Albanians in North Macedonia

The Albanians in northern Macedonia ( Albanian Shqiptarët në Maqedoninë e Veriut , Macedonian Албанци во Северна Македонија Albanci vo Severna Makedonija ) form the largest ethnic minority in the country and put in 13 (including two districts in the capital Skopje ) of 81 Opštini over half the population . According to the last census in the country in 2002, their number is given as 509,083 people, which is 25.17 percent of the total population. However, some Albanian parties, organizations, associations and non-governmental organizations estimate the number of the Albanian ethnic group to be much higher.

The Albanians are an autochthonous population in North Macedonia and have lived side by side with (Slavic) Macedonians , Turks , Roma and Serbs for centuries . After the fall of the Ottoman Empire at the beginning of the 20th century, the Albanian-inhabited areas of what is now North Macedonia came to the Kingdom of Serbia . The motherland Albania thus only comprised about half of the region of the Balkans inhabited by Albanians .

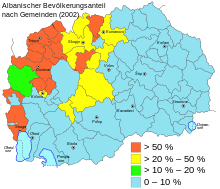

Geographical distribution

The Albanians of North Macedonia live mainly in the western part of the country. Their settlement area is part of the closed Albanian language area on the Balkan Peninsula, but is also partially populated by other ethnic groups . Since 1912 this settlement area has been separated from Albania and Kosovo by borders .

The Albanian population of the country lives in particular on Lake Ohrid , in the Black Drin valley , on the upper course of the Vardar and in the Kumanovo basin . Further settlement areas are the Bitola plain and some areas in the western hill country of North Macedonia between Bitola and Skopje, but here the Albanians usually form a minority in the total population.

| 100-50% | 50-20% | <20% (selection) |

|---|---|---|

| Lipkovo | Kumanovo | Ilinden |

| Studeničani | Petrovec | Veles |

| Aračinovo | Zelenikovo | Gradsko |

| Tearce | Skopje | Drugovo |

| Tetovo | Čučer-Sandevo | Centar Župa |

| Želino | Sopište | Debarca |

| Brvenica | Jegunovce | Ohrid |

| Bogovinje | Čaška | Demir Hisar |

| Vrapčište | Dolneni | Resen |

| Gostivar | Kruševo | Bitola |

| Oslomej | Kičevo | Mavrovo and Rostuša |

| Zajas | ||

| Debar | ||

| Struga |

- The municipalities in Kursiv were merged with the municipality of Kičevo in 2013.

Demographic behavior

| 1948 | 1953 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 1994 | 2002 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macedonians | 68.5 | 66 | 71.2 | 69.3 | 67 | 65.3 | 66.6 | 64.18 |

| Albanians | 17.1 | 12.4 | 13 | 17th | 19.8 | 21.7 | 22.7 | 25.17 |

As can be seen in the table, the proportion of Albanians experienced an extremely deep "fall" between 1948 and 1953. Accordingly, it fell from 17.1 to 12.4 percent. This is mainly due to the fact that in the 1953 census many classified themselves as Turks in order to be able to emigrate to Turkey . Because of this, on the other hand, the proportion of the Turkish population rose from 8.3% (1948) to 15.6% (1953).

The data from 1991 should also be noted. The census carried out in Yugoslavia at that time was boycotted by the majority of the Albanian population of Yugoslavia. This information is therefore based on data from population registers and updates.

history

- For the history up to 1912 see History of Albania and Macedonia , for the subsequent events see also History of North Macedonia

Separation from Albania - part of Serbia (Yugoslavia)

In December 1912, shortly after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire by the Balkan Federation in the Balkan Wars , ambassadors from the great powers of the time ( Great Britain , Germany , Russia , Austria-Hungary , France and Italy ) met in London to clarify the remaining questions of the conflict. The London Ambassadors Conference recognized an independent Albanian state because of the support of Austria-Hungary and Italy . However, the borders of the new state did not include large areas of the Albanian settlement area. A large part of the Albanian settlement area fell to the Kingdom of Serbia , including those in the Vardarska banovina (Serbian part of the historical region of Macedonia ), which later became roughly the Socialist Republic of Macedonia .

Post-war period - socialist Yugoslavia

When the Socialist Republic of Macedonia was proclaimed in 1946, its communist constitution guaranteed minorities the right to cultural development and the free use of their language. The construction of schools for the minorities began immediately in order to reduce their high illiteracy rate. In the following two decades, measures were continuously introduced to integrate the Albanian ethnic group into the economic and social life of the new socialist state and to improve its social opportunities. Since the end of the Second World War, the country's population has increased steadily. Between 1953 and 2002, the Albanian-speaking population also grew by 31.3 percent.

Disintegration of Yugoslavia - social tensions between the ethnic groups

In the late 1980s, when the province of Kosovo was stripped of its autonomy by Yugoslavia and the oppression of the Albanian ethnic group increased, similar developments also took place in the Republic of Macedonia. This assimilation policy was also made clear with the constitutional amendment of 1990: Macedonia was redefined as a state of the Macedonian people and the Albanian and Turkish nationalities to a national state of the Macedonian people .

On September 8, 1991, Macedonia declared itself the fourth republic of Yugoslavia (after Slovenia , Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina ) to be independent and free parliamentary elections were held for the first time. The democratization process was thus initiated. Macedonia was the only republic to leave the socialist Federal Republic without Belgrade resistance. In contrast to Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina , there was no war in Macedonia.

In January 1992 Albanians organized a referendum on territorial autonomy in Struga, southwest Macedonia . The Macedonian government declared the project to be illegal on the grounds that this project was secessionary . The Council of Albanian Political Parties in the Former Yugoslavia decided that autonomy would be the last option for the Albanians in the Republic of Macedonia if all other democratic efforts failed. This declaration of autonomy by the "Republic of Ilirida" is not supported by all political parties of the Albanians in Macedonia, rather it was a symbolic act.

The grievances of the ethnic minorities grew steadily. In February 2001, the open hostilities finally escalated into civil war-like conditions . The uprising was led by the National Liberation Army ( Albanian Ushtria Çlirimtare Kombëtare , UÇK for short ) in the north-west and north of the country on the border with Kosovo and Serbia . An armistice was agreed in July 2001 with international mediation. The Ohrid Framework Agreement was intended to ensure adequate representation of the Albanian minority in politics and administration and to disarm the National Liberation Army. An integral part of the agreement is, for example, equating the Albanian language with the Macedonian language in communities where Albanians make up over 20 percent of the population.

The agreement was more or less implemented by the following governments (including VMRO-DPMNE ), but fundamental questions remained open and social equality with the (Slavic) Macedonian people has not yet been achieved. Again and again, nationalistically motivated conflicts flare up - on both sides, especially among young people.

Social situation

Large parts of the Albanian population in North Macedonia have emigrated regularly in the past . In addition to economic reasons, there were also political and religious motives. The first destination in the early 20th century was usually Turkey , where the emigrants found more religious freedom. Many already spoke the Turkish language and were mostly familiar with the local culture, which was not particularly different from theirs. After the Second World War, the aims of the emigrants changed, and now Western and Central Europe and the United States were host countries for people looking for work; but also in southern and northern Europe and in Australia numerous, albeit smaller, immigrant communities emerged. When they arrived in the New World, the Albanians initially did menial work in construction , mines , factories , agriculture and cattle breeding, as well as in the catering trade . The low level of education and the lack of financial resources prevented the immigrants from improving their living conditions. The xenophobia encountered there and the lack of command of the new language made the emigrants difficult to cope with.

From the late 1980s, the political and legal situation of the Albanians in all of Yugoslavia deteriorated noticeably. Discrimination in the world of work increased, rights and freedoms were severely restricted, and the number of violent attacks on both sides (Albanians and Macedonians) rose rapidly. As a result of this minority policy pursued by the Macedonian government, tensions between the peoples within Macedonia intensified and nationalism strengthened everywhere . In 2001 there was an uprising by Albanian irregulars . After several months of fighting between Albanian guerrilla fighters and the Macedonian police or army , a framework agreement was agreed in the city of Ohrid in August of the same year . The most important representatives of both sides, as well as foreign envoys, came together and signed the treaty, which, in addition to disarming the Ushtria Çlirimtare Kombëtare (UÇK), also included safeguarding the minority rights of the Albanians. Today's Democratic Union for Integration (BDI) party emerged from the UÇK after 2001 and is considered to be the strongest party among the Albanians. Since then it has been part of governments (especially VMRO-DPMNE ) several times and has been able to provide ministers. But the Albanian Democratic Party (PDSH) also formed governments - mostly with the Social Democrats . The Albanian parties set themselves the core task of implementing the agreement, which has largely been successful. However, the successes are constantly overshadowed by criminal incidents on both sides. Extreme nationalists from both peoples have set themselves the goal of destroying the "hostile" ethnic group and their cultural assets and are constantly organizing acts of sabotage and attacks on mosques and Tekken or churches and monasteries. This increases the tensions between the ethnic groups, and as a reaction, citizens gather for demonstrations that are partly peaceful and partly violent.

The government in Skopje is mostly passive with regard to the domestic political situation and constantly mentions the Ohrid Framework Agreement, which all ethnic groups should remember. Official Albanian authorities also urge peace and order and the cultivation of inter-ethnic relationships.

The Albanians in North Macedonia maintain economic and cultural ties with Albania and Kosovo.

politics

The party landscape of the Albanian minority of North Macedonia is fragmented into many small political parties . Two more specific in the past and up to the present time in the political events of the minority: the Established in 1997, Democratic Party of Albanians (PDSH) and founded in 2001, as a successor to the KLA formed Democratic Union for Integration (BDI). Other newer parties are the New Democracy (DR) from 2008 and above all the National Democratic Rebirth (RDK) from 2011. Until 2008, the Party for Democratic Prosperity also played a central role in the politics of the Albanians in Macedonia. The distribution of seats for the Albanian parties in the parliament of North Macedonia ( Macedonian Собрание , Sobranie ; Albanian Kuvend / -i ) was as follows in the elections of 2011 , 2014 and 2016:

| Political party | acronym | Parliament seats 2011 from 123 |

Percentage 2011 |

Parliament seats 2014 from 123 |

Parliament seats 2016 from 120 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic Union for Integration | BDI | 15th | 12.20% | 19th | 10 |

| Albanian Democratic Party | PDSH | 8th | 6.50% | 7th | 2 |

| National Democratic Rebirth | RDK | 2 | 1.63% | - | |

| Movement besa | - | - | - | 5 | |

| Albanian Alliance | - | - | - | 3 | |

| Independent candidates | - | - | 1 | ||

| All in all | 25 of 123 | 20.33% | 27 | 20th | |

Among the most important non-parliamentary political movements of the Albanian minority that counts citizens' movement Zgjohu! ("Wake up!").

Culture

Culturally , the Albanians of North Macedonia are linked to Albania and Kosovo in the Albanosphere . The common flag , the national anthem , the common history, the national folk songs, the common language and much more are among the connecting factors.

Education in Albanian takes place at all levels, including in the Tetovo State University , which has been established in 1994 and has been in existence since 2004 . The South East European University has also offered classes in Albanian since it was founded in 2001. The city of Tetovo also plays a central role in the country for the Albanian population: most of the political parties, many non-governmental organizations and companies as well as national associations have their headquarters here.

The culture of the Albanians was influenced by the Ottoman influence, as in Albania and Kosovo, also by Serbian and Bulgarian / Macedonian elements. Conversely, however, elements of the Albanian culture also flowed into the named peoples. This symbiotic coexistence with the other nations made the Albanians of North Macedonia more independent from the cultures of Albania and Kosovo.

The main media of the Albanian minority in North Macedonia are the private broadcaster Alsat-M , the daily newspaper Zhurnal , the daily newspaper Koha , and the Albanian channel MRT Sat2 of Makedonska Radio-Televizija .

language

The native language of the Albanians Nordmazedoniens is the Indo-European part of Albanian language , which applies in municipalities with more than 20 percent of the population Albanians as second official language. The Macedonian and Turkish are fluent by some segments of the population, including from those in ethnically mixed towns and villages. In addition to the official language Macedonian, English and French are also taught at the school.

The southwest Macedonian city of Bitola (Monastir; alb. Manastir ) plays an important role in the history of the Albanian language . In 1908, the Congress of Monastir took place there from November 14th to 22nd , which established the uniform use of the Albanian written language with the rules that still apply today. The participants agreed on a strictly phonetic spelling with only two special characters ( Ç / ç [ ʧ ] and Ë / ë [ ə ] ).

Albanian has two dialects , the two language areas of which border in the south-west of North Macedonia. These regional dialects are described in more detail in the following two sections.

Gegisch

The majority of Albanians in North Macedonia speak Gegic varieties of the Albanian language, some of which are very different from one another. The Geisch-speaking area of North Macedonia is linguistically (mostly) divided into two zones: the northern larger (called "Northeast Gegisch") includes the regions of Kumanovo (alb. Kumanova ), Skopje ( Shkup ), Tetovo ( Tetova ), Gostivar and Kičevo ( Kërçova ). The southern smaller zone (called "Central Gegisch") includes Debar ( Dibra ) and Struga ( for the various dialects of Albanian see here ).

Tuskish

In the region of Lake Ohrid and Lake Prespa and in the vicinity of the cities of Bitola , Kruševo and Dolneni there are also some villages where Tuscan dialects are spoken. At Lake Ohrid these are Frangovo (alb. Frëngova ), Kališta ( Kalisht ), Radolišta ( Ladorisht ), Zagračani ( Zagraçan ) and partly also in Dolna Belica ( Belica e Poshtme ) and as an immigrant language in the cities of Struga and Ohrid ( Ohër ). On Lake Prespa these are the villages Arvati , Asamati , Gorna Bela Crkva ( Kisha e Bardhë e Siperme ) Grnari ( Gërnar ) Dolna Bela Crkva ( Kisha e Bardhë e Poshtme ), Kozjak , Krani ( crane ), Nakolec , Sopotsko ( Sopocka ) and the city of Resen ( Resnja ). In the Bitola ( Manastir ) region there are the villages of Trnovo ( Tërnova ), Nižepole ( Nizhepola ) and Bratin Dol ( Bratin Doll ) as well as a very small minority in the city itself. A large Tuscan-Albanian minority (around 20 percent of the total population) also lives in the municipality of Kruševo ( Krusheva ). The villages with a majority Albanian population include Aldanci ( Alladinc ), Belušino ( Bellushina ), Borino ( Borina ), Jakrenovo ( Jakrenova ), Norovo ( Norova ), Presil ( Presill ) and Saždevo ( Sazhdeva ). In the municipality of Dolneni ( Dollnen ) six villages have Albanian inhabitants, but only in Crnilište ( Cënilisht ) and Žitoše ( Zhitoshja ) they make up the vast majority. From a linguistic point of view, all Tuscan varieties within North Macedonia belong to “North Tuscan” ( see here for the various dialects of Albanian ).

religion

In contrast to the Albanians in Albania and Kosovo, the Albanians in North Macedonia belong almost exclusively to Islam . As Sunnis they profess the Koran and the Sunna (tradition of the Prophet Mohammed ); usually the law school of true Hanafi . In recent years, the Wahhabi and Salafist beliefs have also spread to a small extent . In contrast to Albania, there are almost no Shiite Bektashi in North Macedonia . There are also almost no Christians (Orthodox and Catholic) among the Albanians, which is completely different in Albania and Kosovo.

Muslims

With the incorporation of the Balkans into the Ottoman Empire, Islam also gained a foothold in what is now North Macedonia. The Ottomans built mosques, madrasas , hammams , caravanserais ( hane ) and turrets . It was a few decades if not centuries before the Albanians converted to the new religion. Macedonians (who still viewed themselves as Bulgarians during the Ottoman period) also converted to a certain extent ( Torbeschen ), but the majority retained their Christian Orthodox faith . The few unconverted Albanians quickly Bulgarized themselves. With the immigration of many Turks to Southeastern Europe as traders, diplomats or even just farmers, the area of today's Macedonia became downright multicultural. Many Albanians (especially in the cities) asserted themselves as Turks because they hoped for a higher social position and could better identify with Islam. Many families still do this today, but their number is shrinking, as Turkey plays a less important role in the country today than it did 100 years ago.

Sufists who strongly influenced Islam in Macedonia with the many Tekken also settled in many cities during the Ottoman era .

Many Muslim Albanians still celebrate individual originally Christian traditions, such as St. George's Day (Alb. Shën Gjergji ) or the name day of Demetrios of Thessaloniki (Shën Mitri) .

Orthodox

In recent years there has been an increased presence of Christian Orthodox Albanians in public life in North Macedonia, which is also known as the “national rebirth”. The politician Branko Manoillovski , who describes himself as a Christian Orthodox Albanian and is a member of the Albanian Democratic Union party for integration in the Macedonian parliament , made a significant contribution . He announced that he would use his vote in parliament to raise awareness of the Orthodox Albanians among the North Macedonian public. In an interview, the Albanian-Macedonian publicist and writer Kim Mehmeti , himself a Muslim, announced that he came from an Albanian Orthodox family.

There is no precise data on the number of Orthodox Albanians. In the Albanian media, the number of Orthodox Albanians is estimated between 75,000 and 300,000. This would increase the percentage of Albanians in the total population from 25% to up to 40%, using the data of the last census and adding the higher estimate. The proportion of Christians within the Albanian community would then be 37%.

During the celebrations for the Albanian National Day in Skopje in 2014, Branislav Sinadinovski called for the establishment of an Albanian Orthodox Church in North Macedonia. A bishop of the Macedonian Orthodox Church rejected this idea and described it as a "chauvinist political project". The Orthodox Albanian Sinadinovski is the author of the book Orthodox Albanians in the Republic of Macedonia . In April 2016 his book was presented at the Tetovo State University . Deputy Speaker of Parliament Rafiz Aliti gave a speech calling on Muslim Albanians to “respect their Orthodox Albanian brothers” and “protect them from assimilation”. The rector of the University in Tetovo, Vullnet Ameti , honored Branislav Sinadovski for "his contribution to illuminating the history of the Orthodox Albanians in Macedonia".

In August 2017, the community of Orthodox Albanians in Macedonia ( alb.Bashkësia Ortodokse e Shqiptarëve të Maqedonisë ) was founded.

Personalities (selection)

Many personalities from Albanian history come from North Macedonia. But even today there are notable Albanian writers, athletes and politicians from North Macedonia. One of the best-known was Mother Teresa (1910–1997), who was born as Anjeza Gonxhe Bojaxhiu in Skopje and who became known around the world for her humanitarian aid projects for the poor. Her family, however, does not come from North Macedonia, the father came from Albania and the mother from Kosovo. Nexhmije Hoxha , the widow of the former Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha , was born in Bitola in 1921.

Today's famous Albanians from North Macedonia include some football players such as Blerim Džemaili (* 1986 in Tetovo), Admir Mehmedi (* 1991 in Gostivar) and Berat Sadik (* 1986 in Skopje). Other personalities were or are the former State Secretary for National Defense of Turkey Hayrullah Fişek (1885–1975) and the poet Luan Starova (* 1941 in Pogradec , resident in North Macedonia). The politicians Ali Ahmeti (* 1959 in Zajas), Menduh Thaçi (* 1965 in Tetovo) and Arbën Xhaferi (1948–2012) as well as the writer Kim Mehmeti (* 1955 in Grčec) are or were well-known Albanian personalities in North Macedonia.

literature

- Thede Kahl, Izer Maksuti, Albert Ramaj: The Albanians in the Republic of Macedonia . Facts, analyzes, opinions on interethnic coexistence. In: Viennese Eastern European Studies . tape 23 . Lit Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-7000-0584-9 , ISSN 0946-7246 .

- Ilber Sela: The political question of the Albanians in Macedonia . GRIN Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-638-18713-6 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- Robert Pichler: Exploring a Landscape. Post-socialist worlds in the Macedonian-Albanian border area (Preučevanija pokrajine. Postsocialistični živiljenjski svetovi na obmejnem območju med Makedonijo in Albanijo) . Exhibition catalog. Ed .: Michael Petrowitsch (= catalog # 20 ). Pavelhaus, Laafeld (Potrna) 2012, ISBN 978-3-900181-61-1 .

Web links

Single receipts

- ↑ a b Results of the 2002 census in Macedonia. (PDF) In: State Statistics Office. Retrieved October 6, 2013 (English, PDF file; 394 kB; p. 34).

- ↑ Thede Kahl, Izer Maksuti, Albert Ramaj: The Albanians in the Republic of Macedonia . Facts, analyzes, opinions on interethnic coexistence. In: Viennese Eastern European Studies . tape 23 . Lit Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-7000-0584-9 , ISSN 0946-7246 , Separate Paths: The Demographic Behavior of Macedonians and Albanians in Macedonia 1944-2004, p. 170-171 .

- ↑ Katrin Boeckh: From the Balkan Wars to the First World War . Small State Policy and Ethnic Self-Determination in the Balkans (= Southeast European Works . Volume 97 ). Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 1996, ISBN 3-486-56173-1 , p. 42–44 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Cvetan Cvetkovski: Constitutional History of Macedonia. In: Center for European Constitutional Law. Archived from the original on March 27, 2008 ; accessed on October 6, 2013 .

- ↑ Framework Agreement. In: OSCE. Accessed March 30, 2018 (English, PDF).

- ↑ Macedonia: No tolerance for mistreatment by the police. Amnesty International , accessed October 25, 2012 .

- ^ Assembly of the Republic of Macedonia - Members of Parliament: MP's 2011–2014. In: Official website of the Macedonian Parliament. Retrieved March 30, 2018 .

- ↑ Assembly of the Republic of Macedonia - Members of Parliament: MP's 2014–2016. In: Official website of the Macedonian Parliament. Retrieved March 30, 2018 .

- ^ Assembly of the Republic of Macedonia - Members of Parliament: MP's 2016–2020. In: Official website of the Macedonian Parliament. Retrieved March 30, 2018 .

- ↑ Zhurnal. In: Official website. Retrieved October 10, 2012 (Albanian).

- ↑ Koha. In: Official website. Retrieved October 10, 2012 (Albanian).

- ↑ MRT Sat2 live. In: MRTV. Retrieved March 30, 2018 .

- ↑ Rrëfim ekskluziv, Branko Manojlovski: Nga foltorja e Parlamentit do të them se jam shqiptar (Branko Maniollovski: From the lectern in Parliament I will say that I am Albanian). In: flaka.com.mk. December 9, 2016, accessed December 27, 2017 (Albanian).

- ↑ a b Shqiptarët ortodoksë: Kthimi i vëllezërve të gjakut (Orthodox Albanians: The Return of Blood Brothers). In: Telegrafi. June 16, 2017, Retrieved December 27, 2017 (Albanian).

- ↑ Sinadinovski: Jemi 75 mijë shqiptarë ortodoks në Maqedoni (Sinadinovski: We are 75,000 Orthodox Albanians in Macedonia). In: Tetova Sot. March 19, 2017, archived from the original on December 28, 2017 ; Retrieved December 27, 2017 (Albanian).

- ↑ Peshkopi maqedonas: Krijimi i kishes ortodokse shqiptar, nje projekt shovinist (Macedonian bishop: The foundation of the Albanian Orthodox Church in Macedonia, a chauvinist project). In: Gazeta Tema. December 1, 2014, accessed December 27, 2017 (Albanian).

- ↑ Sinadinovski: Të themelohet Kishë Ortodokse për shqiptarët e Maqedonisë (Sinadinovski: An Orthodox Church should be founded for Albanians in Macedonia). In: Alsat-M. December 1, 2014, accessed December 27, 2017 (Albanian).

- ↑ Në USHT u promovua libri “Shqiptarët Ortodoksë në Republikën e Maqedonisë” (The book “Orthodox Albanians in the Republic of Macedonia” was presented at the State University of Tetovo). In: Tetovo State University. April 6, 2016, archived from the original on December 28, 2017 ; Retrieved December 27, 2017 (Albanian).

- ↑ Shpallet Bashkësia Ortodokse e Shqiptarëve të Maqedonisë. In: Lajm Press. August 24, 2017. Retrieved December 27, 2017 (Albanian).