Ibn Battūta

Abū ʿAbdallāh Muhammad Ibn Battūta ( Arabic أبو عبد الله محمد بن بطوطة, DMG Abū ʿAbdallāh Muḥammad Ibn Baṭṭūṭa , Zentralatlas-Tamazight ⵉⴱⵏ ⴱⴰⵟⵟⵓⵟⴰ ) (born February 24, 1304 in Tangier , Morocco; died 1368 or 1377 in Morocco ) was a Muslim legal scholar and author of the supposedly autobiographical travelogue تحفة النظار في غرائب الأمصار وعجائب الأسفار( Tuḥfat an-Nuẓẓār fī Gharāʾib al-Amṣār wa ʿAjāʾib al-Asfār ; German "Gift for those who contemplate the wonders of cities and the magic of travel"; in short: Rihla /رحلة / riḥla / ' journey '). Battūta's travelogue is about a pilgrimage to Mecca and a subsequent journey of more than 120,000 km through the entire Islamic world and beyond.

Life

Pilgrimage to Mecca

At the age of 21 Battūta went on a Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca . He traveled by land along the North African coast until he reached Cairo via Alexandria . Here he was in relatively safe Mamluk territory and set off on his first detour. Back then there were three common stages: a trip up the Nile , then east to the port city of Aidhab on the Red Sea . However, there he had to turn back because of a local uprising.

Back in Cairo, he made a second detour to Damascus (also under Mamluk control at the time) after having met a “holy man” who had prophesied that he would only reach Mecca after a trip through Syria . Another benefit of his detour was that other holy sites lay along the way - such as Hebron , Jerusalem, and Bethlehem - and the Mamluk authorities made special efforts to secure this pilgrimage.

After spending the fasting month of Ramadan in Damascus, Ibn Battuta joined a caravan that covered the route from Damascus to Medina , the burial place of the Prophet Mohammed . In order to keep his strength, Battuta ate the young of his camel, since he could not need offspring. After four days there, he traveled on to Mecca. He completed the rituals necessary to achieve his new status as a hajji and now had his way home before him. After a brief consideration, however, he decided to move on. His next travel destination was the empire of the Mongolian Ilkhan , which is in what is now Iran / Iraq .

Via Mesopotamia to the Silk Road

He again joined a caravan and crossed the border to Mesopotamia , where he visited Najaf , the burial place of the fourth caliph Ali . From here he traveled to Basra , then to Isfahan , which was to be almost completely destroyed only a few decades later by the Turkmen conqueror Timur . Ibn Battuta's next stops were at Shiraz and Baghdad , which was in poor condition after it had been taken by Huegu .

There he met Abu Sa'id , the last ruler of the unified Il Khanate. Ibn Battuta traveled with the royal caravan for a while and then turned north to Tabriz on the Silk Road . As the first major city in the region, Tabriz had opened its gates to the Mongols and had developed into an important trading center after almost all of its neighboring cities had been destroyed.

Along the African coast

After this trip, Ibn Battuta returned to Mecca with a second Hajj and lived there for a year before embarking on a second great journey, this time down the Red Sea along the East African coast. His first big stop was Aden , where he planned to make a fortune trading goods coming from the Indian Ocean to the Arabian Peninsula. Before putting these plans into practice, he decided to embark on one final adventure, and in the spring of 1331 volunteered for a trip south along the African coast.

He spent around a week each in Ethiopia , Mogadishu , Mombasa , Zanzibar and Kilwa, among others . With the change of the monsoon wind , his ship returned to southern Arabia. After making this last trip before settling down for good, he decided to visit Oman and the Strait of Hormuz directly .

From Mecca via Constantinople to Delhi

Then he traveled again to Mecca, where he spent another year and then decided to seek employment with the Muslim Sultan of Delhi . To find a guide and translator for his trip, he went to Anatolia , which was under the control of the Seljuk Turks, and there he joined a caravan to India . A sea voyage from Damascus on a Genoese ship brought him to Alanya on the south coast of what is now Turkey. From there he traveled overland to Konya and Sinope on the Black Sea coast .

He crossed the Black Sea and went ashore in Kaffa in the Crimea , with which he entered the territory of the Golden Horde . While driving through the country, he happened upon the caravan of Özbeg , the khan of the Golden Horde, and joined his journey, which led on the Volga to Astrakhan . Arriving in Astrakhan, the Khan allowed one of his wives, who was pregnant, to have her child in her hometown - Constantinople . It is not surprising that Ibn Battuta persuaded the Khan to let him take part in this journey - the first to take him beyond the borders of the Islamic world.

Towards the end of 1332 he arrived in Constantinople, met the ruler Andronikos III. and saw the Hagia Sophia from the outside. After a month in the city, he returned to Astrakhan, from there to travel beyond the Caspian and Aral Seas to Bukhara and Samarkand . From there he turned south to Afghanistan to cross the mountain passes to India .

In the Sultanate of Delhi

The Delhi Sultanate had only recently become Islamic, and the Sultan wanted to hire as many Islamic scholars and officials as possible to strengthen his power. Because of Ibn Battuta's time as a student in Mecca, he was employed as Qādī (“judge”) by Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq .

The Sultan was unpredictable even by the standards of the day; Ibn Battuta's role fluctuated between the luxurious life of a confidante of the ruler and all sorts of suspicions and suspicions. Finally, he decided to leave the country on the pretext of another pilgrimage. As an alternative, however, the Sultan offered him to become ambassador to China. Ibn Battuta seized the double opportunity both to get out of the reach of the sultan and to travel to new lands.

Via the Maldives to China

On the way to the coast, his tour group was attacked by Hindu barks - he was separated from his companions, robbed and almost killed. Despite everything, he caught up with his group after two days and continued his journey to Cambay . From there he sailed to Calicut in southwest India . While Ibn Battuta was visiting a mosque on the bank, a storm broke and two of his expedition ships sank. The third ship left him on the bank; it was seized a few months later by a regional king in Sumatra .

Afraid of returning to Delhi as a failure , he stayed for a while in the south under the protection of Jamal al-Din . When he had enjoyed his hospitality long enough, it became necessary to leave India for good. He decided to continue his journey to the Empire of China , albeit at the beginning with a detour via the Maldives .

He stayed on the archipelago much longer than intended, namely nine months. His judge experiences were most welcomed in these remote islands and he was forced to stay, half by bribery, half by force. His appointment as chief judge and his marriage into the royal family embroiled him in local politics; when he passed some stern judgments that were not accepted in the liberal island society, he finally had to leave the country again. He turned to Ceylon to visit the religious sanctuary of Sri Pada (Adam's Peak).

When he set sail from Ceylon, his ship almost sank in a storm - after another ship rescued him, it was attacked by pirates. Stranded on the shore, Ibn Battuta made his way to Calicut again, from where he sailed again to the Maldives, before trying again to get to China on board a Chinese junk .

This time the attempt was successful - it quickly reached Chittagong , Sumatra , Vietnam and finally Quanzhou in Fujian Province . From there he turned north towards Hangzhou , not far from what is now Shanghai . Ibn Battuta also claimed to have traveled even further north through the Great Canal (Da Yunhe) to Beijing, but this is generally considered an invention.

Back to Mecca and the Black Death

On his return to Quanzhou, Ibn Battuta decided to return home - although he wasn't quite sure where his home was. Back in Calicut, India, he briefly considered surrendering to the mercy of Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq , but changed his mind and returned to Mecca. On his way through Hormuz and the Il-Khanat he found the Mongol state in the process of dissolution due to a civil war; the ruler Abu Sa'id had since died.

When he arrived in Damascus in order to make his first pilgrimage to Mecca from there, he learned of his father's death. Death remained his companion that year because the plague had broken out and Ibn Battuta witnessed the spread of the black death across Syria , Palestine and Arabia . After reaching Mecca, he decided to return to Morocco, almost a quarter of a century after leaving there. On the way home, he made a last detour via Sardinia and then returned to Tangier - to find out there that his mother had also died a few months earlier.

From Tangier to Spain and back

But it didn't last long in Tangier either - he made his way to Al-Andalus - Islamic Spain. Alfonso XI of Castile threatened to conquer Gibraltar , and Ibn Battuta left Tangier with a group of Muslims - with the intention of defending the port city. When he got there, Alfonso had fallen victim to the plague, and Gibraltar was no longer threatened; Ibn Battuta continued his journey for pleasure. He traveled through Valencia and reached Granada .

A part of the Islamic world that Ibn Battuta had never explored was Morocco itself. On his return trip from Spain he made a short stay in Marrakech , which had almost died out after the plague epidemic and the capital's move to Fez .

Again he returned to Tangier, and again he traveled on. Two years before Ibn Battuta's first visit to Cairo, the Malian King Mansa Musa had crossed the city on his own Hajj and caused a stir because of its ostentatious wealth - at that time about half of the world's gold supplies came from West Africa. Even if Ibn Battuta's notes do not report this explicitly, the hearsay of these events must have piqued his interest, as he set out for this Islamic kingdom on the other side of the Sahara .

Through the Sahara to Mali and Timbuktu

In autumn 1351 Ibn Battuta left Fez and a week later he reached Sijilmasa , the last Moroccan city on his route. A few months later he was on one of the first winter caravans, and a month later he found himself in the middle of the Sahara in the city of Taghaza . As a center of the salt trade , it was inundated with salt and Malian gold - yet the treeless city did not make a favorable impression on Ibn Battuta. He traveled 500 kilometers further through the worst part of the desert to Oualata , then part of the Mali Empire , now Mauritania.

On his onward journey to the southwest he thought he was on the Nile (in fact it was Niger ) until he came to the capital of the Malian Empire. There he met Mansa Suleyman , who had been king since 1341. Although he was suspicious of his stingy hospitality, Ibn Battuta stayed there for eight months before going down the Niger River to Timbuktu . At that time the city was not yet the size and importance it would become in the next two centuries, and he was soon traveling on. Halfway through his return journey, on the edge of the desert in Takedda near what is now Agadez , he received a message from the Moroccan sultan ordering him to go home. At the end of December 1353 he returned from this last trip to Morocco.

Memories and retirement

At the instigation of the Sultan Abū Inān Fāris , Ibn Battuta dictated his travel experiences to the poet Mohammed Ibn Juzaj (d. 1357), who lavishly embellished Ibn Battuta's simple prose style and provided it with poetic additions. Although some of the places in the resulting work " Rihla " ("Journey / Hike") were obviously the product of his imagination, it is one of the most accurate descriptions of some parts of the world in the 14th century.

After he had published "Rihla", Ibn Battuta lived in his homeland for 22 years until he died in 1368 or 1377.

His book remained unknown for centuries, even in the Islamic world. It was not rediscovered until the 19th century and translated into several European languages. Since then Ibn Battuta has grown in fame and is now a well-known figure of the Orient.

Itinerary

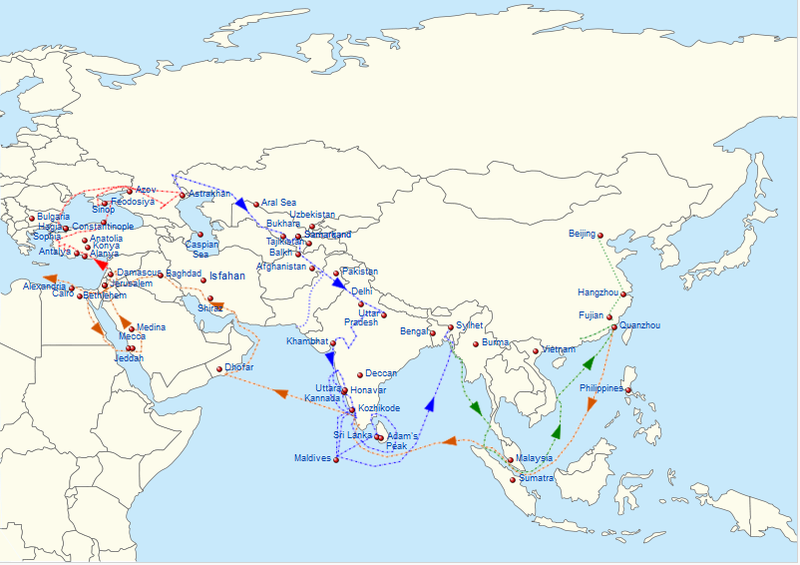

Route 1325-1332

Ibn Battuta itinerary 1325–1332 (North Africa, Iraq, Persia, the Arabian Peninsula, Somalia, Swahili coast) |

Route 1332–1346

Route 1349-1354

Ibn Battuta itinerary 1349-1354 (North Africa, Spain and West Africa) |

Namesake

Ibn Battuta is the namesake for Tangier-Boukhalef Airport , the Ibn Battuta Shopping Mall in Dubai, several ships, including the Ibn Batouta ferry , and the Ibn Battuta lunar crater .

historicity

While Battūta's journey is still considered an important literary work, according to the orientalist Ralf Elger, large parts of the content are to be regarded as fiction or plagiarism of other travelogues. Similar doubts about the historicity of individual contents had already been published by various orientalists and historians.

Writings in English, Slovenian and German translation

- Ibn Batuta: The journey of the Arab Ibn Batuta through India and China (14th century). Modifications made by Hans von Mžik . Hamburg: Gutenberg, 1911 ( Library of memorable journeys . Vol. 5). Digitized

- Ibn Battuta: Travels in Asia and Africa 1325-1354 , translated and selected by HAR Gibb . London 1939 ( The Broadway Travelers ). Digitized

- The Travels of Ibn Battuta AD 1325-1354. HAR Gibb . Translated with revisions and notes from the Arabic text edited by C. Defrémery and BR Sanguinetti . 4 volumes (Volume 4 completed by CF Beckingham ) plus index volume (by ADH Bivar). 1958 ff. ( Works issued by the Hakluyt Society , Second Series 110, 117, 141, 178, 190)

- Ibn Battuta: Journeys to the End of the World 1325-1353. Stuttgart: Edition Erdmann , 1985. ISBN 3-522-60050-9

- The travels of Ibn Battuta. Edited and translated by Horst Jürgen Grün; 2 volumes. Munich: Allitera-Verlag, 2007. ISBN 978-3-86520-229-1 and ISBN 978-3-86520-230-7 (first German translation of the complete work.)

- Ibn Battuta: The wonders of the Orient. Travels through Africa and Asia. Translated into German from the Arabic edition by Muhammad al-Bailuni, with comments and an afterword by Ralf Elger, Munich 2010. ISBN 978-3-406-60068-5 . (Selection of Ibn Battuta's travels by the Syrian scholar al-Bailuni from Aleppo (died 1674))

- Ibn Battuta, Veliko popotovanje / Ibn Battuta; [prevod in uvod Sami Al-Daghistani; soprevajalec Nabil Al-Daghistani]. - Ljubljana: Faculty za družbene vede, Založba FDV, 2016. - Knjižna zbirka SKODELICA KAVE. ISBN 978-961-235-798-6

literature

- Stephan Conermann: The description of India in the "Riḥla" of Ibn-Baṭṭūṭa (= Islamic Studies , Volume 165). Schwarz, Berlin 1993 ( digitized version ).

- Christian R. Lange : The secret name of God. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2008, ISBN 978-3-8053-3841-7 (Ibn Battuta's travel experiences as a template for a historical novel).

- André Miquel: Ibn Battuta: trente années de voyages de Pékin au Niger . In: Charles-André Julien (ed.): Les Africains , Vol. I, Paris 1977, pp. 113-140.

- Erich Follath : Beyond all borders In the footsteps of the great adventurer Ibn Battuta through the world of Islam , DVA, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-421-04690-1

Web links

- Literature by and about Ibn Battūta in the catalog of the German National Library

- Information about Ibn Battuta at www.nationalgeographic.de

- www.welt.de

Remarks

- ↑ The year of death is given differently in medieval Arabic literature as 770 AD (1368 AD) and 779 AD (1377 AD). See JM Cuoq (ed.), Recueil des sources arabes concernant l'Afrique occidentale du VIIIe au XVIe siècle. Paris 1975, p. 289.

- ↑ Tarih ve Medeniyet: Map of Ibn Battuta's travels, 1325 to 1354 (English)

- ↑ Ivan Hrbek , in: Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Lewis Gropp: Contemporary Witness or Forger? In: Deutschlandfunk. August 17, 2010, accessed January 25, 2018 .

- ↑ Roxanne L. Euben: Journeys to the Other Shore: Muslim and Western Travelers in Search of Knowledge . Princeton University Press, 2008, ISBN 9781400827497 , p. 220

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ibn Battūta |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battuta; Ibn Baṭṭuṭa; أبو عبد الله محمد بن بطوطة (Arabic); رحلة (Arabic) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Muslim explorer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 24, 1304 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Tangier , Morocco |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1368 or 1377 |

| Place of death | Morocco |