marched from Neuengamme to the Bay of Lübeck , where the survivors were loaded onto Cap Arcona , Thielbek and Athens . The ships were accidentally shot at by British bombers. 6,400 of the prisoners were killed.

- The Fürstengrube concentration camp death march of 1,283 prisoners, which began with a shooting action against 250 people, initially led to Ahrensbök in Schleswig-Holstein , the home of the camp manager. The surviving 400 prisoners were brought to the Cap Arcona , which was sunk by Allied aircraft on May 3, 1945 in the Bay of Lübeck.

- Of Sachsenhausen and Ravensbrück concentration camp after Raben Steinfeld south of Schwerin 16,000 people were sent. 200 memorial plaques have been placed along the main routes since 1976. In 1975 the death march memorial in the Belower Forest was opened in the city forest of Wittstock / Dosse , where thousands of prisoners had camped and probably hundreds of dead are buried .

- From Barth concentration camp

- From the concentration camp Fuhlsbüttel April 14 prisoners, hereunder prisoners were from the Riga ghetto , driven to Kiel, where on April 17, in work education camp Nordmark in keel Hassee arrived.

To and from Dachau concentration camp, Munich

- The Hessental death march from the Hessental concentration camp (municipality of Schwäbisch Hall , Württemberg ) to the Allach subcamp of the Dachau concentration camp , April 5–14. April 1945, probably 150–200 dead.

- From the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp to Dachau : Here, historical research, which is only rudimentary, assumes around 15,000 prisoners who were driven south in five large groups. The later GDR economics minister Fritz Selbmann describes in his book The Long Night the death march from Flossenbürg, on which he was able to escape. Camp commandant Max Koegel had arranged the march . After the war ended, over 5,000 dead were discovered along the routes. → Main article Flossenbürg concentration camp

- From Neckarelz concentration camp (North Baden) via Waldenburg to Dachau.

- From Buchenwald concentration camp via Flossenbürg to Dachau:

- According to the evidence available, this march started on April 4, 1945 in the Buchenwald concentration camp. It is said to have included around 1,500 prisoners at the beginning and to have reached Upper Bavaria via Flossenbürg , where it arrived in Kraiburg in two columns on April 29 and May 1, 1945 .

- It was found that a column of concentration camp prisoners marched through Kraiburg on April 29 or 30, and another probably on May 1, 1945. The first column marched from Kraiburg via Ensdorf, Oberneukirchen with the aim of getting to Austria via Laufen , while the second moved from Kraiburg towards Wasserburg . On their way, prisoners who were unable to march were continuously shot by the SS guards. The corpses were left lying next to the street or only superficially covered with earth.

- From the Obertraubling subcamp (to Flossenbürg) to Dachau beginning on April 16. Possibly. 100 survivors.

- From April 22nd, several death marches took place from the Dachau concentration camp . The prisoners were supposed to march into the Tyrolean Ötztal (see Alpine fortress ) in order to serve the regime as a bargaining chip if necessary. Individual marches reached the Tegernsee . Among other things, there were victims at the Landsberg satellite camps , the number of which is controversial.

Austria

- From Auschwitz to Loslau and on to Mauthausen : Peter van Pels , one of the people in hiding with Anne Frank , was sent on a death march from Auschwitz to Mauthausen on January 16, 1945, where he died three days before the liberation on May 5, 1945.

- From the Burgenland border to Mauthausen : In the last months of the war, thousands of Hungarian Jews who were involved in the construction of the so-called Southeast Wall were driven on death marches through Styria to the Mauthausen concentration camp . In the Oberwart district alone , hundreds of Jewish forced laborers were shot in the Rechnitz massacre and the Deutsch Schützen massacre in March 1945 . In April 1945 members of the Eisenerzer Volkssturm fired into the ranks of the starved people on the Präbichl . This massacre claimed around 200 deaths, but the number of people killed or murdered on the marches is much higher. In 1946, 12 men were sentenced to death in three trials by British military courts for these crimes . Since June 2004 a memorial on the Präbichl has been commemorating the victims of the massacre.

Serbia and Hungary

In September 1944 , the forced labor camp in Bor began to be dissolved. On September 17, 1944, a column of around 3,600 prisoners with around 100 Hungarian guards left the camp. The guards consisted mainly of camp inmates and the Hungarian military. From Bor the prisoners were led to a pontoon bridge at Smederovo and then on to Novi Sad , Sombor , Mohács and Szentkirályszabadja ( Balaton ). From there they were deported to the Flossenbürg , Sachsenhausen and Oranienburg concentration camps . During the forced march there were several attacks by partisans on the guards. This enabled some prisoners to flee to the partisans during the attacks and find life-saving protection. According to statements from surviving eyewitnesses, the Hungarian commanding officer in charge decided to bypass villages after crossing the Danube, some of which had to be covered at night. During the entire route, the majority of the prisoners were given food from the Serbian population at every possible opportunity. On September 19, 1944, a column of around 2500 prisoners with Hungarian guards left the camp under the command of units from SS Police Mountain Infantry Regiment No. 18 . The prisoners were driven to Belgrade, then on to Pančevo , Perlez , Titel , Crvenka and Szentkirályszabadja (Balaton). From Pančevo to Titel, the column was placed under the command of a guard team from the paramilitary squadron of the German team of the national minority leadership. In Titel, the Hungarian guards were again placed under the command of the Hungarian military. When they arrived in Szentkirályszabadja, part of the column had to march back to southern Baja , where they were then deported to the Flossenbürg and Buchenwald concentration camps. Another part was driven west to build the south-east wall . A large number of prisoners were mistreated and shot during the death marches. Surviving witnesses were u. a. Gyula Trebitsch and László Lindner . Miklós Radnóti described the forced march to build the south-east wall in a poem:

Crazy, he who falls down then gets up,

walks on

as walking pain moves feet and knees

and still walks as if wings carry him,

and in vain the ditch calls, he does not dare to stay.

See also

literature

- Cord Arendes , Edgar Wolfrum , Jörg Zedler (eds.): Terror to the inside. Crimes at the end of the Second World War. (= Dachau Symposia on Contemporary History. Volume 6). Wallstein, Göttingen 2006, ISBN 978-3-8353-0046-0 .

- Ulrich Sander : Murderous finale. Nazi crimes at the end of the war (edited by the International Romberg Park Committee ). Papyrossa Verlag, Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-89438-388-6 .

- Daniel Blatman: The Death Marches 1944/45. The last chapter of the National Socialist mass murder. From the Hebrew by Markus Lemke . Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-498-02127-6 ; Review: Wolfram Wette : Destruction on your own doorstep. In: Badische Zeitung , July 23, 2011

- Thomas Buergenthal : A child of fortune: How a little boy survived two ghettos, Auschwitz and the death march and found a second life. or … a new life…. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-10-009652-4 (Licensed edition of the Büchergilde, Frankfurt; reviews from shoa.de Wilfried Weinke: Day by Day . In: Die Zeit , No. 13/2006, p. 45. Soraya Levin: childhood in the Holocaust . rezensionen.ch, May 14, 2007; autobiography of a survivor)

- Joseph Freeman: The road to hell: recollections of the Nazi death march. Paragon House, St. Paul (Minn.) 1998, ISBN 1-55778-762-X .

- Katrin Greiser: The Buchenwald death marches. Eviction, liberation and traces of memory. Wallstein, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-8353-0353-9 .

- Network for Democratic Culture e. V. (Ed.): Deported, tormented, exploited, driven out. Network, Wurzen 2002, ISBN 3-9808903-2-5 .

- Martin Bergau : Death March to the Amber Coast. The massacre of Jews in Palmnicken, East Prussia, in January 1945. Contemporary witnesses remember . Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2006, ISBN 3-8253-5201-3 .

- Erich Selbmann: The long night. Novel. 4th edition. Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Halle 1979.

- Heimo Halbrainer, Christian Ehetreiber (ed.): Death march on Eisenstrasse 1945. Terror, scope for action, memory. Human action under constrained conditions . CLIO - Association for history and Educational work, Graz 2005, ISBN 3-9500971-9-8 .

- Ernö Lazarovits, Heimo Halbrainer, Ingrid Hauseder: My way through hell: a survivor tells of the death march . History of the Homeland Publishing House, 2009, ISBN 978-3-902427-65-6 .

- Christine Schmidt: April 1945 in Tharandt. In: Around the Tharandt Forest. Official journal of the city of Tharandt. Edition 02, Volume 13, February 15, 2011, pp. 8–9.

- Between Harz and Heide. Death marches and evacuation transports in April 1945 . Edited by Regine Heubaum and Jens-Christian Wagner i. A. the Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora Memorials Foundation and the Lower Saxony Memorials Foundation. Wallstein, Göttingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-8353-1713-0 .

- Jens-Christian Wagner: Inferno and Liberation. Auschwitz in the Harz Mountains . In: Die Zeit , No. 4/2005

- Martin Clemens Winter: Violence and memory in rural areas. The German population and the death marches , Metropol-Verlag, Berlin, 2018, ISBN 978-3-86331-416-3 . (Dissertation)

- Martin Bergau: The boy from the Amber Coast: experienced contemporary history 1938 - 1948. With a foreword by Michael Wieck and with documents about the Jewish death marches in 1945 . Heidelberg: Heidelberger Verlags-Anstalt, 1994

Web links

- Brandenburg Memorials Foundation

- LZPB Thuringia (PDF; 4 kB)

- Flossenbürg Memorial

- Text death march Flossenbürg

- Memorial to the massacre on the Präbichl

- Death marches through the western Harz

- Death marches during the evacuation and partial evacuation of the Dachau, Kaufering and Mühldorf concentration camps at the end of April

- The last way of the concentration camp prisoners: The end of the concentration camps around Landsberg / Kaufering in 1945

- Website about the death march from Dachau

- BR2 wide angle: broadcast on the death march from the Flossenbürg concentration camp ( memento from May 7, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- Andreas Wagner: Death March. The evacuation and partial evacuation of the Dachau, Kaufering and Mühldorf concentration camps at the end of April 1945 ; 1995

- Uwe Fentsahm: The "evacuation march" from Hamburg-Fuhlsbüttel to Kiel-Hassee (April 12-15, 1945)

- (Educational) material on the death marches (learning from history)

- The death march stele in Weimar

- The death march to Volary

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): Encyclopedia of National Socialism . 1997 ff, ISBN 3-608-91805-1 , p. 759.

- ↑ Katharina Hertz-Eichenrode (Ed.): A concentration camp is cleared. Prisoners between annihilation and liberation. Bremen 2000, ISBN 3-86108-764-2 , p. 33.

- ↑ leo.org

- ↑ Katrin Greiser: The death marches of Buchenwald. Evacuation of the camp complex in spring 1945 and traces of memory. Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-8353-0353-9 , p. 10 in note 8.

- ↑ Diana Gring: The Gardelegen massacre. Approaches to the specification of death marches using the example of Gardelegen. In: Detlef Garbe, Carmen Lange: Prisoners between annihilation and liberation. Bremen 2005, ISBN 3-86108-799-5 , p. 155.

- ↑ Diana Gring: The Gardelegen massacre. P. 159ff.

- ↑ Katrin Greiser: The death marches of Buchenwald. Evacuation of the camp complex in spring 1945 and traces of memory. Wallstein, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-8353-0353-9 , pp. 133 ff. And 452.

- ↑ Karin Orth: Plans and orders of the SS leadership for the evacuation of the concentration camp system. In: Detlef Garbe: Prisoners Between Annihilation and Liberation. The dissolution of the Neuengamme concentration camp and its satellite camps by the SS in the spring of 1945 . Bremen 2005, ISBN 3-86108-799-5 , p. 36f.

- ↑ Katharina Hertz-Eichenrode (Ed.): A concentration camp is cleared…. P. 32 (with reference and map p. 72).

- ↑ Joachim Neander: Destruction by evacuation? The practice of dissolving the camps - facts, legends and myths. In: Detlef Garbe, Carmen Lange (ed.): Prisoners between annihilation and liberation. Bremen 2005, ISBN 3-86108-799-5 , pp. 45f; Delivered with ISBN 3-86106-779-5 .

- ↑ Karin Orth: Plans and orders of the SS leadership for the evacuation of the concentration camp system. P. 34.

- ↑ Daniel Blatman: The Death Marches…. P. 1068 in: Ulrich Herbert, Karin Orth, Christoph Dieckmann: The National Socialist Concentration Camps. Fischer TB, Frankfurt 1998, ISBN 3-596-15516-9 .

- ↑ Karin Orth: Plans and orders of the SS leadership for the evacuation of the concentration camp system…. Pp. 33-44.

- ↑ Daniel Blatman: The Death Marches…. P. 1069.

- ↑ Karin Orth: Plans and orders of the SS leadership to clear the concentration camp system, p. 39.

- ^ Daniel Jonah Goldhagen: Hitler's willing executors. Paperback edition Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-442-75500-X , p. 418.

- ↑ Daniel Blatman: The Death Marches…. P. 1076 / Regarding the order: Herbert Diercks , Michael Grill: The evacuation of the Neuengamme concentration camp and the catastrophe on May 3, 1945 in the Bay of Lübeck. A collective review. In: End of War and Liberation. Bremen 1995, ISBN 3-86108-266-7 (Articles on the History of National Socialist Persecution in Northern Germany 2/1995) pp. 175–176.

- ↑ Christina Weiss in: Katharina Hertz-Eichenrode (Hrsg.): A concentration camp is cleared. P. 11.

- ↑ Karin Orth: The system of the National Socialist concentration camps Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-930908-52-2 , p. 332.

- ^ Daniel Jonah Goldhagen: Hitler's willing executors. Chapters 13 and 14.

- ↑ Eberhard Kolb: The last phase of the war…. P. 1133.

- ↑ Karin Orth: Plans and orders of the SS leadership to clear the concentration camp system, p. 35.

- ↑ Eberhard Kolb: The last phase of the war…. In: Ulrich Herbert, Karin Orth, Christoph Dieckmann: The National Socialist Concentration Camps. Fischer TB, Frankfurt 2002, ISBN 3-596-15516-9 , p. 1135.

- ↑ Discussion of new research results on death marches ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) International Tracing Service , its-arolsen.org, accessed on December 1, 2011.

- ↑ Gerda Weissmann-Klein: Nothing but the naked life Gerlingen 1999.

- ↑ Feldscheune Isenschnibbe Memorial Gardelegen: On the history of the Gardelegen massacre. In: Homepage of the Isenschnibbe Feldscheune Gardelegen memorial. August 1, 2017, accessed December 29, 2019 .

- ↑ Constanze Werner: Concentration camp cemeteries and memorials in Bavaria, Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 2011, here 15-36.

- ↑ Information from the public prosecutor's investigation files at the Munich Regional Court I, 119 b u. JS 3/71.

- ↑ Randolph L. Braham : The Politics of Genocide. The Holocaust in Hungary. Volume 1. Guildford: Columbia University Press, New York 1981, ISBN 0-231-05208-1 , pages 335-337; Daniel Blatman: The Death Marches. The Final Phase of Nazi Genocide. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London 2011, ISBN 978-0-674-05049-5 , pp. 65-66. Erhard Roy Wiehn (ed.): Forced labor, death march, mass murder. Memories of surviving Hungarian slave laborers at the Bor copper mine in Yugoslavia 1943-1944. Hartung-Gorre, Konstanz 2007, ISBN 978-3-86628-129-5 , pp. 44-46, 53, 54, 78, 79 and 81.

- ^ Miklós Radnóti: forced march . das-blaettchen.de; accessed on March 17, 2016.