Lindau (Eichsfeld)

|

Spots Lindau

Community Katlenburg-Lindau

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Coordinates: 51 ° 39 ′ 17 ″ N , 10 ° 7 ′ 28 ″ E | ||

| Height : | 169 m above sea level NHN | |

| Area : | 9.92 km² | |

| Residents : | 1716 (Jul 1, 2018) | |

| Population density : | 173 inhabitants / km² | |

| Incorporation : | March 1, 1974 | |

| Postal code : | 37191 | |

| Area code : | 05556 | |

|

Location of Flecken Lindau in Lower Saxony |

||

|

Center with catholic church St. Peter and Paul

|

||

Lindau ( ) is an in Südniedersachsen lying spots with around 1,700 inhabitants. It belongs to the municipality of Katlenburg-Lindau and is - the only place in the Northeim district - in the Untereichsfeld . Until 1972, the then independent community of Lindau belonged to the former district of Duderstadt .

Lindau has some historically valuable buildings. In Lindau, for example, there is the famous Mushaus, whose roots go back to the 14th century and which was once part of a medieval castle. The so-called murder mill, which is reported in a legend, can also be described as historically valuable.

geography

location

Lindau is about 10 km southeast of Northeim on the B 247 federal highway . The location extends over the river floodplains of Rhume and Oder at an altitude of approx. 145 m above sea level. NHN . Smaller elevations are in the southwest of the Schornberg (218 m) and in the west of the Lindau Forest (208 m).

Neighboring places

| Wachenhausen | Katlenburg | |

|

Wulften am Harz | |

| Gillersheim | Bilshausen |

history

Lindau was first mentioned in a document in 1184.

Early history of the Lindau district

Only vague statements can be made about the pre-medieval history of today's Lindau, based on a few finds and findings. To this day, research and excavations on a large scale have not taken place.

In the course of the 20th century, some finds were made that indicate an earlier settlement of Lindau. So was z. In 1938, for example, the then mayor Heinrich Leinemann found a very well-preserved arrowhead from prehistoric times in the Lindau schoolyard . However, later research revealed that the approximately 8,000 year old tip must have come from the USA. How she got to Lindau has never been fully clarified. When the canal at the Mushaus was filled in in 1986, a medieval vessel was found, which, however, could not be dated because the site was not explored. Unlike the arrowhead, however, this vessel dates from the Middle Ages .

On the slopes of the Lindau Klingenberg, hand axes and other small tools from the Old and Middle Stone Age can be found. Flint blades could also be found on the Klingenberg and on the Hang Am Brande and in the area of the Mordmühle.

These findings prove that today's Lindau was already settled around 10,000 years ago.

On the other hand, only a few ceramic fragments could be found, which, however , can be dated with caution to the pre-Roman Iron Age (800 BC to the birth of Christ). Despite the adverse conditions during field inspections and the small amount of finds that can be explained with them, it is assumed that this area was rather sparsely populated in pre-Christian times.

In the immediate vicinity of the present-day town of Lindau two now non-existent villages (are deserted villages ) suspects: Meginwardeshusen and Tappen Husen. The first place mentioned is believed to be near the murder mill. The name is first mentioned in a document in 1105. When the place disappeared is not known, but the settlement still existed in 1341. The name of the village changed several times over the years and in 1785 the hallway where this place was supposed to be called Word Mill. This name explains the term “murder mill”.

Tappenhusen was first mentioned in 1504. In this case, too, the end of this place is not known. Where exactly Tappenhusen was located cannot be conclusively clarified; there are no studies here either. Tappenhusen was believed to be about 2 km from Lindau. Either he was between Lindau and Bilshausen or between Lindau and Gieboldehausen .

The location of the old Lindau castle

The new Lindau Castle , of which only the Mushaus still exists today, was built in the 14th century. But even before that, Lindau owned a castle, which today is only reminiscent of a depression east of the Rhumebrücke at the exit to Gillersheim . Based on an aerial photo from 1983, several such observations were made in the region, which were largely followed up. However, Lindau was not included in this research.

A moated castle is believed to be the forerunner of the later castle that existed in the 12th and 13th centuries. Nevertheless, the exact position of the old Lindau castle was always controversial. This won't change until an excavation is made. Nevertheless, the lowering visible on the aerial photo is the most likely place for the old castle, especially the good traffic situation speaks for it.

Opposite this area, the name "Burgwall", which is common for the area, still reminds of the disappeared castle.

The following lords of the new castle are proven in Lindau:

- 1322 Ludolf von Wedeheim and Burkhard von Wittenstein

- 1338 Conrad von Rosdorf, Jan von Hardenberg

- afterwards that of Tastungen, of Bortfeld

- a castle loan behind the must-do house to the Lords of Uslar and from these in 1453 to Heinrich von Bodenhausen

- a loan from Revenfloh in 1383 to Albrecht von Leuthorst

- around 1530 Heinrich and Caspar von Hardenberg

- and around 1577 Dietrich and Heinrich von Hardenberg

Lindau during the Reformation up to the Seven Years War

During the Reformation , Lindau was subordinate to the Elector and Archbishop of Mainz . This meant that the people of Lindau were of the Catholic faith. After the Reformation, however, this was to change temporarily under the influence of the Hardenberg noble family. In 1558 the majority of the population had become Protestant.

However, the Elector of Mainz initiated the Counter-Reformation between 1574 and 1582, which was, however, not very successful. Ultimately, the neighboring Guelph areas also played a role, as they remained Protestant and thus also influenced Lindau. Protestantism still predominated in Lindau at the beginning of the 17th century. Only when repressive measures had been introduced against the remaining Protestants did the place gradually return to Catholicism.

The next few years went smoothly for Lindau. This changed with the beginning of the Thirty Years War (1618–1648). The first years of the war had not yet reached Lindau, but the citizens lived in fear and horror from reports from already devastated villages.

Large parts of the Eichsfeld were destroyed under the leadership of Duke Christian (called: "the Tolle") of Braunschweig. Lindau was destroyed on April 25, 1626, even the church had been devastated, so that it could only be rebuilt in a makeshift manner and was demolished in 1758 and replaced by today's St. Peter and Paul. Only the Mushaus survived the destruction. The following years put the people of Lindau to severe tests. When the plague finally broke out, Lindau was almost completely at an end.

During the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), Lindau was spared renewed destruction. Nevertheless, this war also meant the Lindau years of suffering and privation.

Lindau under Electoral Mainz rule (1521–1802)

Together with the Eichsfeld, Lindau had been under the rule of the Archdiocese of Mainz since 1521. Since the Hardenberg nobility had had a very high influence in Lindau for a long time, the archbishopric did not appoint any members of the Hardenbergers as officials. The political influence could thus be pushed back.

Over the years there was a dispute with the Diocese of Hildesheim , which Lindau had initially only pledged to Mainz. However, through clever negotiations, Mainz always managed to keep Lindau in its sphere of influence. For example, in 1785 the Hildesheim diocese tried again and again to detach Lindau from the union with Mainz, with the reference to the fact that Lindau was only pledged.

The size of the office of Lindau has varied again and again due to its peripheral location to different domains. Only Lindau and Bilshausen always formed the Lindau office, while other localities (e.g. Berka , Bodensee , Krebeck , Renshausen and Thiershausen ) only belonged to this office temporarily. Since the 17th century, however, the size of the office decreased and in 1692 Mainz completely canceled its claims about Berka after there had been arguments between various powers over this place. In 1782, the Lindau office only consisted of Lindau and Bilshausen.

In the 18th century there were only very few villages in Lindau. Since Kurmainz could never be sure how long Lindau could hold it in his possession, it can be assumed that the size of the Lindau office was deliberately kept small. The following magistrates are known:

- 1500 Johann von Minnigerode

- 1545–1549 Kaspar von Hardenberg

- 1549–1579 Nikolaus von Lenthorst

- 1589 Hans Voss

- 1617–1635 Johannes Grobecker

- 1656–1685 Jodocus Adrian Schott

- 1685–1722 Johann Andreas Schott

- 1748–1756 Georg Karl Klinckhardt

- 1791 Heinrich Schuchardt

(Source:)

Lindau under the first rule of Prussia (1802–1806)

Like the whole of Eichsfeld, Lindau was connected to the Archdiocese of Mainz in many ways. As Archbishop of Mainz and Arch Chancellor of the German Empire at the same time , Eichsfeld was involved in many European wars. Kurmainz did not survive the participation of the Electorate of Mainz in the wars to suppress the French Revolution . Thus the entire Eichsfeld was taken over by Prussia in 1802, before the Treaty of Luneville .

The people of Lindau were anything but satisfied with the new rule and soon wished for the old rule to be restored. Massive tax burdens and the planned - but never completed - dissolution of the Lindau office did not contribute to a friendly climate against Prussia.

The first epoch of Prussian rule, however, was to be short-lived. Prussia was defeated in October 1806 in the battle of Jena and Auerstedt . The Eichsfeld now came into French possession.

Lindau as part of the Kingdom of Westphalia (1807–1813)

In 1807, the French Emperor Napoléon I founded the Kingdom of Westphalia . Napoléon appointed his younger brother, Hieronymus Bonaparte , as king . The kingdom ruled by King Hieronymus included the Eichsfeld and u. a. Hessian , Brunswick and other areas.

The new kingdom was divided according to the French model. And so the Eichsfeld (thus also Lindau) was assigned to the department of the Harz Mountains and Lindau as the only place in the Eichsfeld was assigned to the Osterode district . Within this district, Lindau, along with Wulften , Berka, Hattorf and Dorste, represented the canton of Lindau. As can quickly be seen, this administrative reform did not take any account of denominational affiliations. The new administration was an extremely modern and efficient facility for the time.

On an order from Napoleon , all areas under his control had to move their cemeteries to the outside, as there was fear of contamination of the groundwater. Therefore, the cemetery, which was initially located at the Catholic Church, was moved to its current location on the main road. The new cemetery was consecrated in 1820.

The Napoleonic Wars , in which the Kingdom of Westphalia took part, let it bleed to death and also brought famine for Lindau. In spring 1813 a Prussian volunteer corps succeeded in driving the Westphalian troops out of Eichsfeld. The Eichsfelder immediately joined the Prussian troops to drive the hated French occupiers out of their area. When the Napoleonic armies were defeated in the Battle of Leipzig , Lindau and the Eichsfeld had already freed themselves.

What now followed was a second, but this time very short, epoch under Prussian rule. The displeasure quickly turned against Prussia again. Like the rest of the Prussian territories, Lindau had to deliver vast quantities of materials and natural produce and, like the rest of the Eichsfeld, was obliged to provide a very large contingent of soldiers. Ultimately, this left almost exclusively children and the elderly.

It wasn't until the Congress of Vienna that better times would break for Lindau.

From the Congress of Vienna to the First World War (1815-1918)

29 villages in the lower area became part of the Kingdom of Hanover , including Lindau, which lost its importance in the course of administrative reforms. The old Lindau office was not restored, instead a Gieboldehausen-Lindau office, which Gieboldehausen had as its administrative seat. In 1832 the Katlenburg office was finally merged with the former Lindau office to form the new Catlenburg-Lindau office.

During the March Revolution of 1848, young people with black, red and gold flags marched through the town in Lindau to demand equality and freedom. There should have been riots.

A judicial reform in the Kingdom of Hanover resulted in Lindau being given a district court in 1852 , which, however, like the entire office, was dissolved again in the second Hanoverian administrative reform in 1859. Great damage had been done to the village. The now inoperable Lindau administrative building was acquired as a residence by the Lindau industrialist August Greve in 1872 for 10,000 thalers .

After the German war between Austria and Prussia in 1866, the second epoch of Prussian rule over Lindau began. The Lindau people were in opposition to Prussia and showed this in elections.

In a renewed administrative reform, Lindau came to the newly created district of Duderstadt with Duderstadt as the administrative seat. In the course of the 19th century the city lost importance compared to the economically flourishing Northeim .

On the afternoon of April 15, 1911 - a Holy Saturday - there was the largest and most devastating fire in Lindau to date. Two boys had made a fire in the farm of the farmer Heinrich Freyberg (in Unterflecken). As it was very windy, the fire quickly spread to the buildings of the master mason Linnekuhl and the Ackermann Freyberg. Because of the primitive extinguishing devices and the lack of extinguishing water (the room is far away), the place quickly caught fire. 42 houses and around 30 outbuildings burned down completely as a result of the fire. Many houses were not rebuilt after the fire. The Mariendenkmal, which still exists today, was erected on the spot where the Lombard and Behr families used to be.

In response to this fire, the Lindau volunteer fire brigade was founded in the same year. In the 19th century, Lindau's economic importance increased with the settlement of the jute spinning mill in Greve (1872) and the production of brewery pitch.

Political Conditions during the Weimar Republic (1918–1933)

Since the 17th century, Lindau consisted mainly of Catholics again. According to a census from 1934, there were 1,487 inhabitants, of which 85.5% were Catholic and only 14.5% were Protestant. At that time there were no longer any Jewish residents in Lindau. This also influenced the voting behavior of the Lindau population during the Weimar Republic . Since there was a Catholic party with the center , this party had a special supremacy in Lindau, which could also be observed in other places in Eichsfeld.

In 1920 the Center Party won 69.8% of the votes cast in the Reichstag election. Despite all this, this value was even lower than in other municipalities in Duderstadt. Compared to Duderstadt itself, however, it was higher. The center was able to maintain this high share of votes throughout the first German republic and in 1932, in the last free elections, this party was still able to win 60.8% of the votes, while in many places the NSDAP had long since become the strongest political force .

While the SPD got 10% of the votes cast in the Reichstag elections of 1920, the much more socialist USPD surprisingly managed to get 11.4%. In no other rural community around Duderstadt was there a higher proportion of left-wing voters at the time. Contemporary witnesses attributed this to the large number of workers at the local Greve jute mill. It is possible that the neighboring communities of Wachenhausen and Gillersheim , in which the SPD has had a fairly high level of influence since then and received the most votes, may also be influenced. The workforce there was also very well organized.

However, after the KPD was founded and the USPD dissolved, the extreme left no longer played a role in the elections in Lindau. In the elections of 1928, the SPD had an unusually loyal electorate, at over 16%, for Eichsfeld, so that in 1932 the SPD still received 13% of the vote.

The influence of the non-Catholic bourgeois parties was less than that of the Social Democrats, but it was still worth mentioning for a town in Eichsfeld. In 1920 the DVP received around 8% of the vote. But it could not maintain this high value because it gradually shrank to insignificance. The DHP had now taken its place and received 8.7% of the vote in 1924 and 10.7% in 1928. The fact that this party was so successful is astonishing for Eichsfeld, but can probably be explained again by the influence of the predominantly Protestant neighboring communities in which the DHP was an important political force.

The national right in Lindau elected the German National People's Party (DNVP), which received 5.8% of the vote for the first time in May 1924, but only 2% in 1928. In Lindau, the nationally-minded bourgeoisie formed in the Young German Order , which was particularly strongly criticized by center politicians because parts of the Jungdo (the short form) were hostile to Catholicism .

The influence of the National Socialists in Lindau was always minimal. In 1928 the center, the SPD and the DHP received the decisive share of the vote. And these parties supported the republic. The National Socialists appearing in Lindau for the first time this year received a total of two votes (0.3%) and initially remained meaningless in the following years. Because even in the Reichstag elections in November 1932, the center (60.8%) and the SPD (12.9%) still united 73.7% for themselves and thus for the democracy supporters. The DHP had sunk into insignificance. This value shows that, unlike in the surrounding towns, the Democrats still had the upper hand in Lindau. This circumstance can probably be traced back to the decided distancing of the Catholic Church from National Socialism.

But in November 1932 a certain importance of the Nazis could no longer be overlooked here either. The NSDAP made it to 21.9% and became the second strongest force in Lindau behind the center. In addition, a local branch of the NSDAP had existed since 1930, which was one of the first in the district after the one founded in Duderstadt in 1925.

The last months of the Weimar Republic were probably marked by violent political disputes, as the NSDAP, the Hitler Youth as well as the Reichsbanner , the DHP and the Center registered many events in 1932. A newspaper note from this time reports that a Lindau SA man "was seriously injured by a political opponent with a key on his head."

Lindau during National Socialism (1933–1945)

Unfortunately, no statements can be made about the voting behavior of the Lindau residents in the Reichstag elections in March 1933, which had already been carried out under strong pressure from the Nazis. No documents have been preserved. Presumably, however, there were no major changes to the previous elections, as this was not the case in the entire Duderstadt district.

At first, the people of Lindau remained skeptical of the new rulers. After the Concordat between the German Reich and the Vatican, however, many Catholics, who had previously always been skeptical of National Socialism, felt encouraged to join the NSDAP. Among other things, a respected horse dealer who would later become the second National Socialist mayor. He was a devout Catholic. In addition, the Nazi women's association was founded in Lindau , which was headed by a well-known Catholic woman from Lindau. Gradually, National Socialism also became socially acceptable among Catholics.

In May 1933, Heinrich Leinemann was appointed the first National Socialist mayor by the Upper President of Hanover. Even here the community no longer had any influence on its own politics. The new rulers determined everything.

In November of the same year "Reichstag elections" took place again. However, it was only possible to vote for yes or no . In these elections, 910 people from Lindau voted for the Nazi-occupied Reichstag, that is 98%. Only 19 votes (approx. 2%) were invalid or were no . It is noteworthy that the mood had turned. While the Nazis' share of the vote during the republic was always below the Reichs average, it was now 6% higher than in the rest of the Reich.

Immediately after the end of democracy and the beginning of Nazi rule, a local group of the Stahlhelm was founded in Lindau , an organization of former combatants that was close to the DNVP during the Weimar Republic. In many places, the steel helmet (initially) offered protection to those men who refused to join the local SA or SS organizations. If this organization in Lindau had only one member before 1933, the number of members has now increased rapidly. Many members of the now dissolved center as well as social democrats belonged to the Stahlhelm under the leadership of Emil Greve, a former, disappointed NSDAP member. But it was of no use to them: just two years later the Stahlhelm was dissolved across the empire.

Since the new Nazi mayor had sent a list of 23 Stahlhelm members to Duderstadt, with precise details of which party they belonged to and what statements they had made against the new state, Emil Greve had to contact the federal management of the Stahlhelm so that his group could join Lindau was allowed to continue. Greve received support from the federal management, which had turned to the Duderstadt district administrator. The latter then informed the state police station in Hanover and added a personnel sheet about Greve. The solution to the conflict is not known.

There was long speculation about the relationship between the Lindau dean box and National Socialism. Contemporary witnesses later reported that he suffered greatly under the Nazis. The opening of the church tower ball in 1994 brought clarity: Kasten was spied on and accused by the Nazis. He was saved by the amnesty imposed when the war broke out.

The entire Catholic Church suffered under the Nazis. It was like that B. no longer allowed to hoist church flags during the Corpus Christi procession; only swastika flags were allowed. The sermons in the church were listened to by party people who interfered with heckling and rioted in the church.

The evangelical pastor Burgdorf from Katlenburg , who had initially welcomed Hitler's accession to power and also preached in Lindau, fared no differently. He was also harassed. During the war, he occasionally expressed criticism of the NSDAP, which many church people elsewhere had to pay with death.

Immediately after 1933, Catholic institutions such as B. the kindergarten, in the sights of the Nazis. These facilities remained in place, but a kindergarten was also set up under the leadership of Nazi sisters with brown uniforms.

The Catholic and Protestant primary schools, which were housed in one building, were converted into a community school in 1939. There was therefore considerable resentment in Lindau, which reached as far as the Ministry of the Interior. After a particularly zealous National Socialist-minded teacher began his service there in 1937, the school developed into a model NS school. I.a. everything religious was banned from everyday school life.

In 1939 a scandal broke out in Lindau, which was reported in the entire region. Anonymous mocking poems appeared about Mayor Leinemann criticizing his way of life. After the Gestapo intervened , the clerk was found; it was a Lindau farmer who confessed to writing the letters. The party stood behind Leinemann, which is why a rally was held in Lindau with the participation of supposedly thousands of people against political Catholicism, according to newspaper reports. After the speech in which two men accused of this matter were " expelled from the national community ", some angry people stormed to the houses of the two and smashed glass panes and doors. A doctor and neighbors helped the vulnerable families.

The accused farmer was finally acquitted because he had motives for church politics. Lindau is a "stronghold of political Catholicism" , it was established.

After a while, Leinemann was deposed and replaced by the respected businessman Joseph Wagener. He treated the families expelled by the Nazis decently, and this also applied to all Lindau residents.

For a long time people in Lindau did not like to remember this process. Until the 1990s, the farmer's actions were viewed by some Lindau residents as a crime rather than a courageous act against the Nazi regime. Recalling the fact that under Heinrich Leinemann it had been possible to pay off the tax debt of the municipality of Lindau of 30,000 RM was easier.

Job creation measures in Lindau resulted in new roads and Ä. and more people were employed. Among other things, the market square was paved in 1938 and was used as a stage for many political rallies.

But, according to Mayor Leinemann, the connection of Lindau to the infrastructure remained “below all dignity” , which prompted him to appeal to the Duderstädter district committee to also consider a railway connection with Lindau. There was already a train station in Katlenburg and Bilshausen. Leinemann justified this with the 200-worker Greves factory, the Vlotho cigar factory with 80 workers and two very productive construction companies. But Lindau has not had its own rail link to this day.

The economy flourished, the Greve twine factory z. B. received many orders from the Wehrmacht . It was an upswing that can be explained by the preparations for the Second World War.

The Second World War (1939-1945)

The Lindau school chronicle described the outbreak of the war true to the Nazi guidelines: As early as May 1939, the “Führer” would have asked the Poles that the “originally German city” of Danzig should be returned to Germany. Supported by the British and French, this would have been rejected. From this point on, the German population living in the corridor would have been in a bad way, since they “tortured, maltreated and z. T. were killed ” , according to the school chronicle. On August 25, the Poles then occupied the Gleiwitz transmitter and sent out troops directed against the Reich. Today we know that the outgoing violence probably came from the Germans. The school chronicle continues: For this reason Hitler began to use “violence against violence” and to attack Poland. 70 Lindauer were called to arms.

As women and children from big cities began to be brought to the safer country quite early in the west of the Reich, 27 refugees came from the Saar in December .

The Lindau school chronicle reported during the war with particularly Nazi zeal. Among other things, she praised the fact that Lindau was “third in the Duderstadt district” when it came to the delivery of metal objects for war production. Furthermore, she reports that Hitler gave the British the offer "to come to an understanding with Germany" - Hitler hoped for an alliance of the Germanic peoples of Europe - but the British had this with "aimless and haphazard" bombing attacks on "non- military goals ” . The people of Lindau also had to go to the air raid shelter. The school chronicle breaks off in June 1941. From here on one should read more about it in the separate war chronicle, each parish had to lead it. But the Lindau war chronicle is lost. What has been preserved, however, is a booklet from the rectory, which was presumably kept by Dean Kasten.

When plane crashes over Lindau came z. B. 1945 a group of Canadian Air Force soldiers died. An American aviation officer was able to save himself with a parachute. He was temporarily locked in the Mushaus. Something similar happened to about twenty Soviet prisoners of war who were able to free themselves in an attack and were then also locked in the Mushaus. The people of Lindau fed them.

During the war, many prisoners of war came to Lindau, including French and Poles, some of whom were used in agriculture.

The Second World War killed 111 German soldiers, some of them were missing. This number is almost twice as high as that of the Lindau dead in the First World War 1914–1918.

The immediate post-war period (1945–1949)

One of the first steps after the end of the war was the release of prisoners of war. For many nights, the American soldiers who occupied Lindau imposed curfews. On May 10, 1945, the former central politician Anton Freyberg was appointed as the new mayor. In June 1945 about 200 Englishmen entered Lindau after the Americans left and stayed until 1946.

Little by little, life in Lindau began to normalize somewhat. On May 31, 1945, Dechant Kasten carried out a Corpus Christi parade. However, the Lindau riflemen, who had been with us for generations, were forbidden to carry weapons. On June 3rd, a new kindergarten was inaugurated and on June 5th, after all National Socialist ideas had been removed, the public library moved to the rectory.

One problem, however, was considerable: as some teachers at the Lindau School fell under the professional ban, there was a lack of teachers in some cases. Other problems existed a. in the availability of teaching materials: many books which the Allies considered to be too Nazi were sorted out, so that there was a shortage of books. The school's radio was found destroyed in the forest in 1946 and the camera no longer worked properly. “Apart from the Bible, catechism and some reading books, schoolchildren have nothing in terms of learning books,” wrote a teacher at the time.

After the ban on fraternization was lifted, there was a good relationship between the English occupiers and the people of Lindau . The English even played friendly matches with FC Lindau.

On March 16, the village school, which had been converted into a non-denominational community school after the war, was converted back into a Catholic school after an 88% vote by parents. However, the Protestant children received their own religious instruction.

The high number of refugees from major German cities was problematic for the place. There was simply insufficient food, shelter and employment. The number of refugees grew steadily, so that the population eventually rose to 2,400. All the houses were very busy, and the relationship between Lindau residents and refugees was not always good.

Between 1946 and 1948, Fleckenstraße was paved in a joint effort, and the church tower was repaired in 1948. Old documents were removed from the church tower button, which had served as a storage place for documents over the years, and new ones were inserted, which came to light again in 1994.

Development since 1949 until today

After the Second World War, Lindau got a new building area north of the main road and the entire infrastructure was improved.

In 1957 the place received a multi-purpose hall, which was built on Schützenallee. This hall was extensively renovated in 2006. A few meters in front of it, a new, larger elementary school was built in 1965, which today serves as a secondary and secondary school. A new, modern kindergarten was also built in 1969. It is still in Catholic hands today. During this time, Lindau also got its own sports field, which at the time cost 62,000 DM. A new fire station was built in 1971 and the streets were paved and equipped with modern lighting.

Lindau has had a partnership with the southern German town of Binau since 1966 . To this day, there are close ties between the two villages and people often visit each other. For example at the 1200th anniversary of Binau in 1971. Since 1975 there has been a "Lindauer Straße" in Binau and since 1978 a "Binauer Straße" in Lindau.

The local council made an important decision in 1969: Lindau was to get a local sewer system, which is why it joined the "Rhumetal" sewage association just a few months later. In 1976 the project was completed.

An important local political event for Lindau followed on January 1, 1973. In the course of the Lower Saxony regional and administrative reform , the district of Duderstadt was dissolved and Lindau was the only place incorporated into the district of Northeim . At that time, however, the question arose whether Lindau should not be incorporated into the Göttingen district because it was part of the Eichsfeld district. The population was divided on this issue. If Duderstadt had remained the district town, it is very likely that the old district town would have been voted for. In the decisive council meeting, eight councilors voted for Northeim and five for Göttingen. Lindau lost the status of a municipality on March 1, 1974. The municipality of Katlenburg-Lindau was founded together with six other localities. The new name of the community had long been debated, including whether one should perhaps work with Wulften or Bilshausen. In terms of name, the name that still exists today prevailed against Lindau-Katlenburg, which was preferred by Lindau . Katlenburg became the administrative seat.

After the local council had made the decision to go to Northeim, the death knell rang at the Catholic Church. Even Der Spiegel reported about it. The reason for this was, according to Spiegel, that the population of the Northeim parishes is "for the most part Protestant" .

Lindau only got a natural gas connection in 1983 . Since the district road to Gillersheim was being rebuilt, the corresponding pipes were laid under it. In the same year the extensive renovation work on the Church of St. Peter and Paul was completed. The work took seven years and the renewal of the organ alone cost 100,000 DM.

Since 1985 Lindau has had a large sports hall with a grandstand for 250 spectators. The costs for this amounted to 2 million DM.

The mill ditch at the Mushaus, created in 1872 by the Greve company to generate energy, was filled in in 1984. The old bridge railing is the only one that still reminds of the river at that time.

In 1987 the Northeim district in Lindau created the “Center for Innovation” in the vicinity of the Max Planck Institute. It is intended to offer low-cost production facilities to high-tech companies.

In 1946, 1947, 1981 and 1994 Lindau was hit by severe floods in the Rhume, which caused great damage. The flood dam, which has existed since 1995, has prevented similarly serious floods to this day.

In June 2011, the local council of Lindau unanimously decided on a motion by the SPD to reintroduce the name Flecken Lindau, which had been omitted in the course of the administrative reform of 1974 . Since November 14th 2011 Lindau is officially a place again.

In July 2011, the Klingenberg spring was extensively prepared by the citizens of Lindau. Over 200 people attended the inauguration.

Plane crash over Lindau

October 29, 1979 brought the place name "Lindau" into all media in the Federal Republic of Germany and beyond. At 5:07 p.m., a US reconnaissance aircraft of the “ Grumman Mohawk ” type fell on the property of farmer Karl Linnekuhl directly on the B247 to Bilshausen and set the stables on fire. There was property damage of 500,000 DM. Both pilots were able to save themselves with the ejection seat. It later emerged that the two pilots had succeeded in keeping the crash away from the densely populated area of Lindau, thus preventing a major catastrophe.

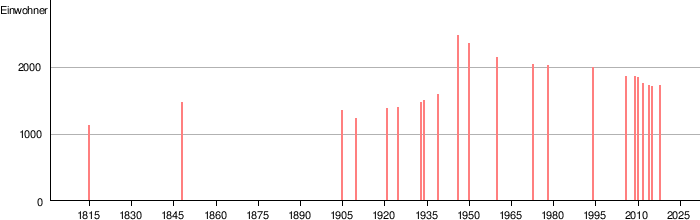

Population development

|

|

¹ 194 fireplaces

² in 250 residential buildings

Over the years, the size of the Lindau population fluctuated considerably. The number of inhabitants was strikingly high in the period immediately after the Second World War , but this can be explained by the fact that among the 2456 inhabitants in 1946 there were 861 refugees. This is a phenomenon that could not only be observed in Lindau. Due to their location on the edge of the zone, several villages and towns in what is now southern Lower Saxony became "reception camps" for refugees who either lost their home in the former German areas east of the Oder or who fled from the Soviet occupiers in what is now the eastern German states. However, some also consisted of former forced laborers. The number of residents has been falling significantly since the 2010s and is currently approaching the pre-war level.

politics

Local council

|

The Lindau local council consists of 11 council members from the following parties: (Status: local election September 11, 2016) Local mayor

(Source:) |

Chronicle of the mayor or local mayor

|

|

coat of arms

| Blazon : “Above a green shield base , inside two continuous silver corrugated strips , in gold a red tower with a high gable roof , followed by a piece of a red battlement wall on both sides; In each of the upper corners a two-leaved green linden branch is floating. " | |

Justification for the coat of arms: Klemens Stadler says in his book:

|

partnership

-

Binau , municipality in Baden-Württemberg ( Germany ), since 1966

Binau , municipality in Baden-Württemberg ( Germany ), since 1966

Culture and sights

Buildings

The Mushaus

Around 1322, the Hildesheim bishop Otto II built the Mushaus in the castle district, today the oldest building in the municipality of Katlenburg-Lindau, which housed the Lindau administration until 1741. A certificate from the same year states that Gottschalk and Hermann, noblemen of Plesse , Otto II had sold the village including the castle, patronage rights , bailiwick and people. The sum is said to have been at least 1400 soldering marks. A year later, the noble lords of Plesse subordinate their feudal people under the sovereignty of the Hildesheim bishop.

The high-rise Mushaus , visible from afar , has been on the coat of arms of Lindau since 1951. The name "Mushaus" (also written "Mußhaus") is derived from the delivery of farmers to their master (from Middle High German mute , for toll, customs, toll station). In a chronicle, the Lindau building is also referred to with the Latin word palacium (Palas, house of the ruler).

After 1322, the Hildesheim bishop Otto II took possession of Lindau Castle, which already existed in front of this building. Construction probably started around this time, and an exact date cannot be determined. The Mushaus survived the many centuries, presumably because of the several meters thick walls that can hardly be destroyed.

In the 1870s, the Lindau factory owner August Grewe bought the building and used it for his workers. In 1978 the windows of the Mushaus were closed with wooden hatches and the roof was renovated. Today the Mushaus is empty and has no use. It is considered to be one of the oldest, fully preserved secular buildings in Lower Saxony.

According to old documents, there were other buildings in the immediate vicinity of the Mushaus, which together formed the Lindau Castle. The other structures were probably destroyed in the Thirty Years War.

It can be assumed that there was a forerunner system southeast of the Rhumebrücke for the Lindau Castle and the Mushaus. Even today you can see faint traces in the terrain that have not yet been explored.

Catholic Church of Saints Peter and Paul

The Catholic Church of St. Peter and Paul in Lindau is one of the most splendid churches in the lower area. The tower of the baroque church dates from 1523. The foundation stone for the church as we know it today was laid on October 17, 1755 by Duderstadt Commissioner Huth. After ten years, however, the nave collapsed because the church vault was too heavy for the walls. When they were supposed to remove the roof of the church in 1765 as a precaution, construction workers had placed too much wood on the scaffolding. Two workers were killed in the collapse. The church was rebuilt between 1765 and 1771, which brought the church a debt of 3800 thalers.

Under the choir pavement there is a vaulted crypt for the noble family von Walthausen. Inside lies the lieutenant general and commandant of Göttingen, Georg von Walthausen, who died in Göttingen on November 14, 1776 and was buried in the church on November 20. His wife Ludovica von Walthausen, who died on May 1, 1795 and was also buried in the crypt on May 5, rests next to him. As Johann Vinzenz Wolf writes in his chronicle about Lindau, both would have done a lot of good for the church.

Extensive renovation work last took place between 1977 and 1982.

The slated west tower is visible from afar and one of the landmarks of the Eichsfeldort. The altarpiece (1700) comes from St. Godehard's Basilica (Hildesheim) . The choir stalls were built in the 18th century and were taken over from the St. Jakobus Church in Goslar in 1982 . The way of the cross, also from the 18th century, is a specialty; it comes from the former Cistercian convent Teistungenburg. The organ dates from 1882 and was manufactured by Louis Krell . In 1984 it was restored by the Gebr. Krell organ building workshop in Duderstadt under the direction of Werner Krell, the great-grandson of Louis Krell.

In 1956, the Lindau parish got a branch church in Katlenburg, the Herz-Jesu-Kirche , which, however, changed to the parish in Northeim in 2006 and was profaned in 2009 .

Since November 1st, 2014 the Lindau Church belongs to the parish “St. Kosmas and Damian ”in Bilshausen .

Evangelical Kreuzkirche

This Protestant church was built from April 22nd, 1894 until its inauguration on August 4th, 1895 under the direction of the architect Conrad Wilhelm Hase . Today the church is located directly on Bundesstraße 247.

This building is a single-nave neo-Gothic hall church made of brick. It has a protruding facade tower, the gable roof of which is crowned with a pointed roof turret. In the church there is a vaulted polygonal altar niche with a figure-filled predella and crucifix typical of the 19th century. The two church bells were commissioned from the Hildesheim company JJ Radler at the beginning of 1895 and tuned to the notes b and d flat in the one- and two-stroke octave. The metal mixture of the bells consists of copper and tin.

During the last renovation in 1994, the church was restored to its original interior condition. The design made of natural wood, clinkered opening reveals as well as painted wall and roof surfaces came to the fore again.

The Kreuzkirche belongs to the Landeskirche Hannover and from 1960 to 2013 the parish of Herzberg, now the parish of the Harzer Land .

War memorial

In order to honor the soldiers from Lindau who fell in World War I, it was decided in 1920 to erect a war memorial.

The realization of this project should be made possible through donations. In 1920 they had already collected 1,292 RM. By March 1923, donations from associations and companies had raised RM 797,829. But the massive inflation of the crisis year 1923 soon made the money worthless, so that by August 10 to 12,000,000 RM would have been needed for the construction. For this reason, the plans were initially dropped.

In order to allow the construction to take place anyway, the artist Georg Greve designed a postcard showing a draft of the monument. The proceeds made it possible, among other things, to still be able to implement the project. The war memorial was erected in 1924 next to the old school on today's federal road.

Today the memorial is in the Lindau cemetery.

Murder mill

The legendary murder mill is located between Lindau and Gillersheim. According to an old legend, a bloodbath of robbers is said to have taken place here, who were struck down by a miller maid who was supposed to guard the mill while the millers were away. Hence its unusual name.

The mill, which is located about 500 meters from the outskirts of Lindau, has a characteristic mill homestead, which consists of a residential house and the farm buildings. The over 80 year old mill operating system is still fully functional today and gets its water from a small mill ditch.

The murder mill was created in different epochs, which is evident from the different structural elements. Often the mill had to be rebuilt, such as B. after Tilly's troops destroyed the mill in the Thirty Years War .

For a long time, the future of the murder mill was uncertain. Since it threatened to disintegrate, the association “Freunde der Mordmühle e. V. ”was founded, which made a decisive contribution to the continued existence of the mill. In this way, the association managed to find a new owner for the mill and to restore the historic mill ditch, which was threatened with filling.

Today the mill is the scene of the annual German Milling Day . On Mühlentag 2005 a play by the then chairman of the association, Rudolf Brodhun, was performed. The historical murder mill saga was performed at the "original locations".

The murder mill is now a listed building.

Office building (demolished)

The Mushaus was renovated in 1664, but in the 18th century it no longer met the requirements of the seat of an official administration. Therefore, a new office building was built in the immediate vicinity, which became the seat of the Mainzischen Amt Lindau. The construction of the building was completed in 1741, as can be seen above the archway of the former magnificent door, which is under monument protection and is located in the Lindau secondary school. The client was Philipp Karl, the 74th Elector of Mainz , who was sovereign of Eichsfeld and thus also of Lindau.

Until 1859 this building remained the seat of the office and the district court of Lindau . When it lost this function in the course of an administrative reform, it became the residence of the Grewe family from 1872 after it had been empty for a few years. At the beginning of the 1970s no further use was found for the now dilapidated office building, while a new building for the municipal administration was acquired in Katlenburg at the same time. In 1974 this beautiful baroque building was demolished a few days before it was to be listed as a historical monument. Only the portal has been preserved.

Brewery (demolished)

The former brewery was located near the Lindau market square, next to the fire station.

Since the Middle Ages, Lindau, like Gieboldehausen and Duderstadt, had had the right to brew their own beer . In 1683 the market town also got permission to sell it in the surrounding villages. The hops for brewing beer had been grown themselves. The name "Hopfenberg", which a mountain bears a little outside the village, still reminds of this tradition. From the 19th century, however, the brewery increasingly lost its importance and was closed around 1850.

In the 19th century the building mentioned here was the location of the Lindau brewery. Until recently, this house (Marktstrasse 8) was still used as a residential building. This historic half-timbered house was demolished on October 30, 2007.

societies

The village of Lindau has quite a few clubs, some of which can look back on a long history, such as the Lindau shooting club from 1438, the Concordia Lindau men's choir from 1849 or the Lindau fanfare procession from 1953.

economy

The Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) was based in Lindau from 1946 to 2014 . In 2014 it moved to Göttingen.

Lindau has been the seat of a Buddhist LiuZu center since 2017 . In future it will be the German and European headquarters of the Hubei LiuZu Culture Transmit. It is located on the premises of the former MPS.

Personalities

Honorary citizen

- Igna Maria Jünemann (writer), 1964

- Walter Dieminger (scientist), 1975

Sons and Daughters of the Spot

- Christian Liebrecht (born January 25, 1703; † 1793), professor of theology and morals at the University of Bamberg

- Johann Heinrich Pabst (born January 25, 1785, † July 28, 1838 in Döbling near Vienna), doctor and philosopher

- Georg Greve (1876–1963), impressionist painter

- Franz Mueller-Darß (1890–1976), forester and standard leader of the Waffen SS on Heinrich Himmler's staff

- Wilfried Gleitze (born September 8, 1944; † November 21, 2019 in Münster), lawyer, First Director of the German Pension Insurance Westphalia (1987–2009), Vice President of the Federal Insurance Office (1981–1987)

People connected to the stain

- Adolf Dörge (1938–2012), physician and university professor for physiology

- Margrit Poremba (* July 18, 1955 - November 1, 2015), music dramaturge, died in Lindau

literature

- Birgit Schlegel, Rudolf Brodhun a. a .: Lindau - history of a patch . Mecke Druck Verlag, 1995, ISBN 3-923453-67-1 .

- Maria Hauff, Hans-H. Ebeling: Duderstadt and the Lower Field . Mecke Druck Verlag, 1996, ISBN 3-923453-85-X .

- Rolf-Günther Lucke u. a .: The churches in Eichsfeld . Mecke Druck Verlag, 2005, ISBN 3-936617-41-4 .

- Johann Wolf : Memories of the office and Marcktfleckens Lindau in the Harz department, District Osterode . JC Baier Verlag, Göttingen 1813 ( digitized in the Google book search).

- Markus C. Blaich , Sonja Stadje, Kim Kappes: Mushaus in Lindau in: Die Heldenburg bei Salzderhelden, castle and residence in the Principality of Grubenhagen , (= guide to the prehistory and early history of Lower Saxony. 32) Isensee Verlag , Oldenburg, 2019, p. 127 -128.

Web links

- Flecken Lindau on the website of the community Katlenburg-Lindau

- Local councilor Lindau on the website of the municipality Katlenburg-Lindau

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Figures, data, facts. In: Website of the municipality of Katlenburg-Lindau. July 1, 2018, accessed November 30, 2019 .

- ^ Johann Wolf: Eichsfeldisches Urkundenbuch together with the treatise of the Eichsfeldischen nobility . Treatise on the Eichsfeld nobility, as a contribution to its history. Göttingen 1819, p. 37-45 .

- ^ Hermann Bringmann: Reformation and Counter-Reformation in the Untereichsfeld, illustrated using the example of the village of Bilshausen . In: The Golden Mark . 27th year. Issue no. 3. Karl Mecke Verlag, Duderstadt 1976, p. 53-65 .

- ↑ Bernhard Sacrifice man : shaping the calibration field . St. Benno-Verlag / FW Cordier Verlag, Leipzig / Heiligenstadt 1968.

- ^ Federal Statistical Office (ed.): Historical municipality directory for the Federal Republic of Germany. Name, border and key number changes in municipalities, counties and administrative districts from May 27, 1970 to December 31, 1982 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart / Mainz 1983, ISBN 3-17-003263-1 , p. 214 .

- ↑ Lindau is to become stains again. In: Website Göttinger Tageblatt / Eichsfelder Tageblatt . June 24, 2011, accessed November 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Sebastian Rübbert: New signs with historical names. In: Website Göttinger Tageblatt / Eichsfelder Tageblatt. March 2, 2012, accessed November 30, 2019 .

- ^ CH Jansen: Statistical Handbook of the Kingdom of Hanover (= Statistical Handbooks for the Kingdom of Hanover ). Helwing'sche Hofbuchhandlung, Celle 1824, p. 374 ( digitized version in Google Book Search [accessed November 30, 2019]).

- ↑ Friedrich W. Harseim, C. Schlüter: Statistical Handbook for the Kingdom of Hanover (= Statistical Handbooks for the Kingdom of Hanover ). Schlüter'sche Hofbuchdruckerei, Hanover 1848, p. 80–81 ( digitized in Google Book Search [accessed November 30, 2019]).

- ^ A b c d Michael Rademacher: German administrative history from the unification of the empire in 1871 to the reunification in 1990. Landkreis Duderstadt ( see under: No. 17 ). (Online material for the dissertation, Osnabrück 2006).

- ^ Ulrich Schubert: Municipal directory Germany 1900 - Duderstadt district. Information from December 1, 1910. In: gemeindeververzeichnis.de. February 3, 2019, accessed November 30, 2019 .

- ^ Federal Statistical Office (ed.): Official municipality directory for the Federal Republic of Germany . Final results according to the September 13, 1950 census. Volume 33 . W. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart / Cologne August 1952, p. 33 , col. 2 , Landkreis Duderstadt, p. 42 ( digitized [PDF; 26.4 MB ; accessed on November 30, 2019]).

- ↑ Lower Saxony State Administration Office (ed.): Municipal directory for Lower Saxony . Municipalities and municipality-free areas. Self-published, Hanover January 1, 1973, p. 32 , District of Northeim ( digitized [PDF; 21.3 MB ; accessed on November 30, 2019]).

- ↑ a b Members of the Lindau local council. In: Website of the municipality of Katlenburg-Lindau. Retrieved November 30, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Klemens Stadler : German coat of arms of the Federal Republic of Germany . The municipal coats of arms of the federal states of Lower Saxony and Schleswig-Holstein. tape 5 . Angelsachsen-Verlag, Bremen 1970, p. 56 .

- ↑ Lindau coat of arms. In: Website of the municipality of Katlenburg-Lindau. Retrieved November 29, 2019 .

- ^ Hans Sudendorf: Document book on the history of the dukes of Braunschweig and Lüneburg and their lands . Rümpler Verlag, Hanover 1859, p. 203 .

- ^ Johann Wolf: Memories of the office and market town of Lindau . Göttingen 1813, p. 55 .

- ^ Carl-Heinz Engelke: Lindau. History of a patch in northern Eichsfeld . Hunter years Evangelical Kreuzkirche in Lindau. Ed .: Birgit Schlegel. Mecke Verlag, Duderstadt 1995, ISBN 3-923453-67-1 , p. 239 .

- ↑ Monks inaugurate the center in Lindau. In: Website Hessische / Niedersächsische Allgemeine . June 28, 2017. Retrieved November 30, 2019 .

- ^ Johann Wolf: Memories of the office and market town of Lindau . Göttingen 1813, p. 64 ff .

- ↑ Johann Heinrich Pabst. In: Website German Biography. Retrieved November 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Former DRV director has died. Wilfried Gleitze: A champion for the pension insurance. In: Website Westfälische Nachrichten . November 27, 2019, accessed November 30, 2019 .

- ^ Margit Poremba obituary notice. In: Website Hessische / Niedersächsische Allgemeine . November 11, 2015, accessed November 30, 2019 .