History of the Jews in Braunschweig

The history of the Jews in Braunschweig began in 1282. After the expulsion in 1546, a Jewish community did not form again in the city until the 18th century. From this emerged in the period up to 1933, among other things, important scholars and entrepreneurs. During the time of National Socialism , at least 196 Braunschweig Jews were victims of the Holocaust . The new Jewish community was established in 1946 and today has around 600 members.

history

middle Ages

|

|

|

|---|---|

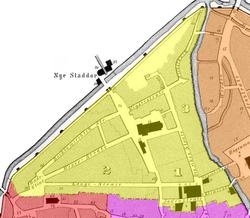

| The Braunschweiger Neustadt (shown in yellow) around 1400. The “Jodenstrate” is on the lower right of the picture. |

The first Jew in the city of Braunschweig is documented for the year 1282. From 1296 Jews were under the protection of Duke Albrecht , for which they paid protection money. In 1320 22 house interest-paying Jewish families, a Jewish school and a meat scraping in are Jodhen strate , today Jöddenstrasse in the precincts of Neustadt , next to the Town Hall mentioned in documents. The origin of these families can be deduced from the names: Helmstedt, Magdeburg, Goslar, Hildesheim, Prenzlau, Stendal and Meißen. Each family paid the Neustadt council an interest for the rented apartments. On May 15, 1345, Duke Magnus granted the Jew Jordan von Helmstedt and his heirs pacified residence in the city and set their interest payments due at Michaelmas and Easter . In a document dated December 6, 1346, the duke took the Jews under his protection. Jurisdiction was settled on March 23, 1349. In addition to the protection money to the duke or the city, the Jews, as "the emperor and the realm's servants ", also had to make payments to the emperor in the form of the "golden sacrificial penny" or "crown money" (aurum coronarium). King Ruprecht transferred the collection of these funds to the Brunswick dukes in 1403.

The Jews mainly settled in the northern part of the old town and in the new town near the markets, their living quarters being separated from the surrounding town by gates. Their main source of income were money lending and pawn shops, since on the one hand the Christian merchants were subject to the prohibition of interest and on the other hand the Christian guilds did not allow Jews. An example of a nationally active entrepreneur is Israhel von Halle († around 1480) , who comes from Halle and has been active in Braunschweig since the 1450s . He lent money to archbishops, nobles and cities and was under the protection of the Braunschweig Council in litigation matters.

Anti-Judaism in the Middle Ages

In the course of the great plague of 1350 , there were pogroms in Braunschweig against Jews who were supposed to be " well poisoners ". The riots claimed around 100 victims, reducing the Jewish population to 50. Since 1435 it was mandatory to wear a special Jewish costume . Further hostility found its expression in allegations in 1437 of an alleged ritual murder , which resulted in the burning of two Jews. In 1510 the Jewish population of Braunschweig was arrested on charges of desecrating the host . They were accused of participating in a crime committed by Jews from the Brandenburg region . While these were victims of a mass burn after a trial in Berlin, the Braunschweig Jews were released and expelled shortly afterwards.

Expulsion 1546

In the city, which had been Lutheran since 1528, several guilds had tried to expel the Jews since 1530. After anti-Jewish attacks in 1543 and 1545, in the course of the Reformation in 1546 the Jews were expelled by the city council of Braunschweig for religious reasons, referring, among other things, to Luther's Jewish writings . After the Protestant city, the Catholic sovereign Duke Heinrich the Younger also issued a deportation ordinance for the surrounding Principality of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel in 1557 after his Guelph cousin Erich II had expelled the Jews from the Principality of Calenberg , which he ruled in 1553 . For economic reasons, however, the Lutheran Duke Julius († 1589), the son of Henry the Younger, escorted the Jews in the summer of 1578 . They then settled in front of the gates of the protesting city in the village of Melverode. As part of a sovereign “ peuplication policy ”, the duke had twelve semi-detached houses built for around 100 people for the wealthy new residents. The first demonstrable Jewish cemetery in Braunschweig was built in 1584 southwest of Melverode. Julius' successor Duke Heinrich Julius († 1613) rescinded the rights and expelled the Jews again on January 6, 1590.

Isolated Jews who stayed in the city and country of Braunschweig until the end of the 17th century did not have any legal protection. This was only granted to them during the Braunschweig trade fairs that take place twice a year . A well-known visitor to these fairs was the Jewish merchant Glückel von Hameln (1646–1724) , who became known through her autobiography .

The Jewish community was reestablished in 1707

The from Halberstadt Dating Alexander David (1687-1765) came to Brunswick in 1707, where he served as chamber Agent under the protection of Duke Anton Ulrich (1714 †) and its successor, August Wilhelm stood († 1731). The newer Jewish community arose around the ducal banker and privileged court Jews . In his residential and commercial building at 16 Kohlmarkt, David had a prayer room, which he had the council approve on the intercession of the pastor of St. Martini . David acquired the neighboring house at Kohlmarkt 12 to later set up a synagogue , which the council did not approve during his lifetime. When he died, the Jewish community of 30 families had neither a synagogue nor its own cemetery. David was buried in his birthplace Halberstadt, where one of the largest Jewish communities in Europe existed at that time. His successor as ducal chamber agent in 1782 was the banker Herz Samson (1738–1794) from Wolfenbüttel , whose grandfather Marcus Gumpel Moses Fulda (1660–1733) founded the Jewish community there. Herz Samson supported Duke Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand († 1806) in averting the impending national bankruptcy through his financial skills . Influenced by the Enlightenment , this ruler, who was known, among other things, to the Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn , lifted outdated discriminatory provisions in his duchy, such as the oath of Jews or the body duty , although full equality was not yet established. During his reign, the Jewish community was able to set up a synagogue in the courtyard of Kohlmarkt 12. In 1797, Duke Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand urged the council to approve the establishment of a Jewish cemetery in the city.

Jewish emancipation in the Kingdom of Westphalia

During the Napoleonic occupation between 1807 and 1813, the former Duchy of Braunschweig-Lüneburg was part of the newly created Kingdom of Westphalia as the " Oker Département " . This was ruled by King Jérôme Bonaparte , a brother of Napoleon Bonaparte . Jews had full citizenship in this kingdom . Jérôme Bonaparte determined in a decree on January 27, 1808 that "... our subjects who are attached to the Mosaic religion [...] should enjoy the same rights and freedoms in our states as our other subjects."

At that time, the Halberstadt-born banker Israel Jacobson (1768–1828), the son-in-law of the ducal chamber agent Herz Samson , had a significant influence on the development of the Jewish communities in the city and state of Braunschweig . The representative of liberal Judaism founded a trading house in Braunschweig, whose citizenship he received in 1804, and worked for the Braunschweig and several other German courts. In 1801, with the ducal approval, he opened a Jewish reform school in Seesen , which from 1805 had non-denominational status. From 1807 to 1813 he was a supplier to the Napoleonic army and financial advisor to King Jérômes, to whom he granted high government bonds. In Kassel , seat of government of the Kingdom of Westphalia, Jacobson worked as president of the consistory of the Israelites . On the one hand, he enforced the legal equality of Jews in the Kingdom of Westphalia and, on the other hand, was at the forefront of an internal Jewish reform movement.

Jacobson's goal was to reform Jewish worship and community life. Based on the Protestant service, this was to be musically accompanied by an organ and the sermon was to be held in German. A confirmation based on the Protestant model should be introduced. Against resistance from conservative Jewish circles, he inaugurated a reform synagogue in Seesen in 1810, where he gave the first sermon as a regional rabbi in the official costume of a Protestant clergyman. After the fall of Napoleon, Jacobson went to Berlin , where he continued to work as a reformer. At Jacobson's suggestion, Samuel Levi Egers (1769–1842), who was again from Halberstadt, was appointed rabbi to Braunschweig in 1809 . He preached in German, but was critical of the reform movements. From 1827 to 1842 Egers was the regional rabbi for the communities of the Duchy of Braunschweig.

Jewish assimilation in the Duchy of Braunschweig

After the end of the Napoleonic occupation in 1813, the legal equality of the Jews in the Duchy of Braunschweig , which was newly founded in 1814, was initially revoked. In 1821 the Jews were granted the right to join guilds and guilds. The general compulsory education for Jewish children was introduced 1827th In the autumn of 1828 a Jewish school was built. In the course of the revolutions of 1830 and 1848 , other rights followed, such as the right to vote and the right to be elected to municipal offices in 1832 . In 1845 the businessman Ludwig Helfft (1793–1867) was elected the first Jewish city councilor. Judeo-Christian mixed marriages were allowed since 1848 . Despite the legal equality achieved in this way, discrimination continued to exist. Jews found practically no employment in the ducal civil service and Jewish lawyers were denied the notary's office , with which the authorization to authenticate legal transactions was connected. For the first time in 1908, the notary's office was granted to the Jewish lawyer Victor Heymann by the regent Johann Albrecht . However, the latter rejected the following request from the Jewish judicial councilor Spanjer-Herford. Occupational discrimination against Jews was abolished in 1919 with the new Reich constitution.

Max Jüdel

The most successful Braunschweig entrepreneur in the period before the First World War was the Jewish merchant Max Jüdel (1845–1910), who in 1873 founded the international railway signal construction company Max Jüdel & Co together with Heinrich Büssing . In 1908 the company, which was absorbed by Siemens 20 years later, had 1,300 employees. Jüdel was president of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, a member of the city council and various technical and social associations and was honored in 1905 with the rarely awarded title of a secret council of commerce . He bequeathed his considerable private fortune to the city of Braunschweig.

Reform Judaism

From 1842 to 1884 Levi Herzfeld (1810–1884) was rabbi of the Braunschweig municipality and from 1843 regional rabbi. He represented a moderate reformist direction. In 1844 the “General German Rabbinical Conference”, which was shaped by Abraham Geiger's reform plans, took place in Braunschweig . The " New Synagogue " was inaugurated in 1875 under Herzfeld's rabbinate . Herzfeld was followed in 1884 by the reform rabbi Gutmann Rülf , who died in 1915. The other Braunschweig regional rabbis were Paul Rieger (1915–1922), Hugo Schiff (1922–1925) and Kurt Wilhelm (1925–1929). From April 1, 1930 to March 31, 1938, Eugen Gärtner (1885–1980) was the last Braunschweig regional rabbi and rabbi of the Braunschweig Jewish community. He emigrated to the USA on April 13, 1938 .

Russian immigration

The proportion of the Jewish population fell from around 1.2 percent at the beginning of the 19th century to 0.5 percent before the First World War. In 1905 the town's Jewish community had 853 members. In the 1903-1906 in Russia angry pogroms several waves of immigration, which increased the number of the Jewish population of Braunschweig together with the existing rural-urban migration by about 200 people followed in time, until 1910. This share of approx. 20 percent “Eastern Jews” was linked in lifestyle and clothing to the culture of the Eastern European “ shtetl ” . A large part of the assimilated Braunschweig Jews who worked as lawyers, university lecturers or businesspeople, among other things, felt that their social integration was endangered by the immigrants. This split was deepened by the “East Jewish Prayer House Bet-Israel” built by the “Eastern Jews” in Echternstrasse .

Time of National Socialism and Holocaust

City and Free State of Braunschweig during the National Socialism

In the elections for the 6th Braunschweig Landtag on September 14, 1930, the NSDAP received 22.16 percent of the vote, making it the third largest parliamentary group after the SPD and the Bürgerliche Einheitsliste (BEL), an association of national conservatives ( DNVP ) and bourgeois conservatives ( DVP , Center Party ) parties and various business associations. As a result of this result, a coalition government of NSDAP and DNVP was formed on October 1, 1930 under Prime Minister Werner Küchenthal (BEL, later NSDAP). Interior minister was initially Anton Franzen (NSDAP), who was replaced a few months later by NSDAP party member Dietrich Klagges due to a scandal . From this point onwards at the latest, pressure and reprisals against the Jewish population grew, the now massive public attacks z. B. was exposed by SA or SS . For this reason, many Braunschweig Jews decided to emigrate before Hitler was appointed Reich Chancellor on January 30, 1933.

Exclusion

In 1933 the Braunschweig Jewish Community had around 950 members. The number of so-called race Jews , which, according to the National Socialist view, also included baptized Jews or atheists , was around 1,150. Just a few weeks after the takeover of power in the German Reich, on March 11, 1933, the city suffered a " warehouse storm " - so-called by Nazi propaganda - which was directed against Jewish shops and staged as a "spontaneous expression of popular anger". SS men in civilian clothes threw numerous shop windows at the Frank , Karstadt , Hamburger & Littauer department stores and destroyed parts of the interior furnishings. This action, organized and directed by SS leader Friedrich Alpers , was to be blamed on “the communists” . In order for the SS to have a free hand for their action, Interior Minister Klagges had instructed the commander of the police in advance to keep police patrols away from the scene, which was what happened. The riots in Braunschweig were followed by similar ones on March 13th in Breslau and on the 15th in Leipzig . On April 1, there was a nationwide boycott of Jewish shops . As a result, Jewish shops, banks and practices were “ Aryanized ” , with their owners being forced to sell to non-Jews, often NSDAP members. The law to restore the civil service of April 7, 1933, excluded most Jews from civil service. In the period that followed, Jewish lawyers, doctors, scientists and artists were also forced out of working life. With the Nuremberg Laws of September 15, 1935, Jews were degraded to people of inferior rights ; marriage between Jews and non-Jews was forbidden (“ Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor ”).

persecution

During the nationwide state terrorism of the November pogroms on November 9 and 10, 1938, anti-Jewish acts of violence occurred in Braunschweig, coordinated by SS leader Friedrich Jeckeln . Troops of the SA and SS destroyed and looted shops, houses and apartments of Jews. The Baron restaurant at Steinstrasse 2, the only kosher restaurant in town, was also destroyed . Five “ stumbling blocks ” that were set in in 2006 are reminiscent of its former owner family . The synagogue was looted and destroyed. Jewish men were arrested and deported to Buchenwald concentration camp to force them to leave the country. Shortly after the pogrom, the Braunschweig Ministry of the Interior reported that 500 of the 1,500 Jews living in the Free State of Braunschweig were still resident there, and of those living in the city, 226 remained. On April 30, 1939, a Reich law abolished the legal protection of tenants for Jews, who as a result often lost their apartments and had to move to one of Braunschweig's “Jewish houses” . The Free State of Braunschweig bought these from Jewish emigrants. They were located at Ferdinandstrasse 9, Meinhardshof 3, Neuer Weg 9, Hennebergstrasse 7, Höhe 3, Hagenbrücke 6/7 and Am Gaußberg 1. Except for two houses, they were destroyed by the bombing.

Deportation and murder

After the beginning of the Second World War , the persecution of the Jews reached a new level, which ultimately aimed at their complete annihilation . Since September 1, 1941, all Jews had to wear a visible yellow star on their clothing; since March 1942, Jewish apartments had to be marked with a “Jewish star ”. Due to the persecution during the Nazi era , the Jewish population of Braunschweig was reduced dramatically from around 1150 in 1933. In 1938 the number had fallen to around 250 as a result of disenfranchisement, persecution and displacement. There is evidence that 196 Braunschweig Jews were deported and murdered in 12 transports to the east. The deportations led on 21 January 1942 to Riga , on 31 March 1942 Warsaw , April 11, 1942 in the East, on July 6, 1942 in the Theresienstadt concentration camp , on 11 July 1942 in the Auschwitz concentration camp , on 24 July 1942 to Theresienstadt, on October 3, 1942 and March 2, 1943 to the East, on March 16, 1943 to Theresienstadt, in May and November 1943 to the East, on November 15, 1944 to the Blankenburg camp and on March 25, 1943 to the East. February 1945 to Theresienstadt. It is assumed, however, that the number of those murdered is considerably higher. Many Braunschweig Jews who were unable to leave or flee for reasons of age or financial reasons chose to commit suicide shortly before their deportation .

Re-establishment of the community after 1945

After the end of the war, some of the few surviving Braunschweig Jews returned to their hometown. At first they were looked after by the district special aid committee for concentration camp inmates. This committee, located at the mayor's office, was founded in 1945 on the instructions of the military government and ensured that the Jews were supplied with essential goods. Reconstruction of the community began in September 1945. Initially, the center was the parish hall, where the rabbi had previously lived. The community later became a member of the regional association of Jewish communities in Bremen and Lower Saxony, which was founded in 1949/1950, and was closely linked to the larger community in Hanover.

It consisted of surviving Braunschweig Jews and those who had moved there. At the beginning of 1953 there were 57 parishioners, in 1969 only 39. The return of the Jewish property stolen in 1938 as a result of the November pogroms was particularly slow in Braunschweig and had to contend with unexpected resistance. Countless lawsuits carried out by survivors or the Jewish Trust Corporation Ltd. (JTC) against the Oberfinanzdirektion and which dragged on until the end of the 50s.

The Jewish community in Braunschweig has been legally independent again since 1983. This year, a new prayer room was built in the Jewish community center on Steinstrasse.

In 2008 the city's Jewish community had almost 600 members. In 1995 Rabbi Bea Wyler took over the spiritual leadership of the parishes in Oldenburg and Braunschweig. This brought the community into the media nationwide, because Wyler was the first rabbi to be hired in Germany after the Holocaust. Jonah Sievers , who comes from Hanover , has been the rabbi of the Jewish community since August 2002 . On December 6, 2006, the new Braunschweig synagogue in Steinstrasse was inaugurated.

There have been contacts between Braunschweig and the Israeli city of Kiryat Tivon since 1968 . In 1981 a friendship agreement was signed and in 1985/1986 it was converted into a town twinning.

Anti-Semitism after 1945

Even after the end of National Socialist rule, there were repeated anti-Semitic crimes in the city. On the night of December 30, 1959 and January 14, 1960, anti-Semitic slogans were written on a memorial and on the walls of houses in Löns Park in the southern part of the city . On January 5, 1960, swastikas and the inscription “Death to the Jews and their helpers” were placed on the bridge there over the Mittelland Canal near Watenbüttel . Three days later, the Franke & Heidecke company staircase was given similar slogans, whereupon the Jewish community filed a criminal complaint with the regional court. However, the perpetrators could not be identified. There were repeated desecrations of graves in the Jewish cemeteries .

Places of remembrance

Jewish cemeteries

The first verifiable Jewish cemetery south of Melverode is documented for 1584. This only existed for a few years and then fell into disrepair. Presumably, however, there was previously a no longer localizable Jewish cemetery within Braunschweig, which had become too small around 1430. For this reason, 23 Braunschweig Jews were buried between 1434 and 1457 in the Hildesheim Jewish cemetery, which was expanded in 1405 . While in the Principality of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel Jewish cemeteries were established in Wolfenbüttel and Holzminden as early as 1724 , in Hehlen in 1740 and in other places in the following years, there was no burial place in Braunschweig until the end of the 18th century. Until then, the Wolfenbüttel Jewish cemetery was preferred by the Braunschweig Jewish Community.

Hamburger Strasse old cemetery

The first Jewish cemetery was laid out before 1782, well before the city limits at that time, in the garden area in front of the Wendentor gate on today's Hamburger Straße . After it soon threatened to become too small, the Jewish community bought an additional plot of land on May 4, 1797 through the mediation of chamber agent Israel Jacobson. Since the establishment of this cemetery, the Chewra Kadischa ( Aramaic for "Holy Brotherhood" ), a special community group, took care of the observance of the Jewish burial regulations according to the " Halacha " . In 1836 this brotherhood was re-established as the “sick and dying association” . The small square burial place was fenced in and locked with a door. In 1801 Jacobson complained about vandalism at the cemetery, so that around 1805 an enclosure wall was built. This cemetery was soon too small again, so that the last burial took place there in 1843. Additional land was acquired on March 20, 1851, creating a total cemetery area of 4,933 m². The new area was used until 1869. In 1853 both parts of the cemetery were enclosed. In the same year a new morgue was built. By 1910 almost all 900 grave sites were occupied, in 1912 only nine grave sites were finally free, so the community had to look for another cemetery. At that time, the design of the new Jewish cemetery on Helmstedter Strasse was already in progress . Up to 1939, 20 more burials, the last on August 3rd of that year, were carried out in the old cemetery. It is noteworthy that, of the Jewish Community regime NS was allowed even at such a late stage of their dead because of a road extension from the old to the new cemetery switch beds . As part of the widening of Hamburger Strasse, 90 graves from around 1900 had to be removed in August of that year. This was done in coordination between the Jewish community and the city of Braunschweig as well as the “ Reich Representation of German Jews ” in Berlin. Since, according to the Jewish rite, the rest of the dead must not be disturbed - i.e. no reburial can be carried out - the Reich Representation wrote on June 14, 1939 to the board of the Jewish community:

“The religious law, according to which the rest of the dead should be ensured as far as possible, must take a back seat to the state legislation. One only has to endeavor in individual cases to do everything possible that can be done for the benefit of our dead. "

In August the 90 grave sites were abandoned , the dead were exhumed and transferred together with the gravestones to Helmstedter Strasse and buried there in a newly created department.

The extent to which the cemetery was desecrated during the Nazi era is unknown. The cemetery was exposed to unprotected destruction in the post-war period due to bomb damage to the surrounding wall and a defective door. In October 1950, the state of Lower Saxony provided funds amounting to 6,000 DM to secure and repair the cemetery. The work ended in August 1951, with not all overturned tombstones having been erected. In 1956 and 1957, gravestones were damaged by young people, whereupon further protective measures were taken in 1958. The graves were again desecrated in 1978. According to an estimate, there are around 930 grave sites in the old cemetery. More than 500 tombstones have been preserved. From 1999 to 2001 the old cemetery was extensively repaired and among other things the mausoleum of the Aschkenasy family was restored.

New Helmstedter Strasse cemetery

In 1887 the new Central Cemetery was inaugurated on Helmstedter Strasse. The city magistrate approached the Catholic and Jewish communities with the suggestion that their burial sites should be connected next to one another. Since the old Jewish cemetery was almost fully occupied, the Jewish community complied with the proposal in 1895 and acquired a neighboring property of 10,124 m² from the Riddagshausen monastery chamber . The immediate vicinity of Christian and Jewish cemeteries was a specialty for the time, as it demonstrated the liberal attitude of the Braunschweig Jewish community as well as the decline in hostility towards Jews in Germany.

"... the excellent location of the new cemetery right next to the Christian ... [is] a sign that prejudices are disappearing and that the barriers that seemed so insurmountable are falling."

Since 1909, the area has been landscaped according to plans by the architect Georg Lübke . He also designed the Jewish cemetery chapel, consecrated in 1914. Even before the cemetery went into operation, an area of 4,473 m² was purchased in 1908, as more and more Jews immigrated from the Russian Empire during this time . In the initial phase, the Jewish community had transferred the management of its cemetery to the main cemetery; only later did it take over this office itself. The first Jewish burial in the new cemetery took place in 1913. From May 1917 this was done regularly. During the Nazi era, the interior of the cemetery chapel was destroyed by the Hitler Youth in 1938 . On March 7, 1941, the Jewish community was forced to sell an area of 9,263 m², which amounted to an expropriation . The area was partly built on or used to build war graves . However, the city did not buy the remaining space.

After the war, on October 6, 1953, a settlement agreement was signed between the city of Braunschweig and the Jewish Trust Corporation (JTC). As a result, "the loss of property of the Braunschweig Jewish Community ... was deemed not to have occurred" . The JTC received the land and sold it, except for the remaining cemetery, directly to the city. The 5,334 m² remaining cemetery was transferred to the small Jewish community of Braunschweig by the JTC on August 12, 1959. This was renovated in 1954/1955, but in the following years it became so vegetated that another renovation had to be carried out in 1978/1979. On November 16, 1958, a memorial stone was unveiled in the Jewish cemetery for the victims of the Jewish community under National Socialist rule. Another plaque commemorates Jewish forced laborers who were deported to Braunschweig in 1941. The looted mourning hall was after the war increasingly fall, but was new again on 11 June 1981, after extensive restoration at the expense of the city of Braunschweig ordained .

Synagogues

In the Middle Ages, the synagogue was on Jöddenstrasse in Neustadt. From 1779 to 1875 the Jewish community owned a synagogue in the back courtyard of the residential and commercial building on Kohlmarkt 12. On September 23, 1875, the new synagogue designed by Constantin Uhde in the Romanesque-oriental style was inaugurated in the Alte Kniehauerstraße. Much of the construction costs were financed from the legacy of the court banker Nathan Nathalion (1805–1864). The synagogue was badly damaged in the so-called Reichskristallnacht from November 9th to 10th, 1938 and demolished in December 1940 due to dilapidation. An air raid shelter , which still exists today, was immediately built on the site . In 1976, a memorial plaque was placed there in memory of the destroyed synagogue. The Jewish community center, which is only a few meters away from the building on Steinstrasse, was reopened in 1983. A memorial plaque was inaugurated there for the Jewish citizens who lost their lives between 1933 and 1945. A new synagogue has existed in Steinstrasse since December 6, 2006 .

Jewish Museum

The Jewish Museum goes back to the Judaica collection of court Jew Alexander David, which was open to the public as early as 1746 . It has been shown in its rooms from 1891 to 1944 since the " Fatherland Museum " was founded. The exhibition was also open to the public during the National Socialist era, although the discrediting inscription “Foreign bodies in German culture” was applied. After the end of the Second World War, the collection could initially not be shown again due to lack of space. It was not until October 27, 1987 that the traditional “Jewish Museum” section of the State Museum was reopened in the Hinter Aegidien exhibition center. The Hornburg Synagogue, built in 1925, is one of the most important exhibits .

"Stumbling blocks"

On March 9, 2006, the first eleven “ Stolpersteine ” in Braunschweig were laid by the sculptor Gunter Demnig in places where Jews lived until 1945. So z. B. on the old town and the Kohlmarkt as well as in the Steinstraße, very close to the new synagogue. The stones are supposed to commemorate the last place of residence of the Braunschweig Jews persecuted by the National Socialists.

literature

- Reinhard Bein : Eternal House - Jewish cemeteries in the city and country of Braunschweig . Döringdruck, Braunschweig 2004, ISBN 3-925268-24-3 .

- Reinhard Bein: Jews in Braunschweig 1900–1945 , 2nd edition, Braunschweig 1988

- Reinhard Bein: life stories of Braunschweiger Jews. döringDruck, Braunschweig 2016, ISBN 978-3-925268-54-0 .

- Reinhard Bein: You lived in Braunschweig. Biographical notes on the Jews buried in Braunschweig (1797 to 1983) , In: Mitteilungen aus dem Stadtarchiv Braunschweig , No. 1, Döring Druck, Braunschweig 2009, ISBN 978-3-925268-30-4

- Reinhard Bein: Zeitzeichen - Stadt und Land Braunschweig 1930–1945 , 2nd edition, Braunschweig 2006

- Reinhard Bein: Contemporary Witnesses from Stein Volume 2 - Braunschweig and his Jews , Braunschweig 1996, ISBN 3-925268-18-9

- Bert Bilzer and Richard Moderhack (eds.): BRUNSVICENSIA JUDAICA. Memorial book for the Jewish fellow citizens of the city of Braunschweig 1933–1945 , in: Braunschweiger Werkstücke , Volume 35, Braunschweig 1966

- Ralf Busch (Red.): To commemorate the former Jewish community of Braunschweig , In: Publications of the Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum , issue 11, Braunschweig 1977

- Hermann Dürre : History of the City of Braunschweig in the Middle Ages , pp. 637–639, Braunschweig 1861

- Hans-Heinrich Ebeling : The Jews in Braunschweig: Legal, social and economic history from the beginnings of the Jewish community to emancipation (1282-1848) , Braunschweig 1987

- Hans-Heinrich Ebeling: Jews , In: Luitgard Camerer , Manfred Garzmann , Wolf-Dieter Schuegraf (Hrsg.): Braunschweiger Stadtlexikon . Joh. Heinr. Meyer Verlag, Braunschweig 1992, ISBN 3-926701-14-5 , p. 119 .

- Jürgen Hodemacher : Braunschweig's streets, their names and their history. Volume 1: City Center , Cremlingen 1995

- Horst-Rüdiger Jarck , Gerhard Schildt (ed.): The Braunschweigische Landesgeschichte. A region looking back over the millennia . 2nd Edition. Appelhans Verlag, Braunschweig 2001, ISBN 3-930292-28-9 .

- Cord Meckseper (Ed.): Stadt im Wandel , exhibition catalog Volume 1, p. 500ff., Stuttgart 1985

- Richard Moderhack : Braunschweiger Stadtgeschichte , Braunschweig 1997

- City of Braunschweig (ed.): When you build a house, you want to stay. The history of the Braunschweig Jewish community after 1945 , Quaestiones Brunsvicenses, reports from the Braunschweig City Archives 15, Braunschweig 2005

- Peter Schulze: With David's shield and menorah. Pictures of Jewish graves in Braunschweig, Peine, Hornburg, Salzgitter and Schöningen. Exhibition 1997–2002 , in: Series of publications Regional Trade Union Sheets, published by DGB-Region SüdOstNiedersachsen, Hanover 2003

- Lorenz Pfeiffer , Henry Wahlig : Jews in Sport during National Socialism. A historical handbook for Lower Saxony and Bremen. Göttingen, 2012

Web links

- Networked Memory - Topography of the National Socialist Tyranny in Braunschweig

- Central Council of Jews in Germany, small but nice: the Braunschweig Jewish community relies on continuity , June 25, 2004

- Stumbling Stone Project Braunschweig

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hans-Heinrich Ebeling in: Camerer, Garzmann, Schuegraf, Pingel (eds.): Braunschweiger Stadtlexikon , Braunschweig 1992, p. 118

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Ludewig : The state of Braunschweig in the Third Reich (1933-1945). In Horst-Rüdiger Jarck, Gerhard Schildt (Hrsg.): Braunschweigische Landesgeschichte. A region looking back over the millennia. Appelhans Verlag, Braunschweig 2000, ISBN 3-930292-28-9 . Pp. 1004-1007.

- ↑ Braunschweig Jewish Community on the website of the Central Council of Jews in Germany

- ^ Hermann Dürre: History of the City of Braunschweig in the Middle Ages, Braunschweig 1861, p. 639

- ↑ Horst-Rüdiger Jarck (Ed.): Braunschweigisches Biographisches Lexikon 8th to 18th Century , Braunschweig 2006, pp. 371–72

- ^ Hans-Jürgen Derda: Zion - a look at the Jewish history in: Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum, Informations undberichte 1/2000 , Braunschweig 2001, p. 12

- ↑ Reinhard Bein: Zeitzeugen aus Stein Volume 2 - Braunschweig und seine Juden , Braunschweig 1996, p. 11

- ↑ Monika Richarz, Reinhard Rürup: Jüdisches Leben auf dem Lande: Studies on German-Jewish History , Tübingen 1997, p. 31

- ↑ Reinhard Bein: Eternal House - Jewish Cemeteries in the City and Country of Braunschweig , Braunschweig 2004, p. 32

- ↑ Horst-Rüdiger Jarck, Günter Scheel (ed.): Braunschweigisches Biographisches Lexikon 19. und 20. Century , Hannover 1996, p. 269

- ↑ Reinhard Bein: Zeitzeugen aus Stein Volume 2 - Braunschweig und seine Juden , Braunschweig 1996, p. 95

- ↑ Bert Bilzer and Richard Moderhack (eds.): Brunsvicensia Judaica , Braunschweig 1966, p. 169

- ^ Result of the election for the 6th Braunschweig Landtag

- ↑ Gerd Biegel (Ed.): Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum - Information and Reports , 2/1999, Braunschweig 1999, p. 13

- ↑ Reinhard Bein: Eternal House - Jüdische Friedhöfe in Stadt und Land Braunschweig , Braunschweig 2004, pp. 69–70 / With Bert Bilzer and Richard Moderhack: BRUNSVICENSIA JUDAICA - Memorial Book for the Jewish Citizens of the City of Braunschweig 1933–1945 , in: Braunschweiger Werkstücke , Volume 35, Braunschweig 1966, p. 152, as the result of the census of June 16, 1933, it is stated that 682 people who professed the Jewish religion lived in Braunschweig.

- ↑ Reinhard Bein: Ewiges Haus - Jewish cemeteries in the city and country of Braunschweig , Braunschweig 2004, pp. 69–70

- ↑ a b Reinhard Bein: Jews in Braunschweig 1900–1945 , 2nd edition, Braunschweig 1988, p. 53

- ↑ Reinhard Bein: Juden in Braunschweig 1900–1945 , 2nd edition, Braunschweig 1988, p. 50

- ↑ Reinhard Bein: Eternal House - Jewish Cemeteries in the City and Country of Braunschweig , Braunschweig 2004, p. 206

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Ludewig: The state of Braunschweig in the Third Reich (1933-1945). In Horst-Rüdiger Jarck, Gerhard Schildt (Hrsg.): Braunschweigische Landesgeschichte. A region looking back over the millennia. Appelhans Verlag, Braunschweig 2000, ISBN 3-930292-28-9 . Pp. 1004-1007.

- ^ Norman-Mathias Pingel: Judenhäuser , in Braunschweiger Stadtlexikon supplementary volume , Braunschweig 1996, p. 74

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Ludewig : The country of Braunschweig in the Third Reich (1933-1945). In Horst-Rüdiger Jarck, Gerhard Schildt (Hrsg.): Braunschweigische Landesgeschichte. Millennial review of a region , Braunschweig 2000, pp. 1004–1007.

- ↑ Reinhard Bein: Zeitzeichen - Stadt und Land Braunschweig 1930–1945 , 2nd edition, Braunschweig 2006, p. 173

- ↑ a b Herbert Obenaus (Ed.): Historical manual of the Jewish communities in Lower Saxony and Bremen. Wallstein, Göttingen 2005. ISBN 3-89244-753-5 , p. 302

- ↑ Reinhard Bein: Eternal House - Jewish Cemeteries in the City and Country of Braunschweig , Braunschweig 2004, p. 26

- ^ Herbert Obenaus (Ed.): Historical manual of the Jewish communities in Lower Saxony and Bremen. Wallstein, Göttingen 2005. ISBN 3-89244-753-5 , p. 303

- ↑ Irina Leytus: Small but nice: the Braunschweig Jewish community relies on continuity

- ↑ Braunschweiger Zeitung of December 7, 2006 Report on the inauguration of the new synagogue

- ↑ City of Braunschweig (ed.): If you build a house, you want to stay. The history of the Braunschweig Jewish community after 1945 , Quaestiones Brunsvicenses, reports from the Braunschweig City Archives 15, Braunschweig 2005, pp. 52–56

- ↑ Peter Aufgebauer: The history of the Jews in the city of Hildesheim in the Middle Ages and in the modern times , Hildesheim 1984, p. 38

- ^ Alfred Haverkamp, Franz-Josef Ziwes: Jews in the Christian environment during the late Middle Ages , Berlin 1992, p. 44

- ↑ a b c d Peter Schulze: With shield of David and menorah. Pictures of Jewish graves in Braunschweig, Peine, Hornburg, Salzgitter and Schöningen. Exhibition 1997–2002 , in: Series of publications Regional Trade Union Sheets published by DGB-Region SüdOstNiedersachsen, Hannover 2003, p. 4

- ↑ Peter Schulze: With shield of David and menorah. Pictures of Jewish graves in Braunschweig, Peine, Hornburg, Salzgitter and Schöningen. Exhibition 1997–2002 , in: Series of publications Regional Trade Union Sheets published by DGB-Region SüdOstNiedersachsen, Hannover 2003, p. 6

- ↑ Reinhard Bein: Eternal House - Jewish Cemeteries in the City and Country of Braunschweig , Braunschweig 2004, p. 55

- ↑ Jewish cemeteries in Lower Saxony - Braunschweig (Helmstedter Straße) in the cemetery documentation collection on the website of the central archive for research into the history of Jews in Germany

- ↑ Peter Schulze: With shield of David and menorah. Pictures of Jewish graves in Braunschweig, Peine, Hornburg, Salzgitter and Schöningen. Exhibition 1997–2002 , in: Series of publications Regional Trade Union Sheets published by DGB-Region SüdOstNiedersachsen, Hannover 2003, p. 9

- ↑ City of Braunschweig (ed.): If you build a house, you want to stay. The history of the Braunschweig Jewish community after 1945 , Quaestiones Brunsvicenses, reports from the Braunschweig City Archives 15, Braunschweig 2005, p. 48

- ↑ Peter Schulze: With shield of David and menorah. Pictures of Jewish graves in Braunschweig, Peine, Hornburg, Salzgitter and Schöningen. Exhibition 1997–2002 , in: Series of publications Regional Trade Union Sheets published by DGB-Region SüdOstNiedersachsen, Hannover 2003, p. 12