Macedonia

| Geographical Macedonia | |

|

Today's breakdown: Smaller areas: |

Macedonia or Macedonia ( Greek Μακεδονία Makedonía ; Macedonian and Serbian Македонија Makedonija ; Bulgarian Македония Makedonija ; Turkish Makedonya ; Albanian Maqedoni / -a ) is a geographical and historical area in the southern Balkan peninsula .

Today the area includes the region of Macedonia in North Greece , the Republic of North Macedonia and the Blagoevgrad Oblast in southwest Bulgaria . Other smaller parts belong to South Kosovo , South Serbia and Southeast Albania .

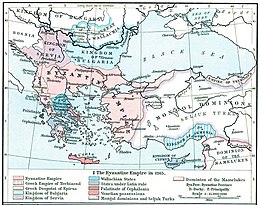

The size of the area known as Macedonia has changed several times throughout history since the ancient Kingdom of Macedonia took shape and expanded. When the region was part of the Ottoman Empire , the name Macedonia was temporarily out of use. It was not revived until the middle of the 19th century. It was now used to designate a geographical region and was entered on maps. The understanding of the expansion of Macedonia at that time was roughly the same as it is today. The Balkan Wars of 1912/13 ended the rule of the Ottoman Empire and led to the division of the area into different states.

history

Antiquity (approx. 1400 BC to 600 AD)

The question of how “ Greek ” the ancient Macedonians were is still politically explosive today. The modern Greeks claim that Alexander the Great and the rest of the Macedonians are Hellenes , and Macedonia was a part of Greece then as it is today, which is why the self-designation of the modern, Slavic state of North Macedonia as Macedonia and Macedonia is often seen as a provocation. This also influences the scientific discussion.

The area of the later Macedonia was already settled in the Neolithic Age. According to a controversial research view, the Macedonians are together with the Northwest Greeks around 1200 BC. Immigrated to the area and settled there. Some ancient historians, however, describe the Macedonians as a mixed population of Phrygians , Thracians and Illyrians who did not immigrate as a Greek tribe. Many researchers see the ancient Macedonians as a northern Greek tribe that differed culturally from the rest of the Greeks due to close contacts with Thracians and Illyrians, but this is still doubted by a large minority who suggest that ancient sources up to Strabo had the Macedonians often expressly not regarded as Greeks, but as barbarians ( see below ), or fluctuated in their classification. There are arguments for both positions: For example, an author like Hesiod considered the Macedonians to be a Greek tribe, but at the same time the Macedonians were forbidden from participating in panhellenic competitions, especially the Olympic Games , until the beginning of Hellenism ; an exception was only made for the Macedonian royal dynasty of the Argeads . Conversely, in the late 4th century BC. Chr. Eumenes von Kardia to fight with acceptance problems with his Macedonian soldiers, because they did not want to be commanded by a Greek.

There are also different views on the Macedonian language , because the sources are ineffective, and Macedonian may have died out in antiquity. The Macedonians spoke an Indo-European language , which is probably part of the "western branch" of the Balkans Indo-European and was at least related to Greek . This view is the widespread view among linguists and historians - such as Ivo Hajnal , Hermann Bengtson , Nicholas G. Hammond, and Robert Malcolm Errington .

Before the 19th century there was never a Greek nation-state, but rather the community of Greek small and city-states linked by common culture, religion and language. The aforementioned participation of members of the Macedonian royal family in the Olympic Games , which in classical times was only permitted to Greeks, was therefore of particular importance . It is first attested for King Alexander I, who lived around 500 BC. Before he took office, he was admitted to Olympia as a young man because he was able to convince the priests there that he was a descendant of Heracles and Achilles and therefore a Greek. 408 BC The four-team of the Macedonian king Archelaos I won the Olympic chariot race. As already mentioned, this recognition of Hellenism referred exclusively to the royal family, not to the Macedonians as a people. This is also made clear by the speech to the Macedonian king Philip II , which the Athenian Isocrates published in 346 and sent to the ruler. In it he declares that Philip's ancestors, as Greeks, had gained control over a non-Greek people, the Macedonians; A monarchy is appropriate for this barbarian people, but the Greeks cannot tolerate this form of rule, because barbarians have to be forced, but Greeks have to be convinced. All of this suggests that the ancient Macedonians were, from the point of view of contemporaries, a kind of “ semi-barbarian ” who, depending on the context and intention, could be denied their Greek status. The question of whether the Macedonians were Greeks cannot therefore be answered conclusively with the current state of research, even if researchers such as Hans-Ulrich Wiemer are convinced that they were Greeks, especially in Athenian sources (especially Demosthenes ) from political sources Reasons the Hellenism had been denied.

For a long time Macedonia was only an insignificant region. King Archelaos I (413–399 BC) first laid the foundation for the position of great power. Many Greek scholars and artists were drawn to his court under his rule. Another important king was Perdiccas II , a contemporary of the Thracian king Sitalkes . Within a few years, however, Macedonia did not become the leading power in ancient Greece until 356 BC. By King Philip II. He was able to firmly connect Upper and Lower Macedonia for the first time by subjugating several Macedonian petty kings and raising their children as hostages at his court; he also reorganized the army and began to expand the Macedonian sphere of influence through conquests and subjugations. The expansion of Macedonian rule under Philip II quickly brought the Kingdom of Macedonia into conflict with Athens , which saw its interests in the northern Aegean region (ore mining in the Pangeo Mountains, settlements and trading bases on the Chalkidiki ) endangered. To make matters worse, Philip II's predecessors in the Peloponnesian War from 431 to 404 BC With the Athenian war opponent Sparta had partially formed a coalition. Initially, however, the Kingdom of Macedonia was not the undisputed ruler of the region. The Chalkidikische Bund , a Greek city federation under the leadership of the Polis Olynth , was able to conquer parts of Macedonia ( Anthemoundas Valley on the Thermaic Gulf and Mygdonia ) and even threatened Pella at times , without being able to besiege or attack it. Because of these conflicts of interest, Philip II initially led a cautious, tactical foreign policy with partly changing alliances, which in the end allowed him to consolidate and subsequently expand his sphere of influence. The conflict with Athens became evident with the capture of Amphipolis east of the ore-bearing Pangeo Mountains by Macedonian troops under Philip II. The attempts of Athens, especially the politician (demagogue) Demosthenes , in the conflict of the Second Olynthian War 350 to 348 BC. To intervene in favor of Macedonia's opponent, the Chalkidikischen Bund under the leadership of Olynthus, was insufficient and too late. Philip II destroyed in 348 BC Chr. Olynth, dissolved the Chalkidikischen Bund and had afterwards "the back for a dispute with the Greek city-states."

Again Philip II did not directly open a campaign against the Greek Poleis , but gained respect and recognition as well as a seat on the Council of Amphictyony with his intervention in the Third Holy War of the Delphic Amphictyony , a religious league of the Greek city-states. He received the seat in the Amphictyon Council with two votes for himself personally because of his merits, not as a representative of the Macedonians, who, unlike the royal family, were still not recognized as Greeks. Despite this integration of Philip as a “Greek”, tensions between him and Athens and the other Greek city-states, with the exception of Thebes , remained. Under Athenian leadership, the Greek city-states rose against the threatening Macedonian hegemony over the entire territory of Greece, but were defeated in 338 BC. Defeated by the Macedonians under the leadership of Philip II and his son Alexander at the Battle of Chaironeia .

The Macedonian king now united the divided and mostly divided Greek city-states in the Corinthian League on the basis of a general peace and thus created a united Greece for the first time in history, with the exception of Sparta and the Greek colonies in the western Mediterranean . Regardless of this agreement, the Corinthian League laid down the military succession of the Greek city-states against Philip II and the Kingdom of Macedonia, which was also a symbol of Macedonian hegemony over the Greek city-states. On the then northern Macedonian border, Philip II conquered the Lynkestis landscape (corresponds to the region around the Prespa lakes ).

As from 338 BC at the latest The Macedonians coined the term “Macedonia” for the state structure that was being formed. "Epeiros" (Greek: "mainland") was also used to describe the landscape . The form of government was the monarchy . The king was elected by the army assembly. The decisive factor for the Macedonian (military) successes were above all the army reform of Philip II with the introduction of the Macedonian phalanx technique and the sarissa .

Macedonia reached the height of its power under Philip's son Alexander the Great . Under the pretext of a "campaign of revenge" for the Persian invasion of Greece 170 years earlier, he led 334 BC. An all-Greek army to Asia Minor and defeated the Persians in three battles - at Granikos , at Issus and Gaugamela . He conquered Egypt and the Persian heartland one after the other and extended his empire to the Hindu Kush and the Indus . With this he created the prerequisites for the Hellenization of the whole of the Near East . After Alexander's death in 323 BC In Babylon the great empire disintegrated under the battles of its successors, the Diadochi , who were almost without exception Macedonians. The rule of the Seleucids emerged from the Alexander Empire in Western Asia and that of the Ptolemies in Egypt . This Macedonian dynasty was to rule the country on the Nile for 300 years, until Queen Cleopatra's death in 30 BC. The rule of the Macedonian Seleucids was already 64 BC. Was ended by Pompey .

The kingdom of Macedonia itself, on the other hand, which had lost countless men in the Alexanderzug and in the bloody Diadoch Wars, initially lost importance; there was a tumult of the throne. In 280 BC An army of around 85,000 Celtic warriors marched to Macedonia and central Greece as part of the Celtic migration to the south . However, after they were defeated by Antigonus II Gonatas in 277, they settled in Thrace ( Tylis ) and Anatolia ( Galatians ). Antigonus II took advantage of the prestige he had gained through his Celtic victory and established himself on the throne, and the Antigonid dynasty was able to make Macedonia supremacy over Hellas for over a century; However, their sphere of influence shrank as a result of three Macedonian-Roman wars : The energetic King Philip V led the first two of these wars and lost after the end of the second in 196 BC. The hegemony over Greece. His son and successor Perseus was the last Macedonian king: 168 BC. After an extremely bloody third war , Rome forced the end of the Antigonid kingship and the division of Macedonia into four independent regions. These in turn were formally incorporated into the Roman Empire 20 years later as the province of Macedonia , which had now risen to become the leading power in the eastern Mediterranean. There is some evidence that most of the Macedonians either perished in the fighting during these years or left the country to settle in Asia Minor , and in some cases in Egypt. According to the inscriptions that were placed in the area between 168 and Augustus , at least the Macedonian language seems to have fallen out of use, and people from Thrace, Illyria and Greece are now supposed to have replaced the Macedonians. Little is known for certain about the history of Macedonia during this period.

Since the establishment of the Roman Empire by Augustus, the area experienced a certain boom. During the division of the empire in 395 AD, the country fell to the Eastern Roman Empire , which was culturally and linguistically influenced by Greek. In the 4th and 5th centuries the Huns and Goths raided Macedonia, but did not settle there. Late antiquity ended in this region with the Slavs and Avars invasions in the late 6th century .

Macedonia in the Middle Ages (582–1371)

Slavs have settled in the Balkans since the 7th century , including Macedonia and large parts of Greece. This led to profound ethnic changes: the Slavs mingled with the local population, which was composed of Paionen (proto- Bulgarian tribes from Paionia under the leadership of Kuber ), ancient Macedonians and other ethnic elements. As early as the 7th century, Macedonia was evidently so influenced by Slavs that Byzantine sources also referred to it as Sklavinia (Σκλαυινία) . However, the Byzantine culture remained in the cities for a long time. In the Eastern Roman-Byzantine Empire, the Slavs became an important factor and secured extensive settlement areas mainly in the heartland of geographical Macedonia and Thrace, while the Greeks traditionally settled on the coasts except for a few islands in the interior.

Since the 8th century, the name Macedonia was transferred to another geographical area further to the east, which neither corresponded to the Macedonia of antiquity nor to the current geographical name. The medieval Macedonia thus comprised a different region, with the City of Adrian Opel as a center, which in today Thrace was. It was not until classicism and the independence movements of the Balkan peoples that the region got its ancient name back; in the Middle Ages it was known as Pelagonia or Kisinas.

In the 9th century, most of today's Macedonia region came under the rule of the first Bulgarian empire with the ruler Krum Khan . In 811 the Byzantine Empire lost the battle of the Warbiza Pass against the First Bulgarian Empire. In 813 the Byzantine defeat against the first Bulgarian empire was repeated in the battle of Adrianople . The Byzantine sphere of influence subsequently shrank in favor of the Bulgarian one; especially Thrace and Macedonia came under the control of the Bulgarian Empire with its rulers Presian I (836–852), Boris I (852–889), Simeon I (893–927) and Peter I (927–969) . Around this time there was a Christianization of the population, as well as the spread of Slavic literature, which was written in Glagolitic and Cyrillic script. After the death of Tsar Peter in 969 the first Bulgarian empire showed signs of disintegration. The Byzantine Empire under Emperor Basil II. (Bulgarian Wasilij II.) Bulgarroktonos (the " Bulgar slayer ") was able to defeat the Bulgarians under Tsar Samuil in the Battle of Kleidion on July 29, 1014 .

Subsequently, today's region of Macedonia was reintegrated into the Byzantine Empire after a century. In 1185, the Normans besieged Thessaloniki after arriving from Italy on what is now the Albanian coast near Durres . In 1204 in the fourth crusade, the Byzantine capital Constantinople fell to the crusaders, who subsequently established crusader states . The southern parts of the geographic region were placed under the control of the Kingdom of Thessaloniki with its King Boniface of Montferrat . Immediately after the establishment of the Latin empires and kingdoms, armed conflicts broke out between the Latin states and the Bulgarian Empire. In 1205 the Latin Empire of Byzantium was defeated by the Bulgarians under Tsar Kaloyan in the Battle of Adrianople and lost its Emperor Baldwin in Bulgarian captivity.

The second Bulgarian empire succeeded in establishing control over large parts of the north of today's region of Macedonia (and Thrace) in particular. In 1207 the king of Thessaloniki Boniface von Montferrat died in a skirmish with Bulgarian troops; In the same year the Bulgarian Tsar Kalojan died during the siege of Thessaloniki. Subsequently, the dominion of the Kingdom of Thessaloniki shrank in the north and north-east under pressure from the Bulgarian Empire and in the south-west and west under pressure from the despotate of Epirus. In 1224 the southern part of ancient Macedonia was conquered by the despotate of Epirus with the capture of the city of Thessaloniki. The expanding despotate of Epirus then came into conflict with the expanding Bulgarian empire.

With the Battle of Klokotnitsa , which was victorious for the Bulgarians and the second Bulgarian empire under Tsar Ivan Assen II in 1230, the geographical region of Macedonia was placed under the control of the second Bulgarian empire. In 1259, with the Battle of Pelagonia, the southern parts of the geographical region of Pelagonia fell back to the Byzantine Empire. In 1321 a civil war broke out in the Byzantine Empire, which also affected the south of the Macedonia region. In the course of this civil war, farms and properties were destroyed. In 1330, the Bulgarian ruler Michail Schischman Assen led a campaign against northeast Macedonia, which was directed against the Serbian king, but failed in the battle of Welbaschd . The unrest that had already become visible in the Byzantine civil war continued with uprisings in the cities of Pelagonia . The most prominent of these uprisings was the Zealot rule in Thessaloniki from 1342 to 1349, which led to the extensive disempowerment of the Byzantine nobility and clergy in Thessaloniki.

In the middle of the 14th century until 1355, the Serbian kingdom under Stefan Uroš IV. Dušan conquered the entire present-day region of Macedonia with the exception of Thessaloniki and its immediate surroundings and also large parts of mainland Greece. After his death in 1355, Serbian control could not hold, and the areas including the ancient region of Macedonia came under Byzantine rule again for a short time.

Macedonia as part of the Ottoman Empire (1371–1912)

Conquest by the Ottoman Empire

The geographical region of Macedonia was gradually conquered by the Ottoman Empire from 1371 . In 1369 the Ottoman Empire under Sultan Murat I made Adrianople its capital. In 1371 a combined Serbian-Bulgarian force under the Serbian kings Jovan Uglješ and Vukašin Mrnjavčević ( Serres region and Prilep region ) was defeated by the Ottoman army in the Battle of the Maritza . After this victory, the Ottomans continuously expanded their territory to the west and thus also got the Macedonia region under control. In 1387 the city of Thessaloniki fell to the Ottomans. In 1389 there was the battle on the Blackbird Field , which the Ottoman Empire won again and thus consolidated its rule in the Macedonia region. The occupation of Skopje took place in 1392.

Neither Bulgaria nor the Byzantine Empire could do anything to counter the Ottoman expansion. In 1402, Emperor Manuel II was able to win back Thessaloniki diplomatically by skillfully navigating the Ottoman Interregnum that broke out after the Turkish defeat against the Mongols , but Byzantine rule remained limited to the city and its immediate surroundings ( Kassandra peninsula and western Chalkidiki ). As early as 1423, the Byzantines allowed a Venetian garrison to be stationed in Thessaloniki and on Kassandra. The help of Venetian troops could not stop the Ottoman expansion: In 1430 Thessaloniki and the Venetian possessions on Kassandra were conquered by the Ottomans. The entire geographic region of Macedonia was under the control of the Ottoman Empire and remained there for almost 500 years until 1912.

Aspirations for autonomy

During the Turkish rule there were joint efforts of the Bulgarians, Serbs and Greeks to break away from the Ottoman Empire . After the liberation of southern Greece and the proclamation of the Greek state in 1829, many Greeks followed the so-called Megali Idea (Greek Μεγάλη Ιδέα "great idea"), which set the goal of liberating the remaining Greek areas from the Ottoman yoke and a Greek state with the capital To create Constantinople . Macedonia, on the other hand, marked the beginning of the Bulgarian National Revival , a period of socio-economic growth and national unification of the Bulgarian people.

In 1864 the geographical region of Macedonia was divided into six administrative districts ( Vilâyet ) of the Ottoman Empire. The vilayets in the geographic region of Macedonia and their respective capitals (in brackets) were Edirne ( Edirne ), Selanik ( Thessaloniki ), Manastır ( Bitola ), Yanya ( Ioannina ), İşkodra ( Shkodra ) and Kosova ( Skopje ). An administrative region of Macedonia or Macedonia existed for the Ottoman Empire neither directly nor indirectly until 1903. From 1903, in the course of the Ottoman and international reform efforts (for example Mürzsteger program ) , the Ottoman Empire spoke of the vilayat-i selase , the three vilayets , which were located in the geographical region of Macedonia. For Bulgaria ended preliminary peace of San Stefano in 1878 Turkish rule. Macedonia, however, was awarded to the Ottoman Empire by the great powers at the Berlin Congress that took place in the same year .

Between 1872 and 1912, tensions built up between the population groups in the geographical region of Macedonia. One area of tension was the school struggle between the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate in Constantinople , the Serbian school authorities and the Bulgarian exarchate . Oswald Spengler remarked on this in 1922 in his work Downfall of the Occident:

“In Macedonia, Serbs, Bulgarians and Greeks founded Christian schools for the anti-Turkish population in the 19th century . If it happened that Serbian was being taught in a village, the next generation consisted of fanatical Serbs. The current strength of the 'nations' is therefore only the result of the earlier school policy. "

In 1893 the Bulgarian freedom movement BMORK (Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committee) was founded in Thessaloniki . After several assassinations, they organized the Ilinden uprising against the Turks in 1903 . The uprising led to the founding of the Kruševo Republic in Macedonia and the Strandscha Republic in Vilayet Edirne , Turkey , both of which only existed for a short time.

Division of the region

In 1912/13 the Balkan Federation ( Kingdom of Serbia , Tsarism Bulgaria , Kingdom of Greece and Kingdom of Montenegro ) waged war against the Ottoman Empire over Macedonia and Thrace (First Balkan War). The Ottoman Empire had to give up most of its European possessions. After that, the dispute over the division of the conquered areas ignited. This led to the Second Balkan War in 1913, from which Bulgaria emerged as a loser.

Most of the historical region of Macedonia then fell to Greece (Greek Macedonia or “Aegean Macedonia” / Macedonia) and Serbia (“ Vardar Macedonia ” / South Serbia). The north-eastern part came to Bulgaria ("Pirin-Macedonia" / Blagoewgrad ) and a small part in the north-west to Albania (Mala Prespa).

During the First World War , the area of today's Macedonia was again attached to Bulgaria. In 1919 Bulgaria lost the conquered territories again and the borders of 1913 were restored. Serbia became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in 1918 ( Kingdom of Yugoslavia from 1929 ). In the Serbian part of the new kingdom, the Slavs of Macedonia were regarded by the authorities as southern Serbs (from 1929 Vardarska banovina ).

The part of Macedonia that fell to Greece was according to a Greek survey in 1913 of 528,000 (44.2%) Greeks , 465,000 (38.9%) Muslims, 104,000 (8.7%) Bulgarians and 98,000 (8.2%) Jews inhabited. During and after the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) there was an exchange of population between Greece and Turkey . 350,000 predominantly Turkish Muslims were expelled from Greece and 565,000 Greek refugees from what is now Turkey , as well as from Constantinople and Smyrna as well as from the Pontos region , were settled. In 1923 the expulsions were subsequently legalized and continued in the Treaty of Lausanne . In addition, 86,000 Bulgarians were resettled from Greece to Bulgaria. As a result, the Greek part of Macedonia is now predominantly populated by Greek people. With the aim of a linguistically homogeneous nation-state , the Hellenization was sought through resettlement and assimilation, sometimes also by force. Slavic place names were replaced by Greek ones, and by the end of the 1940s the maintenance of the Slavic idiom was sometimes made more difficult, with its speakers often subject to reprisals by the state authorities.

In the Second World War , the northern part of Macedonia was again under Bulgarian occupation from 1941, as in the First World War; a small part was occupied by German troops. In 1944 the pre-war borders were restored and the Slavic Macedonians were declared a state people by socialist Yugoslavia .

After the Second World War

The region during the Cold War

In Vardar-Macedonia , a phase of political stability began after recognition as a Yugoslav republic and recognition of a (Slav) Macedonian nation. The same can be assumed for Pirin Macedonia. Despite this “internal” pacification, the region was not free of tension, but on the contrary became one of the first arenas of the Cold War and continued political conflicts, which were once again promoted by nationalist currents and influences. Tito had put forward plans for a united communist Greater Macedonia, either independently or under Yugoslav aegis or as part of a Balkan Union. These plans were not successful; On the one hand, despite communist leadership in both states, an unchanged contrast arose between Bulgaria and Yugoslavia with regard to the view of a nation Macedonia and Slavo Macedonia. The Bulgarian communists denied the existence of such, and Tito explicitly recognized them. Despite the influence of the Comintern headquarters in Moscow until 1948 , an understanding was not possible. The opposition between Bulgaria and Yugoslavia was exacerbated by Yugoslavia's exit from the Comintern in 1948 (Tito's break with Stalin). It is true that Tito gained political room for maneuver as a result, so that he could ignore the 1944 Stalin-Churchill agreement on the Soviet-British spheres of interest in the Balkans. However, it lacked the support of a victorious power and later superpower. The rapprochement between Yugoslavia and the USA that followed the break brought Tito into conflict with the Greek civil war that had been raging since 1946, where the USA became heavily involved in the right-wing Greek government from 1947 onwards.

The Greek civil war began at the end of March 1946. The communist-controlled rebels of the DSE fought against the right-wing central government in Athens, which was supported by Great Britain in 1946 and 1947, and from March 1947 by the USA within the framework of the Truman Doctrine . The Communist Party of Greece had not without internal disputes represented an autonomy or even an independence of the geographical region Macedonia as a political program point (at the same time also Comintern standpoint), which cost it a lot of sympathy in a substantial part of the Greek population. In line with this program, (Slav) Macedonian rebels also fought on the part of the DSE in a separate organization, the NOF, against the Greek central government. The DSE rebels had operational bases and retreat areas in both Yugoslavia and Albania which were not within the immediate range of the Greek armed forces. Even indications from investigative commissions of the United Nations about the support of the DSE from Albania and Yugoslavia were quasi neutralized or even became a point of contention due to the increasingly sharp east-west antagonism in the UN Security Council and the UN General Assembly. Tito's break with Stalin in 1948 ushered in the defeat of the DSE - and thus also the defeat of the NOF - as one of the factors. In 1949 Albania granted the DSE rebels refuge but no active support, so that at the end of September 1949 the DSE was finally subject to the Greek government troops. With that the chances of the NOF to effect a (Slav-) Macedonian autonomy or even independence on Greek territory had passed. As a result of the Greek civil war, both ethnic Greek DSE rebels and ethnic (Slav) Macedonians fled to Yugoslavia, Albania and further into the Eastern Bloc countries. Children were also taken to the Eastern Bloc countries - sometimes with and sometimes without the consent of their parents (deca begalci). In Bitola , Gevgelija and Titov Veles , in particular , considerable communities of Greeks and Slavic Macedonians, some of whom had fled, some of whom were expelled, arose.

Within the SFR Yugoslavia, Macedonia was one of the most economically backward areas, with an economic power of less than 75% of the total Yugoslav average. Agriculture played a major role, especially large-scale tobacco and cotton cultivation. The industry of the resource-poor republic was poorly developed and concentrated primarily on steel and textile products.

In Greece, the consequences of the Second World War and the subsequent civil war for the situation in the administrative regions of Greek Macedonia were considerable. In the 1950s and 1960s, a clear wave of emigration hit the population density, especially in Western Macedonia. The (Slav) Macedonians left Western Macedonia because of the denial of cultural rights and because of the precarious economic conditions. Many ethnic Greeks also emigrated for economic reasons. The post-war Greek governments from 1950 onwards did not accept the existence of a (Slav) Macedonian minority; The exercise of corresponding rights with regard to language, holding public office and possibly schooling was denied, including criminal sanctions. This policy reached a climax in the years of the Greek military dictatorship from 1967 to 1974. In the meantime, however, there were also considerable efforts to ease the tension, such as a treaty on the unbureaucratic small border traffic between northern Greece and the Yugoslav republic of Macedonia. The situation of the (Slav) Macedonian minority has improved since 1974, but human rights organizations still offer enough points of criticism. Recognition by the Greek state has still not taken place; rather, they speak of Slavophonic Greeks .

The Cold War and the iron curtain that ran through the middle of the geographical region of Macedonia had an undeniable stabilizing effect on the potential for conflict in the geographical region. While wars and uprisings repeatedly affected the geographical region until 1950, there has been peace since 1950 at least to the extent that the conflicts were not fought with force of arms. However, the conflicts continued unabated. Bulgaria refused to recognize a (Slav) Macedonian nation, which between 1952 and 1967 led to a sharp diplomatic confrontation with Yugoslavia, which had specifically recognized this (Slav) Macedonian nation. Yugoslavia, on the other hand, tried to attract the (Slav-) Macedonian minority in north-west Greece, which Greece did not see as cultural welfare, but as a preparation for a hegemonic claim to parts of the Greek state with a vanishingly small or no (Slav-) Macedonian minority - especially the territorial claim on the city of Thessaloniki and its surroundings. Greece responded to such possibly expansive ambitions by trying to break the ground on the possible Yugoslavian argumentation: there is no (Slav) Macedonian minority in north-west Greece. The contrast between Bulgaria and Greece, which the (Slav) Macedonian minority in north-west Greece regarded as Bulgarian, was also antagonized with this line of argument.

Recognition of the Macedonian nation in Yugoslavia

The extent to which this recognition as a nation or ethnic group has been a continuous development since the 19th century or a "nation-building" promoted by the Yugoslav head of state Josip Broz Tito is the subject of both historical and political disputes. One point of view emphasizes a continuous development of a Macedonian (or Slav-Macedonian) national consciousness since the 19th century. The Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committee (BMORK for short), which was founded in 1893 and from which the Inner Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (VMRO) emerged in 1919, is seen as an indication of continuous development . They fought against the Ottoman occupation forces by force of arms and sought a Macedonia liberated from the Ottomans. An interim high point of this development found its expression in 1903 in the Ilinden uprising (also Ilinden Preobraschenie uprising): a short-term republic of Kruševo on the territory of today's Republic of North Macedonia is regarded as its historical forerunner state. However, the uprising that took place in the same period also led to the short-lived Strandscha republic in Vilayet Edirne in Eastern Thrace (today southern Bulgaria or European Turkey), which had no effect on the genesis of an approximately "comprehensive" Macedonian nation. The uprising was suppressed by the Ottoman forces in both the west (Kruševo) and the east (Adrianople).

The identification of the Slav-Macedonians before 1900 is also made more difficult by the fact that supposedly neutral sources such as travelogues summarized the Slavic population as a group (compare Ami Boué , who in his travelogue La Turquie d'Europe from 1840 all Slavs in Bulgaria, " Moesiens ", Macedonia and Thrace called Bulgarians). Alternatively, the Ottoman perspective came into play, which until 1876 differentiated according to religion (and thus subsumed Slavic and Greek Orthodox in one category) and after 1876 only differentiated between Bulgarian Orthodox and Greek Orthodox Christians. A (Slav) Macedonian Orthodox Church , which was only to be founded in 1967 as a result of the nation building under Tito's direction, was not available as a distinguishing feature at the time.

In the course of the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913, the Macedonian (i.e. Slav-Macedonian) national consciousness and the demand for an independent state or extensive autonomy were not taken into account. However, part of the population took part in the wars through the Macedonian-Adrianople Landwehr of the Bulgarian armed forces and thus expressed solidarity with the Bulgarian side. During the First World War , after the defeat of Serbia in 1915, Bulgarian troops occupied what is now the Republic of Macedonia, before they expanded their attacks in 1916 to what is now the Greek administrative region of Western Macedonia and briefly occupied the area of what is now the Florina region . In the peace treaties after the First World War, the division of the geographical region of Macedonia after the Balkan Wars was confirmed as the status quo, despite further claims by all parties involved. Again, a (Slav) Macedonian national consciousness was not taken into account.

In the interwar period up to the outbreak of the Second World War in the Balkans in April 1941, the states that had divided up the geographic region of Macedonia pursued a policy of assimilation. In Vardar Macedonia, which was then known as Vardarska Banovina , the possible existence of a Macedonian (Slav-Macedonian) ethnic group was denied by the term “southern Serbs” and at the same time assimilation was promoted. A no less assimilative policy was pursued in Aegean Macedonia, which had belonged to Greek territory since 1913. Renaming of localities to partly previously common Greek names (Edessa), partly to previously non-existent Greek names (Ptolemaida) were used in addition to the designation of the Slavic-speaking part of the population as Slavophone Greeks to deny an ethnic or minority problem. The small Bulgarian part of the Macedonia geographic region, Pirin-Macedonia, has been referred to as Bulgarian. At that time there was no official mention of a (Slav) Macedonian nation. Rather, political and territorial claims by the various neighboring states circulated partly out of economic, partly out of ethnic-national motivation. However, one economic and geostrategic argument prevailed: Serbia needed access to the Aegean Sea (Thessaloniki), as did Bulgaria; Greece did not want to give up this access. There was no discussion of minority concerns or ethnic issues in any of the states. It was therefore only logical that a rejection of nationalist or sometimes imperialist demands was not to be expected. Until the outbreak of the Second World War, there were no attempts by the state to promote extensive autonomy or an independent state with (Slav) Macedonian identity on the soil of Vardar Macedonia.

The outbreak of World War II in the Balkans, which can be dated to the German attack from Bulgaria on Greece and Yugoslavia on April 6, 1941, changed the situation significantly. Bulgaria occupied Vardar Macedonia with German permission. Access to Aegean Macedonia was very limited: the Germans reserved the occupation of what is now the Greek administrative regions of Western and Central Macedonia, including the city of Thessaloniki and a border strip with Turkey that also included the port of Alexandroupolis. The Bulgarian occupying power pursued an assimilation policy in line with Bulgarization .

The genesis of an independent Slavic nation on the soil of the former Vardar Macedonia is closely connected with the establishment of the second socialist and federal Yugoslavia after the Second World War. The Yugoslav communist leader Tito promoted active resistance against the Bulgarian occupation regime from 1943 under the slogan of a Slav-Macedonian or Macedonian resistance against the Bulgarian occupation. In what is now Greek territory, the inhabitants belonging to the Slav-Macedonian minority behaved partly passively, partly they joined the Greek resistance, partly (but only in a minority) they collaborated with the occupying forces of the Axis powers. With the German withdrawal from Greece and Yugoslavia in October / November 1944 and the simultaneous collapse of the Bulgarian occupation in Vardar-Macedonia, the representatives of the Slav-Macedonian or Macedonian resistance gained the upper hand. A British liaison officer described the (Slav) Macedonian resistance as follows:

“The Macedonian partisan movement is primarily nationalist and secondarily communist. In their propaganda they always emphasize Macedonian national independence. "

Consequently, in 1946 the Vardar-Macedonia region became a part of the Yugoslav federal state as the Socialist Republic of Macedonia (SR Makedonija) , in accordance with the plans of the 2nd AVNOJ Conference in Jajce in 1943 . However, representatives of the Macedonian communists were absent from this decision. The Slavic Macedonians were also recognized as an independent nation. As part of this recognition as a nation, a reform of the Macedonian language was commissioned. This has been standardized on the basis of vardar-Macedonian Slavic dialects, by a decision of the AVNOJ the official language proclaimed Macedonia and subsequently to a fully functioning, Serbian-oriented standard language developed . The first standardized grammar of the Macedonian literary language by Blaže Koneski followed .

An autocephalous Macedonian Orthodox Church was founded in 1958, against the resistance of the Greek Orthodox and Serbian Orthodox Churches . In 1967 the Russian Orthodox Church recognized the Macedonian Orthodox Church as autocephalous.

The region after the disintegration of Yugoslavia (1990 to today)

Independence of the Republic of Macedonia

Although relations between Greece and the SFR Yugoslavia were not the worst, the majority in Greece were indifferent to their northern neighbors. This changed when, already during the breakup process of Yugoslavia, Slavic-Macedonian nationalists increasingly put into circulation maps showing the Greek or Aegean Macedonia ( Macedonia ), which belongs to the Greek state, and the Bulgarian Pirin Macedonia ( Blagoewgrad ) , the Yugoslavian one or Vardar Macedonia (southern Serbia) were struck.

With the break-up of Yugoslavia , the former Republic of Macedonia proclaimed independence as the Republic of Macedonia on November 19, 1991 ; In 1993 it was accepted into the United Nations , at the insistence of Greece as the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (English Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia ).

The name question

Greece saw it as a provocation that Macedonia presented a national flag when it declared independence in 1991, on which the star of Vergina, discovered in 1978 in the northern Greek city of Vergina during excavations, could be seen. Greece feared threats to the integrity of its territory, especially after Macedonia, in the preamble of its new constitution , invoked the tradition of the Republic of Kruševo , which provided for a unified state within the boundaries of geographical Macedonia. Greece refuses to use the name Macedonia for its northern neighbors because it fears the conquest and Slav monopoly of Macedonian history.

Athens responded immediately to this provocation by closing its border crossings and boycotting it, as well as closing the port of Thessaloniki, through which the Republic of Macedonia handled 80% of its imports in 1991. The boycott, which plunged Macedonia into a dramatic economic crisis, was lifted in 1994 after the government in Skopje agreed to change the flag. Subsequently, economic and political cooperation between the Republic of Macedonia and Greece developed well. The question of the name remained and remains mostly excluded from political discussions.

The two states agreed on a solution to the dispute in the Prespes Agreement in 2018 . In February 2019, the Republic of Macedonia changed its name to the Republic of North Macedonia in accordance with the agreement , after both parliaments had approved the agreement between the two states at the end of January 2018.

Ethnic conflicts in the Republic of Macedonia (2000)

From 2000 the Republic of Macedonia was rocked by violent unrest. Comparable to the downright “patchwork” in ethnic terms in other parts of Macedonia and the Balkans, conflicts broke out there, to a limited extent also with armed violence, between the Albanian minority and the Macedonian majority. On the Macedonian side, fears of a Greater Albania including Kosovo and north-western parts of the Republic of Macedonia were voiced, also under the influence of the Kosovo conflict of 1999 that occurred in the immediate vicinity. In addition to the numerically very strong Albanian minority, a small Serbian minority also made itself felt. The nationality conflicts in the historical region of Macedonia had also "caught up with the Republic of Macedonia" in 2000. The Ohrid Framework Agreement was signed on August 13, 2001 through the mediation of the EU. Through this agreement and its implementation, the ethnic differences between Albanians and Macedonians in the Republic of Macedonia were noticeably defused.

population

In the Republic of North Macedonia, Slavic Macedonians make up the majority of the population. There are also minorities, Albanians , Serbs and Turks .

The Greek “geographical region” ( geografikó diamérisma / γεωγραφικό διαμέρισμα) Macedonia is administratively divided into three administrative regions, the eastern also including western Thrace. In contrast to other regions, this one has a strong identity, based on the one hand on historical differences, on the other hand it goes back to the competition between Thessaloniki and Athens . Politicians from this region are said to have typically “Macedonian” characteristics.

The vast majority of the population of the region is Greek-Macedonian , with a large part of the Pontic Greeks taking the place of the formerly non-Greek population in the 1920s . However, there is a small Slavo Macedonian (or Slavophone) minority, especially in the prefectures of Kilkis and Florina . Their share in the total population is not certain, as the Greek state does not collect any figures on the linguistic or ethnic origin of the inhabitants in censuses. Furthermore, there are Aromanian , Megleno-Romanian and Armenian parts of the population, which, however, are largely assimilated and whose languages are now considered threatened.

Bulgaria immediately recognized the Republic of Macedonia as a state, but refused for years to recognize a Macedonian minority in its own country and Macedonian as its own language. In 1999, the Bulgarian and Macedonian Governments resolved their longstanding linguistic dispute that was putting a heavy strain on bilateral relations. Bulgaria officially recognized the independence of the Macedonian language and minority for the first time. In return, Macedonia renounced any influence on the Slavic-Macedonian minority in the Bulgarian part of the region.

Macedonian culture

Macedonia is not an independent cultural area. Above all, this is due to the different ethnic groups, each of which "lives" its own culture and forms independent cultural areas. Religion also plays a role, as the population is divided into followers of Orthodox Christianity and Islam. But in many places there is a kind of cultural synthesis through which the cultures have partly mixed or influenced one another.

literature

The basis of the Macedonian written language in today's Republic of North Macedonia was the Central Macedonian dialects in the late 19th century. The evidence of folk poetry comes mainly from Western Macedonia. Since 1926, a monthly literary magazine ( Mesečni pregled , later Južni pregled ) appeared in Skopje , edited by Petar Mitropan and enjoyed a good reputation throughout Yugoslavia. It offered one of the very few publication options in the otherwise marginalized Macedonian language. In December 1939 it was discontinued - possibly due to lack of money.

The philologist, poet and editor of the literary magazines Nov den and Makedonski jazik , Blaže Koneski (1921–1993) made the greatest contribution to the codification of the Macedonian language, which was approved as the state language since 1945 . First, a prose language had to be found that no longer formally imitated the folk song. The first authors included Vlado Maleski , Gogo Ivanovski and Jovan Boškovski . Taško Georgievski went into exile in Yugoslavia after the Greek civil war in 1947 and wrote the novel The Black Saat (German 1974) about the persecution of the Macedonian revolutionaries in Greece.

One of the most important figures in young Macedonian literature was the versatile author Slavko Janevski . He wrote the first novel in Macedonian, Seloto zad sedumte jaseni . However, notable literature has only existed since the 1960s. The Second World War remained a frequent topic until the 1990s. Živko Čingo (1935 or 1936–1987) questioned the socialist realism's conception of man in his stories and satires.

The German translator Matthias Bronisch published two representative anthologies of Macedonian literature in the 1970s.

music

The rich folk music of Macedonia shows influences from Bulgaria, Serbia and Turkey (in the southeast) and Greece (in the south). The Roma -Music has always been an essential part of the Macedonian music. The Roma singer Esma Redžepova and Marem Aliev , who now lives in Switzerland, became internationally known with his Aliev Bleh Orkestar .

See also

literature

- Otto Hoffmann: The Macedonians, their language and their nationality. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1906.

-

NGL Hammond , FW Walbank : A History of Macedonia , 3 volumes, Oxford 1972-88.

- Volume 1: Historical Geography and Prehistory (1972)

- Volume 2: 550-336 BC (1979)

- Volume 3: 336-167 BC (1988)

- MB Sakellariou: Macedonia: 4000 Years of Greek History and Civilization. Athens 1983.

- Malcolm Errington: History of Macedonia. CH Beck, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-406-31412-0 .

- Giannēs Turatsoglu: Macedonia - History, Monuments and Museums. Ekdotike Athenon, Athens 1995, 1997, ISBN 960-213-329-5 .

- Stella G. Miller: Macedonians. In: Kathryn A. Bard (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0 , pp. 460-64.

- Adamantios Skordos: Greece's Macedonian Question. Civil War and History Politics in Southeast Europe 1945–1992. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2012, ISBN 3-8353-0936-6 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ John Breuilly (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of the History of Nationalism , Oxford University Press, 2013, ISBN 0-19-920919-7 , S. 192. Quote: The ancient name, Macedonia 'disappeared during the period of Ottoman rule and was only restored in the nineteenth century originally as geographical term. (engl.)

- ↑ In the introduction to the discussion, see Peter van Nuffelen: Are the Macedonians Greeks? About nationalism and the history of research. In: Martin Lindner (Ed.): Antikenrezeption 2013 n. Chr. , Heidelberg 2013, pp. 89–106.

- ↑ Diodorus 18.60.

- ^ Jan Henrik Holst: Armenian Studies . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-447-06117-9 , pp. 65 ( excerpt [accessed February 21, 2018]).

- ^ Nicholas GL Hammond, Guy T. Griffith: A History of Macedonia . tape 2 . Oxford 1979, p. 3, 11, 60 .

- ↑ Isocrates: Speech to Philip 105-108; see Hilmar Kehl: The monarchy in the political thinking of Isokrates. Bonn 1962, pp. 97-104; Klaus Bringmann: Studies on the political ideas of Isocrates. Göttingen 1965, pp. 96-102.

- ↑ Kehl (1962) pp. 97f.

- ↑ Venceslas Kruta: Les Celtes, histoire et dictionnaire , S. 493rd

- ↑ Cf. Frank Daubner : Macedonia after the Kings (168 BC - 14 AD) , Stuttgart 2018.

- ↑ Cf. Max Vasmer : The Slavs in Greece. Berlin 1941 (= treatises of the Prussian Academy of Sciences, born 1941, Philosophical-Historical Class, No. 12).

- ^ J. Fine: The Early Medieval Balkans. The University of Michigan Press, 1983, ISBN 0-472-10025-4 .

- ↑ Max Vasmer : The Slavs in Greece , p. 176.

- ↑ That was the work of the Slav apostles Kyrillos and Methodios and their students from Thessaloniki (Slavic Solun ) . Cyril created the Glagolitic alphabet and not, as is often claimed, the Cyrillic . The "Glagoliza" was used parallel to the "Kyrillica" until the 13th century. The origin of the "Kyrillica" is controversial. Some researchers see their creation through Clemens (Kliment) of Ohrid , others in the school of Preslaw in north-east Bulgaria. However, it is certain that the Cyrillic alphabet originated in Bulgaria in the 9th or 10th century . Most of the letters were adopted or derived from the Greek alphabet (in its Byzantine writing). For sounds that did not appear in Greek , characters from the Glagolitic script ( Glagoliza ) were adopted or reformed.

- ↑ a b c Fikret Adanir: The Macedonian Question. Their origin and development up to 1908. Frankfurter Historische Abhandlungen, Volume 20. Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden 1979, ISBN 3-515-02914-1 , p. 16.

- ^ Nina Janich, Albrecht Greule: Language cultures in Europe: an international handbook. Gunter Narr Verlag, 2002, p. 29.

- ↑ a b Fikret Adanir: The Macedonian Question. Their origin and development up to 1908. Frankfurter Historische Abhandlungen, Volume 20. Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden 1979, ISBN 3-515-02914-1 , p. 2.

- ↑ Fikret Adanir: The Macedonian Question. Their origin and development up to 1908. Frankfurter Historische Abhandlungen, Volume 20. Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden 1979, ISBN 3-515-02914-1 , p. 3.

- ↑ Quoted from: Stefan Troebst : Macedonian answers to the “Macedonian question”: Nationalism, founding a republic and nation-building in Vardar-Macedonia. 1944-1992. In: Georg Brunner, Hans Lemberg: Ethnic groups in East Central and South Europe. Southeastern European Studies, Volume 52. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 1994, ISBN 3-7890-3095-3 , p. 213.

- ↑ Katrin Boeckh: From the Balkan Wars to the First World War. Small State Policy and Ethnic Self-Determination in the Balkans. R. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 1996, also dissertation, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich 1994/95, ISBN 3-486-56173-1 , p. 227.

- ↑ a b c d e Hugh Poulton: Who are the Macedonians? C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 1-85065-534-0 , pp. 53, 163.

- ↑ Hinrich-Matthias Geck: The Greek labor migration: An analysis of its causes and effects. Hanstein, 1979, ISBN 3-7756-6932-9 , p. 101.

- ^ Iakovos D. Michailidis: On the other side of the river: the defeated Slavophones and Greek History. In: Jane K. Cowan (Ed.): Macedonia. The Politics of Identity and Difference. Pluto Press, 2000, ISBN 0-7453-1589-5 , pp. 68 ff.

- ^ Riki van Boeschoten: When difference matters: Sociopolitical dimensions of ethnicity in the district of Florina. In: Jane K. Cowan (Ed.): Macedonia. The Politics of Identity and Difference. Pluto Press, 2000, ISBN 0-7453-1589-5 , p. 1 ff.

- ^ Richard Clogg (Ed.): Minorities in Greece: Aspects of a Plural Society. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2002, ISBN 1-85065-706-8 .

- ^ Loring M. Danforth: The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1995, ISBN 0-691-04357-4 .

- ↑ a b Stefan Troebst: Macedonian answers to the “Macedonian question”: Nationalism, founding a republic and nation-building in Vardar-Macedonia. 1944-1992. In: Georg Brunner, Hans Lemberg: Ethnic groups in East Central and South Europe. Südosteuropa-Studien, Volume 52.Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 1994, ISBN 3-7890-3095-3 , p. 203.

- ↑ Stefan Troebst: Macedonian answers to the "Macedonian question": Nationalism, founding a republic and nation-building in Vardar-Macedonia. 1944-1992. In: Georg Brunner, Hans Lemberg: Ethnic groups in East Central and South Europe. Southeast European Studies, Volume 52. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 1994, ISBN 3-7890-3095-3 , p. 204.

- ↑ Ami Boué: La Turquie d'Europe. Tome Deuzième (Volume 2). Arthus-Bertrand, Paris 1840, p. 5.

- ↑ Foreign Office: Files on German Foreign Policy, 1918–1945. Self-published, 1995, p. 585.

- ^ Heinz Willemsen, Stefan Troebst: Schüttere continuities, multiple breaks; The Republic of Macedonia 1987–1995. In Egbert Jahn (Ed.): Nationalism in late and post-communist Europe, Volume 2: Nationalism in the nation states. Verlag Nomos, 2009, ISBN 978-3-8329-3921-2 , p. 517.

- ↑ Quoted from: Stefan Troebst: Macedonian answers to the “Macedonian question”: Nationalism, republic foundation and nation-building in Vardar-Macedonia. 1944-1992. In: Georg Brunner, Hans Lemberg: Ethnic groups in East Central and South Europe. Southeastern Europe Studies, Volume 52. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 1994, ISBN 3-7890-3095-3 , p. 207.

- ↑ a b Stefan Troebst: Macedonian answers to the “Macedonian question”: Nationalism, founding a republic and nation-building in Vardar-Macedonia. 1944-1992. In: Georg Brunner, Hans Lemberg: Ethnic groups in East Central and South Europe. Southeast European Studies, Volume 52.Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 1994, ISBN 3-7890-3095-3 , p. 210.

- ↑ Wolf Oschlies : Textbook of the Macedonian Language: in 50 lessons. Verlag Sagner, Munich, 2007, ISBN 978-3-87690-983-7 , p. 9: “[…] the resolution of the ASNOM (Antifascist Council of the People's Liberation of Macedonia), which was issued on August 2, 1944 in the southern Serbian (or northern Macedonian ) Monastery of Sv. Prohor Pćinjski proclaimed the Republic of Mekedonia (within the Yugoslav Federation) and the Macedonian vernacular as the official language. "

- ^ The Making of the Macedonian Alphabet

- ↑ Ljubčo Georgievski : With the face to the truth. Selected articles, essays and lectures (Bulgarian С лице към истината. Избрани статии, есета, речи), Sofia 2007, ISBN 978-954-9446-46-3 .

- ↑ a b Stefan Troebst: Macedonian answers to the “Macedonian question”: Nationalism, founding a republic and nation-building in Vardar-Macedonia. 1944-1992. In: Georg Brunner, Hans Lemberg: Ethnic groups in East Central and South Europe. Südosteuropa-Studien, Volume 52. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 1994, ISBN 3-7890-3095-3 , p. 211.

- ↑ Foreign Office: Greece - Foreign and Security Policy

- ↑ Macedonia is now officially called North Macedonia. Spiegel Online, February 12, 2019, accessed August 2, 2019.

- ^ Greeks (Pontus). In: Encyclopedia of the European East. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015 ; accessed on March 4, 2015 .

- ↑ Aleksandr D. Dulienko: Aegean-Macedonian. In: Miloš Okuka (Ed.): Lexicon of the Languages of the European East . Klagenfurt 2002 ( PDF; 174 KB ( Memento from April 11, 2016 on WebCite ))

- ^ Peter M. Hill: Macedonian. In: Miloš Okuka (Ed.): Lexicon of the Languages of the European East . Klagenfurt 2002 ( PDF; 462 KB ( Memento from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ))

- ^ Petar Atanasov: Aromanian. In: Miloš Okuka (Ed.): Lexicon of the Languages of the European East . Klagenfurt 2002 ( PDF ( Memento from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), 197 kB)

- ^ Petar Atanasov: Megleno-Romanian. In: Miloš Okuka (Ed.): Lexicon of the Languages of the European East . Klagenfurt 2002 ( PDF ( Memento from March 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), 190 kB)

- ↑ Susanne Schwalgin: “We will never forget!” Trauma, memory and identity in the Armenian diaspora in Greece. Bielefeld 2004, ISBN 3-89942-228-7 .

- ↑ Christoph Pan: The minority rights in Greece. In: Christoph Pan and Beate Sibylle Pfeil: Minority Rights in Europe , Second revised and updated edition. (Handbook of European Ethnic Groups, Volume 2), Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-211-35307-0 .

- ^ Herbert Küpper: Protection of minorities in Eastern Europe - Bulgaria. (PDF; 833 kB) Archived from the original on January 31, 2012 ; accessed on March 4, 2015 .

- ↑ Nada Boškovska: The Yugoslav Macedonia 1918-1941: A border region between repression and integration. Vienna 2009, p. 324.

- ↑ Macedonia. (= Modern Storytellers of the World, Vol. 53), Erdmann Verlag, Tübingen / Basel 1976 (23 stories); Modern Macedonian poetry. Erdmann Verlag, Tübingen / Basel 1978.