Eucharist

The Eucharist ( "thanksgiving"; . Greek εὐχαριστέω eucharistéo , I say thanks'), and the Lord's Supper or the Lord's Supper , Holy Communion , Eucharist , Most Holy Sacrament [the altar] , in some free churches breaking of bread , in the Eastern Churches sacred or divine liturgy called, is Depending on the denomination, understood as a sacrament or a sign . It is related to the Lord's Supper , which, according to the presentation of the Gospels and 1 Corinthians, Jesus celebrated with his disciples shortly before his suffering and death, and is interpreted either as a bloodless visualization of the sacrifice of the cross or as a celebration of the remembrance of Jesus' death.

In addition, at the Eucharist, the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ are proclaimed as a salvation event . Jesus Christ is present in the community he has given . The teaching of the various denominations differs in terms of the manner of this presence - in his word, in faith in him or in the gifts of bread and wine.

origin

In the weeklong Passover, Judaism commemorates Israel's departure from Egypt and celebrates it. The prelude to this is the Seder : an evening domestic feast with the whole family, which follows a precise process. This is traced back to Ex 12.3–20 EU . Each father of the family reads the Haggadah (story) from the excerpt, speaks the blessing over the symbolic food - sacrificial lamb, unleavened bread ( matzo ), bitter herbs ( hyssop ) and wine - and then distributes them to those present. In this tradition, on the eve of his death on the cross, Jesus celebrated the Jewish Seder meal with his disciples and made bread and wine permanent signs of his presence in the Christian community.

The last meal of Jesus and the early Christian meal fellowship are represented and designated differently in the New Testament (NT) . First, after a satiety meal, following the example of Jesus, the blessing words were spoken over bread and wine. Soon these were separated from the meal - which became independent as agape - and combined with the Sunday prayer service in the morning. This connection of literal worship and Eucharistic celebration can be found for the first time in detail in Justin the Martyr († 165), who describes a Christian worship service with reading order , sermon , intercessory prayer , kiss of peace and supper. The Traditio Apostolica , often attributed to Hippolytus of Rome († 235), also describes an early form of the Eucharist. Overall, however, the lines of development in the first centuries are largely unclear: In addition to an episcopal parish eucharist as the ideal form, various forms of presbyter, house and group masses developed.

In more recent research, the influence of Greco-Roman meal customs on the development of the Eucharist is again being discussed more intensely. Until the middle of the 3rd century the form of the meal was based on well-known institutions of the Greco-Roman world ( symposium ; mealers of ancient associations ).

Lukas Bormann deals with ritual theoretical aspects in connection with cognitive scientific ritual theories. He identified seven aspects of the early Christian Lord's Supper:

- Ritual media ("bread and wine")

- Basic functions of the ritual ("Last Supper and Agape Meal")

- Ritual acts ("breaking bread", "holy kiss")

- Performative utterances ("Our Lord, come!", "Supper")

- Spaces and times

- Actors of the ritual

- Exclusion and inclusion ("participants, exclusion")

The ritual media are bread and cups. The content of the cup is a mixture of water and wine. Both ritual media are present in the everyday life of ancient people and therefore only have a low level of sensual attractiveness. Because ritual theories of cognitive science assume that there is a proportional relationship between effort and emotional intensity: the more extraordinary and complex, the higher the potential for intense, emotional experience. Bread and wine, however, have different meanings from everyday understandings (bread as body and wine as blood), which makes them counter-intuitive representations. In the Traditio Apostolica, the ritual media are supplemented, for example by oil, cheese and olives.

In addition to the physiological necessity (to satisfy hunger), the basic functions of the filling communal meal (agape meal) are to enable the perception of a community as a group, as well as social-charitable and missionary functions (as becomes clear in the Didaskalia Apostolorum ). The most important function of the Lord's Supper is synchronization, i.e. enabling a group to gather in the same place at the same time in order to stabilize the group identity.

The ritual acts are words of blessing over the ritual media, breaking bread and the holy kiss. The breaking of bread is linked to the interpretation of Christ's gift of life and the expression "breaking bread" can be used as a communal meal as a whole. The holy kiss is not explicitly associated with the Lord's Supper in the New Testament, but Justin and the Traditio Apostolica mention it in connection with the Lord's Supper. The ritual acts mentioned are neither time-consuming nor costly, which is made possible by the high frequency of weekly meetings.

The performative expressions of thanks do not relate to the ritual media, but to their effect, which they develop in the rite. The eschatological call "Lord, come!" / "Our Lord, come" originally belonged in the congregation meeting (1 Cor. 16:22), but in the Didache it is connected with the Lord's Supper. The call serves the ritual visualization of Kyrios.

Rooms and times are initially flexible. There are no special sacred spaces to which the practice of the rite was restricted. The Lord's Supper takes place on the day after the Sabbath, according to the Jewish schedule, either in the evening or not until the next morning.

The actors are not yet defined in the New Testament, the Didache mentions prophets as the only status group that has the right to longer eucharistic prayers. Ignatius demands the presence of a bishop so that the ritual can be considered reliable. Justin has a chief, supporting deacons, brothers, and the people. The Traditio Apostolica also has a differentiated office structure of bishop, presbyter and deacon. In the Syrian Didascalia, too, the bishop presides over the Lord's Supper.

Exclusion and inclusion are not explicitly addressed in the New Testament, but it is assumed that the participants belong to the group. Only the Didache and the Traditio Apostolica make baptism a prerequisite for participation in the Lord's Supper and thus exclude the unbaptized.

Main types

In the course of the history of Christianity, the denominations and beliefs differed among the different denominations :

- The Orthodox Churches, the Roman Catholic Church and the Anglican Community mainly call communion with Paul of Tarsus ( 1 Cor 11:24 EU ) the Eucharist . One speaks here, among other things, of the sacrament of the altar , with regard to the conversion (consecration) from the sacrifice of the Mass , with regard to the reception of the sacrament of communion .

- The Protestant churches speak of the Lord's Supper . They identify it with the last supper of Jesus on the eve of his death ( Mk 14,17 EU , 1 Cor 11,23 EU ) and also understand it as a sacrament. Often one speaks here with 1 Cor 11.20 EU also of the Lord's Supper and thus emphasizes his institution by Jesus himself. The term table of the Lord is also related (τράπεζα κυρίου, 1 Cor 10.21 EU ).

- With Acts 2.46 EU this is described as the breaking of bread . Some free churches only use this expression to emphasize the not necessarily sacramental framework of an early Christian agape celebration .

In the history of Christianity, denominationally different teachings on the meaning of the meal have been associated with the names :

- true and lasting real presence of Christ as priestly visualization of the one sacrifice of Christ through transubstantiation (Roman Catholic)

- Real presence of Christ's body and blood through the consecration words without repetition of the sacrifice (Lutheran, Anglican, Methodist)

- Spiritual presence of Christ in word and faith without changing the elements that are and remain symbols, images, signs for it (reformed and partly free church)

liturgy

procedure

Despite all the differences, there are many elements in the liturgy that - in a more or less fixed form and order - occur in most denominations. Many of these elements have been handed down from liturgies of the second and third centuries:

- Admission of guilt and absolution

- Preface (great thanksgiving prayer)

- Sanctus (holy, holy, holy) with Benedictus (praised be he who comes)

- Anamnesis (memory)

- The words of the institute report with consecration and epiclesis

- Mysterion (secret of belief)

- Our Father

- Peace greeting

- Agnus Dei (Lamb of God)

- Communion (enjoyment, also called usufruct or consumption, of the holy gifts by their recipients)

- Oration (postcommunio)

- Blessing and discharge

In the Orthodox, Catholic and Anglican liturgy, the Eucharistic liturgy always forms a unit with a preceding Liturgy of the Word . The evangelical Lord's Supper, on the other hand, is often only held occasionally after the regular Sunday service.

The Eucharistic figures bread and wine

In all churches, bread and wine are the elements used in the celebration of the Eucharist, given and received at communion . In the parlance of the Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Anglican and Old Catholic Churches, they are also referred to as "Eucharistic elements" or "Eucharistic gifts".

In Judaism, unleavened bread and wine are among the dishes that are served in Jewish families on Seder Eve, the eve of the Passover festival. In the Tanakh Melchizedek , the king and priest of Salem, meets Abram with bread and wine ( Gen 14.18 EU ); this motif is taken up in Hebrews 7: 1–17 EU . According to synoptic tradition, Jesus celebrated the Jewish Seder meal with his disciples on the day before his death on the cross and determined bread and wine to be permanent signs of his presence in the Christian community ( 1 Cor 11 : 23-26 EU ).

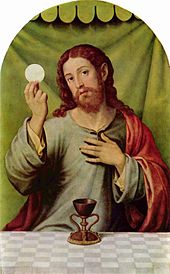

The Eucharistic gifts of bread and wine as well as ears of wheat , vines and grapes are often represented symbolically in Christian iconography , in pictorial, figurative or ornamental design.

loaf

The Latin Church , the Lutheran Churches and the New Apostolic Church traditionally use hosts made from unleavened, i.e. unfermented dough without baking yeast or baking powder. You are following the Jewish Seder meal. Orthodox, ancient Near Eastern, Uniate, Reformed and Free Churches use white bread made from ordinary bread dough, which is sometimes provided with special symbols. According to Mt 13.33 EU and Lk 13.21 EU, leaven is a parable for the kingdom of God. The Anglican Church and some free churches do not specify the type of host or bread.

In the Orthodox churches of the Byzantine rite , the middle part of a round, leavened loaf of bread embossed with Christian symbols during baking ( Prospore ) is used. The middle part is called the "lamb". Only this “lamb” and the wine are consecrated . The body and blood of Christ are mixed in the cup and then given to the believers. Hand Communion, which is now possible again in the Latin Church , is not known here; the faithful receive communion on the mouth with the help of a golden spoon. If there is a remainder, it will be consumed by the deacon or priest after giving communion. For the sick Communion is always a small piece of the consecrated Lamb that-consecrated with a drop of wine is soaked in, the tabernacle similar artophorion kept. Adoration and adoration of the Eucharist outside the Divine Liturgy is not common.

Like the “lamb”, which is consecrated later, some other parts are also cut out of the prosphere with the help of a knife called a “lance” during proscomidia ; This name recalls the lance that a Roman soldier thrust into the lifeless body of the crucified Christ according to the account of the Gospel of John to determine whether he was already dead. When the “lance” is pierced for the first time, the deacon asks the priest: “Slaughter, master!”; here the symbolism of sacrifice becomes clear.

The other parts of the bread mentioned above represent the Blessed Mother , the saints and all living and deceased believers during the liturgy , but are not consecrated. After communion has been given, they are also placed in the chalice and consumed. The remaining, outer part of the loaf and additional pieces of bread are blessed after the consecration of the "lamb" and the wine, but not consecrated. This so-called antidoron is distributed to the faithful after the liturgy, including those who do not belong to the Orthodox churches. They either take it straight away or take it home with them - for sick or elderly people staying at home.

Wine

Until the 19th century, apart from a few communities like the Enkratites , the Eucharist was celebrated with wine everywhere ; At that time, grape juice could not have been preserved in most of the seasons anyway. Orthodox, Anglican and Old Catholic churches all use wine to this day. The Reformation churches deviate from this, especially where children are allowed to take part in the Lord's Supper or when the Lord's Supper is celebrated in hospitals and retirement homes. In the Roman Catholic Church, grape must is only permitted in place of wine in narrowly defined exceptional cases.

The sanctification movement and the related abstinence movement in the USA then began, out of consideration for children and alcoholics , to serve grape juice rather than wine with the Lord's Supper. This is customary today in the Methodist Church, in many churches of the Reformed tradition and in some United regional churches or as an exception. Especially evangelical proponents of grape juice argue that the NT texts speak of bread, but not of wine as an alcoholic drink, but of the chalice or the “plant of the vine”. In the regional churches of the EKD , the free choice between grape juice and wine at the Lord's Supper has been a widespread or almost universal practice for decades. Reasons are above all possible health restrictions of the recipient or the admission of the children's evening meal. This applies equally to Lutheran, Reformed and United regional churches.

With the Evangelists Matthew and Mark it is said to drink “from” the plant of the vine, with the Evangelist Luke it is said “from” the vine. The Evangelist John speaks of "the water of eternal life". So it can be historically assumed that at least some of the celebrations took place with water. This is also suggested by the historical documents up to the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 , which determined the content of the chalice.

Proponents of wine object that Christ certainly did not use grape juice when instituting the Lord's Supper because it could not be preserved and wine is still used at the Passover meal to this day. A Lord's Supper with grape juice is not in the spirit of the founder and does not give communicants any certainty that they will receive the body and blood of Christ for the forgiveness of sins. However, it was also possible to use raisin wine during the seder evening, so that children can also take part.

In the eastern churches , the wine (red wine is common here) is warmed to approximately body temperature by adding a small amount of boiling water ( Zeon ).

Forms of administration

In the Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Anglican and most of the Reformation churches, Jesus Christ is understood as the actual giver, who gives communion through the priest , deacon or other communion giver. In these churches, therefore, bread and wine are donated individually to each recipient and not by passing on the host bowl or chalice from one recipient to the next.

In the New Apostolic Church, wafers that have been singled out by a priest or apostle and that have been sprinkled with three drops of red wine after baking are distributed to the faithful. This can only be done by ordained clergymen who belong to the priestly office level or who are apostles of the New Apostolic Church.

According to the understanding of most churches in the evangelical tradition, the risen Jesus Christ gives himself in the Lord's Supper in his body and blood given for all through his promised word with bread and wine. (Formulation of the Leuenberg Agreement ). Even in these churches, a Lord's Supper is only fully valid after it has been instituted by an ordained pastor. Only then can lay people , such as church councils or elders, be involved in the donation. In Reformed churches, parishioners can pass bread and wine on to one another. This practice is also used as the Agap meal in other Protestant communities, but there is usually not considered a fully valid Lord's Supper.

In most denominations, the believers are offered both bread and wine (receiving communion in both forms) . In the Roman Catholic Church, cup communion for believers has been permitted again since the Second Vatican Council and even recommended: “Communion gains its full symbolism if it is given under both forms. In this form the sign of the Eucharistic meal is expressed in a more perfect way ”, but in the Sunday church service for the faithful the exclusive receipt of bread is the rule; According to the teaching of the Catholic Church, the whole of Christ is present in each of the two forms.

When receiving communion under both forms, different forms are practiced: drinking from the common chalice or from individual goblets, the intinctio , in which the giver dips the host into the chalice and the recipient thus receives communion under both forms, in the form of Hosts on which three drops of wine are sprinkled, or in the Orthodox liturgy the offering of the mixed offerings with a spoon.

Special sacred implements are often used to celebrate the Eucharist : chalice and paten . In the Eastern Churches there are other special devices, including a knife called a "lance" for cutting the bread and golden spoons for distributing the mixed elements. In many Protestant congregations, especially when there are large numbers of communicants, a wine jug is used to refill the goblet. Sometimes the wine is distributed there in additional small individual goblets for hygienic reasons.

Admission to communion

children

The admission of children to St. Communion and the Lord's Supper are handled differently:

- In the Orthodox Churches, children baptized Orthodox are admitted to communion regardless of their age.

- The Reformed churches in Switzerland have been admitting children for decades. More and more Protestant churches outside of Switzerland are adopting this custom, including in Germany: The Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau gives its parishes the freedom to admit children to the Lord's Supper; however, they are said to have been informed of its significance (for example in religious instruction ). In the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria , too, since 2000 the regional synod has recommended that baptized children be given the Lord's Supper; however, implementation is left to the municipalities. The regulation in the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Saxony is also comparable . The Evangelical Church AB in Austria was the first Lutheran church to introduce communion open to children across the board.

- In the Evangelical Methodist Church , the children's evening meal is permitted. It is justified with the general call to the Lord's table, who does not exclude anyone if he wants to participate. It is the responsibility of the parents to ensure that the children learn the meaning of the sacrament in good time.

- In the New Apostolic Church and in most of its offshoots, all baptized and sealed believers are admitted to Holy Communion from infancy onwards. Those baptized from other denominations can also take part in the sacrament celebrations.

- In the Catholic Church, children usually go to first communion between the ages of six and twelve, but if the child or the family so wishes, this can also be done earlier.

Open Supper

In churches that practice open communion or open communion, non-members are also permitted without further restrictions.

- The United Methodist Church knows no restrictions on admission to the Lord's Supper. Anyone who wishes can participate. She argues that the host is Jesus Christ himself and therefore it is not for anyone to impose restrictions.

- Any interested adult can take part in communion of the Christian community without any further requirements.

- All baptized Christians who are also allowed to receive the Eucharist or the Lord's Supper in their own church are admitted to the Protestant regional churches. In some Protestant regional churches, the Lord's Supper is also given to the unbaptized when they come.

- The Seventh-day Adventists practice open communion, in which everyone can participate who feels properly in faith to Jesus Christ.

- In the Old Catholic Church in Germany , the invitation to the Eucharist applies to all baptized people who share the belief “in the bodily presence of the risen and exalted Lord in the Eucharistic figures”.

- In the Reformed Churches in Switzerland , everyone who seeks communion with Jesus Christ and communion in the church are invited to the Lord's Supper.

- In many Evangelical Free Churches, everyone is admitted who see themselves as born again Christians .

- Some Evangelical Free Churches allow those who have been baptized on the basis of a personal confession of their faith in Jesus Christ (baptism of faith ).

- The Association of Apostolic Congregations allows all who believe in the sacrificial death of Christ to attend the Lord's Supper.

- The New Apostolic Church allows all Christians baptized "appropriately" to take part in the Lord's Supper as guests.

Closed communion

For churches that practice closed communion, admission to communion is limited to members of the church concerned and members of churches with which it is in full church fellowship.

- In the Roman Catholic Church, the faithful with first communion and Christians of the churches united with Rome are allowed to receive communion. Therefore, members of the Protestant, Orthodox and Oriental churches are usually not invited to receive communion. If members of Orthodox and Oriental churches voluntarily ask to receive communion, it may be given to them. Baptized members of other churches may legitimately be given communion only with the consent of the diocesan bishop or in emergencies and in danger of death, if they previously express their faith in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. The condition of grave sin prevents communion from being received (for example in the case of divorced and remarried persons, with the added problem of public persistence in this condition).

In February 2018, the German Bishops' Conference decided to issue a handout for married couples of different denominations, according to which Protestant spouses could receive communion in individual cases and under certain conditions if, after “careful examination in a spiritual conversation with the priest or another with the Pastor commissioned person have come to the conscience judgment to affirm the faith of the Catholic Church and to end a “serious spiritual emergency” and to satisfy the longing for the Eucharist “.

- In Orthodox Churches, only baptized Orthodox Christians can receive communion; Small children receive the holy gifts without preparation, older children and adults if they are prepared according to local custom, for example through sobriety, abstinence, preparatory fasting , regular confession and participation in the preceding evening or night service, alternatively also through private reading of communion prayers . By agreement with the Holy See , some Eastern Churches also allow Roman Catholic Christians to receive Communion if necessary.

- In Lutheran churches with an old denominational character , such as the Independent Evangelical Lutheran Church (SELK), only Christians of their own church are admitted to the sacraments after early communion or confirmation , and those Christians who belong to a church with which full church fellowship has been established.

- In some free churches only Christians of their own church are admitted.

Most churches that practice closed communion give Christians of other denominations the opportunity to receive communion in an emergency.

Interdenominational communion

Many churches also allow all members of other denominations to take part in the Lord's Supper ( intercommunion ). It has also been agreed between some churches that there can also be joint communion celebrations ( intercelebration ). Such a communion fellowship exists

- between the Lutheran, Reformed and other Protestant churches in Europe that are affiliated to the Leuenberg Agreement

- between the Utrecht Union of Old Catholic Churches and the Anglican Community on the basis of the Bonn Agreement of 1931

- between the Old Catholic Church of the Netherlands and the Old Catholic Church of the Mariavites

- between the Anglican community and the Indian Orthodox Mar Thoma Church

- between the US member churches in Churches Uniting in Christ

- between the churches in the United States that signed the Formula of Agreement (1997): the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA), the Reformed Church in America (RCA), the Presbyterian Church (USA) and the United Church of Christian (UCC)

- between the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) and the United Methodist Church (UMC)

- between the member churches of the Porvoo fellowship

Between the Old Catholic Church in Germany and the member churches of the Evangelical Church in Germany there has been mutual admission to the Lord's Supper since 1985; likewise between the Church of England and the Methodist Church of Great Britain in Great Britain.

Although there is no full communion communion between the Catholic Church and the Assyrian Church of the East , Catholics of the Chaldean Rite and believers of the Assyrian Church are permitted to partake in the communion of the other church under certain conditions.

Due to different views on the understanding of the priesthood, a common Eucharistic celebration by Catholic and Protestant Christians is not possible according to the Catholic view. For the Old Catholic and Anglican churches, according to the Roman Catholic Church, the obstacle is the lack of recognition of episcopal ordinations by the Pope.

An important step on the way to a common Christian understanding of the Lord's Supper is the Lima Declaration of the World Council of Churches . An encouraging sign for a common understanding is that the “validity” of the Lutheran Last Supper in the sense of a real presence of Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI. ) As chairman of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith was put out of dispute.

Eucharistic hospitality

The current theological discussion about the possibility of communion in the Lord's Supper, especially between Protestant and Roman Catholic Christians, is conducted under the term “Eucharistic hospitality” or “hospitality”. Evangelical and also some Catholic theologians plead for this hospitality at the Lord's Supper or the Eucharistic celebration, since it is ultimately Christ himself who invites all Christians. In the EKD's 20 regional churches, all the baptized are invited to the Lord's Supper. The attitude of the Roman Catholic Church, on the other hand, is that there can be no “general Eucharistic hospitality” as long as there is no church fellowship (in the understanding of the sacraments , especially the Eucharist and the Sacrament of Orders , and apostolic succession ). The question of “Eucharistic hospitality” for married couples in which one partner belongs to the Roman Catholic Church arises particularly urgently.

Controversial Kirchentag liturgy

In the run-up to the Ecumenical Church Congress 2010 in Munich, a common Eucharistic celebration was clearly rejected by the leadership levels of both churches. In the opinion of the Evangelical Lutheran Bavarian regional bishop Johannes Friedrich and Archbishop Reinhard Marx, such events harm the ecumenical movement.

to teach

The doctrines of the Eucharist and the corresponding liturgies of the Christian denominations were developed and established in the Orthodox Churches up to around 1000, in the Roman Catholic and Protestant Churches in a mutual delimitation of Holy Mass and Lord's Supper up to around 1600.

Patristic

Ignatius of Antioch († 107–110) called the Eucharist a "medicament of immortality " and wrote in his letter to the Smyrneans :

“They keep their distance from the Eucharist and prayer because they do not confess that the Eucharist is the flesh of our Savior Jesus Christ, who suffered for our sins and which the Father raised in his goodness ... Let only that Eucharist count as that lawful, which is carried out under the bishop or by the person appointed by him. Wherever the bishop appears, there is also the people, just as where Jesus Christ is, there is also the Catholic Church. One cannot baptize or celebrate the love supper without the bishop; but whatever he thinks is good, that is also pleasing to God, that everything that happens may be safe and lawful. "

In the letter to the Philadelphians he wrote:

“Make an effort to celebrate only one Eucharist; for there is only one flesh of our Lord Jesus Christ and only one cup for union with his blood, only an altar, as only a bishop is in connection with the presbytery and deacons, my fellow servants, so that whatever you do, you do according to the will of God. "

The Didache from around 100 reads: “On every gentleman's day, when you come together, break the bread and say thanks, after you have previously known your wrongdoings so that your sacrifice may be pure. But no one who has a dispute with his neighbor should come together with you until they have been reconciled, so that your sacrifice is not desecrated. For this is the word spoken by the Lord: 'To offer me a pure sacrifice in every place and every time; for I am a great King, says the Lord, and my name is wonderful among the peoples. "(cf. Mal 1,11.14 EU )

Justin the Martyr (c. 110–165) understood bread and wine in Holy Mass as the body and blood of Jesus. It is the oldest surviving written source that attempts to formulate the doctrine of transubstantiation. At the same time, however, it is very controversial whether and to what extent the sacrificial character can be found in him in the Eucharist, as it was later formulated in a binding manner by the Roman Church. For he says that prayer and thanksgiving are the only perfect sacrifices that please God:

“And when the ruler has given thanks and all the people have given their approval, those who are called deacons give each of those present to share in the bread and wine mixed with water over which the thanksgiving was pronounced and to them who are absent, they carry away a part. And this food is called the Eucharist by us, in which no one is allowed to attend unless he believes that the things we teach are true, and who is washed and renewed with baptism for the forgiveness of sins and who lives so, as Christ set it to be. For we do not receive this as the usual bread and drink; but in the same way as Jesus Christ our Savior, who became flesh as the word of God and had both flesh and blood for our salvation, we have been equally taught that food which is blessed by the prayer of His word and from which our blood and flesh are nourished by transformation, which is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who became flesh. "

Aurelius Augustine combines his philosophical reflections on the sign with a doctrine of the Eucharist that was completely new at his time:

“The Eucharist, bread and wine are called sacraments because one sees something different in them, while recognizing something else. What one sees has a physical form, what one recognizes has a spiritual content. ' The Eucharist [...] is not just one of many signa [sign, author's note], but it is one of the signa sacra, since bread and wine are first transformed into a 'visible word'. "

Irenaeus of Lyon wrote in Adversus haereses (around 185) about the sacrifice of the Church:

“But how can they again say that the flesh is rotten and has no part in life when it is nourished with the body and blood of the Lord? So may they change this teaching or no longer offer the mentioned gifts! But our teaching is consistent with the Eucharist, and the Eucharist in turn confirms our teaching. For we sacrifice to him from his own, appropriately proclaiming the indissoluble union of flesh and spirit. For just as the bread that comes from the earth, when it receives the invocation of God, is no longer ordinary bread, but the Eucharist, which consists of two elements, an earthly and a heavenly one, so our bodies also belong when they receive the Eucharist, no longer of perishability, but have the hope of resurrection. "

Hippolytus of Rome (around 170–235) narrated a detailed Eucharistic prayer (prayer) in his Traditio Apostolica .

Cyprian of Carthage (around 200-258) emphasized in his writings (especially ep. 63) the sacrificial character of the Eucharist. The priest makes a real sacrifice. Cyprian also testifies to the practice of the daily celebration of the Eucharist and the close connection between the Eucharist and the position of the clergy: the clerics are paid mainly from the gifts that the faithful bring to the Eucharist.

Catholics

The Eucharist is the main part of Holy Mass in addition to the proclamation of the Word of God. The entire Holy Mass is also called the Eucharist or celebration of the Eucharist . In it the Passover mystery , the mystery of redemption through the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, is brought to mind and celebrated.

The Roman Catholic Church teaches the real presence of Jesus Christ in the forms of bread and wine in the Eucharist. When the priest, who acts with it in persona Christi , utters the words of institution “This is my body” and “This is my blood” during the prayer ( consecration ), the mysterious change ( transubstantiation ) of the substance of bread and wine into the real ones takes place Body and true blood of Christ. Christ is truly present in the consecrated host and remains so even after the actual sacrifice. That is why consecrated hosts are kept in the tabernacle and are used for communion for the sick and dying (“ food for the journey ”) as well as for adoring veneration by the faithful.

According to the teaching of the Council of Trent , the sacrifice of the Mass and the sacrifice on the cross are identical: “The offering is one and the same; the same one who sacrificed himself on the cross is now sacrificing himself through the service of the priests; only the way the sacrifice is made is different. ”The council describes the exact relationship between the sacrifice of the Mass and the sacrifice on the cross as repraesentatio (“ making things present ”), memoria (“ memory ”) and applicatio (“ giving ”). The Roman Catechism adds the instauratio ("renewal"). As a sacramental representation of the sacrifice of the cross, let it be his living, objective visualization, which turns the graces that Christ deserved on the cross to people. At the same time, this fulfills Jesus' request: “Do this in memory of me.” The council understood remembrance as an objective event, not as a mere commemoration: “Whoever says that a real and real sacrifice is not made to God at Mass, or that the act of sacrifice consists of nothing else than that Christ should be given to us for food, he was excluded [from the church]. "

According to Catholic teaching, Jesus Christ is contained both under the form of bread and under the form of wine, whole and alive with body and blood, soul and deity. Thus the communion of the community is not absolutely necessary under both forms. For this reason and for hygienic reasons, the lay goblet was more and more avoided since the High Middle Ages and finally discontinued; only the priest drank the Eucharistic wine. Today the reception of communion is possible again in both forms and is "highly recommended" by the church, especially on certain occasions: The chalice communion is received by bridal couples in their bridal mass, religious when they are made and consecrated virgins when they are consecrated, and newly baptized adults in mass that follows their baptism and adults at Confirmation. For the mass of the Last Supper on Maundy Thursday it is expressly provided for in the missal; for the celebration of Easter Vigil it is strongly recommended by the Vatican. The priest presiding over a holy mass must always communicate under both forms.

The Eucharist is one of the seven sacraments . According to the teaching of the Catholic Church, the sacrament works ex opere operato through its correct, institution-appropriate execution . Since Jesus' commission to share bread and wine in his memory was given to the apostles, the consecration is only permitted to ordained priests and is only valid when they are carried out. Because through their consecration they are representatives of the bishops, who in turn are successors of the apostles through apostolic succession .

The prerequisite for receiving communion is belief in the real presence of Christ. That is why small children (except in the Catholic Eastern Churches) are not allowed to communicate, as they cannot yet distinguish the body of Christ from normal bread. Furthermore, the communicator must be free from serious sins and, if necessary, be reconciled to God in the sacrament of penance before communion ; Eucharistic sobriety should also be observed at least one hour before receiving communion .

The Roman Catholic Church recommends the daily celebration of Holy Mass and, if possible, the daily reception of Holy Communion. Receiving them increases the love of God, thereby protecting against attachment to sin and bringing about the forgiveness of lighter sins. When the people of God united in the Church receive the body of Christ at the Lord's supper, they themselves become “the body of Christ”.

See also: Eucharistic Adoration , Eucharistic Procession , Eucharistic Blessing , Mass Offering, and Ecclesia de Eucharistia .

Orthodox

Orthodox churches believe that bread and wine are really the body and blood of Christ. The liturgy shows parallels to the Jewish temple worship. In contrast to the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, there are no words of change here . The mystery is done rather by the whole liturgy , with the invocation of the Holy Spirit through the gifts in the epiclesis is central.

A philosophical clarification of the “how” of the change is dispensed with, the term transubstantiation is not used, in some cases even rejected. The Eucharist, which the Byzantine churches also refer to as the “divine liturgy” , is also considered a sacrifice in the Byzantine rite , more precisely as the making present of the one sacrifice of Christ. The reception of the Eucharist in the Orthodox Church with non-Orthodox Christians is considered impossible because the Orthodox faith of the participants of the Eucharist (and nothing else) , by definition, the church 's and non-Orthodox thus almost automatically transgress the Orthodox Church when they participated. When a believer wishes to receive the Eucharist, he usually reports to the priest the day before; this is especially true for outsiders whom the priest does not know personally.

The presence of the faithful is essential for the celebration of the Eucharist - a Eucharistic liturgy without at least one believer is not possible. The priest may celebrate the Eucharist no more than once a day, it may only take place once a day in each church building and a believer may also take part in it no more than once a day. However, the daily celebration of the Eucharist is also unusual for priests in Orthodoxy; the weekly rhythm is more common, especially the celebration on Sunday.

All baptized Orthodox Christians are allowed to receive the Eucharist, even small children, since the Orthodox Church understands “faith” primarily in the sense of a trust that even small children are capable of, less in the sense of “believing it to be true” would require developed minds. However, some churches require adult participants to make a full confession the evening before, which has led to the fact that in some Orthodox churches the adults only receive the Eucharist themselves a few times a year, while otherwise they only take part as prayers or singers. However, efforts are currently being made to make weekly reception the norm again.

Anglican

In the Church of England , soon after the Reformation, heated debates over the doctrine of transubstantiation began. At first, after Henry VIII broke with the Roman Catholic Church, the doctrine of real presence was still adhered to. But under Edward VI. the reformer Martin Bucer came to Cambridge , became a professor there and had a decisive influence on the theology of the Church of England. At that time, Bishop Thomas Cranmer had initially held a Lutheran position and his colleague Nicholas Ridley a Reformed position. Bucer tried to mediate between these attitudes, as he had done on the continent. On the one hand, he rejected a perceptible presence of Christ in the Eucharist, on the other hand, he took the view that Christ was present in the Eucharistic forms of bread and wine. Bucer made a distinction between the external and the spiritual or internal and was therefore close to the mystics in his thinking. He came to believe that the mark of the body of Christ was given to the mouth. At the same time the true body of Christ is offered to the soul . This statement by Bucers is found later in the prayers of the Book of Common Prayer and shows that he represented an independent theology. Influenced by Bucer's mystical position, Cranmer later said: "[…] is the very body of Christ inwardly by faith indeed eaten of all them that come as they ought to do, with eating nourisheth unto everlasting life."

However, Cranmer differed from Bucer because he did not exclusively use a "biblical" language. His statements therefore appear clearer and clearer:

"We say not [...] that the body of Christ is corporally, naturally and carnally either in the bread and wine or forms of bread and wine, or in them that eat and drink there-of: but we say that he is corporally in heaven only, and spiritually in them that worthily eat and drink the bread and wine. "

In his thinking, Cranmer showed similar mystical tendencies as Bucer, which becomes clear, for example, in his answer to the question whether there is a worthy and unworthy participation in the Eucharist:

"All men eat not Christ's body nor drink his blood - Christ is spiritually eaten of all faithful christian men, not only when they receive the sacrament, but continually, so long as they be members of Christ's spiritual body."

This attitude of Bucer and Cranmer was reflected in the 39 Articles of Religion of 1571, in which the attitude mentioned above is reproduced. Even today the Catechism of the Episcopal Church of the United States of America maintains this dualism: an outer form and an inner, spiritual grace. Through this recognition of both realities, the via media, as a characteristic Anglican solution, is also applied to questions of the Eucharist.

The pendulum swung back in the 19th century with the so-called Oxford movement around John Henry Newman . The real presence was emphasized again, in a way that was more closely reminiscent of the Roman Catholic conception ( Anglo -Catholicism ). Today a wide range of views is represented within the Anglican communion.

Old Catholics

According to the Utrecht Declaration of 1889, the Old Catholic Church adheres to the old (= original) Catholic faith, according to which communicants receive the body and blood of Jesus Christ themselves under the guise of bread and wine. The Eucharist is not a repetition or renewal of the unique Atonement of Christ, rather its sacrificial character consists in "that it is the lasting memory of the same" and that presents Christ's offering for the salvation of redeemed humanity.

In view of the sacrament, according to the Old Catholic view, speculation about the manner of Christ's presence in the elements of bread and wine is forbidden. Old Catholic theology therefore predominantly rejects the doctrine of transubstantiation and consubstantiation, rather emphasizing the character of the secret, the mystery.

What is decisive for the “transformation” of the elements is not the priest's speaking of the words of institution, but rather the entirety of the liturgical celebration together with the assembled community.

Communion in the Lutheran understanding

According to the Lutheran view, the Lord's Supper is a sacrament and thus a “sign and testimony” of the divine will, through which faith is awakened and also strengthened. At the same time, the sacraments also demand faith, since only faith can seize salvation in the sacrament. The confessional writings of the Evangelical Lutheran Church criticize the Roman Catholic understanding of the Eucharist with reference to the New Testament Bible passages on the sacrament of the altar. The doctrine of transubstantiation is rejected because it is a purely philosophical explanatory model and has no biblical basis. Likewise, the sacrifice of the Mass, which the priest offers to the Father in a bloodless manner, is rejected on the basis that Christ's sacrifice on the cross was made once and for all and does not need to be repeated or supplemented. A third point of criticism is the withdrawal of the lay cup.

However, the Lutheran Confessions hold fast to the real presence of Christ's body and blood in and under bread and wine in the consecrated elements. Through the consecration by the pastor, the bread and body of Christ, the wine and blood of Christ are united in a sacramental unity. That is, at the sacrament, bread and wine are naturally present as that, while Christ's body and blood are heavenly but not carnal. This supernatural presence does not arise through belief in it, but is given through sacramental union. The real presence is established through the omnipresence of Jesus Christ; therefore bread and wine are encompassed in the presence of Christ. This is possible because in Christ the human and the divine natures are personally united, so that his body is not earthly but heavenly in “the quality of the rights of God” and is consumed.

In the Independent Evangelical Lutheran Church only ordained pastors are allowed to administer Holy Communion, since in the act of consecration they stand in the place and commission of Christ ( in persona Christi ). In Lutheran regional churches, with the exception of Saxony, vicars and preachers , i.e. non-ordained persons, are also allowed to administer the Lord's Supper.

For the Lutheran churches, belief in the real presence of the body and blood of Christ means that believers as well as unbelievers receive Jesus' body and blood in the Lord's Supper (manducatio impiorum) . Those who do not believe that they really have received Christ's body and blood and thus the forgiveness of their sins would take the meal for judgment and would be guilty of the body and blood of the Lord (cf. 1 Cor 11 : 27-29 LUT ). It is not the faith of the recipient that makes the sacrament , but the sacrament creates and strengthens the faith of the recipient. Christ's promise “This is my body - this is my blood” is the basis for the presence of Christ in the elements of bread and wine, independent of faith or unbelief: This could strengthen the participants in their assurance of salvation .

In the period up to the Enlightenment the consecrated gifts were also kept in the monstrance and a sacrament niche or a tabernacle in Lutheran churches and were differentiated from non- consecrated hosts. Luther and the “ Gnesiolutherans ” who followed him brought pastors to account, who did not clearly distinguish consecrated from non-consecrated hosts, and partially relieved them of their office. Lutheran churches are also careful with the consecrated wine.

Lord's Supper in the Reformed Churches

Churches that follow the teachings of Huldrych Zwingli and John Calvin believe that bread and wine are signs of Christ's body and blood. When Jesus says: “This is my body”, then this is to be understood as meaning , according to Zwingli (1484–1531). The Lord's Supper is considered a pure memorial meal to commemorate the sacrificial death of Christ. According to Jn 6:63 LUT, for Zwingli the flesh is “useless”, it cannot nourish our spirit. Rather, God acts as a spirit in the spirit of man. The idea of transubstantiation is therefore a delusion for him. For Calvin too, bread and wine at the Lord's Supper are merely “signs and testimonies” of the presence of Christ, who we can only find bodily in “on high”, in heaven. He is at home there alone. There is therefore no point in looking for him here on earth in the bread and wine. The heavenly body of Christ can only be experienced through faith in him and through the bond of the Holy Spirit.

According to the Reformed rite, part of the Lord's Supper is that the Lord's Supper is received by everyone “under both forms” (bread and wine). The liturgy, which is not precisely defined for all cases, includes a sacrament prayer, a thanksgiving prayer and the words of institution (mostly according to 1 Cor 11 : 23-26 LUT ).

Pastors and elders can hand bread and goblets into the rows of seats, where the recipients pass them on to their neighbors: This emphasizes the common priesthood of all believers. The participants can also come to a sacrament table, where pastors and elders hand them the elements: This emphasizes the invitation to the sacrament through Jesus Christ.

The Reformed, as well as many Protestant free churches, do not refer to the Lord's Supper table as an altar and refuse to celebrate the Lord's Supper at the altar, as they set themselves apart from the Roman Catholic understanding of the Lord's Supper as a bloodless sacrifice. They refer to the expression "table of the Lord" ( 1 Cor 10,21 LUT ) and emphasize the uniqueness of the sacrifice of Jesus on the cross of Golgotha .

That is why they almost always use an ordinary wooden table, only in some churches of the Reformation period there are artistically designed marble or stone tables. At church services without the Lord's Supper, there is often an open Bible and a flower arrangement on it, but very rarely there are lit candles.

In Switzerland, many reformed regional churches have given up wine at the Lord's Supper due to the influence of the Blue Cross and instead use grape juice.

Communion with Anabaptist groups

Also Anabaptist groups such as the Mennonites , Amish and Hutterites celebrate the Lord's Supper according to the Reformed understanding as a memorial. Bread and wine are primarily signs and symbols to commemorate the sacrificial death of Jesus Christ. The idea of transubstantiation is rejected.

The Schleitheim articles of the early Anabaptists already speak of the “memory of the shed blood of Christ”. It is also stated that the Lord's Supper should only be celebrated together by those who, through the baptism of faith, belong to the church of God. The Schleitheim articles speak of breaking bread instead of the Lord's Supper , as it is already called in the New Testament. The Dordrecht Confession of 1632, which is still recognized today by Amish and traditional Mennonites, also connects the celebration of breaking bread or the Lord's Supper with the call to charity . The celebration is intended to remind the congregation of the sacrifice of Jesus Christ and to make communion with Christ and with one another clear. Even Menno Simons speaks of the commemorative sign of the mercy of Christ.

Bread and wine can be distributed in Anabaptist congregations by all congregation members (preachers and lay people ). Mostly they are passed on from neighbor to neighbor. There is no mediating authority in the person of a priest or bishop. Instead of an altar, most Mennonite churches speak of a communion table. The Lord's Supper is understood by the Mennonite side as a covenant and not as a sacrament. This is where Anabaptist-Mennonite theology differs from many other Protestant churches and free churches .

In traditional Anabaptist groups, a closed Lord's Supper is practiced and is only celebrated once or twice a year.

Communion with the Baptists

The Baptists celebrate the Lord's Supper as they assume that the early Christians celebrated it: as a reminder of the “all-sufficient” sacrifice of Jesus on the cross at the “table of the Lord”. They emphasize the communal character of the Lord's Supper even more than the Reformed:

From the Baptist point of view, a special or mediating priesthood contradicts the character of the Lord's Supper, through which Jesus Christ alone united all Christians as siblings with equal rights. Therefore, the participants either gather around the Lord's Supper table, around which there are often seats: The deacons (parishioners who take care of the meal and the distribution) or the participants of the Lord's Supper take their places in small groups. Or the participants stay in their seats and the deacons bring them bread and a chalice, which they pass on to one another - often combined with a word of blessing. Those who do not want to take part let the bread and cup pass by.

Methodists

The Methodist Church, which comes from the Anglican and Calvinist tradition, proceeds from the real, personal and living presence of Jesus Christ in the Lord's Supper, without wanting to explain it fully. The doctrine of transubstantiation is rejected. The Lord's Supper is a sacrament, Eucharist (thanksgiving), communion of the Church, remembrance and a means of grace. It is also a sacrifice, but not as a repetition of Christ's sacrifice, but as a “re-representation”, whereby the church presents itself as a sacrifice in unity with Christ ( Rom. 12.1 LUT ).

For Methodists, the Lord's Supper is a celebration of the whole Church - all Christians are welcome, including those who are unbaptized, who want to partake in faith. Nobody may be rejected because of age or lack of understanding. The Lord's Supper is a liturgical celebration presided over by a clergyman. The Methodist Church was an active part of the abstinence movement in the 19th century and, as a result of this tradition, uses grape juice rather than wine.

The hymn book of the Evangelical Methodist Church (edition 2002) knows four different orders of the Lord's Supper. The first form is based on the liturgy of the United Methodist Church , the second and third come from German-speaking conferences, the fourth is a new draft from 2002. A liturgical celebration for the renewal of the covenant with God can be combined with the celebration of the Lord's Supper; it represents a greatly expanded form of the confession of sin.

Breaking bread in the brethren

The Brethren celebrate the Lord's Supper, known as the breaking of bread , as a commemorative meal and understand bread and wine as "signs of God's love".

The congregation gathers in silence around the sacrament table, on which is bread and wine. There is no fixed liturgy, the Holy Spirit should shape the celebration. In the opinion of the Brethren, it moves various members of the community to help shape the celebration. For example, in an unspecified order, Bible texts are read, free prayers are said, songs to be singed together are suggested and sometimes short speeches are given or experiences with God are reported.

As a rule, only those who have been approved by the congregation can take part in the Lord's Supper. In some congregations, outside participants in the Lord's Supper have to show a letter of recommendation from their home church or at least give a credible assurance that they are admitted to the Lord's Supper there.

However, some brother communities now often maintain an “open communion” in which all born again Christians, including those of other denominations, are invited to break bread. Brethren churches usually celebrate the sacrament every Sunday.

The Lord's Supper in the Moravian Church

The Moravian Congregation leaves the middle seat at the Lord's Supper table empty in order to point out the invisible presence of the actual Lord Jesus Christ.

Seventh-day Adventist Understanding of the Lord's Supper

The German Seventh-day Adventists celebrate the Lord's Supper openly and usually only quarterly. In the Reformed tradition, the Lord's Supper is understood as a sign and expression of faith. Preparation includes self-examination, repentance, and confession. Usually unleavened bread and grape juice are served. Before the actual Lord's Supper there is a washing of feet during the service .

Last Supper in the New Apostolic Church

In the New Apostolic Church the Lord's Supper is celebrated in every divine service. For a New Apostolic Christian it is a memory of Jesus' sacrificial death and the closest possible connection with him. After the common prayer of “Our Father”, the acquittal (forgiveness of sins) and the selection of the wafers, the priestly offices present donate the wafers to the worshipers. When handing over the Host, the person who distributes the Lord's Supper speaks the sentence “The body and blood of Jesus have been given for you”, the recipient confirms with “Amen”.

All parishioners and guests are entitled to receive Holy Communion. How one receives the sacrament is much more meaningful. The Lord's Supper is only valid for the recipient if he “enjoys it with dignity” (cf. 1 Cor 11:27 LUT ). To properly enjoy the sacrament, the Church understands that the recipient must:

- be aware of the importance of the sacrifice of Jesus Christ;

- believe that Jesus Christ is present, in particular that Jesus' body and blood should be added to the consecrated hosts ( consubstantiation );

- believe in partaking in the resurrection of Christ. On the one hand, that the soul is thus being prepared to be added to its body, which will one day be resurrected. On the other hand, that one knows Jesus through the breaking of bread and participates in his overcoming of death;

- believe that it imparts powers that help overcome sin and become more like the essence of Jesus.

At divine services of the Chief Apostle and also in divine services of the District Apostle , the “Lord's Supper for the Dead” is held after the general celebration of the Lord's Supper. In a so-called “office crib”, consisting of two officials, two hosts are symbolically given. According to the New Apostolic understanding, the souls who are in eternity and longing for it should receive the sacrament of the Lord's Supper.

Memorial of Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses only celebrate the Lord's Supper once a year, which they also call the “Memorial”. It is their only religious celebration and is very important to them. Wine and bread are understood as symbols. The celebration falls on the 14th day of the month of Nisan on the Jewish calendar. In doing so, they do not follow today's Jewish calendar, but calculate the date - as they believe the Jews at the time of Christ - based on the spring equinox . Days began in the evening after sunset, i.e. the 1st Nisan began when the crescent moon could be seen after the first new moon.

To justify their practice, the Jehovah's Witnesses point out that even in biblical times, important events were only celebrated once a year ( Est 9.21.27 EU ), in particular the miracle of liberation from slavery in Egypt. The Israelites celebrated Passover every year on the exact day they were saved ( Ex 12.24–27 EU ; 13.10 EU ). Immediately after Jesus had finished Passover with his apostles, he introduced the special meal, which would then serve as a model for the celebration of the commemoration of his death ( Lk 22: 7–20 EU ). Since the Passover was celebrated annually, this must also apply to the memorial service that replaced the Passover.

Only a small group of witnesses, who see themselves as called by the Holy Spirit and thus as the earthly remnant of the so-called “144,000” ( Rev 7.4 EU ; 14.1.3 EU ), take from bread and wine; the other witnesses and guests are present as observers of the celebration. During this simple ceremony, the sacrament emblems are handed out by serving ministers of the assembled congregation. Those present remain seated. The symbols are passed on row by row, first the bread, then the wine. There is an opportunity for those who feel called to part with the sacrament emblems. Since only a few thousand of the more than 7 million Jehovah's Witnesses call themselves "spirit anointed", nobody in most communities today takes bread and wine.

Mormon

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints uses water instead of wine because its members do not drink alcohol. The sacrament is the sacred ordinance of which the bread and water are blessed and offered to commemorate the Atonement of Christ.

The sacrament is prepared, blessed, and administered by priesthood holders every Sunday . In preparation, a song is sung to invite the spirit. The sacrament is blessed by reading specified sacrament prayers from the Book of Mormon and Doctrine and Covenants in front of the ward. Then young priesthood holders distribute the bread to the ward. When it is distributed, the water is blessed, consecrated, and distributed. The broken bread represents his body, the water represents the blood he shed to atone for our sins ( 1 Cor 11 : 23-25 EU ; Doctrine and Covenants (D&C) 27 : 2 ).

When worthy members of the Church partake of the sacrament, they promise to take upon them the name of Christ, to remember him always, and to keep His commandments. Through this ordinance, Mormons also renew their baptismal covenants.

See also

literature

New Testament exegesis

- Willibald Bösen: The last day of Jesus of Nazareth. Herder, Freiburg / Breisgau 1995 3 , ISBN 3-451-23214-6 .

- Hartmut Gese : The origin of the Lord's Supper. In: On Biblical Theology. Old Testament Lectures . Kaiser, Munich, 1977, ISBN 3-459-01098-3 , pp. 107–127 (on the Old Testament background of the Last Supper).

- Joachim Jeremias : The Lord's Supper . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1967 4 (1935 1 ).

- Hans-Josef Klauck : Lord's meal and Hellenistic cult . Aschendorff, Münster 1998 2 , ISBN 3-402-03637-1 .

- Hermut Löhr: Origin and meaning of the Lord's Supper in earliest Christianity . In the S. (Ed.): Last Supper (= topics of theology 3). UTB / Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3499-7 , pp. 51-94.

- Jens Schröter : The Last Supper. Early Christian interpretations and impulses for the present (= Stuttgarter Bibelstudien 210). Catholic Biblical Works, Stuttgart, 2006, ISBN 3-460-03104-2 .

Patristic

- Vladimir Latinovic: Christology and Communion. Origin and spread of Homoousian Christology . Aschendorff-Verlag, Münster 2018. ISBN 978-3-402-13358-3 .

Roman Catholic Eucharistic Doctrine

- Alexander Gerken: Theology of the Eucharist. Kösel, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-466-20155-1 .

- Hans Bernhard Meyer , with a contribution by Irmgard Pahl : Eucharist. History, theology, pastoral care. To commemorate the 100th birthday of Josef Andreas Jungmann November 16, 1989 (= Church service. Handbook of Liturgical Science, Part 3). Regensburg 1989, ISBN 3-7917-1200-4 .

- Reinhard Meßner : Introduction to liturgical science , Chapter 3: The Eucharist. Schöningh, UTB 2173, Paderborn 2001, ISBN 3-8252-2173-3 .

- Theodor Schneider : We announce your death. Collected studies on the renewed understanding of the Eucharist. Patmos, Düsseldorf 1980, ISBN 3-491-77336-9

- Theodor Schnitzler : What the fair means. Help for co-celebration. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1990, ISBN 3-451-17689-0 .

- Thomas Schumacher : The celebration of the Eucharist. Liturgical processes - historical developments - theological significance. Pneuma, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-942013-00-0 .

- Catechism of the Catholic Church , Rdz 1322–1419: The Sacrament of the Eucharist. R. Oldenbourg, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-486-56636-9 .

Orthodox Eucharistic teaching

- Alexander Schmemann : Eucharist. Sacrament of the Kingdom of God. Johannes Einsiedeln, Freiburg 2005, ISBN 3-89411-388-X .

- Jan Eike Welchering: Eucharist and deification. Introduction to Theosis by Augustine and Gregory of Nyssa. Akademische Verlagsgemeinschaft München, Martin Meidenbauer Verlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-86306-646-8 , 2nd edition: Akademische Verlagsgemeinschaft München, Thomas Martin Verlag, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-86924-129-6 .

Evangelical doctrine of the Lord's Supper in general

- Council of the Evangelical Church in Germany : The Last Supper. A guide to understanding and practicing the Lord's Supper in the Protestant Church. Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 2003, ISBN 3-579-02378-0 ( online resource PDF; 8.9 MB).

Lutheran doctrine of the sacrament

- Jürgen Diestelmann : Usus and Actio - The Holy Communion with Luther and Melanchthon. Pro Business Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-86805-032-5 .

- Jürgen Diestelmann: Actio Sacramentalis. The administration of Holy Communion according to the principles of Martin Luther in the period up to the formula of the Concord . Verlag der Lutherische Buchhandlung Heinrich Harms, Groß Oesingen 1998, ISBN 3-86147-003-9 .

- Jürgen Diestelmann: About the Lutheran Mass. Congregational lectures and papers . Verlag der Lutherische Buchhandlung Heinrich Harms, Groß Oesingen 1998, ISBN 3-86147-006-3 .

- Karl-Hermann Kandler : Christ's body and blood. Studies on the current Lutheran doctrine of the Lord's Supper (= works on the history and theology of Lutheranism, 2). Lutherisches Verlagshaus , Hannover 1982, ISBN 978-3-7859-0484-8 . At the same time he did his habilitation thesis at the University of Leipzig, 1970.

- Hermann Sasse : Church and Lord's Supper. Flacius, 2nd edition, Fürth 1990, ISBN 3-924022-24-0 .

- Ruth Slenczka: The formative effect of the doctrine of the Lord's Supper and the practice of the Lord's Supper in the 16th century. In: European History Online , ed. from the Leibniz Institute for European History (Mainz), 2010 (accessed on June 13, 2012).

- Gunther Wenz : The doctrine of the Lord's Supper and the practice of the Lord's Supper with special consideration of the Lutheran confessional tradition . In: Alexander Völker (Ed.): Eucharist. Contributions to the theology of the "Renewed Agende" . Evangelische Haupt-Bibelgesellschaft, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-7461-0133-6 ; Pp. 7-33.

- Roland Ziegler: The Eucharist prayer in theology and liturgy of the Lutheran churches since the Reformation. The interpretation of the Lord's Supper between the Promissio and the Eucharist (= Oberurseler Hefte, supplementary volume 12). Edition Ruprecht , Göttingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-8469-0114-4 .

Reformed and United Communion Doctrine

- Thomas Kaufmann : The communion theology of the Strasbourg reformers until 1528 . Mohr Siebeck Verlag, Tübingen 1992, ISBN 3-16-145817-6 .

- Michael Welker : What's going on at the Lord's Supper? Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 2nd edition, Gütersloh 2004, ISBN 3-579-06406-1 .

Free Church doctrine of the Lord's Supper

- Wiard Popkes : Last Supper and Congregation. The Lord's Supper from a biblical-theological perspective and in evangelical-free church practice. Oncken, Kassel 2006, ISBN 3-87939-070-3 .

- Alfred Kuen: The Lord's Supper. Edition Wiedenest, Jota, Hammerbrücke 2001, ISBN 3-935707-03-7 .

- Franz Graf-Stuhlhofer : Symbol or Reality? Baptism and communion . Schwengeler, Berneck 1988.

Ecumenical doctrine of the Lord's Supper

- Institute for Ecumenical Research (Tübingen), Center d'Etudes Oecumeniques (Strasbourg), Denominational Institute (Bensheim): Communion in communion is possible. Theses on Eucharistic Hospitality. Lembeck, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-87476-431-1 .

- Eckhard Lessing : Last Supper (= Bensheimer Hefte 72 / Ökumenische Studienhefte 6). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1993, ISBN 3-525-87160-0 .

- Volker Leppin , Dorothea Sattler (Ed.): Together at the Lord's table / Together at the Lord's table. A vote of the Ecumenical Working Group of Protestant and Catholic Theologians / A statement of the Ecumenical Study Group of Protestant and Catholic Theologians. (= Dialogue of the Churches Volume 17) Herder / Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht, Freiburg / Göttingen 2020, ISBN 978-3-451-38647-3 (144 pages) online

Sacrament celebration

- Gert Kelter: God is present. Suggestions for celebrating the Lutheran worship service (Lutheran Contributions, Supplement 5). Verlag der Lutherische Buchhandlung Heinrich Harms, Groß Oesingen 2003, ISBN 3-86147-254-6 .

- Wolfgang Erich Müller, Enno Konukiewitz (Ed.): Last Supper today. Reflections on theological foundations and contemporary design (= religion in public 6). Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-631-38103-4 .

- Erhard Domay (Ed.): Last Supper. Models, reports, suggestions from practice (= worship practice series B). Gütersloher Verlagshaus Mohn, Gütersloh 2004, ISBN 3-579-03122-8 .

Specialist dictionaries

- Åke V. Ström: Last Supper I. The sacred meal in the religions of the world . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 1, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1977, ISBN 3-11-006944-X , pp. 43-47.

- Gerhard Delling : Last Supper II. Early Christian understanding of meal . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 1, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1977, ISBN 3-11-006944-X , pp. 47-58.

- Georg Kretschmar : Last Supper The Understanding of Last Supper in the History of the Christian Churches III / 1. Old church . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 1, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1977, ISBN 3-11-006944-X , pp. 59-89.

- Erwin Iserloh : The Last Supper Understanding the Last Supper in the History of the Christian Churches III / 2. Middle ages . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 1, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1977, ISBN 3-11-006944-X , pp. 89-106.

- Joachim Staedtke , Erwin Iserloh: Last Supper The Understanding of the Last Supper in the History of the Christian Churches III / 3. Reformation time . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 1, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1977, ISBN 3-11-006944-X , pp. 106-131.

- Albrecht Peters : Last Supper Understanding the Last Supper in the history of the Christian churches III / 4. From 1577 to the beginning of the 20th century . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 1, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1977, ISBN 3-11-006944-X , pp. 131-145.

- Ulrich Kühn : Last Supper IV. The Discussion of the Last Supper in contemporary ecumenical theology . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 1, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1977, ISBN 3-11-006944-X , pp. 145-212.

- Gustaf Wingren : Last Supper V. The Last Supper as a table community according to ethical aspects . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 1, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1977, ISBN 3-11-006944-X , pp. 212-229.

- Georg Kretschmar: Last Supper I. Old Church . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 1, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1977, ISBN 3-11-006944-X , pp. 229-278.

- Hans Bernhard Meyer: Last Supper II. Middle Ages . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 1, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1977, ISBN 3-11-006944-X , pp. 278-287.

- Alfred Niebergall : Holy Communion 16th to 19th century . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 1, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1977, ISBN 3-11-006944-X , pp. 287-310.

- Alfred Niebergall: Last Supper 20th Century . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 1, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1977, ISBN 3-11-006944-X , pp. 310–328.

- Hermann Cremer : Last Supper I Scripture Doctrine . In: Realencyklopadie for Protestant Theology and Church (RE). 3. Edition. Volume 1, Hinrichs, Leipzig 1896, pp. 32-38.

- Friedrich Loofs : Last Supper II Church Doctrine . In: Realencyklopadie for Protestant Theology and Church (RE). 3. Edition. Volume 1, Hinrichs, Leipzig 1896, pp. 38-68.

- Georg Rietschel : Last Supper in the churches of the Reformation . In: Realencyklopadie for Protestant Theology and Church (RE). 3. Edition. Volume 1, Hinrichs, Leipzig 1896, pp. 68-76.

- Klaus Lankheit: Eucharist . In: Reallexikon zur Deutschen Kunstgeschichte , Vol. 6, 1969, Col. 154-254.

Web links

- All articles on: Eucharist. Diocese of Münster

- Herbert Frohnhofen: Doctrine of the Sacraments § 6. Eucharist. In: Theology-Systematic. October 1, 2016 (literature on the Eucharist / doctrine of the Lord's Supper).

- Ulrich HJ Körtner : Sense and taste for the infinite. The Lord's Supper from the perspective of a Protestant theologian. In: Christ in the Present . 13/2003, archived from the original on November 11, 2013 (liberal understanding of the Lord's Supper).

- Volker Rahn: Central points of contention in the Evangelical-Catholic understanding of the Lord's Supper. In: ekhn.de . September 14, 2007, archived from the original on November 11, 2013 .

- The celebration of the Eucharist. In: eucharist-online. Institute for the Promotion of Doctrine of the Faith(explanation of developments in the history of the liturgy and theological significance of the ritual elements of the Eucharist).

- John Paul II: Encyclical Ecclesia de Eucharistia. (pdf, 193 kB) Announcements of the Apostolic See 159, April 17, 2003 (“The Church of the Eucharist”).

- John Paul II: Apostolic Exhortation Mane nobiscum Domine. (pdf, 345 kB) Announcements of the Apostolic See 167, October 7, 2004 (“Remain Lord with us”; for the year of the Eucharist 2004/2005).

- Georgy Krylov: Let the children come to me: giving communion to children under seven years of age. In: bogoslov.ru. March 13, 2012, archived from the original on May 28, 2012 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Petr Pokorný , Ulrich Heckel: Introduction to the New Testament. An overview of his literature and theology. Utb, 1st edition 2007, ISBN 3-8252-2798-7 , p. 152 .

- ↑ Apology I, 65-67; see: Adolf Adam : Grundriß Liturgie. Leipzig 1989, ISBN 3-7462-0404-6 ; P. 131.

- ^ Josef Andreas Jungmann : Missarum Sollemnia , Bd. 1; quoted in: Hans Bernhard Meyer : Eucharist. History, theology, pastoral care . In: Church service. Handbook of liturgical science, part 4 . Regensburg 1989, ISBN 3-7917-1200-4 ; P. 168, note 2; see here also p. 520f.

-

^ Matthias Klinghardt: Community meal and meal community. Sociology and liturgy of early Christian meals . Tübingen 1996.

Dennis E. Smith: From Symposium to Eucharist. The Banquet in the Early Christian World. Minneapolis 2003; B. Eckhardt: Meal V (cult meal). In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christianentum 23 (2009), 1012–1105. - ↑ Lukas Bormann: The Last Supper: cultural anthropological, cognitive scientific and ritual scientific perspectives . In: David Hellholm, Dieter Sänger (Ed.): The Eucharist - Its Origins and Contexts . tape I , 2017, p. 697-731 .

- ↑ for further designations see under KKK 1328–1332 .

-

↑ CiC , Can. 924, Missale Romanum , Institutio Generalis, No. 322, Instruction Redemptionis sacramentum . 50.

Exceptions: Joseph Ratzinger / Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith: Letter to the chairman of the German Bishops' Conference about receiving communion by people who, for serious reasons, cannot eat normal bread and normal wine. (pdf; 19 kB) Diocese of Rottenburg-Stuttgart , July 24, 2003, archived from the original on January 31, 2012 ; accessed on August 17, 2019 . - ^ Leo Hirsch: Practical Judaism. An introduction to practical reality for everyone. Vortrupp-Verlag, Berlin, 1935, DNB 57401022X , p. 97.

- ↑ Last Supper. In: Evangelical Church in Germany. Retrieved November 16, 2014 .

- ^ Secretariat of the German Bishops' Conference: Missale Romanum. Editio typica tertia 2002, Basic Order of the Roman Missal. Pre-publication for the German Missing Book, 3rd edition (PDF; 545 kB); Working aids No. 215, Bonn 2007, No. 281, 283.

- ^ Church with children. A working aid. (pdf, 837 kB) Evangelical Church in Austria, October 22, 2002, p. 49 , archived from the original on November 11, 2013 ; accessed on August 23, 2019 .

- ^ Catechism of the New Apostolic Church. 8.2.21 Eligibility to take part in Holy Communion. In: nak.org. Retrieved November 16, 2014 .

- ↑ Episcopal ordinance for the celebration of the Holy Eucharist: 3rd invitation to receive Holy Communion. Bonn, March 15, 1971, Bishop Josef Brinkhues ; Printed in: Working group for public relations in the Catholic Diocese of Old Catholics in Germany (ed.): Church for Christians today - information about the Old Catholic Church. Hoffmann, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-87344-001-6 , p. 202.

- ↑ see CIC Can. 844, §§ 1–4.

- ^ Katholisch.de:Kommunion: Path paved for evangelical partners

- ↑ dbk.de: Press report, February 22, 2018.

- ^ Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity : Guidelines for Admission to the Eucharist between the Chaldean Church and the Assyrian Church of the East , accessed February 10, 2007.

- ^ Letter from the Prefect of the Roman Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Josef Cardinal Ratzinger, to the Protestant Bavarian regional bishop, 1993.

- ↑ Franziska Hein: What common communion means for mixed confessional couples: "Divorce at the Lord's table". In: kathisch.de . August 26, 2019. Retrieved August 26, 2019 .

- ↑ Marx makes it clear: Ecumenical church convention without communion. In: kath.net. December 11, 2009, accessed November 16, 2014 .

- ↑ quoted from Berthold Altaner , Patrologie , p. 70.

- ^ Translation in: Jan Eike Welchering: Eucharist and Deification. Introduction to Theosis by Augustinus and Gregor von Nyssa , Munich 2011 (Pons Theologiae; Volume 2), p. 39f.

- ^ Odo Casel OSB: Type and meaning of the oldest Christian Easter celebration. In: Yearbook for liturgical science. 14/1934, pp. 1-78, here pp. 46, 48; Second Vatican Council : Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium No. 2.

- ^ DH 1743.

- ↑ II, 4, 70.

- ^ DH 1751.

- ↑ cf. Augsburg Confession Article 13 .